-

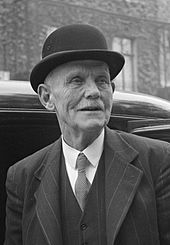

Atmospheric photograph of a moustached Michael Collins meeting the Kilkenny hurling team in advance of the 1921 Leinster hurling final, played at Croke Park on September 11, 1921. Dublin won the match on the score of Dublin 4-04 Kilkenny 1-05. 30cm x 40cm Durrow Co Laois Michael Collins was a revolutionary, soldier and politician who was a leading figure in the early-20th-century Irish struggle for independence. He was Chairman of the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State from January 1922 until his assassination in August 1922. Collins was born in Woodfield, County Cork, the youngest of eight children, and his family had republican connections reaching back to the 1798 rebellion. He moved to London in 1906, to become a clerk in the Post Office Savings Bank at Blythe House. He was a member of the London GAA, through which he became associated with the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Gaelic League. He returned to Ireland in 1916 and fought in the Easter Rising. He was subsequently imprisoned in the Frongoch internment camp as a prisoner of war, but was released in December 1916. Collins rose through the ranks of the Irish Volunteers and Sinn Féin after his release from Frongoch. He became a Teachta Dála for South Cork in 1918, and was appointed Minister for Finance in the First Dáil. He was present when the Dáil convened on 21 January 1919 and declared the independence of the Irish Republic. In the ensuing War of Independence, he was Director of Organisation and Adjutant General for the Irish Volunteers, and Director of Intelligence of the Irish Republican Army. He gained fame as a guerrilla warfare strategist, planning and directing many successful attacks on British forces, such as the assassination of key British intelligence agents in November 1920. After the July 1921 ceasefire, Collins and Arthur Griffith were sent to London by Éamon de Valera to negotiate peace terms. The resulting Anglo-Irish Treaty established the Irish Free State but depended on an Oath of Allegiance to the Crown, a condition that de Valera and other republican leaders could not reconcile with. Collins viewed the Treaty as offering "the freedom to achieve freedom", and persuaded a majority in the Dáil to ratify the Treaty. A provisional government was formed under his chairmanship in early 1922 but was soon disrupted by the Irish Civil War, in which Collins was commander-in-chief of the National Army. He was shot and killed in an ambush by anti-Treaty on 22nd August 1922.

Atmospheric photograph of a moustached Michael Collins meeting the Kilkenny hurling team in advance of the 1921 Leinster hurling final, played at Croke Park on September 11, 1921. Dublin won the match on the score of Dublin 4-04 Kilkenny 1-05. 30cm x 40cm Durrow Co Laois Michael Collins was a revolutionary, soldier and politician who was a leading figure in the early-20th-century Irish struggle for independence. He was Chairman of the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State from January 1922 until his assassination in August 1922. Collins was born in Woodfield, County Cork, the youngest of eight children, and his family had republican connections reaching back to the 1798 rebellion. He moved to London in 1906, to become a clerk in the Post Office Savings Bank at Blythe House. He was a member of the London GAA, through which he became associated with the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Gaelic League. He returned to Ireland in 1916 and fought in the Easter Rising. He was subsequently imprisoned in the Frongoch internment camp as a prisoner of war, but was released in December 1916. Collins rose through the ranks of the Irish Volunteers and Sinn Féin after his release from Frongoch. He became a Teachta Dála for South Cork in 1918, and was appointed Minister for Finance in the First Dáil. He was present when the Dáil convened on 21 January 1919 and declared the independence of the Irish Republic. In the ensuing War of Independence, he was Director of Organisation and Adjutant General for the Irish Volunteers, and Director of Intelligence of the Irish Republican Army. He gained fame as a guerrilla warfare strategist, planning and directing many successful attacks on British forces, such as the assassination of key British intelligence agents in November 1920. After the July 1921 ceasefire, Collins and Arthur Griffith were sent to London by Éamon de Valera to negotiate peace terms. The resulting Anglo-Irish Treaty established the Irish Free State but depended on an Oath of Allegiance to the Crown, a condition that de Valera and other republican leaders could not reconcile with. Collins viewed the Treaty as offering "the freedom to achieve freedom", and persuaded a majority in the Dáil to ratify the Treaty. A provisional government was formed under his chairmanship in early 1922 but was soon disrupted by the Irish Civil War, in which Collins was commander-in-chief of the National Army. He was shot and killed in an ambush by anti-Treaty on 22nd August 1922. -

Lovely original drawing of the famous NH mare Dawn Run 20cm x 23cm Bagenalstown Co Carlow Dawn Run (1978–1986) was an Irish Thoroughbred racehorse (Deep Run - Twilight Slave) who was the most successful racemare in the history of National Hunt racing. She won the Champion Hurdle at the Cheltenham Festival in 1984 and the Cheltenham Gold Cup over fences at the festival in 1986. Dawn Run was the only racehorse ever to complete the Champion Hurdle - Gold Cup double. She was only the second mare to win the Champion Hurdle (and one of only four to win it in total), and one of only four who have won the Cheltenham Gold Cup. She was the only horse ever to complete the English, Irish and French Champion Hurdle treble. A daughter of the highly successful National Hunt sire Deep Run, Dawn Run was bought for 5,800 guineas and trained by Paddy Mullins in Ireland.

