|

|

|

|

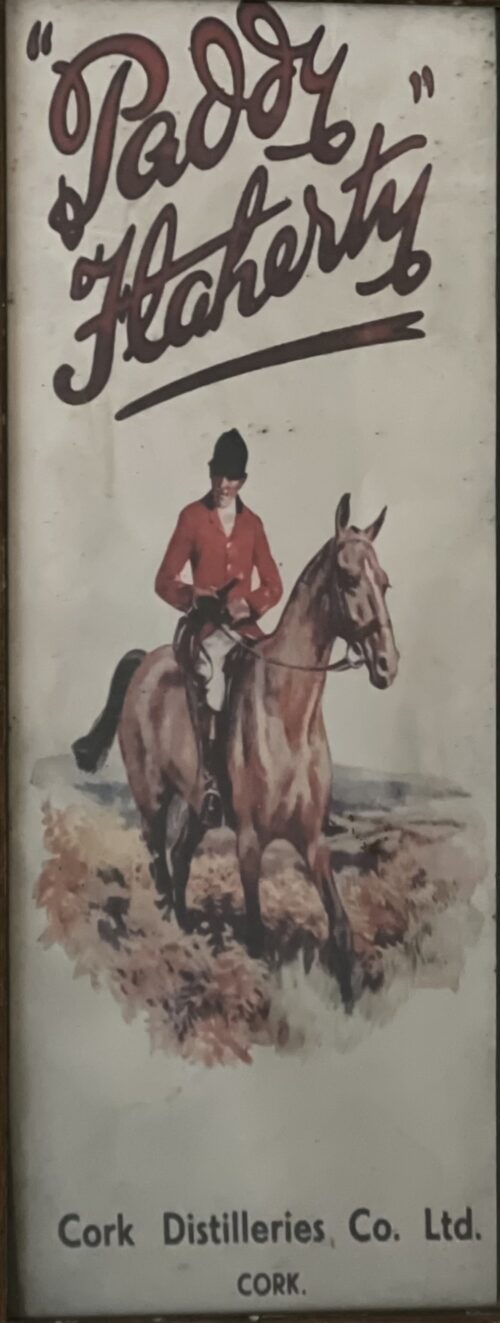

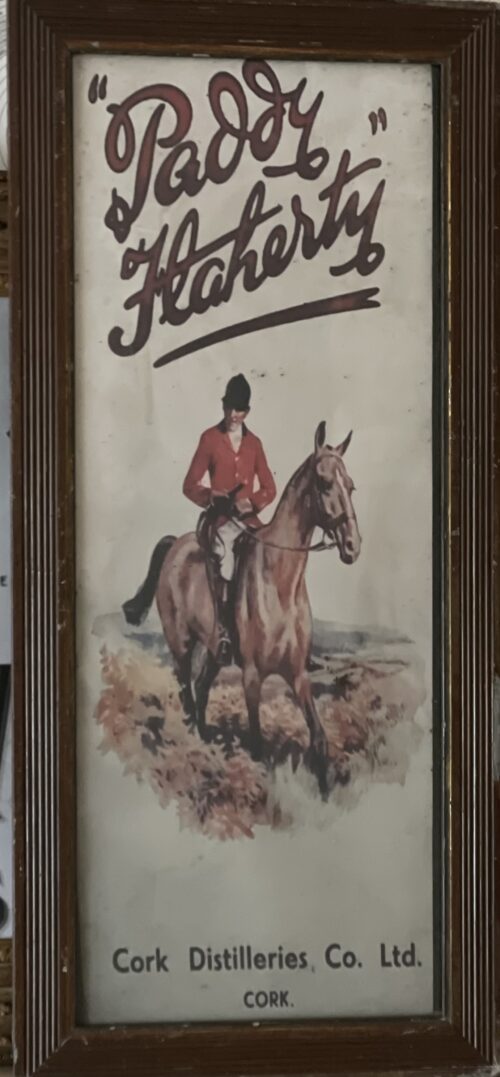

| Introduced | 1879, renamed as Paddy in 1912 |

|---|---|

-

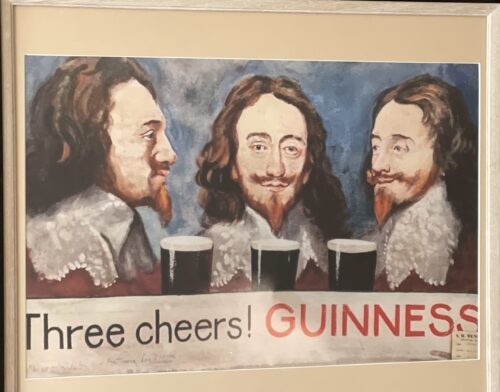

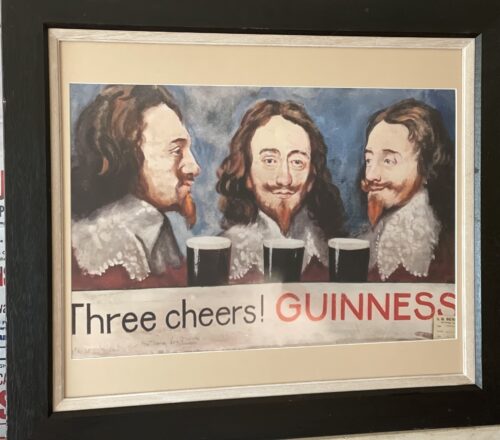

60cm x 38cm Limerick

60cm x 38cm Limerick

Paddy is a brand of blended Irish whiskey produced by Irish Distillers, at the Midleton distillery in County Cork, on behalf of Sazerac, a privately held American company. Irish distillers owned the brand until its sale to Sazerac in 2016. As of 2016, Paddy is the fourth largest selling Irish whiskey in the WorldHistory The Cork Distilleries Company was founded in 1867 to merge four existing distilleries in Cork city (the North Mall, the Green, Watercourse Road, and Daly's) under the control of one group.A fifth distillery, the Midleton distillery, joined the group soon after in 1868. In 1882, the company hired a young Corkman called Paddy Flaherty as a salesman. Flaherty travelled the pubs of Cork marketing the company's unwieldy named "Cork Distilleries Company Old Irish Whiskey".His sales techniques (which including free rounds of drinks for customers) were so good, that when publicans ran low on stock they would write the distillery to reorder cases of "Paddy Flaherty's whiskey". In 1912, with his name having become synonymous with the whiskey, the distillery officially renamed the whiskey Paddy Irish Whiskey in his honour. In 1920s and 1930s in Ireland, whiskey was sold in casks from the distillery to wholesalers, who would in turn sell it on to publicans.To prevent fluctuations in quality due to middlemen diluting their casks, Cork Distilleries Company decided to bottle their own whiskey known as Paddy, becoming one of the first to do so. In 1988, following an unsolicited takeover offer by Grand Metropolitan, Irish Distillers approached Pernod Ricard and subsequently became a subsidiary of the French drinks conglomerate, following a friendly takeover bid. In 2016, Pernod Ricard sold the Paddy brand to Sazerac, a privately held American firm for an undisclosed fee. Pernod Ricard stated that the sale was in order "simplify" their portfolio, and allow for more targeted investment in their other Irish whiskey brands, such as Jameson and Powers. At the time of the sale, Paddy was the fourth largest selling Irish whiskey brand in the world, with sales of 200,000 9-litre cases per annum, across 28 countries worldwide. Paddy whiskey is distilled three times and matured in oak casks for up to seven years.Compared with other Irish whiskeys, Paddy has a comparatively low pot still content and a high malt content in its blend. Jim Murray, author of the Whiskey bible, has rated Paddy as "one of the softest of all Ireland's whiskeys". -

65cm x 45cm Limerick

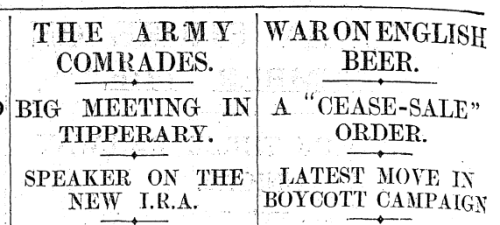

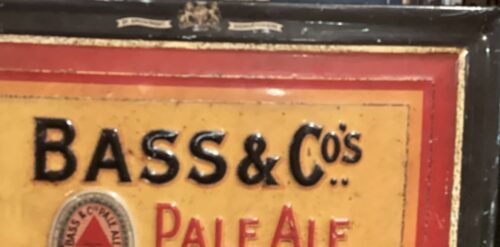

65cm x 45cm LimerickBass,the former beer of choice of An Taoiseach Bertie Ahern,the Bass Ireland Brewery operated on the Glen Road in West Belfast for 107 years until its closure in 2004.But despite its popularity, this ale would be the cause of bitter controversy in the 1930s as you can learn below.

