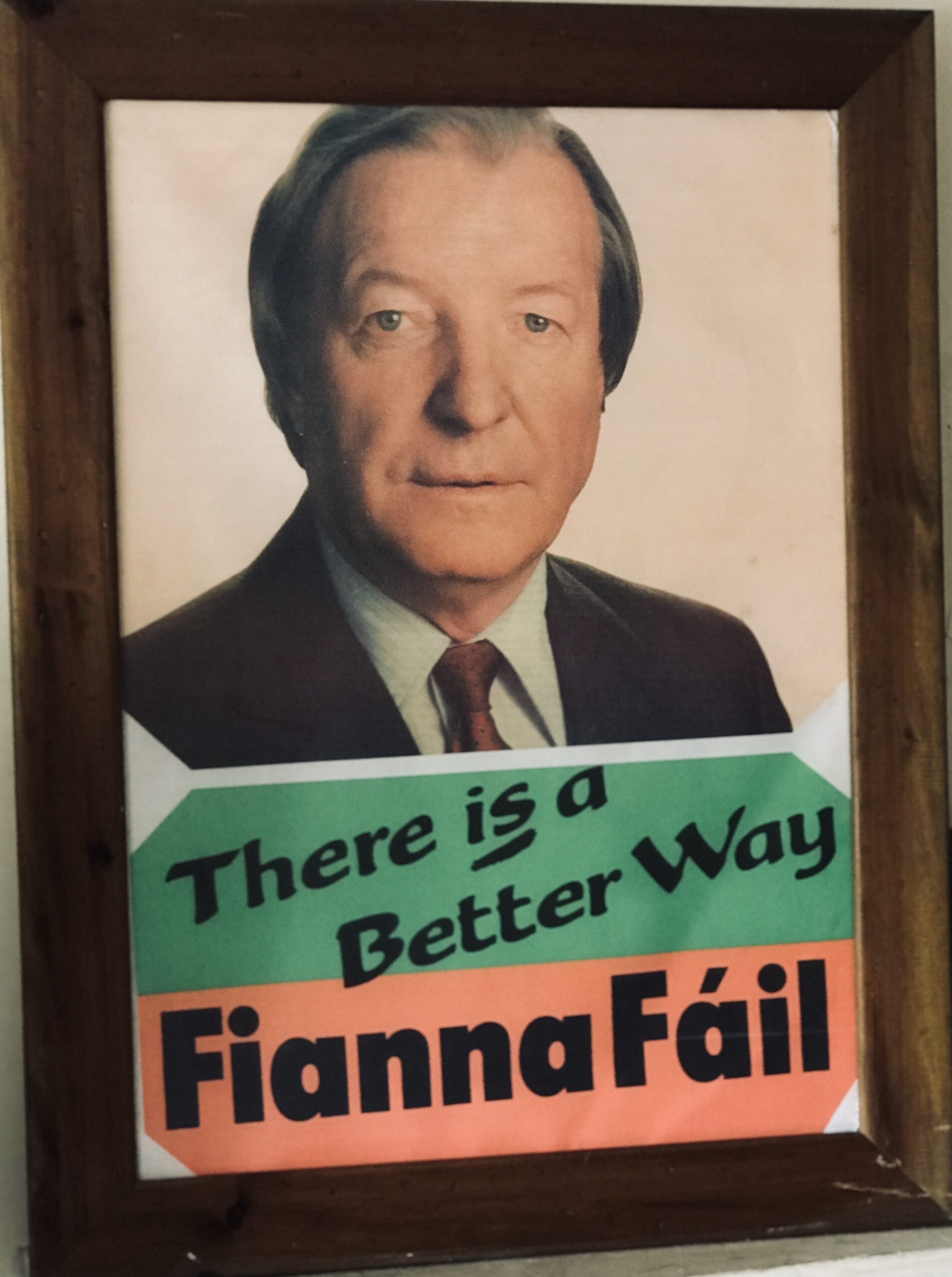

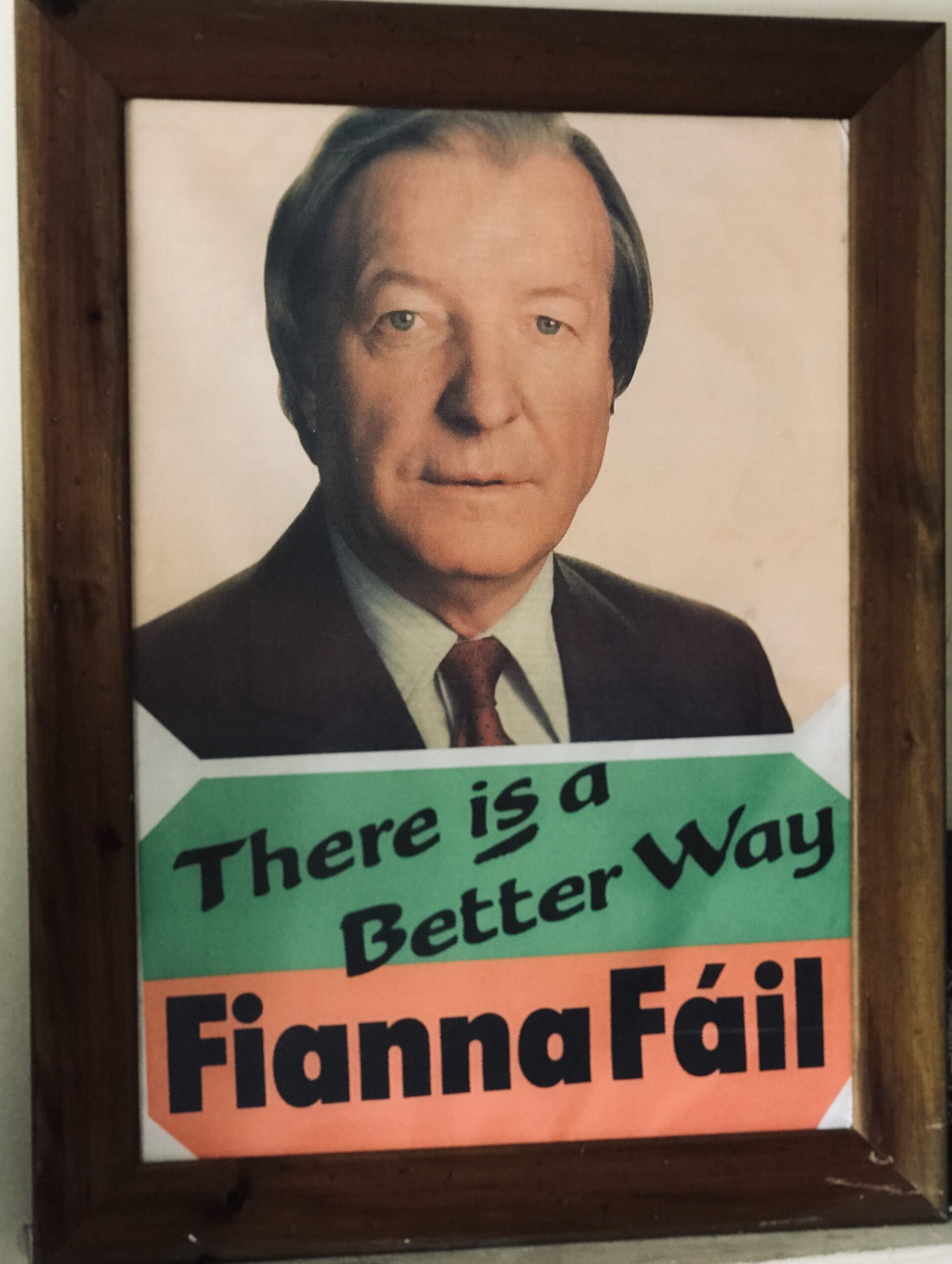

Original Fianna Fail Charles J Haughey Election Poster from the 1980s.Anyone who remembers the period of Irish Life when Charlie held sway over the country will either look at this poster with fond admiration or in horror -there is no middle ground !The most polarising and controversial figure of modern Irish history.

Dublin 83cm x 63cm

When, after protracted negotiations, numerous disappointments and postponements, you finally get to interview Charles J. Haughey, it emerges that the procedure is slightly differenet than with other interviews. First of all Charles J. Haughey interviews you. This, presumably, is so that he can reassure himself that you’re not the kind of person who’s going to come out with what is eloquently summed up by his colourful press secretary P.J. Mara as “any of that Arms Trial shite.”

