-

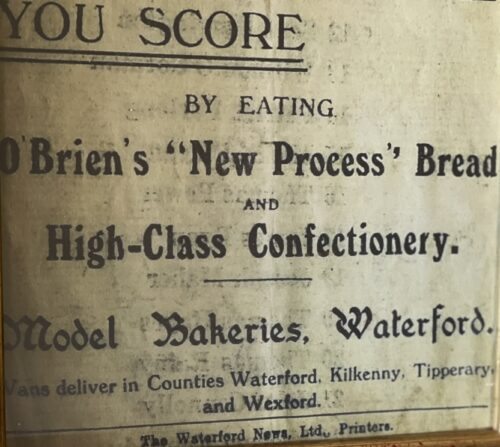

40cm x 23cm Thurles Co Tipperary The All-Ireland Junior Hurling Championship was a hurling competition organized by the Gaelic Athletic Association in Ireland. The competition was originally contested by the second teams of the strong counties, and the first teams of the weaker counties. In the years from 1961 to 1973 and from 1997 until now, the strong counties have competed for the All-Ireland Intermediate Hurling Championship instead. The competition was then restricted to the weaker counties. The competition was discontinued after 2004 as these counties now compete for the Nicky Rackard Cup instead. From 1974 to 1982, the original format of the competition was abandoned, and the competition was incorporated in Division 3 of the National Hurling League. The original format, including the strong hurling counties was re-introduced in 1983. 1930 – TIPPERARY: Paddy Harty (Captain), Tom Harty, Willie Ryan, Tim Connolly, Mick McGann, Martin Browne, Ned Wade, Tom Ryan, Jack Dwyer, Mick Ryan, Dan Looby, Pat Furlong, Bill O’Gorman, Joe Fletcher, Sean Harrington.

40cm x 23cm Thurles Co Tipperary The All-Ireland Junior Hurling Championship was a hurling competition organized by the Gaelic Athletic Association in Ireland. The competition was originally contested by the second teams of the strong counties, and the first teams of the weaker counties. In the years from 1961 to 1973 and from 1997 until now, the strong counties have competed for the All-Ireland Intermediate Hurling Championship instead. The competition was then restricted to the weaker counties. The competition was discontinued after 2004 as these counties now compete for the Nicky Rackard Cup instead. From 1974 to 1982, the original format of the competition was abandoned, and the competition was incorporated in Division 3 of the National Hurling League. The original format, including the strong hurling counties was re-introduced in 1983. 1930 – TIPPERARY: Paddy Harty (Captain), Tom Harty, Willie Ryan, Tim Connolly, Mick McGann, Martin Browne, Ned Wade, Tom Ryan, Jack Dwyer, Mick Ryan, Dan Looby, Pat Furlong, Bill O’Gorman, Joe Fletcher, Sean Harrington. -

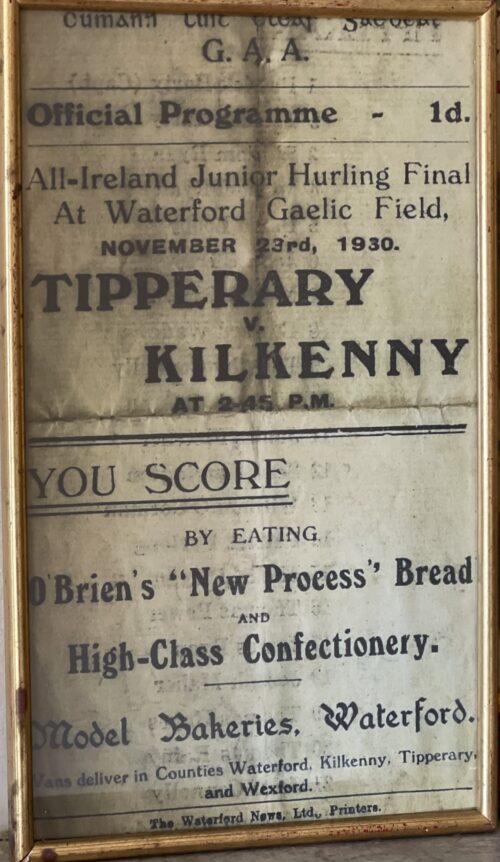

Clonakilty Co Cork 42cm x 30cm

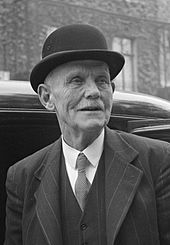

Clonakilty Co Cork 42cm x 30cmJAMES J. MURPHY

Born on November 1825, James Jeremiah Murphy was the eldest son of fifteen children born to Jeremiah James Murphy and Catherine Bullen. James J. served his time in the family business interest and was also involved in the running of a local distillery in Cork. He sold his share in this distillery to fund his share of the set up costs of the brewery in 1856. James J. was the senior partner along with his four other brothers. It was James who guided to the brewery to success in its first forty years and he saw its output grow to 100,000 barrels before his death in 1897. James J. through his life had a keen interest in sport, rowing, sailing and GAA being foremost. He was a supporter of the Cork Harbour Rowing Club and the Royal Cork Yacht Club and the Cork County Board of the GAA. James J. philanthropic efforts were also well known in the city supporting hospitals, orphanages and general relief of distress in the city so much so on his death being described as a ‘prince in the charitable world’. It is James J. that epitomises the Murphy’s brand in stature and quality of character.1854

Born on November 1825, James Jeremiah Murphy was the eldest son of fifteen children born to Jeremiah James Murphy and Catherine Bullen. James J. served his time in the family business interest and was also involved in the running of a local distillery in Cork. He sold his share in this distillery to fund his share of the set up costs of the brewery in 1856. James J. was the senior partner along with his four other brothers. It was James who guided to the brewery to success in its first forty years and he saw its output grow to 100,000 barrels before his death in 1897. James J. through his life had a keen interest in sport, rowing, sailing and GAA being foremost. He was a supporter of the Cork Harbour Rowing Club and the Royal Cork Yacht Club and the Cork County Board of the GAA. James J. philanthropic efforts were also well known in the city supporting hospitals, orphanages and general relief of distress in the city so much so on his death being described as a ‘prince in the charitable world’. It is James J. that epitomises the Murphy’s brand in stature and quality of character.1854OUR LADY’S WELL BREWERY

In 1854 James J. and his brothers purchased the buildings of the Cork foundling Hospital and on this site built the brewery. The brewery eventually became known as the Lady’s Well Brewery as it is situated adjacent to a famous ‘Holy Well’ and water source that had become a famous place of devotion during penal times.1856

In 1854 James J. and his brothers purchased the buildings of the Cork foundling Hospital and on this site built the brewery. The brewery eventually became known as the Lady’s Well Brewery as it is situated adjacent to a famous ‘Holy Well’ and water source that had become a famous place of devotion during penal times.1856THE BEGINNING

James J. Murphy and his brothers found James J. Murphy & Co. and begin brewing.1861

James J. Murphy and his brothers found James J. Murphy & Co. and begin brewing.1861FROM STRENGTH TO STRENGTH

In 1861 the brewery produced 42,990 barrels and began to impose itself as one of the major breweries in the country.1885

In 1861 the brewery produced 42,990 barrels and began to impose itself as one of the major breweries in the country.1885A FRIEND OF THE POOR, HURRAH