Lovely original drawing of the famous NH mare Dawn Run 20cm x 23cm Bagenalstown Co Carlow Dawn Run (1978–1986) was an Irish Thoroughbred racehorse (Deep Run - Twilight Slave) who was the most successful racemare in the history of National Hunt racing. She won the Champion Hurdle at the Cheltenham Festival in 1984 and the Cheltenham Gold Cup over fences at the festival in 1986. Dawn Run was the only racehorse ever to complete the Champion Hurdle - Gold Cup double. She was only the second mare to win the Champion Hurdle (and one of only four to win it in total), and one of only four who have won the Cheltenham Gold Cup. She was the only horse ever to complete the English, Irish and French Champion Hurdle treble. A daughter of the highly successful National Hunt sire Deep Run, Dawn Run was bought for 5,800 guineas and trained by Paddy Mullins in Ireland.Flat and Hurdle races

She started her career at the age of four, running in flat races at provincial courses. She was ridden in her first three races by her 62-year-old owner, Charmian Hill. After completing a hat-trick of wins on the flat, she set out on her hurdling career and progressed through the ranks to become champion novice hurdler in Britain and Ireland. In her second season, she won eight of her nine races, including the English Champion Hurdle at Cheltenham, the Irish Champion Hurdle at Leopardstown, both over two miles, and the French Champion Hurdle (Grande Course de Haies d'Auteuil) at Auteuil over three miles, becoming the first horse to complete the treble. Her other big victories that season included the Christmas Hurdle (2 miles) at Kempton, in which she beat the reigning Champion Hurdler Gaye Brief by a neck after a duel up the home stretch, the Sandemans Hurdle at Aintree Racecourse (2 miles 5½ furlongs), which she won in a canter by fifteen lengths, and the Prix La Barka at Auteuil.Steeplechases

She turned to steeplechasing but was injured after winning her first race and was out of action for the rest of the season. She made a successful return in December 1985 by winning the Durkan Brothers Chase at Punchestown by eight lengths. She followed up by beating the subsequent two mile champion chaser Buck House over two and a half miles at Leopardstown later the same month despite making a bad mistake at the last fence. She was a hot favourite to win that season's Cheltenham Gold Cup, despite the fact that no horse had ever completed the Champion Hurdle, Gold Cup double, she was still virtually a novice over fences, and the three and a quarter mile trip of the Gold Cup over the stiff Cheltenham course was further than she had ever run before. In January 1986, she was given a prep race at Cheltenham, which she was expected to win easily. Her usual jockey, Tony Mullins, the son of the trainer, was on board. As usual, she set out to make all the running but her inexperience showed as she made a mistake on the back straight and unshipped her jockey. The commentator Julian Wilson had just spent about 30 seconds effusively praising her performance, "cruising, coasting in the lead", "it's two years since she's been beaten". Mullins got back up on her and finished the course, last of the four runners. It was an unsatisfactory preparation for the Cheltenham Gold Cup, but, despite her inexperience, it was decided to let her take her chance. Controversially, and against the wishes of the trainer, Tony Mullins was replaced for the Gold Cup by the top jockey of the time, Jonjo O'Neill.On the day, Dawn Run started hot favourite. O'Neill set her out in front to make the running as usual, but she was harried throughout the first circuit by Run and Skip. Unsettled by the attention, Dawn Run made a bad mistake at the water jump and lost two lengths and her momentum. She won back the lead at the next fence but made another bad mistake at the last ditch and was clearly under pressure as the field made their way down hill to the third last. At this stage, there were only four horses in contention: Dawn Run, Run and Skip, the previous year's Gold Cup winner Forgive ´n Forget, and Wayward Lad, who had won the King George VI Chase three times. As Dawn Run led the field into the straight with just two fences and the uphill finish ahead of them, a huge cheer went up from the crowd, but Wayward Lad and Forgive ´n Forget swept past the mare. O'Neill drove her up to the second last and got such a response that she landed in front. It appeared to be a futile effort, however, as Wayward Lad regained the lead coming to the last fence, pressed by Forgive ´n Forget with Dawn Run struggling in third. About a hundred yards out, Wayward Lad began to hang to the left as his stamina started to give out. O'Neill switched Dawn Run to the outside, and they raced past Forgive ´n Forget and cut into Wayward Lad's lead. Yards from the finish, they caught him and passed the post three quarters of a length ahead. They had won in record time. The huge crowd then invaded the winners' enclosure to join in the celebrations. In her next race at Aintree, Dawn Run failed to get past the first fence, but followed up by again beating Buck House in a specially arranged match over two miles at the Punchestown Festival. The decision was then made by her owner to send her back to France to try to repeat her 1984 win in the Grande Course de Haies d'Auteuil (French Champion Hurdle). French jockey Michel Chirol was on board Dawn Run. In that race, she fell while going well at a hurdle on the back straight, the fifth last, and never got up, having broken her neck. Her death at age 8, while barely into her prime as a steeplechaser, was hugely mourned by the racing public. It was reported on the front page of the following day's Irish Times, and her statue adorns the parade ring at Cheltenham, opposite the statue of Arkle. -

19cm x 25cm Ennistymon Co Clare Sometimes its an eclectic or seemingly incongruous picture or photograph that one remembers a certain pub by.This photo hung for years in a public house in Ennistymon,right at the corner of the bar and beside the cash register.There is a strong sense of melancholy and nostalgia about it and here it isn now ,waiting for its next home !