P.J. is very good on the subject of what happens when people do. Or when they confront The Boss with Sean Doherty, telephone tapping and tape-recorders. “The shutters come down,” says P.J., illustrating graphically with both hands the downward motion of imaginary shutters descending to obscure Charles J. Haughey’s face. “The fuse starts to burn. And then you’ve had it.”

*****

“You like very MI5-ish,” says C.J. Haughey as he rises to greet the Hot Pressreporter. His right hand is pressed against the left side of his midriff; either he’s trying to look Napoleonic or the stomach is at him. “What in the name of Jazus do you want to talk to me about?” Haughey’s tone is one of wearied resignation, leavened with a sizable dollop of friendliness. P.J. Mara points out that all the details were in the letter he gave him a few weeks ago.

“What letter?” Haughey demand blankly. “You gave me no letter. You never give me anything!” His gaze, mischievous but unflinching, meets P.J.’s head on. He knows that P.J. knows that he knows that in all probability P.J. did give him the letter. P.J. keeps his counsel.

It’s explained to Haughey that rather than dealing with the nitty gritty of issues and policies – his views on which are already well documented – the interview will be personal in emphasis. We would like to talk to him about issues affecting young people in modern Ireland but with particular reference to his own experiences as an, ahem, young person.

A flicker of a smile breaks through Haughey’s blank, quizzical expression. “Sure I’d never be able to remember that far back! That’s a long time ago.”

What kind of “issues”?

Crime, vandalism…

“Well what could I say about that?” he thinks out loud. “I don’t think I could say that I approve of youngsters knocking off BMW’s and so on,” he muses. “Although, I must admit, I always had a hidden desire to do something like that! I don’t suppose I could say anything like that, now could I?”

Hardly.

“What kind of other issues?”

The drug problem…

“Sex?” he asks and smiles sardonically. The reporter takes the opportunity to stress that the whole point of the interview is to portray the lighter, more personal side of Charles Haughey, which doesn’t normally come across in the media. Most people see him as an austere individual.

“Oh but I am austere” he responds, deadpan. “Deep down I’m very austere.” There isn’t the merest flicker of a smile. The reporter meets his stare, wondering if he’s supposed to laugh. He does. So does Charles J. Haughey. The reporter, it appears, has passed the audition, and the interview is duly arranged for the following Monday, which as it happens is the day that Garret Fitzgerald and Margaret Thatcher are due to have their now infamous summit meeting.

“What other people have you interviewed?” Haughey enquires.

The reporter does a quick mental check, in search of some respectable names to drop. For some odd reason he mentions Christy Moore. “Ah, he’s a bit of a rebel, isn’t he?” remarks Charles J. Haughey. “Christy wants to change the world!” He pauses. “I gave up trying to change the world a long time ago.”

You were born in Castlebar. How much do you remember about it?

“Well, I was only born in Castlebar. I left at a stage I don’t even remember. As a child I lived in Dublin, to all intents and purposes. I also spent a lot of summer holidays in the north, in my grandmother’s house. It was a small farm and I got a very good insight there of life on a small farm and of the social life and economics of small farming. And I also got a very clear impression of the community situation in Northern Ireland – how the Catholic small farmers viewed their Protestant neighbours and how they lived with them. But all my life, really, was spent in Dublin. I mean, I’m a Dublin person.

Were you very bright at school?

“I’m afraid I was, yes. In those days there used to be a Dublin Corporation scholarship at primary school level, and I got first in Dublin.

You went to the Christian Brothers. They had quite a reputation in those days for violence towards pupils…

“I would reject that. I liked school. By and large, the games at school made up for the less attractive side of it. If you did something particularly awful or outrageous, you got the leather, but it certainly left no lasting scars on me. It was just something of momentary importance. Tomorrow was a new day and the school would be playing Brunner – which was Brunswick Street – in the Phoenix Park, and you’d be off to that.

What other kind of pastimes did you have?

