-

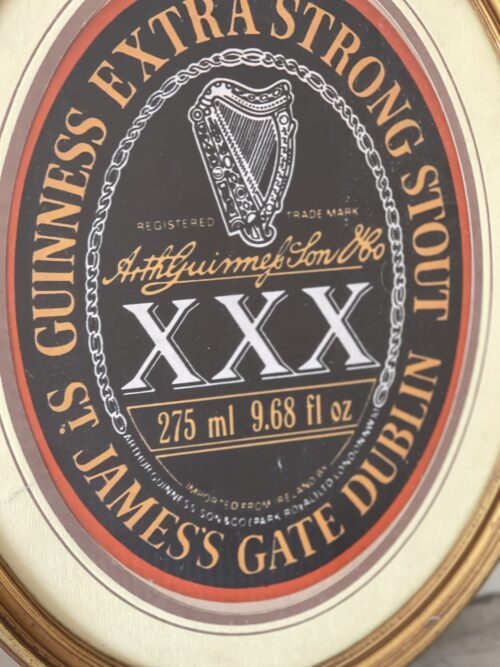

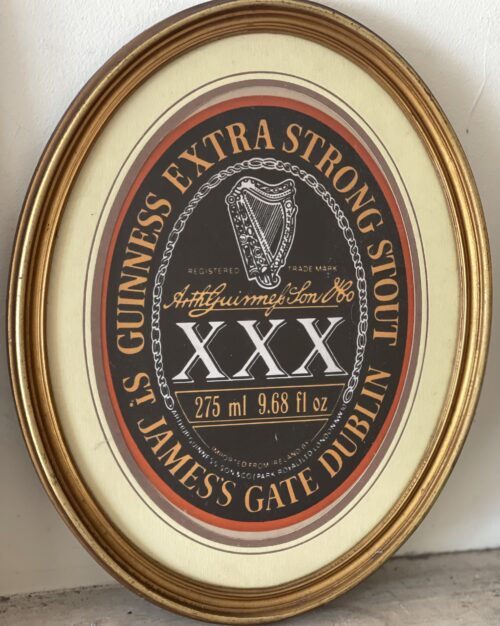

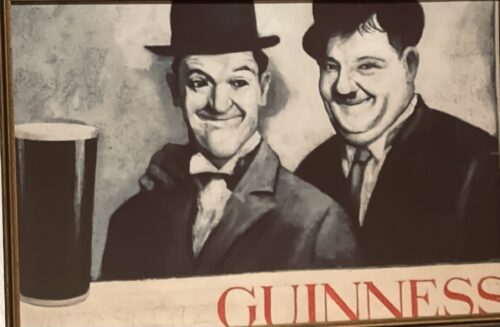

Framed oval shaped print of Guinness XXX label- extra strong stout. Dimensions : 39cm x 30cmDublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm

Framed oval shaped print of Guinness XXX label- extra strong stout. Dimensions : 39cm x 30cmDublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm -

