Bass,the former beer of choice of An Taoiseach Bertie Ahern,the Bass Ireland Brewery operated on the Glen Road in West Belfast for 107 years until its closure in 2004.But despite its popularity, this ale would be the cause of bitter controversy in the 1930s as you can learn below.

Founded in 1777 by William Bass in Burton-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, England.The main brand was Bass Pale Ale, once the highest-selling beer in the UK.By 1877, Bass had become the largest brewery in the world, with an annual output of one million barrels.Its pale ale was exported throughout the British Empire, and the company's distinctive red triangle became the UK's first registered trade mark. In the early 1930s republicans in Dublin and elsewhere waged a campaign of intimidation against publicans who sold Bass ale, which involved violent tactics and grabbed headlines at home and further afield. This campaign occurred within a broader movement calling for the boycott of British goods in Ireland, spearheaded by the IRA. Bass was not alone a British product, but republicans took issue with Colonel John Gretton, who was chairman of the company and a Conservative politician in his day.In Britain,Ireland and the Second World War, Ian Woods notes that the republican newspaper An Phoblacht set the republican boycott of Bass in a broader context , noting that there should be “No British ales. No British sweets or chocolate. Shoulder to shoulder for a nationwide boycott of British goods. Fling back the challenge of the robber empire.”

In late 1932, Irish newspapers began to report on a sustained campaign against Bass ale, which was not strictly confined to Dublin. On December 5th 1932, The Irish Times asked:

Will there be free beer in the Irish Free State at the end of this week? The question is prompted by the orders that are said to have been given to publicans in Dublin towards the end of last week not to sell Bass after a specified date.

The paper went on to claim that men visited Dublin pubs and told publicans “to remove display cards advertising Bass, to dispose of their stock within a week, and not to order any more of this ale, explaining that their instructions were given in furtherance of the campaign to boycott British goods.” The paper proclaimed a ‘War on English Beer’ in its headline. The same routine, of men visiting and threatening public houses, was reported to have happened in Cork.

It was later reported that on November 25th young men had broken into the stores owned by Bass at Moore Lane and attempted to do damage to Bass property. When put before the courts, it was reported that the republicans claimed that “Colonel Gretton, the chairman of the company, was a bitter enemy of the Irish people” and that he “availed himself of every opportunity to vent his hate, and was an ardent supporter of the campaign of murder and pillage pursued by the Black and Tans.” Remarkably, there were cheers in court as the men were found not guilty, and it was noted that they had no intention of stealing from Bass, and the damage done to the premises amounted to less than £5.

A campaign of intimidation carried into January 1933, when pubs who were not following the boycott had their signs tarred, and several glass signs advertising the ale were smashed across the city. ‘BOYCOTT BRITISH GOODS’ was painted across several Bass advertisements in the city.

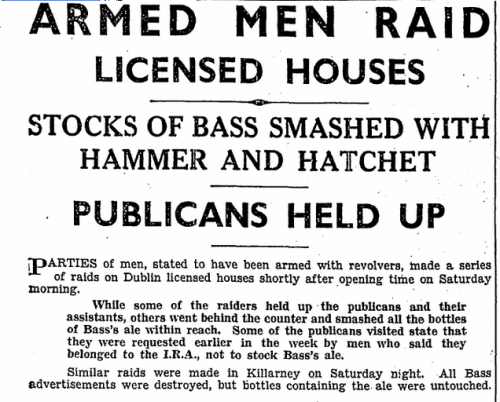

Throughout 1933, there were numerous examples of republicans entering pubs and smashing the supply of Bass bottles behind the counter. This activity was not confined to Dublin,as this report from late August shows. It was noted that the men publicly stated that they belonged to the IRA.

September appears to have been a particularly active period in the boycott, with Brian Hanley identifying Dublin, Tralee, Naas, Drogheda and Waterford among the places were publicans were targetted in his study The IRA: 1926-1936. One of the most interesting incidents occurring in Dun Laoghaire. There, newspapers reported that on September 4th 1933 “more than fifty young men marched through the streets” before raiding the premises of Michael Moynihan, a local publican. Bottles of Bass were flung onto the roadway and advertisements destroyed. Five young men were apprehended for their role in the disturbances, and a series of court cases nationwide would insure that the Bass boycott was one of the big stories of September 1933.