19cm x 25cm Ennistymon Co Clare Sometimes its an eclectic or seemingly incongruous picture or photograph that one remembers a certain pub by.This photo hung for years in a public house in Ennistymon,right at the corner of the bar and beside the cash register.There is a strong sense of melancholy and nostalgia about it and here it isn now ,waiting for its next home ! -

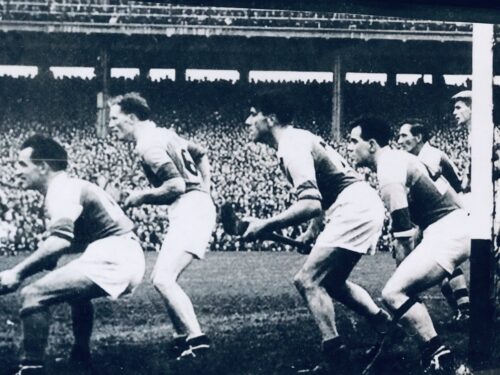

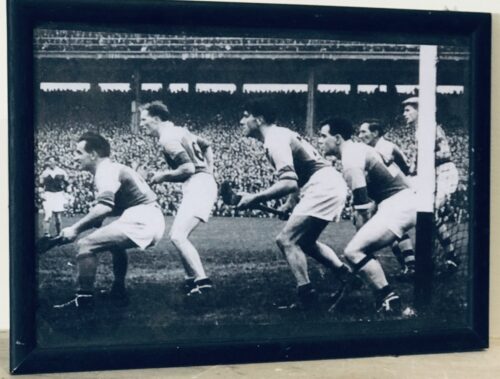

26cm x 33cm Ferns Co Wexford An anxious looking Wexford defence prepare as Christy Ring takes a in the 1956 All Ireland Hurling Final.The result would be forever known simply as " The Save ". Art Foley, who died on Monday last in New York, will be remembered for a save he made in the closing stages of the 1956 All-Ireland hurling final that had seismic and far-reaching consequences. It formed an instrumental part of a metamorphic sequence of play in a terrific contest with Cork, leading to one of the game's most epic finales. With three minutes left the ever-threatening Christy Ring gained possession and made for the Wexford goal. The finer points of what happened next are still in dispute. The main thread of the narrative is not. Ring let fly and the diminutive Foley in Wexford's goal was equal to it. He needed to be. His side led by two points, and a goal, especially one by Ring, would surely have inspired a Cork victory. Ring would have had his ninth medal. Wexford hurling might not be the beguiling and romanticised entity it is today.In the game's pivotal moment, the ball quickly travelled down the other end where Tom Ryan sent a raking handpass to Nickey Rackard. In a piece of perfect casting, the greatest name in Wexford hurling landed the deathblow, netting with a low shot to the corner. Wexford were already champions, having defeated Galway in the final a year before to end a 45-year wait. But to beat Cork gave them a status they'd never attained before and wrote them into everlasting legend. The death of Foley at 90 ended a significant chapter for that storied era, he being the last surviving member of the team that won the final in '56 and which started the '55 decider, giving hope to all counties outside the traditional fold. In a decade often depicted as repressive and severe, with heavy emigration, Wexford brought an abundance of novelty and glamour and dauntless expression which made them huge crowd-pullers and popular all over the country. A jazzy addition to the traditional acts. The previous six All-Irelands before Wexford's breakthrough in '55 were shared between Cork and Tipperary. "Why are all these massive crowds following Wexford?" asks Liam Griffin. "The Wexford support base for hurling grew with the rise of the Wexford teams of the 1950s. There was a romantic connection between them and all hurling people. Why? Because they came up to challenge the dominant counties." At the time Wexford looked more likely to prosper in football than hurling. The 1950s, led by the Rackards, changed all that. Only a few survivors remain from the '56 panel: Ted Morrissey, Oliver Gough and Pat Nolan. Morrissey played in the Leinster final before losing his place and had also been on the squad in '51 when Wexford reached the All-Ireland final. Nolan was Art Foley's goalkeeping deputy in '56, later winning All-Ireland medals over a long career in '60 and '68. Gough came on in the '55 final. In a way the loop that began the most famous end-to-end move in Wexford hurling history, starting with Foley's save and concluding with Rackard's goal, was replicated in life itself. The first of that celebrated '56 team to die was Rackard, in April, 1976, at the age of 54 after succumbing to cancer. When the team was celebrating its silver jubilee in 1981, Foley came home from the US for the occasion, having emigrated with his wife Anne and their three young children at 27 in the late 1950s. By the time of the silver jubilee of the '56 win, only Rackard was missing. Gradually over the years the numbers diminished. Ned Wheeler went this year. Billy Rackard was the last of that famous band of brothers to die ten years ago. Now, Foley, literally the last one standing, has gone too. The deeds, though, remain timeless and immortal. The save which made Foley famous followed him around all his days. "The big story of Art Foley is that save because it is the seminal moment of that time," as Liam Griffin puts it. It is also probably the most enigmatic save in the history of the game - the Mona Lisa of hurling saves, such has been the variety of interpretations. Even Ring seems to have offered contradictory accounts. Raymond Smith has an account from John Keane, the former Waterford great, who was umpiring that day. He recalled Ring shooting from 25 yards and the ball moving "so fast that the thought flashed through my mind, this must be a goal . . . and I couldn't believe my eyes when I saw that he'd saved it." One newspaper referred to "a powerful close-in shot" and another to a "piledriver" which was one of "several miracle saves" made by Foley on the day. Val Dorgan, Ring's biographer, reported a "vicious strike" that was saved just under the cross bar and he also used the word "miraculous".It wasn't until the next decade that All-Ireland finals began to be televised, leaving iconic