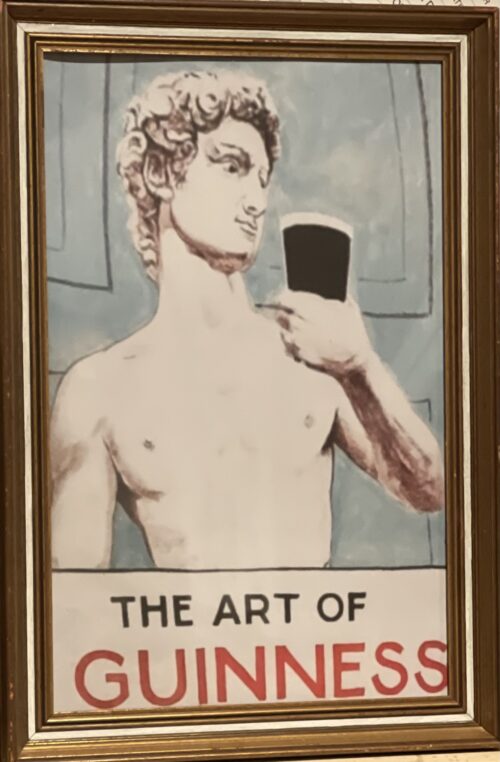

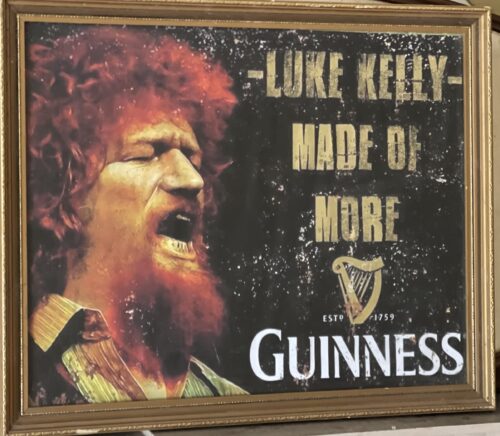

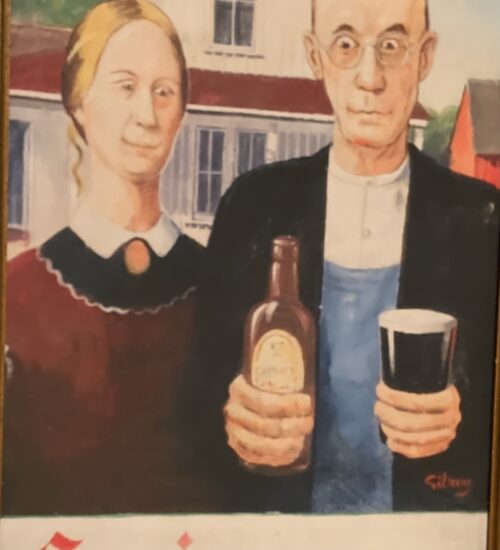

Quite hard to find Guinness Porter on Draught advert with suitably distressed appearance. Dimensions : 32cm x 40cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm

Quite hard to find Guinness Porter on Draught advert with suitably distressed appearance. Dimensions : 32cm x 40cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm -

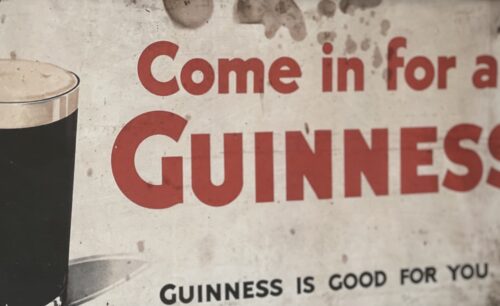

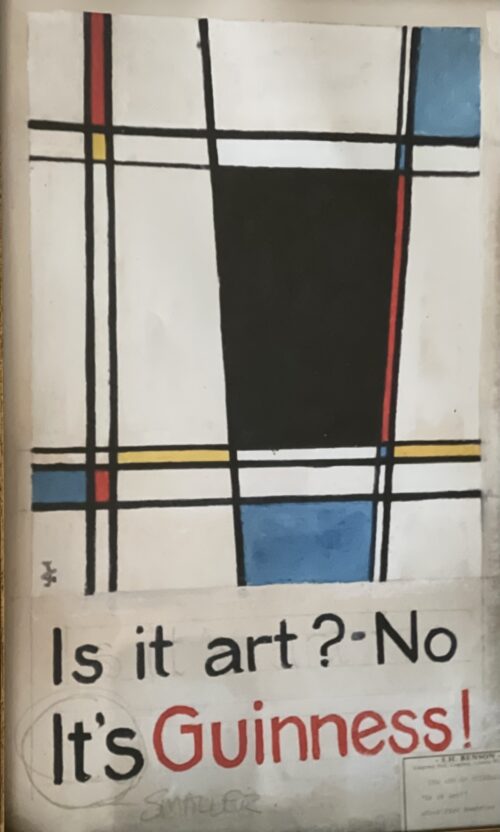

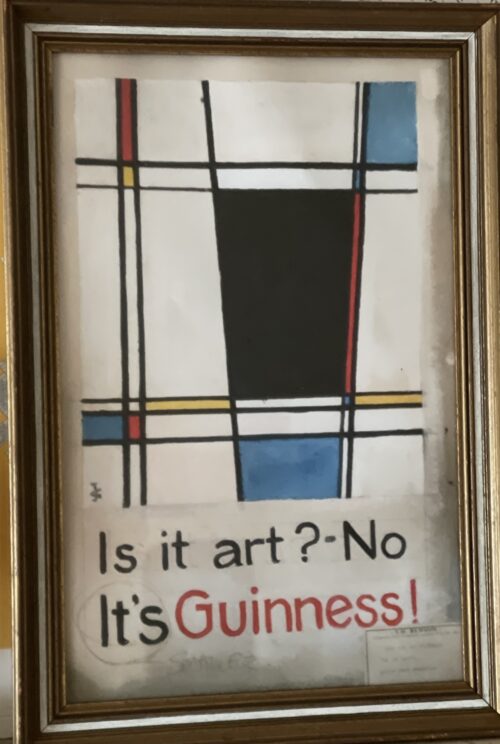

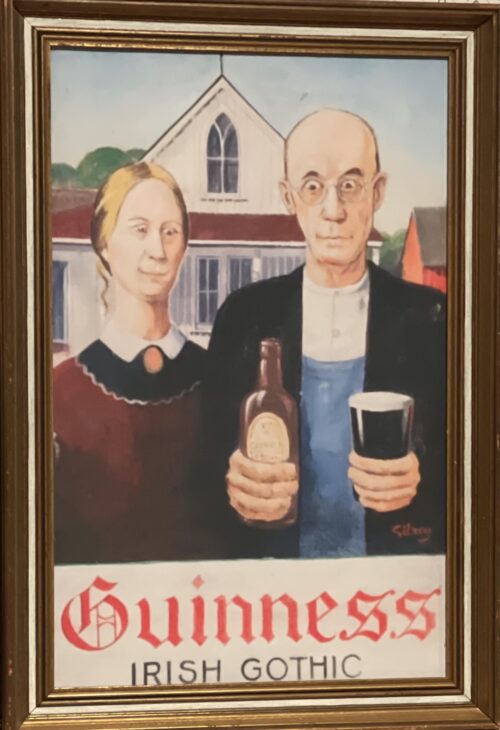

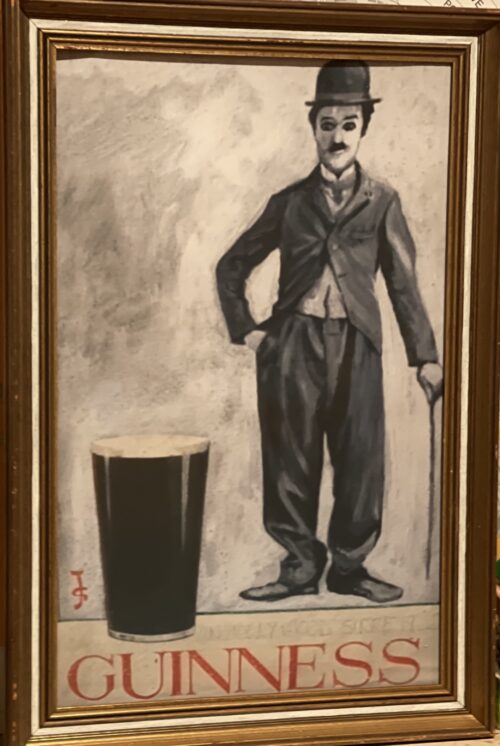

Vintage type come in for a Guinness advert with suitably distressed appearance. Dimensions : 23cm x 40cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm

Vintage type come in for a Guinness advert with suitably distressed appearance. Dimensions : 23cm x 40cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm -

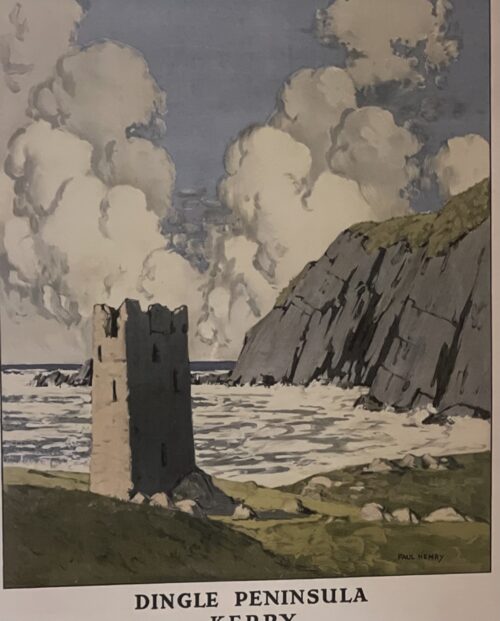

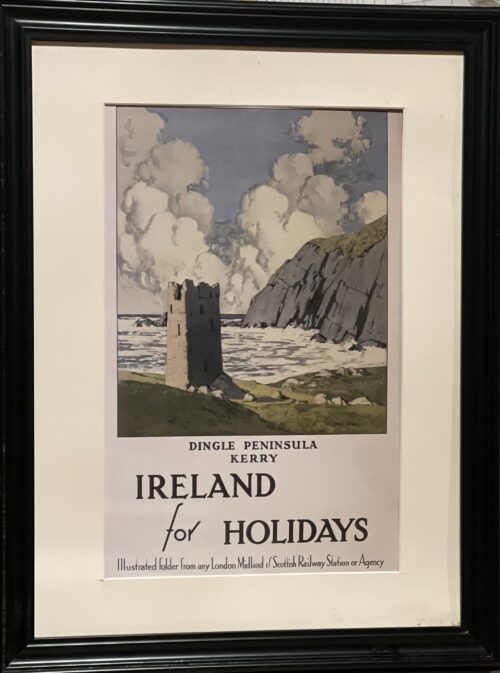

52cm x 44cm The London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) was a British railway company. It was formed on 1 January 1923 under the Railways Act of 1921,which required the grouping of over 120 separate railways into four. The companies merged into the LMS included the London and North Western Railway, Midland Railway, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (which had previously merged with the London and North Western Railway on 1 January 1922), several Scottish railway companies (including the Caledonian Railway), and numerous other, smaller ventures. Besides being the world's largest transport organisation, the company was also the largest commercial enterprise in the British Empire and the United Kingdom's second largest employer, after the Post Office. In 1938, the LMS operated 6,870 miles (11,056 km) of railway (excluding its lines in Northern Ireland), but its profitability was generally disappointing, with a rate of return of only 2.7%. Under the Transport Act 1947, along with the other members of the "Big Four" British railway companies (Great Western Railway, London and North Eastern Railway and Southern Railway), the LMS was nationalised on 1 January 1948, becoming part of the state-owned British Railways. The LMS was the largest of the Big Four railway companies serving routes in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The LMS's commercial success in the 1920s resulted in part from the contributions of English painter, Norman Wilkinson. In 1923, Wilkinson advised Superintendent of Advertising and Publicity of the LMS, T.C Jeffrey, to improve rail sales and other LMS services by incorporating fine art into the design of their advertisement posters. In this time, fine art already had a distinguished association in Europe and North America with good taste, longevity and quality.[26] Jeffrey wanted LMS’ commercial image to align with these qualities and therefore accepted Wilkinson's advice.[27] For the first series of posters, Wilkinson personally invited 16 of his fellow alumni from the Royal Academy of London to take part. In letter correspondence, Wilkinson outlined the details of the LMS proposal to the artists.The artist fee for each participant was £100. The railway poster would measure 50 X 40 inches. In this area, the artist's design would be reproduced as a photolithographic print on double royal satin paper, filling 45 X 35 inches. The mass-produced posters were pasted inside railway stations in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. LMS decided the subject advertised, but choices of style and approach were left to the artist's discretion. LMS’ open design brief resulted in a collection of posters that