The 1938 All-Ireland Football Final Replay on October 23rd, 1938 ended in the most bizarre fashion imaginable when with 2 minutes left to play, Galway supporters, mistakenly believing the referee had blown for full-time, invaded the pitch, causing a 20 minute delay before the final minutes could be played out.

Even more dramatic was the fact that by the time the pitch was cleared, most of the Kerry players seemed to have disappeared.

The confusion all began with a free awarded to Kerry by referee Peter Waters of Kildare with Galway leading the defending champions, by 2-4 to 0-6.

The referee placed the ball and blew his whistle for the kick to be taken while running towards the Galway goals. He looked round just as Sean Brosnan was taking the kick and seeing a Galway player too close he blew for the kick to be retaken.

Thinking that he had blown for full-time the jubilant Galway supporters invaded the pitch.

It took all of twenty minutes to clear the pitch but only then did the real problems come to light. Jerry O’Leary Chairman of the Kerry Selection Committee outlined their dilemma.

Somehow or other Kerry managed to re-field even if the team which played out the remaining minutes bore little resemblance to the starting fifteen.

More remarkable again was the fact that Kerry went on to add another point to their total before the referee finally blew for full-time with Galway winners by 2-4 to 0-7.

It was generally agreed that the confusion was of the crowd’s and not the referee’s making but questions remained about the total number of players Kerry had been permitted to use in those final few minutes.

The National and Provincial papers and indeed all available Records to this day list only those 16 Kerry players who were involved prior to the 20 minute interruption but now (80 years on) for the first time all the players who played for Kerry in that October 23rd, 1938 All-Ireland Final Replay can be given their rightful place in the Record Books.

KERRY’s 24:

- Dan O’Keeffe (Tralee O’Rahilly’s)

- Bill Kinnerk (Tralee, Boherbee John Mitchel’s)(Captain)

- Paddy ‘Bawn’ Brosnan (Dingle)

- Bill Myers (Killarney)

- Bill Dillon Dingle)

- Bill Casey (Dingle)

- Tom ‘Gega’ O’Connor (Dingle)

- Sean Brosnan (Dingle)

- Johnny Walsh (Ballylongford, North Kerry)

- Paddy Kennedy (Tralee O’Rahilly’s)(Annascaul native)

- Charlie O’Sullivan (Tralee O’Rahilly’s)(Camp native)

- Tony McAuliffe (Listowel, North Kerry)

- Martin Regan (Tralee Rock Street Austin Stacks)

- Michael ‘Miko’ Doyle ((Tralee Rock Street Austin Stacks)

- Timmy O’Leary (Killarney).

- J.J. ‘Purty’ Landers (Tralee Rock Street Austin Stacks)(brother of Tim and Bill)(replaced Johnny Walsh – injured hip and dislocated collarbone)

- Joe Keohane (Geraldines, Dublin)(former Tralee Boherbee John Mitchel’s player)

- Michael ‘Murt’ Kelly (Geraldine’s, Dublin)(formerly Tralee O’Rahilly’s)

- J.Sheehy (Tralee Boherbee John Mitchel’s)

- Eddie Walsh (Knocknagoshel, North Kerry)

- Ger Teahan (Laune Rangers, Killorglin)

- Bob Murphy (Newtown, North Kerry)

- Con Gainey (Tralee Boherbee John Mitchel’s)(Castleisland native)

- M. Raymond (Tralee O’Rahilly’s)

So in total and in contravention of the Rules Kerry used 24 players including 9 substitutes. Galway in contrast used a mere 17 players including 2 substitutes.

GALWAY’S 17:

- Jimmy McGauran (University College Galway)(Roscommon native)

- Mick Raftery (University College Galway)(Mayo native)

- Mick Connaire (Beann Éadair, Dublin)(Ballinasloe native)

- Dinny Sullivan (Oughterard)

- Frank Cunniffe (Beann Éadair, Dublin)(Ballinasloe native)

- Bobby Beggs (Wolfe Tones, Galway City)(Dublin native)(former Skerries Harps player)

- Charlie Connolly (Ballinasloe Mental Hospital)

- John ‘Tull’ Dunne (Ballinasloe St. Grellan’s)(Captain)

- John Burke (Remore)(Clare native)

- Jackie Flavin (Wolfe Tones, Galway City)(Kerry native – Newtownsandes)(won 1937 All-Ireland with Kerry)

- Ralph Griffin (Ballinasloe St. Grellan’s)

- Mick Higgins (Wolfe Tones, Galway City)

- Ned Mulholland (Wolfe Tones, Galway City)(Westmeath native)

- Martin Kelly (Ardagh, Limerick)(Ahascragh native)

- Brendan Nestor (Geraldines, Dublin)(Dunmore native)

- Mick Ryder (Tuam Stars)

- Pat McDonagh

It was almost as if Galway had won the All-Ireland twice in one day beating two different Kerry teams in the process.

