48cm x 43cm

The

Irish Volunteers (

Irish:

Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the

Irish Volunteer Force[3][4][5] or

Irish Volunteer Army,

was a military organisation established in 1913 by

Irish nationalists and

republicans. It was ostensibly formed in response to the formation of its Irish unionist/loyalist counterpart the

Ulster Volunteers in 1912, and its declared primary aim was "to secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to the whole people of Ireland".

The Volunteers included members of the

Gaelic League,

Ancient Order of Hibernians and

Sinn Féin,

and, secretly, the

Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Increasing rapidly to a strength of nearly 200,000 by mid-1914, it split in September of that year over

John Redmond's commitment to the

British war effort, with the smaller group retaining the name of "Irish Volunteers".

Formation

Home Rule for Ireland dominated political debate between the two countries since Prime Minister

William Ewart Gladstoneintroduced the first

Home Rule Bill in 1886, intended to grant a measure of self-government and national autonomy to Ireland, but which was rejected by the House of Commons. The second Home Rule Bill, seven years later having passed the House of Commons, was vetoed by the

House of Lords. It would be the

third Home Rule Bill, introduced in 1912, which would lead to the crisis in Ireland between the majority Nationalist population and the Unionists in Ulster.

On 28 September 1912 at

Belfast City Hall just over 450,000

Unionists signed the

Ulster Covenant to resist the granting of Home Rule. This was followed in January 1913 with the formation of the

Ulster Volunteers composed of adult male Unionists to oppose the passage and implementation of the bill by force of arms if necessary.

The establishment of the Ulster Volunteers was (according to

Eoin MacNeill) instigated, approved, and financed by English Tories with the other major British party, the Liberals, not finding "itself terribly distressed by that proceeding."

Initiative

The initiative for a series of meetings leading up to the public inauguration of the Irish Volunteers came from the

Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

Bulmer Hobson, co-founder of the republican boy scouts,

Fianna Éireann, and member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, believed the IRB should use the formation of the Ulster Volunteers as an "excuse to try to persuade the public to form an Irish volunteer force".

The IRB could not move in the direction of a volunteer force themselves, as any such action by known proponents of physical force would be suppressed, despite the precedent established by the Ulster Volunteers. They therefore confined themselves to encouraging the view that nationalists also ought to organise a volunteer force for the defence of Ireland. A small committee then began to meet regularly in Dublin from July 1913, who watched the growth of this opinion.

They refrained however from any action until the precedent of Ulster should have first been established while waiting for the lead to come from a "constitutional" quarter.

The IRB began the preparations for the open organisation of the Irish Volunteers in January 1913. James Stritch, an IRB member, had the

Irish National Foresters build a hall at the back of 41

Parnell Square in Dublin, which was the headquarters of the

Wolfe Tone Clubs. Anticipating the formation of the Volunteers they began to learn foot-drill and military movements.

The drilling was conducted by Stritch together with members of Fianna Éireann. They began by drilling a small number of IRB associated with the Dublin

Gaelic Athletic Association, led by

Harry Boland.

