-

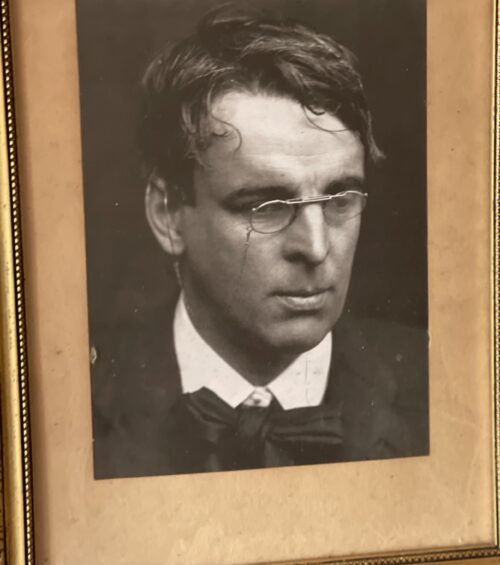

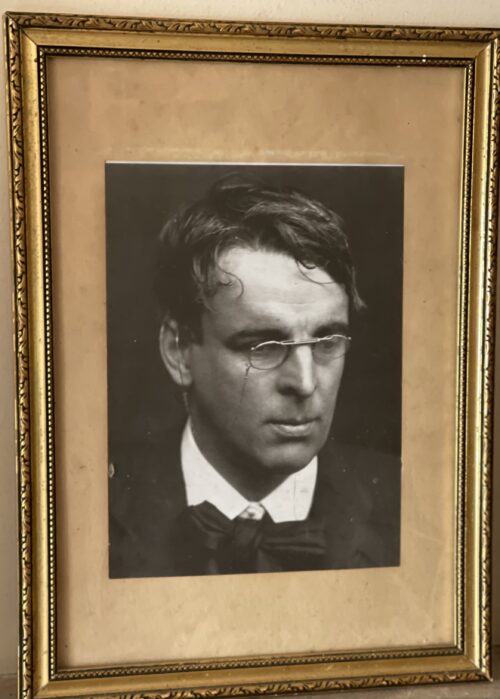

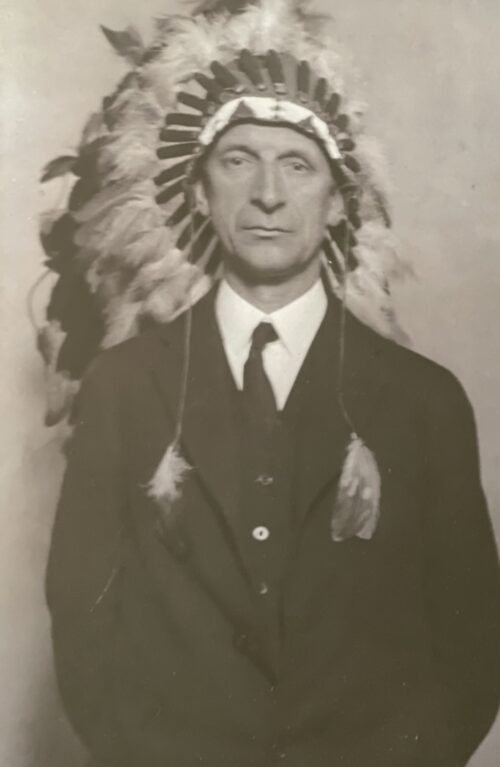

40cm x 30cm Enniscrone Co Sligo William Butler Yeats(13 June 1865 – 28 January 1939) Irish poet, dramatist, prose writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. A pillar of the Irish literary establishment, he helped to found the Abbey Theatre, and in his later years served two terms as a Senator of the Irish Free State. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival along with Lady Gregory, Edward Martyn and others. Yeats was born in Sandymount, Ireland, and educated there and in London. He was a Protestant and member of the Anglo-Irish community. He spent childhood holidays in County Sligo and studied poetry from an early age, when he became fascinated by Irish legends and the occult. These topics feature in the first phase of his work, which lasted roughly until the turn of the 20th century. His earliest volume of verse was published in 1889, and its slow-paced and lyrical poems display debts to Edmund Spenser, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the poets of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. From 1900, his poetry grew more physical and realistic. He largely renounced the transcendental beliefs of his youth, though he remained preoccupied with physical and spiritual masks, as well as with cyclical theories of life. In 1923, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

40cm x 30cm Enniscrone Co Sligo William Butler Yeats(13 June 1865 – 28 January 1939) Irish poet, dramatist, prose writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. A pillar of the Irish literary establishment, he helped to found the Abbey Theatre, and in his later years served two terms as a Senator of the Irish Free State. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival along with Lady Gregory, Edward Martyn and others. Yeats was born in Sandymount, Ireland, and educated there and in London. He was a Protestant and member of the Anglo-Irish community. He spent childhood holidays in County Sligo and studied poetry from an early age, when he became fascinated by Irish legends and the occult. These topics feature in the first phase of his work, which lasted roughly until the turn of the 20th century. His earliest volume of verse was published in 1889, and its slow-paced and lyrical poems display debts to Edmund Spenser, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the poets of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. From 1900, his poetry grew more physical and realistic. He largely renounced the transcendental beliefs of his youth, though he remained preoccupied with physical and spiritual masks, as well as with cyclical theories of life. In 1923, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. -

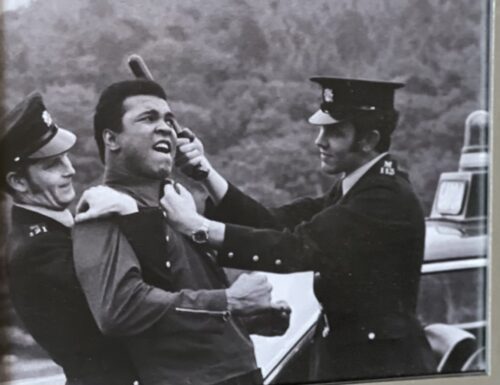

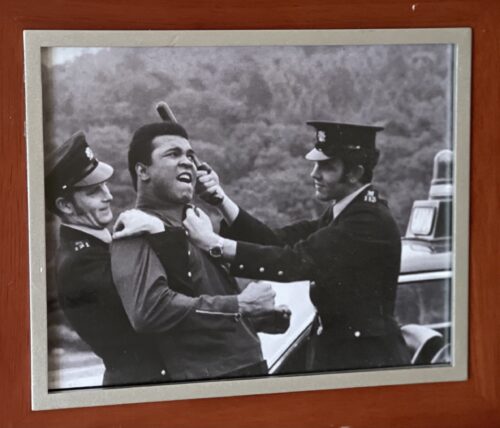

29cm x 36cm. Dublin Famous picture during The Greatest's visit to Ireland of Muhammad Ali play fighting with two members of An Garda Siochana.Some memory for those officers to tell their grandchildren about ! July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.

