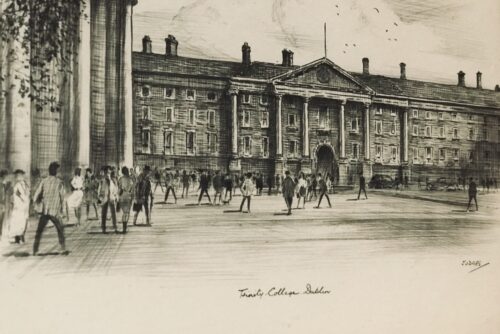

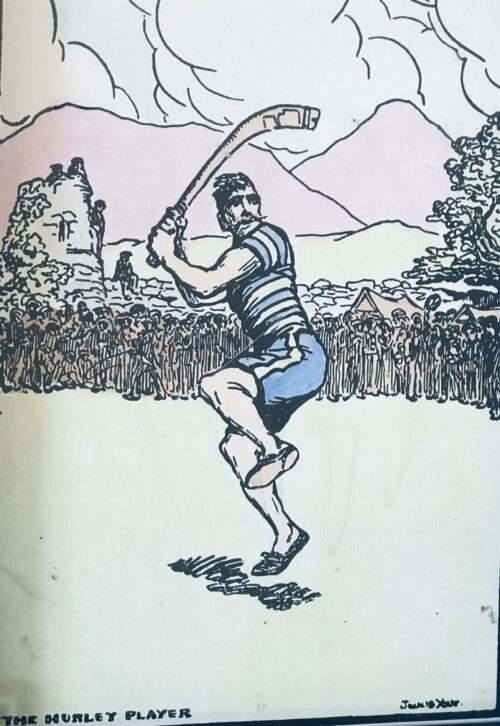

The Hurley Playerby Jack B Yeats in nice, offset frame.

33cm x 24cm

Jack Butler Yeats RHA (29 August 1871 – 28 March 1957) was an

Irish artist and Olympic medalist.

W. B. Yeats was his brother.

Butler's early style was that of an illustrator; he only began to work regularly in

oils in 1906.

His early pictures are simple lyrical depictions of

landscapes and figures, predominantly from the west of Ireland—especially of his boyhood home of

Sligo. Yeats's work contains elements of

Romanticism. He later would adopt the style of

Expressionism

Biography

Yeats was born in

London, England. He was the youngest son of Irish portraitist

John Butler Yeats and the brother of

W. B. Yeats, who received the 1923

Nobel Prize in Literature. He grew up in

Sligo with his maternal grandparents, before returning to his parents' home in London in 1887. Early in his career he worked as an illustrator for magazines like the

Boy's Own Paper and

Judy, drew comic strips, including the

Sherlock Holmes parody "Chubb-Lock Homes" for

Comic Cuts, and wrote articles for

Punch under the pseudonym "W. Bird".

In 1894 he married Mary Cottenham, also a native of England and two years his senior, and resided in Wicklow according to the

Census of Ireland, 1911.

From around 1920, he developed into an intensely

Expressionist artist, moving from illustration to

Symbolism. He was sympathetic to the

Irish Republican cause, but not politically active. However, he believed that 'a painter must be part of the land and of the life he paints', and his own artistic development, as a

Modernist and

Expressionist, helped articulate a modern

Dublin of the 20th century, partly by depicting specifically Irish subjects, but also by doing so in the light of universal themes such as the loneliness of the individual, and the universality of the plight of man.

Samuel Beckett wrote that "Yeats is with the great of our time... because he brings light, as only the great dare to bring light, to the issueless predicament of existence."

The Marxist art critic and author

John Berger also paid tribute to Yeats from a very different perspective, praising the artist as a "great painter" with a "sense of the future, an awareness of the possibility of a world other than the one we know".

His favourite subjects included the Irish landscape, horses, circus and travelling players. His early paintings and drawings are distinguished by an energetic simplicity of line and colour, his later paintings by an extremely vigorous and experimental treatment of often thickly applied paint. He frequently abandoned the brush altogether, applying paint in a variety of different ways, and was deeply interested in the expressive power of colour. Despite his position as the most important Irish artist of the 20th century (

and the first to sell for over £1m), he took no pupils and allowed no one to watch him work, so he remains a unique figure. The artist closest to him in style is his friend, the Austrian painter,

Oskar Kokoschka.