moments like this shrouded in some mystery. Speaking to the Irish Echo in 2011, Foley himself gave this account: "Well, he shot and I blocked it straight up in the air. This is where they always get it wrong. They always say I caught it and cleared it, straight to Nickey [Rackard] and he scored the goal. But I blocked it out and Pat Barry [Cork] doubled on it, and it hit the outside of the net. "I pucked it out to Jim English and he passed it to Tom Ryan, and he got it to Nickey and Nickey got the goal, and we went on to win." It was in keeping with Foley's personality to play down the save's merits. In an interview in 2014, Ned Wheeler referred to Foley as "a gentlemen of few words". They stayed in touch regularly on the phone up to shortly before Wheeler's death. Ted Morrissey was another in frequent contact, a player who moved to Enniscorthy to work and joined the St Aidan's club which Foley played for. "I used to ring him every couple of weeks until recently," says Morrissey, now 89. "I rang him recently and he had fallen, the wife told me he was in the nursing home. "He was very clear, he had a great memory, could tell me all the people who lived on the street where he was. He worked as a lorry driver, that's what he was doing before he left. I suppose he thought there was a better life over there." What did they talk about? "About hurling and old times and the people he knew and he'd be asking me about the people around Enniscorthy. Unfortunately, by the last few conversations there weren't many left that he knew." Foley was just 5'6" at a time when there were marauding full-forwards aplenty and the goalkeeper didn't have the protection in the rulebook he has now. He was dropped after conceding six goals in the 1951 National League final and didn't play in the All-Ireland final later that year against Tipperary when Wexford suffered a heavy loss. Wexford opted for a novice 'keeper, something Billy Rackard later said had been a mistake. When he made the save in '56 Foley was given an appreciative and sporting hand-shake from Ring. The Cloyne man was notoriously competitive but often commented on the sportsmanship of Wexford and specifically his marker Bobby Rackard. At the end of the '56 final Nick O'Donnell and Rackard chaired Ring off the field which is another lasting and remarkable feature of that final. Foley spoke of that moment to Ted Morrissey. "Nicko (O'Donnell) came to Arty and says, 'we'll shoulder him off the field'. And Arty says to him, 'how the hell will we do that, you are 6'2 and I am 5'6 . . . go and get Bobby with you'. So Nicko and Bobby shouldered him off and Arty was a back-up man, giving them a push from behind." Ring stated after the '54 final when Cork defeated Wexford that Cork had never defeated a cleaner team. Perhaps the very different experience he had against Galway in the previous year's final had something to do with that, but the relationship between the counties at the time was cordial and warm. Ring being chaired off the field was its Olympian moment. At a time when hurling was notoriously rough and macho, these displays of sportsmanship were notably different from the norm. It deepened Wexford's unique appeal. Tony Dempsey, the former Wexford county chairman, and former senior hurling manger, met Foley and his wife and some of the family over lunch in Long Island a few years ago, where they made a presentation to him for his services to the county. They spoke of that decision to carry off Ring. "He told me Bobby caught Ring like a doll and lifted him up," said Dempsey, noting the power for which he was renowned. Foley survived in spite of his height limitations, helped by having O'Donnell in front of him. He left school at 13, like many others who were obliged to at the time, and followed his father Tommy, a truck driver, into employment at Davis's Mills in Enniscorthy. He told Dempsey in New York how he routinely carried 12-stone bags of flour up and down ladders at 14. "He took out a photo album and showed a photo of himself jumping for the ball," says Dempsey, "and proportionate to his body he had massive muscles, massive quads and massive thighs." In New York he ended up in long-term employment for TWA, spending 34 years as a crew chief. He came home occasionally, sometimes for reunions. After winning the '56 final, and entering legend, Wexford's victorious players began the triumphant journey home on the Monday night, stopping off in the Market Square in Enniscorthy. A Mr Browne from the county board introduced the players individually. "The greatest ovation was reserved for the goalkeeper Arty Foley whose brilliance in the net contributed much to Wexford's victory," the Irish Independent reported. Forty three years after they laid Nickey Rackard to rest in Bunclody, the first of that special team, Art Foley has gone to his eternal resting place in New York. Their deaths took place decades and thousands of miles apart. But their spirits will remain inseparable.Later, Ring claimed in conversations with Dorgan that he was off balance after being impeded by Paddy Barry and didn't get sufficient power in the shot. Yet Ring himself is quoted in The Irish Press after the match as follows: "It was one of the best saves I ever saw. I thought it was all over when I went through."