Founded in 1777 by William Bass in Burton-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, England.The main brand was Bass Pale Ale, once the highest-selling beer in the UK.By 1877, Bass had become the largest brewery in the world, with an annual output of one million barrels.Its pale ale was exported throughout the British Empire, and the company's distinctive red triangle became the UK's first registered trade mark. In the early 1930s republicans in Dublin and elsewhere waged a campaign of intimidation against publicans who sold Bass ale, which involved violent tactics and grabbed headlines at home and further afield. This campaign occurred within a broader movement calling for the boycott of British goods in Ireland, spearheaded by the IRA. Bass was not alone a British product, but republicans took issue with Colonel John Gretton, who was chairman of the company and a Conservative politician in his day.In Britain,Ireland and the Second World War, Ian Woods notes that the republican newspaper An Phoblacht set the republican boycott of Bass in a broader context , noting that there should be “No British ales. No British sweets or chocolate. Shoulder to shoulder for a nationwide boycott of British goods. Fling back the challenge of the robber empire.”

In late 1932, Irish newspapers began to report on a sustained campaign against Bass ale, which was not strictly confined to Dublin. On December 5th 1932, The Irish Times asked:

Will there be free beer in the Irish Free State at the end of this week? The question is prompted by the orders that are said to have been given to publicans in Dublin towards the end of last week not to sell Bass after a specified date.

The paper went on to claim that men visited Dublin pubs and told publicans “to remove display cards advertising Bass, to dispose of their stock within a week, and not to order any more of this ale, explaining that their instructions were given in furtherance of the campaign to boycott British goods.” The paper proclaimed a ‘War on English Beer’ in its headline. The same routine, of men visiting and threatening public houses, was reported to have happened in Cork.

It was later reported that on November 25th young men had broken into the stores owned by Bass at Moore Lane and attempted to do damage to Bass property. When put before the courts, it was reported that the republicans claimed that “Colonel Gretton, the chairman of the company, was a bitter enemy of the Irish people” and that he “availed himself of every opportunity to vent his hate, and was an ardent supporter of the campaign of murder and pillage pursued by the Black and Tans.” Remarkably, there were cheers in court as the men were found not guilty, and it was noted that they had no intention of stealing from Bass, and the damage done to the premises amounted to less than £5.

A campaign of intimidation carried into January 1933, when pubs who were not following the boycott had their signs tarred, and several glass signs advertising the ale were smashed across the city. ‘BOYCOTT BRITISH GOODS’ was painted across several Bass advertisements in the city.

Throughout 1933, there were numerous examples of republicans entering pubs and smashing the supply of Bass bottles behind the counter. This activity was not confined to Dublin,as this report from late August shows. It was noted that the men publicly stated that they belonged to the IRA.

September appears to have been a particularly active period in the boycott, with Brian Hanley identifying Dublin, Tralee, Naas, Drogheda and Waterford among the places were publicans were targetted in his study The IRA: 1926-1936. One of the most interesting incidents occurring in Dun Laoghaire. There, newspapers reported that on September 4th 1933 “more than fifty young men marched through the streets” before raiding the premises of Michael Moynihan, a local publican. Bottles of Bass were flung onto the roadway and advertisements destroyed. Five young men were apprehended for their role in the disturbances, and a series of court cases nationwide would insure that the Bass boycott was one of the big stories of September 1933.

The young men arrested in Dun Laoghaire refused to give their name or any information to the police, and on September 8th events at the Dublin District Court led to police baton charging crowds. The Irish Times reported that about fifty supporters of the young men gathered outside the court with placards such as ‘Irish Goods for Irish People’, and inside the court a cry of ‘Up The Republic!’ led to the judge slamming the young men, who told him they did not recognise his court. The night before had seen some anti-Bass activity in the city, with the smashing of Bass signs at Burgh Quay. This came after attacks on pubs at Lincoln Place and Chancery Street. It wasn’t long before Mountjoy and other prisons began to home some of those involved in the Boycott Bass campaign, which the state was by now eager to suppress.

An undated image of a demonstration to boycott British goods. Credit: http://irishmemory.blogspot.ie/

This dramatic court appearance was followed by similar scenes in Kilmainham, where twelve men were brought before the courts for a raid on the Dead Man’s Pub, near to Palmerstown in West Dublin. Almost all in their 20s, these men mostly gave addresses in Clondalkin. Their court case was interesting as charges of kidnapping were put forward, as Michael Murray claimed the men had driven him to the Featherbed mountain. By this stage, other Bass prisoners had begun a hungerstrike, and while a lack of evidence allowed the men to go free, heavy fines were handed out to an individual who the judge was certain had been involved.

The decision to go on hungerstrike brought considerable attention on prisoners in Mountjoy, and Maud Gonne MacBride spoke to the media on their behalf, telling the Irish Press on September 18th that political treatment was sought by the men. This strike had begun over a week previously on the 10th, and by the 18th it was understood that nine young men were involved. Yet by late September, it was evident the campaign was slowing down, particularly in Dublin.

The controversy around the boycott Bass campaign featured in Dáil debates on several occasions. In late September Eamonn O’Neill T.D noted that he believed such attacks were being allowed to be carried out “with a certain sort of connivance from the Government opposite”, saying:

I suppose the Minister is aware that this campaign against Bass, the destruction of full bottles of Bass, the destruction of Bass signs and the disfigurement of premises which Messrs. Bass hold has been proclaimed by certain bodies to be a national campaign in furtherance of the “Boycott British Goods” policy. I put it to the Minister that the compensation charges in respect of such claims should be made a national charge as it is proclaimed to be a national campaign and should not be placed on the overburdened taxpayers in the towns in which these terrible outrages are allowed to take place with a certain sort of connivance from the Government opposite.

Another contribution in the Dáil worth quoting came from Daniel Morrissey T.D, perhaps a Smithwicks man, who felt it necessary to say that we were producing “an ale that can compare favourably with any ale produced elsewhere” while condemning the actions of those targeting publicans:

I want to say that so far as I am concerned I have no brief good, bad, or indifferent, for Bass’s ale. We are producing in this country at the moment—and I am stating this quite frankly as one who has a little experience of it—an ale that can compare favourably with any ale produced elsewhere. But let us be quite clear that if we are going to have tariffs or embargoes, no tariffs or embargoes can be issued or given effect to in this country by any person, any group of persons, or any organisation other than the Government elected by the people of the country.

Tim Pat Coogan claims in his history of the IRA that this boycott brought the republican movement into conflict with the Army Comrades Association, later popularly known as the ‘Blueshirts’. He claims that following attacks in Dublin in December 1932, “the Dublin vitners appealed to the ACA for protection and shipments of Bass were guarded by bodyguards of ACA without further incident.” Yet it is undeniable there were many incidents of intimidation against suppliers and deliverers of the product into 1933.

