-

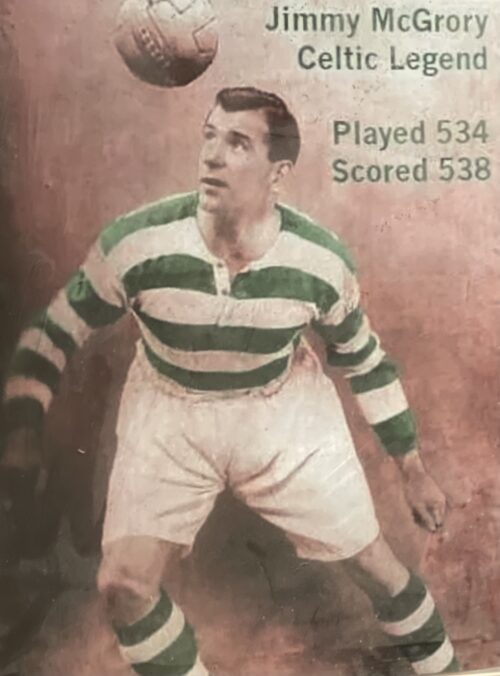

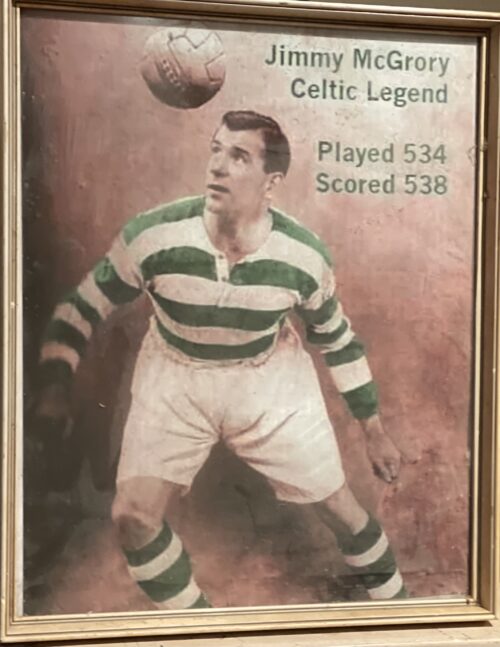

Framed moment of Glasgow Celtic Great-Jimmy McGrory. Dunfanaghy Co Donegal 40cm x 33cm James Edward McGrory (26 April 1904 – 20 October 1982) was a Scottish International football player, who played for Celtic and Clydebank as a forward, and then went on to manage Kilmarnock, before returning to Celtic as manager after the end of the Second World War. He is the all-time leading goalscorer in top-flight British football with a total of 550 goals in competitive first-team games at club and international level. McGrory is a legendary figure within Celtic's history; he is their top scorer of all time with 522 goals, and holds their record for the most goals in a season, with 57 League and Scottish Cup goals from 39 games in season 1926–27. He has also notched up a British top-flight record of 55 hat-tricks, 48 coming in League games and 7 from Scottish Cup ties. It could be argued he in fact scored 56, as he hit 8 goals in a Scottish League game against Dunfermline in 1928, also a British top-flight record. He was at Celtic for 15 years between 1922 and 1937, although he did spend the majority of the 1923–24 season on loan at fellow 1st Division side Clydebank. After a spell managing Kilmarnock from December 1937 to July 1945, he became Celtic manager, where he remained for just under 20 years, until March 1965 when he was succeeded by Jock Stein. Even although he was only 5 ft 6ins, he was renowned for his prowess and ability from headers. His trademark was an almost horizontal, bullet header, which he performed and scored regularly from and which earned him his nicknames, of the "Human Torpedo" and the "Mermaid".No honours were achieved either in 1929–30, although McGrory continued to score regularly, netting 36 goals in 29 League and Scottish Cup games. Injuries were by now starting to take their toll on McGrory, who was always a regular target for some brutal 'defending'. He missed the first six games of season 1930–31 due to such an injury.While the Leaguecampaign was to ultimately prove disappointing, the team had shown promise and improved on the previous seasons finish of fourth place, running eventual winners Rangers close and finishing in second place only two points behind them. Celtic scored 101 goals in the process,with McGrory helping himself to a very credible 36 of them in only 29 games. The 1930–31 Scottish Cup was to prove more fruitful all round, where he ended up with a winners medal and 8 goals from 6 games. In the Cup Final on 11 April 1931, he scored the opening goal in a 2–2 draw against Motherwell in front of crowd of 104,863 at Hampden Park, Glasgow. The replay took place on 15 April 1931, which Celtic won 4–2 thanks to two goals each from McGrory and Bertie Thomson. Celtic found themselves way off the pace again in the 1931–32 Scottish Division One, finishing in third place, 18 points behind champions Motherwell.A huge factor in Celtic's indifferent season was the death of their goalkeeper John Thomson on 5 September 1931 at Ibrox Park. Rangers forward Sam English collided with Thomson and his knee struck the Celtic goalkeepers temple, fracturing his skull. Thomson was rushed to the Victoria Infirmary in Glasgow, but died later that evening. The effect on the team was evident in their general performance from that point onwards. McGrory, on top of losing a teammate and friend, was succumbing to more serious injuries and missed large chunks of the season, only playing in 22 of the 38 League games. He and Celtic fared little better in the Scottish Cup, again losing out to Motherwell at the first round of entry, in round three. The injuries put paid to his usual high goal tally, and he suffered his lowest seasonal total since his first full season in 1924–25 season, with 28 goals in 23 League and Scottish Cup games. On 14 March 1936, McGrory achieved the fastest hat-trick in Scottish League history, scoring three goals in less than 3 minutes, during a 5–0 win over Motherwell.McGrory was allowed to leave Celtic in December 1937 to become the manager of Kilmarnock, on the condition that he retired from playing.

Framed moment of Glasgow Celtic Great-Jimmy McGrory. Dunfanaghy Co Donegal 40cm x 33cm James Edward McGrory (26 April 1904 – 20 October 1982) was a Scottish International football player, who played for Celtic and Clydebank as a forward, and then went on to manage Kilmarnock, before returning to Celtic as manager after the end of the Second World War. He is the all-time leading goalscorer in top-flight British football with a total of 550 goals in competitive first-team games at club and international level. McGrory is a legendary figure within Celtic's history; he is their top scorer of all time with 522 goals, and holds their record for the most goals in a season, with 57 League and Scottish Cup goals from 39 games in season 1926–27. He has also notched up a British top-flight record of 55 hat-tricks, 48 coming in League games and 7 from Scottish Cup ties. It could be argued he in fact scored 56, as he hit 8 goals in a Scottish League game against Dunfermline in 1928, also a British top-flight record. He was at Celtic for 15 years between 1922 and 1937, although he did spend the majority of the 1923–24 season on loan at fellow 1st Division side Clydebank. After a spell managing Kilmarnock from December 1937 to July 1945, he became Celtic manager, where he remained for just under 20 years, until March 1965 when he was succeeded by Jock Stein. Even although he was only 5 ft 6ins, he was renowned for his prowess and ability from headers. His trademark was an almost horizontal, bullet header, which he performed and scored regularly from and which earned him his nicknames, of the "Human Torpedo" and the "Mermaid".No honours were achieved either in 1929–30, although McGrory continued to score regularly, netting 36 goals in 29 League and Scottish Cup games. Injuries were by now starting to take their toll on McGrory, who was always a regular target for some brutal 'defending'. He missed the first six games of season 1930–31 due to such an injury.While the Leaguecampaign was to ultimately prove disappointing, the team had shown promise and improved on the previous seasons finish of fourth place, running eventual winners Rangers close and finishing in second place only two points behind them. Celtic scored 101 goals in the process,with McGrory helping himself to a very credible 36 of them in only 29 games. The 1930–31 Scottish Cup was to prove more fruitful all round, where he ended up with a winners medal and 8 goals from 6 games. In the Cup Final on 11 April 1931, he scored the opening goal in a 2–2 draw against Motherwell in front of crowd of 104,863 at Hampden Park, Glasgow. The replay took place on 15 April 1931, which Celtic won 4–2 thanks to two goals each from McGrory and Bertie Thomson. Celtic found themselves way off the pace again in the 1931–32 Scottish Division One, finishing in third place, 18 points behind champions Motherwell.A huge factor in Celtic's indifferent season was the death of their goalkeeper John Thomson on 5 September 1931 at Ibrox Park. Rangers forward Sam English collided with Thomson and his knee struck the Celtic goalkeepers temple, fracturing his skull. Thomson was rushed to the Victoria Infirmary in Glasgow, but died later that evening. The effect on the team was evident in their general performance from that point onwards. McGrory, on top of losing a teammate and friend, was succumbing to more serious injuries and missed large chunks of the season, only playing in 22 of the 38 League games. He and Celtic fared little better in the Scottish Cup, again losing out to Motherwell at the first round of entry, in round three. The injuries put paid to his usual high goal tally, and he suffered his lowest seasonal total since his first full season in 1924–25 season, with 28 goals in 23 League and Scottish Cup games. On 14 March 1936, McGrory achieved the fastest hat-trick in Scottish League history, scoring three goals in less than 3 minutes, during a 5–0 win over Motherwell.McGrory was allowed to leave Celtic in December 1937 to become the manager of Kilmarnock, on the condition that he retired from playing. -