That night, in front of a 1,500 crowd, at a Gaelic League organised Siamsa Mór in the Mansion House in Dawson Street, Art McCann presented the Galway team with their winners’ medals.

The Kerry players meanwhile joined 300 of their suppoeters at a Ceilidhe hosted by the Kerrymen’s Social Club in Rathmines Town Hall.

The National Newspapers may not always have reported the facts to Galway’s satisfaction but there can be no questioning the support of Galway County Council.

Needless to say the Galway players received an unprecedented welcome on their return to Galway having first been feted along the way in Mullingar, Streamstown, Moate and Athlone.

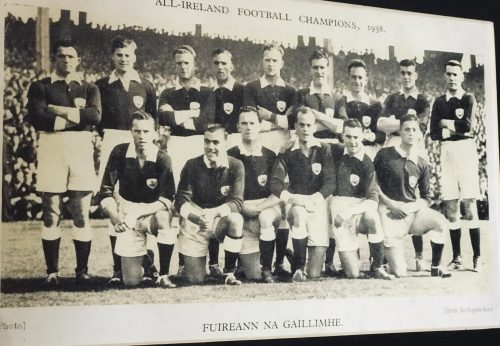

GALWAY – 1938 ALL-IRELAND SENIOR FOOTBALL CHAMPIONS

Back (L-R) Bobby Beggs, Ralph Griffin, John Burke, Jimmy McGauran, Charlie Connolly, Brendan Nestor, Dinny Sullivan, Mick Connaire, Martin Kelly. Front (L-R) Frank Cunniffe, Jackie Flavin, Mick Higgins, John ‘Tull’ Dunne (Capt), Ned Mulholland, Mick Raftery.

Substitutes: (not in photograph) Mick Ryder and Pat McDonagh.

TIME ADDED ON:

Not far behind the controversy surrounding the last few minutes of 1938 All-Ireland Football Final Replay was the controversy surrounding the last few seconds of the drawn match played a month earlier.

The sides were level, Kerry 2-06 Galway 3-03, when Kerry’s J.J. Landers sent the ball between the Galway uprights for what looked like the winning point. However the thousands of celebrating Kerry supporters making for the Croke Park exits were soon stopped in their tracks.

It was cruel luck on Kerry and while there were many who criticised the referee, Tom Culhane from Glin, County Limerick, for blowing the final whistle while John Joe Landers was it the act of shooting, Kerry’s County Board Chairman Denis J. Bailey wasn’t among them.

At the next Central Council meeting, in a remarkably generous response to the Referee’s Report being read he stated that ‘they in Kerry were quite satisfied with the result’ and ‘They wished to pay a tribute to Galway for their sporting spirit and also to the referee who, in their opinion, carried out his duties very well.’

The Central Council then awarded the two counties £300 each towards the costs of the two-week Collective Training Camps both counties had planned in the lead up to the Replay on October 23rd. Munster Council granted Kerry (pictured here in Collective Training) an additional £100.

Prior to that Central Council meeting, General Secretary, Pádraig Ó’Caoimh, received a telephone call from the New York GAA suggesting the replay take place in New York but the request (which was successfully repeated nine years later in 1947) was on this occasion turned down.

However doubts about the Replay even going ahead were immediately raised.

Satisfactory transport arrangements were eventually agreed and the match went ahead although the Kerry supporters who left Tralee on the so-called ‘ghost’ train at 1am on the morning of the October 23rd may still have felt hard done by.

In the lead-up to the game the Galway selectors expressed their delight at the success of their forwards short hand-passing game against the Kerry backs in the drawn match although there were some worries that not all their players had been able to attend the first week of Collective Training and of course there was Kerry’s Replay record to be considered.

Kerry had previously played in 4 All-Ireland Replays and won them all, a great source of encouragement to the Kerry supporters.