26cm x 33cm Ferns Co Wexford An anxious looking Wexford defence prepare as Christy Ring takes a in the 1956 All Ireland Hurling Final.The result would be forever known simply as " The Save ". Art Foley, who died on Monday last in New York, will be remembered for a save he made in the closing stages of the 1956 All-Ireland hurling final that had seismic and far-reaching consequences. It formed an instrumental part of a metamorphic sequence of play in a terrific contest with Cork, leading to one of the game's most epic finales. With three minutes left the ever-threatening Christy Ring gained possession and made for the Wexford goal. The finer points of what happened next are still in dispute. The main thread of the narrative is not. Ring let fly and the diminutive Foley in Wexford's goal was equal to it. He needed to be. His side led by two points, and a goal, especially one by Ring, would surely have inspired a Cork victory. Ring would have had his ninth medal. Wexford hurling might not be the beguiling and romanticised entity it is today.In the game's pivotal moment, the ball quickly travelled down the other end where Tom Ryan sent a raking handpass to Nickey Rackard. In a piece of perfect casting, the greatest name in Wexford hurling landed the deathblow, netting with a low shot to the corner. Wexford were already champions, having defeated Galway in the final a year before to end a 45-year wait. But to beat Cork gave them a status they'd never attained before and wrote them into everlasting legend. The death of Foley at 90 ended a significant chapter for that storied era, he being the last surviving member of the team that won the final in '56 and which started the '55 decider, giving hope to all counties outside the traditional fold. In a decade often depicted as repressive and severe, with heavy emigration, Wexford brought an abundance of novelty and glamour and dauntless expression which made them huge crowd-pullers and popular all over the country. A jazzy addition to the traditional acts. The previous six All-Irelands before Wexford's breakthrough in '55 were shared between Cork and Tipperary. "Why are all these massive crowds following Wexford?" asks Liam Griffin. "The Wexford support base for hurling grew with the rise of the Wexford teams of the 1950s. There was a romantic connection between them and all hurling people. Why? Because they came up to challenge the dominant counties." At the time Wexford looked more likely to prosper in football than hurling. The 1950s, led by the Rackards, changed all that. Only a few survivors remain from the '56 panel: Ted Morrissey, Oliver Gough and Pat Nolan. Morrissey played in the Leinster final before losing his place and had also been on the squad in '51 when Wexford reached the All-Ireland final. Nolan was Art Foley's goalkeeping deputy in '56, later winning All-Ireland medals over a long career in '60 and '68. Gough came on in the '55 final. In a way the loop that began the most famous end-to-end move in Wexford hurling history, starting with Foley's save and concluding with Rackard's goal, was replicated in life itself. The first of that celebrated '56 team to die was Rackard, in April, 1976, at the age of 54 after succumbing to cancer. When the team was celebrating its silver jubilee in 1981, Foley came home from the US for the occasion, having emigrated with his wife Anne and their three young children at 27 in the late 1950s. By the time of the silver jubilee of the '56 win, only Rackard was missing. Gradually over the years the numbers diminished. Ned Wheeler went this year. Billy Rackard was the last of that famous band of brothers to die ten years ago. Now, Foley, literally the last one standing, has gone too. The deeds, though, remain timeless and immortal. The save which made Foley famous followed him around all his days. "The big story of Art Foley is that save because it is the seminal moment of that time," as Liam Griffin puts it. It is also probably the most enigmatic save in the history of the game - the Mona Lisa of hurling saves, such has been the variety of interpretations. Even Ring seems to have offered contradictory accounts. Raymond Smith has an account from John Keane, the former Waterford great, who was umpiring that day. He recalled Ring shooting from 25 yards and the ball moving "so fast that the thought flashed through my mind, this must be a goal . . . and I couldn't believe my eyes when I saw that he'd saved it." One newspaper referred to "a powerful close-in shot" and another to a "piledriver" which was one of "several miracle saves" made by Foley on the day. Val Dorgan, Ring's biographer, reported a "vicious strike" that was saved just under the cross bar and he also used the word "miraculous".It wasn't until the next decade that All-Ireland finals began to be televised, leaving iconic moments like this shrouded in some mystery. Speaking to the Irish Echo in 2011, Foley himself gave this account: "Well, he shot and I blocked it straight up in the air. This is where they always get it wrong. They always say I caught