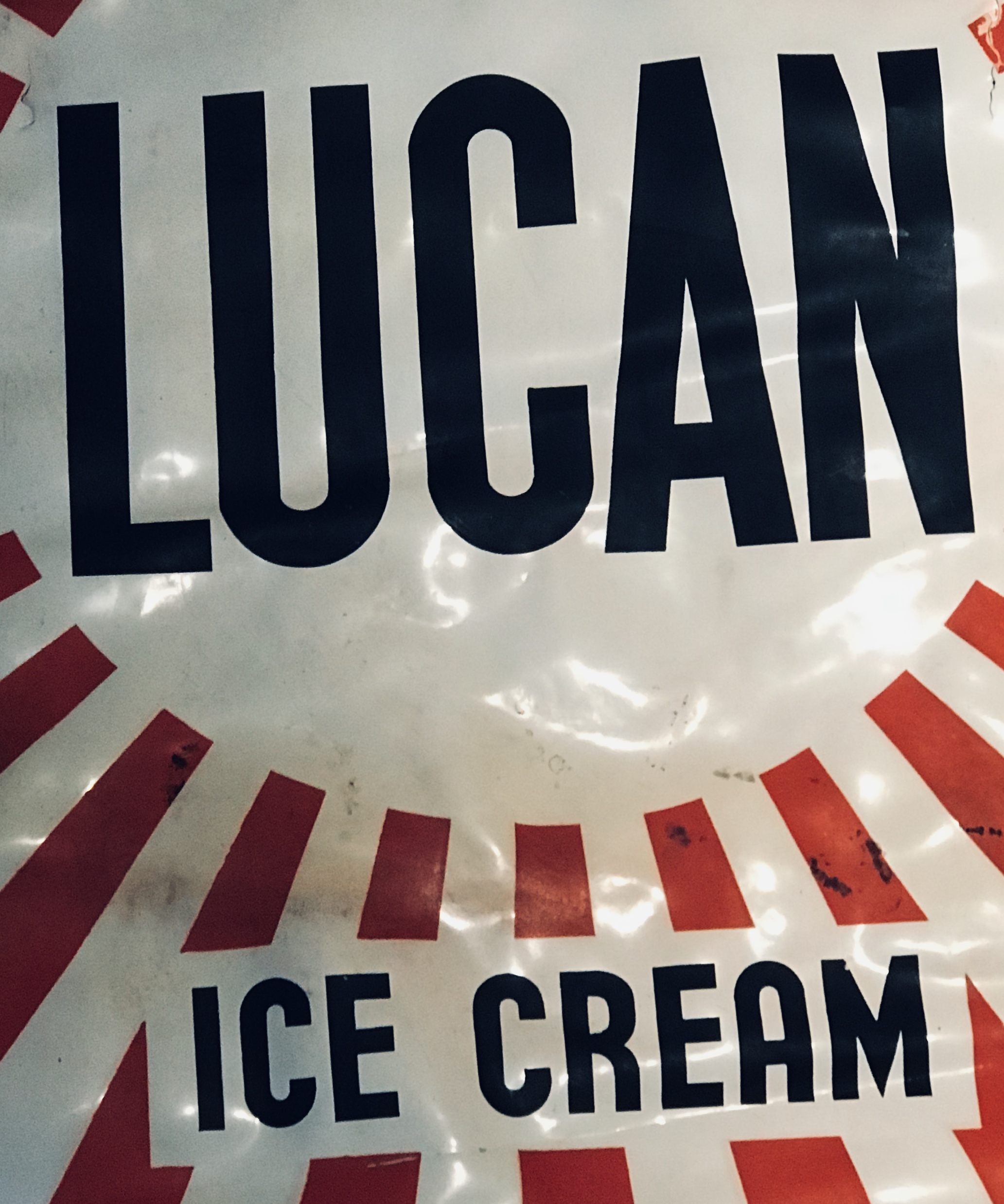

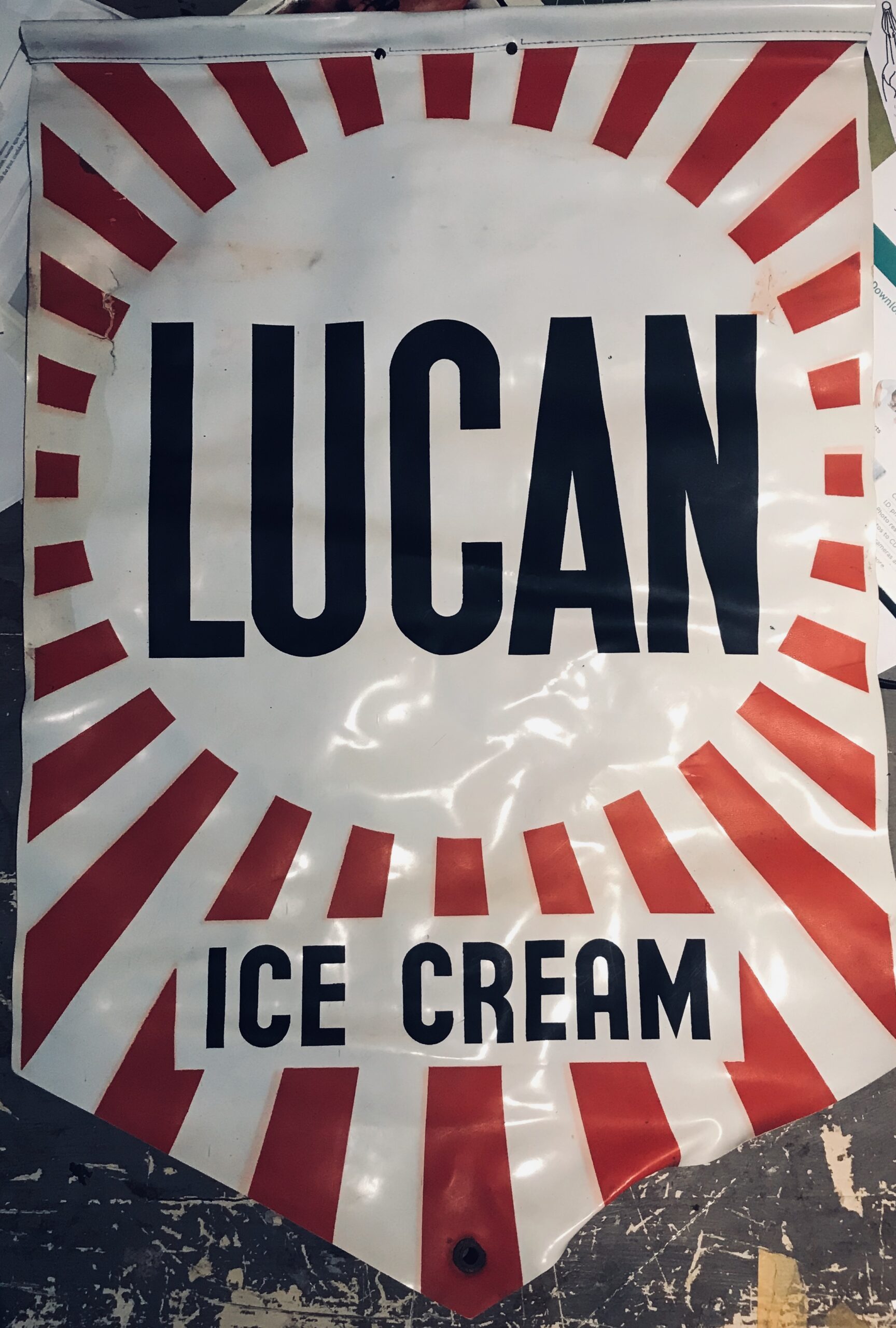

Extremely rare 1950s Lucan Ice Cream Double sided Vinyl Advertising Banner .

