30cm x 30cm

Patrick "Pat" O'Callaghan (28 January 1906 – 1 December 1991) was an

Irish athlete and

Olympic gold medallist. He was the first athlete from

Ireland to win an Olympic medal under the Irish flag rather than the British.

In sport he then became regarded as one of Ireland's greatest-ever athletes.

Early and private life

Pat O'Callaghan was born in the townland of Knockaneroe, near

Kanturk,

County Cork, on 28 January 1906,

the second of three sons born to Paddy O'Callaghan, a farmer, and Jane Healy. He began his education at the age of two at Derrygalun

national school. O'Callaghan progressed to

secondary school in Kanturk and at the age of fifteen he won a scholarship to the Patrician Academy in

Mallow. During his year in the Patrician Academy he cycled the 32-mile round trip from Derrygalun every day and he never missed a class. O'Callaghan subsequently studied medicine at the

Royal College of Surgeons in

Dublin. Following his graduation in 1926 he joined the

Royal Air Force Medical Service. He returned to Ireland in 1928 and set up his own medical practice in

Clonmel,

County Tipperary where he worked until his retirement in 1984.

O'Callaghan was also a renowned field sports practitioner,

greyhound trainer and storyteller.

Sporting career

Early sporting life

O’Callaghan was born into a family that had a huge interest in a variety of different sports. His uncle, Tim Vaughan, was a national sprint champion and played

Gaelic football with

Cork in 1893. O’Callaghan's eldest brother, Seán, also enjoyed football as well as winning a national 440 yards hurdles title, while his other brother,

Con, was also regarded as a gifted runner, jumper and thrower. O’Callaghan's early sporting passions included hunting, poaching and Gaelic football. He was regarded as an excellent midfielder on the

Banteer football team, while he also lined out with the

Banteer hurling team.

At university in Dublin O’Callaghan broadened his sporting experiences by joining the local senior

rugby club. This was at a time when the

Gaelic Athletic Association ‘ban’ forbade players of

Gaelic games from playing "foreign sports". It was also in Dublin that O’Callaghan first developed an interest in hammer-throwing. In 1926, he returned to his native Duhallow where he set up a training regime in hammer-throwing. Here he fashioned his own hammer by boring a one-inch hole through a 16 lb shot and filling it with the ball-bearing core of a bicycle pedal. He also set up a throwing circle in a nearby field where he trained. In 1927, O’Callaghan returned to Dublin where he won that year's hammer championship with a throw of 142’ 3”. In 1928, he retained his national title with a throw of 162’ 6”, a win which allowed him to represent the

Ireland at the forthcoming Olympic Games in

Amsterdam. On the same day, O’Callaghan's brother, Con, won the shot put and the decathlon and also qualified for the Olympic Games. Between winning his national title and competing in the Olympic Games O’Callaghan improved his throwing distance by recording a distance of 166’ 11” at the

Royal Ulster ConstabularySports in

Belfast.

1928 Olympic Games

In the summer of 1928, the three O’Callaghan brothers paid their own fares when travelling to the Olympic Games in Amsterdam. Pat O’Callaghan finished in sixth place in the preliminary round and started the final with a throw of 155’ 9”. This put him in third place behind

Ossian Skiöld of

Sweden, but ahead of

Malcolm Nokes, the favourite from

Great Britain. For his second throw, O’Callaghan used the Swede's own hammer and recorded a throw of 168’ 7”. This was 4’ more than Skoeld's throw and resulted in a first gold medal for O’Callaghan and for Ireland. The podium presentation was particularly emotional as it was the first time at an Olympic Games that the

Irish tricolour was raised and

Amhrán na bhFiann was played.

Success in Ireland

After returning from the Olympic Games, O’Callaghan cemented his reputation as a great athlete with additional successes between 1929 and 1932. In the national championships of 1930 he won the hammer, shot-putt, 56 lbs without follow, 56 lbs over-the-bar, discus and high jump.