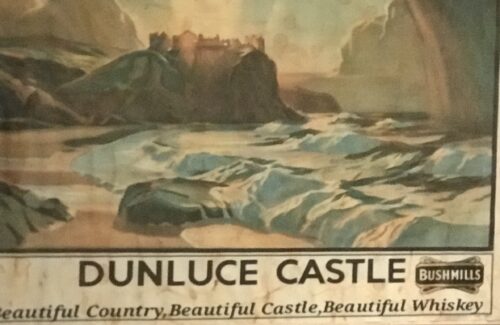

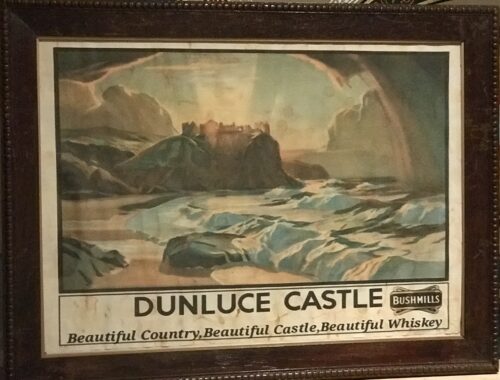

Classy advert depicting the magnificence of Dunluce Castle ,just down the road from the famed Bushmills Distillery. Portrush Co Antrim 52cm x 72cm In the 13th century, Richard Óg de Burgh, 2nd Earl of Ulster, built the first castle at Dunluce. It is first documented in the hands of the McQuillan family in 1513. The earliest features of the castle are two large drum towers about 9 metres (30 ft) in diameter on the eastern side, both relics of a stronghold built here by the McQuillans after they became lords of the Route. The McQuillans were the Lords of Route from the late 13th century until they were displaced by the MacDonnell after losing two major battles against them during the mid- and late-16th century. Later Dunluce Castle became the home of the chief of the Clan MacDonnell of Antrim and the Clan MacDonald of Dunnyveg from Scotland. Chief John Mor MacDonald was the second son of Good John of Islay, Lord of the Isles, 6th chief of Clan Donald in Scotland. John Mor MacDonald l was born through John of Islay's second marriage to Princess Margaret Stewart, daughter of King Robert II of Scotland. In 1584, on the death of James MacDonald the 6th chief of the Clan MacDonald of Antrim and Dunnyveg, the Antrim Glens were seized by Sorley Boy MacDonnell, one of his younger brothers. Sorley Boy took the castle, keeping it for himself and improving it in the Scottish style. Sorley Boy swore allegiance to Queen Elizabeth I and his son Randal was made 1st Earl of Antrim by King James I. Four years later, the Girona, a galleass from the Spanish Armada, was wrecked in a storm on the rocks nearby. The cannons from the ship were installed in the gatehouses and the rest of the cargo sold, the funds being used to restore the castle. MacDonnell's granddaughter Rose was born in the castle in 1613. A local legend states that at one point, part of the kitchen next to the cliff face collapsed into the sea, after which the wife of the owner refused to live in the castle any longer. According to a legend, when the kitchen fell into the sea, only a kitchen boy survived, as he was sitting in the corner of the kitchen which did not collapse. However, the kitchen is still intact and next to the manor house. You can still see the oven, fireplace and entry ways into it. It wasn't until some time in the 18th century that the north wall of the residence building collapsed into the sea. The east, west and south walls still stand. Dunluce Castle served as the seat of the Earl of Antrim until the impoverishment of the MacDonnells in 1690, following the Battle of the Boyne. Since that time, the castle has deteriorated and parts were scavenged to serve as materials for nearby buildings.

Classy advert depicting the magnificence of Dunluce Castle ,just down the road from the famed Bushmills Distillery. Portrush Co Antrim 52cm x 72cm In the 13th century, Richard Óg de Burgh, 2nd Earl of Ulster, built the first castle at Dunluce. It is first documented in the hands of the McQuillan family in 1513. The earliest features of the castle are two large drum towers about 9 metres (30 ft) in diameter on the eastern side, both relics of a stronghold built here by the McQuillans after they became lords of the Route. The McQuillans were the Lords of Route from the late 13th century until they were displaced by the MacDonnell after losing two major battles against them during the mid- and late-16th century. Later Dunluce Castle became the home of the chief of the Clan MacDonnell of Antrim and the Clan MacDonald of Dunnyveg from Scotland. Chief John Mor MacDonald was the second son of Good John of Islay, Lord of the Isles, 6th chief of Clan Donald in Scotland. John Mor MacDonald l was born through John of Islay's second marriage to Princess Margaret Stewart, daughter of King Robert II of Scotland. In 1584, on the death of James MacDonald the 6th chief of the Clan MacDonald of Antrim and Dunnyveg, the Antrim Glens were seized by Sorley Boy MacDonnell, one of his younger brothers. Sorley Boy took the castle, keeping it for himself and improving it in the Scottish style. Sorley Boy swore allegiance to Queen Elizabeth I and his son Randal was made 1st Earl of Antrim by King James I. Four years later, the Girona, a galleass from the Spanish Armada, was wrecked in a storm on the rocks nearby. The cannons from the ship were installed in the gatehouses and the rest of the cargo sold, the funds being used to restore the castle. MacDonnell's granddaughter Rose was born in the castle in 1613. A local legend states that at one point, part of the kitchen next to the cliff face collapsed into the sea, after which the wife of the owner refused to live in the castle any longer. According to a legend, when the kitchen fell into the sea, only a kitchen boy survived, as he was sitting in the corner of the kitchen which did not collapse. However, the kitchen is still intact and next to the manor house. You can still see the oven, fireplace and entry ways into it. It wasn't until some time in the 18th century that the north wall of the residence building collapsed into the sea. The east, west and south walls still stand. Dunluce Castle served as the seat of the Earl of Antrim until the impoverishment of the MacDonnells in 1690, following the Battle of the Boyne. Since that time, the castle has deteriorated and parts were scavenged to serve as materials for nearby buildings.Dunluce town

In 2011, major archaeological excavations found significant remains of the "lost town of Dunluce", which was razed to the ground in the Irish uprising of 1641. Lying adjacent to Dunluce Castle, the town was built around 1608 by Randall MacDonnell, the first Earl of Antrim, and pre-dates the official Plantation of Ulster.It may have contained the most revolutionary housing in Europe when it was built in the early 17th century, including indoor toilets which had only started to be introduced around Europe at the time, and a complex street network based on a grid system. 95% of the town is still to be discovered.Cultural references

- The castle inspired the orchestral tone poem Dunluce (1921) by Irish composer Norman Hay.

- Dunluce Castle is thought to be the inspiration for Cair Paravel in C. S. Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia (1950–54).

- Ron Moody menaced Jack Wild and Helen Raye at Dunluce Castle in Flight of the Doves, a 1971 film.

- In 1973 the castle appeared on the inner gatefold of the multi-million selling Led Zeppelin album Houses of the Holy.

- On the 1984 Gary Moore video "Emerald Aisles" on his return to Northern Ireland, he visits the castle and talks about the history of the castle. Cassette and CD versions of Gary Moore's 1989 album After the War feature an instrumental track titled "Dunluce" in one and two parts respectively.

- The castle is also the subject of a 1990s song named "Dunluce Castle" written by George Millar and sung by the Irish Rovers.

- The castle is mentioned and appears briefly in Michael Palin's 1994 episode of Great Railway Journeys, Derry to Kerry.

- The castle appeared as Snakehead's hideout under the name 'Ravens Keep' in the 2003 movie, The Medallion, which starred Jackie Chan.

- It is also featured on the cover of the album Glasgow Friday (2008) by American musician Jandek.

- The castle is the film location of the Game of Thrones Seat of House Greyjoy, the great castle of Pyke.The Old Bushmills Distillery is a distillery in Bushmills, County Antrim, Northern Ireland, owned by Casa Cuervo of Mexico. Bushmills Distillery uses water drawn from Saint Columb's Rill, which is a tributary of the River Bush. The distillery is a popular tourist attraction, with around 120,000 visitors per year.

The area has a long tradition with distillation. According to one story, as far back as 1276, an early settler called Sir Robert Savage of Ards, before defeating the Irish in battle, fortified his troops with "a mighty drop of acqua vitae".In 1608, a licence was granted to Sir Thomas Phillips by King James I to distil whiskey. The distillery in County Antrim.

The distillery in County Antrim.for the next seven years, within the countie of Colrane, otherwise called O Cahanes countrey, or within the territorie called Rowte, in Co. Antrim, by himselfe or his servauntes, to make, drawe, and distil such and soe great quantities of aquavite, usquabagh and aqua composita, as he or his assignes shall thinke fitt; and the same to sell, vent, and dispose of to any persons, yeeldinge yerelie the somme 13s 4d ...

The Bushmills Old Distillery Company itself was not established until 1784 by Hugh Anderson.Bushmills suffered many lean years with numerous periods of closure with no record of the distillery being in operation in the official records both in 1802 and in 1822. In 1860 a Belfast spirit merchant named Jame McColgan and Patrick Corrigan bought the distillery; in 1880 they formed a limited company. In 1885, the original Bushmills buildings were destroyed by fire but the distillery was swiftly rebuilt. In 1890, a steamship owned and operated by the distillery, SS Bushmills, made its maiden voyage across the Atlantic to deliver Bushmills whiskey to America. It called at Philadelphia and New York City before heading on to Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Yokohama. In the early 20th century, the U.S. was a very important market for Bushmills (and other Irish Whiskey producers). American Prohibition in 1920 came as a large blow to the Irish Whiskey industry, but Bushmills managed to survive. Wilson Boyd, Bushmills' director at the time, predicted the end of prohibition and had large stores of whiskey ready to export. After the Second World War, the distillery was bought by Isaac Wolfson, and, in 1972, it was taken over by Irish Distillers, meaning that Irish Distillers controlled the production of all Irish whiskey at the time. In June 1988, Irish Distillers was bought by French liquor group Pernod Ricard. In June 2005, the distillery was bought by Diageo for £200 million. Diageo have also announced a large advertising campaign in order to regain a market share for Bushmills. In May 2008, the Bank of Ireland issued a new series of sterling banknotes in Northern Ireland which all feature an illustration of the Old Bushmills Distillery on the obverse side, replacing the previous notes series which depicted Queen's University of Belfast. In November 2014 it was announced that Diageo had traded the Bushmills brand with Jose Cuervo in exchange for the 50% of the Don Julio brand of tequila that Diageo did not already own. -

