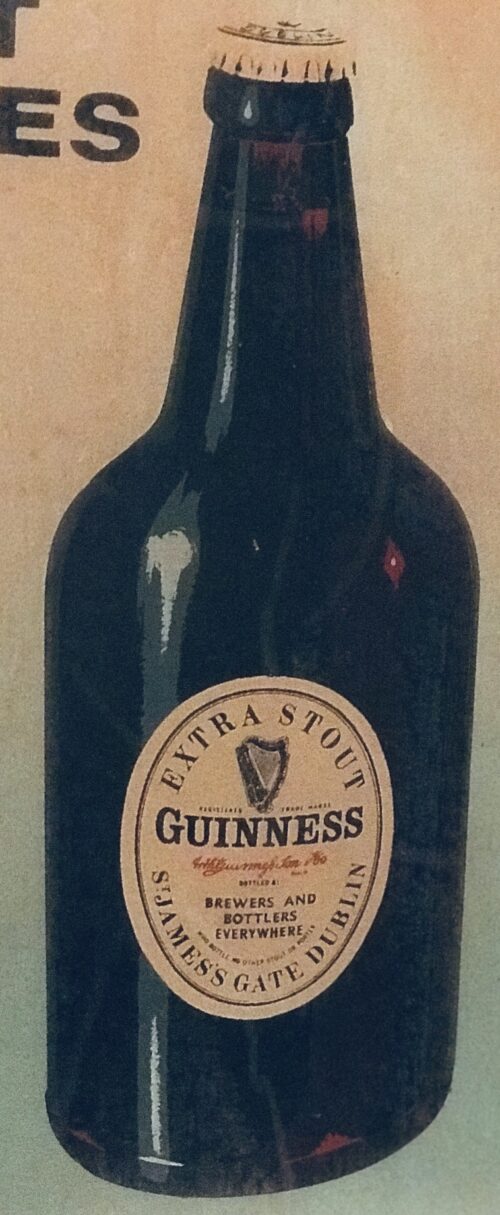

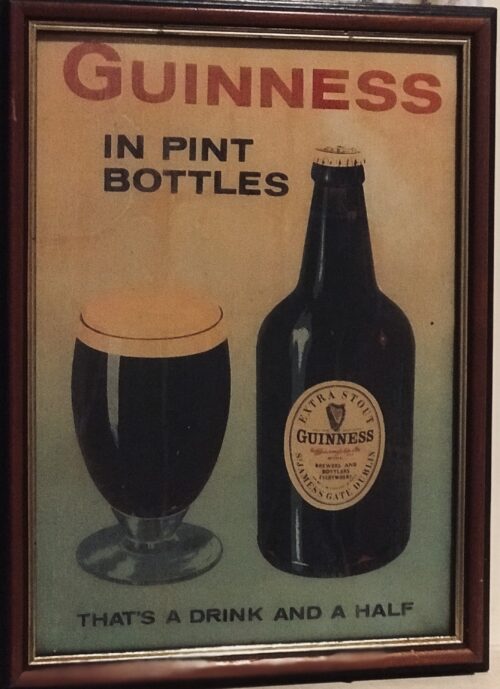

Lovely Guinness print depicting the famous Guinness barge 'The Miranda" plus various old Guinness bottle labels.

Origins : Dublin Dimensions :28cm x 60cm Glazed

The Guinness brewing concern had substantial maritime resources to support distribution of the famous beer. In addition the family spent a lot of their leisure on a range of fabulous pleasure craft. Initially the reach of the brewing concern expanded from 1790 thanks to the commencement of the Irish canal system. Barge transport enabled distribution of their beer from Dublin and import of malt from all parts of the country. This led to grain depots; maltings and beer distribution depots being situated on canal banks and ultimately brought about the decline of the tiny country breweries that served the smaller towns. In order to serve the UK market beer was shipped from Dublin port. Initially quantities were small, but from 1877 when the brewery at St James’s gate expanded considerably a jetty was built at Victoria quay upstream on the Liffey and barges or more correctly lighters carried the beer from the brewery to ships in the port. From 1913 Guinness became ship-owners and used their own cross channel fleet to serve Liverpool, Manchester, London and Bristol.

Guinness barges

The fleet of Liffey barges were in two main groups built in 1877 – 1892 and replaced in the 1920s. They ceased in 1961 when trucks replaced them and mostly went on to serve as sand barges working on Lough Neagh. They were too big for the Irish canal system and never served on canals except to access Lough Neagh. Canal barges served depots at Ballinasloe, Limerick, Athy and all points on the canal and Shannon navigation system. They were loaded at the Grand Canal Harbour or at the adjoining Guinness Harbour which was accessed through a channel under a lifting bridge known as the

Rupee Bridge. Even shipwrecks have lighter moments. This ballad refers to the

Vartry, one of the fleet of large steam barges or lighters which were used to transport Guinness stout from the Brewery wharf at Victoria Quay on the Liffey, down river to ships at Custom House Quay whence it was transported to Britain. The barges operated until 1963. The

Vartry was built in the Liffey Dockyard in 1902 and apparently sank in 1907 but was raised shortly afterward. The ballad was collected by Colm O’Lochlainn and published in More Irish Street ballads.