Not all republicans believed the ‘Boycott Bass’ campaign had been worthwhile. Patrick Byrne, who would later become secretary within the Republican Congress group, later wrote that this was a time when there were seemingly bigger issues, like mass unemployment and labour disputes in Belfast, yet:

In this situation, while the revolution was being served up on a plate in Belfast, what was the IRA leadership doing? Organising a ‘Boycott Bass’ Campaign. Because of some disparaging remarks the Bass boss, Colonel Gretton, was reported to have made about the Irish, some IRA leaders took umbrage and sent units out onto the streets of Dublin and elsewhere to raid pubs, terrify the customers, and destroy perfectly good stocks of bottled Bass, an activity in which I regret to say I was engaged.

Historian Brian Hanley has noted by late 1933 “there was little effort to boycott anything except Bass and the desperation of the IRA in hoping violence would revive the campaign was in fact an admission of its failure. At the 1934 convention the campaign was quietly abandoned.”

Interestingly, this wasn’t the last time republicans would threaten Bass. In 1986 The Irish Times reported that Bass and Guinness were both threatened on the basis that they were supplying to British Army bases and RUC stations, on the basis of providing a service to security forces.

-

72cm x 46cm The original J. H. Ireland Grill Room opened in Chicago in 1906, and was one of the windy city's best loved restaurants. Proprietor Jim Ireland expanded the property over two decades, adding a Lobster Grotto, a Marine Room and a banqueting hall modeled after the saloon of a passenger ship. The infamous gangster John Dillinger often dined at J. H. Ireland - he liked the frog legs - and famed attorney Clarence Darrow ate a victory dinner at the restaurant at the end of the famous Leopold and Loeb murder trial. This 1940s menu cover by folk artist Charles Jerred, in wonderfully vibrant shades of green and red, showcases what was one of Chicago's best loved restaurants and is a Love Menu Art best seller.

72cm x 46cm The original J. H. Ireland Grill Room opened in Chicago in 1906, and was one of the windy city's best loved restaurants. Proprietor Jim Ireland expanded the property over two decades, adding a Lobster Grotto, a Marine Room and a banqueting hall modeled after the saloon of a passenger ship. The infamous gangster John Dillinger often dined at J. H. Ireland - he liked the frog legs - and famed attorney Clarence Darrow ate a victory dinner at the restaurant at the end of the famous Leopold and Loeb murder trial. This 1940s menu cover by folk artist Charles Jerred, in wonderfully vibrant shades of green and red, showcases what was one of Chicago's best loved restaurants and is a Love Menu Art best seller. -

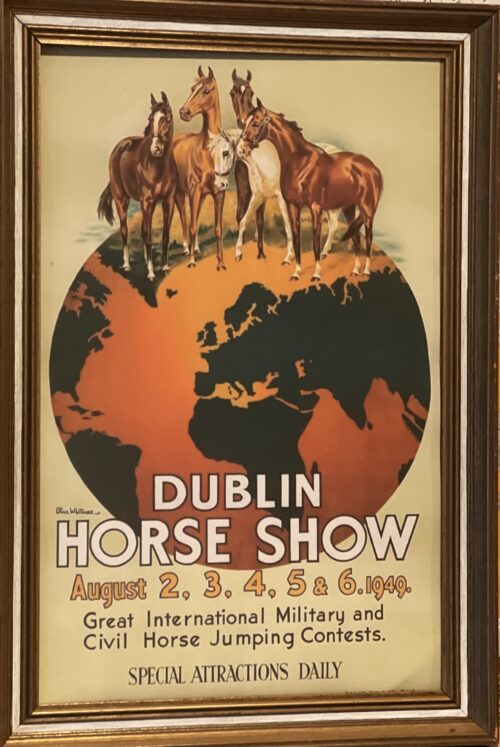

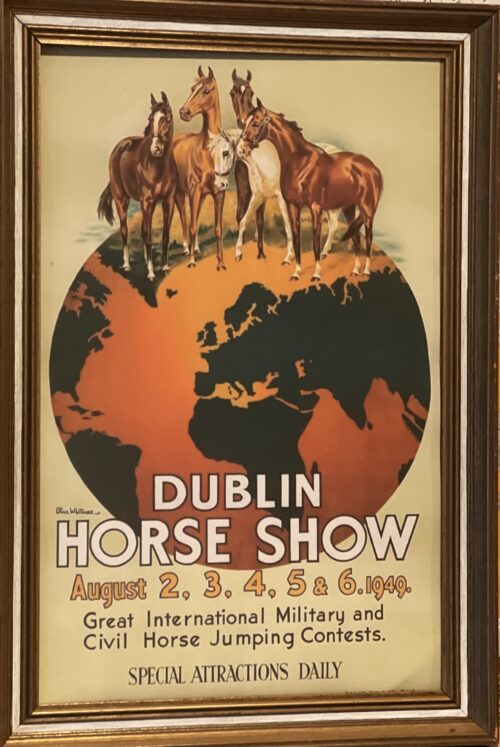

68cm x 45cm Naas Co Kildare The first Dublin Horse Show took place in 1864 and was operated in conjunction with the Royal Agricultural Society of Ireland. The first solely Society-run Horse Show was held in 1868 and was one of the earliest "leaping" competitions ever held.Over time it has become a high-profile International show jumping competition, national showing competition and major entertainment event in Ireland. In 1982 the RDS hosted the Show Jumping World Championshipsand incorporated it into the Dublin Horse Show of that year. The Dublin Horse Show has an array of national & international show jumping competitions and world class equestrian entertainment, great shopping, delicious food, music & fantastic daily entertainment. There are over 130 classes at the Show and they can be generally categorised into the following types of equestrian competitions: showing classes, performance classes and showjumping classes.

68cm x 45cm Naas Co Kildare The first Dublin Horse Show took place in 1864 and was operated in conjunction with the Royal Agricultural Society of Ireland. The first solely Society-run Horse Show was held in 1868 and was one of the earliest "leaping" competitions ever held.Over time it has become a high-profile International show jumping competition, national showing competition and major entertainment event in Ireland. In 1982 the RDS hosted the Show Jumping World Championshipsand incorporated it into the Dublin Horse Show of that year. The Dublin Horse Show has an array of national & international show jumping competitions and world class equestrian entertainment, great shopping, delicious food, music & fantastic daily entertainment. There are over 130 classes at the Show and they can be generally categorised into the following types of equestrian competitions: showing classes, performance classes and showjumping classes.- The first show was held in 1864 under the auspices of the Society, but organised by the Royal Agricultural Society of Ireland.

- There were 366 entries in the first Show with a total prize fund of £520.

- On the 28, 29 and 30 July 1868 the first show was held and organised by the Royal Dublin Society on the lawns of Leinster House. The Council granted £100 out of the Society's funds to be awarded in prizes. It started as a show of led-horses and featured ‘leaping' demonstrations.

- The first prize for the Stone Wall competition (6ft) in 1868 was won by Richard Flynn on hunter, Shane Rhue (who sold for £1,000 later that day).

- Ass and mule classes were listed at the first show!

- In 1869 the first Challenge Cup was presented for the best exhibit in the classes for hunters and young horses likely to make hunters.

- In 1870 the Show was named ‘The National Horse Show', taking place on the 16-19 August. It was combined with the Annual Sheep Show organised by the Society.

- 1869 was the year ‘horse leaping' came to prominence. There was the high leap over hurdles trimmed with gorse; the wall jump over a loose stone wall of progressive height not exceeding 6 feet; and the wide leap over 2 ½ ft gorse-filled hurdle with 12 ft of water on the far side.