29cm x 36cm. Dublin Famous picture during The Greatest's visit to Ireland of Muhammad Ali play fighting with two members of An Garda Siochana.Some memory for those officers to tell their grandchildren about ! July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.Muhammad Ali's Irish roots explained

The astonishing fact that he had Irish roots, being descended from Abe Grady, an Irishman from Ennis, County Clare, only became known later in life. He returned to Ireland where he had fought and defeated Al “Blue” Lewis in Croke Park in 1972 almost seven years ago in 2009 to help raise money for his non–profit Muhammad Ali Center, a cultural and educational center in Louisville, Kentucky, and other hospices. He was also there to become the first Freeman of the town. The boxing great is no stranger to Irish shores and previously made a famous trip to Ireland in 1972 when he sat down with Cathal O’Shannon of RTE for a fascinating television interview. What’s more, genealogist Antoinette O'Brien discovered that one of Ali’s great-grandfathers emigrated to the United States from County Clare, meaning that the three-time heavyweight world champion joins the likes of President Obama and Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. as prominent African-Americans with Irish heritage. In the 1860s, Abe Grady left Ennis in County Clare to start a new life in America. He would make his home in Kentucky and marry a free African-American woman. The couple started a family, and one of their daughters was Odessa Lee Grady. Odessa met and married Cassius Clay, Sr. and on January 17, 1942, Cassius junior was born. Cassius Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali when he became a Muslim in 1964. Ali, an Olympic gold medalist at the 1960 games in Rome, has been suffering from Parkinson's for some years but was committed to raising funds for his center During his visit to Clare, he was mobbed by tens of thousands of locals who turned out to meet him and show him the area where his great-grandfather came from.Tracing Muhammad Ali's roots back to County Clare

Historian Dick Eastman had traced Ali’s roots back to Abe Grady the Clare emigrant to Kentucky and the freed slave he married. Eastman wrote: “An 1855 land survey of Ennis, a town in County Clare, Ireland, contains a reference to John Grady, who was renting a house in Turnpike Road in the center of the town. His rent payment was fifteen shillings a month. A few years later, his son Abe Grady immigrated to the United States. He settled in Kentucky." Also, around the year 1855, a man and a woman who were both freed slaves, originally from Liberia, purchased land in or around Duck Lick Creek, Logan, Kentucky. The two married, raised a family and farmed the land. These free blacks went by the name, Morehead, the name of white slave owners of the area. Odessa Grady Clay, Cassius Clay's mother, was the great-granddaughter of the freed slave Tom Morehead and of John Grady of Ennis, whose son Abe had emigrated from Ireland to the United States. She named her son Cassius in honor of a famous Kentucky abolitionist of that time. When he changed his name to Muhammad Ali in 1964, the famous boxer remarked, "Why should I keep my white slavemaster name visible and my black ancestors invisible, unknown, unhonored?" Ali was not only the greatest sporting figure, but he was also the best-known person in the world at his height, revered from Africa to Asia and all over the world. To the end, he was a battler, shown rare courage fighting Parkinson’s Disease, and surviving far longer than most sufferers from the disease. -

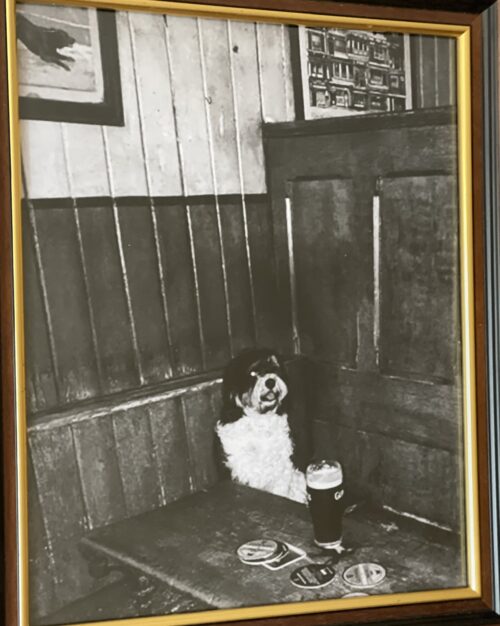

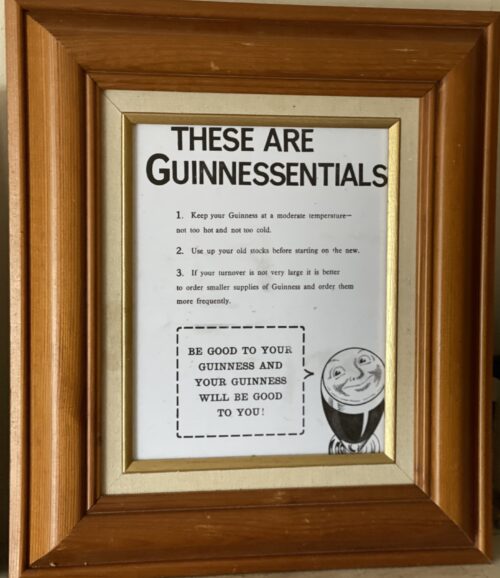

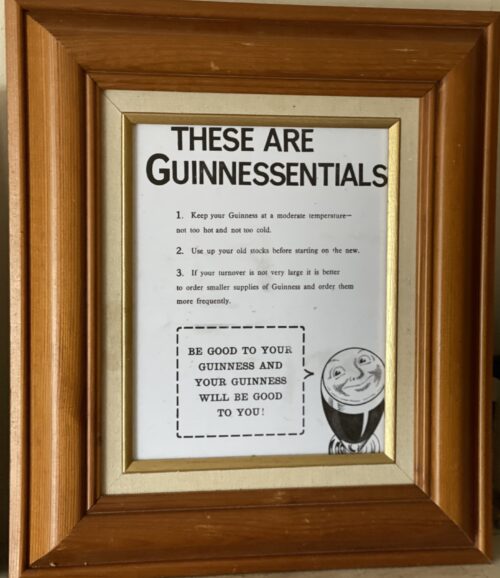

Framed Guinness ephemera -these are Guinnessentials- a guide to publicans selling the Black Stuff ! Dimensions : 43cm x 36cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm

Framed Guinness ephemera -these are Guinnessentials- a guide to publicans selling the Black Stuff ! Dimensions : 43cm x 36cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm -

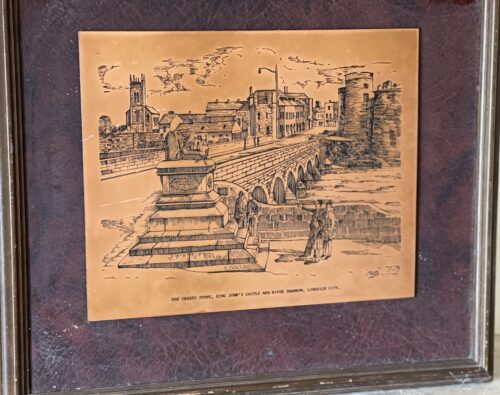

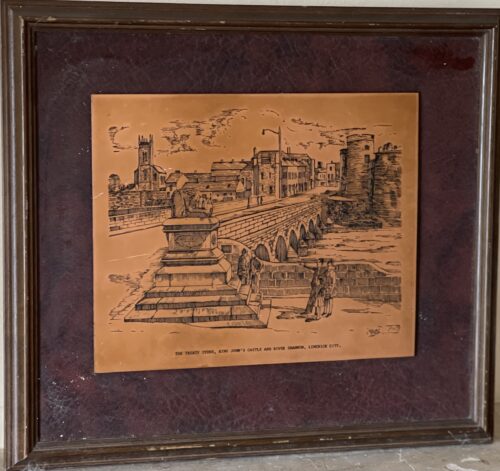

34cm x 39cm Limerick CityThe Treaty Stone is the rock that the Treaty of Limerick was signed in 1691, marking the surrender of the city to William of Orange.King John's Castle is a 13th-century castle located on King's Island in Limerick, Ireland, next to the River Shannon.Although the site dates back to 922 when the Vikings lived on the Island, the castle itself was built on the orders of King John in 1200. One of the best preserved Norman castles in Europe, the walls, towers and fortifications remain today and are visitor attractions. The remains of a Viking settlement were uncovered during archaeological excavations at the site in 1900. Thomondgate was part of the “Northern” Liberties granted to Limerick in 1216. This area was the border between Munster and Connacht until County Clare, which was created in 1565, was annexed by Munster in 1602. TheThomondgate bridge was originally built in 1185 on the orders of King John and is said to have cost the hefty sum of £30. As a result of poor workmanship the bridge collapsed in 1292 causing the deaths of 80 people. Soon after, the bridge was rebuilt with the addition of two gate towers, one at each end. It partially collapsed in 1833 as a result of bad weather and was replaced with a bridge designed by brothers James and George Pain at a cost of £10,000.Limerick is known as the Treaty City, so called after the Treaty of Limerick signed on the 3rd of October 1691 after the war between William III of England (known as William of Orange) and his Father in Law King James II. Limericks role in the successful accession of William of Orange and his wife Mary Stuart, daughter of King James II to the throne of England cannot be understated. The Treaty, according to tradition was signed on a stone in the sight of both armies at the Clare end of Thomond Bridge on the 3rd of October 1691. The stone was for some years resting on the ground opposite its present location, where the old Ennis mail coach left to travel from the Clare end of Thomond Bridge, through Cratloe woods en route to Ennis. The Treaty stone of Limerick has rested on a plinth since 1865, at the Clare end of Thomond Bridge. The pedestal was erected in May 1865 by John Richard Tinsley, mayor of the city.

34cm x 39cm Limerick CityThe Treaty Stone is the rock that the Treaty of Limerick was signed in 1691, marking the surrender of the city to William of Orange.King John's Castle is a 13th-century castle located on King's Island in Limerick, Ireland, next to the River Shannon.Although the site dates back to 922 when the Vikings lived on the Island, the castle itself was built on the orders of King John in 1200. One of the best preserved Norman castles in Europe, the walls, towers and fortifications remain today and are visitor attractions. The remains of a Viking settlement were uncovered during archaeological excavations at the site in 1900. Thomondgate was part of the “Northern” Liberties granted to Limerick in 1216. This area was the border between Munster and Connacht until County Clare, which was created in 1565, was annexed by Munster in 1602. TheThomondgate bridge was originally built in 1185 on the orders of King John and is said to have cost the hefty sum of £30. As a result of poor workmanship the bridge collapsed in 1292 causing the deaths of 80 people. Soon after, the bridge was rebuilt with the addition of two gate towers, one at each end. It partially collapsed in 1833 as a result of bad weather and was replaced with a bridge designed by brothers James and George Pain at a cost of £10,000.Limerick is known as the Treaty City, so called after the Treaty of Limerick signed on the 3rd of October 1691 after the war between William III of England (known as William of Orange) and his Father in Law King James II. Limericks role in the successful accession of William of Orange and his wife Mary Stuart, daughter of King James II to the throne of England cannot be understated. The Treaty, according to tradition was signed on a stone in the sight of both armies at the Clare end of Thomond Bridge on the 3rd of October 1691. The stone was for some years resting on the ground opposite its present location, where the old Ennis mail coach left to travel from the Clare end of Thomond Bridge, through Cratloe woods en route to Ennis. The Treaty stone of Limerick has rested on a plinth since 1865, at the Clare end of Thomond Bridge. The pedestal was erected in May 1865 by John Richard Tinsley, mayor of the city. -