James J. was a much loved figure in Cork, a noted philanthropist and indeed hero of the entire city at one point. The ‘Hurrah for the hero’ song refers to James J’s heroic efforts to save the local economy from ruin in the year of 1885. The story behind this is that when the key bank for the region the ‘Munster Bank’ was close to ruin, which could have led to an economic disaster for the entire country and bankruptcy for thousands, James J. stepped in and led the venture to establish a new bank the ‘Munster and Leinster’, saving the Munster Bank depositors and creditors from financial loss and in some cases, ruin. His exploits in saving the bank, led to the writing of many a poem and song in his honour including ‘Hurrah for the man who’s a friend of the poor’, which would have been sung in pubs for many years afterwards.1889

James J. was a much loved figure in Cork, a noted philanthropist and indeed hero of the entire city at one point. The ‘Hurrah for the hero’ song refers to James J’s heroic efforts to save the local economy from ruin in the year of 1885. The story behind this is that when the key bank for the region the ‘Munster Bank’ was close to ruin, which could have led to an economic disaster for the entire country and bankruptcy for thousands, James J. stepped in and led the venture to establish a new bank the ‘Munster and Leinster’, saving the Munster Bank depositors and creditors from financial loss and in some cases, ruin. His exploits in saving the bank, led to the writing of many a poem and song in his honour including ‘Hurrah for the man who’s a friend of the poor’, which would have been sung in pubs for many years afterwards.1889THE MALT HOUSE

In 1889 a Malt House for the brewery was built at a cost of 4,640 pounds and was ‘built and arranged on the newest principle and fitted throughout with the latest appliances known to modern science”. Today the Malthouse is one of the most famous Cork landmarks and continues to function as offices for Murphy’s.1892

In 1889 a Malt House for the brewery was built at a cost of 4,640 pounds and was ‘built and arranged on the newest principle and fitted throughout with the latest appliances known to modern science”. Today the Malthouse is one of the most famous Cork landmarks and continues to function as offices for Murphy’s.1892MURPHY’S GOLD

Murphy’s Stout wins the Gold medal at the Brewers and Allied Trades Exhibition in Dublin and again wins the supreme award when the exhibition is held in Manchester in 1895. These same medals feature on our Murphy’s packaging today. Murphy’s have continued it’s tradition of excellence in brewing winning Gold again at the Brewing Industry International awards in 2002 and also gaining medals in the subsequent two competitions.1893

Murphy’s Stout wins the Gold medal at the Brewers and Allied Trades Exhibition in Dublin and again wins the supreme award when the exhibition is held in Manchester in 1895. These same medals feature on our Murphy’s packaging today. Murphy’s have continued it’s tradition of excellence in brewing winning Gold again at the Brewing Industry International awards in 2002 and also gaining medals in the subsequent two competitions.1893MURPHY’S FOR STRENGTH

Eugen Sandow the world famous ‘strongman’, endorses Murphy’s Stout: “From experience I can strongly recommend Messrs JJ Murphy’s Stout”. The famous Murphy’s image of Sandow lifting a horse was then created.1906

Eugen Sandow the world famous ‘strongman’, endorses Murphy’s Stout: “From experience I can strongly recommend Messrs JJ Murphy’s Stout”. The famous Murphy’s image of Sandow lifting a horse was then created.1906THE JUBILEE

The Brewery celebrates its 50th anniversary. On Whit Monday the brewery workforce and their families are treated to an excursion by train to Killarney. Paddy Barrett the youngest of the workforce that day at 13 went on to become head porter for the brewery and could recall the day vividly 50 years later.1913

The Brewery celebrates its 50th anniversary. On Whit Monday the brewery workforce and their families are treated to an excursion by train to Killarney. Paddy Barrett the youngest of the workforce that day at 13 went on to become head porter for the brewery and could recall the day vividly 50 years later.1913SWIMMING IN STOUT

In the year of 1913 the No.5 Vat at ‘Lady’s Well’ Brewery burst and sent 23,000 galleons of porter flooding through the brewey and out on to Leitrim Street. The Cork Constitution, the local newspaper of the time wrote that “a worker had a most exciting experience and in the onrush of porter he had to swim in it for about 40 yards to save himself from asphyxiation”1914

In the year of 1913 the No.5 Vat at ‘Lady’s Well’ Brewery burst and sent 23,000 galleons of porter flooding through the brewey and out on to Leitrim Street. The Cork Constitution, the local newspaper of the time wrote that “a worker had a most exciting experience and in the onrush of porter he had to swim in it for about 40 yards to save himself from asphyxiation”1914JOINING UP

The First World War marked an era of dramatic change both in the countries fortune and on a much smaller scale that of the Brewery’s. On the 13 August James J. Murphy and Co. joined the other members of the Cork Employers Federation in promising that ‘all constant employees volunteering to join any of his Majesties forces for active service in compliance with the call for help by the Government will be facilitated and their places given back to them at the end of the war’. Eighteen of the Brewery’s workers joined up including one sixteen year old. Ten never returned.1915

The First World War marked an era of dramatic change both in the countries fortune and on a much smaller scale that of the Brewery’s. On the 13 August James J. Murphy and Co. joined the other members of the Cork Employers Federation in promising that ‘all constant employees volunteering to join any of his Majesties forces for active service in compliance with the call for help by the Government will be facilitated and their places given back to them at the end of the war’. Eighteen of the Brewery’s workers joined up including one sixteen year old. Ten never returned.1915THE FIRST LORRY IN IRELAND

James J. Murphy & Co. purchase the first petrol lorry in the country.1920

James J. Murphy & Co. purchase the first petrol lorry in the country.1920THE BURNING OF CORK

On the 11-12th December the centre of Cork city was extensively damaged by fire including four of the company’s tied houses (Brewery owned establishments). The company was eventually compensated for its losses by the British government.1921

On the 11-12th December the centre of Cork city was extensively damaged by fire including four of the company’s tied houses (Brewery owned establishments). The company was eventually compensated for its losses by the British government.1921MURPHY’S IN A BOTTLE

In 1921 James J. Murphy and Co. open a bottling plant and bottle their own stout. A foreman and four ‘boys’ were installed to run the operation and the product quickly won ‘good trade’.1924

In 1921 James J. Murphy and Co. open a bottling plant and bottle their own stout. A foreman and four ‘boys’ were installed to run the operation and the product quickly won ‘good trade’.1924THE FIRST CAMPAIGNS

In 1924 the Murphy’s Brewery began to embrace advertising. In the decades prior to this the attitude had been somewhat negative with one director stating ‘We do not hope to thrive on pushing and puffing; our sole grounds for seeking popular favour is the excellence of our product’.1940

In 1924 the Murphy’s Brewery began to embrace advertising. In the decades prior to this the attitude had been somewhat negative with one director stating ‘We do not hope to thrive on pushing and puffing; our sole grounds for seeking popular favour is the excellence of our product’.1940WWII

In 1940 at the height of the London Blitz the Murphy’s auditing firm is completely destroyed. The war which had indirectly affected the firm in terms of shortages of fuel and materials now affected the brewery directly.1953

