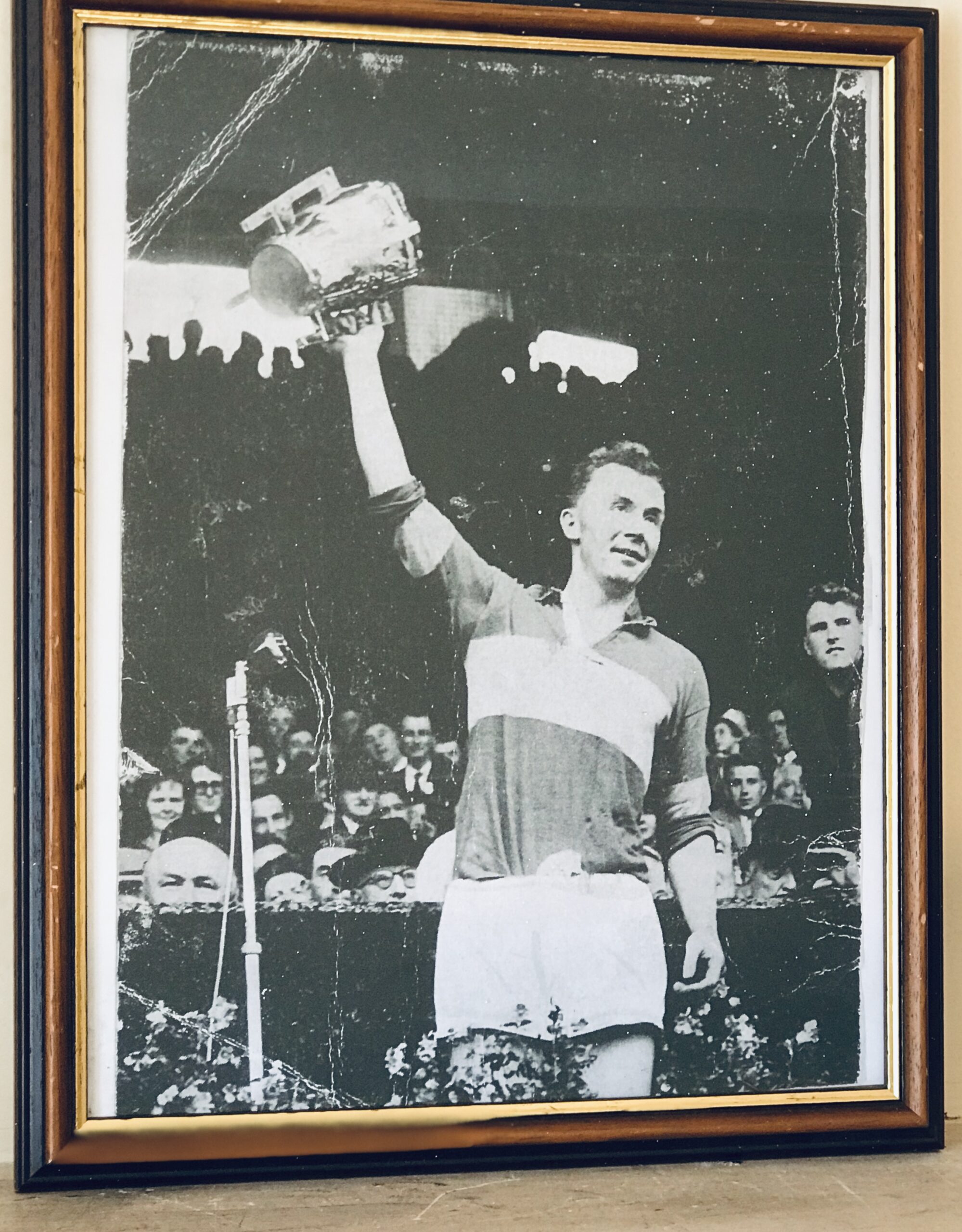

Beautiful B&W image of legendary Tipperary captain Tony Wall lifting the Liam McCarthy after winning the 1958 All Ireland Hurling Final.

Thurles Co Tipperary 45cm x 35cm

Tony Wall was in charge of the last Tipperary championship team that took on Clare in Ennis. Thirty-three years later, he looks back on a famous career, considering all that could have gone wrong as well as all that went so well. A holder of five All-Ireland medals, Wall was one of the game’s finest ever centre-backs and the author of a still fresh book, Hurling (1965). If he wrote a sequel today, he’d advise a couple of small tweaks to the modern game.