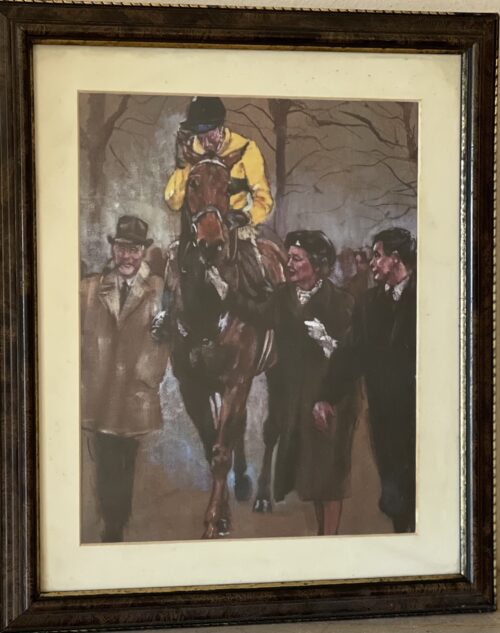

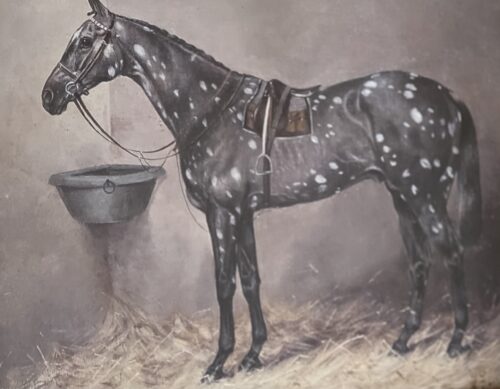

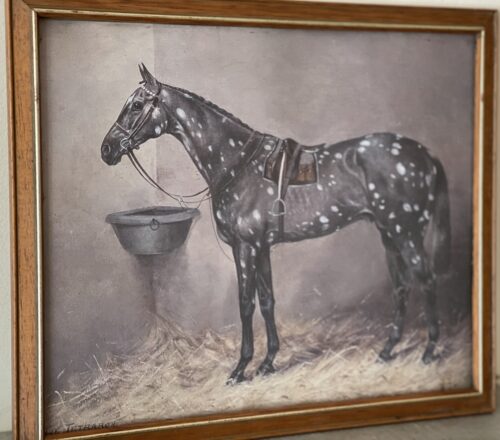

45cm x 35cm Naas Co Kildare Arkle (19 April 1957 – 31 May 1970) was an Irish Thoroughbred racehorse. A bay gelding by Archive out of Bright Cherry, he was the grandson of the unbeaten (in 14 races) flat racehorse and prepotent sire Nearco. Arkle was born at Ballymacoll Stud, County Meath, by Mrs Mary Alison Baker of Malahow House, near Naul, County Dublin. He was named after the mountain Arkle in Sutherland, Scotland that bordered the Duchess of Westminster’s Sutherland estate. Owned by Anne Grosvenor, Duchess of Westminster, he was trained by Tom Dreaper at Greenogue, Kilsallaghan in County Meath, Ireland, and ridden during his steeplechasing career by Pat Taaffe. At 212, his Timeform rating is the highest ever awarded to a steeplechaser. Only Flyingbolt, also trained by Dreaper, had a rating anywhere near his at 210. Next on their ratings are Sprinter Sacre on 192 and then Kauto Star and Mill House on 191. Despite his career being cut short by injury, Arkle won three Cheltenham Gold Cups, the Blue Riband of steeplechasing, and a host of other top prizes. On 19th April, 2014 a magnificent 1.1 scale bronze statue was unveiled in Ashbourne, County Meath in commemoration of Arkle. In the 1964 Cheltenham Gold Cup, Arkle beat Mill House (who had won the race the previous year) by five lengths to claim his first Gold Cup at odds of 7/4. It was the last time he did not start as the favourite for a race. Only two other horses entered the Gold Cup that year. The racing authorities in Ireland took the unprecedented step in the Irish Grand National of devising two weight systems — one to be used when Arkle was running and one when he was not. Arkle won the 1964 race by only one length, but he carried two and half stones more than his rivals. The following year's Gold Cup saw Arkle beat Mill House by twenty lengths at odds of 3/10. In the 1966 renewal, he was the shortest-priced favourite in history to win the Gold Cup, starting at odds of 1/10. He won the race by thirty lengths despite a mistake early in the race where he ploughed through a fence. However, it did not stop his momentum, nor did he ever look like falling. Arkle had a strange quirk in that he crossed his forelegs when jumping a fence. He went through the season 1965/66 unbeaten in five races. Arkle won 27 of his 35 starts and won at distances from 1m 6f up to 3m 5f. Legendary Racing commentator Peter O'Sullevan has called Arkle a freak of nature — something unlikely to be seen again. Besides winning three consecutive Cheltenham Gold Cups (1964, 1965, 1966) and the 1965 King George VI Chase, Arkle triumphed in a number of other important handicap chases, including the 1964 Irish Grand National (under 12-0), the 1964 and 1965 Hennessy Gold Cups (both times under 12-7), the 1965 Gallagher Gold Cup (conceding 16 lb to Mill House while breaking the course record by 17 seconds), and the 1965 Whitbread Gold Cup(under 12-7). In the 1966 Hennessy, he failed by only half a length to give Stalbridge Colonist 35 lb. The scale of the task Arkle faced is shown by the winner coming second and third in the two following Cheltenham Gold Cups, while in third place was the future 1969 Gold Cup winner, What A Myth. In December 1966, Arkle raced in the King George VI Chase at Kempton Park but struck the guard rail with a hoof when jumping the open ditch, which resulted in a fractured pedal bone; despite this injury, he completed the race and finished second. He was in plaster for four months and, though he made a good enough recovery to go back into training, he never ran again. He was retired and ridden as a hack by his owner and then succumbed to what has been variously described as advanced arthritis or possibly brucellosis and was put down at the early age of 13. Arkle became a national legend in Ireland. His strength was jokingly claimed to come from drinking 2 pints of Guinness a day. At one point, the slogan Arkle for President was written on a wall in Dublin. The horse was often referred to simply as "Himself", and he supposedly received items of fan mail addressed to 'Himself, Ireland'. The Irish government-owned Irish National Stud, at Tully, Kildare, Co. Kildare, Ireland, has the skeleton of Arkle on display in its museum. A statue in his memory was erected in Ashbourne Co. Meath in April 2014.

45cm x 35cm Naas Co Kildare Arkle (19 April 1957 – 31 May 1970) was an Irish Thoroughbred racehorse. A bay gelding by Archive out of Bright Cherry, he was the grandson of the unbeaten (in 14 races) flat racehorse and prepotent sire Nearco. Arkle was born at Ballymacoll Stud, County Meath, by Mrs Mary Alison Baker of Malahow House, near Naul, County Dublin. He was named after the mountain Arkle in Sutherland, Scotland that bordered the Duchess of Westminster’s Sutherland estate. Owned by Anne Grosvenor, Duchess of Westminster, he was trained by Tom Dreaper at Greenogue, Kilsallaghan in County Meath, Ireland, and ridden during his steeplechasing career by Pat Taaffe. At 212, his Timeform rating is the highest ever awarded to a steeplechaser. Only Flyingbolt, also trained by Dreaper, had a rating anywhere near his at 210. Next on their ratings are Sprinter Sacre on 192 and then Kauto Star and Mill House on 191. Despite his career being cut short by injury, Arkle won three Cheltenham Gold Cups, the Blue Riband of steeplechasing, and a host of other top prizes. On 19th April, 2014 a magnificent 1.1 scale bronze statue was unveiled in Ashbourne, County Meath in commemoration of Arkle. In the 1964 Cheltenham Gold Cup, Arkle beat Mill House (who had won the race the previous year) by five lengths to claim his first Gold Cup at odds of 7/4. It was the last time he did not start as the favourite for a race. Only two other horses entered the Gold Cup that year. The racing authorities in Ireland took the unprecedented step in the Irish Grand National of devising two weight systems — one to be used when Arkle was running and one when he was not. Arkle won the 1964 race by only one length, but he carried two and half stones more than his rivals. The following year's Gold Cup saw Arkle beat Mill House by twenty lengths at odds of 3/10. In the 1966 renewal, he was the shortest-priced favourite in history to win the Gold Cup, starting at odds of 1/10. He won the race by thirty lengths despite a mistake early in the race where he ploughed through a fence. However, it did not stop his momentum, nor did he ever look like falling. Arkle had a strange quirk in that he crossed his forelegs when jumping a fence. He went through the season 1965/66 unbeaten in five races. Arkle won 27 of his 35 starts and won at distances from 1m 6f up to 3m 5f. Legendary Racing commentator Peter O'Sullevan has called Arkle a freak of nature — something unlikely to be seen again. Besides winning three consecutive Cheltenham Gold Cups (1964, 1965, 1966) and the 1965 King George VI Chase, Arkle triumphed in a number of other important handicap chases, including the 1964 Irish Grand National (under 12-0), the 1964 and 1965 Hennessy Gold Cups (both times under 12-7), the 1965 Gallagher Gold Cup (conceding 16 lb to Mill House while breaking the course record by 17 seconds), and the 1965 Whitbread Gold Cup(under 12-7). In the 1966 Hennessy, he failed by only half a length to give Stalbridge Colonist 35 lb. The scale of the task Arkle faced is shown by the winner coming second and third in the two following Cheltenham Gold Cups, while in third place was the future 1969 Gold Cup winner, What A Myth. In December 1966, Arkle raced in the King George VI Chase at Kempton Park but struck the guard rail with a hoof when jumping the open ditch, which resulted in a fractured pedal bone; despite this injury, he completed the race and finished second. He was in plaster for four months and, though he made a good enough recovery to go back into training, he never ran again. He was retired and ridden as a hack by his owner and then succumbed to what has been variously described as advanced arthritis or possibly brucellosis and was put down at the early age of 13. Arkle became a national legend in Ireland. His strength was jokingly claimed to come from drinking 2 pints of Guinness a day. At one point, the slogan Arkle for President was written on a wall in Dublin. The horse was often referred to simply as "Himself", and he supposedly received items of fan mail addressed to 'Himself, Ireland'. The Irish government-owned Irish National Stud, at Tully, Kildare, Co. Kildare, Ireland, has the skeleton of Arkle on display in its museum. A statue in his memory was erected in Ashbourne Co. Meath in April 2014. -