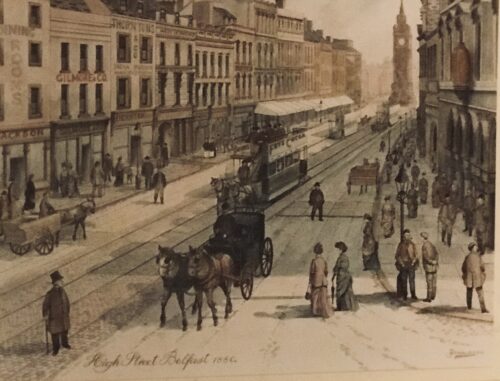

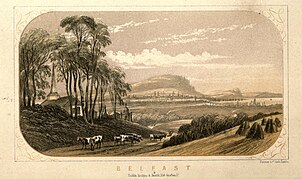

45cm x 55cm Belfast The history of Belfast as a settlement goes back to the Iron Age, but its status as a major urban centre dates to the 18th century. Belfast today is the capital of Northern Ireland. Belfast was throughout its modern history a major commercial and industrial centre, but the late 20th century saw a decline in its traditional industries, particularly shipbuilding. The city's history has been marked by violent conflict between Catholics and Protestants which has caused many working class areas of the city to be split into Catholic and Protestant areas. In recent years the city has been relatively peaceful and major redevelopment has occurred, especially in the inner city and dock areas. During the Great Famine, a potato blight that originated in America spread to Europe decimated crops in Ireland. A Belfast newspaper predicted the devastating effect the blight would have on the common people of Ireland, particularly in rural areas. The potato crop in 1845 largely failed all-over Ireland with the exception of the west coast and parts of Ulster. One-third of the crop was inedible and fears that those spuds in storage were contaminated were soon realized. In October 1846, a Belfast journal The Vindicator made an appeal on behalf of the starving, writing that their universal cry was "give us food or we perish". The publication went on to scold the United Kingdom for not meeting the basic needs of its people. By 1847, the British government were feeding 3 million famine victims a day, though many were still succumbing to disease brought on by starvation. Many of the poor moved eastward from rural areas into Belfast and Dublin, bringing with them famine-related diseases. Dr. Andrew Malcolm, who was working in Belfast at the time, wrote of the influx of the starving into the town, their horrific appearance and the "plague breath" they carried with them. The Belfast Newsletter reported in July 1847 that the town's hospitals were overflowing and that some of the emaciated were stretched out on the streets, dead or dying.On 10 July 1849, the Belfast Harbour commissioners, members of the council, gentry, merchants and the 13th Regiment officially opened the Victoria Channel aboard the royal steamer Prince of Wales. This new waterway allowed for large vessels to come up the River Lagan regardless of tide level. After a signal was given, a flotilla of sea craft moved up the channel to the adulation of the large crowds that had gathered to watch the event. The spectacle was concluded by a cannon salute and a resounding chorus of "Rule Britannia" by all those present.This new channel fed the growth of Belfast industry enabling new development, despite being completed during the last years of the Great Famine. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert along with the Prince of Wales visited Belfast in August 1849, sailing up Victoria Channel and venturing into the town. They were received jubilantly by the people of Belfast with fanfare and decorations adorning the streets. The Royal Family moved up High Street amidst rapturous cheers and well-wishing. On the same street, a 32-foot high arch had been built with a misspelled rendering of Irish Gaelic greeting "Céad Míle Fáilte" (a thousand welcomes) written on it. In the White Linen Hall, the Queen viewed an exhibition of Belfast's industrial goods. The Royals would make their way to the Lisburn Road and the Malone Turnpike where Victoria inspected the new Queen's College (later, University). After touring Mulholland's Mill, Victoria and her entourage returned to their vessel. Belfast was recovering from a cholera epidemic at the time of the Royal visit and many credited Victoria and Albert with lifting the spirits of the town during a difficult period.Conditions for the new working class were often squalid, with much of the population packed into overcrowded and unsanitary tenements. The city suffered from repeated cholera outbreaks in the mid-19th century. Though both Catholics and Protestants were often employed, Protestants would experience preferment over their Catholic counterparts. Hardly any of those in management were Catholic and Protestants would often receive promotion and desirable positions. Working class Catholics were the only group on the whole to experience adverse poverty during this period. Though there were Catholics and Protestants at all levels of society, it was often said "there are no Protestants in the slums". Conditions improved somewhat after a wholesale slum clearance programme in the 1900s. Belfast was becoming one of the greatest places for trade in the western world. In 1852, Belfast was the first port of Ireland, out pacing Dublin in both size, value and tonnage.[39] However, old sectarian tensions would soon come to the fore resulting in an almost annual cycle of summer rioting between Catholics and Protestants. On 12 July 1857, confrontations between crowds of Catholics and Protestants degraded into throwing stones on Albert Street with Catholics beating two Methodist ministers in the Millfield area with sticks. The next night, Protestants from Sandy Rowwent into Catholic areas, smashed windows and set houses on fire. The unrest turned into ten days of rioting, with many of the police force joining the Protestant side. There were also riots in Derry, Portadown and Lurgan. Firearms were produced with sporadic gunfire happening all over Belfast, the police could do little to mitigate the turmoil. The Riots of 1864 were so intense that reinforcements and two field guns were dispatched from Dublin Castle. A funeral for a victim of police gunfire was turned into a loyalist parade that unexpectedly went up through Donegall Place in the heart of Belfast. Police barely held as a barrier between the Protestants marching through Belfast's main streets and the irate Catholics who were massing at Castle Place. Continuous gunfire resounded throughout the city until a deluge of summer rain dispersed most of the crowd. The mud that was dredged up to dig the Victoria Channel was made into an artificial island, called Queen's Island, near east Belfast. Robert Hixon, an engineer from Liverpool who managed the arms work on Cromac Street, decided to use his surplus of iron ore to make ships. Hixon hired Edward Harlandfrom Newcastle-on-Tyne to assist in the endeavour. Harland launched his first ship in October 1855, his cutting-edge designs would go on to revolutionize the ship building world. In 1858, Harland would buy-out Hixon with the backing of Gustav Schwab. Schwab's nephew, Gustav Wolff had been working as an assistant to Harland. They formed the partnership of Harland & Wolff in 1861. Business was booming with the advent of American Civil War and the Confederacy purchasing steamers from Harland & Wolff. Gustav Schwab would go on to create the White Star Line in 1869, he ordered all of his ocean vessels from Harland & Wolff, setting the firm on the path to becoming the biggest ship building company in the world. Harland & Wolff would go on to build some of the world's most famous (and infamous) ships including HMHS Britannic, RMS Oceanic, RMS Olympic and, best known of all, the RMS Titanic.

45cm x 55cm Belfast The history of Belfast as a settlement goes back to the Iron Age, but its status as a major urban centre dates to the 18th century. Belfast today is the capital of Northern Ireland. Belfast was throughout its modern history a major commercial and industrial centre, but the late 20th century saw a decline in its traditional industries, particularly shipbuilding. The city's history has been marked by violent conflict between Catholics and Protestants which has caused many working class areas of the city to be split into Catholic and Protestant areas. In recent years the city has been relatively peaceful and major redevelopment has occurred, especially in the inner city and dock areas. During the Great Famine, a potato blight that originated in America spread to Europe decimated crops in Ireland. A Belfast newspaper predicted the devastating effect the blight would have on the common people of Ireland, particularly in rural areas. The potato crop in 1845 largely failed all-over Ireland with the exception of the west coast and parts of Ulster. One-third of the crop was inedible and fears that those spuds in storage were contaminated were soon realized. In October 1846, a Belfast journal The Vindicator made an appeal on behalf of the starving, writing that their universal cry was "give us food or we perish". The publication went on to scold the United Kingdom for not meeting the basic needs of its people. By 1847, the British government were feeding 3 million famine victims a day, though many were still succumbing to disease brought on by starvation. Many of the poor moved eastward from rural areas into Belfast and Dublin, bringing with them famine-related diseases. Dr. Andrew Malcolm, who was working in Belfast at the time, wrote of the influx of the starving into the town, their horrific appearance and the "plague breath" they carried with them. The Belfast Newsletter reported in July 1847 that the town's hospitals were overflowing and that some of the emaciated were stretched out on the streets, dead or dying.On 10 July 1849, the Belfast Harbour commissioners, members of the council, gentry, merchants and the 13th Regiment officially opened the Victoria Channel aboard the royal steamer Prince of Wales. This new waterway allowed for large vessels to come up the River Lagan regardless of tide level. After a signal was given, a flotilla of sea craft moved up the channel to the adulation of the large crowds that had gathered to watch the event. The spectacle was concluded by a cannon salute and a resounding chorus of "Rule Britannia" by all those present.This new channel fed the growth of Belfast industry enabling new development, despite being completed during the last years of the Great Famine. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert along with the Prince of Wales visited Belfast in August 1849, sailing up Victoria Channel and venturing into the town. They were received jubilantly by the people of Belfast with fanfare and decorations adorning the streets. The Royal Family moved up High Street amidst rapturous cheers and well-wishing. On the same street, a 32-foot high arch had been built with a misspelled rendering of Irish Gaelic greeting "Céad Míle Fáilte" (a thousand welcomes) written on it. In the White Linen Hall, the Queen viewed an exhibition of Belfast's industrial goods. The Royals would make their way to the Lisburn Road and the Malone Turnpike where Victoria inspected the new Queen's College (later, University). After touring Mulholland's Mill, Victoria and her entourage returned to their vessel. Belfast was recovering from a cholera epidemic at the time of the Royal visit and many credited Victoria and Albert with lifting the spirits of the town during a difficult period.Conditions for the new working class were often squalid, with much of the population packed into overcrowded and unsanitary tenements. The city suffered from repeated cholera outbreaks in the mid-19th century. Though both Catholics and Protestants were often employed, Protestants would experience preferment over their Catholic counterparts. Hardly any of those in management were Catholic and Protestants would often receive promotion and desirable positions. Working class Catholics were the only group on the whole to experience adverse poverty during this period. Though there were Catholics and Protestants at all levels of society, it was often said "there are no Protestants in the slums". Conditions improved somewhat after a wholesale slum clearance programme in the 1900s. Belfast was becoming one of the greatest places for trade in the western world. In 1852, Belfast was the first port of Ireland, out pacing Dublin in both size, value and tonnage.[39] However, old sectarian tensions would soon come to the fore resulting in an almost annual cycle of summer rioting between Catholics and Protestants. On 12 July 1857, confrontations between crowds of Catholics and Protestants degraded into throwing stones on Albert Street with Catholics beating two Methodist ministers in the Millfield area with sticks. The next night, Protestants from Sandy Rowwent into Catholic areas, smashed windows and set houses on fire. The unrest turned into ten days of rioting, with many of the police force joining the Protestant side. There were also riots in Derry, Portadown and Lurgan. Firearms were produced with sporadic gunfire happening all over Belfast, the police could do little to mitigate the turmoil. The Riots of 1864 were so intense that reinforcements and two field guns were dispatched from Dublin Castle. A funeral for a victim of police gunfire was turned into a loyalist parade that unexpectedly went up through Donegall Place in the heart of Belfast. Police barely held as a barrier between the Protestants marching through Belfast's main streets and the irate Catholics who were massing at Castle Place. Continuous gunfire resounded throughout the city until a deluge of summer rain dispersed most of the crowd. The mud that was dredged up to dig the Victoria Channel was made into an artificial island, called Queen's Island, near east Belfast. Robert Hixon, an engineer from Liverpool who managed the arms work on Cromac Street, decided to use his surplus of iron ore to make ships. Hixon hired Edward Harlandfrom Newcastle-on-Tyne to assist in the endeavour. Harland launched his first ship in October 1855, his cutting-edge designs would go on to revolutionize the ship building world. In 1858, Harland would buy-out Hixon with the backing of Gustav Schwab. Schwab's nephew, Gustav Wolff had been working as an assistant to Harland. They formed the partnership of Harland & Wolff in 1861. Business was booming with the advent of American Civil War and the Confederacy purchasing steamers from Harland & Wolff. Gustav Schwab would go on to create the White Star Line in 1869, he ordered all of his ocean vessels from Harland & Wolff, setting the firm on the path to becoming the biggest ship building company in the world. Harland & Wolff would go on to build some of the world's most famous (and infamous) ships including HMHS Britannic, RMS Oceanic, RMS Olympic and, best known of all, the RMS Titanic.Home Rule and the City Charter