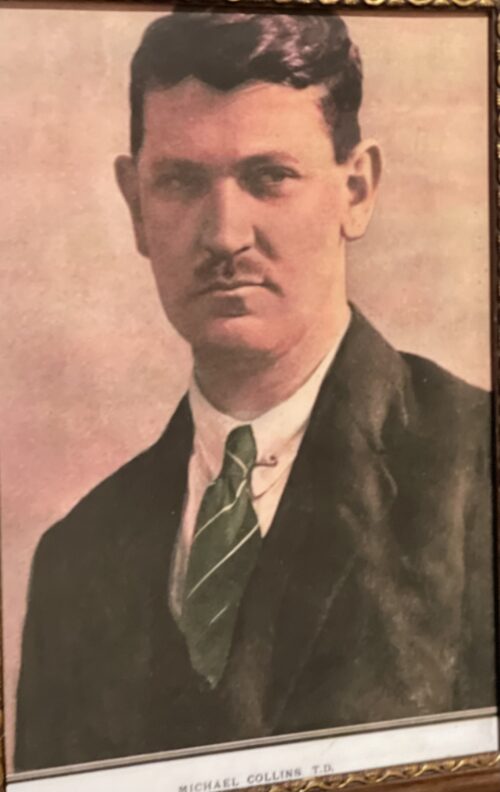

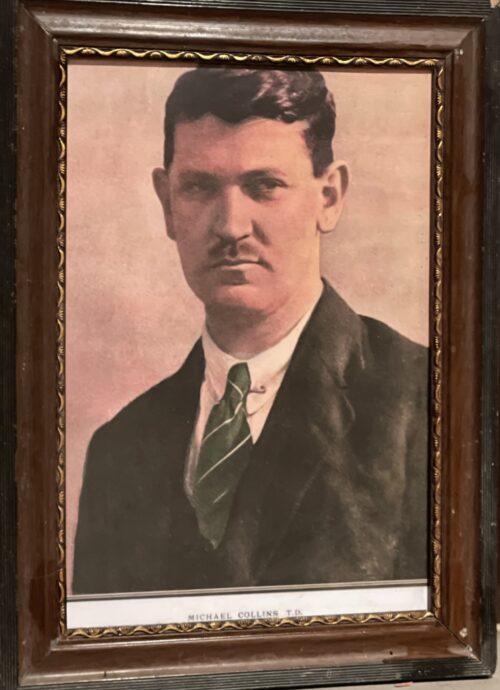

Michael Collins along with several other IRB members claim that the formation of the Irish Volunteers was not merely a "knee-jerk reaction" to the Ulster Volunteers, which is often supposed, but was in fact the "old Irish Republican Brotherhood in fuller force."

"The North Began"

The IRB knew they would need a highly regarded figure as a public front that would conceal the reality of their control.

The IRB found in

Eoin MacNeill, Professor of Early and Medieval History at

University College Dublin, the ideal candidate. McNeill's academic credentials and reputation for integrity and political moderation had widespread appeal.

The O'Rahilly, assistant editor and circulation manager of the

Gaelic League newspaper

An Claidheamh Soluis, encouraged MacNeill to write an article for the first issue of a new series of articles for the paper.

The O'Rahilly suggested to MacNeill that it should be on some wider subject than mere Gaelic pursuits. It was this suggestion which gave rise to the article entitled

The North Began, giving the Irish Volunteers its public origins. On 1 November, MacNeill's article suggesting the formation of an Irish volunteer force was published.

MacNeill wrote,

There is nothing to prevent the other twenty-eight counties from calling into existence citizen forces to hold Ireland "for the Empire". It was precisely with this object that the Volunteers of 1782 were enrolled, and they became the instrument of establishing Irish self-government.

After the article was published, Hobson asked The O'Rahilly to see MacNeill, to suggest to him that a conference should be called to make arrangements for publicly starting the new movement.

The article "threw down the gauntlet to nationalists to follow the lead given by Ulster unionists."

MacNeill was unaware of the detailed planning which was going on in the background, but was aware of Hobson's political leanings. He knew the purpose as to why he was chosen, but he was determined not to be a puppet.

Launch

With MacNeill willing to take part, O'Rahilly and Hobson sent out invitations for the first meeting at Wynn's Hotel in Abbey Street, Dublin, on 11 November.

Hobson himself did not attend this meeting, believing his standing as an "extreme nationalist" might prove problematical.

The IRB, however, was well represented by, among others,

Seán Mac Diarmada and

Éamonn Ceannt, who would prove to be substantially more extreme than Hobson.

Several others meetings were soon to follow, as prominent nationalists planned the formation of the Volunteers, under the leadership of MacNeill.

Meanwhile, labour leaders in Dublin began calling for the establishment of a citizens' defence force in the aftermath of the

lock out of 19 August 1913.

