-

32cm x 28cm Originating from an pub in Co Kerry -this innuendo laden election poster will catch the eye in any bar ! Richard Nixon’s mother Hannah was descended from the Milhous family, Irish Quakers from Timahoe, Kildare while the first Nixon to arrive in the US, James, left Ireland in 1731. President Nixon visited the small town in October 1970 during a state visit to Ireland. He is the only US president to date to resign from office following his involvement in the Watergate scandal.

32cm x 28cm Originating from an pub in Co Kerry -this innuendo laden election poster will catch the eye in any bar ! Richard Nixon’s mother Hannah was descended from the Milhous family, Irish Quakers from Timahoe, Kildare while the first Nixon to arrive in the US, James, left Ireland in 1731. President Nixon visited the small town in October 1970 during a state visit to Ireland. He is the only US president to date to resign from office following his involvement in the Watergate scandal. -

64cm x 50cm John Jameson was originally a lawyer from Alloa in Scotland before he founded his eponymous distillery in Dublin in 1780.Prevoius to this he had made the wise move of marrying Margaret Haig (1753–1815) in 1768,one of the simple reasons being Margaret was the eldest daughter of John Haig, the famous whisky distiller in Scotland. John and Margaret had eight sons and eight daughters, a family of 16 children. Portraits of the couple by Sir Henry Raeburn are on display in the National Gallery of Ireland. John Jameson joined the Convivial Lodge No. 202, of the Dublin Freemasons on the 24th June 1774 and in 1780, Irish whiskey distillation began at Bow Street. In 1805, he was joined by his son John Jameson II who took over the family business that year and for the next 41 years, John Jameson II built up the business before handing over to his son John Jameson the 3rd in 1851. In 1901, the Company was formally incorporated as John Jameson and Son Ltd. Four of John Jameson’s sons followed his footsteps in distilling in Ireland, John Jameson II (1773 – 1851) at Bow Street, William and James Jameson at Marrowbone Lane in Dublin (where they partnered their Stein relations, calling their business Jameson and Stein, before settling on William Jameson & Co.). The fourth of Jameson's sons, Andrew, who had a small distillery at Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, was the grandfather of Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of wireless telegraphy. Marconi’s mother was Annie Jameson, Andrew’s daughter. John Jameson’s eldest son, Robert took over his father’s legal business in Alloa. The Jamesons became the most important distilling family in Ireland, despite rivalry between the Bow Street and Marrowbone Lane distilleries. By the turn of the 19th century, it was the second largest producer in Ireland and one of the largest in the world, producing 1,000,000 gallons annually. Dublin at the time was the centre of world whiskey production. It was the second most popular spirit in the world after rum and internationally Jameson had by 1805 become the world's number one whiskey. Today, Jameson is the world's third largest single-distillery whiskey. Historical events, for a time, set the company back. The temperance movement in Ireland had an enormous impact domestically but the two key events that affected Jameson were the Irish War of Independence and subsequent trade war with the British which denied Jameson the export markets of the Commonwealth, and shortly thereafter, the introduction of prohibition in the United States. While Scottish brands could easily slip across the Canada–US border, Jameson was excluded from its biggest market for many years. The introduction of column stills by the Scottish blenders in the mid-19th-century enabled increased production that the Irish, still making labour-intensive single pot still whiskey, could not compete with. There was a legal enquiry somewhere in 1908 to deal with the trade definition of whiskey. The Scottish producers won within some jurisdictions, and blends became recognised in the law of that jurisdiction as whiskey. The Irish in general, and Jameson in particular, continued with the traditional pot still production process for many years.In 1966 John Jameson merged with Cork Distillers and John Powers to form the Irish Distillers Group. In 1976, the Dublin whiskey distilleries of Jameson in Bow Street and in John's Lane were closed following the opening of a New Midleton Distillery by Irish Distillers outside Cork. The Midleton Distillery now produces much of the Irish whiskey sold in Ireland under the Jameson, Midleton, Powers, Redbreast, Spot and Paddy labels. The new facility adjoins the Old Midleton Distillery, the original home of the Paddy label, which is now home to the Jameson Experience Visitor Centre and the Irish Whiskey Academy. The Jameson brand was acquired by the French drinks conglomerate Pernod Ricard in 1988, when it bought Irish Distillers. The old Jameson Distillery in Bow Street near Smithfield in Dublin now serves as a museum which offers tours and tastings. The distillery, which is historical in nature and no longer produces whiskey on site, went through a $12.6 million renovation that was concluded in March 2016, and is now a focal part of Ireland's strategy to raise the number of whiskey tourists, which stood at 600,000 in 2017.Bow Street also now has a fully functioning Maturation Warehouse within its walls since the 2016 renovation. It is here that Jameson 18 Bow Street is finished before being bottled at Cask Strength. In 2008, The Local, an Irish pub in Minneapolis, sold 671 cases of Jameson (22 bottles a day),making it the largest server of Jameson's in the world – a title it

64cm x 50cm John Jameson was originally a lawyer from Alloa in Scotland before he founded his eponymous distillery in Dublin in 1780.Prevoius to this he had made the wise move of marrying Margaret Haig (1753–1815) in 1768,one of the simple reasons being Margaret was the eldest daughter of John Haig, the famous whisky distiller in Scotland. John and Margaret had eight sons and eight daughters, a family of 16 children. Portraits of the couple by Sir Henry Raeburn are on display in the National Gallery of Ireland. John Jameson joined the Convivial Lodge No. 202, of the Dublin Freemasons on the 24th June 1774 and in 1780, Irish whiskey distillation began at Bow Street. In 1805, he was joined by his son John Jameson II who took over the family business that year and for the next 41 years, John Jameson II built up the business before handing over to his son John Jameson the 3rd in 1851. In 1901, the Company was formally incorporated as John Jameson and Son Ltd. Four of John Jameson’s sons followed his footsteps in distilling in Ireland, John Jameson II (1773 – 1851) at Bow Street, William and James Jameson at Marrowbone Lane in Dublin (where they partnered their Stein relations, calling their business Jameson and Stein, before settling on William Jameson & Co.). The fourth of Jameson's sons, Andrew, who had a small distillery at Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, was the grandfather of Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of wireless telegraphy. Marconi’s mother was Annie Jameson, Andrew’s daughter. John Jameson’s eldest son, Robert took over his father’s legal business in Alloa. The Jamesons became the most important distilling family in Ireland, despite rivalry between the Bow Street and Marrowbone Lane distilleries. By the turn of the 19th century, it was the second largest producer in Ireland and one of the largest in the world, producing 1,000,000 gallons annually. Dublin at the time was the centre of world whiskey production. It was the second most popular spirit in the world after rum and internationally Jameson had by 1805 become the world's number one whiskey. Today, Jameson is the world's third largest single-distillery whiskey. Historical events, for a time, set the company back. The temperance movement in Ireland had an enormous impact domestically but the two key events that affected Jameson were the Irish War of Independence and subsequent trade war with the British which denied Jameson the export markets of the Commonwealth, and shortly thereafter, the introduction of prohibition in the United States. While Scottish brands could easily slip across the Canada–US border, Jameson was excluded from its biggest market for many years. The introduction of column stills by the Scottish blenders in the mid-19th-century enabled increased production that the Irish, still making labour-intensive single pot still whiskey, could not compete with. There was a legal enquiry somewhere in 1908 to deal with the trade definition of whiskey. The Scottish producers won within some jurisdictions, and blends became recognised in the law of that jurisdiction as whiskey. The Irish in general, and Jameson in particular, continued with the traditional pot still production process for many years.In 1966 John Jameson merged with Cork Distillers and John Powers to form the Irish Distillers Group. In 1976, the Dublin whiskey distilleries of Jameson in Bow Street and in John's Lane were closed following the opening of a New Midleton Distillery by Irish Distillers outside Cork. The Midleton Distillery now produces much of the Irish whiskey sold in Ireland under the Jameson, Midleton, Powers, Redbreast, Spot and Paddy labels. The new facility adjoins the Old Midleton Distillery, the original home of the Paddy label, which is now home to the Jameson Experience Visitor Centre and the Irish Whiskey Academy. The Jameson brand was acquired by the French drinks conglomerate Pernod Ricard in 1988, when it bought Irish Distillers. The old Jameson Distillery in Bow Street near Smithfield in Dublin now serves as a museum which offers tours and tastings. The distillery, which is historical in nature and no longer produces whiskey on site, went through a $12.6 million renovation that was concluded in March 2016, and is now a focal part of Ireland's strategy to raise the number of whiskey tourists, which stood at 600,000 in 2017.Bow Street also now has a fully functioning Maturation Warehouse within its walls since the 2016 renovation. It is here that Jameson 18 Bow Street is finished before being bottled at Cask Strength. In 2008, The Local, an Irish pub in Minneapolis, sold 671 cases of Jameson (22 bottles a day),making it the largest server of Jameson's in the world – a title it -