Besides painting, Yeats had a significant interest in

theatre and in

literature. He was a close friend of

Samuel Beckett. He designed sets for the

Abbey Theatre, and three of his own plays were also produced there. He wrote novels in a

stream of consciousness style that

Joyce acknowledged, and also many essays. His literary works include

The Careless Flower,

The Amaranthers (much admired by Beckett),

Ah Well, A Romance in Perpetuity,

And To You Also, and

The Charmed Life. Yeats's paintings usually bear poetic and evocative titles. Indeed, his father recognized that Jack was a far better painter than he, and also believed that 'some day I will be remembered as the father of a great poet, and the poet is Jack'.He was elected a member of the

Royal Hibernian Academy in 1916.

He died in Dublin in 1957, and was buried in

Mount Jerome Cemetery.

Yeats holds the distinction of being Ireland's first medalist at the

Olympic Games in the wake of creation of the

Irish Free State. At the

1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, Yeats' painting

The Liffey Swim won a silver medal in the

arts and culture segment of the Games. In the competition records the painting is simply entitled

Swimming.

Works

In November 2010, one of Yeats's works,

A Horseman Enters a Town at Night, painted in 1948 and previously owned by novelist

Graham Greene, sold for nearly £350,000 at a

Christie's auction in London. A smaller work,

Man in a Room Thinking, painted in 1947, sold for £66,000 at the same auction. In 1999 the painting,

The Wild Ones, had sold at

Sotheby's in London for over £1.2m, the highest price yet paid for a Yeats painting.

Adam's Auctioneers hold the Irish record sale price for a Yeats painting,

A Fair Day, Mayo (1925), which sold for €1,000,000 in September 2011.

Hosting museums

- The Hunt Museum, Limerick

- The National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

- The Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin

- Crawford Art Gallery, Cork

- Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin

- The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

- Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

- Model Arts and Niland Gallery, Sligo

- The Municipal Art Collection, Waterford

- Ulster Museum, Belfast

- The Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame

The Geography of Hurling

‘The Hurley Player’ by Jack B. Yeats

Kevin Whelan

Why is hurling currently popular in a compact region centred on east Munster and south Leinster, and in isolated pockets in the Glens of Antrim and in the Ards peninsula of County Down? The answer lies in an exploration of the interplay between culture, politics and environment over a long period of time.

TWO VERSIONS

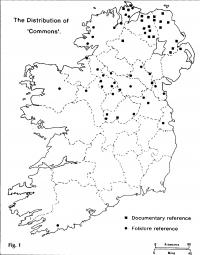

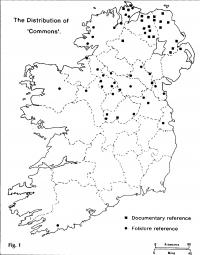

By the eighteenth century it is quite clear that there were two principal, and regionally distinct,versions of the game. One was akin to modern field hockey, or shinty, in that it did not allow handling of the ball; it was played with a narrow, crooked stick; it used a hard wooden ball (the ‘crag’); it was mainly a winter game. This game, called camán (anglicised to ‘commons’), was confined to the northern half of the country; its southern limits were set sharply where the small farms of the drumlin belt petered out into the pastoral central lowlands. (Fig 1)

The second version of the game (iomán or báire) was of southern provenance. The ball could be handled or carried on the hurl, which was flat and round-headed; the ball (the sliothar) was soft and made of animal hair; the game was played in summer. Unlike commons, this form of hurling was patronised by the gentry, as a spectator and gambling sport, associated with fairs and other public gatherings, and involved a much greater degree of organisation (including advertising) than the more demotic ‘commons’. A 1742 advertisement for Ballyspellan Spa in Kilkenny noted that ‘horse racing, dancing and hurling will be provided for the pleasure of the quality at the spa’.