Thus formed the

Irish Citizen Army, led by

James Larkin and

James Connolly, which, though it had similar aims, at this point had no connection with the Irish Volunteers (were later allies in the

Easter Rising.

The Volunteer organisation was publicly launched on 25 November, with their first public meeting and enrolment rally at the

Rotunda in Dublin.

The IRB organised this meeting to which all parties were invited,

and brought 5000 enlistment blanks for distribution and handed out in books of one hundred each to each of the stewards. Every one of the stewards and officials wore on their lapel a small silken bow the centre of which was white, while on one side was green and on the other side orange and had long been recognised as the colours which the Irish Republican Brotherhood had adopted as the Irish national banner.

The hall was filled to its 4,000 person capacity, with a further 3,000 spilling onto the grounds outside. Speakers at the rally included MacNeill,

Patrick Pearse, and Michael Davitt, son of the

Land League founder

of the same name. Over the course of the following months the movement spread throughout the country, with thousands more joining every week.

Organisation and leadership

The original members of the Provisional Committee were:

- Members: Piaras Béaslaí (Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB)), Sir Roger Casement (GL), Éamonn Ceannt (IRB, GL, SF), John Fitzgibbon (GL, SF), Liam Gogan, Bulmer Hobson (IRB, Fianna Éireann (FÉ)), Michael J. Judge (AOH), Thomas Kettle (IPP, AOH), James Lenehan (AOH), Michael Lonergan (IRB, Fianna Éireann (FÉ)), Peter (Peadar) Macken (IRB, Labour leader, SF, GL), Seán Mac Diarmada (IRB, Irish Freedom), Thomas MacDonagh (GL), Liam Mellows (IRB), Maurice Moore (IPP, GL, Connaught Rangers), Séamus O'Connor (IRB), Colm O'Loughlin (IRB, St. Enda's School (SES)), Peter O'Reilly (Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH)), Robert Page (IRB, Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA)), Patrick Pearse (GL, SES), Joseph M. Plunkett (GL, Irish Review), John Walsh (AOH), Peter White (Celtic Literary Society);

- Fianna Éireann representatives: Con Colbert (IRB), Eamon Martin (IRB), Patrick O'Riain (IRB).

The Manifesto of the Irish Volunteers was composed by MacNeill, with some minimal changes added by Tom Kettle and other members of the Provisional Committee.

It stated that the organisation's objectives were "to secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to the whole people of Ireland", and that membership was open to all Irishmen "without distinction of creed, politics or social grade."

Though the "rights and liberties" were never defined, nor the means by which they would be obtained, the IRB in the Fenian tradition construed the term to mean the maintenance of the rights of Ireland to national independence and to secure that right in arms.

The manifesto further stated that their duties were to be defensive, contemplating neither "aggression or domination". It said that the Tory policy in Ulster was deliberately adopted to make the display of military force with the threat of armed violence the decisive factor in relations between Ireland and Great Britain. If Irishmen accepted this new policy he said they would be surrendering their rights as men and citizens. If they did not attempt to defeat this policy "we become politically the most degraded population in Europe and no longer worthy of the name of nation." In this situation, it said,"the duty of safeguarding our own rights is our duty first and foremost. They have rights who dare maintain them."

But rights, in the last resort, could only be maintained by arms.

MacNeill himself would approve of armed resistance only if the British launched a campaign of repression against Irish nationalist movements, or if they attempted to impose conscription on Ireland following the outbreak of the

First World War, in such a case he believed that they would have mass support.

John Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party

While the IRB was instrumental in the establishment of the Volunteers, they were never able to gain complete control of the organisation. This was compounded after

John Redmond, leader of the

Irish Parliamentary Party, took an active interest. Though some well known Redmond supporters had joined the Volunteers, the attitude of Redmond and the Party was largely one of opposition, though by the Summer of 1914, it was clear the IPP needed to control the Volunteers if they were not to be a threat to their authority.