In the summer of 1930, O’Callaghan took part in a two-day invitation event in

Stockholm where Oissian Skoeld was expected to gain revenge on the Irishman for the defeat in Amsterdam. On the first day of the competition, Skoeld broke his own European record with his very first throw. O’Callaghan followed immediately and overtook him with his own first throw and breaking the new record. On the second day of the event both O’Callaghan and Skoeld were neck-and-neck, when the former, with his last throw, set a new European record of 178’ 8” to win.

1932 Summer Olympics

By the time the

1932 Summer Olympics came around O’Callaghan was regularly throwing the hammer over 170 feet. The Irish team were much better organised on that occasion and the whole journey to

Los Angeles was funded by a church-gate collection. Shortly before departing on the 6,000-mile boat and train journey across the Atlantic O’Callaghan collected a fifth hammer title at the national championships.

On arrival in Los Angeles O’Callaghan's preparations of the defence of his title came unstuck. The surface of the hammer circle had always been of grass or clay and throwers wore field shoes with steel spikes set into the heel and sole for grip. In Los Angeles, however, a cinder surface was to be provided. The Olympic Committee of Ireland had failed to notify O’Callaghan of this change. Consequently, he came to the arena with three pairs of spiked shoes for a grass or clay surface and time did not permit a change of shoe. He wore his shortest spikes, but found that they caught in the hard gritty slab and impeded his crucial third turn. In spite of being severely impeded, he managed to qualify for the final stage of the competition with his third throw of 171’ 3”. While the final of the 400m hurdles was delayed, O’Callaghan hunted down a hacksaw and a file in the groundskeeper's shack and he cut off the spikes. O’Callaghan's second throw reached a distance of 176’ 11”, a result which allowed him to retain his Olympic title. It was Ireland's second gold medal of the day as

Bob Tisdall had earlier won a gold medal in the 400m hurdles.

Retirement

Due to the celebrations after the Olympic Games O’Callaghan didn't take part in the national athletic championships in Ireland in 1933. In spite of that he still worked hard on his training and he experimented with a fourth turn to set a new European record at 178’ 9”. By this stage O’Callaghan was rated as the top thrower in the world by the leading international sports journalists.

In the early 1930s controversy raged between the British AAA and the

National Athletic and Cycling Association of Ireland (NACAI). The British AAA claimed jurisdiction in

Northern Ireland while the NACAI claimed jurisdiction over the entire island of Ireland regardless of political division. The controversy came to a head in the lead-up to the

1936 Summer Olympics when the

IAAF finally disqualified the NACAI. O’Callaghan remained loyal to the NACAI, a decision which effectively brought an end to his international athletic career. No Irish team travelled to the 1936 Olympic Games, however O’Callaghan travelled to

Berlin as a private spectator. After Berlin, O’Callaghan's international career was over. He declined to join the new Irish Amateur Athletics Union (IAAU) or subsequent IOC recognised Amateur Athletics Union of Eire (AAUE) and continued to compete under NACAI rules. At

Fermoy in 1937 he threw 195’ 4” – more than seven feet ahead of the world record set by his old friend

Paddy 'Chicken' Ryan in 1913. This record, however, was not ratified by the AAUE or the IAAF.

In retirement O’Callaghan remained interested in athletics. He travelled to every Olympic Games up until 1988 and enjoyed fishing and poaching in Clonmel. He died on 1 December 1991.

Legacy

O'Callaghan was the

flag bearer for Ireland at the 1932 Olympics. In 1960, he became the first person to receive the Texaco Hall of Fame Award. He was made a Freeman of Clonmel in 1984, and was honorary president of Commercials Gaelic Football Club. The Dr. Pat O'Callaghan Sports Complex at Cashel Rd, Clonmel which is the home of Clonmel Town Football Club is named after him, and in January 2007 his statue was raised in Banteer, County Cork.