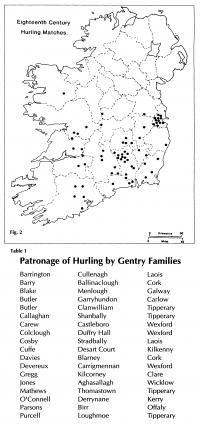

LANDLORD PATRONAGE

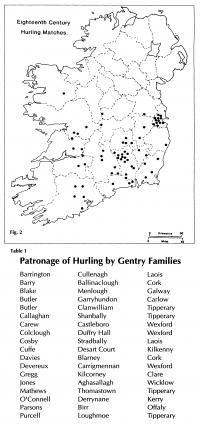

A number of factors determined the distribution of the southern game. (Fig. 2) The most important was the patronage of local gentry families, particularly those most closely embedded in the life of the local people. (Table 1) They picked the teams, arranged the hurling greens and supervised the matches, which were frequently organised as gambling events. The southern hurling zone coincides with the area where, in the late medieval period, the Norman and Gaelic worlds fused to produce a vigorous culture, reflected, for example, in the towerhouse as an architectural innovation. It coincides with well-drained, level terrain, seldom moving too far off the dry sod of limestone areas, which also happen to produce the best material for hurls – ash. It is closely linked to the distribution of big farms, where the relatively comfortable lifestyle afforded the leisure to pursue the sport.

Landlord patronage was essential to the well-being of the southern game; once it was removed, the structures it supported crumbled and the game collapsed into shapeless anarchy. The progressive separation of the manners and language of the élite from the common people was a pan-European phenomenon in the modern period. The gentry’s disengagement from immersion in the shared intimacies of daily life can be seen not just in hurling, but in other areas of language, music, sport and behaviour, as the gradual reception of metropolitan ideas eroded the older loyalties. As one hostile observer put it:

A hurling match is a scene of drunkenness, blasphemy and all kinds and manner of debauchery and faith, for my part, I would liken it to nothing else but to the idea I form of the Stygian regions where the daemonic inhabitants delight in torturing and afflicting each other.

DECLINE

By the mid nineteenth century, hurling had declined so steeply that it survived only in three pockets, around Cork city, in south-east Galway and in the area north of Wexford town. Amongst the reasons for decline were the withdrawal of gentry patronage in an age of political turbulence, sabbitudinarianism, modernisation and the dislocating impact of the Famine. Landlord, priest and magistrate all turned against the game. The older ‘moral economy’, which had linked landlord and tenant in bonds of patronage and deference, gave way to a sharper, adversarial relationship, especially in the 1790s, as the impact of the French Revolution in Ireland created a greater class-consciousness. Politicisation led to a growing anti-landlord feeling, which had been far more subdued in the heyday of gentry-sponsored hurling between the 1740s and 1760s.

MICHAEL CUSACK & THE GAA

MICHAEL CUSACK & THE GAA

The model of élite participation in popular culture is a threefold process: first immersion, then withdrawal, and, finally rediscovery, invariably by an educated élite, and often with a nationalist agenda. ‘Rediscovery’ usually involves an invention of tradition, creating a packaged, homogenised and often false version of an idealised popular culture – as, for example, in the cult of the Highland kilt. The relationship of hurling and the newly established Gaelic Athletic Association in the 1880s shows this third phase with textbook clarity. Thus, when Michael Cusack set about reviving the game, he codified a synthetic version, principally modelled on the southern ‘iomán’ version that he had known as a child in Clare. Not surprisingly, this new game never caught on in the old ‘commons’ area, with the Glens of Antrim being the only major exception. Cusack and his GAA backers also wished to use the game as a nationalising idiom, a symbolic language of identity filling the void created by the speed of anglicisation. It had therefore to be sharply fenced off in organisational terms from competing ‘anglicised’ sports like cricket, soccer and rugby. Thus, from the beginning, the revived game had a nationalist veneer, its rules of association bristling like a porcupine with protective nationalist quills on which its perceived opponents would have to impale themselves. Its principal backers were those already active in the nationalist political culture of the time, classically the I.R.B. Its spread depended on the active support of an increasingly nationalist Catholic middle class – and as in every country concerned with the invention of tradition, its social constituency included especially journalists, publicans, schoolteachers, clerks, artisans and clerics. Thus, hurling’s early success was in south Leinster and east Munster, the very region which pioneered popular Irish nationalist politics – from the O’Connell campaign, to the devotional revolution in Irish Catholicism, from Fr. Matthews’ temperance campaign, to the Fenians, to the take-over of local government. The GAA was a classic example of the radical conservatism of this region – conservative in its ethos and ideology, radical in its techniques of organisation and mobilisation. The spread of hurling can be very closely matched to the spread of other radical conservative movements of this period – the diffusion of the indigenous Catholic teaching orders and the spread of co-operative dairying.