In another incident the Guinness lighter barge

Docena sank near the Custom House on 18-8-1927. The skipper B. Holcroft describes meeting a sudden squall as he passed under Butt Bridge. He discovered he was in danger due to the amount of water shipped. He made for the pier but the mooring ropes had only been fixed when the barge sank. The men aboard scrambled ashore without injury. Only 167 of the cargo of 200 hogsheads of Guinness were salved. Two days later the barge was raised by the Dublin Port and Docks Board and found to be undamaged.

It was the good ship Vartry

That sailed the sweet Liffee,

And the skipper had taken the casks aboard,

A goodly companee.

Blue were the labels, and azure blue,

Proclaiming double x,

But neither the skipper nor the crew

Had dreamt of storms or wrecks.

Now as she steamed by the Ha’penny Bridge,

The engine raised a row,

While a cloud no bigger than a midge

Loomed up on the starboard bow.

And as they steered by Aston’s quay,

The lookout man grew pale,

“I feared we’d not escape,” says he,

“McBirney’s summer sale”.

And ere they reached the Customs House,

Down in a wild vortex,

The Vartry plunged, the cause was plain,

She’d too much Double X.

All you who drink of James Gate,

(No matter what your sex),

Take warning by the Vartry’s fate,

Thro’ too much Double X.

| Name |

Built |

Notes |

Disposed |

| Lagan |

Harland & Wolfe 1877 |

|

Sunk 1970s at Sandy Bay, Lurgan as foundations at Scotts |

| Shannon |

Allsop, Preston 1883 |

Double ended and could proceed forwards or backwards |

Sold and sank off Balbriggan |

| Liffey |

Ross & Walpole, Dublin 1888 |

Commandeered in WW1 for service in France! |

Wrecked at Skane flat Lough Neagh still visible |

| Lee |

Ross & Walpole, Dublin 1889 |

|

|

| Boyne |

Ross & Walpole, Dublin 1891 |

Commandeered in WW1 for service in France |

Embedded in Hutchesons sand quay |

| Slaney |

Ross & Walpole, Dublin 1892 |

|

Sunk at Tarmac as foundations for quay |

| Siur |

Ross & Walpole, Dublin 1892 |

|

Long of Cork worked on river Slaney |

| Foyle |

Ross & Walpole, Dublin 1897 |

|

Sank on rocks near Lurgan 1950s |

| Moy |

Ross & Walpole, Dublin 1897 |

|

J Tinsley Belfast |

| Vartry |

Ross & Walpole 65/67 North Wall 1902 |

|

James Transport London, then Belfast |

| Dodder |

Ross & Walpole, Dublin 1911 |

|

Broken at Lees Carlingford 1946 |

| Tolka |

Ross & Walpole, Dublin 1913 |

|

Hamilton Gabbie Comber co Down |

| Docena |

Built in Norwich Bought UK 1920 |

Sank at Custom House but raised |

Scrapped 1950 |

| Farmleigh |

Vickers (Ireland) Alexandra basin 1927 |

Sold to RN 1938 |

Used at Scapa Flow |

| Knockmaroon |

Vickers (Ireland) Alexandra basin 1929 |

Sold 1938 |

John Hunt, Leeds |

| Chapelizod |

Vickers (Ireland) Alexandra basin 1929 |

Sold 1938 |

Blown up on Lough Neagh 1970 |

| Fairyhouse |

Vickers (Ireland) Alexandra basin 1929 |

Sold To RN 1938 |

Worked on Humber and was at Dunkirk evacuation |

| Castleknock |

Vickers (Ireland) Alexandra basin 1929 |

Sold 1961 |

Blown up on Lough Neagh 1970 |

| Clonsilla |

Vickers (Ireland) Alexandra basin 1930 |

Sold 1961 |

Sank in Lough Neagh during a storm in 60 feet depth of water |

| Killiney |

Vickers (Ireland) Alexandra basin 1930 |

Sold 1961 |

Sunk 1970s at Ballyginiff point as foundations |

| Sandyford |

Vickers (Ireland) Alexandra basin 1931 |

Sold 1961 |

|

| Howth |

Vickers (Ireland) Alexandra basin 1931 |

Sold 1961 |

|

| Seapoint |

Vickers (Ireland) Alexandra basin 1931 |

Sold 1961 |

|

Guinness Company Ships

From 1913 when Dublin port was paralysed by the industrial unrest Guinness secured their trade by shipping most of their beer to the UK in their own fleet of coasters. Bottling plants in Liverpool and Runcorn served the UK and African export markets. The ships also served bottlers in London and Bristol by sea. Container and roll on roll off tankers replaced the ship’s tanks until 1993. Trade now continues using the regular vehicle ferries.