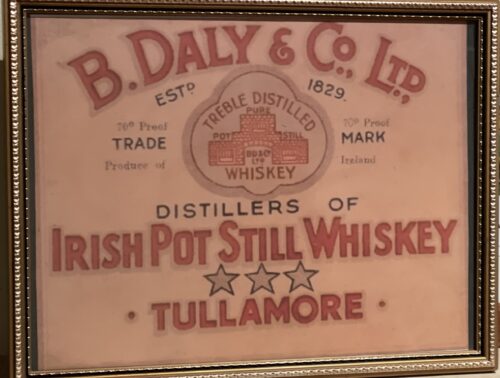

45cm x 34cmThe Tullamore Distillery was founded in 1829 by Michael Molloy, in Tullamore, County Offaly, Ireland. When Molloy dead, in 1846, the distillery passed into the hands of one of his five nephews, Bernard Daly, and under the general management of Daniel E. Williams. 40 years later, in 1887, Bernard Daly died, and Tullamore Distillery passed to his son Captain Bernard Daly, who left, as always, the running of the distillery to Daniel E. Williams. Under Daniel E. Williams, the Tullamore Distillery expanded and prospered, lunching the whiskey which still bears his initials, Tullamore D.E.W. Williams was very resourceful and brought electricity to Tullamore in 1893. He installed telephones and motorised automobiles in the distillery. In 1903, the distillery was incorporated into a company under the name B Daly & Co. Ltd., of which both Daly and Williams had shares. The Tullamore Distillery, finally, came under complete control of Williams family in 1931. From 1925 to 1937, due to the advent of competition and to cut costs, Tullamore Distillery was temporarily mothballed. In the 1940s, Desmond, the grandson of Daniel E. Williams, began into alternative products, and with whiskey sales still languishing, the company decided to focus its resources on the liqueur Irish Mist. Therefore, distilling operations ceased in Tullamore in 1954, and production was temporarily moved to Power's Distillery in Dublin, and was later moved to Midleton Distillery and Bushmill's Distillery. William Grant & Sons acquired Tullamore brand in 2010 and, in March 2012, they announced that they were in the final stages of negotiations to acquire a site at Clonminch, situated on the outskirts of Tullamore. Construction of a new distillery began in May 2013 and in autumn 2014, the distillery was ready to start production in its ancestral home of Tullamore. The construction will be executed in three phases where the first was a pot still distillery with the possibility to distil 1,8 million litres per year. In early 2016, it was increased to 3,6 million litres by the addition of more stills and washbacks. Finally, a grain distillery and bottling plant were added in 2017. Tullamore can now produce all three components of its Tullamore D.E.W. blended whiskey on-site.

45cm x 34cmThe Tullamore Distillery was founded in 1829 by Michael Molloy, in Tullamore, County Offaly, Ireland. When Molloy dead, in 1846, the distillery passed into the hands of one of his five nephews, Bernard Daly, and under the general management of Daniel E. Williams. 40 years later, in 1887, Bernard Daly died, and Tullamore Distillery passed to his son Captain Bernard Daly, who left, as always, the running of the distillery to Daniel E. Williams. Under Daniel E. Williams, the Tullamore Distillery expanded and prospered, lunching the whiskey which still bears his initials, Tullamore D.E.W. Williams was very resourceful and brought electricity to Tullamore in 1893. He installed telephones and motorised automobiles in the distillery. In 1903, the distillery was incorporated into a company under the name B Daly & Co. Ltd., of which both Daly and Williams had shares. The Tullamore Distillery, finally, came under complete control of Williams family in 1931. From 1925 to 1937, due to the advent of competition and to cut costs, Tullamore Distillery was temporarily mothballed. In the 1940s, Desmond, the grandson of Daniel E. Williams, began into alternative products, and with whiskey sales still languishing, the company decided to focus its resources on the liqueur Irish Mist. Therefore, distilling operations ceased in Tullamore in 1954, and production was temporarily moved to Power's Distillery in Dublin, and was later moved to Midleton Distillery and Bushmill's Distillery. William Grant & Sons acquired Tullamore brand in 2010 and, in March 2012, they announced that they were in the final stages of negotiations to acquire a site at Clonminch, situated on the outskirts of Tullamore. Construction of a new distillery began in May 2013 and in autumn 2014, the distillery was ready to start production in its ancestral home of Tullamore. The construction will be executed in three phases where the first was a pot still distillery with the possibility to distil 1,8 million litres per year. In early 2016, it was increased to 3,6 million litres by the addition of more stills and washbacks. Finally, a grain distillery and bottling plant were added in 2017. Tullamore can now produce all three components of its Tullamore D.E.W. blended whiskey on-site.- 1829 Tullamore Distillery was founded by Michael Molloy, in Tullamore, County Offaly, Ireland

- 1846 Molloy dead and the distillery passed into the hands of one of his five nephews, Bernard Daly

- 1887 Bernard Daly dead and Tullamore Distillery passed to his son Captain B. Daly

- 1893 Williams brought electricity to Tullamore

- 1903 The distillery was incorporate under tha name B Daly & Co. Ltd.