“Well the main preoccupation in life was football and hurling – playing for the school and later for Vincent’s and Parnell’s. At a younger stage in my life I used to take up things like birdnesting – collecting bird’s eggs maybe. What else did we do? We went to the pictures once a week – if we had the money. KIds those days didn’t have any money.”

What kind of films did you like?

“Well now…(pause)They’re all jumbled up in my mind. Cowboy films were the big deal. People like Gene Autrey and things like that. Then, later on, I suppose, Humphrey Bogart and things like that. War films.

Do you go to the cinema nowadays?

“No. (Shakes head) very rarely.”

Can you remember the last film you went to?

“No (laughs) I don’t know.”

What was it like to be a teenager in your day?

“When I was a teenager, the war was on, so the whole environment was totally different. Of course there were no motor cars. Everybody went on bikes. The whole country was down to subsistence level. You couldn’t leave the country – there was no foreign travel. Young people today know absolutely nothing about it. (Pause) But it wasn’t all that terrible. Looking back on it now you’d think it must’ve been awful, but it wasn’t really.”

There wouldn’t have been a lot of teenage crime in those days…

“No. Almost certainly not. Literally, we only saw a policeman when he came to stop us playing football on the road! Of course we robbed orchards and things like that, but there was no great tension about it.”

Do you think the advantages outweighed the disadvantages, that it was a better time to be growing up than today?

“Ah, no. (Pauses) I wouldn’t say it had any advantages, to be honest with you. I think teenagers today have a great time. I don’t mean just now, in the middle of this terrible economic recession, but for a long period post-war, most of them had a great time – great opportunities, all sorts of new things: television, the exploration of space and all these things. And they had a thing that we never could have as teenagers, foreign travel. We just couldn’t leave the country – unless you wanted to go off and join the British army, and fight in the war!”

What are your recollections of the war?

“The big thing was the number of one’s friends that went off to join the British army. Because there was no work. You either joined the Irish army or the British army. And kids, if they were in a rebellious mood, and were, y’know rowing with their teachers or parents, they’d go “Fuck you! I’ll go off and join the British army if you don’t appreciate me or treat me properly!”

Did you ever try that one?

“No, I never said that. I was in the L.D.F. and the F.C.A. subsequently.”

As a young man, did you have any inkling that one day you might end up as Taoiseach?

“No. Not in the slightest.”

You weren’t aware of being different or special in any way?

“Oh Jesus Christ, no!! (Laughs)”

What difference do you notice between young people nowadays and back then?

“Well, the big difference is that young people today have far more confidence. Admittedly they’re probably very depressed immediately now, about job prospects and so on. But apart from that, they have far more self-reliance and confidence than we ever had. They’re a more sure generation. Our outlook, our scope, our dimensions were very limited. When I was young, you were very restricted in terms of careers. You dedicated yourself to the Civil Service or teaching, or whatever. It was all very regimented. It was very important to have what was known as a “good job”. But young people today have none of those inhibitions. They couldn’t give a damn about anything like that. And also, the way they dress: in our day it was very important to wear the right kind of clothes – you had to have a suit and tie and so on; nowadays kids are quite happy to go around in a pair of jeans and a jumper.

“I think young people today are fabulous. I love to be with young people. They make me feel good. I love their attitude to life. ”

What advice would you give to young people who feel depressed by the current economic climate?

“Well the first thing I’d say to them is “stay here”. I don’t think it’s any better anywhere else. I know a lot of my son Ciaran’s friends are now in New York. There’s a lot of young Irish people now opting for that sort of sub-stratum in New York or maybe London – they’re working as barmen and waiters and waitresses and that sort of thing. But what I would say to young people is: “Stay, if you possibly can.” I think that this present situation is a temporary aberration, a loss of direction, a loss of will and a loss of political leadership, and that there is, and that there is, there must be, a future here. I know that a lot of them are fed up doing courses training for jobs that aren’t there. (Pause) On the other hand, we’re moving into a technological world – computers and electronics and so on. It’s a world that’s very foreign to me. I don’t understand it. Like my kids now – they treat me like a semi-imbecile, because I don’t know how to work tape-recorders and videos, and record things! And, y’know, when I’m going out and there’s a programme on television that I want to record on the video, I have to get one of them to do it. They say: “Ah, go away! Leave it to me. I’ll do it for you!”

