46cm x 32cm Dublin

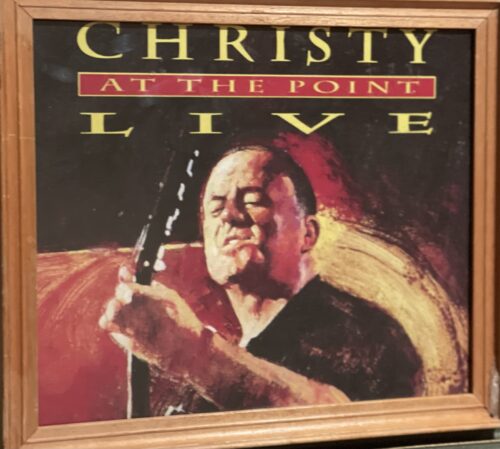

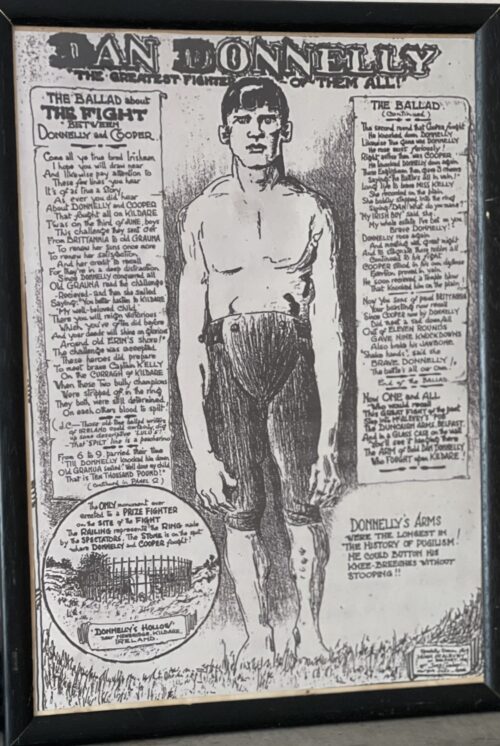

Daniel Donnelly (March 1788 – 18 February 1820) was a professional

boxing pioneer and the first Irish-born heavyweight champion. He was posthumously inducted into the

International Boxing Hall of Fame,

Pioneers Category in 2008.

Donnelly was born in the docks of

Dublin, Ireland in March 1788.

He came from a family of seventeen children.

Donnelly grew up in poverty; his father was a carpenter, but suffered from chest complaints and was frequently out of work. As soon as he was able, Donnelly also went to work as a carpenter.

On the streets of Dublin, Donnelly had a reputation of being a hard man to provoke, but was known to be "handy with his fists", and he became the district's new fighting hero.

There are a number of anecdotes about Donnelly's life in this period, including his rescue of a young woman being attacked by two sailors at the dockside, leading to his arm being badly mangled. He was taken to the premises of the prominent surgeon

Dr. Abraham Colles who saved Donnelly's arm from amputation, describing him as a "pocket Hercules".

Another tale concerns Donnelly's insistence of carrying the body of an old lady who had died of a highly contagious fever to a local graveyard, where he buried the body himself in a grave that had been "reserved for a person of distinction".

Early boxing career

Donnelly was nearly six feet (1.83 m) tall and weighed almost 14 stone (196 lbs, 89 kg).

He was described as "a courageous man".

As news of his fighting exploits with Dublin's feuding gangs spread swiftly.

He gained a reputation for keeping local criminals in check. One boxer, recognized as champion of the city, became jealous of Donnelly's reputation and took to following him around the local taverns demanding a fight. Eventually, Donnelly relented and the fight was staged on the banks of the

Grand Canal. The event aroused a great deal of interest in Dublin, and a good crowd turned up. Right up to the time they took sparring positions, Donnelly tried to talk his rival out of fighting, but his pleas fell on deaf ears. As the fight dragged on, Donnelly gradually overcame his rival, and in a furious attack in the 16th round, beat him to the ground. Donnelly was declared the new champion of the city.