it and cleared it, straight to Nickey [Rackard] and he scored the goal. But I blocked it out and Pat Barry [Cork] doubled on it, and it hit the outside of the net. "I pucked it out to Jim English and he passed it to Tom Ryan, and he got it to Nickey and Nickey got the goal, and we went on to win." It was in keeping with Foley's personality to play down the save's merits. In an interview in 2014, Ned Wheeler referred to Foley as "a gentlemen of few words". They stayed in touch regularly on the phone up to shortly before Wheeler's death. Ted Morrissey was another in frequent contact, a player who moved to Enniscorthy to work and joined the St Aidan's club which Foley played for. "I used to ring him every couple of weeks until recently," says Morrissey, now 89. "I rang him recently and he had fallen, the wife told me he was in the nursing home. "He was very clear, he had a great memory, could tell me all the people who lived on the street where he was. He worked as a lorry driver, that's what he was doing before he left. I suppose he thought there was a better life over there." What did they talk about? "About hurling and old times and the people he knew and he'd be asking me about the people around Enniscorthy. Unfortunately, by the last few conversations there weren't many left that he knew." Foley was just 5'6" at a time when there were marauding full-forwards aplenty and the goalkeeper didn't have the protection in the rulebook he has now. He was dropped after conceding six goals in the 1951 National League final and didn't play in the All-Ireland final later that year against Tipperary when Wexford suffered a heavy loss. Wexford opted for a novice 'keeper, something Billy Rackard later said had been a mistake. When he made the save in '56 Foley was given an appreciative and sporting hand-shake from Ring. The Cloyne man was notoriously competitive but often commented on the sportsmanship of Wexford and specifically his marker Bobby Rackard. At the end of the '56 final Nick O'Donnell and Rackard chaired Ring off the field which is another lasting and remarkable feature of that final. Foley spoke of that moment to Ted Morrissey. "Nicko (O'Donnell) came to Arty and says, 'we'll shoulder him off the field'. And Arty says to him, 'how the hell will we do that, you are 6'2 and I am 5'6 . . . go and get Bobby with you'. So Nicko and Bobby shouldered him off and Arty was a back-up man, giving them a push from behind." Ring stated after the '54 final when Cork defeated Wexford that Cork had never defeated a cleaner team. Perhaps the very different experience he had against Galway in the previous year's final had something to do with that, but the relationship between the counties at the time was cordial and warm. Ring being chaired off the field was its Olympian moment. At a time when hurling was notoriously rough and macho, these displays of sportsmanship were notably different from the norm. It deepened Wexford's unique appeal. Tony Dempsey, the former Wexford county chairman, and former senior hurling manger, met Foley and his wife and some of the family over lunch in Long Island a few years ago, where they made a presentation to him for his services to the county. They spoke of that decision to carry off Ring. "He told me Bobby caught Ring like a doll and lifted him up," said Dempsey, noting the power for which he was renowned. Foley survived in spite of his height limitations, helped by having O'Donnell in front of him. He left school at 13, like many others who were obliged to at the time, and followed his father Tommy, a truck driver, into employment at Davis's Mills in Enniscorthy. He told Dempsey in New York how he routinely carried 12-stone bags of flour up and down ladders at 14. "He took out a photo album and showed a photo of himself jumping for the ball," says Dempsey, "and proportionate to his body he had massive muscles, massive quads and massive thighs." In New York he ended up in long-term employment for TWA, spending 34 years as a crew chief. He came home occasionally, sometimes for reunions. After winning the '56 final, and entering legend, Wexford's victorious players began the triumphant journey home on the Monday night, stopping off in the Market Square in Enniscorthy. A Mr Browne from the county board introduced the players individually. "The greatest ovation was reserved for the goalkeeper Arty Foley whose brilliance in the net contributed much to Wexford's victory," the Irish Independent reported. Forty three years after they laid Nickey Rackard to rest in Bunclody, the first of that special team, Art Foley has gone to his eternal resting place in New York. Their deaths took place decades and thousands of miles apart. But their spirits will remain inseparable.Later, Ring claimed in conversations with Dorgan that he was off balance after being impeded by Paddy Barry and didn't get sufficient power in the shot. Yet Ring himself is quoted in The Irish Press after the match as follows: "It was one of the best saves I ever saw. I thought it was all over when I went through." -