“So that, it’s their world. And I think we’re very, very fortunately placed in Ireland in that whole area. We’ve a small population and it’s an intelligent population. It’s well-educated. And, as I said, I think they’re terribly confident and self-assured in a way that we weren’t in our day. And they have a far better grasp on the world and don’t mind getting in an aeroplane and going to Germany or the United States. When you think about it, our total workforce is a million – which is nothing, if you take it that the normal running of the country takes the vast bulk of them. So you’re really only dealing with a couple of hundred thousand people, and that’s not a lot to train and educate for these new technological industries.”

Have you studied the report of the National Youth Policy Committee?

“Ah, no. I know exactly what I want for young people and I don’t need any committee to tell me. I know, from my own constituency, what’s needed: they need plenty of facilities – sporting facilities, particularly. I’m a bit old fashioned: I really believe that kids who are into sport – football, hurling, racing, any good sporting activity – never get into drugs or anything else. It’s a simple thing I’ve always found. Didn’t have time! So I believe in giving them everything possible for sports and recreational activities. That’s the first thing. And then jobs: give them the training for the very best scientific and technical jobs. It’s been proved that, far from being intimidated by this technical stuff, it’s a cake-walk for them. Kids have taken to playing with computers now. I’d be afraid of them! I just couldn’t do it. And that’s a tremendous thing: what should be a great, big intimidating, fearsome new world, is in fact child’s play to them. So I’d get them a hundred million pre cent into all that technological and science-related area.”

“After that, I’d love to see every single young person having some creative side to their life. I think a whole new dimension has to be grafted onto our educational system, to try and get every youngster into doing something in a creative sense.”

Do you subscribe to the current viewpoint which sees our large young population as some kind of “problem”?

“I don’t know. I don’t think so, basically. It’s hard to say. There are a lot of young people around now. Y’know? You go through towns and streets – like where I live in Malahide – and it’s crawling with young people. Drive through the country – there’s young people everywhere. And therefore, to that extent, our society is presumably more volatile than an older, more conservative, settled type of society. Ant that’s bringing changes, there’s no doubt about that. But I don’t think that there’s any…I wouldn’t be all that worried about an explosion. Y’see, if you go back, all the campuses in America were exploding and you had the French situation – well that’s all suddenly changed. There’s a big reversal, I think now, among young people. They’ve become much more cautious – not conservative. But much more committed to trying to find their own way in life, rather than trying to change society. Somebody told me they were in U.C.D. recently, and they were astonished at how conservative the place had become – not conservative really, but how settled down it has become, how serious everybody is.”

Yes. The ’80s seems to be a complete revesal of the ’60s?

“Oh, a total reversal. I think that’s true, isn’t it?”

You’d have been in your mid-thirties at the beginning of the ’60s. Were you aware of the Beatles and all that stuff?

“Oh very much. Well. Y’see, I experienced all through my children. I saw what they were doing and what they were interested in. So I was very aware of it. Not part of it, but very conscious of what was happening and what was affecting young people and what their interests were. And I could see the amazing changes in them, between them and me as a young fellow.”

Did you go to dances as a teenager?

“Oh yes. The local dances in the local halls. Much the same as they are now. There wasn’t such a thing as a disco as far as I know. Just a band, y’know? Dance bands.”

What kinds of music?

“American music, largely. American jazz and American music. One of the big things that came in my lifetime was the swingback to traditional music and folk songs, the Dubliners and all that. When I was young, that sort of thing wasn’t happening. The Clancy Brothers started all of that, I think.”

What do you think of the current adulation of pop stars?

“I think it’s perfectly understandable. Kids always related to someone. We idolised somebody – I don’t even remember who it was – some female filmstar. I can’t even remember their names now! (Laughs) But we sort of related to them and idolised them and worshipped them. A big deal! And it’s not any different now. No. I understand that completely.”

It is, perhaps, slightly different insofar as the modern day stars like Boy George and so on wear make up and dresses and are openly bisexual.

“Yeah, but there’s also a tremendous following for people like the Dubliners. Ronnie Drew. And my friends The Fureys – they have their own following, and…Ah no, there’s a sort of a healthy disparateness about the whole thing. I mean what was the last fellow in Croke Park there now? Or Slane Castle? Y’know? I totally appreciate and understand that. My kids go to that.”