- 1925-1937 Tullamore Distillery was temporarily closed

- 1931 Tullamore came under complete control of Williams family

- 1954 The old Tullamore Distillery closed and production was transferred to the Midleton Distillery

- 2010 The brand was purchased by William Grant & Sons, who invested €35 million in the construction of the new Tullamore Distillery

- 2014 The new Tullamore Distillery opened

-

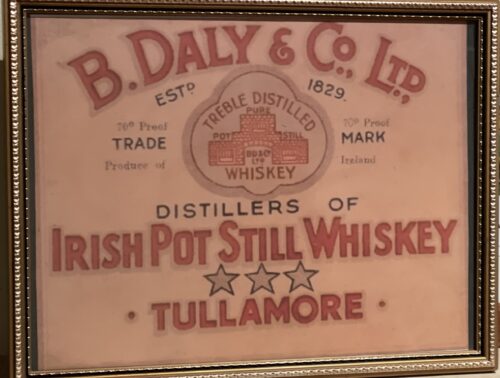

44cm x 33cm Limerick In 1791 James Power, an innkeeper from Dublin, established a small distillery at his public house at 109 Thomas St., Dublin. The distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son, and had moved to a new premises at John's Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O'Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the "Big Four") came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John's Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as "about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere". At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:"The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels." The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power's Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John's Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John's Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John's Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery's pot stills were saved and now located in the college's Red Square.

44cm x 33cm Limerick In 1791 James Power, an innkeeper from Dublin, established a small distillery at his public house at 109 Thomas St., Dublin. The distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son, and had moved to a new premises at John's Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O'Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the "Big Four") came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John's Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as "about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere". At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:"The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels." The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power's Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John's Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John's Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John's Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery's pot stills were saved and now located in the college's Red Square. The Still House at John's Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

The Still House at John's Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

-

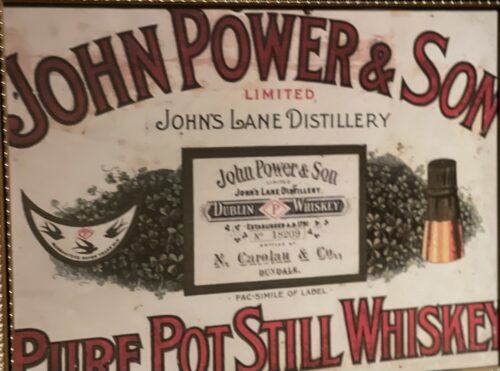

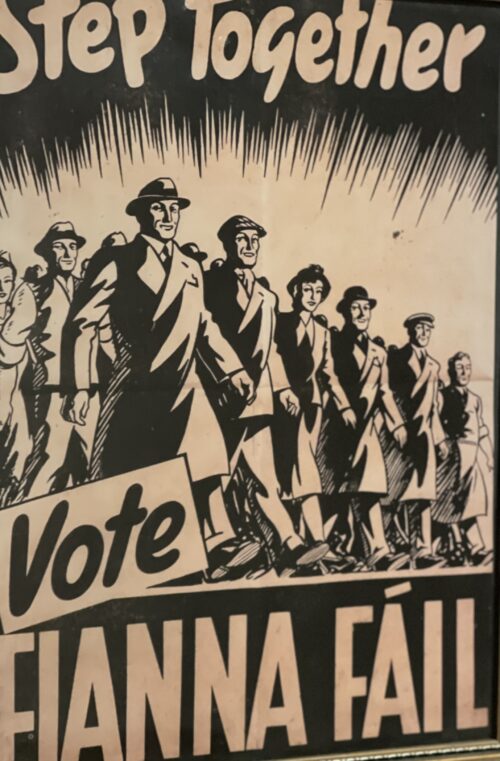

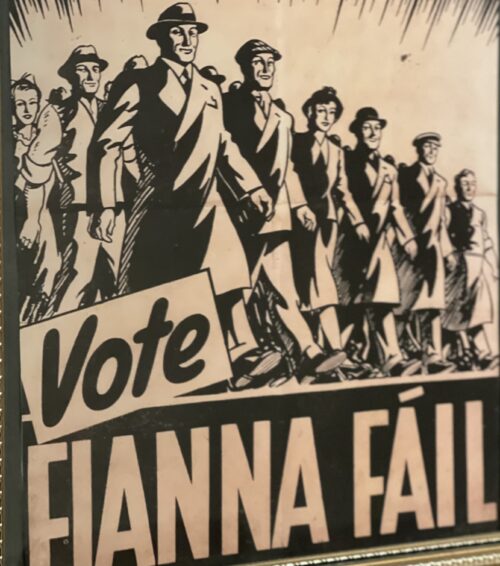

44cm x 33cm Rare post WW2 Fianna Fáil election manifesto poster -Step Together-Fianna Fail.The Republican Party was founded in 1926 by Eamon De Valera and his supporters after they split from Sinn Fein on the issue of abstentionism, in the aftermath of the Irish Civil War. Eamon de Valera, first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera;14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent statesman and political leader in 20th-century Ireland. His political career spanned over half a century, from 1917 to 1973; he served several terms as head of government and head of state. He also led the introduction of the Constitution of Ireland. Prior to de Valera's political career, he was a Commandant at Boland's Mill during the 1916 Easter Rising, an Irish revolution that would eventually contribute to Irish independence. He was arrested, sentenced to death but released for a variety of reasons, including the public response to the British execution of Rising leaders. He returned to Ireland after being jailed in England and became one of the leading political figures of the War of Independence. After the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, de Valera served as the political leader of Anti-Treaty Sinn Fein until 1926, when he, along with many supporters, left the party to set up Fianna Fáil, a new political party which abandoned the policy of abstentionism from Dáil Éireann. From there, de Valera would go on to be at the forefront of Irish politics until the turn of the 1960s. He took over as President of the Executive Councilfrom W. T. Cosgrave and later Taoiseach, with the passing of Bunreacht Na hEireann (Irish constitution) in 1937. He would serve as Taoiseach on 3 occasions; from 1937 to 1948, from 1951 to 1954 and finally from 1957 to 1959. He remains the longest serving Taoiseach by total days served in the post. He resigned in 1959 upon his election as President of Ireland. By then, he had been Leader of Fianna Fáil for 33 years, and he, along with older founding members, began to take a less prominent role relative to newer ministers such as Jack Lynch, Charles Haughey and Neil Blaney. He would serve as President from 1959 to 1973, two full terms in office. De Valera's political beliefs evolved from militant Irish republicanism to strong social, cultural and economic conservatism.He has been characterised by a stern, unbending, devious demeanor. His roles in the Civil War have also portrayed him as a divisive figure in Irish history. Biographer Tim Pat Coogan sees his time in power as being characterised by economic and cultural stagnation, while Diarmaid Ferriter argues that the stereotype of de Valera as an austere, cold and even backward figure was largely manufactured in the 1960s and is misguided. Origins: Co Clare Dimensions : 50cm x 40cm