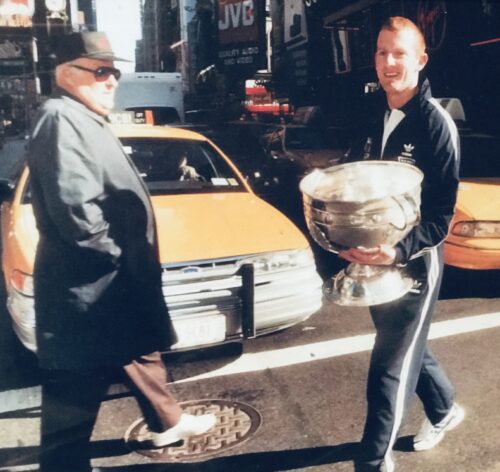

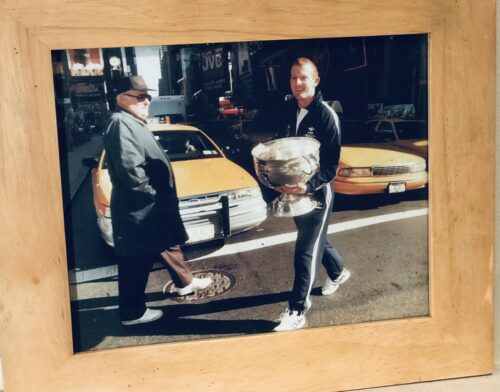

29cm x 34cm. New York The enormous prize that is Sam Maguire proudly paraded across a Manhattan street by Kerry Captain Liam Hassett during a post All Ireland visit to the city that never sleeps in 1997.A semi nterested New Yorker looks on whilst the 'big yellow taxis' add to the atmosphere in this superb photograph that links the countries of Ireland and its big cousin in the United States. The Sam Maguire Cup, often referred to as Sam or The Sam (Irish: Corn Sam Mhic Uidhir), is a trophy awarded annually by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) to the team that wins the All-Ireland Senior Football Championship, the main competition in the medieval sport of Gaelic football. The Sam Maguire Cup was first presented to the winners of the 1928 All-Ireland Senior Football Championship Final. The original 1920s trophy was retired in the 1980s, with a new identical trophy awarded annually since 1988. The GAA organises the series of games, which are played during the summer months. The All-Ireland Football Final was traditionally played on the third or fourth Sunday in September at Croke Park in Dublin. In 2018, the GAA rescheduled its calendar and since then the fixture has been played in early September

29cm x 34cm. New York The enormous prize that is Sam Maguire proudly paraded across a Manhattan street by Kerry Captain Liam Hassett during a post All Ireland visit to the city that never sleeps in 1997.A semi nterested New Yorker looks on whilst the 'big yellow taxis' add to the atmosphere in this superb photograph that links the countries of Ireland and its big cousin in the United States. The Sam Maguire Cup, often referred to as Sam or The Sam (Irish: Corn Sam Mhic Uidhir), is a trophy awarded annually by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) to the team that wins the All-Ireland Senior Football Championship, the main competition in the medieval sport of Gaelic football. The Sam Maguire Cup was first presented to the winners of the 1928 All-Ireland Senior Football Championship Final. The original 1920s trophy was retired in the 1980s, with a new identical trophy awarded annually since 1988. The GAA organises the series of games, which are played during the summer months. The All-Ireland Football Final was traditionally played on the third or fourth Sunday in September at Croke Park in Dublin. In 2018, the GAA rescheduled its calendar and since then the fixture has been played in early SeptemberOld trophy

The original Sam Maguire Cup commemorates the memory of Sam Maguire, an influential figure in the London GAA and a former footballer. A group of his friends formed a committee in Dublin under the chairmanship of Dr Pat McCartan from Carrickmore, County Tyrone, to raise funds for a permanent commemoration of his name. They decided on a cup to be presented to the GAA. The Association were proud to accept the Cup. At the time it cost £300. In today's terms that sum is equivalent to €25,392. The commission to make it was given to Hopkins and Hopkins, a jewellers and watchmakers of O'Connell Bridge, Dublin. The silver cup was crafted, on behalf of Hopkins and Hopkins, by the silversmith Matthew J. Staunton of D'Olier Street, Dublin. Maitiú Standun, Staunton's son, confirmed in a letter printed in the Alive! newspaper in October 2003 that his father had indeed made the original Sam Maguire Cup back in 1928. Matthew J. Staunton (1888–1966) came from a long line of silversmiths going back to the Huguenots, who brought their skills to Ireland in the 1600s. Matt, as he was known to his friends, served his time in the renowned Dublin silversmiths, Edmond Johnson Ltd, where the Liam MacCarthy Hurling Cup was made in 1921. The 1928 Sam Maguire Cup is a faithful model of the Ardagh Chalice. The bowl was not spun on a spinning lathe but hand-beaten from a single flat piece of silver. Even though it is highly polished, multiple hammer marks are still visible today, indicating the manufacturing process. It was first presented in 1928 - to the Kildare team that defeated Cavan by one point in that year's final. It was the only time Kildare won old trophy. They have yet to win the new trophy, coming closest in 1998, when Galway defeated them by four points in that year's final. Kerry won the trophy on the most occasions. They were also the only team to win it on four consecutive occasions, achieving the feat twice -first during the late-1920s and early-1930s (1929, 1930, 1931, 1932), and later during the late-1970s and early 1980s (1978, 1979, 1980, 1981). In addition, Kerry twice won the old trophy on three consecutive occasions, in the late 1930s and early-1940s (1939, 1940, 1941) and in the mid-1980s (1984, 1985, 1986). They also won it on two consecutive occasions in the late-1960s and early-1970s (1969, 1970). Galway won the old trophy on three consecutive occasions in the mid-1960s (1964, 1965, 1966). Roscommon won the old trophy on two consecutive occasions during the mid-1940s (1943, 1944), as did Cavan later that decade (1947, 1948). Mayo won the old trophy on two consecutive occasions during the early-1950s (1950, 1951), while Down did likewise in the early-1960s (1960, 1961). Offaly won the old trophy on two consecutive occasions during the early 1970s (1971, 1972), while Dublin did likewise later that decade (1976, 1977). Six men won the old trophy twice as captain: Joe Barrett of Kerry, Jimmy Murray of Roscommon, John Joe O'Reilly of Cavan, Seán Flanagan of Mayo, Enda Colleran of Galway and Tony Hanahoeof Dublin. The original trophy was retired in 1988 as it had received some damage over the years. It is permanently on display in the GAA Museum at Croke Park. Original 1928 Sam Maguire Cup on display in the GAA Museum at Croke Park

Original 1928 Sam Maguire Cup on display in the GAA Museum at Croke ParkNew trophy