“We have no electricity,” Tony Wall says, greeting me at the door.

“We didn’t meet until after the 1958 All-Ireland final,” Wall relates. “So Betty didn’t start going to any of the matches until 1959.” He expands: “She was from a totally non GAA background in Dublin. I was this savage from down the country, bringing her away from civilisation. I was even bringing her to hurling matches…”

Mrs Wall beams. She found quite a first championship day out. Tipperary, the reigning All-Ireland champions, had Waterford in a Munster semi-final on July 12, 1959. A gale entered the Cork Athletic Grounds and stayed there. Strong wind means a tough decision. Tipperary won the toss and here was that decision.

“I was captain, same as the year before,” Wall begins. “I decided on going against the wind. I felt I had no choice because of previous experience.”

Tough decisions mean strong opinions. “I was there with Tony’s mother,” Mrs Wall remembers. “She didn’t agree with the decision to go against the wind. I said to her not to be putting the mí ádh on the team. But maybe…”

Behind this decision in 1959 lay another match in 1956. “We met Wexford in that league final,” Wall explains.”We were up 15 points at half-time, having played with a strong wind. Then Wexford came back out in a frenzy and scored three or four goals in less than 10 minutes. We ended up losing by four points, on a famous day.”

Wall’s call was dictated by this reversal. “Waterford just blitzed us. It was the greatest display of free-flowing hurling I ever saw. They ran through us lightening. Terry Moloney was the goalie and he couldn’t be faulted for any of the balls that passed him.”

Behind 8-2 to 0-0 at half-time, Tipperary played only for pride in the second half. They were out. The contrast was stark with the previous season when Tony Wall captained Tipperary to All-Ireland glory, won Man of the Match in the final, and was made Caltex Hurler of the Year.

“It was only because Tipperary were beaten that we could get married,” Wall reflects. “I had just been posted down to Limerick. We headed off nearly the next day, everything packed in the back of the Volkswagen, and eventually got a house there.

“Everyone really welcomed Betty into the hurling, both with the county and with the club. I think they knew our situation, that we were a bit cut off. I was the first of the younger lads to get married.”

Mrs Wall adds: “Everyone was so friendly, the whole circle. We will be 60 years married in August. If we get there…”

“I was there as an experienced player,” Wall begins. “Paddy Leahy as supremo in chief. Jim said to us: ‘So and so has a woman in his room. What are we going to do?’ Paddy was great in these situations, cool out. He just said: ‘Look, we’ll all say a decade of the Rosary, and hope for the best.’ That was that.”

The other side of romance became a factor in 1962. As Wall recounts: “Our goalkeeper, Dónal O’Brien, got married the Saturday before the All-Ireland final.”

“Eight days before it?” I say, slow on uptake.

“No, one day,” he replies. “Dónal got married on the day before the final.” He smiles at my amazement: “There weren’t that many of the players there. Myself and Betty did go. None of us were drinking, of course. But still… But we thought nothing of it at the time.”

He smiles again: “Dónal was a terrific goalkeeper. He has a remarkable record of never being beaten in a championship match while he hurled with Tipperary, during 1961 and ’62. Got married on the Saturday, won the All-Ireland on the Sunday, went to America for good on the Monday… That was it.”

A knock at the door breaks the laughter. The man of the house goes to see. The Walls’ next door neighbour has come to check: Would they like some tea?

“Our neighbours have gas for cooking,” Mrs Wall says. “So they’re not too badly fixed today.”

She starts to recall the shape of her childhood, central Dublin in the 1930s and ’40s: “There wasn’t that much electricity, back then, even in Dublin. It was mostly gaslight, which was a lovely soft light. Fade Street was gorgeous in the evening, and really quiet at the weekends, when all the traffic had gone. My father, who’d fought in the First World War, came back and eventually managed to establish a jewellery case-making business there.

“I kept one of those old lamps, and our daughter Sharon saw it and said: ‘That’s lovely. Could I have it?’ And of course we said yes, even though we could have done with it a few times afterwards. But of course we said nothing…”

Tony Wall comes back, arrangements made. There is no complacency in this man at all. Right to this day, the elderly man is fulfilment of a talented determined youth. He could sit back, cushioned by five Celtic Crosses, six NHL titles, five Railway Cups, a Minor All-Ireland in 1952 (which he captained), 11 Tipperary senior titles between 1952 and 1965. Those gongs would deafen anyone else’s modesty.