It would, however, be a mistake to see the spread of hurling under the aegis of the GAA solely in nationalist terms. The codification and success of gaelic games should be compared to the almost contemporaneous success in Britain of codified versions of soccer and rugby. All these were linked to rising spending power, a shortened working week (and the associated development of the ‘weekend’), improved and cheaper mass transport facilities which made spectator sports viable, expanded leisure time, the desire for organised sport among the working classes, and the commercialisation of leisure itself. The really distinctive feature of the GAA’s success was that it occurred in what was still a predominantly agrarian society. That success rested on the shrewd application of the principle of territoriality.

TERRITORIAL ALLEGIANCE

Irish rural life was essentially local life. Hurling was quintessentially a territorially based game – teams based on communities, parishes, counties, pitted one against the other. The painter Tony O’Malley has contrasted this tribal-territorial element in Irish sport to English attitudes:

If neighbours were playing like New Ross and Tullogher, there would be a real needle in it. When Carrickshock were playing, I once heard an old man shouting ‘come on the men that bate the tithe proctors’ and there was a tremor and real fervour in his voice. It was a battle cry, with hurleys as the swords, but with the same intensity.

Similar forces of territoriality have been identified behind the success of cricket in the West Indies and rugby in the Welsh valleys. The GAA tapped this deep-seated territorial loyalty, of the type which is beautifully captured in the rhetorical climax of the great underground classic of rural Ireland, Knocknagow or the Homes of Tipperary by Charles J. Kickham. Matt Donovan (Matt the Thrasher), the village hero, is competing against the outsider Captain French in a sledge-throwing contest. In the absence of steroids, Matt is pumping himself up before his throw:

Someone struck the big drum a single blow, as if by accident and, turning round quickly, the thatched roofs of the hamlet caught his eye. And, strange to say, those old mud walls and thatched roofs roused him as nothing else could. His breast heaved, as with glistening eyes, and that soft plaintive smile of his, he uttered the words, ‘For the credit of the little village!’ in a tone of the deepest tenderness. Then, grasping the sledge in his right hand, and drawing himself up to his full height, he measured the captain’s cast with his eye. The muscles of his arms seemed to start out like cords of steel as he wheeled slowly round and shot the ponderous hammer through the air. His eyes dilated as, with quivering nostrils, he watched its flight, till it fell so far beyond the best mark that even he himself started with astonishment. Then a shout of exultation burst from the excited throng; hands were convulsively grasped, and hats sent flying in the air; and in their wild joy they crushed around him and tried to lift him upon their shoulders.

The territorial allegiance and communal spirit celebrated and idealised by Kickham have died hard in Ireland. GAA club colours, for example were often drawn from old faction favours and, even now, an occasional faction slogan can still be heard. ‘If any man can, an Alley man can’. ‘Squeeze ‘em up Moycarkey and hang ‘em out to dry!’ Lingering animosities can sometimes surface in surprising ways: it is not unknown, for example, for an irate and disappointed Wexford hurling supporter (and what other kind of Wexford supporter is there?) to hurl abuse at Kilkenny, recalling an incident that occurred in Castlecomer to indignant Wexford United Irishmen: ‘Sure what good are they anyway? Didn’t they piss on the powder in ‘98?’ A possibly apocryphal incident occurred after a fiercely contested Cork-Tipperary match. Cork won but in Tipperary eyes that was solely due to a biased Limerick referee. When the disgruntled Tipperary supporters poured off the train at Thurles, they vented their frustrations on the only Limerick man they could find in the town – by tarring and feathering the statue of Archbishop Croke in the Square (presumably the only time in Irish history that a Catholic bishop has been tarred and feathered).