The majority of the IV members, like the nation as a whole, were supporters of Redmond (though this was not necessarily true of the organisation's leadership), and, armed with this knowledge, Redmond sought IPP influence, if not outright control of the Volunteers. Negotiations between MacNeil and Redmond over the latter's future role continued inconclusively for several weeks, until on 9 June Redmond issued an ultimatum, through the press, demanding the Provisional Committee co-opt twenty-five IPP nominees.

With several IPP members and their supporters on the committee already, this would give them a majority of seats, and effective control.

The more moderate members of the Volunteers' Provisional Committee did not like the idea, nor the way it was presented, but they were largely prepared to go along with it to prevent Redmond from forming a rival organisation, which would draw away most of their support. The IRB was completely opposed to Redmond's demands, as this would end any chance they had of controlling the Volunteers. Hobson, who simultaneously served in leadership roles in both the IRB and the Volunteers, was one of a few IRB members to reluctantly submit to Redmond's demands, leading to a falling out with the IRB leaders, notably

Tom Clarke. In the end the Committee accepted Redmond's demands, by a vote of 18 to 9, most of the votes of dissent coming from members of the IRB.

The new IPP members of the committee included MP

Joseph Devlin and Redmond's son

William, but were mostly composed of insignificant figures, believed to have been appointed as a reward for party loyalty.

[46] Despite their numbers, they were never able to exert control over the organisation, which largely remained with its earlier officers. Finances remained fully in the hands of the treasurer,

The O'Rahilly, his assistant,

Éamonn Ceannt, and MacNeill himself, who retained his position as chairman, further diminishing the IPP's influence.

Arming the Volunteers

Shortly after the formation of the Volunteers, the

British Parliament banned the importation of weapons into Ireland. The "

Curragh incident" (also referred to as the "Curragh Mutiny") of March 1914, indicated that the government could not rely on its army to ensure a smooth transition to Home Rule.

Then in April 1914 the

Ulster Volunteerssuccessfully imported 24,000 rifles in the

Larne Gun Running event. The Irish Volunteers realised that it too would have to follow suit if they were to be taken as a serious force. Indeed, many contemporary observers commented on the irony of "loyal" Ulstermen arming themselves and threatening to defy the British government by force.

Patrick Pearsefamously replied that "the

Orangeman with a gun is not as laughable as the nationalist without one." Thus O'Rahilly, Sir

Roger Casement and

Bulmer Hobson worked together to co-ordinate

a daylight gun-running expedition to

Howth, just north of

Dublin.

The plan worked, and

Erskine Childers brought nearly 1,000 rifles, purchased from Germany, to the harbour on 26 July and distributed them to the waiting Volunteers, without interference from the authorities. The remainder of the guns smuggled from Germany for the Irish Volunteers were landed at

Kilcoole a week later by Sir

Thomas Myles.

As the Volunteers marched from Howth back to Dublin, however, they were met by a large patrol of the

Dublin Metropolitan Police and the

King's Own Scottish Borderers. The Volunteers escaped largely unscathed, but when the Borderers returned to Dublin they clashed with a group of unarmed civilians who had been heckling them at

Bachelors Walk. Though no order was given, the soldiers fired on the civilians, killing four and further wounding 37. This enraged the populace, and during the outcry enlistments in the Volunteers soared.

The Split

The outbreak of

World War I in August 1914 provoked a serious split in the organisation. Redmond, in the interest of ensuring the enactment of the

Home Rule Act 1914 then on the statute books, encouraged the Volunteers to support the British and

Allied war commitment and join

Irish regiments of the British

New Army divisions, an action which angered the founding members. Given the wide expectation that the war was going to be a short one, the majority however

supported the war effort and the call to restore the "freedom of small nations" on the European continent. They left to form the

National Volunteers, some of whose members fought in the

10th and

16th (Irish) Division, side by side with their Ulster Volunteer counterparts from the

36th (Ulster) Division.