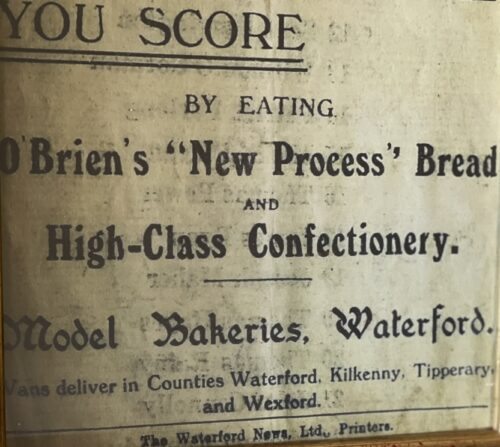

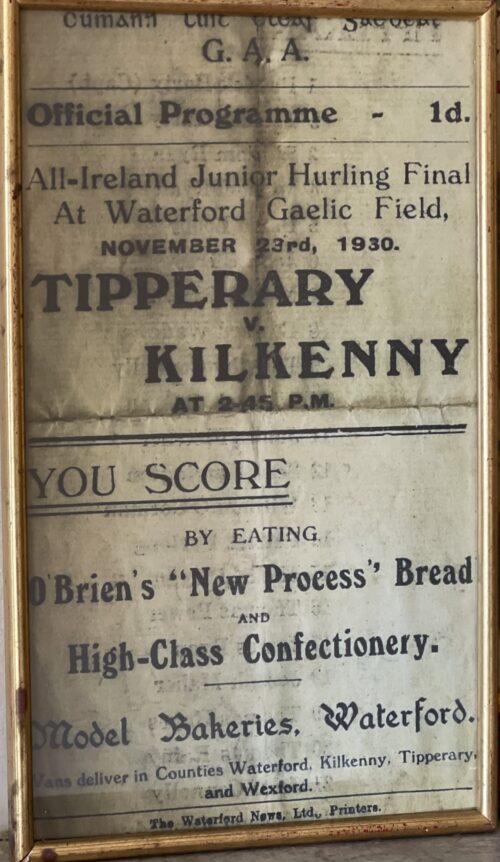

40cm x 23cm Thurles Co Tipperary The All-Ireland Junior Hurling Championship was a hurling competition organized by the Gaelic Athletic Association in Ireland. The competition was originally contested by the second teams of the strong counties, and the first teams of the weaker counties. In the years from 1961 to 1973 and from 1997 until now, the strong counties have competed for the All-Ireland Intermediate Hurling Championship instead. The competition was then restricted to the weaker counties. The competition was discontinued after 2004 as these counties now compete for the Nicky Rackard Cup instead. From 1974 to 1982, the original format of the competition was abandoned, and the competition was incorporated in Division 3 of the National Hurling League. The original format, including the strong hurling counties was re-introduced in 1983. 1930 – TIPPERARY: Paddy Harty (Captain), Tom Harty, Willie Ryan, Tim Connolly, Mick McGann, Martin Browne, Ned Wade, Tom Ryan, Jack Dwyer, Mick Ryan, Dan Looby, Pat Furlong, Bill O’Gorman, Joe Fletcher, Sean Harrington.

40cm x 23cm Thurles Co Tipperary The All-Ireland Junior Hurling Championship was a hurling competition organized by the Gaelic Athletic Association in Ireland. The competition was originally contested by the second teams of the strong counties, and the first teams of the weaker counties. In the years from 1961 to 1973 and from 1997 until now, the strong counties have competed for the All-Ireland Intermediate Hurling Championship instead. The competition was then restricted to the weaker counties. The competition was discontinued after 2004 as these counties now compete for the Nicky Rackard Cup instead. From 1974 to 1982, the original format of the competition was abandoned, and the competition was incorporated in Division 3 of the National Hurling League. The original format, including the strong hurling counties was re-introduced in 1983. 1930 – TIPPERARY: Paddy Harty (Captain), Tom Harty, Willie Ryan, Tim Connolly, Mick McGann, Martin Browne, Ned Wade, Tom Ryan, Jack Dwyer, Mick Ryan, Dan Looby, Pat Furlong, Bill O’Gorman, Joe Fletcher, Sean Harrington. -

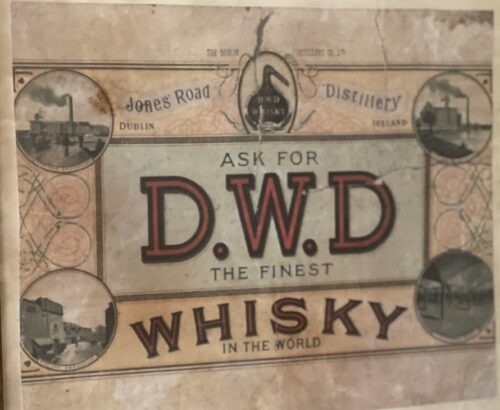

Vintage D.W.D Pot Still Whiskey Framed Advert 27cm x 35cm Granard Co Longford

Vintage D.W.D Pot Still Whiskey Framed Advert 27cm x 35cm Granard Co LongfordHistory of the DWD Whiskey Distillery

The Dublin Whiskey Distillery Co Rebirth & Redemption

Ireland’s history of whiskey distilling runs long and deep. The word ‘whiskey’ comes from the Gaelic, “uisce beatha”, meaning “water of life”, and Irish whiskey is one of the earliest known distilled beverages in the world, believed to have originated when Irish monks brought the technique of distilling perfumes back to Ireland around 1000 AD. Ever resourceful, the Irish modified this craft to create the wonderful spirit that endures to this day. But Irish whiskey’s most recent past reveals an extraordinary tale of subterfuge and intrigue that belies this golden spirit. The mercurial craft of whiskey making has lost none of its ethereal mystique and remains indelibly woven with what it means to be Irish. It has oiled a rich and eclectic culture that has reached far beyond our island shores. Yet the ‘light music’ appreciated by Joyce hides a dramatic tale of endurance and fortitude that has demanded so much from its leading protagonists. Neither war, nor famine or draconian law, be it home-grown or foreign made, or the shifting sands of empires and nations, or the shallow trends of libatious fashion could halt this most resolute and enduring spirit.