- The original rules for the leaping competitions were simply ‘the obstacles had to be cleared to the satisfaction of the judges'.

- The prizes for the high and wide leaps were £5 for first and £2 for second with £10 and a cup to the winner of the championship and a riding crop and a fiver to the runner up.

- In 1881 the Show moved to ‘Ball's Bridge', a greenfield site. The first continuous ‘leaping' course was introduced at the Show.

- In 1881 the first viewing stand was erected on the site of the present Grand Stand. It held 800 people.

- With over 800 entries in the Show in 1895, it was necessary to run the jumping competitors off in pairs - causing difficulties for the judges at the time!

- Women first took part in jumping competitions from 1919.

- A class for women was introduced that year on the second day of the Show (Wednesday was the second day of the Show in 1919. Ladies' Day moved to Thursday, the second day, when the Show went from six to five days). Quickly after that, from the 1920s onwards, women were able to compete freely in many competitions at the Show.

- Women competed in international competitions representing their country shortly after WWII.

- As the first "Ladies' Jumping Competition" was held on the second day of the Show this day become known as Ladies' Day. A name that has stuck ever since.

- In 1925 Colonel Zeigler of the Swiss Army first suggested holding an international jumping event. The Aga Khan of the time heard of this proposal and offered a challenge trophy to the winner of the competition.

- In 1926 International Competitions were introduced to the show and was the first time the Nations' Cup for the Aga Khan Challenge trophy was held.

- Six countries competed in the first international teams competition for the Aga Khan Challenge trophy - Great Britain, Holland, Belgium, France, Switzerland and Ireland. The Swiss team won the title on Irish bred horses.

- The Swiss team won out the original trophy in 1930. Ireland won the first replacement in 1937 and another in 1979, Britain in 1953 and 1975. The present trophy is the sixth in the series and was presented by His Highness the Aga Khan in 1980.

- Up until 1949 the Nations' Cup teams had to consist of military officers.

- The first Grand Prix (Irish Trophy) held in 1934 was won by Comdt.J.D.(Jed) O'Dwyer, of the Army Equitation school. The Irish Trophy becomes the possession of the rider if it is won three times in succession or four times in all.

- The first timed jumping competition was held in 1938. In 1951 an electric clock was installed and the time factor entered most competitions.

- In 1976, after 50 years of international competition, the two grass banks in the Arena were removed so the Arena could be used for other events. The continental band at the western end of the Main Arena was added later.

- Shows have been held annually except from 1914-1919 due to WW1 and from 1940-1946 due to WW2.

- In 2003 the Nations Cup Competition for the Aga Khan Trophy became part of the Samsung Super League under the auspices of the Federation Equestre Internationale.

- The Nations Cup Competition for the Aga Khan Trophy is part of the Longines FEI Jumping Nations Cup™ Series.

- The Dublin Horse Show is Ireland's largest equestrian event, and one of the largest events held on the island.

- The Show has one of the largest annual prize pools for international show jumping in the world.

-

Art and craft classes were held at the Maze,Long Kesh Prison & prisons in the South as part of educational programmes, some by the prison authorities and some by the prisoners themselves. Prisoners could gain qualifications and formal courses in art history were also offered. In addition, arts and crafts were pursued at an informal level within the prison. Murals were painted on the walls of both the H-Blocks and the Nissen huts within the cages/ compounds. Handicrafts made in the prison could be sold on the ‘outside’, with proceeds going to prisoners’ families. In 1996 the Prison Arts Foundation (PAF) was founded, with the aim of providing access to the arts for all prisoners, ex-prisoners, young offenders and ex-young offenders in Northern Ireland. During the latter years of the Maze and Long Kesh Prison, the PAF promoted access to the arts by organising professional artist residencies and workshops in the H-Blocks. Security considerations placed constraints on materials permitted and the type of art and crafts that could be produced in the prison. For example, glass and ‘inflammable’ paint were not allowed. However, the availability of tools and materials varied across the site and over the years. And prisoners also improvised with materials to hand.

Art and craft classes were held at the Maze,Long Kesh Prison & prisons in the South as part of educational programmes, some by the prison authorities and some by the prisoners themselves. Prisoners could gain qualifications and formal courses in art history were also offered. In addition, arts and crafts were pursued at an informal level within the prison. Murals were painted on the walls of both the H-Blocks and the Nissen huts within the cages/ compounds. Handicrafts made in the prison could be sold on the ‘outside’, with proceeds going to prisoners’ families. In 1996 the Prison Arts Foundation (PAF) was founded, with the aim of providing access to the arts for all prisoners, ex-prisoners, young offenders and ex-young offenders in Northern Ireland. During the latter years of the Maze and Long Kesh Prison, the PAF promoted access to the arts by organising professional artist residencies and workshops in the H-Blocks. Security considerations placed constraints on materials permitted and the type of art and crafts that could be produced in the prison. For example, glass and ‘inflammable’ paint were not allowed. However, the availability of tools and materials varied across the site and over the years. And prisoners also improvised with materials to hand. -

26cm diametre Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler loved Irish folk music, and historical photographs reveal that famous Irish musician Sean Dempsey played for him in 1936. Dempsey, an uileann piper, was invited to play for Hitler and propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels during a visit to Berlin in 1936 after being told that Hitler was an Irish folk music fan. When he arrived to play, however, there was no room for him to sit, which he needed to do to play, and it looked like it would be canceled. However, Hitler jumped up and demanded that an S.S. member get down on his hands and knees and that Dempsey sit astride him while he played. Dempsey played what was described as a "haunting air" as Hitler listened with rapt attention. After he performed, Hitler presented him with a gold fountain pen while Goebbels clapped wildly. The bizarre scene was revealed for the first time in a 2010 exhibition of Irish photographs from that era called "Ceol na Cathra." The exhibition opened in Dublin and was collected by legendary fiddle player Mick O’Connor. Also in the exhibit were rare photographs from the early days of The Chieftains and Sean O'Riada, the father of modern Irish folk music.

26cm diametre Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler loved Irish folk music, and historical photographs reveal that famous Irish musician Sean Dempsey played for him in 1936. Dempsey, an uileann piper, was invited to play for Hitler and propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels during a visit to Berlin in 1936 after being told that Hitler was an Irish folk music fan. When he arrived to play, however, there was no room for him to sit, which he needed to do to play, and it looked like it would be canceled. However, Hitler jumped up and demanded that an S.S. member get down on his hands and knees and that Dempsey sit astride him while he played. Dempsey played what was described as a "haunting air" as Hitler listened with rapt attention. After he performed, Hitler presented him with a gold fountain pen while Goebbels clapped wildly. The bizarre scene was revealed for the first time in a 2010 exhibition of Irish photographs from that era called "Ceol na Cathra." The exhibition opened in Dublin and was collected by legendary fiddle player Mick O’Connor. Also in the exhibit were rare photographs from the early days of The Chieftains and Sean O'Riada, the father of modern Irish folk music. -

29cm x 20cm

29cm x 20cmBass,the former beer of choice of An Taoiseach Bertie Ahern,the Bass Ireland Brewery operated on the Glen Road in West Belfast for 107 years until its closure in 2004.But despite its popularity, this ale would be the cause of bitter controversy in the 1930s as you can learn below.