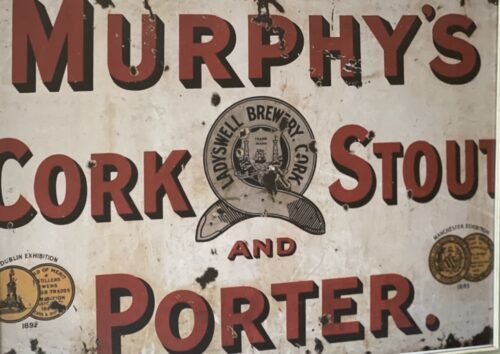

In 1940 at the height of the London Blitz the Murphy’s auditing firm is completely destroyed. The war which had indirectly affected the firm in terms of shortages of fuel and materials now affected the brewery directly.1953LT. COL JOHN FITZJAMES

In 1953 the last direct descendant of James J. takes over Chairmanship of the firm. Affectionately known in the Brewery as the ‘Colonel’ he ran the company until 1981.1961

In 1953 the last direct descendant of James J. takes over Chairmanship of the firm. Affectionately known in the Brewery as the ‘Colonel’ he ran the company until 1981.1961THE IRON LUNG

Complete replacement of old wooden barrels to aluminium lined vessels (kegs) known as ‘Iron lungs’ draws to an end the era of ‘Coopers’ the tradesmen who built the wooden barrels on site in the Brewery for so many decades.1979

Complete replacement of old wooden barrels to aluminium lined vessels (kegs) known as ‘Iron lungs’ draws to an end the era of ‘Coopers’ the tradesmen who built the wooden barrels on site in the Brewery for so many decades.1979MURPHY’S IN AMERICA

Murphy’s reaches Americans shores for the first time winning back many drinkers lost to emigration and a whole new generation of stout drinkers.

1985MURPHY’S GOES INTERNATIONAL

Murphy’s Launched as a National and International Brand. Exports included UK, US and Canada. Introduction of the first 25cl long neck stout bottle.1994

Murphy’s Launched as a National and International Brand. Exports included UK, US and Canada. Introduction of the first 25cl long neck stout bottle.1994MURPHY’S OPEN

Murphy’s commence sponsorship of the hugely successful Murphy’s Irish Open Golf Championship culminating in Colm Montgomery’s ‘Monty’s’ famous third win at ‘Fota Island’ in 2002.2005

Murphy’s commence sponsorship of the hugely successful Murphy’s Irish Open Golf Championship culminating in Colm Montgomery’s ‘Monty’s’ famous third win at ‘Fota Island’ in 2002.2005MURPHY’S GOLD

Murphy’s wins Gold at the Brewing Industry International Awards a testament to it’s superior taste and quality. Indeed 2003 was the first of three successive wins in this competition.2006

Murphy’s wins Gold at the Brewing Industry International Awards a testament to it’s superior taste and quality. Indeed 2003 was the first of three successive wins in this competition.2006150 YEARS OF BREWING LEGEND

The Murphy Brewery celebrates 150 years of brewing from 1856 to 2006 going from strength to strength; the now legendary stout is sold in over 40 countries and recognised worldwide as superior stout. We hope James J. would be proud.

The Murphy Brewery celebrates 150 years of brewing from 1856 to 2006 going from strength to strength; the now legendary stout is sold in over 40 countries and recognised worldwide as superior stout. We hope James J. would be proud. -

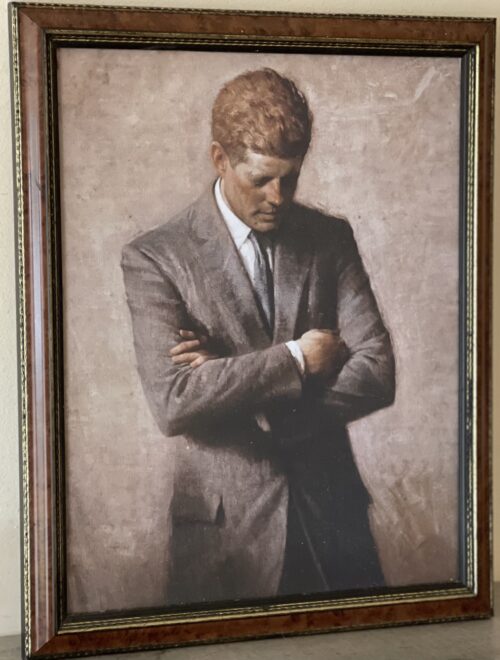

Superb portrait of President John F Kennedy in reflective pose . Such was the love and affection for President John F Kennedy in the country of his ancestors, that numerous Irish homes, businesses and pubs displayed photographs, portraits and other memorabilia relating to the Kennedy and Fitzgerald families. Origins :Co Kerry. Dimensions :39cm x 31cm. GlazedPresident Kennedy greeting Irish crowds while on a state visit to the country in 1963.

Superb portrait of President John F Kennedy in reflective pose . Such was the love and affection for President John F Kennedy in the country of his ancestors, that numerous Irish homes, businesses and pubs displayed photographs, portraits and other memorabilia relating to the Kennedy and Fitzgerald families. Origins :Co Kerry. Dimensions :39cm x 31cm. GlazedPresident Kennedy greeting Irish crowds while on a state visit to the country in 1963.55 years ago, President John F. Kennedy visited Ireland, his ancestral home, assuming that his family had mostly come from County Wexford, but new research shows us that JFK had links to many other Irish counties as well.

The President’s family tree, however, indicates that he has the most links to County Limerick, but also has connections to Limerick, Clare, Cork, and Fermanagh as research from Ancestry.com shed light onRussell James, a spokesperson for Ancestry Ireland, commented on how there is a great deal of discussion and research still ongoing about JFK’s roots to Ireland. “President John F. Kennedy’s family history has been a much-discussed topic over the years with his Irish roots being something that was extremely important to him. Traditionally JFK’s heritage has been closely linked with Wexford but we’re delighted to find records on Ancestry which show he had strong links to other counties across Ireland,” James said. “These findings will hopefully allow other counties across Ireland to further celebrate the life of the former American President, on the 55th anniversary of his visit to Ireland.” Limerick, as opposed to Wexford, had the most number of Kennedy’s great-grandparents, with three in total from his mother’s side: Mary Ann Fitzgerald, Michael Hannon, and Thomas Fitzgerald. The Fitzgeralds had come from a small town called Bruff in the eastern part of Limerick, but Hannon had come from Lough Gur. His great-grandfather, Thomas Fitzgerald, emigrated to the United States in the midst of the Irish famine of 1848 and eventually settled in Boston, Massachusetts. His Wexford connection is not as strong, given that only two of his great-grandparents came from the county. They were Patrick Kennedy of Dunganstown and Bridget Murphy from Owenduff. Patrick, when he arrived in the U.S in April 1849, was found to be a minor as shown on his American naturalization papers and had become a citizen three years later. He worked as a cooper in Boston until he died almost 10 years later in 1858. JFK had visited Dunganstown because his relatives had shared the Kennedy name there, but ultimately his roots lie deeper in Limerick through his mother’s side. The rest of his great-grandparents are from all over Ireland, with James Hickey from Newcastle-upon-Fergus, County Clare, Margaret M. Field from Rosscarbery, Cork, and Rosa Anna Cox from Tomregan in Fermanagh. Every one of them, though, had eventually emigrated and settled in Massachusetts. On Wednesday, June 26, 1963, Kennedy had arrived in Ireland, but on the second day, he made the journey to his ancestral home in Wexford, where he spent time with his relatives there and gave speeches in the surrounding area. While there, America’s first Irish Catholic President took a trip to Dunganstown, Wexford, where he met his extended family at the Kennedy homestead. It was there he made a toast to “all those Kennedys who went and all those Kennedys who stayed.” The homestead, now a visitor center, is where his great-grandfather lived and is still maintained by the current-day Kennedy family. This land itself was included in a land survey of Wexford in 1853, which shows that John Kennedy, JFK’s two-times great uncle, occupied the property described as having a ‘house, offices, and land’. -

Out of stock

32cm x 48cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.”