reflected the large capacity of destinations and experiences available with the transport organisation.For the Irish Free State, Wilkinson designed a poster in 1927 encouraging the public to avail of the LMS ferry and connecting boat trains to Ireland. For this promotion, Wilkinson's design was accompanied with four posters of Ireland by Belfast modernist painter, Paul Henry. The commercial success of Wilkinson and Jeffrey's collaboration manifested between 1924 and 1928, with public sale of 12,000 railway posters.Paul Henry's 1925 poster depicting the Gaeltacht region of Connemara in County Galway proved most commercially popular, with 1,500 sales. Paul Henry (11 April 1876 – 24 August 1958) was an Irish artist noted for depicting the West of Ireland landscape in a spare Post-Impressioniststyle. Henry was born at 61 University Road, Belfast, Ireland, the son of the Rev Robert Mitchell Henry, a Baptist minister (who later joined the Plymouth Brethren), and Kate Ann Berry. Henry began studying at Methodist College Belfast in 1882 where he first began drawing regularly. At the age of fifteen he moved to the Royal Belfast Academical Institution.He studied art at the Belfast School of Art before going to Paris in 1898 to study at the Académie Julian and at Whistler's Académie Carmen. He married the painter Grace Henry in 1903 and returned to Ireland in 1910. From then until 1919 he lived on Achill Island, where he learned to capture the peculiar interplay of light and landscape specific to the West of Ireland. In 1919 he moved to Dublin and in 1920 was one of the founders of the Society of Dublin Painters, originally a group of ten artists. Henry designed several railway posters, some of which, notably Connemara Landscape, achieved considerable sales.He separated from his wife in 1929. His second wife was the artist Mabel Young. In the 1920s and 1930s Henry was Ireland's best known artist, one who had a considerable influence on the popular image of the west of Ireland. Although he seems to have ceased experimenting with his technique after he left Achill and his range is limited, he created a large body of fine images whose familiarity is a testament to its influence. Henry's use of colour was affected by his red-green color blindness.He lost his sight during 1945 and did not regain his vision before his death. A commemorative exhibition of Henry's work was held at Trinity College, Dublin, in 1973 and the National Gallery of Ireland held a major exhibition of his work in 2004. A painting by Henry was featured on an episode of the BBC's Antiques Roadshow, broadcast on 12 November 2006. The painting was given a value of approximately £40,000–60,000 by the roadshow. However, due to the buoyancy of the Irish art market at that time, it sold for €260,000 on 5 December 2006 in James Adams' and Bonhams' joint Important Irish Art sale. He died at his home at 1 Sidmonton Square, Bray, County Wicklow, and was survived by his wife, Mabel.