Tony Wall proved not just one of Tipperary’s greatest but one of hurling’s greatest. At centre-back, he was that good. But this man looks back on how it could all have been different. He takes me to the Cadet Mess in The Curragh during early summer of 1953. He was reading the Sunday Independent, when he noticed John D Hickey reporting that a rule change meant Tony Wall would now be eligible for Thurles Sarsfields.

“Previously you had to be living in the parish to hurl with that club. I could have ended up hurling with Newbridge or somewhere else in Kildare. But the rule change meant you could declare for the club with which you’d hurled the previous season.”

Wall jumped up, got his gear, and thumbed home to play a club match. “Then I was there with Sarsfields for 50 years!”

There was a more serious consideration: “I hurled Harty Cup with Lauri McDonnell. He is a very talented hurler, but kind of got lost in Dublin. He was a year older, and fell the other side of that rule change.

“Right to the end, Lauri always wondered if he could have been a contender. I needed to be hurling club in Tipp. It wasn’t all plain sailing with Tipp in the early days, and I needed to keep my name there. I was shunted into the forwards. Without club hurling at home, I could have got lost too.”

Tony Wall has thought as deeply about hurling as anyone. The present so often patronises the past. Wall is a courteous rebuke. These switches in position, however difficult at the time, did become a resource. 1965 saw the publication of Hurling, a book still brimming with commonsense, insight and wisdom. Should this book not have found a new edition, rewritten in light of later developments?

He has retained an immersion in the game. Again, Tony Wall’s mordant side emerges: “Your name goes. You get forgotten about. And rightly so, really.”

Tony Wall is Thurles, one of hurling’s sources from the start. He states: “I was really honoured to launch Liam O Donnchú’s book. He is a brilliant historian.”

But Walls’ take on history is partly mordant: “There were old fellas, like myself now, walking around the town.”

Jim Stapleton of Thurles captained Tipperary to victory over Galway in 1887’s senior final, the inaugural contest – 71 seasons later, Tony Wall of Thurles Sarsfields repeated the feat. Mostly made of the same wood, the Tipperary wheel turned and turned.”I remember, as a young fella, seeing [Jim] Stapleton around the town. He would be mentioned. A big tall stately man. But as a child you’re not tuned into these things.”

The past comes later. Yet he did grow up with a keen sense of old glories. “There were plenty of older players around,” he continues. “Paddy Brolan was there. Died in the mid-1950s. I knew Tom Semple’s children. And Tommy Butler, who kept goal in 1937, was the key influence in changing me from a left hand on top grip to right hand on top.”

The sensibility that authored so incisive a monograph on the most beautiful game has not disappeared. The analytical mind is undimmed. Wall urges action in two main areas of the contemporary game: the steps rule and the nature of frees.

“I think the current hurlers are incredibly skilful,” he stresses. “The ball is travelling so far and so fast that it’s amazing the skill they have in controlling, sending it 70 yards with just a flick. There are lads scoring points from 100 yards for fun. But one of the things I really don’t like in the current game is this running with the ball in the hand. What a fella is doing that, what can an opponent do to stop him? There’s feck all he can do.”

He continues: “In our time, it was three steps with the ball. You got pulled for this rule. Sometime in the 1970s, for whatever reason, it was increased to four steps which is actually five, six, seven, eight steps… When it was three steps, you’d no need to foul, because you’d get in a tackle as the man in possession went to play the ball.”

Would he return to a three-step rule? “Yes, definitely. I’d love to see it go back to three steps, so that you have to play the ball quicker. That would go a long way towards eliminating frees and those scrummages.

“Everyone wants to pick up the ball. As soon as they pick it, they charge. Put down the head and charge. I know ‘charging’ is still in the rulebook. But referees seem to have forgotten it.”

Wall offers an intriguing contrast between codes: “When the ball is in hand, it’s more like football. What can you do when an opponent has the ball in his hand? With other lads running off his shoulder? That’s a new concept, and hurling is still figuring it out.

“If the ball is always loose… That’s the beauty of soccer. The ball is never hidden from view. It’s always in play, in soccer. There is no great skill in running with the ball. It should be anathema to a hurler. Or should be, to a stickman.”

This observer discerns the glimmer of a different future in compromise shinty games: “On these occasions, the Irish lads cannot take the ball in their hand. Look at the skill they then find… They’re back to being hurlers. Not taking the ball to hand eliminates the pulling down.”