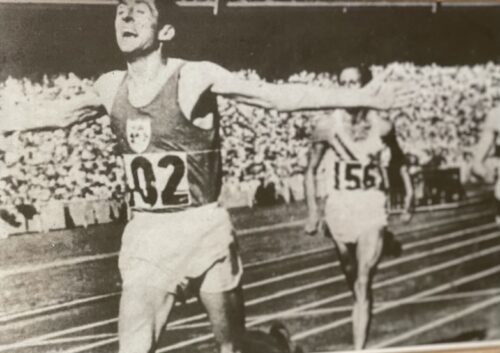

20cm x 35cm Limerick Ronald Michael Delany (born 6 March 1935), better known as Ron or Ronnie Delany, is an Irish former athlete, who specialised in middle-distance running. He won a gold medal in the 1500 metres event at the 1956 Summer Olympicsin Melbourne. He later earned a bronze medal in the 1500 metres event at the 1958 European Athletics Championships in Stockholm. Delany also competed at the 1954 European Athletics Championships in Bern and the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, though was less successful on these occasions. Retiring from competitive athletics in 1962, he has secured his status as Ireland's most recognisable Olympian as well as one of the greatest sportsmen and international ambassadors in his country's history.

20cm x 35cm Limerick Ronald Michael Delany (born 6 March 1935), better known as Ron or Ronnie Delany, is an Irish former athlete, who specialised in middle-distance running. He won a gold medal in the 1500 metres event at the 1956 Summer Olympicsin Melbourne. He later earned a bronze medal in the 1500 metres event at the 1958 European Athletics Championships in Stockholm. Delany also competed at the 1954 European Athletics Championships in Bern and the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, though was less successful on these occasions. Retiring from competitive athletics in 1962, he has secured his status as Ireland's most recognisable Olympian as well as one of the greatest sportsmen and international ambassadors in his country's history.

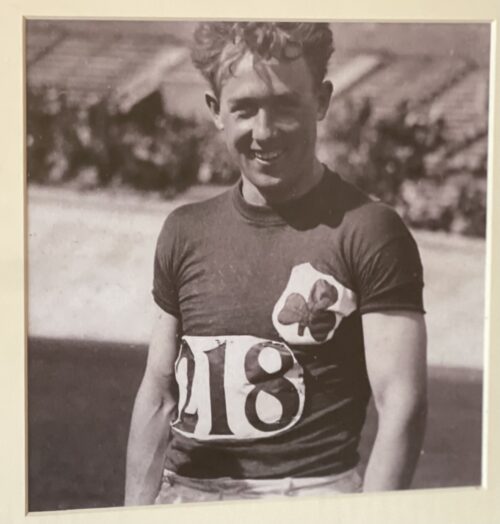

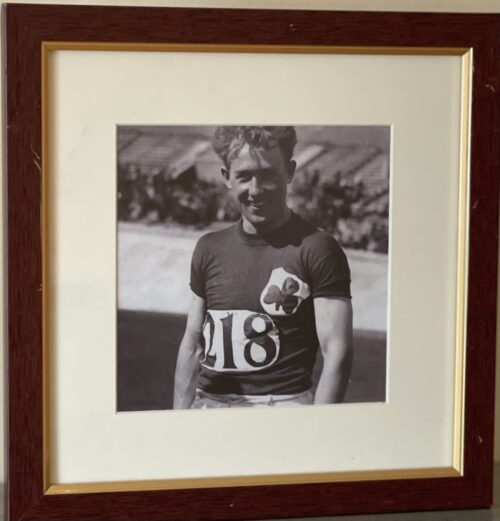

30cm x 30cm Patrick "Pat" O'Callaghan (28 January 1906 – 1 December 1991) was an Irish athlete and Olympic gold medallist. He was the first athlete from Ireland to win an Olympic medal under the Irish flag rather than the British. In sport he then became regarded as one of Ireland's greatest-ever athletes.

30cm x 30cm Patrick "Pat" O'Callaghan (28 January 1906 – 1 December 1991) was an Irish athlete and Olympic gold medallist. He was the first athlete from Ireland to win an Olympic medal under the Irish flag rather than the British. In sport he then became regarded as one of Ireland's greatest-ever athletes.