The young men arrested in Dun Laoghaire refused to give their name or any information to the police, and on September 8th events at the Dublin District Court led to police baton charging crowds. The Irish Times reported that about fifty supporters of the young men gathered outside the court with placards such as ‘Irish Goods for Irish People’, and inside the court a cry of ‘Up The Republic!’ led to the judge slamming the young men, who told him they did not recognise his court. The night before had seen some anti-Bass activity in the city, with the smashing of Bass signs at Burgh Quay. This came after attacks on pubs at Lincoln Place and Chancery Street. It wasn’t long before Mountjoy and other prisons began to home some of those involved in the Boycott Bass campaign, which the state was by now eager to suppress.

An undated image of a demonstration to boycott British goods. Credit: http://irishmemory.blogspot.ie/

This dramatic court appearance was followed by similar scenes in Kilmainham, where twelve men were brought before the courts for a raid on the Dead Man’s Pub, near to Palmerstown in West Dublin. Almost all in their 20s, these men mostly gave addresses in Clondalkin. Their court case was interesting as charges of kidnapping were put forward, as Michael Murray claimed the men had driven him to the Featherbed mountain. By this stage, other Bass prisoners had begun a hungerstrike, and while a lack of evidence allowed the men to go free, heavy fines were handed out to an individual who the judge was certain had been involved.

The decision to go on hungerstrike brought considerable attention on prisoners in Mountjoy, and Maud Gonne MacBride spoke to the media on their behalf, telling the Irish Press on September 18th that political treatment was sought by the men. This strike had begun over a week previously on the 10th, and by the 18th it was understood that nine young men were involved. Yet by late September, it was evident the campaign was slowing down, particularly in Dublin.

The controversy around the boycott Bass campaign featured in Dáil debates on several occasions. In late September Eamonn O’Neill T.D noted that he believed such attacks were being allowed to be carried out “with a certain sort of connivance from the Government opposite”, saying:

I suppose the Minister is aware that this campaign against Bass, the destruction of full bottles of Bass, the destruction of Bass signs and the disfigurement of premises which Messrs. Bass hold has been proclaimed by certain bodies to be a national campaign in furtherance of the “Boycott British Goods” policy. I put it to the Minister that the compensation charges in respect of such claims should be made a national charge as it is proclaimed to be a national campaign and should not be placed on the overburdened taxpayers in the towns in which these terrible outrages are allowed to take place with a certain sort of connivance from the Government opposite.

Another contribution in the Dáil worth quoting came from Daniel Morrissey T.D, perhaps a Smithwicks man, who felt it necessary to say that we were producing “an ale that can compare favourably with any ale produced elsewhere” while condemning the actions of those targeting publicans:

I want to say that so far as I am concerned I have no brief good, bad, or indifferent, for Bass’s ale. We are producing in this country at the moment—and I am stating this quite frankly as one who has a little experience of it—an ale that can compare favourably with any ale produced elsewhere. But let us be quite clear that if we are going to have tariffs or embargoes, no tariffs or embargoes can be issued or given effect to in this country by any person, any group of persons, or any organisation other than the Government elected by the people of the country.

Tim Pat Coogan claims in his history of the IRA that this boycott brought the republican movement into conflict with the Army Comrades Association, later popularly known as the ‘Blueshirts’. He claims that following attacks in Dublin in December 1932, “the Dublin vitners appealed to the ACA for protection and shipments of Bass were guarded by bodyguards of ACA without further incident.” Yet it is undeniable there were many incidents of intimidation against suppliers and deliverers of the product into 1933.

Not all republicans believed the ‘Boycott Bass’ campaign had been worthwhile. Patrick Byrne, who would later become secretary within the Republican Congress group, later wrote that this was a time when there were seemingly bigger issues, like mass unemployment and labour disputes in Belfast, yet:

In this situation, while the revolution was being served up on a plate in Belfast, what was the IRA leadership doing? Organising a ‘Boycott Bass’ Campaign. Because of some disparaging remarks the Bass boss, Colonel Gretton, was reported to have made about the Irish, some IRA leaders took umbrage and sent units out onto the streets of Dublin and elsewhere to raid pubs, terrify the customers, and destroy perfectly good stocks of bottled Bass, an activity in which I regret to say I was engaged.

Historian Brian Hanley has noted by late 1933 “there was little effort to boycott anything except Bass and the desperation of the IRA in hoping violence would revive the campaign was in fact an admission of its failure. At the 1934 convention the campaign was quietly abandoned.”

Interestingly, this wasn’t the last time republicans would threaten Bass. In 1986 The Irish Times reported that Bass and Guinness were both threatened on the basis that they were supplying to British Army bases and RUC stations, on the basis of providing a service to security forces.