What do you think of Boy George?

“I don’t know anything about him. He seems a bit weird. But most of them, I think are top class musicians and professional artists.”

You like the Fureys a lot?

“I love the Fureys. I think they’re great. My favourite piece of music is “The Lonesome Boatman” as you know. But I also think the Chieftains are fabulous. I’d go anywhere to hear the Chieftains and the Dubliners, and most of those.”

What about the Wolfe Tones?

“Yeah. I like them. They’re a bit of the ould rabble-rousin’, but sure they’re alright! (Laughs) They’ve a very sort of limited medium, haven’t they?

What about country and western? Do you like that at all?

“No (Shakes head) I don’t. I never hear it. (Laughs) I don’t know if I should say that, because Paschal Mooney is on the National Executive of Fianna Fail!”

Do you think that there should be some mechanism to allow young people a quicker access to politics?

“Politics is not the Boy Scouts! It’s a bit of a haul. And I think, per se it has to be; you’ve to sort of win your spurs and fight your way through. It’s like anything: it’s like what we were talking about – music and the entertainment world. It’s a long, hard haul: most of the guys who are at the top have served out a pretty tough, demanding apprenticeship. And politics is the same. Experience counts a lot in politics. I don’t mean that we all have to be like the Chinese: eighty years of age and very wise. But you have to find your way and get to know and handle people.”

Young people are very cynical about politics and politicians.

“But sure, everybody hates politicians! (Laughs) Old people are not any different. The ordinary guy in the pub thinks politicians are all useless and crooked and so on. That’s not confined to young people. That’s a healthy cynicism and distrust which most modern democracies – and certainly the Irish people – have always had, at all ages.”

Do you think that the Irish are a particularly political race?

“They’re tremendous politicians, the Irish people. They’re fascinated with politics. The ordinary guy in the pub can talk more intelligently and more wisely and with more depth about politics than anybody in any country in the world. Certainly he’s about fifty times ahead of his bovine English counterpart, who knows about Margaret Thatcher and maybe one or two others – but that’s all he knows.”

“You see, the Irish invented American politics. The whole American system is Irish founded and based. They made the Democratic Party. Brian Lenihan is very good on this – he’s made a study of it. The Irish were trained here in local politics back in the 19th Century, and when they went to the States they knew how to handle things, which most of their European counterparts didn’t. The German and the French, for instance, knew nothing about democratic politics – they came from empire states. ”

One of the tendencies we’ve imported from America is the increasing emphasis on the personalities.

“Yes. It’s become increasingly so now, with the media. The individual politician or political leader becomes the focus, because the media haven’t the interest or don’t care about the issues. They’re too tedious and take too much time to explain. They’re much more interested in trying to hone in on A, B or C – on one person and what they’re thinking and doing.”

You see that as a negative development?

“It’s a bad thing, yeah.”

But we Irish do seem to go for a strong personality.

“Well, it’s very tribal you see. In rural Ireland, particularly, you have rural Chieftains, like Blaney in Donegal and so on. I suppose it’s a throwback to, a descendent from the Irish Clan/Chieftain system.”

Yet politicians generally come across as fairly straight-laced, humourless, one-dimensional people.

“I think politicians are hard-done-by, but then everybody thinks that about their own profession, I suppose. I don’t think that the criticisms of politicians are very well balanced. Nobody ever sets out to try and describe a politician in the round, and say okay, maybe he’s very wrong about this, but at least he’s trying to do that. But then there’s no point in complaining about that. That’s part of the apparatus of political life – to be attacked and criticised. Very often, in one’s own view, almost continually wrongly.”

“And there’s another thing about this, which is that the ordinary…I hate using that word but it’s hard to find another. There’s no such thing as ‘ordinary people’: there’s just people but, people are not fooled by all of this. I know that I have a perfectly good relationship with my people, my constituency. They know me, I know they trust me and I think they like me. They don’t think I’m a bad person or am out to do anything detrimental to them or to their interests. And that’s what matters. That is the compensation for when you read something in the paper that you know is unfair – grossly unfair – and wrong. And when that happens you’re inclined to get outraged and angry about it, and upset about it. But that’s only passing.”