32cm x 48cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” -

24cm x 34cm Ennis Co Clare The Willie Clancy Summer School (Irish Scoil Samhraidh Willie Clancy) is Ireland's largest traditional music summer school held annually since 1973 in memory of the uilleann piper Willie Clancy. During the week, nearly a thousand students from every part of the world attend daily classes taught by experts in Irish music and dance. In addition, a full program of lectures, recitals, dances (céilithe) and exhibitions are run by the summer school. All events happen in the town of Milltown Malbay, in County Clare, on the west coast of Ireland, during the week beginning with the first Saturday of July. The weekly registration includes six classes, all lectures and recitals (except the Saturday concert) and reduced price admission to céilithe. Lectures, recitals, concert and céilithe are open to the public.

24cm x 34cm Ennis Co Clare The Willie Clancy Summer School (Irish Scoil Samhraidh Willie Clancy) is Ireland's largest traditional music summer school held annually since 1973 in memory of the uilleann piper Willie Clancy. During the week, nearly a thousand students from every part of the world attend daily classes taught by experts in Irish music and dance. In addition, a full program of lectures, recitals, dances (céilithe) and exhibitions are run by the summer school. All events happen in the town of Milltown Malbay, in County Clare, on the west coast of Ireland, during the week beginning with the first Saturday of July. The weekly registration includes six classes, all lectures and recitals (except the Saturday concert) and reduced price admission to céilithe. Lectures, recitals, concert and céilithe are open to the public.The school

Founded by a committee of local people, after the death of their friend and neighbour Willie Clancy, at a young age, in early 1973. The group included Paddy McMahon, Paddy Malone, Micheal O Friel, Junior Crehan, Martin Talty, Sean Reid, JC Talty and Jimmy Ward. These were later joined by Muiris Ó Rócháin (moved from Kerry 1971), Peadar O'Loughlin (Kilmaley) and after the first ten years of the school Eamonn McGivney and Harry Hughes. The school has a fine reputation as an event where Irish traditional music can be learned and practised by all. The school was founded with the idea that music could be learned outside of the strictures of competition or borders. Students are children or teenagers as well as adults. All are mixed within classes according to level of musicianship on a particular instrument. It is possible during the week to attend activities as different as reed making workshops for pipes, as well as concertinaclasses, for example. Classes are held in different venues: schools, hotels, and private houses. Depending on the student's wishes, it is possible to change teachers during the week. Teachers are chosen for their expertise and many are renowned exponents of Irish music and song.The craic

Craic agus ceol: "fun and music" in Irish, is a frequent description for the atmosphere. During the week, crowds come to Milltown Malbay solely for informal playing, or to listen to traditional Irish music in all kinds of venues - pubs, kitchens, and streets. This audience does not necessarily attend classes.O -

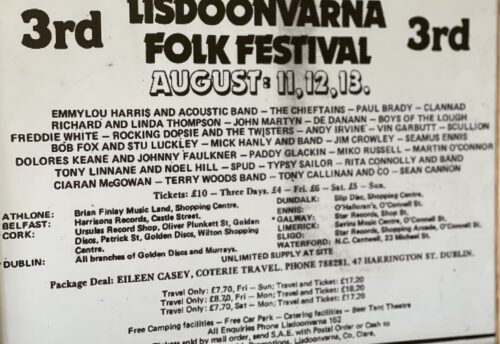

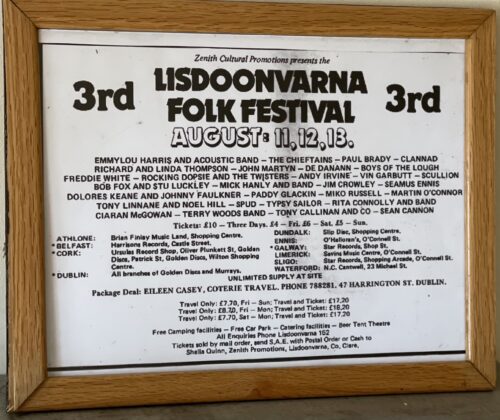

35cm x 45cm Ennis Co ClareOnce upon a time, the Lisdoonvarna Folk Festival was the largest and most famous outdoor music festival in Ireland. A total of 150 acts performed at the festival which took place each summer from 1978 to 1983. The festivals were the brainchild of local men, Paddy Doherty & Jim Shannon, with the first festival taking place in 1978, which proved to be a huge success. One Irish newspaper would go on to call these festivals the “Irish Woodstock” and the Irish equivalent to “Glastonbury”! A host of top Irish and international artists graced the stage during the 6 years the festival was held here. They included the likes of Jackson Browne, UB40, The Chieftains, Paul Brady, Loudon Wainwright III, Ralph McTell, The Fureys, De Dannan, Stocktons Wing, EmmyLou Harris, Van Morrison, Rory Gallagher, Panxty, Clannad, to name just a few, and of course the one and only Christy Moore, who wrote the world famous song about the festival, simply called “Lisdoonvarna”. The festivals enjoyed a hugely successful run until 1983 when two very unfortunate events sadly overshadowed the excellent performances on the stage and effectively ended the festival from being held in its original format.

35cm x 45cm Ennis Co ClareOnce upon a time, the Lisdoonvarna Folk Festival was the largest and most famous outdoor music festival in Ireland. A total of 150 acts performed at the festival which took place each summer from 1978 to 1983. The festivals were the brainchild of local men, Paddy Doherty & Jim Shannon, with the first festival taking place in 1978, which proved to be a huge success. One Irish newspaper would go on to call these festivals the “Irish Woodstock” and the Irish equivalent to “Glastonbury”! A host of top Irish and international artists graced the stage during the 6 years the festival was held here. They included the likes of Jackson Browne, UB40, The Chieftains, Paul Brady, Loudon Wainwright III, Ralph McTell, The Fureys, De Dannan, Stocktons Wing, EmmyLou Harris, Van Morrison, Rory Gallagher, Panxty, Clannad, to name just a few, and of course the one and only Christy Moore, who wrote the world famous song about the festival, simply called “Lisdoonvarna”. The festivals enjoyed a hugely successful run until 1983 when two very unfortunate events sadly overshadowed the excellent performances on the stage and effectively ended the festival from being held in its original format.

-

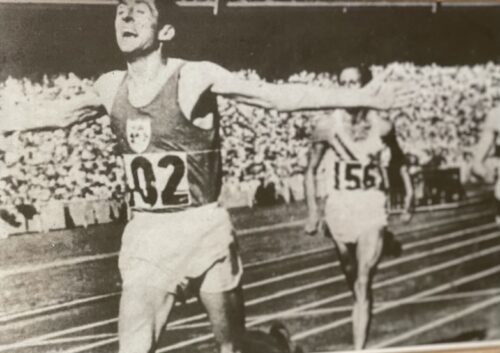

20cm x 35cm Limerick Ronald Michael Delany (born 6 March 1935), better known as Ron or Ronnie Delany, is an Irish former athlete, who specialised in middle-distance running. He won a gold medal in the 1500 metres event at the 1956 Summer Olympicsin Melbourne. He later earned a bronze medal in the 1500 metres event at the 1958 European Athletics Championships in Stockholm. Delany also competed at the 1954 European Athletics Championships in Bern and the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, though was less successful on these occasions. Retiring from competitive athletics in 1962, he has secured his status as Ireland's most recognisable Olympian as well as one of the greatest sportsmen and international ambassadors in his country's history.