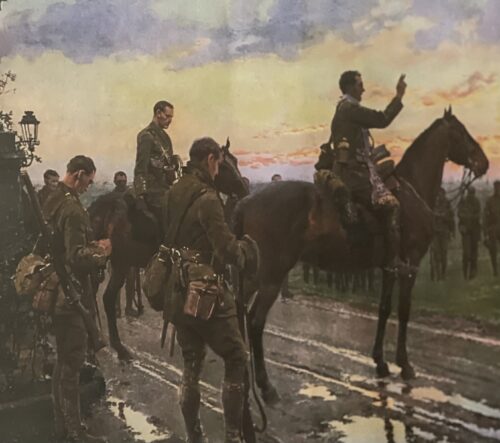

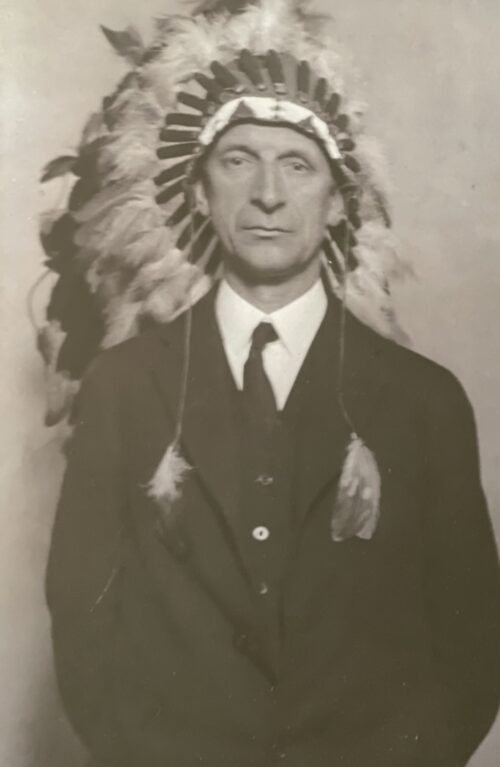

"Sporting" Captain William Kelly, the man credited with "discovering" Donnelly.

Around this time, an Irish aristocrat was sitting in an English tavern. Captain William Kelly listened as a pair of English prize-fighters mocked Ireland's reputation as a nation of courageous men.

Kelly considered this an affront to his native land and resolved to find a fighting Irishman to take up the challenge.

His search eventually took him to Dublin and to Dan Donnelly.

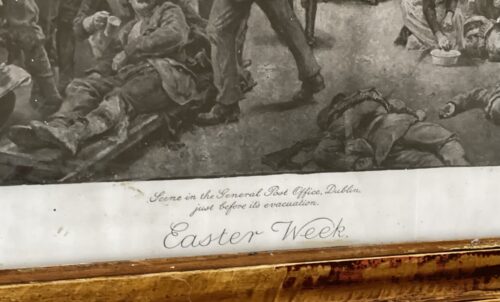

King of the Curragh

When prize fights were first introduced, it was the Fancy who tended to the boxers. The Fancy were aristocrats who followed the sport in the 18th and 19th centuries. They organized the training, the matches, and the finance. Donnelly's first big fight under the patronage of Captain Kelly, was staged at the

Curragh in

County Kildare on 14 September 1814.

The spot was known at the time as Belcher's Hollow, a natural amphitheatre that was regularly used for big prize fights. Donnelly's opponent was a prominent English fighter, Tom Hall, who was touring Ireland, giving sparring exhibitions and boxing instruction. By one o'clock when the bout was due to start, an estimated 20,000 people

packed onto the sides of the hollow, at the base of which a 22-foot (6.71 m) square had been roped off.

Jack Broughton's Rules, drawn up in 1743, lasted 110 years until replaced by the London Prize Ring Rules.

Boxing at that time was very different from the boxing of today. There were

few rules. There was no boxing organization to oversee the sport or lay down regulations or procedures. There was no formal end to the fights: they would go on until one fighter was unable to continue or would give up. A now obsolete practice was that of the seconds. The seconds would wait in the ring during the fight, and assist the boxer between rounds. There were no restrictions regarding fight tactics. For example, a fighter could hit his opponent's head off a corner post, or wrestle his opponent to the ground, or pull his hair, or wrap his arm around his neck in a choking motion and then hit him in the face with the other hand. The fights were very severe and often brutal, and they would continue until the end.

A round could last as long as six or seven minutes, or a little as 30 seconds. The round would end when one person was on the ground. He would then have 30 seconds to get up and continue the fight.