The trade was not without incident. The

Barkley was torpedoed, The

Carrowdore was bombed and the bomb lodged in her rails while the

Miranda struck the East Link Bridge.

The

Lady Patricia was the first ship adapted with beer tanks to carry beer in bulk. These tanks were washed and steam sterilised en route back to Dublin after the beer had been discharged at Runcorn or Liverpool. On one occasion as the

Patricia entered a lock on the Manchester Ship Canal the captain looked over the side and to his horror the lock was filling with frothy tank washings. Someone had started to discharge the rinsings of beer before they had reached the open sea. The authorities were very strict about discharges in the canal which was suffering from serious pollution of all types and was filthy. He had to think quickly and ordered “full ahead on engines, full astern, stop engines” the engines obeyed and the propellers churned up the filthy mud from the bottom of the lock. In the stinking ordure that was disturbed concealed the beer foam and nobody was the wiser.

The task was more advanced another day and the tanks were being steamed. Whatever following wind conditions prevailed the ship was shrouded in clouds of steam as it made its way past the South Stack and out to sea toward Dublin. An aeroplane passing overhead observed this strange sight and promptly reported that the Patricia was on fire and a lifeboat was launched to assist before all was declared safe. The

Miranda had a collision with the East Link toll bridge on the Liffey while outward bound one day. It was thought that her bow thruster had caused her to deviate from her course. More seriously on 10 November 1961 the

Lady Gwendolen ran down the

Freshfield lying at anchor during fog in the Mersey. The incident is widely quoted in Maritime case law. Ironically the

Lady Gwendolen (then called

Paros) was herself rammed and sunk at anchor on 10 November 1979 at Ravenna. The

Lady Patricia was in reserve for the

Miranda Guinness for a few years and only operated when the Miranda was on annual overhaul. This gave an opportunity to be used for film work. When the

Patricia played the part of the emigrant ship in the film

Far and Away the first officer was admonished for daring to appear on the bridge during the important work of filming. He had merely thought it prudent to steer the ship. The

Patricia also played the mail boat in

Hear my Song (1991).