20cm x 35cm Limerick Ronald Michael Delany (born 6 March 1935), better known as Ron or Ronnie Delany, is an Irish former athlete, who specialised in middle-distance running. He won a gold medal in the 1500 metres event at the 1956 Summer Olympicsin Melbourne. He later earned a bronze medal in the 1500 metres event at the 1958 European Athletics Championships in Stockholm. Delany also competed at the 1954 European Athletics Championships in Bern and the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, though was less successful on these occasions. Retiring from competitive athletics in 1962, he has secured his status as Ireland's most recognisable Olympian as well as one of the greatest sportsmen and international ambassadors in his country's history.Early life

Born in Arklow, County Wicklow, Delany moved with his family to Sandymount, Dublin 4 when he was six. Delany later went to Sandymount High School and then to Catholic University School. At Catholic University School Delany was first coached by Jack Sweeney (Maths Teacher) to whom he sent a telegram from Melbourne stating "We did it Jack" Delany in 2008 said about Sweeney "Other people would have seen my potential but he was the one who in effect helped me execute my potential" Delany studied commerce and finance at Villanova University in the United States. While there he was coached by the well-known track coach Jumbo Elliott.Career

Delany's first achievement of note was reaching the final of the 800 m at the 1954 European Athletics Championships in Bern. In 1956, he became the seventh runner to join the club of four-minute milers, but nonetheless struggled to make the Irish team for the 1956 Summer Olympics, held in Melbourne. Delany qualified for the Olympic 1500 m final, in which local runner John Landy was the big favourite. Delany kept close to Landy until the final lap, when he started a crushing final sprint, winning the race in a new Olympic record.Delany thereby became the first Irishman to win an Olympic gold medal in athletics since Bob Tisdall in 1932. The Irish people learned of its new champion at breakfast time.Delany was Ireland's last Olympic champion for 36 years, until Michael Carruth won the gold medal in boxing at the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona. Delany won the bronze medal in the 1500 m event at the 1958 European Athletics Championships. He went on to represent Ireland once again at the 1960 Summer Olympics held in Rome, this time in the 800 metres. He finished sixth in his quarter-final heat. Delany continued his running career in North America, winning four successive AAU titles in the mile, adding to his total of four Irish national titles, and three NCAA titles. He was next to unbeatable on indoor tracks over that period, which included a 40-race winning streak. He broke the World Indoor Mile Record on three occasions. In 1961 Delany won the gold medal in the World University games in Sofia, Bulgaria. He retired from competitive running in 1962.Retirement

After retiring from competitions Delany first worked in the United States for the Irish airline Aer Lingus. After that, for almost 20 years, he was Assistant Chief Executive of B&I Line, responsible for marketing and operations of the Irish ferry company based in Dublin. In 1998 he established his own company focused on marketing and sports consultancy.Honours

In 2006, Delany was granted the Freedom of the City of Dublin. He was also conferred with an honorary Doctor of Laws Degree by University College Dublin in 2006. In 2019, a housing scheme in Arklow, where Delany was born, was named Delany Park in his honour. He attended the opening in person. Similarly, two streets in Strabane in Northern Ireland were named Delaney Crescent and Olympic Drive in the 1950s in his honour – however, Delany was not aware of these until it was pointed out that his surname had been spelt wrongly -

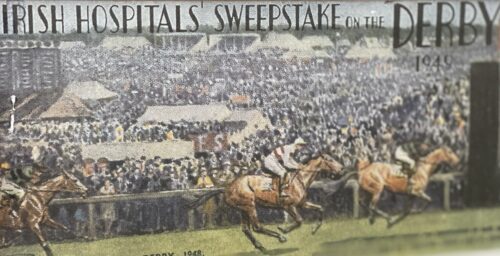

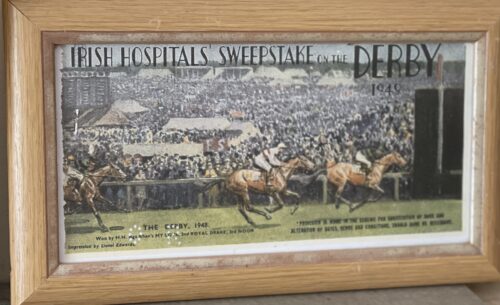

Vintage ticket for the Irish Hospital Sweepstakes 1949 Epsom Derby Dublin 35cm x 20cm The Irish Hospital Sweepstake was a lottery established in the Irish Free State in 1930 as the Irish Free State Hospitals' Sweepstake to finance hospitals. It is generally referred to as the Irish Sweepstake, frequently abbreviated to Irish Sweeps or Irish Sweep. The Public Charitable Hospitals (Temporary Provisions) Act, 1930 was the act that established the lottery; as this act expired in 1934, in accordance with its terms, the Public Hospitals Acts were the legislative basis for the scheme thereafter. The main organisers were Richard Duggan, Captain Spencer Freeman and Joe McGrath. Duggan was a well known Dublin bookmaker who had organised a number of sweepstakes in the decade prior to setting up the Hospitals' Sweepstake. Captain Freeman was a Welsh-born engineer and former captain in the British Army. After the Constitution of Ireland was enacted in 1937, the name Irish Hospitals' Sweepstake was adopted. The sweepstake was established because there was a need for investment in hospitals and medical services and the public finances were unable to meet this expense at the time. As the people of Ireland were unable to raise sufficient funds, because of the low population, a significant amount of the funds were raised in the United Kingdom and United States, often among the emigrant Irish. Potentially winning tickets were drawn from rotating drums, usually by nurses in uniform. Each such ticket was assigned to a horse expected to run in one of several horse races, including the Cambridgeshire Handicap, Derby and Grand National. Tickets that drew the favourite horses thus stood a higher likelihood of winning and a series of winning horses had to be chosen on the accumulator system, allowing for enormous prizes. The original sweepstake draws were held at The Mansion House, Dublin on 19 May 1939 under the supervision of the Chief Commissioner of Police, and were moved to the more permanent fixture at the Royal Dublin Society (RDS) in Ballsbridge later in 1940. The Adelaide Hospital in Dublin was the only hospital at the time not to accept money from the Hospitals Trust, as the governors disapproved of sweepstakes. From the 1960s onwards, revenues declined. The offices were moved to Lotamore House in Cork. Although giving the appearance of a public charitable lottery, with nurses featured prominently in the advertising and drawings, the Sweepstake was in fact a private for-profit lottery company, and the owners were paid substantial dividends from the profits. Fortune Magazine described it as "a private company run for profit and its handful of stockholders have used their earnings from the sweepstakes to build a group of industrial enterprises that loom quite large in the modest Irish economy. Waterford Glass, Irish Glass Bottle Company and many other new Irish companies were financed by money from this enterprise and up to 5,000 people were given jobs."[3] By his death in 1966, Joe McGrath had interests in the racing industry, and held the Renault dealership for Ireland besides large financial and property assets. He was known throughout Ireland for his tough business attitude but also by his generous spirit.At that time, Ireland was still one of the poorer countries in Europe; he believed in investment in Ireland. His home, Cabinteely House, was donated to the state in 1986. The house and the surrounding park are now in the ownership of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council who have invested in restoring and maintaining the house and grounds as a public park. In 1986, the Irish government created a new public lottery, and the company failed to secure the new contract to manage it. The final sweepstake was held in January 1986 and the company was unsuccessful for a licence bid for the Irish National Lottery, which was won by An Post later that year. The company went into voluntary liquidation in March 1987. The majority of workers did not have a pension scheme but the sweepstake had fed many families during lean times and was regarded as a safe job.The Public Hospitals (Amendment) Act, 1990 was enacted for the orderly winding up of the scheme which had by then almost £500,000 in unclaimed prizes and accrued interest. A collection of advertising material relating to the Irish Hospitals' Sweepstakes is among the Special Collections of National Irish Visual Arts Library. At the time of the Sweepstake's inception, lotteries were generally illegal in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. In the absence of other readily available lotteries, the Irish Sweeps became popular. Even though tickets were illegal outside Ireland, millions were sold in the US and Great Britain. How many of these tickets failed to make it back for the drawing is unknown. The United States Customs Service alone confiscated and destroyed several million counterfoils from shipments being returned to Ireland. In the UK, the sweepstakes caused some strain in Anglo-Irish relations, and the Betting and Lotteries Act 1934 was passed by the parliament of the UK to prevent export and import of lottery related materials. The United States Congress had outlawed the use of the US Postal Service for lottery purposes in 1890. A thriving black market sprang up for tickets in both jurisdictions. From the 1950s onwards, as the American, British and Canadian governments relaxed their attitudes towards this form of gambling, and went into the lottery business themselves, the Irish Sweeps, never legal in the United States,declined in popularity. Origins: Co Galway Dimensions :39cm x 31cm