Founded in 1777 by William Bass in Burton-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, England.The main brand was Bass Pale Ale, once the highest-selling beer in the UK.By 1877, Bass had become the largest brewery in the world, with an annual output of one million barrels.Its pale ale was exported throughout the British Empire, and the company's distinctive red triangle became the UK's first registered trade mark. In the early 1930s republicans in Dublin and elsewhere waged a campaign of intimidation against publicans who sold Bass ale, which involved violent tactics and grabbed headlines at home and further afield. This campaign occurred within a broader movement calling for the boycott of British goods in Ireland, spearheaded by the IRA. Bass was not alone a British product, but republicans took issue with Colonel John Gretton, who was chairman of the company and a Conservative politician in his day.In Britain,Ireland and the Second World War, Ian Woods notes that the republican newspaper An Phoblacht set the republican boycott of Bass in a broader context , noting that there should be “No British ales. No British sweets or chocolate. Shoulder to shoulder for a nationwide boycott of British goods. Fling back the challenge of the robber empire.”

In late 1932, Irish newspapers began to report on a sustained campaign against Bass ale, which was not strictly confined to Dublin. On December 5th 1932, The Irish Times asked:

Will there be free beer in the Irish Free State at the end of this week? The question is prompted by the orders that are said to have been given to publicans in Dublin towards the end of last week not to sell Bass after a specified date.

The paper went on to claim that men visited Dublin pubs and told publicans “to remove display cards advertising Bass, to dispose of their stock within a week, and not to order any more of this ale, explaining that their instructions were given in furtherance of the campaign to boycott British goods.” The paper proclaimed a ‘War on English Beer’ in its headline. The same routine, of men visiting and threatening public houses, was reported to have happened in Cork.

It was later reported that on November 25th young men had broken into the stores owned by Bass at Moore Lane and attempted to do damage to Bass property. When put before the courts, it was reported that the republicans claimed that “Colonel Gretton, the chairman of the company, was a bitter enemy of the Irish people” and that he “availed himself of every opportunity to vent his hate, and was an ardent supporter of the campaign of murder and pillage pursued by the Black and Tans.” Remarkably, there were cheers in court as the men were found not guilty, and it was noted that they had no intention of stealing from Bass, and the damage done to the premises amounted to less than £5.

A campaign of intimidation carried into January 1933, when pubs who were not following the boycott had their signs tarred, and several glass signs advertising the ale were smashed across the city. ‘BOYCOTT BRITISH GOODS’ was painted across several Bass advertisements in the city.

Throughout 1933, there were numerous examples of republicans entering pubs and smashing the supply of Bass bottles behind the counter. This activity was not confined to Dublin,as this report from late August shows. It was noted that the men publicly stated that they belonged to the IRA.

September appears to have been a particularly active period in the boycott, with Brian Hanley identifying Dublin, Tralee, Naas, Drogheda and Waterford among the places were publicans were targetted in his study The IRA: 1926-1936. One of the most interesting incidents occurring in Dun Laoghaire. There, newspapers reported that on September 4th 1933 “more than fifty young men marched through the streets” before raiding the premises of Michael Moynihan, a local publican. Bottles of Bass were flung onto the roadway and advertisements destroyed. Five young men were apprehended for their role in the disturbances, and a series of court cases nationwide would insure that the Bass boycott was one of the big stories of September 1933.

The young men arrested in Dun Laoghaire refused to give their name or any information to the police, and on September 8th events at the Dublin District Court led to police baton charging crowds. The Irish Times reported that about fifty supporters of the young men gathered outside the court with placards such as ‘Irish Goods for Irish People’, and inside the court a cry of ‘Up The Republic!’ led to the judge slamming the young men, who told him they did not recognise his court. The night before had seen some anti-Bass activity in the city, with the smashing of Bass signs at Burgh Quay. This came after attacks on pubs at Lincoln Place and Chancery Street. It wasn’t long before Mountjoy and other prisons began to home some of those involved in the Boycott Bass campaign, which the state was by now eager to suppress.

An undated image of a demonstration to boycott British goods. Credit: http://irishmemory.blogspot.ie/

This dramatic court appearance was followed by similar scenes in Kilmainham, where twelve men were brought before the courts for a raid on the Dead Man’s Pub, near to Palmerstown in West Dublin. Almost all in their 20s, these men mostly gave addresses in Clondalkin. Their court case was interesting as charges of kidnapping were put forward, as Michael Murray claimed the men had driven him to the Featherbed mountain. By this stage, other Bass prisoners had begun a hungerstrike, and while a lack of evidence allowed the men to go free, heavy fines were handed out to an individual who the judge was certain had been involved.

The decision to go on hungerstrike brought considerable attention on prisoners in Mountjoy, and Maud Gonne MacBride spoke to the media on their behalf, telling the Irish Press on September 18th that political treatment was sought by the men. This strike had begun over a week previously on the 10th, and by the 18th it was understood that nine young men were involved. Yet by late September, it was evident the campaign was slowing down, particularly in Dublin.

The controversy around the boycott Bass campaign featured in Dáil debates on several occasions. In late September Eamonn O’Neill T.D noted that he believed such attacks were being allowed to be carried out “with a certain sort of connivance from the Government opposite”, saying:

I suppose the Minister is aware that this campaign against Bass, the destruction of full bottles of Bass, the destruction of Bass signs and the disfigurement of premises which Messrs. Bass hold has been proclaimed by certain bodies to be a national campaign in furtherance of the “Boycott British Goods” policy. I put it to the Minister that the compensation charges in respect of such claims should be made a national charge as it is proclaimed to be a national campaign and should not be placed on the overburdened taxpayers in the towns in which these terrible outrages are allowed to take place with a certain sort of connivance from the Government opposite.

Another contribution in the Dáil worth quoting came from Daniel Morrissey T.D, perhaps a Smithwicks man, who felt it necessary to say that we were producing “an ale that can compare favourably with any ale produced elsewhere” while condemning the actions of those targeting publicans:

I want to say that so far as I am concerned I have no brief good, bad, or indifferent, for Bass’s ale. We are producing in this country at the moment—and I am stating this quite frankly as one who has a little experience of it—an ale that can compare favourably with any ale produced elsewhere. But let us be quite clear that if we are going to have tariffs or embargoes, no tariffs or embargoes can be issued or given effect to in this country by any person, any group of persons, or any organisation other than the Government elected by the people of the country.

Tim Pat Coogan claims in his history of the IRA that this boycott brought the republican movement into conflict with the Army Comrades Association, later popularly known as the ‘Blueshirts’. He claims that following attacks in Dublin in December 1932, “the Dublin vitners appealed to the ACA for protection and shipments of Bass were guarded by bodyguards of ACA without further incident.” Yet it is undeniable there were many incidents of intimidation against suppliers and deliverers of the product into 1933.

Not all republicans believed the ‘Boycott Bass’ campaign had been worthwhile. Patrick Byrne, who would later become secretary within the Republican Congress group, later wrote that this was a time when there were seemingly bigger issues, like mass unemployment and labour disputes in Belfast, yet:

In this situation, while the revolution was being served up on a plate in Belfast, what was the IRA leadership doing? Organising a ‘Boycott Bass’ Campaign. Because of some disparaging remarks the Bass boss, Colonel Gretton, was reported to have made about the Irish, some IRA leaders took umbrage and sent units out onto the streets of Dublin and elsewhere to raid pubs, terrify the customers, and destroy perfectly good stocks of bottled Bass, an activity in which I regret to say I was engaged.

Historian Brian Hanley has noted by late 1933 “there was little effort to boycott anything except Bass and the desperation of the IRA in hoping violence would revive the campaign was in fact an admission of its failure. At the 1934 convention the campaign was quietly abandoned.”

Interestingly, this wasn’t the last time republicans would threaten Bass. In 1986 The Irish Times reported that Bass and Guinness were both threatened on the basis that they were supplying to British Army bases and RUC stations, on the basis of providing a service to security forces.