| Name |

Tons |

Built |

Bought from |

Disposed |

| W.M Barkley |

569 |

Ailsa, Troon 1898 |

1913,Kellys, Belfast, |

Torpedoed and sank 1917 |

| Carrowdore |

598 |

Bowling 1914 |

Kellys, 1914 |

Sold to Davidsons Belfast 1952, broken 1959 |

| Clarecastle |

664 |

Bowling 1914 |

Kellys, 1915 |

Sold to Davidsons Belfast 1953, broken 1959 |

| Clareisland |

633 |

Bowling 1915 |

Kellys, 1915 |

Sold, 1931 to Antrim Iron Ore Co and sank near Isle of Man 1939 |

| Guinness |

1151 |

Ailsa Troon, 1931 |

|

Served the Dublin to London trade to 1938, disposed 1963 |

| Lady Grania |

1252 |

Ailsa Troon, 1952 |

|

Sold 1976 renamed Lady Scotia Stranded On Pacific coast of Mexico 1981 |

| Lady Gwendolen |

1166 |

Ardross Dockyard 1953 |

|

Sold 1977 to Cypriot shipping renamed Paros and sank off Nova Scotia 1979 |

| Lady Patricia |

1187 |

Charles Hill Bristol 1962 |

|

Broken April 1993 |

| Miranda Guinness |

1540 |

Charles Hill, 1976 Bristol |

|

Broken April 1993 |

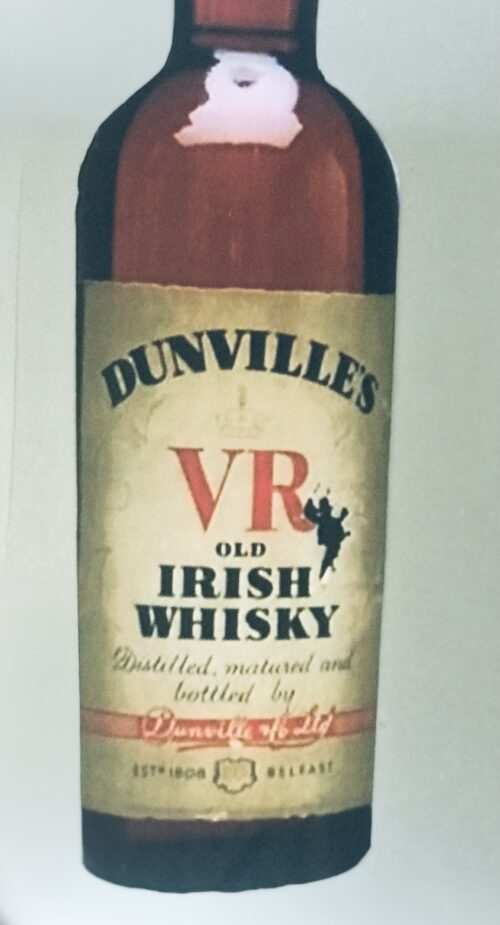

Empty barrels and hogsheads were stacked on the quays both at Custom House and at city quay. Sheltered from view there was a shady world of the Hoggers. This group of vagrants assembled on the dockside around the empties returning from the British market and consumed the dregs ofthe barrels that were available. The barrels were marked with red paint to indicate their contents and this paint or raddle was a paticular red colour. These characters were also known as raddlers as it was suggested that their faces and beards were stained red from the raddle on the casks. The police would disperse them when they became excessively rowdy. Spunkers were a variety on the theme; they drank from overflowing barrels and casks that had frothed over in hot summer weather. Similar groups of woodeners or boilers targeted empty whiskey casks that they scalded with boiling water to extract the last of the spirit from the wood.

Some Yachts owned by the Guinness family

This is an incomplete list of the pleasure craft owned by the Guinness family. They ranged from racing yachts to super luxury steamers and sailing craft and even included sponsoring Jacques Cousteau’s famous

Calypso

| Vessel |

Owner |

Size |

comment |

| Lady Olive |

Lord Ardilaun |

|

Struck Rock in Corrib 7-2-1872, relieved Captain Boycott |

| Medusa II |

Guinness |

627 ton |

1906-1915, sunk as HMY Mollusc off Blyth |

| Sea Huntress |

Loel Guinness |

|

Married Princess Gloria aboard, off Antibes |

| Cetonia |

Edward Cecil |

Schooner |

1880 |

| Ceto |

Edward Guinness |

106 ton |

Entertained Prince Edward at Cowes 1886 accompanied by Mrs Keppel |

| Leander |

Rupert Guinness |

90 foot yawl |

Won King’s Cup at Cowes |

| Atlantis |

Loel Guinness |

216 ton |

|

| Calypso |

Loel Guinness |

330 ton |

In the course of preservation at Brest |

| Fantome |

Arthur Ernest Guinness |

139 ton |

1906-1938 |

| Fantome |

Arthur Ernest Guinness |

Ex Belem |

1921-1951 |

| Fantome |

Arthur Ernest Guinness |

Ex Flying Cloud, four masted |

1938-1951 |

| Rossaura |

Lord Moyne |

1400 ton ex Dieppe |

1933 – 1940, Sank off Torbruk |

| Roussalka |

Lord Moyne |

1400 ton ex Brighton |

1931 -1933, Sank off Killary |

| Amo |

Arthur Ernest Guinness |

Ex ML 482 |

1928-1949, scrapped in Dublin |

| Rob Roy McGregor |

John Guinness (banking family) |

|

|

In the 1880s, yachting became popular among the smart set led by the Prince of Wales. Cowes Week became the focus of lavish entertainment. The Guinness family took to the new fashion with gusto as befitted the new nobility.

In the membership list of the Royal St George Yacht Club for 1924 the overall tonnage of yachts exceeding 5 tons was 3,893 and of this the Guinness family owned 1,538 tons. The Rear Commodore was the Hon A.E Guinness who personally owned 1,076 tons. One of his craft was a hydroplane

Oma II. The most magnificent was

Fantome II. The 611 ton, barque, originally named

Belem was built at Chantenay sur Loire in 1896 by the Dubigeon shipbuilding company. She was ordered by the French industrialist Fernand Crouan to bring cocoa from Brazil for the Menier chocolate factory. She continued this trade until 1914 when she was purchased by the Duke of Westminster who refitted her as a luxury yacht. Arthur Edward Guinness acquired her in 1921 and renamed her

Fantome II. In 1921 he took his daughters Aileen, Maureen and Oonagh on a 40,000 mile cruise around the world. Decommissioned in 1939, the Belem was abandoned in a creek at the Isle of Wight. An Italian foundation restored her as a sail training vessel in 1952 and she was bought by the Belem Foundation, sponsored by the French bank Caisse d’Epargne in 1980. Since then the Belem has been based at Nantes as the last major French sailing ship. In 2005 she visited Waterford during the 2005 Tall Ships race and was photographed by John Colfer of Dunmore East. The keel of the

Fantome was laid in Livorno, Italy during the First World War. Designed initially as a destroyer, the hull lay unfinished. The Duke of Westminster ordered her completion as a 1270 ton yacht, Flying Cloud, in 1927. About 1938 Arthur Ernest Guinness acquired her. On his death in 1949 Fantome was sold in Seattle but remained abandoned there for fourteen years. Aristotle Onassis purchased her as a wedding gift for Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco, but she lay abandoned at Kiel. She became a cruise ship in 1969 and operated for Windjammer cruises in the Caribbean. The

Fantome sank off Key West during a Hurricane on October 27 1998. Captain March and all 30 West Indian crew were lost but passengers had disembarked when their trip was cancelled due to the bad weather.