52cm x 44cm The London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) was a British railway company. It was formed on 1 January 1923 under the Railways Act of 1921,which required the grouping of over 120 separate railways into four. The companies merged into the LMS included the London and North Western Railway, Midland Railway, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (which had previously merged with the London and North Western Railway on 1 January 1922), several Scottish railway companies (including the Caledonian Railway), and numerous other, smaller ventures. Besides being the world's largest transport organisation, the company was also the largest commercial enterprise in the British Empire and the United Kingdom's second largest employer, after the Post Office. In 1938, the LMS operated 6,870 miles (11,056 km) of railway (excluding its lines in Northern Ireland), but its profitability was generally disappointing, with a rate of return of only 2.7%. Under the Transport Act 1947, along with the other members of the "Big Four" British railway companies (Great Western Railway, London and North Eastern Railway and Southern Railway), the LMS was nationalised on 1 January 1948, becoming part of the state-owned British Railways. The LMS was the largest of the Big Four railway companies serving routes in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The LMS's commercial success in the 1920s resulted in part from the contributions of English painter, Norman Wilkinson. In 1923, Wilkinson advised Superintendent of Advertising and Publicity of the LMS, T.C Jeffrey, to improve rail sales and other LMS services by incorporating fine art into the design of their advertisement posters. In this time, fine art already had a distinguished association in Europe and North America with good taste, longevity and quality.[26] Jeffrey wanted LMS’ commercial image to align with these qualities and therefore accepted Wilkinson's advice.[27] For the first series of posters, Wilkinson personally invited 16 of his fellow alumni from the Royal Academy of London to take part. In letter correspondence, Wilkinson outlined the details of the LMS proposal to the artists.The artist fee for each participant was £100. The railway poster would measure 50 X 40 inches. In this area, the artist's design would be reproduced as a photolithographic print on double royal satin paper, filling 45 X 35 inches. The mass-produced posters were pasted inside railway stations in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. LMS decided the subject advertised, but choices of style and approach were left to the artist's discretion. LMS’ open design brief resulted in a collection of posters that reflected the large capacity of destinations and experiences available with the transport organisation.For the Irish Free State, Wilkinson designed a poster in 1927 encouraging the public to avail of the LMS ferry and connecting boat trains to Ireland. For this promotion, Wilkinson's design was accompanied with four posters of Ireland by Belfast modernist painter, Paul Henry. The commercial success of Wilkinson and Jeffrey's collaboration manifested between 1924 and 1928, with public sale of 12,000 railway posters.Paul Henry's 1925 poster depicting the Gaeltacht region of Connemara in County Galway proved most commercially popular, with 1,500 sales. Paul Henry (11 April 1876 – 24 August 1958) was an Irish artist noted for depicting the West of Ireland landscape in a spare Post-Impressioniststyle. Henry was born at 61 University Road, Belfast, Ireland, the son of the Rev Robert Mitchell Henry, a Baptist minister (who later joined the Plymouth Brethren), and Kate Ann Berry. Henry began studying at Methodist College Belfast in 1882 where he first began drawing regularly. At the age of fifteen he moved to the Royal Belfast Academical Institution.He studied art at the Belfast School of Art before going to Paris in 1898 to study at the Académie Julian and at Whistler's Académie Carmen. He married the painter Grace Henry in 1903 and returned to Ireland in 1910. From then until 1919 he lived on Achill Island, where he learned to capture the peculiar interplay of light and landscape specific to the West of Ireland. In 1919 he moved to Dublin and in 1920 was one of the founders of the Society of Dublin Painters, originally a group of ten artists. Henry designed several railway posters, some of which, notably Connemara Landscape, achieved considerable sales.He separated from his wife in 1929. His second wife was the artist Mabel Young. In the 1920s and 1930s Henry was Ireland's best known artist, one who had a considerable influence on the popular image of the west of Ireland. Although he seems to have ceased experimenting with his technique after he left Achill and his range is limited, he created a large body of fine images whose familiarity is a testament to its influence. Henry's use of colour was affected by his red-green color blindness.He lost his sight during 1945 and did not regain his vision before his death. A commemorative exhibition of Henry's work was held at Trinity College, Dublin, in 1973 and the National Gallery of Ireland held a major exhibition of his work in 2004. A painting by Henry was featured on an episode of the BBC's Antiques Roadshow, broadcast on 12 November 2006. The painting was given a value of approximately £40,000–60,000 by the roadshow. However, due to the buoyancy of the Irish art market at that time, it sold for €260,000 on 5 December 2006 in James Adams' and Bonhams' joint Important Irish Art sale. He died at his home at 1 Sidmonton Square, Bray, County Wicklow, and was survived by his wife, Mabel. -