Vintage ticket for the Irish Hospital Sweepstakes 1949 Epsom Derby Dublin 35cm x 20cm The Irish Hospital Sweepstake was a lottery established in the Irish Free State in 1930 as the Irish Free State Hospitals' Sweepstake to finance hospitals. It is generally referred to as the Irish Sweepstake, frequently abbreviated to Irish Sweeps or Irish Sweep. The Public Charitable Hospitals (Temporary Provisions) Act, 1930 was the act that established the lottery; as this act expired in 1934, in accordance with its terms, the Public Hospitals Acts were the legislative basis for the scheme thereafter. The main organisers were Richard Duggan, Captain Spencer Freeman and Joe McGrath. Duggan was a well known Dublin bookmaker who had organised a number of sweepstakes in the decade prior to setting up the Hospitals' Sweepstake. Captain Freeman was a Welsh-born engineer and former captain in the British Army. After the Constitution of Ireland was enacted in 1937, the name Irish Hospitals' Sweepstake was adopted. The sweepstake was established because there was a need for investment in hospitals and medical services and the public finances were unable to meet this expense at the time. As the people of Ireland were unable to raise sufficient funds, because of the low population, a significant amount of the funds were raised in the United Kingdom and United States, often among the emigrant Irish. Potentially winning tickets were drawn from rotating drums, usually by nurses in uniform. Each such ticket was assigned to a horse expected to run in one of several horse races, including the Cambridgeshire Handicap, Derby and Grand National. Tickets that drew the favourite horses thus stood a higher likelihood of winning and a series of winning horses had to be chosen on the accumulator system, allowing for enormous prizes. The original sweepstake draws were held at The Mansion House, Dublin on 19 May 1939 under the supervision of the Chief Commissioner of Police, and were moved to the more permanent fixture at the Royal Dublin Society (RDS) in Ballsbridge later in 1940. The Adelaide Hospital in Dublin was the only hospital at the time not to accept money from the Hospitals Trust, as the governors disapproved of sweepstakes. From the 1960s onwards, revenues declined. The offices were moved to Lotamore House in Cork. Although giving the appearance of a public charitable lottery, with nurses featured prominently in the advertising and drawings, the Sweepstake was in fact a private for-profit lottery company, and the owners were paid substantial dividends from the profits. Fortune Magazine described it as "a private company run for profit and its handful of stockholders have used their earnings from the sweepstakes to build a group of industrial enterprises that loom quite large in the modest Irish economy. Waterford Glass, Irish Glass Bottle Company and many other new Irish companies were financed by money from this enterprise and up to 5,000 people were given jobs."[3] By his death in 1966, Joe McGrath had interests in the racing industry, and held the Renault dealership for Ireland besides large financial and property assets. He was known throughout Ireland for his tough business attitude but also by his generous spirit.At that time, Ireland was still one of the poorer countries in Europe; he believed in investment in Ireland. His home, Cabinteely House, was donated to the state in 1986. The house and the surrounding park are now in the ownership of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council who have invested in restoring and maintaining the house and grounds as a public park. In 1986, the Irish government created a new public lottery, and the company failed to secure the new contract to manage it. The final sweepstake was held in January 1986 and the company was unsuccessful for a licence bid for the Irish National Lottery, which was won by An Post later that year. The company went into voluntary liquidation in March 1987. The majority of workers did not have a pension scheme but the sweepstake had fed many families during lean times and was regarded as a safe job.The Public Hospitals (Amendment) Act, 1990 was enacted for the orderly winding up of the scheme which had by then almost £500,000 in unclaimed prizes and accrued interest. A collection of advertising material relating to the Irish Hospitals' Sweepstakes is among the Special Collections of National Irish Visual Arts Library. At the time of the Sweepstake's inception, lotteries were generally illegal in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. In the absence of other readily available lotteries, the Irish Sweeps became popular. Even though tickets were illegal outside Ireland, millions were sold in the US and Great Britain. How many of these tickets failed to make it back for the drawing is unknown. The United States Customs Service alone confiscated and destroyed several million counterfoils from shipments being returned to Ireland. In the UK, the sweepstakes caused some strain in Anglo-Irish relations, and the Betting and Lotteries Act 1934 was passed by the parliament of the UK to prevent export and import of lottery related materials. The United States Congress had outlawed the use of the US Postal Service for lottery purposes in 1890. A thriving black market sprang up for tickets in both jurisdictions. From the 1950s onwards, as the American, British and Canadian governments relaxed their attitudes towards this form of gambling, and went into the lottery business themselves, the Irish Sweeps, never legal in the United States,declined in popularity. Origins: Co Galway Dimensions :39cm x 31cmThe Irish Hospitals Sweepstake was established because there was a need for investment in hospitals and medical services and the public finances were unable to meet this expense at the time. As the people of Ireland were unable to raise sufficient funds, because of the low population, a significant amount of the funds were raised in the United Kingdom and United States, often among the emigrant Irish. Potentially winning tickets were drawn from rotating drums, usually by nurses in uniform. Each such ticket was assigned to a horse expected to run in one of several horse races, including the Cambridgeshire Handicap, Derby and Grand National. Tickets that drew the favourite horses thus stood a higher likelihood of winning and a series of winning horses had to be chosen on the accumulator system, allowing for enormous prizes.