44cm x 33cm Rare post WW2 Fianna Fáil election manifesto poster -Step Together-Fianna Fail.The Republican Party was founded in 1926 by Eamon De Valera and his supporters after they split from Sinn Fein on the issue of abstentionism, in the aftermath of the Irish Civil War. Eamon de Valera, first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera;14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent statesman and political leader in 20th-century Ireland. His political career spanned over half a century, from 1917 to 1973; he served several terms as head of government and head of state. He also led the introduction of the Constitution of Ireland. Prior to de Valera's political career, he was a Commandant at Boland's Mill during the 1916 Easter Rising, an Irish revolution that would eventually contribute to Irish independence. He was arrested, sentenced to death but released for a variety of reasons, including the public response to the British execution of Rising leaders. He returned to Ireland after being jailed in England and became one of the leading political figures of the War of Independence. After the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, de Valera served as the political leader of Anti-Treaty Sinn Fein until 1926, when he, along with many supporters, left the party to set up Fianna Fáil, a new political party which abandoned the policy of abstentionism from Dáil Éireann. From there, de Valera would go on to be at the forefront of Irish politics until the turn of the 1960s. He took over as President of the Executive Councilfrom W. T. Cosgrave and later Taoiseach, with the passing of Bunreacht Na hEireann (Irish constitution) in 1937. He would serve as Taoiseach on 3 occasions; from 1937 to 1948, from 1951 to 1954 and finally from 1957 to 1959. He remains the longest serving Taoiseach by total days served in the post. He resigned in 1959 upon his election as President of Ireland. By then, he had been Leader of Fianna Fáil for 33 years, and he, along with older founding members, began to take a less prominent role relative to newer ministers such as Jack Lynch, Charles Haughey and Neil Blaney. He would serve as President from 1959 to 1973, two full terms in office. De Valera's political beliefs evolved from militant Irish republicanism to strong social, cultural and economic conservatism.He has been characterised by a stern, unbending, devious demeanor. His roles in the Civil War have also portrayed him as a divisive figure in Irish history. Biographer Tim Pat Coogan sees his time in power as being characterised by economic and cultural stagnation, while Diarmaid Ferriter argues that the stereotype of de Valera as an austere, cold and even backward figure was largely manufactured in the 1960s and is misguided. Origins: Co Clare Dimensions : 50cm x 40cm -

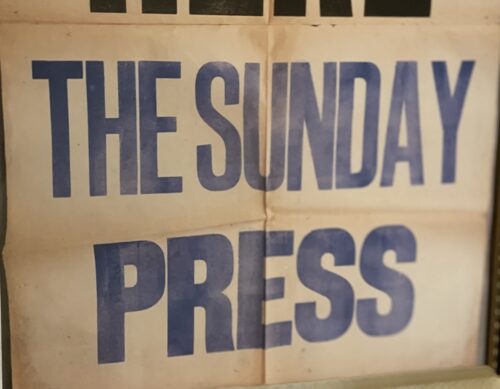

45cm x 38cm The Sunday Press was a weekly newspaper published in Ireland from 1949 until 1995. It was launched by Éamon de Valera's Irish Press group following the defeat of his Fianna Fáil party in the 1948 Irish general election. Like its sister newspaper, the daily The Irish Press, politically the paper loyally supported Fianna Fáil. The future Taoiseach Seán Lemass was the managing editor of the Irish Press who spearheaded the launch of the Sunday paper, with the first editor Colonel Matt Feehan. Many of the Irish Press journalists contributed to the paper. 'When I open the pages, I duck' was Brendan Behan's description of reading The Sunday Press, for the habit of published memoirs of veterans (usually those aligned to Fianna Fáil) of the Irish War of Independence. It soon built up a large readership, and overtook its main competitor the Sunday Independent, which tended to support Fine Gael. At its peak The Sunday Press sold up to 475,000 copies every week, and had a readership of over one million, around one third of the Irish population. Like the Evening Press, the paper's readership held up better over the years than that of the flagship title in the group, The Irish Press, and it might have survived as a stand-alone title had it been sold. However, with the collapse of the Irish Press Newspapers group in May 1995, all three titles ceased publication immediately. The launch of Ireland on Sunday in 1997 was initially interpreted by many observers as an attempt to appeal to the former readership of The Sunday Press, seen as generally rural, fairly conservative Catholic, and with a traditional Irish nationalist political outlook. When Christmas Day fell on Sunday in 1949, 1955, 1960, 1966, 1977, 1983, 1988 and 1994 the paper came out on the Saturday. Vincent Jennings at the age of 31 became editor of The Sunday Press in 1968, serving until December 1986, when he became manager of the Irish Press Group. Journalists who worked at the press include Stephen Collins served as political editor his father Willie Collins was deputy editor and Michael Carwood became sports editor of The Sunday Press in 1988 until its closure in 1995.

45cm x 38cm The Sunday Press was a weekly newspaper published in Ireland from 1949 until 1995. It was launched by Éamon de Valera's Irish Press group following the defeat of his Fianna Fáil party in the 1948 Irish general election. Like its sister newspaper, the daily The Irish Press, politically the paper loyally supported Fianna Fáil. The future Taoiseach Seán Lemass was the managing editor of the Irish Press who spearheaded the launch of the Sunday paper, with the first editor Colonel Matt Feehan. Many of the Irish Press journalists contributed to the paper. 'When I open the pages, I duck' was Brendan Behan's description of reading The Sunday Press, for the habit of published memoirs of veterans (usually those aligned to Fianna Fáil) of the Irish War of Independence. It soon built up a large readership, and overtook its main competitor the Sunday Independent, which tended to support Fine Gael. At its peak The Sunday Press sold up to 475,000 copies every week, and had a readership of over one million, around one third of the Irish population. Like the Evening Press, the paper's readership held up better over the years than that of the flagship title in the group, The Irish Press, and it might have survived as a stand-alone title had it been sold. However, with the collapse of the Irish Press Newspapers group in May 1995, all three titles ceased publication immediately. The launch of Ireland on Sunday in 1997 was initially interpreted by many observers as an attempt to appeal to the former readership of The Sunday Press, seen as generally rural, fairly conservative Catholic, and with a traditional Irish nationalist political outlook. When Christmas Day fell on Sunday in 1949, 1955, 1960, 1966, 1977, 1983, 1988 and 1994 the paper came out on the Saturday. Vincent Jennings at the age of 31 became editor of The Sunday Press in 1968, serving until December 1986, when he became manager of the Irish Press Group. Journalists who worked at the press include Stephen Collins served as political editor his father Willie Collins was deputy editor and Michael Carwood became sports editor of The Sunday Press in 1988 until its closure in 1995. -

Daly's Distillery was an Irish whiskey distillery which operated in Cork City, Ireland from around 1820 to 1869. In 1867, the distillery was purchased by the Cork Distilleries Company (CDC), in an amalgamation of five cork distilleries. Two years later, in 1869, as the smallest CDC distillery, Daly's Distillery ceased operations. In the years that followed its closure, some of the buildings became part of Shaw's Flour Mill, and Murphy's Brewery, with others continuing to be used as warehouses by Cork Distilleries Company for several years (though information is difficult to come by, their continued existence is mentioned in Alfred Barnard's 1887 account of the distilleries of the United Kingdom).