A minority believed that the principles used to justify the Allied war cause were best applied in restoring the freedom to one small country in particular. They retained the name "Irish Volunteers", were led by MacNeill and called for Irish neutrality. The National Volunteers kept some 175,000 members, leaving the Irish Volunteers with an estimated 13,500. However, the National Volunteers declined rapidly, and the few remaining members reunited with the Irish Volunteers in October 1917.

The split proved advantageous to the IRB, which was now back in a position to control the organisation.

Following the split, the remnants of the Irish Volunteers were often, and erroneously, referred to as the "Sinn Féin Volunteers", or, by the British press, derisively as "Shinners", after

Arthur Griffith's political organisation

Sinn Féin. Although the two organisations had some overlapping membership, there was no official connection between Griffith's then moderate Sinn Féin and the Volunteers. The political stance of the remaining Volunteers was not always popular, and a 1,000-strong march led by Pearse through the garrison city of

Limerick on

Whit Sunday, 1915, was pelted with rubbish by a hostile crowd. Pearse explained the reason for the establishment of the new force when he said in May 1915:

What if conscription be enforced on Ireland? What if a Unionist or a Coalition British Ministry repudiates the Home Rule Act?

What if it be determined to dismember Ireland? The future is big with these and other possibilities.

After the departure of Redmond and his followers, the Volunteers adopted a constitution, which had been drawn up by the earlier provisional committee, and was ratified by a convention of 160 delegates on 25 October 1914. It called for general council of fifty members to meet monthly, as well as an executive of the president and eight elected members. In December a headquarters staff was appointed, consisting of

Eoin MacNeill as chief of staff,

The O'Rahilly as director of arms,

Thomas MacDonagh as director of training,

Patrick Pearse as director of military organisation,

Bulmer Hobson as quartermaster, and

Joseph Plunkett as director of military operations. The following year they were joined by

Éamonn Ceannt as director of communications and J.J. O'Connell as chief of inspection.

This reorganisation put the IRB is a stronger position, as four important military positions (director of training, director of military organisation, director of military operations, and director of communications) were held by men who were, or would soon be, members of the IRB, and who later become four of the seven signatories of the

Easter Proclamation. (Hobson was also an IRB member, but had a falling out with the leadership after he supported Redmond's appointees to the provisional council, and hence played little role in the IRB thereafter.)