The original sweepstake draws were held at The Mansion House, Dublin on 19 May 1939 under the supervision of the Chief Commissioner of Police, and were moved to the more permanent fixture at the Royal Dublin Society (RDS) in Ballsbridge later in 1940. The Adelaide Hospital in Dublin was the only hospital at the time not to accept money from the Hospitals Trust, as the governors disapproved of sweepstakes. From the 1960s onwards, revenues declined. The offices were moved to Lotamore House in Cork. Although giving the appearance of a public charitable lottery, with nurses featured prominently in the advertising and drawings, the Sweepstake was in fact a private for-profit lottery company, and the owners were paid substantial dividends from the profits. Fortune Magazine described it as "a private company run for profit and its handful of stockholders have used their earnings from the sweepstakes to build a group of industrial enterprises that loom quite large in the modest Irish economy. Waterford Glass, Irish Glass Bottle Company and many other new Irish companies were financed by money from this enterprise and up to 5,000 people were given jobs."By his death in 1966, Joe McGrath had interests in the racing industry, and held the Renault dealership for Ireland besides large financial and property assets. He was known throughout Ireland for his tough business attitude but also by his generous spirit. At that time, Ireland was still one of the poorer countries in Europe; he believed in investment in Ireland. His home, Cabinteely House, was donated to the state in 1986. The house and the surrounding park are now in the ownership of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council who have invested in restoring and maintaining the house and grounds as a public park. In 1986, the Irish government created a new public lottery, and the company failed to secure the new contract to manage it. The final sweepstake was held in January 1986 and the company was unsuccessful for a licence bid for the Irish National Lottery, which was won by An Post later that year. The company went into voluntary liquidation in March 1987. The majority of workers did not have a pension scheme but the sweepstake had fed many families during lean times and was regarded as a safe job.The Public Hospitals (Amendment) Act, 1990 was enacted for the orderly winding up of the scheme,which had by then almost £500,000 in unclaimed prizes and accrued interest. A collection of advertising material relating to the Irish Hospitals' Sweepstakes is among the Special Collections of National Irish Visual Arts Library.In the United Kingdom and North America[edit]

At the time of the Sweepstake's inception, lotteries were generally illegal in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. In the absence of other readily available lotteries, the Irish Sweeps became popular. Even though tickets were illegal outside Ireland, millions were sold in the US and Great Britain. How many of these tickets failed to make it back for the drawing is unknown. The United States Customs Service alone confiscated and destroyed several million counterfoils from shipments being returned to Ireland. In the UK, the sweepstakes caused some strain in Anglo-Irish relations, and the Betting and Lotteries Act 1934 was passed by the parliament of the UK to prevent export and import of lottery related materials.[6][7] The United States Congress had outlawed the use of the US Postal Service for lottery purposes in 1890. A thriving black market sprang up for tickets in both jurisdictions. From the 1950s onwards, as the American, British and Canadian governments relaxed their attitudes towards this form of gambling, and went into the lottery business themselves, the Irish Sweeps, never legal in the United States,[8]:227 declined in popularity. -

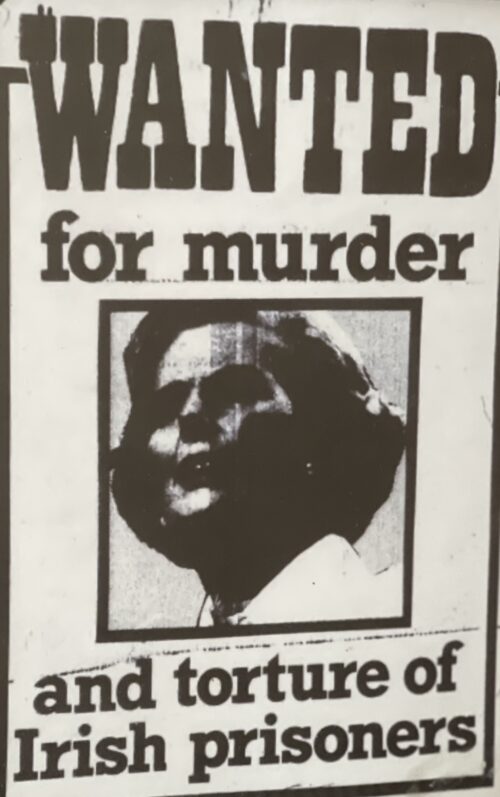

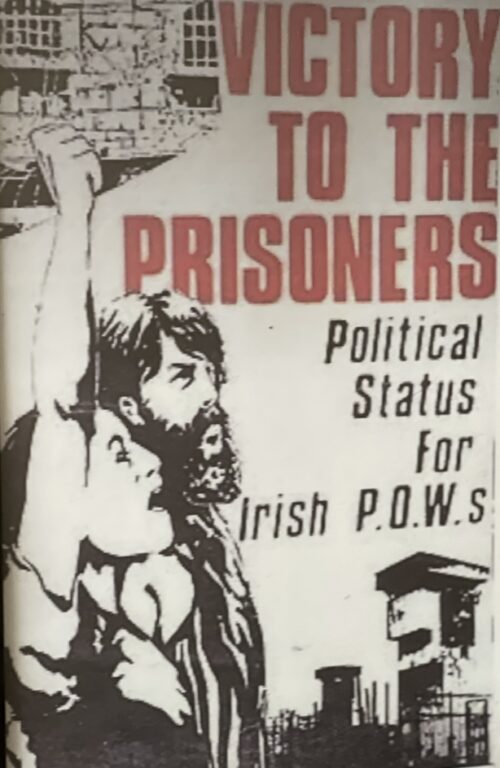

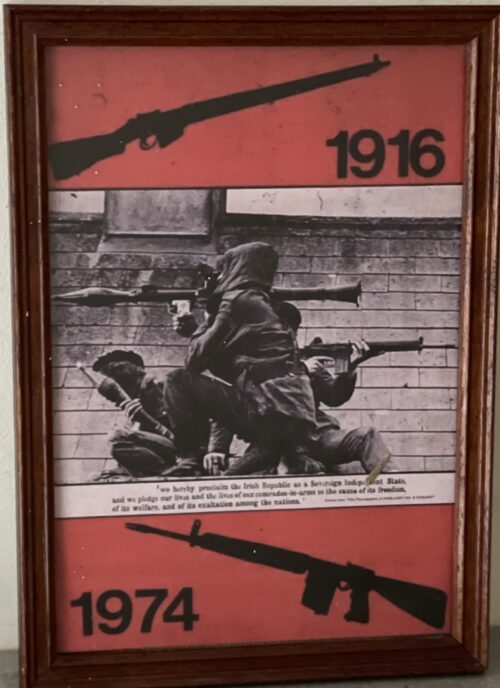

25cm x 30cm Glasgow

25cm x 30cm GlasgowThe Troubles, also called Northern Ireland conflict, violent sectarian conflict from about 1968 to 1998 in Northern Irelandbetween the overwhelmingly Protestantunionists (loyalists), who desired the province to remain part of the United Kingdom, and the overwhelmingly Roman Catholic nationalists (republicans), who wanted Northern Ireland to become part of the republic of Ireland. The other major players in the conflict were the British army, Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR; from 1992 called the Royal Irish Regiment), and their avowed purpose was to play a peacekeeping role, most prominently between the nationalist Irish Republican Army(IRA), which viewed the conflict as a guerrilla war for national independence, and the unionist paramilitary forces, which characterized the IRA’s aggression as terrorism. Marked by street fighting, sensational bombings, sniper attacks, roadblocks, and internment without trial, the confrontation had the characteristics of a civil war, notwithstanding its textbook categorization as a “low-intensity conflict.” Some 3,600 people were killed and more than 30,000 more were wounded before a peaceful solution, which involved the governments of both the United Kingdom and Ireland, was effectively reached in 1998, leading to a power-sharing arrangement in the Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont.