Amo II was converted in 1928 by A.E. Guinness and brought to Cong. She was built in 1917 by Levis in Quebec as an anti-submarine boat

ML 482. A.E. Guinness also bought her sister the

ML 575 which he called

Amo. The

Amo II sailed Lough Corrib as a pleasure boat before falling into disuse. She became the last boat to sail through Galway’s Eglinton canal in 1954 before low bridges replaced the swing bridges and obstructed the waterway. Though refitted in DúnLaoghaire it was not sold and was scrapped by Hammond Lane Company in 1954. The other

Amo may have been used for spare parts and may lie submerged at Cong. The name Amo (Latin I love) is derived from the initials of his daughters, Aileen, Maureen and Oonagh

The 1400-ton yacht

Roussalka sank on 1

st September off Killary Harbour. The vessel under captain Laidlaw had landed some guests at Killary bound for Ashford Castle. When the vessel was leaving the inlet he took a wrong course and struck Bloodslate rock near Fraebl Island. All aboard, including Lord Moyne and crew of 25, escaped without injury though she sank in 11 minutes. Originally named the Brighton, she was built by the Denny yard on the Clyde in 1903 as a railway steamer. Bought by Lord Moyne in 1930 she was refitted. A 500-ton oil tank was installed to enable her to cross the Pacific. Her turbines were replaced by diesels and one of her funnels was removed. Within a month Lord Moyne obtained the

Rosaura, another Newhaven to Dieppe channel steamer that was lying disused at Newhaven. Built by Fairfield at Govan in 1905, the 1210 ton, vessel was named

Dieppe IV. During WW1 she served as a troopship and hospital ship. In September 1933 she was sold to Lord Moyne and converted to an ocean going yacht. The 1933 refit included replacement of the Parsons steam turbines with Atlas Diesels, a funnel and third screw were removed and the extra accommodation increased her registered capacity to 1538 tons. Her appearance became uncannily like the

Roussalka. In August 1934 Lord Moyne entertained the Prince of Wales and Mrs Simpson on a two week Mediterranean cruise from Spain to Genoa to escape the attentions of the press. The next year Prince Edward became King Edward VIII and abdicated. The

Rosaura was hired by the Admiralty as an armed boarding vessel in November 1939 and was mined and sank off Tobruk on 18 March 1941.

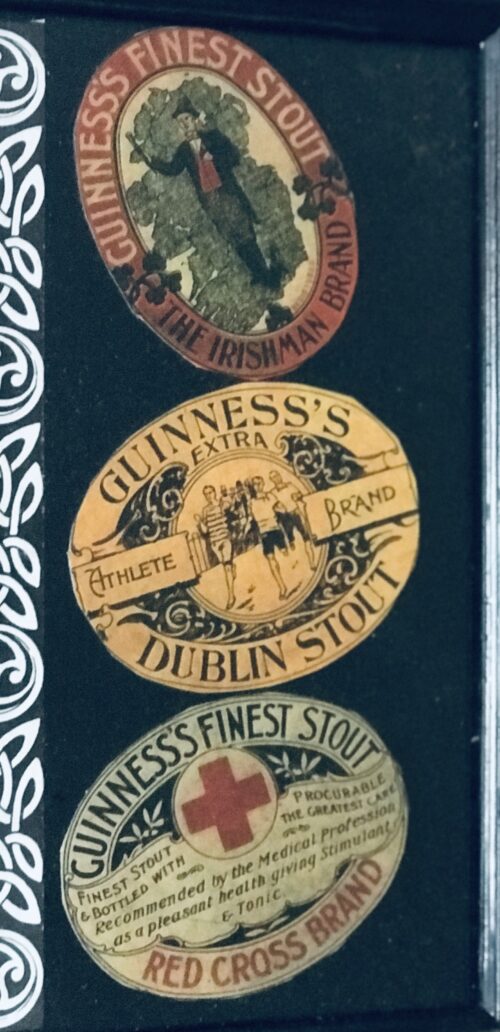

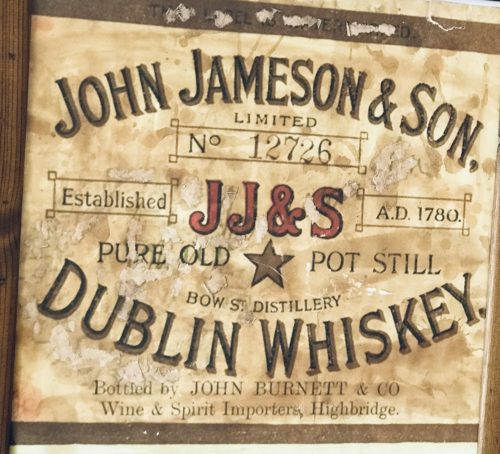

Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer

porter in 1778.

The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.

Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export.

“Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.

Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of

Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.”

Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000

barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.

In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount.