The other bugbear is inappropriately weighted penalties: “Is a pointed free enough at times? I think, for a yellow card issue, that kind of foul, there should be a free for two points. If you have a ‘pulling down’ foul, a bit like the black card in football, you could go this way. And it would eliminate putting off lads, except for vicious fouls.

Wall elaborates: “If this kind of foul is committed by a forward in his own full-forward line, the ball should be brought out to a scoreable distance.

“What does this ‘letting it flow’ mean? All this approach means is that you don’t pull clear frees. A two-point penalty would solve a lot of it. If a referee at present actually refereed a game of hurling properly, that referee wouldn’t get any more games.”

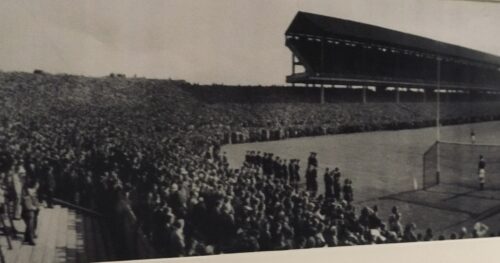

For better or worse, this season’s hurling will continue under the current rules. Tipperary travel to Ennis tomorrow, taking on Clare. Cusack Park hosts a championship match between the two counties for the first time since 1986. The man in charge of Tipperary 33 years ago, coach and trainer? One Tony Wall.

The county experienced many lacerating championship days between 1972 and 1986. No one felt ‘The Famine’ overdid the matter as description. 1986’s impact felt like the nadir. Injury difficulties did not help. A collapsed lung suffered while kicking football meant Nicky English’s absence.

Even so, Tipperary led by seven points at half-time. Although the gap widened to nine points after the break, calamity was about to hatch. Clare outscored the visitors by 2-4 to 0-1 over the closing stages. Full-time: 1-11 to 2-10. Tipperary were gone, again. That puckish side:”Do we have to talk about 1986?”

Time has not entirely cancelled exasperation: “I was parachuted in out the blue. It was the worst decision I ever made. I should never have taken the job. Mrs Wall says: “I remember that time. All the stress and difficulties…”

Her husband elaborates: “I was too far away from it. I’d been years not involved with teams, nearly 20 years out of it. I didn’t know the Tipp scene at all. Anyway, I should have known better. A delegation landed in here to me. I suppose you could say they appealed to my Tipperary patriotism. You could also say they were desperate…

“I went down [to Thurles] the Saturday night before the Clare game, to finalise the team. There seemed to be about 25 people on the selection committee… I don’t know what they were all doing in the room. AnywayI should have had more sense.”

Natural merriment survives even these memories: “If we’d beaten Clare, after getting that big lead, and won the Munster final against Cork, God knows what would have happened… I could have been there for all time!”

Another throaty laugh: “No, we were beaten, and I was out, and I was happy as Larry to be out.

“But maybe it wasn’t all for nothing. I wrote a report afterwards, urging that a sole manager be appointed. I don’t know whether the county board actually read it, but they did appoint [Michael] ‘Babs’ Keating as sole manager, and Tipp got back to winning Munsters and All-Irelands.”

Thoughts of Tipperary and Clare tomorrow delivers a natural break. I turn off my recorder. Wall feels this day will be a different test for the Tipperary backs: “If they go well against the Clare forwards, 2019 could be a long campaign.”

He admires Éamon O’Shea’s renewed input: “I don’t know the inside story but he seems to be a tremendous coach and tactician. He came on as a sub in 1986, but I don’t ever remember us ever having a proper conversation.”

Then this man, not for the first time, surprises me. “Could I finish off with a poem?” he asks. “Of course,” I reply. “Let me just shove this yoke back on.”

He glosses his choice of an ending: “In the 1980s there was this lad writing on the Tipperary Star called ‘Tales of the Gael’. Around 1983, he went up to Dublin and met a former hurler named Tommy Treacy, who was a man of the 1920s and ’30s.

“Tommy was in a flat in Phibsboro, and this man, when he came back down to Tipp, published a poem in the Star. I cut it out, and I’m probably the only eejit left in the world who remembers it.”

Then Tony Wall throws back his head and half sings five verses, finishing with this one:

I bade goodbye and left him sitting there,

The old Tipperary hurler in his upright chair.

Although old and grey and full of years at last

His thoughts are those of youthful days now past.