In 1862 George Hamilton Chichester, 3rd Marquess of Donegall (a descendant of the Chichester family) built a new mansion on the slopes of Cavehill above the town. The named as the new Belfast Castle, it was designed by Charles Lanyon and construction was completed in 1870. By 1901, Belfast was the largest city in Ireland. The city's importance was evidenced by the construction of the lavish City Hall, completed in 1906. As noted, around 1840 its population included many Catholics, who originally settled in the west of city, around the area of today's Barrack Street which was known as the "Pound Loney". West Belfast remains the centre of the city's Catholic population (in contrast with the east of the city which remains predominantly Protestant). Other areas of Catholic settlement have included parts of the north of the city, especially Ardoyne and the Antrim Road, the Markets area immediately to the south of the city centre, and the Short Strand (a Catholic enclave in east Belfast). During the summer of 1872, about 30,000 Nationalists held a demonstration at Hannahstown in Belfast, campaigning for the release of Fenian prisoners, which lead to another series of riots between Catholics and Protestants. In 1874, the issue of Home Rule became mainstream in Irish politics, A conglomeration of MP's were denounced by the Belfast Newsletter on the eve of election, writing that "Home Rule was simply 'Rome Rule'" and that Protestants would not support a new Dublin parliament. In June 1886, Protestants celebrated the defeat of the First Home Rule Bill in the House of Commons, leading to rioting on the streets of Belfast and the deaths of seven people, with many more injured. In the same year, following The Twelfth Orange Institution parades, clashes took place between Catholics and Protestants, and also between Loyalists and police. Thirteen people were killed in a weekend of serious rioting which continued sporadically until mid-September with an official death toll of 31 people. Belfast City Hall during constructionAlthough the county borough of Belfast was created when it was granted city status by Queen Victoria in 1888,[42] the city continues to be viewed as straddling County Antrim and County Down with the River Lagan generally being seen as the line of demarcation.Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart made a grand visit to Belfast on behalf of the Queen to give it official recognition as a city. Belfast at this time was Ireland's largest city and the third most important port (behind London and Liverpool) in the United Kingdom; the leader in world trade at the time.Belfast had become a world class industrial city and the center of linen production for the whole planet. In 1896, a Second Home Rule Bill passed through the House of Commons but was struck down in the House of Lords. Wary Protestants celebrated and, as had happened 7 years earlier, Catholics took exception to Protestant triumphalism and rioted. On 14 January 1899, large crowds gathered to watch the launch of the RMS Oceanic which had been ordered by the White Star Line for the trans-Atlantic passenger travel. The Oceanic was the largest man-made moving object that had ever been built up to that time. By the year 1900, Belfast had the world's largest tobacco factory, tea machinery and fan-making works, handkerchief factory, dry dock and color Christmascard printers. Belfast was also the world's leading manufacturer of "fizzy drinks" (soft drinks). Belfast was by far the greatest economic beneficiary in Ireland of the Act of Union and Industrial Revolution. The city saw a bitter strike by dock workers organised by radical trade unionist Jim Larkin, in 1907. The dispute saw 10,000 workers on strike and a mutiny by the police, who refused to disperse the striker's pickets. Eventually the Army had to be deployed to restore order. The strike was a rare instance of non-sectarian mobilisation in Ulster at the time.

Belfast City Hall during constructionAlthough the county borough of Belfast was created when it was granted city status by Queen Victoria in 1888,[42] the city continues to be viewed as straddling County Antrim and County Down with the River Lagan generally being seen as the line of demarcation.Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart made a grand visit to Belfast on behalf of the Queen to give it official recognition as a city. Belfast at this time was Ireland's largest city and the third most important port (behind London and Liverpool) in the United Kingdom; the leader in world trade at the time.Belfast had become a world class industrial city and the center of linen production for the whole planet. In 1896, a Second Home Rule Bill passed through the House of Commons but was struck down in the House of Lords. Wary Protestants celebrated and, as had happened 7 years earlier, Catholics took exception to Protestant triumphalism and rioted. On 14 January 1899, large crowds gathered to watch the launch of the RMS Oceanic which had been ordered by the White Star Line for the trans-Atlantic passenger travel. The Oceanic was the largest man-made moving object that had ever been built up to that time. By the year 1900, Belfast had the world's largest tobacco factory, tea machinery and fan-making works, handkerchief factory, dry dock and color Christmascard printers. Belfast was also the world's leading manufacturer of "fizzy drinks" (soft drinks). Belfast was by far the greatest economic beneficiary in Ireland of the Act of Union and Industrial Revolution. The city saw a bitter strike by dock workers organised by radical trade unionist Jim Larkin, in 1907. The dispute saw 10,000 workers on strike and a mutiny by the police, who refused to disperse the striker's pickets. Eventually the Army had to be deployed to restore order. The strike was a rare instance of non-sectarian mobilisation in Ulster at the time. A 1907 stereoscope postcard depicting the construction of an ocean liner at the Harland and Wolff shipyard

A 1907 stereoscope postcard depicting the construction of an ocean liner at the Harland and Wolff shipyard -

38cm x 8cm Limerick City

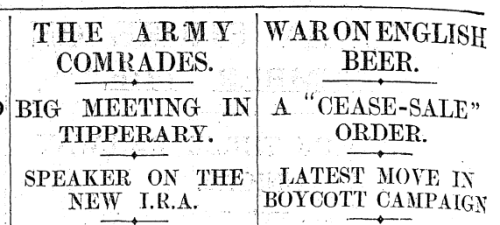

38cm x 8cm Limerick CityThe former beer of choice of An Taoiseach Bertie Ahern,the Bass Ireland Brewery operated on the Glen Road in West Belfast for 107 years until its closure in 2004.But despite its popularity, this ale would be the cause of bitter controversy in the 1930s as you can learn below.

Founded in 1777 by William Bass in Burton-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, England.The main brand was Bass Pale Ale, once the highest-selling beer in the UK.By 1877, Bass had become the largest brewery in the world, with an annual output of one million barrels.Its pale ale was exported throughout the British Empire, and the company's distinctive red triangle became the UK's first registered trade mark. In the early 1930s republicans in Dublin and elsewhere waged a campaign of intimidation against publicans who sold Bass ale, which involved violent tactics and grabbed headlines at home and further afield. This campaign occurred within a broader movement calling for the boycott of British goods in Ireland, spearheaded by the IRA. Bass was not alone a British product, but republicans took issue with Colonel John Gretton, who was chairman of the company and a Conservative politician in his day.In Britain,Ireland and the Second World War, Ian Woods notes that the republican newspaper An Phoblacht set the republican boycott of Bass in a broader context , noting that there should be “No British ales. No British sweets or chocolate. Shoulder to shoulder for a nationwide boycott of British goods. Fling back the challenge of the robber empire.”

In late 1932, Irish newspapers began to report on a sustained campaign against Bass ale, which was not strictly confined to Dublin. On December 5th 1932, The Irish Times asked:

Will there be free beer in the Irish Free State at the end of this week? The question is prompted by the orders that are said to have been given to publicans in Dublin towards the end of last week not to sell Bass after a specified date.

The paper went on to claim that men visited Dublin pubs and told publicans “to remove display cards advertising Bass, to dispose of their stock within a week, and not to order any more of this ale, explaining that their instructions were given in furtherance of the campaign to boycott British goods.” The paper proclaimed a ‘War on English Beer’ in its headline. The same routine, of men visiting and threatening public houses, was reported to have happened in Cork.