Daly's Distillery was an Irish whiskey distillery which operated in Cork City, Ireland from around 1820 to 1869. In 1867, the distillery was purchased by the Cork Distilleries Company (CDC), in an amalgamation of five cork distilleries. Two years later, in 1869, as the smallest CDC distillery, Daly's Distillery ceased operations. In the years that followed its closure, some of the buildings became part of Shaw's Flour Mill, and Murphy's Brewery, with others continuing to be used as warehouses by Cork Distilleries Company for several years (though information is difficult to come by, their continued existence is mentioned in Alfred Barnard's 1887 account of the distilleries of the United Kingdom).History

In 1798, the firm of James Daly & Co. was established as a rectifying distillery and wine merchants at a premises on Blarney St., Cork.In 1820, this was relocated to 32 John Street.As some sources state that the John distillery was established in 1807, and it is known that a William Lyons ran a distillery on John Street in the early 1800s, it is possible that Daly purchased an existing distillery on John Street. In 1822, James Daly's nephew John Murray joined the partnership.In 1828, the distillery is reported to have an output of 87,874 gallons of spirit.However, in 1833, output of only 39,000 gallons per annum was reported, which was low compared with some of the Irish distillers of the era; for instance, at that time Murphy's Distillery in nearby Midleton, had an output of over 400,000 gallons per annum. On James Daly's death, in 1850, the partnership, which at that point had consisted of James Daly, Maurice Murray (John Murray's son) and George Waters, was dissolved, with Maurice Murray taking sole ownership of the distillery, which continued to trade as James Daly & Co. After leaving the partnership, George Waters went on to purchase and run the nearby Green distillery. In 1853, Murray rebuilt and significantly extended the distillery, expanding onto neighbouring streets. By the late 1860s, the distillery had grown to occupy 3 acres, consisting of a brewhouse, distillery and maltings on John Street; granaries on Leitrim Street; and eight bonded warehouses scattered across John Street, Leitrim Street and Watercourse Road.According to accounts from the time, whiskey from the distillery, some of which was aged for seven years or more, was mainly exported "to the colonies". In particular, it was said that in Australia the whiskey sold at a premium to other whiskeys. A well respected member of the Irish distilling industry at the time, the distillery's owner Maurice Murray, conducted significant correspondence with William Ewart Gladstone, the then British Chancellor of the Exchequer, on behalf of the Irish distillers, with regard to the duties placed on Irish whiskey. In 1867, Daly's Distillery, was absorbed into Cork Distilleries Company (CDC), in an amalgamation of five Cork distilleries.As the smallest of the five distilleries, Daly's closed soon after the amalgamation, in 1869. Following its closure, Maurice Murray is known to have continued to work for the CDC at the North Mall Distillery, along with his son Daly Murray. The main distillery buildings later became part of Shaw's Flour Mill, while other buildings were incorporated into the nearby Murphy's Brewery, which was run by relatives of James Murphy of the Midleton Distillery, who was the driving force behind the establishment of the Cork Distilleries Company. One of the distillery buildings, now named "the Mill", is still visible on 32 Lower John Street, Cork. -

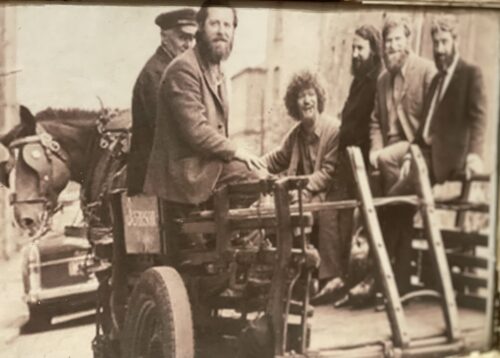

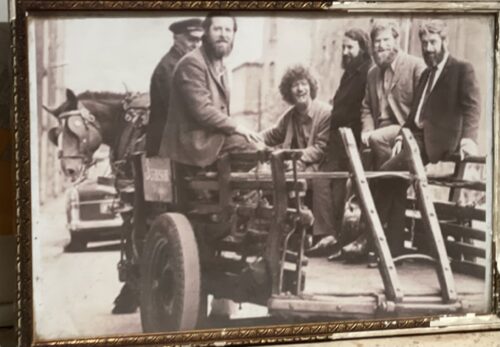

50cm x 60cm The Dubliners were quite simply one of the most famous Irish folk bands of all time.Founded in 1962,they enjoyed a 50 year career with the success of the band centred on their two lead singers,Luke Kelly and Ronnie Drew.They garnered massive international acclaim with their lively Irish folk songs,traditional street ballads and instrumentals eventually crossing over to mainstream culture by appearing on Top of the Pops in 1967 with "Seven Drunken Nights" which sold over 250000 singles in the UK alone.Later a number of collaborations with the Pogues saw them enter the UK singles charts again on another 2 occasions.Instrumental in popularising Irish folk music abroad ,they influenced many generations of Irish bands and covers of Irish ballads such as Raglan Road and the Auld Triangle by Luke Kelly and Ronnie Drew tend to be regarded as definitive versions.They also enjoyed a hard drinking and partying image as can be seen by many collaborations with alcohol advertising campaigns etc

50cm x 60cm The Dubliners were quite simply one of the most famous Irish folk bands of all time.Founded in 1962,they enjoyed a 50 year career with the success of the band centred on their two lead singers,Luke Kelly and Ronnie Drew.They garnered massive international acclaim with their lively Irish folk songs,traditional street ballads and instrumentals eventually crossing over to mainstream culture by appearing on Top of the Pops in 1967 with "Seven Drunken Nights" which sold over 250000 singles in the UK alone.Later a number of collaborations with the Pogues saw them enter the UK singles charts again on another 2 occasions.Instrumental in popularising Irish folk music abroad ,they influenced many generations of Irish bands and covers of Irish ballads such as Raglan Road and the Auld Triangle by Luke Kelly and Ronnie Drew tend to be regarded as definitive versions.They also enjoyed a hard drinking and partying image as can be seen by many collaborations with alcohol advertising campaigns etc -

48cm x 38cm Limerick In 1791 James Power, an innkeeper from Dublin, established a small distillery at his public house at 109 Thomas St., Dublin. The distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son, and had moved to a new premises at John's Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O'Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the "Big Four") came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John's Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as "about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere". At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:"The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels." The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power's Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John's Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John's Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John's Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery's pot stills were saved and now located in the college's Red Square.

48cm x 38cm Limerick In 1791 James Power, an innkeeper from Dublin, established a small distillery at his public house at 109 Thomas St., Dublin. The distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son, and had moved to a new premises at John's Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O'Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the "Big Four") came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John's Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as "about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere". At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:"The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels." The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power's Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John's Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John's Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John's Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery's pot stills were saved and now located in the college's Red Square. The Still House at John's Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

The Still House at John's Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

-

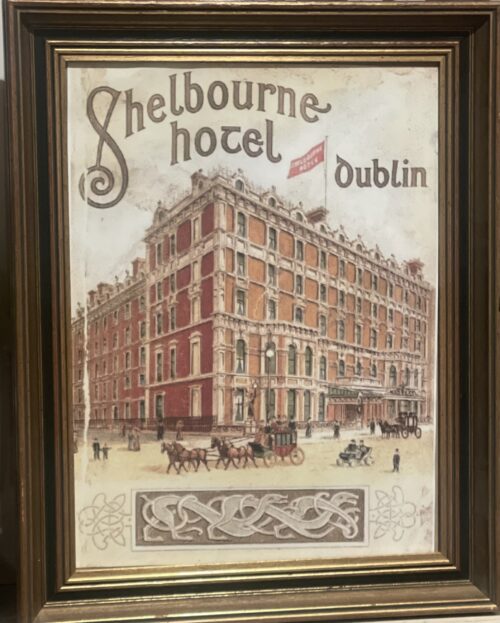

48cm x 38cm The Shelbourne Hotel is a historic hotel in Dublin, Ireland, situated in a landmark building on the north side of St Stephen's Green. Currently owned by Kennedy Wilsonand operated by Marriott International, the hotel has 265 rooms in total and reopened in March 2007 after undergoing an eighteen-month refurbishment.