The founder and Master Distiller of the Dublin Whiskey Distillery Company

John Brannick, founder and master distiller of the Dublin Whiskey Distillery Company, was born into a renowned family of Irish whiskey-makers. His father Patrick and his uncles were all established distillers with Sir John Power of “Powers Irish Whiskey” fame, and in time both John and his younger brother Patrick Jr would follow in their father’s footsteps. Like all the great Irish distillers of the 19th century, the Brannick family used traditional “Pot Still” distillation, the simplest and oldest form of distillation, the principles of which have remained unchanged to this day. First, a whiskey “mash” comprised of water and grain is prepared. Yeast is added, causing fermentation, which creates alcohol in a solution known as “distiller’s beer” or “wash”. The “wash” is placed into a round bottomed copper kettle or “Pot Still” and heated to a temperature above the boiling point of alcohol but below that of water. The alcohol evaporates, leaving the water behind, and the vapour rises into a tube where it cools and condenses back into spirit. However, not all spirit is created equal. The early evaporations and the last evaporations, known as “heads” and “tails,” contain impurities, so it is the “heart” or mid part of the distillation process that the distiller seeks. The essence of distillation is timing, knowing when to “cut” between the head, heart and tail and retain only the best spirit. It was this time-honoured process that the young John Brannick learned from his father and uncles, a method to which he faithfully adhered and a skill which he perfected throughout his life. 1845 was a significant year for John Brannick when, at the age of 15, he began his formal apprenticeship at the John’s Lane Distillery. The Powers Distillery was one of the great distilleries of Dublin and young John’s experiences there instilled in him a lifelong passion for the fine art of whiskey-making. At the time, Ireland was an impoverished country with little or no industry. Distilleries constituted a rare exception and they, their owners and employees enjoyed significant status in their communities. The young John Brannick soon demonstrated a natural flair for the craft of whiskey-making. These early years, working within the hallowed halls of the John’s Lane Distillery, laid the foundations for his later exploits within the industry. It wasn’t long before the other great distilleries took note of his growing reputation and in 1852 George Roe & Sons enticed Brannick to join the House of George Roe & Co with the promise that he would some day become a Master Distiller.After nearly 20 years of perfecting his craft with the House of Roe, Brannick had reached the illustrious position of Master Distiller. His reputation amongst the great distilleries of Dublin was now firmly established, but his ambitions didn’t end there. Brannick had long harboured a burning desire to build the finest distillery in the world, and in 1870, having secured the necessary backing, he resigned his position and struck out on his own, establishing the Dublin Whiskey Distillery Company Limited. DWD.For the next two years Brannick worked on a revolutionary design for his distillery. A site was chosen, less than a mile north of Dublin’s city centre, on the banks of the River Tolka, and construction started on 22 July 1872 Exactly one year later, distillation began with the preparation of the first ever DWD wash. Meanwhile, with work on the great distillery underway, Brannick finally fulfilled another long-standing promise and married his sweetheart Mary Hayes on 26 January 1873.

The young John Brannick soon demonstrated a natural flair for the craft of whiskey-making. These early years, working within the hallowed halls of the John’s Lane Distillery, laid the foundations for his later exploits within the industry. It wasn’t long before the other great distilleries took note of his growing reputation and in 1852 George Roe & Sons enticed Brannick to join the House of George Roe & Co with the promise that he would some day become a Master Distiller.After nearly 20 years of perfecting his craft with the House of Roe, Brannick had reached the illustrious position of Master Distiller. His reputation amongst the great distilleries of Dublin was now firmly established, but his ambitions didn’t end there. Brannick had long harboured a burning desire to build the finest distillery in the world, and in 1870, having secured the necessary backing, he resigned his position and struck out on his own, establishing the Dublin Whiskey Distillery Company Limited. DWD.For the next two years Brannick worked on a revolutionary design for his distillery. A site was chosen, less than a mile north of Dublin’s city centre, on the banks of the River Tolka, and construction started on 22 July 1872 Exactly one year later, distillation began with the preparation of the first ever DWD wash. Meanwhile, with work on the great distillery underway, Brannick finally fulfilled another long-standing promise and married his sweetheart Mary Hayes on 26 January 1873.

Aeneas Coffey Inventor of the Continuous “Patent Coffee Still”

In the year in which John Brannick was born, Aeneas Coffey was granted patent #5974 for his design of a two column continuous still or “Patent Still”. The Patent Still represented a revolution in spirit distillation, eliminating the need for multi-distillation using traditional “Pot Stills” and producing a lighter spirit with a higher proof at a fraction of the cost. However, it was shunned by the great Dublin distilleries, who considered the whiskey produced to be bland and tasteless in comparison with their world-famous “Pot Still” creations. They may have also considered the arrival of the Patent Still a direct challenge to their profession, an early form of automation attempting to replace the distiller’s art and skill. Many years later John Brannick, who went on to become one of the great masters of Pot Still whiskey, would reflect on the irony that the year of his birth marked the establishment of the Patent Still, the nemesis of his life’s work

The DWD Legacy is Reborn

Two old friends meet amid the bustle of the city and retire to the Palace Bar on Fleet Street to remember old times. By chance, one of them notices a bottle – a very old, unopened whiskey bottle with a mysterious, faded label – sitting in a glass case behind the bar. A relic of lost times. ‘What is that?’ he asks the barman. With this simple question, not one but two journeys began: a journey back in time into the extraordinary story of the “Finest Whiskey in the World”, a story of one man’s vision, gloriously realised, crushed by history and destroyed in a very Irish betrayal. And a journey into the future, the future of a once-great distillery, dismantled, neglected and forgotten. Until now. After 75 long years, DWD is back. Today’s DWD is not a copy of the past: a simple reproduction for nostalgia’s sake. Since the distillery closed its doors in 1941 the world has moved on and advances in the art of distilling cannot be ignored. But some values are timeless and remain as cherished and respected as they did when John Brannick laid the cornerstone of his great distillery in theglorious summer of 1872: real character, brave resolve and a true sense of belonging. Today’s DWD is the natural heir of its noble ancestor, a modern whiskey that draws on the wisdom of the past. And this is only the beginning of the DWD revival. In time, Brannick’s great house will be rebuilt, his achievements rivalled and perhaps even surpassed. But for now let us raise a glass to the return of the “Finest Whiskey in the World”, and look forward to the glories yet to come.

The Finest Whiskey in The World

Today, Irish whiskey is regulated and controlled both by international law and the Irish Whiskey Association. The definition of Irish whiskey and the method of production is globally agreed and enforced to ensure industry standards are protected and maintained at all times. However, back in 1880 no such legal definitions existed, and the global success of the industry began to attract the attention of disreputable characters intent on passing off various spirits and concoctions as ‘Irish whiskey’. The problem was made worse by the great distilleries of Dublin, which were content to leave bottling and branding to merchants and bonders. This laissez-faire attitude enabled unscrupulous dealers to import cheap Scotch and pass it off as highly desirable Irish whiskey. True to form, John Brannick was one of the first to recognise the danger and take steps to protect both his whiskey and his customers from counterfeit products. In 1880 he introduced the famous DWD Post Still logo to identify and market the DWD brand. He controlled its use tightly, working only with trusted merchants and bonders to ensure the DWD brand was respected and admired as the “Finest Whiskey in the World”.“The extraordinary story of the ‘Finest Whiskey in the World’, a tale of one man’s vision, gloriously realised, only to be crushed by history and destroyed in a very Irish betrayal.” Tomas – DWD Brand Ambassador

THE GREATEST ACCOLADE

In 1887 Brannick’s achievements and DWD’s greatness were formally recognized by two seminal publications: The Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom by Alfred Barnard and The Industries of Dublin by Spencer Blackett. Barnard’s work has been described as the most important book ever written on whiskey. It was Barnard who first recognised DWD as one of the six “Great Distilleries of Dublin City” by inspecting the distillery in the summer of 1886. Barnard described DWD as “the most modern of the distilleries in Dublin, handsomely designed and of great ornamentation, it rears its head proud and at a distance looks like a monument built to commemorate the virtues of some dead hero.” Barnard also acknowledged “that a mastermind and skilled hand had planned this great work.”The Six Great Distilleries Of Dublin City

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Irish whiskey was the most prestigious whiskey industry in the world. At the heart of this industry stood Dublin, its whiskey recognised the world over as the finest expression of the art and now, with the acclaim of Alfred Barnard and other connoisseurs, DWD assumed its rightful place among the “Great Distilleries of Dublin City”, an exclusive club that brought together the six great masters of Irish whiskey: John Jameson & Co, William Jameson & Co, Sir John Power & Sons, George Roe & Sons, The Phoenix Park Distillery and, of course, the Dublin Whiskey Distillery. -