Even though Guinness owned no

public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading.

The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician

William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly

Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known

Student’s t-test.

By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees.

By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill.

The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir

John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor

Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market.

In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world.

Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a

Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the

Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.”

Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973.

In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981.

Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used.

In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter.

Guinness acquired the

Distillers Company in 1986.

This led to a

scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case

Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid.

In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo.

The company merged with

Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form

Diageo.

Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.

The Guinness Brewery Park Royal during demolition, at its peak the largest and most productive brewery in the world.

The Guinness brewery in

Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to

St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin.

Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”.

Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts.

The Irish

Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.

This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the

Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the

Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant.

On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the

Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development.

On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.

Two days later, the

Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with

Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate.

Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.

Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997.

In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing

Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use

isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.

This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now.

Guinness

stout is made from water,

barley, roast malt extract,

hops, and

brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is

pasteurisedand

filtered.

Until the late 1950s Guinness was still

racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.

Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of

isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer.

Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians.

Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO

2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO

2 taste. This step was taken after

Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible.

Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the

widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste.

Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an

original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.

Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of

ruby.

The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes.

Studies claim that Guinness can be

beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘

antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful

cholesterol on the artery walls.”

Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by

Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.

Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.”

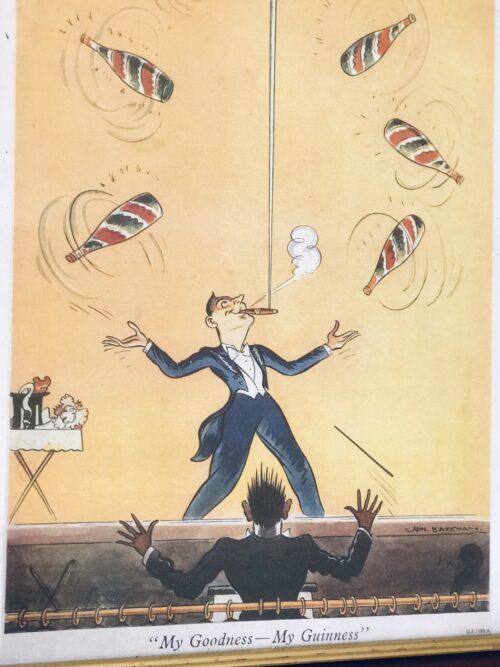

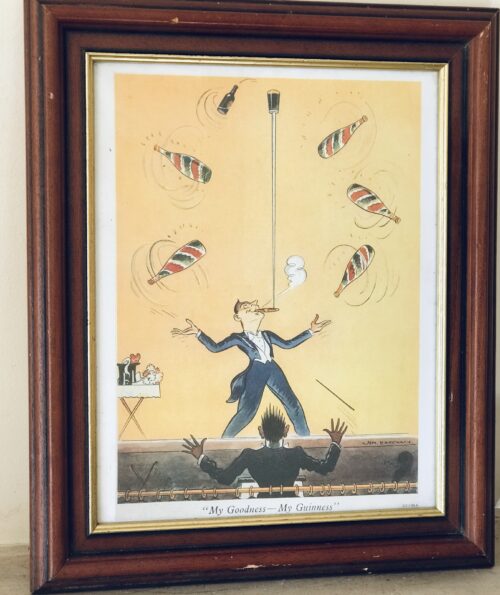

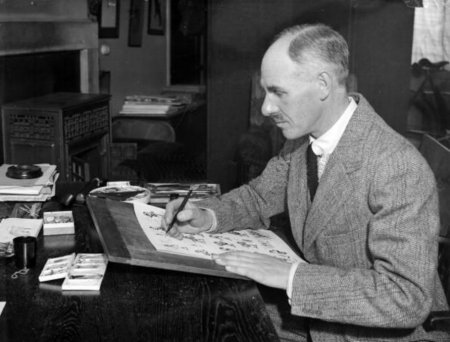

H M Bateman 1887 - 1970

20th century cartoonist and caricaturist

To many admirers of the art of the cartoon, H.M.Bateman is the most original, the most various, the most brilliant – and, indeed, the funniest – genius of his times. Born in 1887, he was already drawing for publication in his early teens. Astonishingly prolific and inventive, everything he saw became material, so that his work can be read as a social history of Britain in the first half of the 20th Century and, to an extraordinary degree, as a kind of autobiography. His family and friends; his trips to the fair, to the seaside, abroad; his passions for the Music Hall, for tap-dancing, for boxing, for fishing, for golf; his desperate experiences in the First World War; his car, his house, his vacuum-cleaner; his triumphs and disasters over many years – all find their way in to his cartoons.