48cm x 38cm The Shelbourne Hotel is a historic hotel in Dublin, Ireland, situated in a landmark building on the north side of St Stephen's Green. Currently owned by Kennedy Wilsonand operated by Marriott International, the hotel has 265 rooms in total and reopened in March 2007 after undergoing an eighteen-month refurbishment.History

The Shelbourne Hotel was founded in 1824 by Martin Burke, a native of Tipperary, when he acquired three adjoining townhousesoverlooking Stephen's Green, Europe's largest garden square. Burke named his grand new hotel The Shelbourne, after William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne. William Makepeace Thackeray was an early guest, staying in 1842 and including a piece about the Shelbourne in The Irish Sketch-Book (1843). In the early 1900s, Alois Hitler jr., the elder half-brother of Adolf Hitler, worked in the hotel while in Dublin. During the 1916 Easter Rising the hotel was occupied by 40 British troops under Captain Andrews to counter the Irish Citizen Armyand Irish Volunteer forces, commanded by Michael Mallin, who had occupied Stephen's Green. In 1922, the Constitution of the Irish Free State was drafted in room 112, now known as The Constitution Room. The facade was refurbished in 2016, winning an award from the Irish Georgian Society. In December 2018 UEFA's executive committee made the draw for the 2019 UEFA Nations League Finals in the hotel.Statues

A major redesign by John McCurdy was completed in 1867, with the Foundry of Val d'Osne casting the four external caryatid style torchère statues. These were based on two repeated beaux-arts neoclassical models originally sculpted by the prolific French sculptor Mathurin Moreau entitled Égyptienne – the two female Ancient Egyptianfigures flanking either side of the front door, and Négresse – the two female ancient Kushite (Nubian)figures flanking either corner of the main building. All four statues are wearing gold coloured anklets, and are draped, with jewellery picked out in gilt while supporting a torch with a frosted glass flambeau shade.All four statues are on a circular base with a further square metal plinth with cartouches to the angles indicating royal descent. In feint writing at the front of the circular base of all four statues can be seen the name of the foundry which produced the statues Val d'Osne. Of the several other examples of the castings, the most notable can be seen in the porch of the hôtel de ville (town hall) in the French town of Remiremont as well as outside the mausoleum of the architect Temple Hoyne Buellin Denver, Colorado and in the Jardins do Palácio de Cristal in Porto.In all three cases the door is flanked either side by one Égyptienne and one Négresse statue indicating parity. In July 2020, the statues at the front of the building were removed by management as a precautionary response to the toppling and removal of statues following the murder of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter protests. This move resulted from the belief that either two or all four of the statues represented Nubian slaves shown in manacles. Both histories of the hotel, that of 1951 by Elizabeth Bowen and that of 1999 by Michael O'Sullivan, state that two of the statues represent slaves or servants, with Bowen stating "on each stands a female statue, Nubian in aspect, holding a torch shaped lamp". Kyle Leyden, an art historian at the Courtauld Institute, argued that none of the statues are of the established "Nubian slave" type, and that all four figures wear ankletsindicating aristocratic status, rather than shackles.After an examination by Paula Murphy, an art historian at University College Dublin, concluded that the statues were not representations of slaves, it was announced that they would be restored to their plinths.After being cleaned, they were reinstalled on the night of 14 December. In James Joyce's Ulysses, Leopold Bloom remembers the Shelbourne as where "Mrs Miriam Dandrade", a "Divorced Spanish American" sold him "her old wraps and black underclothes -

48cm x 43cm The Irish Volunteers (Irish: Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force[3][4][5] or Irish Volunteer Army,was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in response to the formation of its Irish unionist/loyalist counterpart the Ulster Volunteers in 1912, and its declared primary aim was "to secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to the whole people of Ireland". The Volunteers included members of the Gaelic League, Ancient Order of Hibernians and Sinn Féin,and, secretly, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Increasing rapidly to a strength of nearly 200,000 by mid-1914, it split in September of that year over John Redmond's commitment to the British war effort, with the smaller group retaining the name of "Irish Volunteers".

48cm x 43cm The Irish Volunteers (Irish: Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force[3][4][5] or Irish Volunteer Army,was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in response to the formation of its Irish unionist/loyalist counterpart the Ulster Volunteers in 1912, and its declared primary aim was "to secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to the whole people of Ireland". The Volunteers included members of the Gaelic League, Ancient Order of Hibernians and Sinn Féin,and, secretly, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Increasing rapidly to a strength of nearly 200,000 by mid-1914, it split in September of that year over John Redmond's commitment to the British war effort, with the smaller group retaining the name of "Irish Volunteers".Formation

Home Rule for Ireland dominated political debate between the two countries since Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstoneintroduced the first Home Rule Bill in 1886, intended to grant a measure of self-government and national autonomy to Ireland, but which was rejected by the House of Commons. The second Home Rule Bill, seven years later having passed the House of Commons, was vetoed by the House of Lords. It would be the third Home Rule Bill, introduced in 1912, which would lead to the crisis in Ireland between the majority Nationalist population and the Unionists in Ulster. On 28 September 1912 at Belfast City Hall just over 450,000 Unionists signed the Ulster Covenant to resist the granting of Home Rule. This was followed in January 1913 with the formation of the Ulster Volunteers composed of adult male Unionists to oppose the passage and implementation of the bill by force of arms if necessary. The establishment of the Ulster Volunteers was (according to Eoin MacNeill) instigated, approved, and financed by English Tories with the other major British party, the Liberals, not finding "itself terribly distressed by that proceeding."Initiative

The initiative for a series of meetings leading up to the public inauguration of the Irish Volunteers came from the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).Bulmer Hobson, co-founder of the republican boy scouts, Fianna Éireann, and member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, believed the IRB should use the formation of the Ulster Volunteers as an "excuse to try to persuade the public to form an Irish volunteer force".The IRB could not move in the direction of a volunteer force themselves, as any such action by known proponents of physical force would be suppressed, despite the precedent established by the Ulster Volunteers. They therefore confined themselves to encouraging the view that nationalists also ought to organise a volunteer force for the defence of Ireland. A small committee then began to meet regularly in Dublin from July 1913, who watched the growth of this opinion. They refrained however from any action until the precedent of Ulster should have first been established while waiting for the lead to come from a "constitutional" quarter. The IRB began the preparations for the open organisation of the Irish Volunteers in January 1913. James Stritch, an IRB member, had the Irish National Foresters build a hall at the back of 41 Parnell Square in Dublin, which was the headquarters of the Wolfe Tone Clubs. Anticipating the formation of the Volunteers they began to learn foot-drill and military movements.The drilling was conducted by Stritch together with members of Fianna Éireann. They began by drilling a small number of IRB associated with the Dublin Gaelic Athletic Association, led by Harry Boland. Michael Collins along with several other IRB members claim that the formation of the Irish Volunteers was not merely a "knee-jerk reaction" to the Ulster Volunteers, which is often supposed, but was in fact the "old Irish Republican Brotherhood in fuller force.""The North Began"