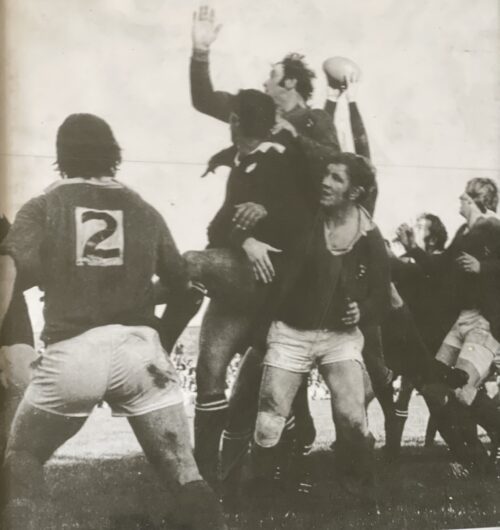

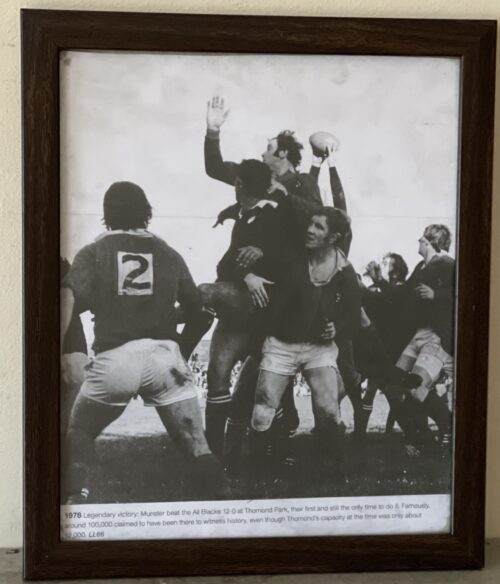

There are many chapters in Munster’s storied rugby journey but pride of place remains the game against the otherwise unbeaten New Zealanders on October 31, 1978. 40cm x 30cm There were some mighty matches between the Kiwis and Munster, most notably at the Mardyke in 1954 when the tourists edged home by 6-3 and again by the same margin at Thomond Park in 1963 while the teams also played a 3-3 draw at Musgrave Park in 1973. During that time, they resisted the best that Ireland, Ulster and Leinster (admittedly with fewer opportunities) could throw at them so this country was still waiting for any team to put one over on the All Blacks when Graham Mourie’s men arrived in Limerick on October 31st, 1978. There is always hope but in truth Munster supporters had little else to encourage them as the fateful day dawned. Whereas the New Zealanders had disposed of Cambridge University, Cardiff, West Wales and London Counties with comparative ease, Munster’s preparations had been confined to a couple of games in London where their level of performance, to put it mildly, was a long way short of what would be required to enjoy even a degree of respectability against the All Blacks. They were hammered by Middlesex County and scraped a draw with London Irish. Ever before those two games, things hadn’t been going according to plan. Tom Kiernan had coached Munster for three seasons in the mid-70s before being appointed Branch President, a role he duly completed at the end of the 1977/78 season. However, when coach Des Barry resigned for personal reasons, Munster turned once again to Kiernan. Being the great Munster man that he was and remains, Tom was happy to oblige although as an extremely shrewd observer of the game, one also suspected that he spotted something special in this group of players that had escaped most peoples’ attention. He refused to be dismayed by what he saw in the games in London, instead regarding them as crucial in the build-up to the All Blacks encounter. He was, in fact, ahead of his time, as he laid his hands on video footage of the All Blacks games, something unheard of back in those days, nor was he averse to the idea of making changes in key positions. A major case in point was the introduction of London Irish loose-head prop Les White of whom little was known in Munster rugby circles but who convinced the coaching team he was the ideal man to fill a troublesome position. Kiernan was also being confronted by many other difficult issues. The team he envisaged taking the field against the tourists was composed of six players (Larry Moloney, Seamus Dennison, Gerry McLoughlin, Pat Whelan, Brendan Foley and Colm Tucker) based in Limerick, four (Greg Barrett, Jimmy Bowen, Moss Finn and Christy Cantillon) in Cork, four more (Donal Canniffe, Tony Ward, Moss Keane and Donal Spring) in Dublin and Les White who, according to Keane, “hailed from somewhere in England, at that time nobody knew where”. Always bearing in mind that the game then was totally amateur and these guys worked for a living, for most people it would have been impossible to bring them all together on a regular basis for six weeks before the match. But the level of respect for Kiernan was so immense that the group would have walked on the proverbial bed of nails for him if he so requested. So they turned up every Wednesday in Fermoy — a kind of halfway house for the guys travelling from three different locations and over appreciable distances. Those sessions helped to forge a wonderful team spirit. After all, guys who had been slogging away at work only a short few hours previously would hardly make that kind of sacrifice unless they meant business. October 31, 1978 dawned wet and windy, prompting hope among the faithful that the conditions would suit Munster who could indulge in their traditional approach sometimes described rather vulgarly as “boot, bite and bollock” and, who knows, with the fanatical Thomond Park crowd cheering them on, anything could happen. Ironically, though, the wind and rain had given way to a clear, blue sky and altogether perfect conditions in good time for the kick-off. Surely, now, that was Munster’s last hope gone — but that didn’t deter more than 12,000 fans from making their way to Thomond Park and somehow finding a spot to view the action. The vantage points included hundreds seated on the 20-foot high boundary wall, others perched on the towering trees immediately outside the ground and some even watched from the windows of houses at the Ballynanty end that have since been demolished. The atmosphere was absolutely electric as the teams took the field, the All Blacks performed the Haka and the Welsh referee Corris Thomas got things under way. The first few skirmishes saw the teams sizing each other up before an incident that was to be recorded in song and story occurred, described here — with just the slightest touch of hyperbole! — by Terry McLean in his book ‘Mourie’s All Blacks’. “In only the fifth minute, Seamus Dennison, him the fellow that bore the number 13 jersey in the centre, was knocked down in a tackle. He came from the Garryowen club which might explain his subsequent actions — to join that club, so it has been said, one must walk barefooted over broken glass, charge naked through searing fires, run the severest gauntlets and, as a final test of manhood, prepare with unfaltering gaze to make a catch of the highest ball ever kicked while aware that at least eight thundering members of your own team are about to knock you down, trample all over you and into the bargain hiss nasty words at you because you forgot to cry out ‘Mark’. Moss Keane recalled the incident: “It was the hardest tackle I have ever seen and lifted the whole team. That was the moment we knew we could win the game.” Kiernan also acknowledged the importance of “The Tackle”.Many years on, Stuart Wilson vividly recalled the Dennison tackles and spoke about them in remarkable detail and with commendable honesty: “The move involved me coming in from the blind side wing and it had been working very well on tour. It was a workable move and it was paying off so we just kept rolling it out. Against Munster, the gap opened up brilliantly as it was supposed to except that there was this little guy called Seamus Dennison sitting there in front of me. “He just basically smacked the living daylights out of me. I dusted myself off and thought, I don’t want to have to do that again. Ten minutes later, we called the same move again thinking we’d change it slightly but, no, it didn’t work and I got hammered again.” The game was 11 minutes old when the most famous try in the history of Munster rugby was scored. Tom Kiernan recalled: “It came from a great piece of anticipation by Bowen who in the first place had to run around his man to get to Ward’s kick ahead. He then beat two men and when finally tackled, managed to keep his balance and deliver the ball to Cantillon who went on to score. All of this was evidence of sharpness on Bowen’s part.” Very soon it would be 9-0. In the first five minutes, a towering garryowen by skipper Canniffe had exposed the vulnerability of the New Zealand rearguard under the high ball. They were to be examined once or twice more but it was from a long range but badly struck penalty attempt by Ward that full-back Brian McKechnie knocked on some 15 yards from his line and close to where Cantillon had touched down a few minutes earlier. You could sense White, Whelan, McLoughlin and co in the front five of the Munster scrum smacking their lips as they settled for the scrum. A quick, straight put-in by Canniffe, a well controlled heel, a