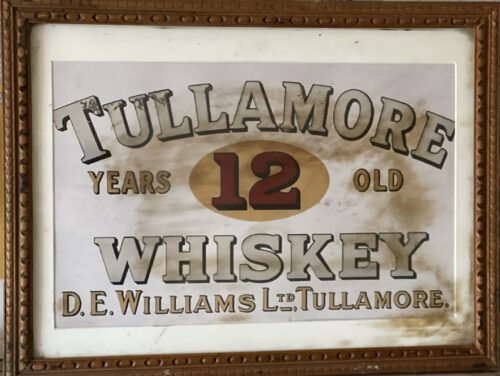

55cm x 45cm Banagher Co Offaly Tullamore D.E.W. is a brand of Irish whiskey produced by William Grant & Sons. It is the second largest selling brand of Irish whiskey globally, with sales of over 950,000 cases per annum as of 2015.The whiskey was originally produced in the Tullamore, County Offaly, Ireland, at the old Tullamore Distillery which was established in 1829. Its name is derived from the initials of Daniel E. Williams (D.E.W.), a general manager and later owner of the original distillery. In 1954, the original distillery closed down, and with stocks of whiskey running low, the brand was sold to John Powers & Son, another Irish distiller in the 1960s, with production transferred to the Midleton Distillery, County Cork in the 1970s following a merger of three major Irish distillers.In 2010, the brand was purchased by William Grant & Sons, who constructed a new distillery on the outskirts of Tullamore. The new distillery opened in 2014, bringing production of the whiskey back to the town after a break of sixty years.

55cm x 45cm Banagher Co Offaly Tullamore D.E.W. is a brand of Irish whiskey produced by William Grant & Sons. It is the second largest selling brand of Irish whiskey globally, with sales of over 950,000 cases per annum as of 2015.The whiskey was originally produced in the Tullamore, County Offaly, Ireland, at the old Tullamore Distillery which was established in 1829. Its name is derived from the initials of Daniel E. Williams (D.E.W.), a general manager and later owner of the original distillery. In 1954, the original distillery closed down, and with stocks of whiskey running low, the brand was sold to John Powers & Son, another Irish distiller in the 1960s, with production transferred to the Midleton Distillery, County Cork in the 1970s following a merger of three major Irish distillers.In 2010, the brand was purchased by William Grant & Sons, who constructed a new distillery on the outskirts of Tullamore. The new distillery opened in 2014, bringing production of the whiskey back to the town after a break of sixty years.Mick The Miller,as featured in this iconic advert, was the most famous greyhound of all time. He was born in 1926 in the village of Killeigh, County Offaly, Ireland at Millbrook House(only 5 miles from Tullamore), the home of parish curate, Fr Martin Brophy. When he was born Mick was the runt of the litter but Michael Greene, who worked for Fr Brophy, singled the little pup out as a future champion and insisted that he be allowed to rear him. With constant attention and regular exercise Mick The Miller developed into a racing machine. His first forays were on local coursing fields where he had some success but he showed his real talent on the track where he won 15 of his first 20 races.

.jpg)

In 1929 Fr Brophy decided to try Mick in English Greyhound Derby at White City, London. On his first trial-run, Mick equalled the track record. Then, in his first heat, he broke the world record, becoming the first greyhound ever to run 525 yards in under 30 seconds. Fr Brophy was inundated with offers and sold him to Albert Williams. Mick went on to win the 1929 Derby. Within a year he had changed hands again to Arundel H Kempton and won the Derby for a second time.

Over the course of his English career he won 36 of his 48 races, including the Derby (twice), the St Leger, the Cesarewitch, and the Welsh Derby. He set six new world records and two new track records. He was the first greyhound to win 19 races in a row. Several of his records went unbroken for over 40 years. He won, in total, almost £10,000 in prizemoney. But he also became the poster-dog for greyhound racing. He was a celebrity on a par with any sports person, muscisian or moviestar. The more famous he became, the more he attracted people to greyhound racing. Thousands thronged to watch him, providing a huge boost to the sport. It is said that he actually saved the sport of greyhound racing.