For a few rounds, Hall was showing his skill was paramount. He scored first blood, which was an important occasion in bare-fist boxing; there were bets made on who would draw first blood. But as the rounds went on, Donnelly's strength began to tell. Hall would slip down onto his knee, without being in any danger. This was a tactic, because once he went down the round was over, he got a 30-second rest, and came back refreshed. He was doing this just a bit too often for Donnelly's liking, and at one stage, Donnelly was just about to lash out when he was down, and his second shouted out an admonishment that Dan would lose the fight if he did so. Eventually he did lose his temper, and as Hall slipped down yet again, Donnelly lashed out and hit him on the ear; the blood flowed. That was the end of the round. Hall refused to continue, saying he had been fouled, that Donnelly should be disqualified. Donnelly fans voiced that no, Dan had definitely won, Hall didn't want to fight on, Donnelly was the champion. The fight ended in some controversy, but to the Irish, he was the conquering hero.

Belcher's Hollow was rechristened Donnelly's Hollow and Dan Donnelly was now acclaimed as Ireland's Champion.

For a short while, at least, the country celebrated its new hero. The Irish saw sporting heroes like Dan Donnelly as the symbolic winner of the bigger fight. While Ireland was left without its own government, England was becoming increasingly more powerful. Whenever Dan's right hand bloodied an English nose, it was hailed as a strike, however small, against the oppressors.

Cooper's challenge

It was the summer of 1815, and while Ireland was at its weakest, England had never seemed stronger.

Wellington had beaten

Napoleon at

Waterloo and

Britanniacertainly ruled the waves. In the minds of the populace, Dan Donnelly epitomized the national struggle in an Ireland governed by mad old

George III, championing their seemingly hopeless cause against the intransigent representatives of

the Crown.

In

Irish folk tradition, the hero took center stage.

That goes back to the storytelling tradition which still exists today. The hero is revered; he's someone who is willing to stand up and fight for himself and his people. Dan was synonymous with Ireland as he was a patriot. He lived and fought in the period after the 1798 Rebellion and the Act of Union, and during the

Catholic Emancipation movement. Spirits and morale were good in Ireland at that time. As a patriotic man himself, the timing couldn't be better for Donnelly.

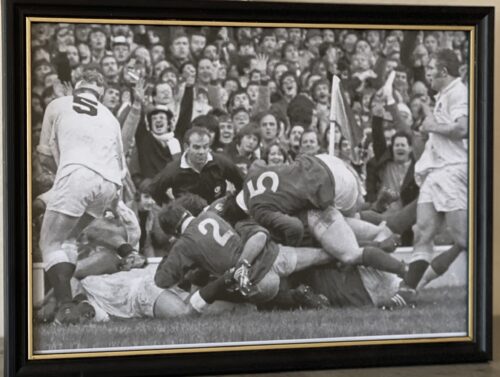

The political climate between Ireland and Britain is better and more peaceful today than it has been in a very long time, but if a rugby or soccer game is held between the two countries, there is a certain amount of tension or

jingoism.

Dan Donnelly and his boxing matches embodied this mentality in the early 19th century. It's symbolic of how the Irish and the English fought their political battles on the football pitch and in the boxing ring.

Donnelly was a national hero, but he was also broke.

He drank away the purse from beating Tom Hall, but the chance of another big payday eventually presented itself. He was approached by George Cooper and

Tom Molyneux, two leading prize-fighters who were touring Ireland on an exhibition tour to teach the art of boxing.

George Cooper, a first-rate ringman, and the opponent in Donnelly's most celebrated victory.

These two came to Dublin, heard of Donnelly, and invited him to meet them in a local pub. They prevailed upon him to fight Molyneux originally, and he said no. He had no desire to fight a conquered man, because Molyneux had just been beaten by the other man of the company, George Cooper. Molyneux was hurt by this curt refusal, but he was calmed down by his companion. Arrangements were made for the fight with Cooper.

The bout was set for 13 November 1815.

Once again, it was to be staged at Donnelly's Hollow on the Curragh in County Kildare.

News of Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo was resounding around Europe. George Cooper was a hotter favorite than the Iron Duke had been in his bout with the Little Corporal. Cooper was a bargeman with a fearful reputation.

He was of gypsy blood

and he was 10/1 on to batter Dan Donnelly.

From early morning, crews began to converge on Donnelly's Hollow.