Castlegregory Co Kerry 65cm x 46cm

(From the Irish Times 2003 )As our best-known ice- cream factory prepares to close, Kieran Fagan tells its story – and that of one of its staff, who provided a celebrated comedy moment of the 1950s

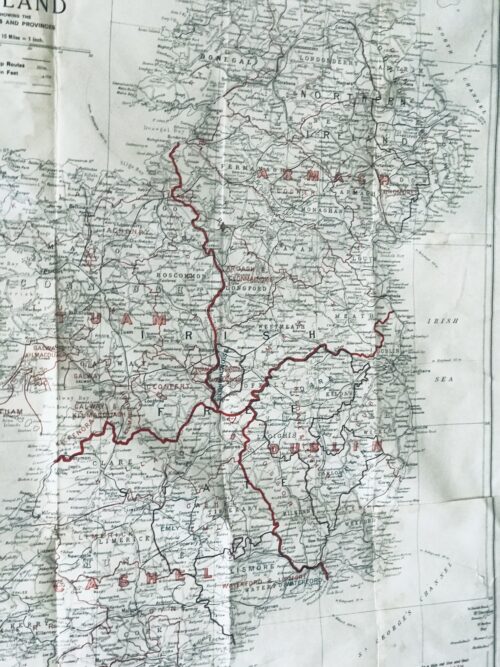

Horses once grazed in the field where the HB ice-cream factory stands, opposite Nutgrove Shopping Centre, in Dublin. But these were working horses. For a living they pulled milk drays, leaving Hughes Brothers dairy early in the morning, knowing where to stop on their routes in south Co Dublin. The roundsmen raced from house to house, arms laden with milk bottles, while the horses ambled steadily forwards. When they were replaced by electric vans, deliveries slowed down, as the vans could not keep up as the horses had done. Nor did they know which houses to stop at.

When Paul Mulhern started work at HB, as a holiday job in 1959, 40 horse-drawn drays still delivered milk in the Dublin area. His first real job was selling ice cream to shops. Not that it was a year-round business: some winters the refrigerated containers were lifted clean off the lorries, so the vehicles could be hired out for coal deliveries.

The ice-cream business had begun as an adjunct to the dairy, in 1926. Later the operations were split. HB Ice Cream eventually became part of Unilever – the multinational group whose brands include Persil washing powder, Birds Eye frozen food and CK One perfume – growing to hold 80 per cent of the domestic ice-cream market.

In the yard of the factory now closing down, Paul Mulhern shows me an outhouse that clearly started life as a stable. It reminds him of the time in the early 1950s, eight years before he joined HB, when he was on a panel of schoolchildren on Radio Éireann’s most popular programme. The School Around The Corner had come to nearby Milltown, where Paul was a pupil at the local national school. The presenter Paddy Crosbie interviewed the children, who had to sing a song, give a recitation or tell a funny story, usually of the my-granny-fell-down-the-stairs-and-we-all-laughed variety.

When Paul’s turn came he started to tell a tale his father had told him on the way to the programme. “I didn’t really understand it, but he said it would be OK. I think he’d had a pint or two.” The story was hardly funny. The nine-year-old told how he had seen a horse bolt and fall into a hole in the road, where it had to be destroyed. Crosbie’s attention was momentarily distracted by some offstage crisis. “Where they did shoot the horse?” he asked. “In the hole, sir,” Paul piped up helpfully. The nation erupted. Nothing quite like it had ever been heard on Radio Éireann. “I remember my mother blushing over it,” says Mulhern. “She’ s still embarrassed half a century later.”

HB stands for Hughes Brothers and for Hazelbrook, the name of the farmhouse that William Hughes and his wife, Margaret, built in 1896. (It has since been reconstructed in Bunratty folk park, in Co Clare.) A stream called the Hazelbrook runs through the school grounds opposite the dairy. People locally still call it the dairy, although the liquid-milk business is long gone. But it was more than just a dairy or an ice-cream factory. It was a local industry, providing jobs for up to 800 staff, mostly locals from Rathfarnham, Dundrum and Churchtown.

“When I joined, if we needed something we did it ourselves. We built our own horse-drawn drays, the bodies for the electric vans which replaced the horses, and we serviced our own vehicles,” says Mulhern. He points to what remains of a motor body building workshop on the old dairy site. “And we were very early into the telesales business. In the 1960s we took orders by phone – sometimes up to 40 a day – for ice-cream cakes for birthdays and sometimes for weddings, and we delivered them.”