-

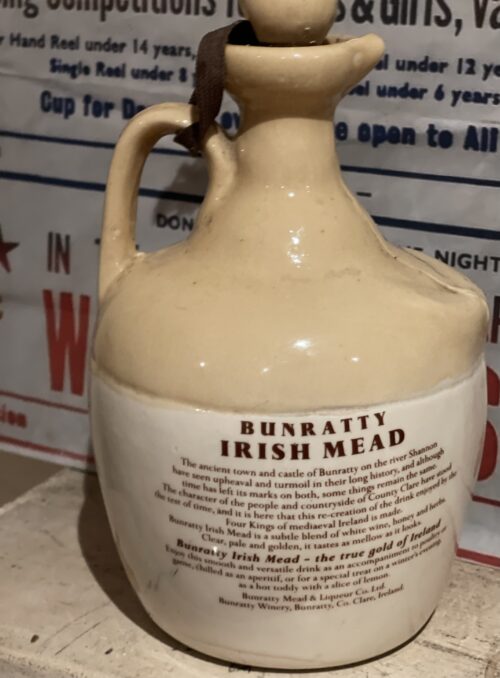

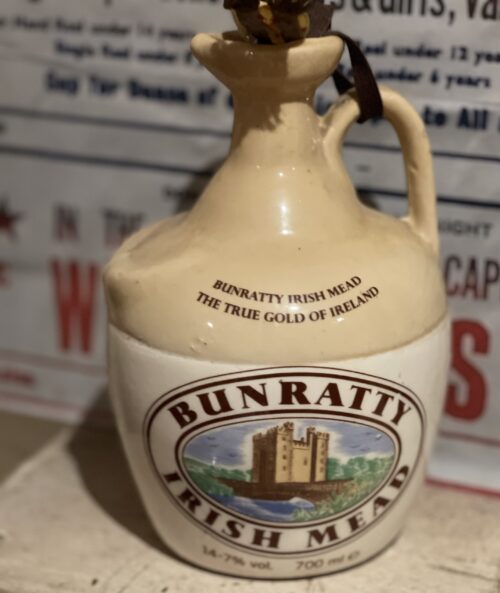

26cm (empty)

26cm (empty)Bunratty Mead is a traditional wine, produced from an ancient Irish recipe of pure honey, fruit of the vine and natural herbs. It's a medium sweet wine, with a wide taste appeal, and suitable for all important occasions. As the drink of the ancient Celts, Mead derives much of its appeal through Irish Folklore, which is legendary of this mystical drink with strong attachments to Ireland.

In the days of old when knights were bold, the drink of choice was mead. Much more than an extraordinary legendary drink with strong attachments to Ireland, mead can be traced back as many centuries before Christ. It became the chief drink of the Irish and was often referred to in Gaelic poetry. Mead's influence was so great that the halls of Tara, where the High Kings of Ireland ruled, were called the house of the Mead Circle. Its fame spread quickly and soon a medieval banquet was not complete without it.

Even the church recognised the value of this fabulous drink. Legend has it that St. Finian lived for six days a week on bread and water, but on Sundays ate salmon and drank a full sup of mead. In addition, St. Bridget performed a miracle when mead could not be located for the king of Leinster. She blessed an empty vessel, which miraculously filled with Mead.