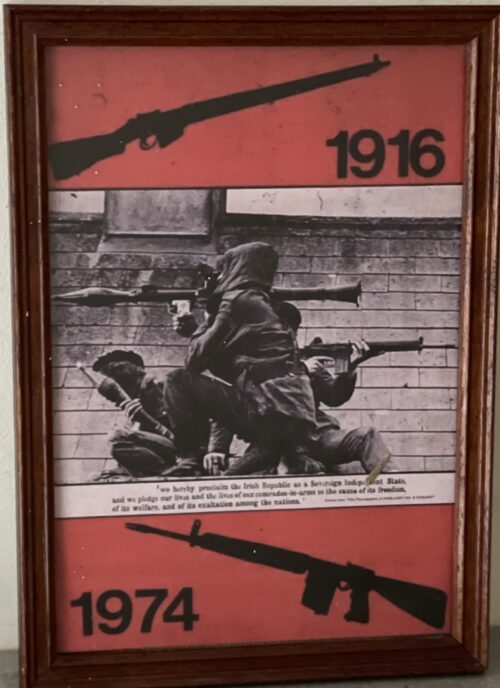

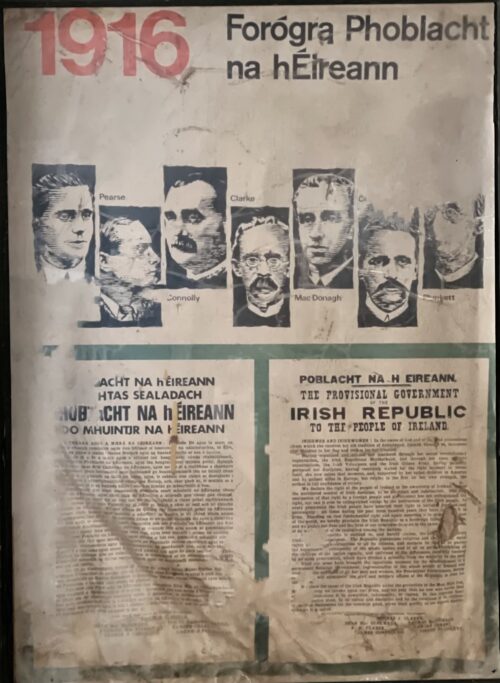

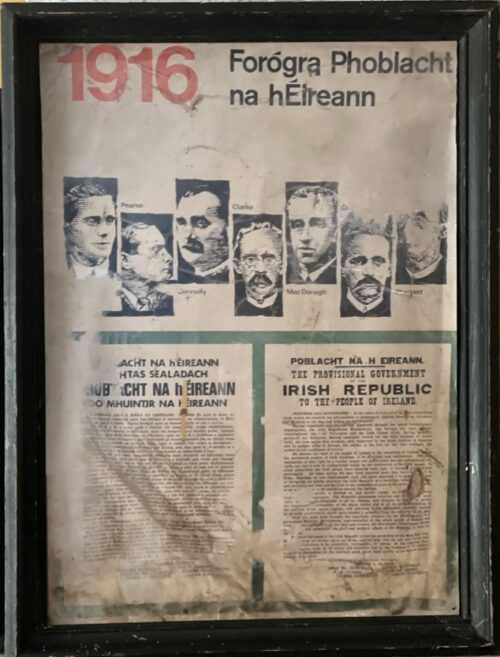

Easter Rising, 1916

The official stance of the Irish Volunteers was that action would only be taken were the British authorities at

Dublin Castle to attempt to disarm the Volunteers, arrest their leaders, or introduce

conscription to Ireland.The IRB, however, was determined to use the Volunteers for offensive action while Britain was tied up in the First World War. Their plan was to circumvent MacNeill's command, instigating a

Rising, and to get MacNeill on board once the rising was a

fait accompli.

Pearse issued orders for three days of parades and manoeuvres, a thinly disguised order for a general insurrection.

MacNeill soon discovered the real intent behind the orders and attempted to stop all actions by the Volunteers. He succeeded only in putting the Rising off for a day, and limiting it to about 1,000 active participants within Dublin and a very limited action elsewhere. Almost all of the fighting was confined to Dublin - though the Volunteers were involved in engagements against RIC barracks in

Ashbourne, County Meath,

and there were actions in

Enniscorthy,

County Wexford and in

County Galway.

The

Irish Citizen Army supplied slightly more than 200 personnel for the Dublin campaign.

Reorganisation

Steps towards reorganising the Irish Volunteers were taken during 1917, and on 27 October 1917 a convention was held in Dublin. This convention was called to coincide with the

Sinn Féin party conference. Nearly 250 people attended the convention; internment prevented many more from attending. The

Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) estimated that 162 companies of volunteers were active in the country, although other sources suggest a figure of 390.

The proceedings were presided over by

Éamon de Valera, who had been elected President of Sinn Féin the previous day. Also on the platform were

Cathal Brugha and many others who were prominent in the reorganising of the Volunteers in the previous few months, many of them ex-prisoners.

De Valera was elected president. A national executive was also elected, composed of representatives of all parts of the country. In addition, a number of directors were elected to head the various IRA departments. Those elected were:

Michael Collins (Director for Organisation);

Richard Mulcahy (Director of Training);

Diarmuid Lynch (Director for Communications);

Michael Staines (Director for Supply);

Rory O'Connor (Director of Engineering).

Seán McGarry was voted general secretary, while Cathal Brugha was made Chairman of the Resident Executive, which in effect made him Chief of Staff.