Most travellers have noticed that familiar brands such as Cornetto and Magnum are sold in the UK as Wall’s, in France as Miko and in Greece as Algida. They are international Unilever brands. But there are HB brands that are ours alone: the Golly Bar, who lost his cheeky black face to the politically correct winds of change, the Brunch and, of course, the pint brick (all of which will continue to be made here, in a venture with Lakeland Dairies).

The brick, the block of ice cream, was the mainstay of Sunday dinner – we didn’t mess about with lunch then – served with a tin of fruit cocktail in good times. “Bring home a brick after Mass,” the advertising slogan said, and we did. We remain faithful to the block of HB after the rest of the world has moved on.

Mulhern, who rose through the ranks to become a regional sales manager for Unilever Bestfoods Ireland, had another life outside HB. He ran for the Labour Party in two local elections and one general election, in 1979. All he will say about that is: “I didn’t lose my deposit the last time.”

He was more successful managing other people’s campaigns. He was one of Mary Robinson’s directors of elections when she won the presidency in 1990, and he is proud of that. Proud too of getting his man, Mervyn Taylor, elected in Dublin South-West in 1981 and every election thereafter until his retirement, of getting two Labour seats in 1992, and of Taylor’s role in the Cabinet as a reforming minister for equality and law reform. And the subsequent success of the divorce referendum.

Taylor recalls one long and gruelling but ultimately successful count. “A group of us [Labour party workers\] sought refuge in a pub near the RDS count centre. Outside, in the hot June sunshine, I expressed a mournful longing for a Feast” – an HB ice cream – “to which I was, and still am, partial. Miraculously, at that moment, a huge HB van drove by. Paul raised his hand commandingly; the driver opened the refrigerated door and presented us with a box of Feasts. Never had ice cream tasted so good . . . . In that same election, Paul proved as adept at garnering votes as garnering ice cream.”

Mulhern’s retirement from the day job coincides with the plant’s closure at the end of August. “There are hundreds of other lives intertwined with the life and death of HB in Rathfarnham, families raised, like mine, sometimes two and three generations from the same family who worked for the dairy,” he says. “I’m proud of being part of it. Other industries will come along, other skills will develop and prosper, and in time be replaced. Few will be so closely rooted in the produce of the land and the ingenuity of its workers and be so missed.”

The end of an era Frozen out by market forces

Even though HB is Ireland’s leading ice-cream brand, the company says it no longer makes sense to produce ice cream at its Rathfarnham plant. Ice-cream consumption generally is falling, as consumer tastes move towards eating fewer but more expensive ice-cream products.

In one sense the HB plant is both too big and too small. It is too big for the “local products” – blocks of HB ice cream, Golly Bars, Brunches and other brands made just for Ireland – and too small to produce economically international lines such as Magnum and Cornetto for export.

It was not always so. Between 1924, when ice-cream production began, and 1964, when the founding Hughes family sold the company to W. R. Grace & Co, a US multinational, it was protected by tariffs.

In 1968, the two major dairies in Dublin, Hughes Brothers and Premier, did a historic swap. Premier took over Hughes Brothers’ milk business and HB got Premier’s ice-cream trade, ending up with 80 per cent of the local market. A virtually new factory, on the old Rathfarnham site, became one of Europe’s most efficient ice-cream plants, with capacity far in excess of local demand. The answer was exports, particularly to Britain.

The Dutch-English Unilever, which needed to protect its position in the UK ice-cream market, bought HB in 1973. Unilever had good reason to fear Grace on its doorstep.

HB, with a brand new Irish plant, could cause it difficulties in the European market.

Tariff barriers were melting. In 1973 Ireland and Britain joined the EEC, now the EU, and HB had new opportunities on its doorstep. The agriculture subsidies for milk would keep costs down.

The HB ice-cream plant has been winding down since late last year, and the last of its 175 workers will leave next month. The local favourites will be manufactured under licence by Lakeland Dairies, the Co Cavan-based co-op, and the full range of HB products will continue to be marketed throughout Ireland.

Announcing the closure, Paul Murphy, managing director of Unilever Bestfoods Ireland, said: “The unfortunate reality is that it is no longer possible for an ice-cream manufacturing plant such as ours to compete successfully with larger-scale and more specialist Unilever plants located elsewhere on the continent.”

Thus ends almost 80 years of ice-cream making in south Co Dublin.