-

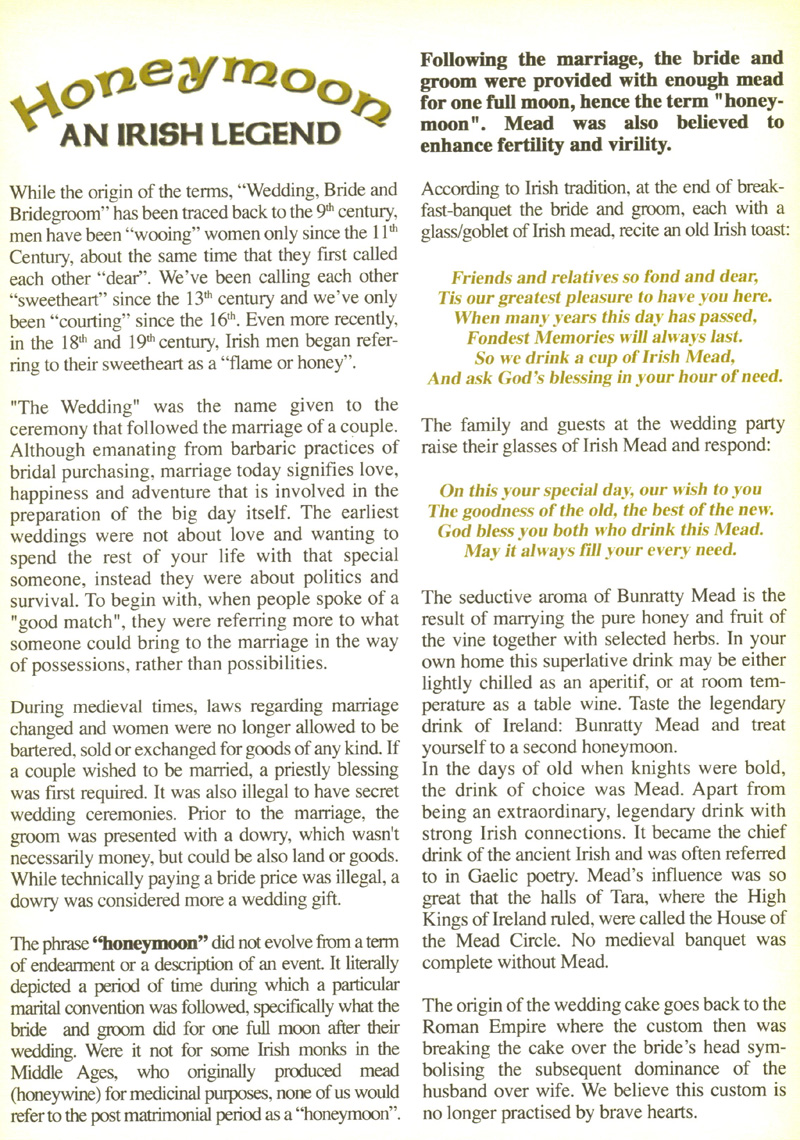

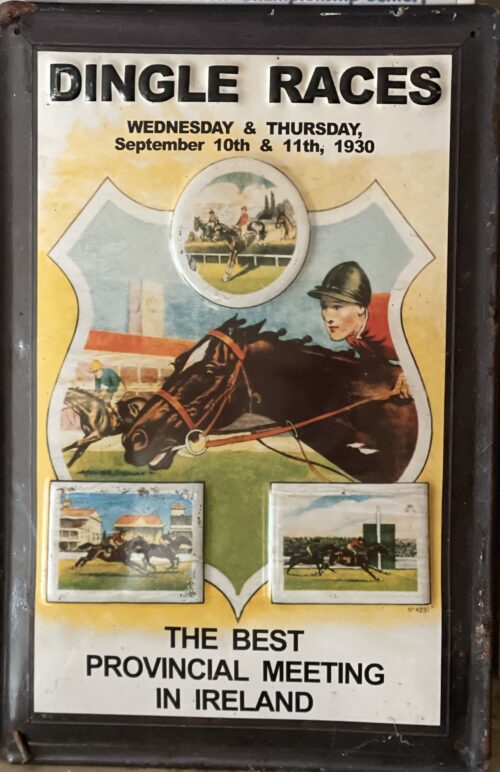

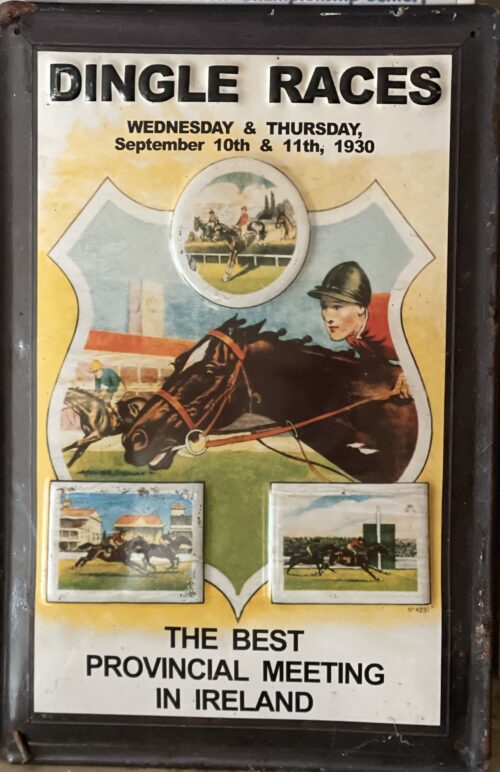

29cm x 20cm Ireland’s Largest & Best Horse & Pony Meeting. Every year in August, the field at Ballintaggart changes into an enormous racetrack filled with horses, jockeys and horse racing enthusiasts from all over Ireland and the rest of the world. No less than 20 races are held with a total prize fund of €40,000! The centre of the racecourse is filled with bouncing castles, fortune-tellers and fair stands that sell everything from bouncing balls to saddler's sponges. Entertainment for the whole family!

29cm x 20cm Ireland’s Largest & Best Horse & Pony Meeting. Every year in August, the field at Ballintaggart changes into an enormous racetrack filled with horses, jockeys and horse racing enthusiasts from all over Ireland and the rest of the world. No less than 20 races are held with a total prize fund of €40,000! The centre of the racecourse is filled with bouncing castles, fortune-tellers and fair stands that sell everything from bouncing balls to saddler's sponges. Entertainment for the whole family! -

75cm x 65cmThe biggest cliché in the collecting world is the “discovery” of a previously unknown cache of stuff that’s been hidden away for years until one day, much to everyone’s amazement, the treasure trove is unearthed and the collecting landscape is changed forever. As a corollary to this hoary trope, if you are in the right place at the right time, you can get in on the action before the word gets out.

75cm x 65cmThe biggest cliché in the collecting world is the “discovery” of a previously unknown cache of stuff that’s been hidden away for years until one day, much to everyone’s amazement, the treasure trove is unearthed and the collecting landscape is changed forever. As a corollary to this hoary trope, if you are in the right place at the right time, you can get in on the action before the word gets out.“Some of the canvases were 80 years old, dating from 1930.”

Cliché or not, that’s roughly what happened in 2008 when hundreds of artist John Gilroy’s oil-on-canvas paintings started to appear on the market. The canvases had been painted by Gilroy as final proofs for his iconic Guinness beer posters, the most recognized alcoholic-beverage advertisements of the mid-20th century. Before most collectors of advertising art and breweriana knew what had happened, most of the best pieces had been snapped up by a handful of savvy collectors. In fact, the distribution of the canvases into the hands of private collectors was so swift and stealthy that one prominent member of the Guinness family was forced to get their favorite Gilroys on the secondary market.One of those early collectors, who wishes to remain anonymous, recalls seeing several canvases for the first time at an antiques show. At first, he thought they were posters since that’s what Guinness collectors have come to expect. But after looking at them more closely, and realizing they were all original paintings, he purchased the lot on the spot. “It was quite exciting to stumble upon what appeared to be the unknown original advertising studies for one of the world’s great brands,” he says. But the casualness of that first encounter would not last, as competition for the newly found canvases ramped up among collectors. Today, the collector describes the scramble for these heretofore-unknown pieces as “a Gilroy art scrum.”Among those who were particularly interested in the news of the Gilroy cache was David Hughes, who was a brewer at Guinness for 15 years and has written three books on Guinness advertising art and collectibles, the most recent being “Gilroy Was Good for Guinness,” which reproduces more than 150 of the recently “discovered” paintings. Despite being an expert on the cheery ephemera that was created to sell the dark, bitter stout, Hughes, like a lot of people, only learned of the newly uncovered Gilroy canvases as tantalizing examples from the cache (created for markets as diverse as Russia, Israel, France, and the United States) started to surface in 2008.“Within the Guinness archives itself,” Hughes says of the materials kept at the company’s Dublin headquarters, “they’ve got lots of advertising art, watercolors, and sketches of workups towards the final version of the posters. But they never had a single oil painting. Until the paintings started turning up in the United States, where Guinness memorabilia is quite collectible, it wasn’t fully understood that the posters were based on oils. All of the canvases will be in collections within a year,” Hughes adds. For would-be Gilroy collectors, that means the clock is ticking.As it turns out, Gilroy’s entire artistic process was a prelude to the oils. “The first thing he’d usually do was a pencil sketch,” says Hughes. “Then he’d paint a watercolor over the top of the pencil sketch to get the color balance right. Once that was settled and all the approvals were in, he’d sit down and paint the oil. The proof version that went to Guinness for approval, it seems, was always an oil painting.”Based on what we know of John Gilroy’s work as an artist, that makes sense. For almost half a century, Gilroy was regarded not only as one of England’s premier commercial illustrators, but also as one of its best portraitists. “He painted the Queen three times,” says Hughes, “Lord Mountbatten about four times. In 1942, he did a pencil-and-crayon sketch of Churchill in a London bunker.” According to Hughes, Churchill gave that portrait to Russian leader Joseph Stalin at the Yalta Conference with Franklin Delano Roosevelt, which may mean that somewhere in the bowels of the Kremlin, there’s a portrait of Winnie by the same guy who made a living drawing cartoons of flying toucans balancing pints of Guinness on their beaks.For those who collect advertising art and breweriana, Gilroy is revered for the numerous campaigns he conceived as an illustrator for S.H. Benson, the venerable British ad agency, which was founded in 1893. Though most famous for the Guinness toucan, which has been the internationally recognized mascot of Guinness since 1935, Gilroy’s first campaign with S.H. Benson was for a yeast extract called Bovril. “Do you have Bovril in the U.S.?” Hughes asks. “It’s a rather dark, pungent, savory spread that goes on toast or bread. It’s full of vitamins, quite a traditional product. He also did a lot of work on campaigns for Colman’s mustard and Macleans toothpaste.”pparently Gilroy’s work caught the eye of Guinness, which wanted something distinctive for its stout. “A black beer is a unique product,” says Hughes. “There weren’t many on the market then, and there are even fewer now. So they wanted their advertising to be well thought of and agreeable to the public.” For example, in the early 1930s, Benson already had an ad featuring a glass of Guinness with a nice foamy head on top. “Gilroy put a smiling face in the foam,” says Hughes. Collectors often refer to this charming drawing as the “anthropomorphic glass.”That made the black beer friendly. To ensure that it would be appealing to the common man, Benson launched its “Guinness for Strength” campaign, whose most famous image is the 1934 Gilroy illustration of a muscular workman effortlessly balancing an enormous steel girder on one arm and his head.Another early campaign put Guinness beer in the world of Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.” “Guinness and oysters were a big thing,” says Hughes. In one ad, “Gilroy drew all the oysters from the poem ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’ sipping glasses of Guinness.”nd then there were the animals, of which the toucan is only the most recognized, and not even the first (that honor goes to a seal). “He had the lion and the ostrich and the bear up the pole,” Hughes says. “There was a whole menagerie of them. The animals kept going for 30 years. It’s probably the longest running campaign in advertising history.”Most of Gilroy’s animals lived in a zoo, so a central character of the animal advertisements was a zookeeper, who was a caricature of the artist himself. “That’s what Gilroy looked like,” says Hughes. “Gilroy was a chubby, little man with a little moustache. As a younger man, he drew himself into the advert, and he became the zookeeper.”Gilroy’s animals good-naturedly tormented their zookeeper by stealing his precious Guinness: An ostrich swallows his glass pint whole, whose bulging outline can be seen in its slender throat; a seal balances a pint on its nose; a kangaroo swaps her “joey” for the zookeeper’s brown bottle. Often the zookeeper is so taken aback by these circumstances his hat has popped off his head.In fact, Gilroy spent a lot of time at the London Zoo to make sure he captured the essence of his animals accurately. “In the archives at Guinness,” says Hughes, “there are a lot of sketches of tortoises, emus, ostriches, and the rest. He perfected the drawing of the animals by going to the zoo, then he adapted them for the adverts.” As a result, a Gilroy bear really looked like a bear, albeit one with a smile on its face.During World War II, Gilroy’s Guinness ads managed to keep their sense of humor (eg: two sailors painting the hull of an aircraft carrier, each wishing the other was a Guinness), and in the 1950s and early ’60s, Gilroy’s famous pint-toting toucans flew all over the world for Guinness, in front of the Kremlin as well as Mt. Rushmore, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, and the Statue of Liberty, although some of these paintings never made it to the campaign stage.Gilroy’s work on the Guinness account ended in 1962, and in 1971, Benson was gobbled up by the Madison Avenue advertising firm of Ogilvy & Mather. By then, says Hughes, Gilroy’s work for Guinness was considered the pinnacle of poster design in the U.K., and quite collectible. “The posters were made by a lithographic process. In the 1930s, the canvases were re-created on stone by a print maker, but eventually the paintings were transferred via photolithography onto metal sheets. Some of the biggest posters were made for billboards. Those used 64 different sheets that you’d give to the guy with the bucket of wheat paste and a mop to put up in the right order to create the completed picture.”In terms of single-sheet posters, Hughes says the biggest ones were probably 4 by 3 feet. Benson’s had an archive of it all, but “when Benson’s shut down in ’71, when they were taken over, they cleaned out their stockroom of hundreds of posters and gave them to the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Today, both have collections of the original posters, including the 64-sheets piled into these packets, which were wrapped in brown paper and tied up with string. They’re extremely difficult to handle; you can’t display them, really.”At least the paper got a good home. As for the canvases? Well, their history can only be pieced together based on conjecture, but here’s what Hughes thinks he knows.Sometime in the 1970s, a single collector whose name remains a mystery appears to have purchased as many as 700 to 900 Gilroy paintings that had been in the archives. “The guy who bought the whole archive was an American millionaire,” Hughes says. “He’s a secretive character who doesn’t want to be identified. I don’t blame him. He doesn’t want any publicity about how he bought the collection or its subsequent sale.”air enough. What we do know for sure is that the years were not kind to Gilroy’s canvases while in storage at Benson’s. In fact, it’s believed that more than half of the cache did not survive the decades and were probably destroyed by the mystery collector who bought them because of their extremely deteriorated condition (torn canvases, images blackened by mildew, etc.). After all, when Gilroy’s canvases were put away, no one at Benson’s thought they’d be regarded in the future as masterpieces.“A lot of the rolled-up canvases were stuck together,” says Hughes. “Oil takes a long while to dry. Gilroy diluted his oils with what’s called Japan drier, which is a sort of oil thinner that allows you to put the oil on the canvas in a much thinner texture, and then roll them up afterwards. The painted canvas becomes reasonably flexible. The problem is that even with a drier, they still took a long time to dry. And if someone had packed them tightly together and put weight on them, which is what must have happened while the Gilroy paintings were in storage at Benson’s, they’d just stick together. Some of the canvases were 80 years old, dating from 1930.”For diehard Guinness-advertising fans, though, it’s not all bad news. After all, almost half of the cache was saved, “and it’s beautiful,” says Hughes. “I’ve just come back from Boston to look at a lot of these canvases out there, and they are superb. The guy who’s selling the canvases I saw had about 40 or 50 with him. They’re absolutely fabulous.”Although he has no proof, Hughes believes the person who bought the cache in the 1970s also oversaw its preservation. Importantly to many collectors, all of the Gilroy canvases are in their found condition, stabilized but essentially unchanged. Even areas in the paint that show evidence of rubbing from adjacent canvases remain as they were found. “I think the preservation has been done by the owner,” Hughes says. “I don’t think the dealers did it. It’s my understanding that they were supplied with fully stabilized canvases from the original buyer. It appears that they were shipped from the U.K., so that’s interesting in itself.” Which suggests they never left the United Kingdom after being purchased by the mysterious American millionaire.collectors of the approval process at Benson. Gilroy painted his canvases on stretchers, and in the bottom corner of each canvas was a small tag identifying the artist, account code, and action to be taken (“Re-draw,” “Revise,” “Hold,” “Print,” and, during World War II, “Submit to censor”). “They would’ve been shown to Guinness on a wooden stretcher,” Hughes says. “Before they went into storage, somebody removed the stretchers and either laid them flat or rolled them up.”“As a younger man, he drew himself into the advert, and he became the zookeeper.”