“But, if the day ever comes when I’m driving through the city and the busman doesn’t say “Howya Charlie?” or the taxi fellow doesn’t say “Hello there, how’s the goin’?” – if that day comes, then I’ll be upset. All this stuff in the newspapers – it does upset, I can’t deny that. You’d be a particularly insensitive and inhuman sort of individual if it didn’t bother you, from time to time. But it’s passing. The other thing is the reality. That’s the sustaining reality.”

What aspect of Ireland or Irish society angers you the most?

“Ah, there’s nothing really. I couldn’t live anywhere but in Ireland. I’m not perpetually angry about anything. I might suffer minor irritations, exasperations or anger about particular things, but…no, I like living in Ireland and in the Irish community. (Here, he pauses at length and reflects, he looks me straight in the eye before continuing). I could instance a load of fuckers whose throats I’d cut and push over the nearest cliffs, but there’s no percentage in that! (Laughs)

“Smug people. I hate smug people. People who think they know it all. I know from my own experiences that nobody knows it all. Some of these commentators who purport to a smug knowallness, who pontificate…They’ll say something today and they’re totally wrong about it – completely wrong – and they’re shown to be wrong about it. Then the next day they’re back, pontificating the same as ever. That sort of smug, knowall commentator – I suppose if anything annoys me, that annoys me. But I don’t have sleepless nights about it.”

Were drugs a big concern for you when you’re kids were growing up?

“I have to say it was more of a worry for me as a politician than as a parent. I was lucky in that I’ve never, never….well, I don’t know what temptations my kids had to confront or to deal with, but they did whatever they were. And indeed none of their pals, that I know of, ever dropped out or became addicted or anything like that. It was just, I suppose, one of those chances of life, that they happened to be in a milieu of their own crowd, who didn’t get involved in all that.”

On the subject of the current contraception debate: isn’t it true that the actual behaviour and practice of young people has long since made the question irrelevant?

“(Pause) Ah yeah, I think that’s probably true enough.”

It’s all very academic at this stage…

“Yeah. (Laughs) I think so, yeah.”

What about in your own day? Was it like that then?

“Ah now! (Laughs) To my dying day, I’ll regret that I was too late for the free society! We missed out on that! It came too late for my generation!”

“But yes, there was a very definite change. See, when I was young, too, authority was much more of a thing. Authority in society, in the community, in school, and of course the guards. You were afraid of the guards. Nowadays, kid’s aren’t: they just call them “pigs”, y’know? But in my day, if a guard said to you “fuck off”, you fucked off as quick as you could! There was far more authority, and that was a big change. Kids nowadays have developed their own ethos and mores. And I think we’ve changed as parents too. I think we were much more understanding and sympathetic to our children than our parents were to us. My mother knew what was best for me, and told me what to do, and what not to do, and insisted that I did or didn’t do it. I wasn’t like that with my children. We certainly trusted them far more. We felt that what you had to was just give them a home where they knew they were important, where they were loved and where they were trusted and where they could always come back to. If they made a fuck-up of things, they could always come back home and they would be welcomed and looked after and protected and helped. But our parents were different. So, not alone are young people different today, but we as parents were different to them.”

So is there a dichotomy there between how you would find yourself responding to issues, like contraception, as a parent, and the way you would feel obliged to respond to them as a politician?

“Well…..no.(Long pause) You could exaggerate that. Y’see politics is concerned with more than just sexual morality and contraceptives and things like that. Now, mind you, these are the things that have a moreorless fatal preoccupation for journalists. It’s extraordinary that for one journalist who comes to me and asks me my views on economics, or the health services, or social welfare, or the North of Ireland, there’s ten that want to know what I think about contraceptives. We, in the political world are dealing with practical things. The social welfare system, for instance, looms very large in modern society – all the anomalies and the problems and the snarl-ups – that’s an enormous area, and it affects far more people than the contraceptives thing.”

What about the Nuclear issue – how do feel about that – on a personal level?