H M Bateman 1887 - 1970

20th century cartoonist and caricaturist

To many admirers of the art of the cartoon, H.M.Bateman is the most original, the most various, the most brilliant – and, indeed, the funniest – genius of his times. Born in 1887, he was already drawing for publication in his early teens. Astonishingly prolific and inventive, everything he saw became material, so that his work can be read as a social history of Britain in the first half of the 20th Century and, to an extraordinary degree, as a kind of autobiography. His family and friends; his trips to the fair, to the seaside, abroad; his passions for the Music Hall, for tap-dancing, for boxing, for fishing, for golf; his desperate experiences in the First World War; his car, his house, his vacuum-cleaner; his triumphs and disasters over many years – all find their way in to his cartoons.

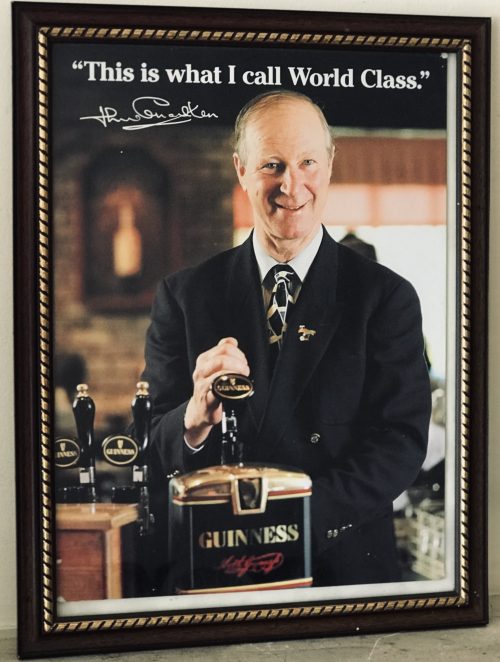

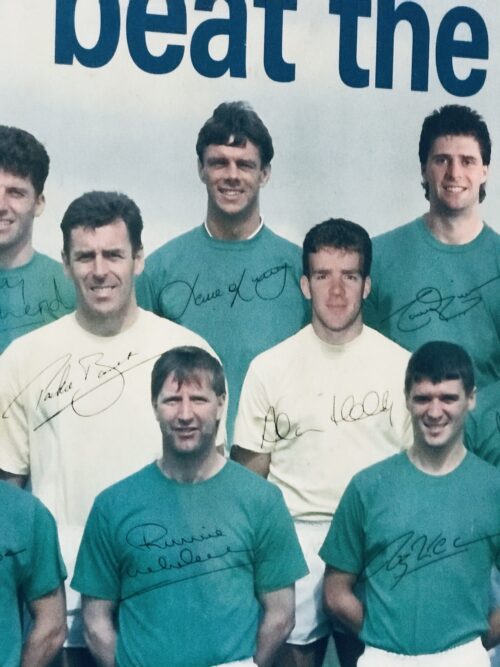

Charlton had beaten late entrant Bob Paisley, a multiple trophy winner, to the FAI hot seat, and his introduction to the gathered press was a million miles away from the carefully staged managed productions of the modern day.

In fact, it almost turned into an impromptu David Haye and Tony Bellew pre-match fight when Charlton challenged hardened journalist and ex-international Eamon Dunphy’s line of questioning. That relationship turned increasingly sour as time went by.

Charlton had beaten late entrant Bob Paisley, a multiple trophy winner, to the FAI hot seat, and his introduction to the gathered press was a million miles away from the carefully staged managed productions of the modern day.

In fact, it almost turned into an impromptu David Haye and Tony Bellew pre-match fight when Charlton challenged hardened journalist and ex-international Eamon Dunphy’s line of questioning. That relationship turned increasingly sour as time went by.

This was the blueprint – or greenprint – of the Irish national team for the next decade.

Former players like Johnny Giles thought this indicated a lack of trust in the ability of players. Charlton saw it as pragmatic. His idea was to keep information and instruction simple.

This was the blueprint – or greenprint – of the Irish national team for the next decade.

Former players like Johnny Giles thought this indicated a lack of trust in the ability of players. Charlton saw it as pragmatic. His idea was to keep information and instruction simple.

After a 1-0 defeat to Wales in his first match in charge, Charlton got to work on qualifying for the 1988 European Championship in West Germany.

After a 1-0 defeat to Wales in his first match in charge, Charlton got to work on qualifying for the 1988 European Championship in West Germany.

While England staggered to defeat against the USSR and Holland, the Irish matched both teams stride for stride. Houghton described the 1-1 draw against the Soviets as “one of the best performances I’ve ever been involved in with Jack’s teams”.

While England staggered to defeat against the USSR and Holland, the Irish matched both teams stride for stride. Houghton described the 1-1 draw against the Soviets as “one of the best performances I’ve ever been involved in with Jack’s teams”.

A 1-1 draw with the Dutch meant both teams had identical records as all three of Holland, England and Ireland progressed, with the Irish benefiting from the drawing of lots to qualify as group runners-up

After three drab stalemates, the party only truly began in Genoa against Romania in the last 16 – after another goalless game, Bonner saved Romania’s fifth penalty, leaving David O’Leary to take the decisive kick.