It was later reported that on November 25th young men had broken into the stores owned by Bass at Moore Lane and attempted to do damage to Bass property. When put before the courts, it was reported that the republicans claimed that “Colonel Gretton, the chairman of the company, was a bitter enemy of the Irish people” and that he “availed himself of every opportunity to vent his hate, and was an ardent supporter of the campaign of murder and pillage pursued by the Black and Tans.” Remarkably, there were cheers in court as the men were found not guilty, and it was noted that they had no intention of stealing from Bass, and the damage done to the premises amounted to less than £5.

A campaign of intimidation carried into January 1933, when pubs who were not following the boycott had their signs tarred, and several glass signs advertising the ale were smashed across the city. ‘BOYCOTT BRITISH GOODS’ was painted across several Bass advertisements in the city.

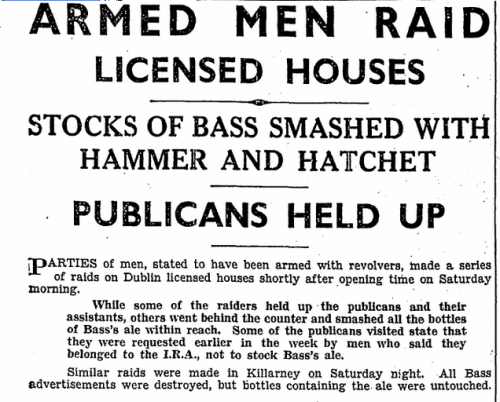

Throughout 1933, there were numerous examples of republicans entering pubs and smashing the supply of Bass bottles behind the counter. This activity was not confined to Dublin,as this report from late August shows. It was noted that the men publicly stated that they belonged to the IRA.

September appears to have been a particularly active period in the boycott, with Brian Hanley identifying Dublin, Tralee, Naas, Drogheda and Waterford among the places were publicans were targetted in his study The IRA: 1926-1936. One of the most interesting incidents occurring in Dun Laoghaire. There, newspapers reported that on September 4th 1933 “more than fifty young men marched through the streets” before raiding the premises of Michael Moynihan, a local publican. Bottles of Bass were flung onto the roadway and advertisements destroyed. Five young men were apprehended for their role in the disturbances, and a series of court cases nationwide would insure that the Bass boycott was one of the big stories of September 1933.

The young men arrested in Dun Laoghaire refused to give their name or any information to the police, and on September 8th events at the Dublin District Court led to police baton charging crowds. The Irish Times reported that about fifty supporters of the young men gathered outside the court with placards such as ‘Irish Goods for Irish People’, and inside the court a cry of ‘Up The Republic!’ led to the judge slamming the young men, who told him they did not recognise his court. The night before had seen some anti-Bass activity in the city, with the smashing of Bass signs at Burgh Quay. This came after attacks on pubs at Lincoln Place and Chancery Street. It wasn’t long before Mountjoy and other prisons began to home some of those involved in the Boycott Bass campaign, which the state was by now eager to suppress.

An undated image of a demonstration to boycott British goods. Credit: http://irishmemory.blogspot.ie/

This dramatic court appearance was followed by similar scenes in Kilmainham, where twelve men were brought before the courts for a raid on the Dead Man’s Pub, near to Palmerstown in West Dublin. Almost all in their 20s, these men mostly gave addresses in Clondalkin. Their court case was interesting as charges of kidnapping were put forward, as Michael Murray claimed the men had driven him to the Featherbed mountain. By this stage, other Bass prisoners had begun a hungerstrike, and while a lack of evidence allowed the men to go free, heavy fines were handed out to an individual who the judge was certain had been involved.

The decision to go on hungerstrike brought considerable attention on prisoners in Mountjoy, and Maud Gonne MacBride spoke to the media on their behalf, telling the Irish Press on September 18th that political treatment was sought by the men. This strike had begun over a week previously on the 10th, and by the 18th it was understood that nine young men were involved. Yet by late September, it was evident the campaign was slowing down, particularly in Dublin.

The controversy around the boycott Bass campaign featured in Dáil debates on several occasions. In late September Eamonn O’Neill T.D noted that he believed such attacks were being allowed to be carried out “with a certain sort of connivance from the Government opposite”, saying:

I suppose the Minister is aware that this campaign against Bass, the destruction of full bottles of Bass, the destruction of Bass signs and the disfigurement of premises which Messrs. Bass hold has been proclaimed by certain bodies to be a national campaign in furtherance of the “Boycott British Goods” policy. I put it to the Minister that the compensation charges in respect of such claims should be made a national charge as it is proclaimed to be a national campaign and should not be placed on the overburdened taxpayers in the towns in which these terrible outrages are allowed to take place with a certain sort of connivance from the Government opposite.

Another contribution in the Dáil worth quoting came from Daniel Morrissey T.D, perhaps a Smithwicks man, who felt it necessary to say that we were producing “an ale that can compare favourably with any ale produced elsewhere” while condemning the actions of those targeting publicans:

I want to say that so far as I am concerned I have no brief good, bad, or indifferent, for Bass’s ale. We are producing in this country at the moment—and I am stating this quite frankly as one who has a little experience of it—an ale that can compare favourably with any ale produced elsewhere. But let us be quite clear that if we are going to have tariffs or embargoes, no tariffs or embargoes can be issued or given effect to in this country by any person, any group of persons, or any organisation other than the Government elected by the people of the country.

Tim Pat Coogan claims in his history of the IRA that this boycott brought the republican movement into conflict with the Army Comrades Association, later popularly known as the ‘Blueshirts’. He claims that following attacks in Dublin in December 1932, “the Dublin vitners appealed to the ACA for protection and shipments of Bass were guarded by bodyguards of ACA without further incident.” Yet it is undeniable there were many incidents of intimidation against suppliers and deliverers of the product into 1933.

Not all republicans believed the ‘Boycott Bass’ campaign had been worthwhile. Patrick Byrne, who would later become secretary within the Republican Congress group, later wrote that this was a time when there were seemingly bigger issues, like mass unemployment and labour disputes in Belfast, yet:

In this situation, while the revolution was being served up on a plate in Belfast, what was the IRA leadership doing? Organising a ‘Boycott Bass’ Campaign. Because of some disparaging remarks the Bass boss, Colonel Gretton, was reported to have made about the Irish, some IRA leaders took umbrage and sent units out onto the streets of Dublin and elsewhere to raid pubs, terrify the customers, and destroy perfectly good stocks of bottled Bass, an activity in which I regret to say I was engaged.

Historian Brian Hanley has noted by late 1933 “there was little effort to boycott anything except Bass and the desperation of the IRA in hoping violence would revive the campaign was in fact an admission of its failure. At the 1934 convention the campaign was quietly abandoned.”

Interestingly, this wasn’t the last time republicans would threaten Bass. In 1986 The Irish Times reported that Bass and Guinness were both threatened on the basis that they were supplying to British Army bases and RUC stations, on the basis of providing a service to security forces.

Origins : Co Galway

Dimensions:35 cm x 45cm

-

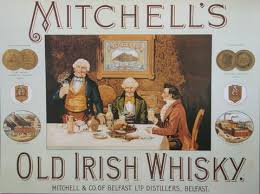

Mitchells Cruiskeen Lawn Old Irish Whiskey Advert. 48cm x 60cm Coleraine Co Antrim Once a giant of the distilling business along with Dunvilles,Mitchell’s fall from grace, like so many other superb Irish distilleries was symptomatic of the economic climate and circumstances of the time. Charles William Mitchell originated from Scotland and took over his fathers distillery in the Campletown area .In the 1860s he moved to Belfast and became manager of Dunvilles Whiskey before establishing his own brand Mitchell & Co tomb St in the late 1860s.A newspaper report in 1895 hailed the virtues of Mitchells Cruiskeen Lawn Whisky,which secured prizes around the world including first place at the New Orleans Exposition.It was a rare Mitchells Cruiskeen Lawn Whiskey mirror that recently commanded £11500 at auction in 2018 following the sale of the contents of an old Donegal public house. Indeed Mitchell’s were renowned for advertising their products on mirrors, trade cards, minature atlas books and pottery to name just a few. Below is the original mirror that was commissioned for their Tomb Street premises on the launch of their Cruiskeen Lawn Old Irish Whisky, late 1800’s. Two were made for the entrance of their Tomb Street premises. Inscribed is the Cruiskeen Lawn poem, with gold leaf barley with green and red in the Mitchell Crest. Definately the holy grail of all mirrors, a true treasure and still survives today in the heart of Belfast and worth the above mentioned princely sum and now probably more !

Mitchells Cruiskeen Lawn Old Irish Whiskey Advert. 48cm x 60cm Coleraine Co Antrim Once a giant of the distilling business along with Dunvilles,Mitchell’s fall from grace, like so many other superb Irish distilleries was symptomatic of the economic climate and circumstances of the time. Charles William Mitchell originated from Scotland and took over his fathers distillery in the Campletown area .In the 1860s he moved to Belfast and became manager of Dunvilles Whiskey before establishing his own brand Mitchell & Co tomb St in the late 1860s.A newspaper report in 1895 hailed the virtues of Mitchells Cruiskeen Lawn Whisky,which secured prizes around the world including first place at the New Orleans Exposition.It was a rare Mitchells Cruiskeen Lawn Whiskey mirror that recently commanded £11500 at auction in 2018 following the sale of the contents of an old Donegal public house. Indeed Mitchell’s were renowned for advertising their products on mirrors, trade cards, minature atlas books and pottery to name just a few. Below is the original mirror that was commissioned for their Tomb Street premises on the launch of their Cruiskeen Lawn Old Irish Whisky, late 1800’s. Two were made for the entrance of their Tomb Street premises. Inscribed is the Cruiskeen Lawn poem, with gold leaf barley with green and red in the Mitchell Crest. Definately the holy grail of all mirrors, a true treasure and still survives today in the heart of Belfast and worth the above mentioned princely sum and now probably more ! -