smart pass by the scrum-half to Ward and the inevitability of a drop goal. And that’s exactly what happened. The All Blacks enjoyed the majority of forward possession but the harder they tried, the more they fell into the trap set by the wily Kiernan and so brilliantly carried out by every member of the Munster team. The tourists might have edged the line-out contest through Andy Haden and Frank Oliver but scrum-half Mark Donaldson endured a miserable afternoon as the Munster forwards poured through and buried him in the Thomond Park turf. As the minutes passed and the All Blacks became more and more unsure as to what to try next, the Thomond Park hordes chanted “Munster-Munster–Munster” to an ever increasing crescendo until with 12 minutes to go, the noise levels reached deafening proportions. And then ... a deep, probing kick by Ward put Wilson under further pressure. Eventually, he stumbled over the ball as it crossed the line and nervously conceded a five-metre scrum. The Munster heel was disrupted but the ruck was won, Tucker gained possession and slipped a lovely little pass to Ward whose gifted feet and speed of thought enabled him in a twinkle to drop a goal although surrounded by a swarm of black jerseys. So the game entered its final 10 minutes with the All Blacks needing three scores to win and, of course, that was never going to happen. Munster knew this, so, too, did the All Blacks. Stu Wilson admitted as much as he explained his part in Wardy’s second drop goal: “Tony Ward banged it down, it bounced a little bit, jigged here, jigged there, and I stumbled, fell over, and all of a sudden the heat was on me. They were good chasers. A kick is a kick — but if you have lots of good chasers on it, they make bad kicks look good. I looked up and realised — I’m not going to run out of here so I just dotted it down. I wasn’t going to run that ball back out at them because five of those mad guys were coming down the track at me and I’m thinking, I’m being hit by these guys all day and I’m looking after my body, thank you. Of course it was a five-yard scrum and Ward banged over another drop goal. That was it, there was the game”. The final whistle duly sounded with Munster 12 points ahead but the heroes of the hour still had to get off the field and reach the safety of the dressing room. Bodies were embraced, faces were kissed, backs were pummelled, you name it, the gauntlet had to be walked. Even the All Blacks seemed impressed with the sense of joy being released all about them. Andy Haden recalled “the sea of red supporters all over the pitch after the game, you could hardly get off for the wave of celebration that was going on. The whole of Thomond Park glowed in the warmth that someone had put one over on the Blacks.” Controversially, the All Blacks coach, Jack Gleeson (usually a man capable of accepting the good with the bad and who passed away of cancer within 12 months of the tour), in an unguarded (although possibly misunderstood) moment on the following day, let slip his innermost thoughts on the game. “We were up against a team of kamikaze tacklers,” he lamented. “We set out on this tour to play 15-man rugby but if teams were to adopt the Munster approach and do all they could to stop the All Blacks from playing an attacking game, then the tour and the game would suffer.” It was interpreted by the majority of observers as a rare piece of sour grapes from a group who had accepted the defeat in good spirit and it certainly did nothing to diminish Munster respect for the All Blacks and their proud rugby tradition.He said: “Tackling is as integral a part of rugby as is a majestic centre three-quarter break. There were two noteworthy tackles during the match by Seamus Dennison. He was injured in the first and I thought he might have to come off. But he repeated the tackle some minutes later.”“Jack’s comment was made in the context of the game and meant as a compliment,” Haden maintained. “Indeed, it was probably a little suggestion to his own side that perhaps we should imitate their efforts and emulate them in that department.” Tom Kiernan went along with this line of thought: “I thought he was actually paying a compliment to the Munster spirit. Kamikaze pilots were very brave men. That’s what I took out of that. I didn’t think it was a criticism of Munster.” And Stuart Wilson? “It was meant purely as a compliment. We had been travelling through the UK and winning all our games. We were playing a nice, open style. But we had never met a team that could get up in our faces and tackle us off the field. Every time you got the ball, you didn’t get one player tackling you, you got four. Kamikaze means people are willing to die for the cause and that was the way with every Munster man that day. Their strengths were that they were playing for Munster, that they had a home Thomond Park crowd and they took strength from the fact they were playing one of the best teams in the world.” You could rely on Terry McLean (famed New Zealand journalist) to be fair and sporting in his reaction to the Thomond Park defeat. Unlike Kiernan and Haden, he scorned Jack Gleeson’s “kamikaze” comment, stating that “it was a stern, severe criticism which wanted in fairness on two grounds. It did not sufficiently praise the spirit of Munster or the presence within the one team of 15 men who each emerged from the match much larger than life-size. Secondly, it was disingenuous or, more accurately, naive.” “Gleeson thought it sinful that Ward had not once passed the ball. It was worse, he said, that Munster had made aggressive defence the only arm of their attack. Now, what on earth, it could be asked, was Kiernan to do with his team? He held a fine hand with top trumps in Spring, Cantillon, Foley and Whelan in the forwards and Canniffe, Ward, Dennison, Bowen and Moloney in the backs. Tommy Kiernan wasn’t born yesterday. He played to the strength of his team and upon the suspected weaknesses of the All Blacks.” You could hardly be fairer than that – even if Graham Mourie himself in his 1983 autobiography wasn’t far behind when observing: “Munster were just too good. From the first time Stu Wilson was crashed to the ground as he entered the back line to the last time Mark Donaldson was thrown backwards as he ducked around the side of a maul. They were too good.” One of the nicest tributes of all came from a famous New Zealand photographer, Peter Bush. He covered numerous All Black tours, was close friends with most of their players and a canny one when it came to finding the ideal position from which to snap his pictures. He was the guy perched precariously on the pillars at the entrance to the pitch as the celebrations went on and which he described 20 years later in his book ‘Who Said It’s Only a Game?’And Tom Kiernan and Andy Haden, rugby standard bearers of which their respective countries were justifiably proud, saw things in a similar light.“With that, he flung his arms around me and dragged me with him into the shower. I finally managed to disentangle myself and killed the tape. I didn’t mind really because it had been a wonderful day.” Dimensions :47cm x 57cm“I climbed up on a gate at the end of the game to get this photo and in the middle of it all is Moss Keane, one of the great characters of Irish rugby, with an expression of absolute elation. The All Blacks lost 12-0 to a side that played with as much passion as I have ever seen on a rugby field. The great New Zealand prop Gary Knight said to me later: ‘We could have played them for a fortnight and we still wouldn’t have won’. I was doing a little radio piece after the game and got hold of Moss Keane and said ‘Moss, I wonder if ...’ and he said, ‘ho, ho, we beat you bastards’.