They came from far and wide, using every horse-drawn contraption they could find, or on horseback. If they couldn't do so, they gladly walked the distance. There were 20,000 people packed in there on that day. Excitement was intense.

Bets were made back then as is still customary to this day.

Bets were made on the results of the fight, on who'd draw the first blood, or on who would score the first knockdown. There were rules, but they were designed to accommodate gambling, the public, and those who organized the fight. The boxers themselves were of no consequence.

It was a fight that went one way then the other for a round. Again, Donnelly's strength would always tell in a bare-knuckle fight to the finish.

In one round, Cooper used the cross-buttock tactic with Donnelly and severely winded him.

The cross-buttock was more a wrestling maneuver than a boxing one, but it was legitimate under the rules of the time. A competitor gets, more or less, in front of his opponent, and throws his adversary over his hip, causing him to land with great force on the ground.

If one popular story is to be believed, Donnelly, who was being badly beaten in the fifth round, was saved by the magical properties of a lump of sugar cane slipped to him by Captain Kelly's sister. She had been pleading with Dan to win, telling him she had bet her entire estate on the outcome. When Donnelly failed to respond, she slipped him a piece of the sugar cane, while urging him, "Now my charmer, give him a warmer!"

The Irish champion was rejuvenated and the course of the fight changed.

In the seventh round, he sent Cooper flat on his back on the turf and jumped on top of him, winding Cooper so badly he could hardly rise.

He did rise for the next round, but in the eleventh, Donnelly finished him off with a tremendous right hand that smashed Cooper's jaw.

The sound of the cheering was likened to the sound of artillery going off.

The cheers could be heard in villages for miles around.

Donnelly was the conquering hero.

As Donnelly proudly strode up the hill towards his carriage, fanatical followers dug out imprints left by his feet.

Leading from the monument which commemorates the scene of his greatest victory, "The Steps to Strength and Fame" are still to be seen in Donnelly's Hollow. Donnelly politely declined all invitations to celebrate his triumph in the taverns of County Kildare. He had promised his friends and family he would return to Dublin immediately after the fight.

Newspapers in the 18th century had many references to boxing. However, this was bare-knuckle fighting, fighting that was severe and sometimes brutal. That type of boxing was at its most popular during Dan's time. Boxing champions in those days became well-renowned. He was aware that political conflict was very much to the fore then. He accepted that he was representing the Irish people in this area in which he was active. He was a patriot, who, if needed, would stand up for his beliefs.

Monument at Donnelly's Hollow on the Curragh in County Kildare"

Footsteps at Donnelly's Hollow on the Curragh in County Kildare"

Later life

Donnelly became a publican, hoping his notoriety would entice extra customers eager to hear stirring tales of his prize-ring. He had a

reputation for being a

gambler, a

womanizer and a

drunkard. Donnelly was the

proprietor of a succession of four Dublin

pubs, all of them unprofitable. Fallon's Capstan Bar is the only one still in existence.

In his third and final fight on 21 July 1819, he defeated Tom Oliver in 34 rounds on English turf, at

Crawley Down in

Sussex. A full fight report was filed by the foremost prizefighting chronicler of the period,

Pierce Egan. Egan irately described the reception accorded to Donnelly during a benefit night (6 April 1819) as 'rather foul': 'It was very unlike the usual generosity of John Bull towards a stranger – It was not national – but savoured something like prejudice' (

Boxiana, vol. III).

This animosity was borne predominantly from concern over the Irishman's fighting prowess, and Egan underscored the combination of resentment and overwhelming interest when reporting Donnelly's fight with Oliver: 'The English amateurs viewed him as a powerful opponent [and...] jealous for the reputation of the "Prize Ring", clenched their fists in opposition, whenever his growing fame was chaunted' (

Boxiana, vol. III)

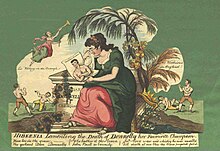

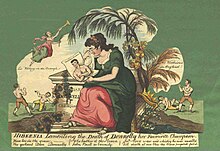

Hibernia lamenting the Death of Donnelly, her favourite champion.