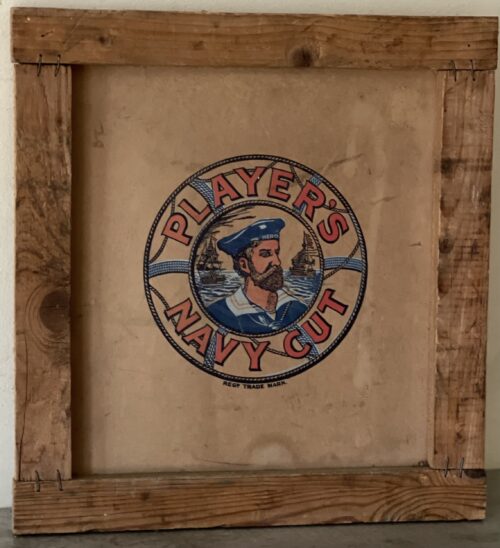

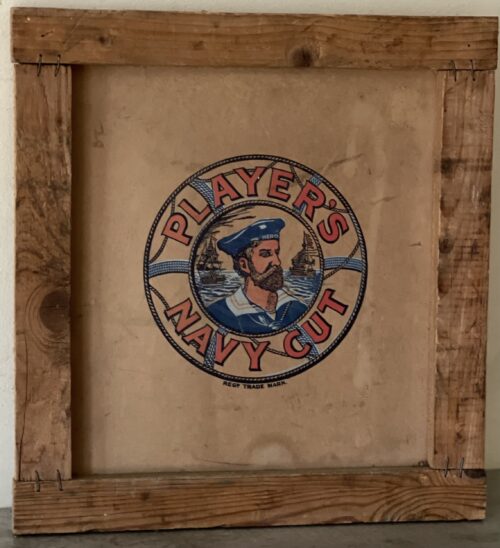

Very old & original Players Navy Cut Cigarettes Showcard (made from cardboard) 35cm x 35cm Virginia Co Cavan Navy Cut were a brand of cigarettes manufactured by Imperial Brands –formerly John Player & Sons– in Nottingham, England.The brand became "Player's Navy Cut". They were particularly popular in Britain,Ireland and Germany in the late 19th century and early part of the 20th century, but were later produced in the United States. The packet has the distinctive logo of a smoking sailor in a 'Navy Cut' cap. The phrase "Navy Cut" is according to Player's adverts to originate from the habit of sailors taking a mixture of tobacco leaves and binding them with string or twine. The tobacco would then mature under pressure and the sailor could then dispense the tobacco by slicing off a "cut".The product is also available in pipe tobacco form. The cigarettes were available in tins and the original cardboard container was a four sided tray of cigarettes that slid out from a covering like a classic matchbox. The next design had fold in ends so that the cigarettes could be seen or dispensed without sliding out the tray. In the 1950s the packaging moved to the flip top design like most brands. The image of the sailor was known as "Hero" because of the name on his hat band. It was first used in 1883 and the lifebuoy was added five years later. The sailor images were an 1891 artists concept registered for Chester-based William Parkins and Co for their "Jack Glory" brand.Behind the sailor are two ships. The one on the left is thought to be HMS Britannia and the one on the right HMS Dreadnought or HMS Hero. As time went by the image of the sailor changed as it sometimes had a beard and other times he was clean shaven. In 1927 "Hero" was standardised on a 1905 version. As part of the 1927 marketing campaign John Player and Sons commissioned an oil painting Head of a Sailor by Arthur David McCormick.The Player's Hero logo was thought to contribute to the cigarettes popularity in the 20s and 30s when competitor W.D. & H.O. Wills tried to create a similar image. Unlike Craven A, Navy Cut was intended to have a unisex appeal. Advertisements referred to "the appeal to Eve's fair daughters" and lines like "Men may come and Men may go".Hero is thought to have originally meant to indicate traditional British values, but his masculinity appealed directly to men and as a potential uncle figure for younger women. One slogan written inside the packet was "It's the tobacco that counts" and another was "Player's Please" which was said to appeal to the perceived desire of the population to be included in the mass market. The slogan was so well known that it was sufficient in a shop to get a packet of this brand. Player's Medium Navy Cut was the most popular by far of the three Navy Cut brands (there was also Mild and Gold Leaf). Two thirds of all the cigarettes sold in Britain were Players and two thirds of these was branded as Players Medium Navy Cut. In January 1937, Players sold nearly 3.5 million cigarettes (which included 1.34 million in London. The popularity of the brand was mostly amongst the middle class and in the South of England. While it was smoked in the north, other brands were locally more popular. The brand was discontinued in the UK in 2016.WWII cigarette packets exhibited at Monmouth Regimental Museumin 2012

Very old & original Players Navy Cut Cigarettes Showcard (made from cardboard) 35cm x 35cm Virginia Co Cavan Navy Cut were a brand of cigarettes manufactured by Imperial Brands –formerly John Player & Sons– in Nottingham, England.The brand became "Player's Navy Cut". They were particularly popular in Britain,Ireland and Germany in the late 19th century and early part of the 20th century, but were later produced in the United States. The packet has the distinctive logo of a smoking sailor in a 'Navy Cut' cap. The phrase "Navy Cut" is according to Player's adverts to originate from the habit of sailors taking a mixture of tobacco leaves and binding them with string or twine. The tobacco would then mature under pressure and the sailor could then dispense the tobacco by slicing off a "cut".The product is also available in pipe tobacco form. The cigarettes were available in tins and the original cardboard container was a four sided tray of cigarettes that slid out from a covering like a classic matchbox. The next design had fold in ends so that the cigarettes could be seen or dispensed without sliding out the tray. In the 1950s the packaging moved to the flip top design like most brands. The image of the sailor was known as "Hero" because of the name on his hat band. It was first used in 1883 and the lifebuoy was added five years later. The sailor images were an 1891 artists concept registered for Chester-based William Parkins and Co for their "Jack Glory" brand.Behind the sailor are two ships. The one on the left is thought to be HMS Britannia and the one on the right HMS Dreadnought or HMS Hero. As time went by the image of the sailor changed as it sometimes had a beard and other times he was clean shaven. In 1927 "Hero" was standardised on a 1905 version. As part of the 1927 marketing campaign John Player and Sons commissioned an oil painting Head of a Sailor by Arthur David McCormick.The Player's Hero logo was thought to contribute to the cigarettes popularity in the 20s and 30s when competitor W.D. & H.O. Wills tried to create a similar image. Unlike Craven A, Navy Cut was intended to have a unisex appeal. Advertisements referred to "the appeal to Eve's fair daughters" and lines like "Men may come and Men may go".Hero is thought to have originally meant to indicate traditional British values, but his masculinity appealed directly to men and as a potential uncle figure for younger women. One slogan written inside the packet was "It's the tobacco that counts" and another was "Player's Please" which was said to appeal to the perceived desire of the population to be included in the mass market. The slogan was so well known that it was sufficient in a shop to get a packet of this brand. Player's Medium Navy Cut was the most popular by far of the three Navy Cut brands (there was also Mild and Gold Leaf). Two thirds of all the cigarettes sold in Britain were Players and two thirds of these was branded as Players Medium Navy Cut. In January 1937, Players sold nearly 3.5 million cigarettes (which included 1.34 million in London. The popularity of the brand was mostly amongst the middle class and in the South of England. While it was smoked in the north, other brands were locally more popular. The brand was discontinued in the UK in 2016.WWII cigarette packets exhibited at Monmouth Regimental Museumin 2012 -

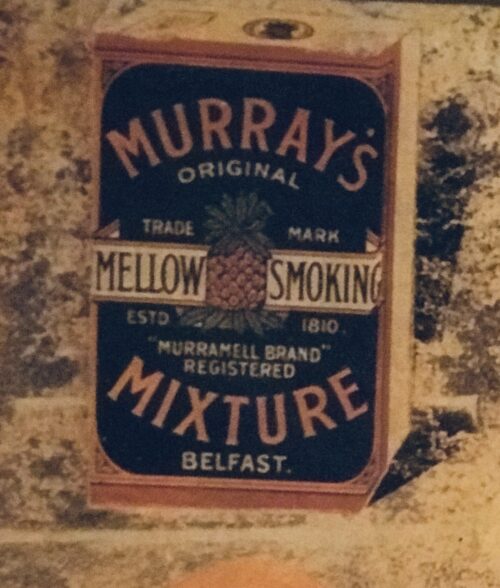

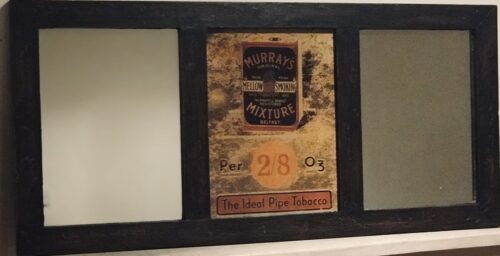

Murrays Original Pipe Strength Tobacco Advertising Mirror- Belfast 100cm x 50cm Murray, Sons and Company Ltd was a tobacco manufacturing company based in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The company traded under its own name but under various ownerships, from its foundation in 1810 until closure in 2005.