The other elected members were:

M. W. O'Reilly (Dublin);

Austin Stack (

Kerry);

Con Collins (

Limerick);

Seán MacEntee (

Belfast);

Joseph O'Doherty (

Donegal);

Paul Galligan(

Cavan);

Eoin O'Duffy (

Monaghan);

Séamus Doyle (

Wexford);

Peadar Bracken (

Offaly);

Larry Lardner (

Galway);

Richard Walsh (

Mayo) and another member from

Connacht. There were six co-options to make-up the full number when the directors were named from within their ranks. The six were all Dublin men:

Eamonn Duggan;

Gearóid O'Sullivan;

Fintan Murphy;

Diarmuid O'Hegarty;

Dick McKee and Paddy Ryan.

Of the 26 elected, six were also members of the Sinn Féin National Executive, with Éamon de Valera president of both. Eleven of the 26 were elected

Teachta Dála (members of the Dáil) in the

1918 general election and 13 in the May 1921 election.

Relationship with Dáil Éireann

Sinn Féin MPs elected in 1918 fulfilled their election promise not to take their seats in Westminster but instead set up an independent "Assembly of Ireland", or

Dáil Éireann, in the

Irish language. In theory, the Volunteers were responsible to the Dáil and was the army of the Irish Republic. In practice, the Dáil had great difficulty controlling their actions; under their own constitution, the Volunteers were bound to obey their own executive and no other body.

The fear was increased when, on the very day the new national parliament was meeting, 21 January 1919, members of the

Third Tipperary Brigade led by

Séumas Robinson,

Seán Treacy,

Dan Breen and

Seán Hogan carried out the

Soloheadbeg Ambush and seized a quantity of

gelignite, killing two RIC constables and triggering the

War of Independence. Technically, the men involved were considered to be in a serious breach of Volunteer discipline and were liable to be court-martialed, but it was considered more politically expedient to hold them up as examples of a rejuvenated militarism. The conflict soon escalated into

guerrilla warfare by what were then known as the

Flying Columns in remote areas. Attacks on remote RIC barracks continued throughout 1919 and 1920, forcing the police to consolidate defensively in the larger towns, effectively placing large areas of the countryside in the hands of the Republicans.

Moves to make the Volunteers the army of the Dáil and not its rival had begun before the January attack, and were stepped up. On 31 January 1919 the Volunteer organ,

An tÓglách ("The Volunteer") published a list of principles agreed between two representatives of the Aireacht, acting Príomh Aire Cathal Brugha and

Richard Mulcahy and the Executive. It made first mention of the organisation treating "the armed forces of the enemy – whether soldiers or policemen – exactly as a

national army would treat the members of an invading army".

In the statement the new relationship between the Aireacht and the Volunteers – who increasingly became known as the

Irish Republican Army (IRA) – was defined clearly.

- The Government was defined as possessing the same power and authority as a normal government.

- It, and not the IRA, sanctions the IRA campaign;

- It explicitly spoke of a state of war.

As part of the ongoing strategy to take control of the IRA, Brugha proposed to

Dáil Éireann on 20 August 1919 that the Volunteers were to be asked, at this next convention, to swear allegiance to the Dáil. He further proposed that members of the Dáil themselves should swear the same oath.

On 25 August Collins wrote to the First minister (Príomh Aire), Éamon de Valera, to inform him "the Volunteer affair is now fixed". Though it was "fixed" at one level, another year passed before the Volunteers took an oath of allegiance to the Irish Republic and its government, "throughout August 1920".

On 11 March 1921 Dáil Éireann discussed its relationship with its army. De Valera commented that "..the Dáil was hardly acting fairly by the army in not publicly taking full responsibility for all its acts." The Dáil had not yet declared war, but was at war; it voted unanimously that "..they should agree to the acceptance of a state of war."

Legacy

All organisations calling themselves the

IRA, as well as the

Irish Defence Forces (IDF), have their origins in the Irish Volunteers. The Irish name of the Volunteers,

Óglaigh na hÉireann, was retained when the English name changed, and is the official Irish name of the IDF, as well as the various IRAs.

The name of the

Bengal Volunteers, an Indian revolutionary organization founded in 1928 and active against British rule in India, may have been inspired by the Irish organization.