The IRB knew they would need a highly regarded figure as a public front that would conceal the reality of their control. The IRB found in Eoin MacNeill, Professor of Early and Medieval History at University College Dublin, the ideal candidate. McNeill's academic credentials and reputation for integrity and political moderation had widespread appeal. The O'Rahilly, assistant editor and circulation manager of the Gaelic League newspaper An Claidheamh Soluis, encouraged MacNeill to write an article for the first issue of a new series of articles for the paper. The O'Rahilly suggested to MacNeill that it should be on some wider subject than mere Gaelic pursuits. It was this suggestion which gave rise to the article entitled The North Began, giving the Irish Volunteers its public origins. On 1 November, MacNeill's article suggesting the formation of an Irish volunteer force was published.MacNeill wrote,There is nothing to prevent the other twenty-eight counties from calling into existence citizen forces to hold Ireland "for the Empire". It was precisely with this object that the Volunteers of 1782 were enrolled, and they became the instrument of establishing Irish self-government.

After the article was published, Hobson asked The O'Rahilly to see MacNeill, to suggest to him that a conference should be called to make arrangements for publicly starting the new movement.The article "threw down the gauntlet to nationalists to follow the lead given by Ulster unionists."MacNeill was unaware of the detailed planning which was going on in the background, but was aware of Hobson's political leanings. He knew the purpose as to why he was chosen, but he was determined not to be a puppet.Launch

With MacNeill willing to take part, O'Rahilly and Hobson sent out invitations for the first meeting at Wynn's Hotel in Abbey Street, Dublin, on 11 November. Hobson himself did not attend this meeting, believing his standing as an "extreme nationalist" might prove problematical.The IRB, however, was well represented by, among others, Seán Mac Diarmada and Éamonn Ceannt, who would prove to be substantially more extreme than Hobson.Several others meetings were soon to follow, as prominent nationalists planned the formation of the Volunteers, under the leadership of MacNeill.Meanwhile, labour leaders in Dublin began calling for the establishment of a citizens' defence force in the aftermath of the lock out of 19 August 1913.Thus formed the Irish Citizen Army, led by James Larkin and James Connolly, which, though it had similar aims, at this point had no connection with the Irish Volunteers (were later allies in the Easter Rising. The Volunteer organisation was publicly launched on 25 November, with their first public meeting and enrolment rally at the Rotunda in Dublin.The IRB organised this meeting to which all parties were invited,and brought 5000 enlistment blanks for distribution and handed out in books of one hundred each to each of the stewards. Every one of the stewards and officials wore on their lapel a small silken bow the centre of which was white, while on one side was green and on the other side orange and had long been recognised as the colours which the Irish Republican Brotherhood had adopted as the Irish national banner. The hall was filled to its 4,000 person capacity, with a further 3,000 spilling onto the grounds outside. Speakers at the rally included MacNeill, Patrick Pearse, and Michael Davitt, son of the Land League founder of the same name. Over the course of the following months the movement spread throughout the country, with thousands more joining every week.Organisation and leadership

The original members of the Provisional Committee were:Portfolio Name Organisation Political Party Honorary Secretaries Eoin Mac Néill Gaelic League Laurence Kettle Ancient Order of Hibernians Irish Parliamentary Party Honorary Treasurers The O'Rahilly Gaelic League Sinn Féin John Gore Ancient Order of Hibernians Irish Parliamentary Party - Members: Piaras Béaslaí (Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB)), Sir Roger Casement (GL), Éamonn Ceannt (IRB, GL, SF), John Fitzgibbon (GL, SF), Liam Gogan, Bulmer Hobson (IRB, Fianna Éireann (FÉ)), Michael J. Judge (AOH), Thomas Kettle (IPP, AOH), James Lenehan (AOH), Michael Lonergan (IRB, Fianna Éireann (FÉ)), Peter (Peadar) Macken (IRB, Labour leader, SF, GL), Seán Mac Diarmada (IRB, Irish Freedom), Thomas MacDonagh (GL), Liam Mellows (IRB), Maurice Moore (IPP, GL, Connaught Rangers), Séamus O'Connor (IRB), Colm O'Loughlin (IRB, St. Enda's School (SES)), Peter O'Reilly (Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH)), Robert Page (IRB, Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA)), Patrick Pearse (GL, SES), Joseph M. Plunkett (GL, Irish Review), John Walsh (AOH), Peter White (Celtic Literary Society);

- Fianna Éireann representatives: Con Colbert (IRB), Eamon Martin (IRB), Patrick O'Riain (IRB).

John Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party

While the IRB was instrumental in the establishment of the Volunteers, they were never able to gain complete control of the organisation. This was compounded after John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, took an active interest. Though some well known Redmond supporters had joined the Volunteers, the attitude of Redmond and the Party was largely one of opposition, though by the Summer of 1914, it was clear the IPP needed to control the Volunteers if they were not to be a threat to their authority.The majority of the IV members, like the nation as a whole, were supporters of Redmond (though this was not necessarily true of the organisation's leadership), and, armed with this knowledge, Redmond sought IPP influence, if not outright control of the Volunteers. Negotiations between MacNeil and Redmond over the latter's future role continued inconclusively for several weeks, until on 9 June Redmond issued an ultimatum, through the press, demanding the Provisional Committee co-opt twenty-five IPP nominees.With several IPP members and their supporters on the committee already, this would give them a majority of seats, and effective control. The more moderate members of the Volunteers' Provisional Committee did not like the idea, nor the way it was presented, but they were largely prepared to go along with it to prevent Redmond from forming a rival organisation, which would draw away most of their support. The IRB was completely opposed to Redmond's demands, as this would end any chance they had of controlling the Volunteers. Hobson, who simultaneously served in leadership roles in both the IRB and the Volunteers, was one of a few IRB members to reluctantly submit to Redmond's demands, leading to a falling out with the IRB leaders, notably Tom Clarke. In the end the Committee accepted Redmond's demands, by a vote of 18 to 9, most of the votes of dissent coming from members of the IRB. The new IPP members of the committee included MP Joseph Devlin and Redmond's son William, but were mostly composed of insignificant figures, believed to have been appointed as a reward for party loyalty.[46] Despite their numbers, they were never able to exert control over the organisation, which largely remained with its earlier officers. Finances remained fully in the hands of the treasurer, The O'Rahilly, his assistant, Éamonn Ceannt, and MacNeill himself, who retained his position as chairman, further diminishing the IPP's influence.Arming the Volunteers