Murrays Original Pipe Strength Tobacco Advertising Mirror- Belfast 100cm x 50cm Murray, Sons and Company Ltd was a tobacco manufacturing company based in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The company traded under its own name but under various ownerships, from its foundation in 1810 until closure in 2005.History

Murray, Sons and Company Ltd began trading in Belfast in 1810, and became a limited company in 1884.By 1921, it shared most of the Belfast manufacture of tobacco, cigarettes and snuff with Gallaher Limited, who had moved to Belfast in 1867. Dunlop McCosh Cunningham took over the running of the works in the mid-1920s from his uncle. The firm produced the Erinmore and Yachtsman Navy Cut brands, though the cigarettes were not the superior quality that the pipe tobacco proved to be. The firm produced high quality popular pipe tobacco. For a time in the 1970s the Managing Director was Belfast man Mr Gleghorne and his personal assistant was Mrs Elizabeth Iris McDowell (née Hillock)Acquisition

In 1953, Murray, Sons and Company Ltd was acquired from Dunlop McCosh Cunningham by London-based Carreras Tobacco, which following the sale of shares in 1958 by the Baron family, merged with Rothman's of Pall Mall to become Carreras Rothmans Limited. Carreras Rothmans became known as Rothmans International in 1972. In June 1999, Rothmans International was acquired by British American Tobacco.Closure

In 2004, British American Tobacco announced the possible closure of Murray, Sons and Company Ltd and began a consultation process to review the plant's future. The company's fate was announced in January 2005, with the loss of 63 jobs.Brands

Throughout its trading life, Murray Sons and Company Ltd manufactured various brands of tobacco products including pipe tobacco:[5]- Craven

- Dunhill

- Erinmore

- Yachtsman Navy Cut

-

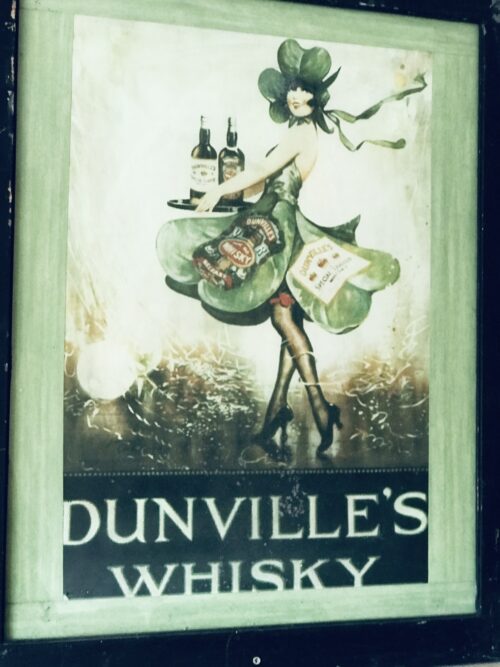

67cm x 52cm Dunville & Co Whisky Distillery was founded in Belfast Co Antrim in the 1820s,after initially gaining success as a whisky blender before constructing its own distillery.In 1837 Dunville began producing its most popular whiskey,Dunvilles VR.Athough Dunvilles was established and based in Ireland before partition and Irish Whiskey is normally spellt with an 'e',Dunvilles Whisky was always spelt without the vowel.

67cm x 52cm Dunville & Co Whisky Distillery was founded in Belfast Co Antrim in the 1820s,after initially gaining success as a whisky blender before constructing its own distillery.In 1837 Dunville began producing its most popular whiskey,Dunvilles VR.Athough Dunvilles was established and based in Ireland before partition and Irish Whiskey is normally spellt with an 'e',Dunvilles Whisky was always spelt without the vowel. -

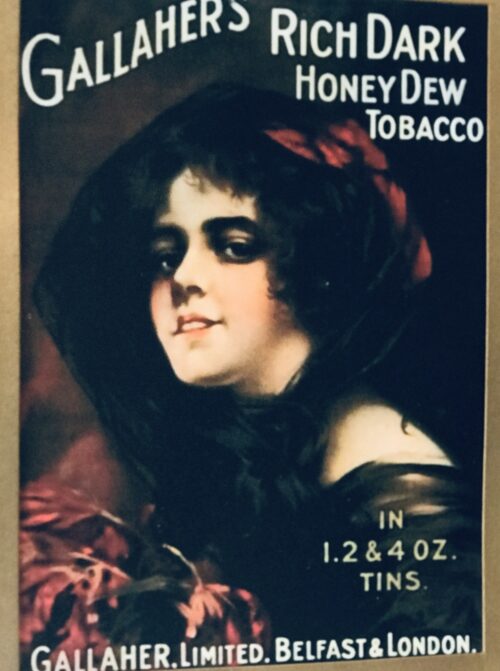

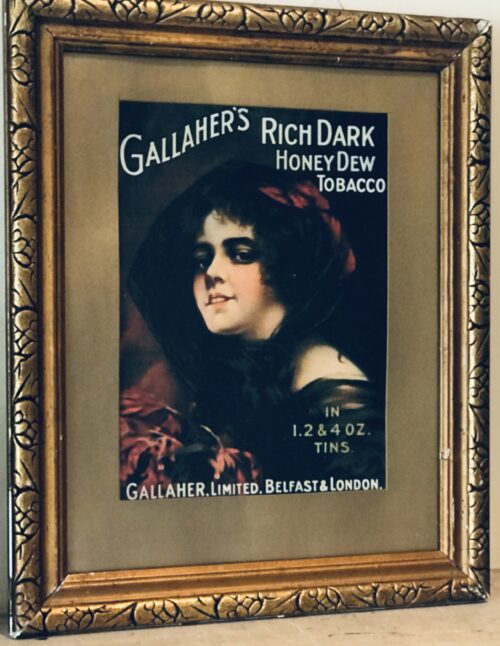

Nicely framed Gallahers tobacco advertising print featuring that mysterious dark haired beauty tempting the men of the day to part with their hard earned cash and choose Gold Plate cigarettes or rich dark honey dew tobacco for their pipes. 38cm x 30cmThomas Gallaher (1840 – 1927) was the son of a prosperous Protestant miller who owned the Templemoyle Grain Mills in Eglinton, Londonderry, Northern Ireland.Gallaher served an apprenticeship with Robert Bond, a general merchant on Shipquay Street, Londonderry, in the early 1850s.Gallaher borrowed £200 from his parents and opened a tobacconist business at 7 Sackville Street, Londonderry, in 1857. He manufactured and sold Irish roll pipe tobacco. The expanding business was relocated to Belfast from 1863.A five-storey factory employing 600 people was built at York Road, Belfast in 1881.A factory was opened at 60 Holborn Viaduct in London in 1888, followed by a Clerkenwell factory a year later.The firm was converted into a limited liability company with a capital of £1 million in 1896.A new £100,000 factory across seven acres was opened in Belfast in 1897. It was probably the largest tobacco manufacturing plant in the world.Park Drive, a machine-made cigarette brand, was introduced from 1902.Thomas Gallaher declined to join the great tobacco combines of the age, Imperial Tobacco and the American Tobacco Company, and consequently he controlled the largest independent tobacco company in the world by 1903.Gallaher bought his raw materials directly, and by cutting out the middleman he was able to keep his costs low. He was the largest independent purchaser of American tobacco in the world by 1906, and bought only the highest grade of crop. The atmosphere at the Belfast factory was described as familial. Midday meals were served at cost-price. Gallaher was the first man in Belfast to reduce working hours from 57 to 47 a week. The company employed 3,000 people by 1907.Gallaher acquired the six acre Great Brunswick Street premises of the Dublin City Distillery for £20,000 in 1908. There, he built a large tobacco factory.At York Street, Belfast, Gallaher established what was, by 1914, one of the largest tobacco factories in the world. The company also owned extensive plantations in Virginia.

Nicely framed Gallahers tobacco advertising print featuring that mysterious dark haired beauty tempting the men of the day to part with their hard earned cash and choose Gold Plate cigarettes or rich dark honey dew tobacco for their pipes. 38cm x 30cmThomas Gallaher (1840 – 1927) was the son of a prosperous Protestant miller who owned the Templemoyle Grain Mills in Eglinton, Londonderry, Northern Ireland.Gallaher served an apprenticeship with Robert Bond, a general merchant on Shipquay Street, Londonderry, in the early 1850s.Gallaher borrowed £200 from his parents and opened a tobacconist business at 7 Sackville Street, Londonderry, in 1857. He manufactured and sold Irish roll pipe tobacco. The expanding business was relocated to Belfast from 1863.A five-storey factory employing 600 people was built at York Road, Belfast in 1881.A factory was opened at 60 Holborn Viaduct in London in 1888, followed by a Clerkenwell factory a year later.The firm was converted into a limited liability company with a capital of £1 million in 1896.A new £100,000 factory across seven acres was opened in Belfast in 1897. It was probably the largest tobacco manufacturing plant in the world.Park Drive, a machine-made cigarette brand, was introduced from 1902.Thomas Gallaher declined to join the great tobacco combines of the age, Imperial Tobacco and the American Tobacco Company, and consequently he controlled the largest independent tobacco company in the world by 1903.Gallaher bought his raw materials directly, and by cutting out the middleman he was able to keep his costs low. He was the largest independent purchaser of American tobacco in the world by 1906, and bought only the highest grade of crop. The atmosphere at the Belfast factory was described as familial. Midday meals were served at cost-price. Gallaher was the first man in Belfast to reduce working hours from 57 to 47 a week. The company employed 3,000 people by 1907.Gallaher acquired the six acre Great Brunswick Street premises of the Dublin City Distillery for £20,000 in 1908. There, he built a large tobacco factory.At York Street, Belfast, Gallaher established what was, by 1914, one of the largest tobacco factories in the world. The company also owned extensive plantations in Virginia. Gallaher continued to work at his desk every day until a few months before he died in 1927. He was remembered as a courteous, kindly man, a generous employer, and an extremely talented businessman. His plain ways endeared him to people. He left an estate valued at £503,954.The company was principally inherited by his nephew, John Gallaher Michaels (1880 – 1948). Michaels had worked for his uncle for many years, and had been manger of the American operations.The Constructive Finance & Investment Co, led by Edward de Stein (1887 – 1965), acquired the entire share capital of Gallaher for several million pounds in 1929, and offered shares to the public.Why Michaels divested his stake in Gallaher remains unclear, but he, his uncle and his brother all lacked heirs, so perhaps he simply wished to retire and pass on management of the company to others.A new factory was established at East Wall, Dublin for £250,000 in 1929. The East Wall factory was closed with the loss of 400 jobs, following the introduction of a tariff on businesses not majority-owned by Irish residents, in 1932.Imperial Tobacco acquired 51 percent of Gallaher for £1.25 million in 1932. Gallaher retained its managerial independence, and the Imperial Tobacco move was executed with the intention of blocking a potential bid for Gallaher from the American Tobacco Company.Gallaher was the fourth largest cigarette manufacturer in Britain by 1932.Gallaher acquired Peter Jackson in 1934. The firm manufactured Du Maurier cigarettes, which was the first popular filter-tip brand in Britain.E Robinson & Son, manufacturers of Senior Service cigarettes, was acquired in 1937. Senior Service had been highly successful within the Manchester area, but Robinson’s had lacked the capital to take the brand nationwide.