However amid some reports of disharmony within the Kerry camp, following a ‘trial match’ on the Sunday before the Replay, the Kerry selection Committee dropped a real bombshell.

Joe Keohane (Dublin Geraldines) who had been Kerry’s regular full-back for the previous two years and was one of the stars of their 1937 All-Ireland win over Cavan was replaced by young Paddy ‘Bawn’ Brosnan a member of the 1938 Kerry Junior team.

A back injury to Kerry’s best forward, J.J. Landers made him an extreme doubt for the Replay with Martin Regan on stand-by to take his place if required which is exactly what happened before that fateful free-kick, that infamous 20 minute delay and Kerry’s unprecedented use of 24 players.

Most definitely an All-Ireland Final and Final Replay never to be forgotten.

The Galway and Kerry players parade in front of the newly opened (1938) Cusack Stand

Tom Moloughney, Jimmy Doyle, and Kieran Carey relax in the dressing room after Tipperary’s victory over Dublin in the 1961 All-Ireland final, a success that was to be repeated the following year. Picture from ‘The GAA — A People’s History’

Tom Moloughney, Jimmy Doyle, and Kieran Carey relax in the dressing room after Tipperary’s victory over Dublin in the 1961 All-Ireland final, a success that was to be repeated the following year. Picture from ‘The GAA — A People’s History’

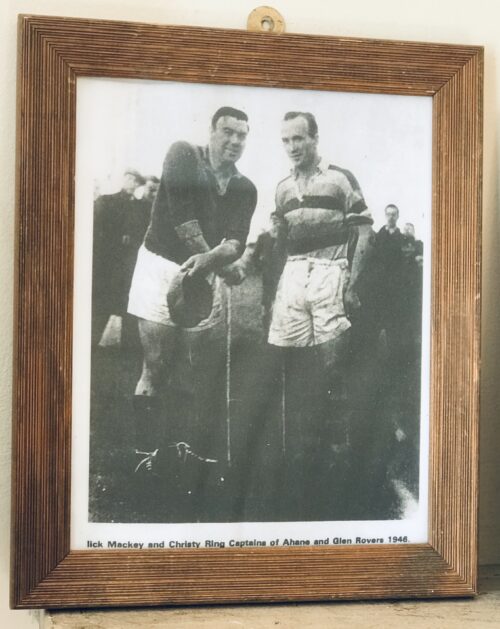

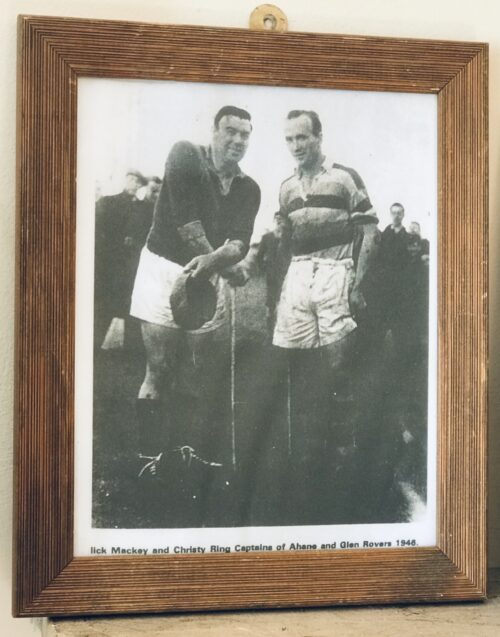

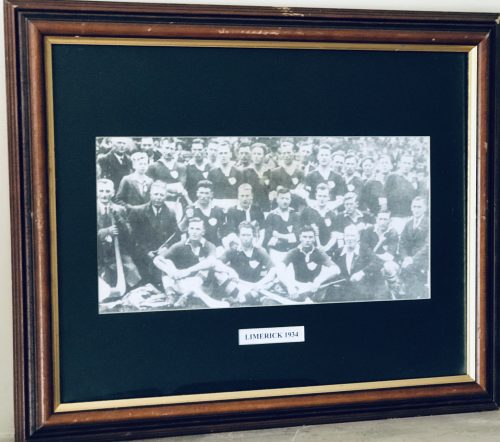

Limerick 5-2 Dublin 2-6

D Clohessy 4-0, M Mackey 1-1, J O’Connell 0-1

Limerick 5-2 Dublin 2-6

D Clohessy 4-0, M Mackey 1-1, J O’Connell 0-1