Shortly after the formation of the Volunteers, the British Parliament banned the importation of weapons into Ireland. The "Curragh incident" (also referred to as the "Curragh Mutiny") of March 1914, indicated that the government could not rely on its army to ensure a smooth transition to Home Rule.Then in April 1914 the Ulster Volunteerssuccessfully imported 24,000 rifles in the Larne Gun Running event. The Irish Volunteers realised that it too would have to follow suit if they were to be taken as a serious force. Indeed, many contemporary observers commented on the irony of "loyal" Ulstermen arming themselves and threatening to defy the British government by force. Patrick Pearsefamously replied that "the Orangeman with a gun is not as laughable as the nationalist without one." Thus O'Rahilly, Sir Roger Casement and Bulmer Hobson worked together to co-ordinate a daylight gun-running expedition to Howth, just north of Dublin. The plan worked, and Erskine Childers brought nearly 1,000 rifles, purchased from Germany, to the harbour on 26 July and distributed them to the waiting Volunteers, without interference from the authorities. The remainder of the guns smuggled from Germany for the Irish Volunteers were landed at Kilcoole a week later by Sir Thomas Myles. As the Volunteers marched from Howth back to Dublin, however, they were met by a large patrol of the Dublin Metropolitan Police and the King's Own Scottish Borderers. The Volunteers escaped largely unscathed, but when the Borderers returned to Dublin they clashed with a group of unarmed civilians who had been heckling them at Bachelors Walk. Though no order was given, the soldiers fired on the civilians, killing four and further wounding 37. This enraged the populace, and during the outcry enlistments in the Volunteers soared.The Split

The outbreak of World War I in August 1914 provoked a serious split in the organisation. Redmond, in the interest of ensuring the enactment of the Home Rule Act 1914 then on the statute books, encouraged the Volunteers to support the British and Allied war commitment and join Irish regiments of the British New Army divisions, an action which angered the founding members. Given the wide expectation that the war was going to be a short one, the majority however supported the war effort and the call to restore the "freedom of small nations" on the European continent. They left to form the National Volunteers, some of whose members fought in the 10th and 16th (Irish) Division, side by side with their Ulster Volunteer counterparts from the 36th (Ulster) Division. A minority believed that the principles used to justify the Allied war cause were best applied in restoring the freedom to one small country in particular. They retained the name "Irish Volunteers", were led by MacNeill and called for Irish neutrality. The National Volunteers kept some 175,000 members, leaving the Irish Volunteers with an estimated 13,500. However, the National Volunteers declined rapidly, and the few remaining members reunited with the Irish Volunteers in October 1917.The split proved advantageous to the IRB, which was now back in a position to control the organisation. Following the split, the remnants of the Irish Volunteers were often, and erroneously, referred to as the "Sinn Féin Volunteers", or, by the British press, derisively as "Shinners", after Arthur Griffith's political organisation Sinn Féin. Although the two organisations had some overlapping membership, there was no official connection between Griffith's then moderate Sinn Féin and the Volunteers. The political stance of the remaining Volunteers was not always popular, and a 1,000-strong march led by Pearse through the garrison city of Limerick on Whit Sunday, 1915, was pelted with rubbish by a hostile crowd. Pearse explained the reason for the establishment of the new force when he said in May 1915:What if conscription be enforced on Ireland? What if a Unionist or a Coalition British Ministry repudiates the Home Rule Act? What if it be determined to dismember Ireland? The future is big with these and other possibilities.

After the departure of Redmond and his followers, the Volunteers adopted a constitution, which had been drawn up by the earlier provisional committee, and was ratified by a convention of 160 delegates on 25 October 1914. It called for general council of fifty members to meet monthly, as well as an executive of the president and eight elected members. In December a headquarters staff was appointed, consisting of Eoin MacNeill as chief of staff, The O'Rahilly as director of arms, Thomas MacDonagh as director of training, Patrick Pearse as director of military organisation, Bulmer Hobson as quartermaster, and Joseph Plunkett as director of military operations. The following year they were joined by Éamonn Ceannt as director of communications and J.J. O'Connell as chief of inspection. This reorganisation put the IRB is a stronger position, as four important military positions (director of training, director of military organisation, director of military operations, and director of communications) were held by men who were, or would soon be, members of the IRB, and who later become four of the seven signatories of the Easter Proclamation. (Hobson was also an IRB member, but had a falling out with the leadership after he supported Redmond's appointees to the provisional council, and hence played little role in the IRB thereafter.)Easter Rising, 1916

The official stance of the Irish Volunteers was that action would only be taken were the British authorities at Dublin Castle to attempt to disarm the Volunteers, arrest their leaders, or introduce conscription to Ireland.The IRB, however, was determined to use the Volunteers for offensive action while Britain was tied up in the First World War. Their plan was to circumvent MacNeill's command, instigating a Rising, and to get MacNeill on board once the rising was a fait accompli. Pearse issued orders for three days of parades and manoeuvres, a thinly disguised order for a general insurrection.MacNeill soon discovered the real intent behind the orders and attempted to stop all actions by the Volunteers. He succeeded only in putting the Rising off for a day, and limiting it to about 1,000 active participants within Dublin and a very limited action elsewhere. Almost all of the fighting was confined to Dublin - though the Volunteers were involved in engagements against RIC barracks in Ashbourne, County Meath, and there were actions in Enniscorthy, County Wexford and in County Galway.The Irish Citizen Army supplied slightly more than 200 personnel for the Dublin campaign.Reorganisation

Steps towards reorganising the Irish Volunteers were taken during 1917, and on 27 October 1917 a convention was held in Dublin. This convention was called to coincide with the Sinn Féin party conference. Nearly 250 people attended the convention; internment prevented many more from attending. The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) estimated that 162 companies of volunteers were active in the country, although other sources suggest a figure of 390. The proceedings were presided over by Éamon de Valera, who had been elected President of Sinn Féin the previous day. Also on the platform were Cathal Brugha and many others who were prominent in the reorganising of the Volunteers in the previous few months, many of them ex-prisoners. De Valera was elected president. A national executive was also elected, composed of representatives of all parts of the country. In addition, a number of directors were elected to head the various IRA departments. Those elected were: Michael Collins (Director for Organisation); Richard Mulcahy (Director of Training); Diarmuid Lynch (Director for Communications); Michael Staines (Director for Supply); Rory O'Connor (Director of Engineering). Seán McGarry was voted general secretary, while Cathal Brugha was made Chairman of the Resident Executive, which in effect made him Chief of Staff. The other elected members were: M. W. O'Reilly (Dublin); Austin Stack (Kerry); Con Collins (Limerick); Seán MacEntee (Belfast); Joseph O'Doherty (Donegal); Paul Galligan(Cavan); Eoin O'Duffy (Monaghan); Séamus Doyle (Wexford); Peadar Bracken (Offaly); Larry Lardner (Galway); Richard Walsh (Mayo) and another member from Connacht. There were six co-options to make-up the full number when the directors were named from within their ranks. The six were all Dublin men: Eamonn Duggan; Gearóid O'Sullivan; Fintan Murphy; Diarmuid O'Hegarty; Dick McKee and Paddy Ryan. Of the 26 elected, six were also members of the Sinn Féin National Executive, with Éamon de Valera president of both. Eleven of the 26 were elected Teachta Dála (members of the Dáil) in the 1918 general election and 13 in the May 1921 election.Relationship with Dáil Éireann