Without exception, the canvases Hughes has seen, which were photographed exclusively for his book, are in fine shape and retain their mounting holes for the stretchers and Benson agency tags. “The colors are good,” he says. “They haven’t been in sunlight. They’ll keep for years and years and years.” One collector notes that you can even see the ruby highlights in Gilroy’s paintings of glasses of the stout. “When a pint of Guinness is backlit by a very strong light, the liquid has a deep ruby color,” this collector says. “Gilroy was very careful to include this effect when he painted beer in clear pint glasses.”Finally, for Guinness, breweriana, and advertising-art collectors, the Gilroy canvases also offer a peek of what might have been. “I would say about half the images were never commercially used, so they are absolutely brand new, never been seen before,” says Hughes. “They’re going to blow people away.” Of particular interest to collectors in the United States are the Gilroy paintings of classic cars that were created for an aborted, early 1950s campaign to coincide with the brewing of Guinness on Long Island.Still, it’s the medium that continues to amaze Hughes. “The idea of the canvases, none of us expected that,” he says. “As a Guinness collector, I’ve always collected their adverts, but they’re prints. They never touched Gilroy, he was never anywhere near the printing process. I had acquired a pencil drawing, which I was delighted with. Then these oils started turning up,” he Naturally, Hughes the Guinness scholar has seen a few oils that Hughes the Guinness collector would very much like to own. “If I had a magic wand? Well, I saw one this weekend that I really liked. It’s one of the animal ones. But it’s an animal that was not used commercially. It’s of a rhinoceros sitting on the ground with the zookeeper’s Guinness between his legs. The rhinoceros is looking at the zookeeper, and the zookeeper’s looking around the corner holding his broom. It’s just a great image, and it’s probably the only one of that advert that exists. So if I could wave my magic wand, I think that’s what I’d get. But I’d need $10,000With those kinds of prices and that kind of buzz, you might think that whoever is handling the Guinness advertising account today might be tempted to just re-run the campaign. But Hughes is realistic about the likelihood of that. “Advertising moves on,” he says. “Gilroy’s jokey, humorous, cartoon-like poster design is quintessentially 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. It is a bit quaint, maybe even a little juvenile for today’s audiences. But it’s still amusing. The other day I showed the draft of my book to my mother, who’s 84. She sat in the kitchen, just giggling at the pictures.”That sums up Gilroy to Hughes; not that it’s only appealing to people in their 80s, but that his work is ultimately about making people happy, which is why his advertising images connected so honestly with viewers. “Gilroy had a tremendous sense of humor,” Hughes says. “He always saw the funny side of things. He was apparently a chap who, if you were feeling a little down and out, you’d spend a couple of hours with him and he’d just lift your spirits.” You know, in much the same way as a lot of us feel after a nice pint of Guinness.