Deep origins

The story of the Troubles is inextricably entwined with the history of Ireland as whole and, as such, can be seen as stemming from the first British incursion on the island, the Anglo-Norman invasion of the late 12th century, which left a wave of settlers whose descendants became known as the “Old English.” Thereafter, for nearly eight centuries, England and then Great Britain as a whole would dominate affairs in Ireland. Colonizing British landlords widely displaced Irish landholders. The most successful of these “plantations” began taking hold in the early 17th century in Ulster, the northernmost of Ireland’s four traditional provinces, previously a centre of rebellion, where the planters included English and Scottish tenants as well as British landlords. Because of the plantation of Ulster, as Irish history unfolded—with the struggle for the emancipation of the island’s Catholic majority under the supremacy of the Protestant ascendancy, along with the Irish nationalist pursuit of Home Rule and then independence after the island’s formal union with Great Britain in 1801—Ulster developed as a region where the Protestant settlers outnumbered the indigenousIrish. Unlike earlier English settlers, most of the 17th-century English and Scottish settlers and their descendants did not assimilate with the Irish. Instead, they held on tightly to British identity and remained steadfastly loyal to the British crown.

The formation of Northern Ireland, Catholic grievances, and the leadership of Terence O’Neill

Of the nine modern counties that constituted Ulster in the early 20th century, four—Antrim, Down, Armagh, and Londonderry (Derry)—had significant Protestant loyalist majorities; two—Fermanagh and Tyrone—had small Catholic nationalist majorities; and three—Donegal, Cavan, and Monaghan—had significant Catholic nationalist majorities. In 1920, during the Irish War of Independence (1919–21), the British Parliament, responding largely to the wishes of Ulster loyalists, enacted the Government of Ireland Act , which divided the island into two self-governing areas with devolved Home Rule-like powers. What would come to be known as Northern Ireland was formed by Ulster’s four majority loyalist counties along with Fermanagh and Tyrone. Donegal, Cavan, and Monaghan were combined with the island’s remaining 23 counties to form southern Ireland. The Anglo-Irish Treaty that ended the War of Independence then created the Irish Free State in the south, giving it dominion status within the British Empire. It also allowed Northern Ireland the option of remaining outside of the Free State, which it unsurprisingly chose to do.

Thus, in 1922 Northern Ireland began functioning as a self-governing region of the United Kingdom. Two-thirds of its population (about one million people) was Protestant and about one-third (roughly 500,000 people) was Catholic. Well before partition, Northern Ireland, particularly Belfast, had attracted economic migrants from elsewhere in Ireland seeking employment in its flourishing linen-making and shipbuilding industries. The best jobs had gone to Protestants, but the humming local economy still provided work for Catholics. Over and above the long-standing dominance of Northern Ireland politics that resulted for the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) by virtue of the Protestants’ sheer numerical advantage, loyalist control of local politics was ensured by the gerrymandering of electoral districts that concentrated and minimized Catholic representation. Moreover, by restricting the franchise to ratepayers (the taxpaying heads of households) and their spouses, representation was further limited for Catholic households, which tended to be larger (and more likely to include unemployed adult children) than their Protestant counterparts. Those who paid rates for more than one residence (more likely to be Protestants) were granted an additional vote for each ward in which they held property (up to six votes). Catholics argued that they were discriminated against when it came to the allocation of public housing, appointments to public service jobs, and government investment in neighbourhoods. They were also more likely to be the subjects of police harassment by the almost exclusively Protestant RUC and Ulster Special Constabulary (B Specials).

The divide between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland had little to do with theological differences but instead was grounded in culture and politics. Neither Irish history nor the Irish language was taught in schools in Northern Ireland, it was illegal to fly the flag of the Irish republic, and from 1956 to 1974 Sinn Féin, the party of Irish republicanism, also was banned in Northern Ireland. Catholics by and large identified as Irish and sought the incorporation of Northern Ireland into the Irish state. The great bulk of Protestants saw themselves as British and feared that they would lose their culture and privilege if Northern Ireland were subsumed by the republic. They expressed their partisan solidarity through involvement with Protestant unionist fraternal organizations such as the Orange Order, which found its inspiration in the victory of King William III (William of Orange) at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 over his deposed Catholic predecessor, James II, whose siege of the Protestant community of Londonderry had earlier been broken by William. Despite these tensions, for 40 or so years after partition the status of unionist-dominated Northern Ireland was relatively stable.

IRA graffiti “IRA” spray-painted on a container, Derry (Londonderry), Northern Ireland.© Attila Jandi/Dreamstime.comRecognizing that any attempt to reinvigorate Northern Ireland’s declining industrial economy in the early 1960s would also need to address the province’s percolatingpolitical and social tensions, the newly elected prime minister of Northern Ireland, Terence O’Neill, not only reached out to the nationalist community but also, in early 1965, exchanged visits with Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Seán Lemass—a radical step, given that the republic’s constitution included an assertion of sovereignty over the whole island. Nevertheless, O’Neill’s efforts were seen as inadequate by nationalists and as too conciliatory by loyalists, including the Rev. Ian Paisley, who became one of the most vehement and influential representatives of unionist reaction.

Civil rights activism, the Battle of Bogside, and the arrival of the British army

Contrary to the policies of UUP governments that disadvantaged Catholics, the Education Act that the Northern Ireland Parliament passed into law in 1947 increased educational opportunities for all citizens of the province. As a result, the generation of well-educated Catholics who came of age in the 1960s had new expectations for more equitable treatment. At a time when political activism was on the rise in Europe—from the events of May 1968 in France to the Prague Spring—and when the American civil rights movement was making great strides, Catholic activists in Northern Ireland such as John Humeand Bernadette Devlin came together to form civil rightsgroups such as the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA).

Although more than one violently disrupted political march has been pointed to as the starting point of the Troubles, it can be argued that the catalyzing event occurred on October 5, 1968, in Derry, where a march had been organized by the NICRA to protest discrimination and gerrymandering. The march was banned when unionists announced that they would be staging a counterdemonstration, but the NICRA decided to carry out their protest anyway. Rioting then erupted after the RUC violently suppressed the marchers with batons and a water cannon.

Similarly inflammatory were the events surrounding a march held by loyalists in Londonderry on August 12, 1969. Two days of rioting that became known as the Battle of Bogside (after the Catholic area in which the confrontation occurred) stemmed from the escalating clash between nationalists and the RUC, which was acting as a buffer between loyalist marchers and Catholic residents of the area. Rioting in support of the nationalists then erupted in Belfast and elsewhere, and the British army was dispatched to restore calm. Thereafter, violent confrontation only escalated, and the Troubles (a name that neither characterized the nature of the conflict nor assigned blame for it to one side or the other) had clearly begun.

The emergence of the Provisional IRA and the loyalist paramilitaries