He died at Donnelly's Public House, the last tavern he owned, on 18 February 1820 at the age of 31. An

oval wall plaquecommemorates the site of his

death. A squat, weather-beaten,

gray obelisk surrounded by a short

iron fence marks the exact site of the Cooper bout. The inscription on the

monument: DAN DONNELLY BEAT COOPER ON THIS SPOT 13 December 1815. The date inscribed was inaccurate, as the bout actually took place one month earlier, on 13 November 1815, as reported in the Freeman's Journal the following day.

Donnelly's arm

Donnelly was laid to rest, albeit briefly, at

Bully's Acre, one of the city's oldest cemeteries.

After just a few nights,

grave robbers put Donnelly's body in a sack and delivered him to an eminent surgeon who paid good money for cadavers for study.

They may even have been working to order.

Donnelly's admirers tracked the body to the home of a surgeon by the name of Hall and threatened him with death.

There was a quick negotiation and he agreed to give the body back as long as he could keep the right arm, the one that slew the English champions, for medical observation.

The arm was preserved in red lead paint,

and traveled to a

medical college in Scotland where it was used by medical students for a number of years to study how all the bones worked together.

From an

Edinburgh classroom, the arm became an exhibit in a

Victorian travelling circus,

and it journeyed around Britain many times. In the early 20th century, it finally came back to Ireland. In 1904, a

Belfast bookmaker, Hugh "Texas" McAlevey, acquired the arm and displayed it in his pub.

The publican got tired of it and thought the grisly-looking sight might be frightening off customers, so he stuck it up in an attic.

A betting parlor employee remembers as a teenager being told not to go up in the attic—that Donnelly's ghost was up there.

Donnelly's arm made it back to

Kilcullen in the 1950s.

Publican Jim Byrne came up with the idea of recreating Donnelly's fight with George Cooper in the Curragh.

The fight was promoted by bringing Donnelly's arm back to where it defeated the English opponent.

The pageant brought the historic contest alive again, rekindling the Dan Donnelly fire.

It was

An Tóstal, an Irish festival started at that time nationwide in an effort to promote tourism.

Each region was encouraged to have some sort of festival to attract visitors. This was the genesis of the Dan Donnelly pageant.

Kevin McCourt, an army officer, was picked to play George Cooper, the English champion; Jim Berney was chosen to portray Dan Donnelly, the Irish champion. George Cooper and Dan Donnelly, as played by McCourt and Berney, had a group of supporters as well, dressed up and cheering, carrying them down into the arena.

Two "supporters" performed getting involved in a ruckus. Local sporting clubs and townspeople comprised the spectators.

"The longest arms in the history of pugilism."

Donnelly's arm found a new home in Jim Byrne's pub, "The Hideout."

It became a popular attraction in

Kilcullen.

It was on display there for 43 years until Jim Byrne died and the pub passed to his son, Desmond,

who was unaware of the arms value, and in 1997 he eventually sold the pub.

The arm sat in his and Josephine's basement piled under junk for almost a decade until an American

relative, Thomas Donnelly, began a national search for the arm. After several radio interviews and articles, the nations intrigue began to grow again on the whereabouts of the arm.

Des died in 2005. After the media search gained traction, Josephine revealed that they kept the arm during the sale and it was disrespectfully laying in their basement.

Josephine wouldn't let the human limb that was almost 200 years old go into a cargo hold for transportation to America. One of Des's bandmates had been Henry Donohoe, then the chief pilot for

Aer Lingus.

She called him and asked how to get the arm to the States. He told her that he would take it in the cockpit with himself.

Josephine sat in first class. A special box was made for the arm, crating around it to prevent it from getting banged around. It fit into the cockpit with two inches to spare.

As the centerpiece of the Fighting Irishmen Exhibit, Donnelly's arm went on display at the Irish Arts Center in New York City, in the autumn of 2006.

The show traveled across the city to the South Street Seaport Museum in 2007.

Its next appearance was at

Boston College's John J. Burns Library in 2008.

The arm returned to Ireland in 2009 when the show arrived at the

Ulster American Folk Park in

Omagh.

2010 was a homecoming when the exhibition appeared at the

Gaelic Athletic Association museum at

Croke Park in Dublin.

Legends

Almost two

centuries after his death. Donnelly remains the subject of

urban legend. One contends that he had the longest

arms in boxing history, with the ability to touch his

knees without bending down. Another claims that he was knighted by the

Prince Regent. His arms were actually of normal length for a man of his size. No known documentation exists to support the latter.