With the notable exception of Cork, the game has not been successfully transplanted into the cities. In Cork, close-knit working-class neighbourhoods like Blackrock and Gouldings Glen (home of Glen Rovers), and the strong antagonism between the hilly northside and the flat southside of the city, nourished the territoriality and community spirit so important to the game’s health. In Dublin, however, the modern suburbs, based on diversity, newness and mobility, have not proved hospitable receptacles of the game. Brendan Behan, brought up in the shadow of Croke Park, commented:

At home we played soccer in the street and sometimes a version of hurling, fast and sometimes savage, adapted from the long-pucking grace of Kilkenny and Tipperary to the crookeder, foreshortened, snappier brutality of the confines of a slum thoroughfare.

THE PRESENT HURLING REGION

THE PRESENT HURLING REGION

If one looks at the present hurling core region, it is remarkably compact. It also exhibits striking continuity with the earlier ‘iomán’ region. (Fig. 3) The hurling heartland is focused on the three counties of Cork, Tipperary and Kilkenny, with a supporting cast of adjacent counties – Limerick, Clare, Galway, Offaly, Laois, Waterford and Wexford. In the hurling core, the game is king, and very closely stitched into the fabric of the community. Describing the situation in Rathnure, Billy Rackard claimed that in the absence of hurling, ‘the parish would commit suicide, if a parish could commit suicide!’ The boundaries of the hurling region are surprisingly well-defined. To the north, the midland bogs act, as in a way they have done throughout history, as a buffer zone, resolutely impervious to the spread of cultural influences from further south. The western edge of the hurling zone can be traced over a long distance. In County Galway, for example, its boundaries run along a line from Ballinasloe to the city; north of this line is the Tuam-Dunmore area, and west of it is Connemara, both footballing territories. In County Clare, the boundary runs from Tubber on the Galway border through Corofin and Kilmaley to Labasheeda on the Shannon estuary. Last summer, the tremendous achievement of Clare in winning a Munster football championship was most thoroughly relished in the footballing bastion of west Clare, from Kilkee and Doonbeg to Milltown Malbay. One could easily establish this pattern by looking at the thickening density of the forest of flags as one drove from east to west in August.

Across the Shannon in Limerick, the football-hurling divide runs clearly along the scarp dividing hilly west Limerick from the lush limestone lowlands of east Limerick. West of this is an enclave of hurling parishes in the footballing

‘The Hurley Player’ by Jack B. Yeats

kingdom of Kerry in the area north of Tralee, in Ardfert, Bally heigue, Causeway and Ballyduff. From Limerick, the hurling boundary loops through County Cork from Mallow to the city and then to the coast at Cloyne – home to the maestro Christy Ring, who famously expressed his strategy for promoting the game in Cork – by stabbing a knife through every football found east of that line. Outside this core region, there are only the hurling enclaves in the Glens of Antrim and on the tip of the Ards peninsula, where the clubs of Ballycran, Ballygalget and Portaferry backbone Down’s hurling revival.

The interesting question then is how these boundaries formed. In almost every case, that boundary divides big farm and small farm areas and marks the transition from fertile, drift-covered limestone lowland to hillier, hungrier, wetter shales, flagstones, grits and granites. In County Galway, for example, hurling has not put down roots in the bony granite outcrops of Connemara, and in Clare the poorly drained flagstone deposits are equally inhospitable. If ash is emblematic of hurling areas, the rush is the distinctive symbol of football territory.

CONCLUSION

This brief case study illustrates the interplay of what the French call la longue durée – the long evolution of history – and les évenements – the specific, precise incidents and personalities which intervene and alter that evolution. Hurling offers a classic Irish example, and the current game demonstrates that, beneath the superficial breaks, fractures and discontinuities, there are sometimes surprisingly stable, deep structures. If the idiom of the game has changed, its grammar stays the same.

.jpg)