J Freeman & Son, cigar manufacturers of Cardiff, was acquired in 1947.Gallaher acquired Cope Brothers of Liverpool, owners of the Old Holborn brand, in 1952.Benson & Hedges was acquired, mainly for the prestigious brand name, in 1955.Gallaher sales grew rapidly in the 1950s. Senior Service and Park Drive became respectively the third and fourth highest selling cigarettes in Britain in 1959, by which time Gallaher held 30 percent of the British tobacco market.Gallaher acquired J Wix & Sons Ltd, the fast-growing manufacturer of Kensitas cigarettes, from the American Tobacco Company in 1961.The Imperial Tobacco stake in Gallaher had been diluted to 37 percent by 1961.

Gallaher claimed 37 percent of the British cigarette market by 1962.A large factory was established at Airton Road, Dublin in 1963.Silk Cut was launched as a low-tar brand in 1964.

Gallaher employed 15,000 people in 1965, and had an authorised capital of £45 million in 1968. The company held 27 percent of the British tobacco market in 1968.Benson & Hedges was the leading king-size cigarette brand in Britain by 1981.The Belfast factory was closed in 1988. 700 jobs were lost, and production was relocated to Ballymena in County Antrim.

A cigar factory in Port Talbot, Wales was closed with the loss of 370 jobs in 1994.The Manchester cigarette factory was closed in 2000-1. Nearly 1,000 jobs were lost. Production was transferred to Ballymena, where 300 extra jobs were created.Japan Tobacco acquired Gallaher, by then the fifth largest tobacco company in the world, for £7.5 billion in cash in 2007.Ballymena, the last remaining tobacco factory in the UK, was closed in 2017, with production relocated to Eastern Europe. 860 jobs were lost.

Gallaher continued to work at his desk every day until a few months before he died in 1927. He was remembered as a courteous, kindly man, a generous employer, and an extremely talented businessman. His plain ways endeared him to people. He left an estate valued at £503,954.The company was principally inherited by his nephew, John Gallaher Michaels (1880 – 1948). Michaels had worked for his uncle for many years, and had been manger of the American operations.The Constructive Finance & Investment Co, led by Edward de Stein (1887 – 1965), acquired the entire share capital of Gallaher for several million pounds in 1929, and offered shares to the public.Why Michaels divested his stake in Gallaher remains unclear, but he, his uncle and his brother all lacked heirs, so perhaps he simply wished to retire and pass on management of the company to others.A new factory was established at East Wall, Dublin for £250,000 in 1929. The East Wall factory was closed with the loss of 400 jobs, following the introduction of a tariff on businesses not majority-owned by Irish residents, in 1932.Imperial Tobacco acquired 51 percent of Gallaher for £1.25 million in 1932. Gallaher retained its managerial independence, and the Imperial Tobacco move was executed with the intention of blocking a potential bid for Gallaher from the American Tobacco Company.Gallaher was the fourth largest cigarette manufacturer in Britain by 1932.Gallaher acquired Peter Jackson in 1934. The firm manufactured Du Maurier cigarettes, which was the first popular filter-tip brand in Britain.E Robinson & Son, manufacturers of Senior Service cigarettes, was acquired in 1937. Senior Service had been highly successful within the Manchester area, but Robinson’s had lacked the capital to take the brand nationwide.

J Freeman & Son, cigar manufacturers of Cardiff, was acquired in 1947.Gallaher acquired Cope Brothers of Liverpool, owners of the Old Holborn brand, in 1952.Benson & Hedges was acquired, mainly for the prestigious brand name, in 1955.Gallaher sales grew rapidly in the 1950s. Senior Service and Park Drive became respectively the third and fourth highest selling cigarettes in Britain in 1959, by which time Gallaher held 30 percent of the British tobacco market.Gallaher acquired J Wix & Sons Ltd, the fast-growing manufacturer of Kensitas cigarettes, from the American Tobacco Company in 1961.The Imperial Tobacco stake in Gallaher had been diluted to 37 percent by 1961.

Gallaher claimed 37 percent of the British cigarette market by 1962.A large factory was established at Airton Road, Dublin in 1963.Silk Cut was launched as a low-tar brand in 1964.

Gallaher employed 15,000 people in 1965, and had an authorised capital of £45 million in 1968. The company held 27 percent of the British tobacco market in 1968.Benson & Hedges was the leading king-size cigarette brand in Britain by 1981.The Belfast factory was closed in 1988. 700 jobs were lost, and production was relocated to Ballymena in County Antrim.

A cigar factory in Port Talbot, Wales was closed with the loss of 370 jobs in 1994.The Manchester cigarette factory was closed in 2000-1. Nearly 1,000 jobs were lost. Production was transferred to Ballymena, where 300 extra jobs were created.Japan Tobacco acquired Gallaher, by then the fifth largest tobacco company in the world, for £7.5 billion in cash in 2007.Ballymena, the last remaining tobacco factory in the UK, was closed in 2017, with production relocated to Eastern Europe. 860 jobs were lost.

-

Great piece of Gaelic football Nostalgia here as Meath captain lifts the Sam Maguire on the occasion of the Royal county's first All Ireland Football success in 1949. Origins: Dunboyne Co Meath Dimensions :26cm x 32cm. Glazed

Great piece of Gaelic football Nostalgia here as Meath captain lifts the Sam Maguire on the occasion of the Royal county's first All Ireland Football success in 1949. Origins: Dunboyne Co Meath Dimensions :26cm x 32cm. GlazedAll-Ireland football final day, 1949. Meath fans are en route to Croke Park by steam train, and will see their county win its first championship. They stop at Dunboyne. He hears their cheers fall through the billowing steam from the railway bridge. Five-year-old Seán Boylan knows something big is stirring.

Then he was simply a small boy kicking a ball around the family garden. The green and gold throng roared encouragement through fellowship and goodwill, buoyed by the occasion.

In later years he would give them good cause to cheer. Just a snapshot, but the moment seems to have acquired a near-cinematic resonance through what it prefigured. That railway bridge is now known locally as Boylan's bridge.

Around Dunboyne, there were local heroes to fire the imagination. His neighbours included Meath players like Jimmy Reilly, Bobby Ruske and 1949 All-Ireland-winning captain Brian Smyth.

"Brian Smyth was a great friend of my father's. I have a memory of kicking a ball around with him in the run-up to the 1954 All-Ireland final.

"He'd call out to the house on a Wednesday night to Daddy, getting the brews. Brian had a very famous dummy and he showed me how to do it. Of course, I practised it and used it all my life after."

He drew inspiration, too, from further afield. The great Gaelic names of his childhood were lent further mystique by Micheál O'Hehir's radio commentaries, which painted bold pictures in his head.

The legends were remote yet vividly present through the voice piercing the static.

"When he was doing matches you'd swear you were at the game. You were trying to be a John Dowling or a Seán Purcell or a Bobby or Nicky Rackard, a Christy Ring when you heard the way he described it."

Not that Gaelic games alone dominated his formative years. Motor races held in Dunboyne thrilled him as a youngster. Even now, his heart quickens a little at the vroom-vrooming of racing engines.

"I was always mad into motorsport, but most kids around Dunboyne were, because you had the racing which started in the '50s.

"It was outside your door so you followed the motorbikes and the cars. Of course, the only thing you could afford to do yourself was the go-karting. You'd go across to Monasterboice, where there was a track, or down to Askeaton in Limerick. The bug is still there."

At the age of nine, he was sent to Belvedere College. Rugby, of course, was on the sporting curriculum and he played with enthusiasm, once certain positional difficulties had been resolved.

"At the time the Ban was in but I played for a few years. In the first match I played I was put in the secondrow. At my height! I ended up in the backs afterwards, but it was very funny."

He chuckles at the thought of himself as a secondrow forward. In later years he was to meet Peter Stringer after an Ireland international. The scrumhalf greeted him warmly, announcing he was delighted to meet someone even smaller than himself.

His participation in rugby at Belvedere was never questioned, despite his GAA and republican family background. He was left to find his own course.

"My father, Lord be good to him, never tried to influence me in any way with regard to what I would play or what I became involved in. He wasn't that sort of man. And, well, in Belvedere, you're talking about the place where Kevin Barry went to school."

He took two of his boys in to see the old alma mater a few years back and was touched at the reception he received.

"I said I'd see if the then headmaster, Fr Leonard Moloney, was around. I hadn't been back in the place much but he invited us into his office. He went over to the press and took out two Club Lemons and two Mars bars for the lads. From then on that was the only school they wanted to go to and they're there now."

He hurled too at Belvedere, but his education in Gaelic games was to be furthered at Clogher Road Vocational School in Crumlin, which he attended after leaving Belvedere at 15. Moving from the privileged halls of Belvedere to the earthier environment of his new school was a jolt, but football and hurling helped smooth the transition.

In Crumlin, he would learn how to use his hands, within and without the classroom.

"The big thing there was the sport end of it. It was Gaelic and soccer we played. The PE instructor was Jim McCabe, who played centre-half back on the Cavan team that won the All-Ireland in 1952. He was still playing for Cavan at this stage. He was a lovely man and a terrific shooter."

He found himself spending Wednesday afternoons kicking a ball around with McCabe and another Cavan player, Charlie Gallagher. The latter's patiently rigorous application to practising his free-taking left a deep impression on the manager of the future.

While at Clogher Road, he represented Dublin Vocational Schools at centre-half back in both hurling and football. The goalkeeper on the football team was Pat Dunne, who would later play with Manchester United and Ireland.

He was on the move again at 16, switching to Warrenstown Agricultural College near Trim. His family background working with the land made the choice seem logical. Besides, the college did a nice sideline in cultivating footballers and hurlers. Again, he found an All-Ireland-winner circling prominently within his youthful orbit, foreshadowing his own relationship with Sam Maguire.