“I’m increasingly angry about it, I think it’s just lunacy itself – the stockpiling of atomic weapons. Like, what’s going to happen? What are they there for? Ah, I don’t, I suppose, basically believe that we’re all going to be wiped out tomorrow morning by a nuclear war. I suppose if any of us really believed that we’d just go and stick our heads in a gas oven. It’s too awful to contemplate. Even the most grotesque film can only give you the vaguest impression of what the devastation is likely to be. So I don’t suppose, basically that I really think that we’re going to go up in a nuclear holocaust. But I do think that it’s a very real danger.”

Is there anything that can be done about it?

“Sometimes I like to think that you could get all the nuclear arms into one, great big rocket – remember that rocket that went away into outer space once? It was going to go around Mars once and then go away into the infinite, never to be seen again. Well, if you could put all the nuclear weapons into some sort of rocket like that. (Pauses, laughing) But, sure, when the rocket would blast off, you’d probably go up anyway! But it’d be a marvelous solution.”

Maybe it’d be safer if we all took off in the rocket and left the bombs here…

“(Laughs) Yeah! You take your pick and I’ll take mine! But what’s going to happen? I don’t know. (Pause) The question of nuclear waste too, and the pollution of the seas and the atmosphere is something that worries me. Not paranoiac, or dramatically, or emotionally disturbed about it, but I can understand people who are. I get increasingly angry at the failure of mankind to get to grips with it.”

What do you do in your spare time?

“Anything that comes up of interest, I’ll have a go at it. Most recently, I like to go down to my island, Inishvickillane. The main attraction of the island, apart from its natural beauty, and the wildness of it, is that we’re more of a family down there. Fortunately, the kids and the wife like it as much as I do. It’s as much their place as mine. I really got to know my kids better down there: in Dublin we’re always coming and going. We meet tangently, coming and going out in the hall. But down there we’re together, and we share experiences together. But I try and do as many things as possible. Like, for instance, my son Conor is an expert on scuba-diving, and I’ve got him to give me a little bit of instruction on that.”

Do you read much?

“I do and I don’t. I certainly don’t read anything like as much as I should. When I was younger, and at school and that, I read and read and read and read. I just read everything. But it’s so difficult: you read a review of a book and you say “I must read that”. And then there’s another one. There’s so much going on in the world of literature that even if you had the time, it’s very difficult to decide what to read. There’s so much you want to read.”

What would you read, if you had the time?

“Well, let me see now…I like history type of books – historical novels, that sort of thing. And then I’m increasingly interested in wildlife, in nature, in the sea, and all that type of thing.”

Do you watch much television?

“No. Not very much. I think most television is tripe. Boring rubbish. To me, television is the News, or occasionally some very good documentary-type programmes. Very few. The News, some documentaries and sport.”

Do you ever see Dallas or any of those things?

“(Laughs) I see them because I have to confess that in my home there are those who look at Dallas. And well, I might go and do a bit of work, but sometimes I might sit through it. I really think it’s shit. I think it’s terrible shit. But then I know that’s a minority view. (Laughs) I think most people think it’s shit, like, but they look at it all the same.”

Did you have any heroes growing up?

“Well, I suppose Sean Lemass. He was the greatest human being that I ever met. Or could ever hope to meet.”

What is the most important quality in a friend?

“Wel, there was a great word, d’ya see, that Sean Lemass in his whole life instanced but could never pronounce. Like most Dublin people, he could never pronounce “loyalty” – he always pronounced it “loylaty”. And I think that’s the most important thing: loyalty. A Dublin man’s loylaty. Not loyalty, because that’s something different. But loylaty. I think that’s the most important characteristic in friends.”

Christmas is only a few weeks away now. Do you like Christmas?

“Oh yeah! And I have to be at home for Christmas. To me, Christmas is a Dublin thing. I couldn’t be anywhere else except home in Dublin for Christmas, meeting all my friends, having a drink with them, giving out presents, getting presents. I’m a sucker for Christmas!”

Is there a day in your life that you remember as the happiest?

“Oh, FUCK OFF!! (Laughs) No!!! You’re turning into a fuckin’ woman’s diary columnist now!’

Have you ever read George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four?

“Yes.”

What would find in Room 101? What, for Charles J. Haughey, is The Worst Thing in the World?

“Ah, I’m not too introverted like that. (Pause) Deep down, I’m a very shallow person. (Laughs)