RTE commentator George Hamilton uttered the most important seven words Irish fans remember: “A nation holds its breath… We’re there!”

How ironic that the hero was O’Leary, another more football-minded defender that was often overlooked by Charlton.

O’Leary recalled: “There were about 20,000 brilliant Irish supporters behind the goal. They were so still and the eruption of green afterwards when the ball hit the net was absolutely amazing. It’s a fantastic memory.”

A 1-1 draw with the Dutch meant both teams had identical records as all three of Holland, England and Ireland progressed, with the Irish benefiting from the drawing of lots to qualify as group runners-up

After three drab stalemates, the party only truly began in Genoa against Romania in the last 16 – after another goalless game, Bonner saved Romania’s fifth penalty, leaving David O’Leary to take the decisive kick.

RTE commentator George Hamilton uttered the most important seven words Irish fans remember: “A nation holds its breath… We’re there!”

How ironic that the hero was O’Leary, another more football-minded defender that was often overlooked by Charlton.

O’Leary recalled: “There were about 20,000 brilliant Irish supporters behind the goal. They were so still and the eruption of green afterwards when the ball hit the net was absolutely amazing. It’s a fantastic memory.”

Ireland’s propensity to draw a large proportion of games (30 out of 93 under Charlton) cost them dearly in the 1992 Euro qualifying group as only eight teams could qualify for Sweden.

They finished behind Graham Taylor’s stodgy England team, despite drawing home and away against them.

However, the Republic were reaching a new peak, with a young Roy Keane and Denis Irwin introduced to the team.

“The worst thing about missing out on Euro 92 was that Denmark won it. It should have been Ireland.” recalled a frustrated manager.

Ireland’s propensity to draw a large proportion of games (30 out of 93 under Charlton) cost them dearly in the 1992 Euro qualifying group as only eight teams could qualify for Sweden.

They finished behind Graham Taylor’s stodgy England team, despite drawing home and away against them.

However, the Republic were reaching a new peak, with a young Roy Keane and Denis Irwin introduced to the team.

“The worst thing about missing out on Euro 92 was that Denmark won it. It should have been Ireland.” recalled a frustrated manager.

In the USA, the party started early in New York as Italy were beaten in the Big Apple by a Houghton strike.

Patrick Barclay summed it up best in The Observer: “Ireland’s blanket defence rendered vain all the creative endeavours of Roberto Baggio, who adorned this marvellous occasion but was not allowed to influence it because for 90 mins Jack Charlton’s sweat-soaked soldiers stayed about as close as ranks can get.”

Unfortunately, Ireland’s performances tailed off dramatically for the remainder of the tournament.

Such draining tactics were hard to administer in the humidity of Orlando, and the manager was banned from the touchline for venting his fury at officials over the lack of water for his troops against Mexico.

After squeezing through the group following a goalless draw with Norway, the Green bus ran out of fuel against the Dutch in the last 16.

In the USA, the party started early in New York as Italy were beaten in the Big Apple by a Houghton strike.

Patrick Barclay summed it up best in The Observer: “Ireland’s blanket defence rendered vain all the creative endeavours of Roberto Baggio, who adorned this marvellous occasion but was not allowed to influence it because for 90 mins Jack Charlton’s sweat-soaked soldiers stayed about as close as ranks can get.”

Unfortunately, Ireland’s performances tailed off dramatically for the remainder of the tournament.

Such draining tactics were hard to administer in the humidity of Orlando, and the manager was banned from the touchline for venting his fury at officials over the lack of water for his troops against Mexico.

After squeezing through the group following a goalless draw with Norway, the Green bus ran out of fuel against the Dutch in the last 16.

It is sometimes opined in retrospect that the Republic could have done better with the quality of players at their disposal. They only won one of nine World Cup matches, scoring just four goals.

After USA’ 94, Dunphy said: “The minority who know their football well enough to distinguish between fact and fantasy have long since decided that even though the show is great, the football of the Charlton era has been, too often, lousy.”

But would liberation have taken away the organisational pragmatism that was central to the Green Wall being breached just 41 times in 93 games? After all, this was a team that also beat Brazil at home and Germany in Hannover.

Niall Quinn said: “We were happy as we were – beautiful, skilled losers.”

Big Jack made them coarse but clinical winners on the pitch and a lot happier off it.

It is sometimes opined in retrospect that the Republic could have done better with the quality of players at their disposal. They only won one of nine World Cup matches, scoring just four goals.

After USA’ 94, Dunphy said: “The minority who know their football well enough to distinguish between fact and fantasy have long since decided that even though the show is great, the football of the Charlton era has been, too often, lousy.”

But would liberation have taken away the organisational pragmatism that was central to the Green Wall being breached just 41 times in 93 games? After all, this was a team that also beat Brazil at home and Germany in Hannover.

Niall Quinn said: “We were happy as we were – beautiful, skilled losers.”

Big Jack made them coarse but clinical winners on the pitch and a lot happier off it.