The GAA commissioned a replica from Kilkenny-based silversmith Desmond A. Byrne and the replica is the trophy that has been used ever since. The silver for the new cup was donated by Johnson Matthey Ireland at the behest of Kieran D. Eustace Managing Director, a native of Newtowncashel Co. Longford . Meath's Joe Cassells was the first recipient of "Sam Óg". Meath have the distinction of being the last team to lift the old Sam Maguire and the first team to lift the new one following their back-to-back victories in 1987 and 1988. Cork won the new trophy on consecutive occasions in the late-1980s and early-1990s (1989, 1990), while Kerry did likewise during the mid-2000s (2006, 2007). Dublin are the only team to win the new trophy on more than two consecutive occasions, achieving a historic achievement of five-in-a-row during the second half of the 2010s (2015, 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019). Stephen Cluxton of Dublin is the only captain to have won the new trophy six times as captain, doing so in 2013, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019. No other person as ever won either the old or new trophy as captain more than twice. Two other men have won the new trophy twice as captain: Declan O'Sullivan of Kerry and Brian Dooher of Tyrone. In 2010, the GAA asked the same silversmith to produce another replica of the trophy (the third Sam Maguire Cup) although this was to be used only for marketing purposes.Winners

Old Trophy- Kerry – 1929, 1930, 1931, 1932, 1937, 1939, 1940, 1941, 1946, 1953, 1955, 1959, 1962, 1969, 1970, 1975, 1978, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1984, 1985, 1986

- Dublin – 1942, 1958, 1963, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1983

- Galway – 1934, 1938, 1956, 1964, 1965, 1966

- Cavan – 1933, 1935, 1947, 1948, 1952

- Meath – 1949, 1954, 1967, 1987

- Mayo – 1936, 1950, 1951

- Down – 1960, 1961, 1968

- Offaly – 1971, 1972, 1982

- Roscommon – 1943, 1944

- Cork – 1945, 1973

- Kildare – 1928

- Louth – 1957

-

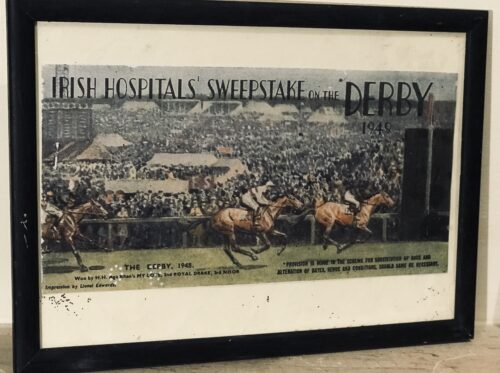

Enlarged ,framed ticket stub for the 1949 Irish Hospital Sweepstake for the Epsom Derby. Dublin 23cm x 31cm The Irish Hospital Sweepstake was a lottery established in the Irish Free State in 1930 as the Irish Free State Hospitals' Sweepstake to finance hospitals. It is generally referred to as the Irish Sweepstake, frequently abbreviated to Irish Sweeps or Irish Sweep. The Public Charitable Hospitals (Temporary Provisions) Act, 1930 was the act that established the lottery; as this act expired in 1934, in accordance with its terms, the Public Hospitals Acts were the legislative basis for the scheme thereafter. The main organisers were Richard Duggan, Captain Spencer Freeman and Joe McGrath. Duggan was a well known Dublin bookmaker who had organised a number of sweepstakes in the decade prior to setting up the Hospitals' Sweepstake. Captain Freeman was a Welsh-born engineer and former captain in the British Army. After the Constitution of Ireland was enacted in 1937, the name Irish Hospitals' Sweepstake was adopted. The sweepstake was established because there was a need for investment in hospitals and medical services and the public finances were unable to meet this expense at the time. As the people of Ireland were unable to raise sufficient funds, because of the low population, a significant amount of the funds were raised in the United Kingdom and United States, often among the emigrant Irish. Potentially winning tickets were drawn from rotating drums, usually by nurses in uniform. Each such ticket was assigned to a horse expected to run in one of several horse races, including the Cambridgeshire Handicap, Derby and Grand National. Tickets that drew the favourite horses thus stood a higher likelihood of winning and a series of winning horses had to be chosen on the accumulator system, allowing for enormous prizes. The original sweepstake draws were held at The Mansion House, Dublin on 19 May 1939 under the supervision of the Chief Commissioner of Police, and were moved to the more permanent fixture at the Royal Dublin Society (RDS) in Ballsbridge later in 1940. The Adelaide Hospital in Dublin was the only hospital at the time not to accept money from the Hospitals Trust, as the governors disapproved of sweepstakes. From the 1960s onwards, revenues declined. The offices were moved to Lotamore House in Cork. Although giving the appearance of a public charitable lottery, with nurses featured prominently in the advertising and drawings, the Sweepstake was in fact a private for-profit lottery company, and the owners were paid substantial dividends from the profits. Fortune Magazine described it as "a private company run for profit and its handful of stockholders have used their earnings from the sweepstakes to build a group of industrial enterprises that loom quite large in the modest Irish economy. Waterford Glass, Irish Glass Bottle Company and many other new Irish companies were financed by money from this enterprise and up to 5,000 people were given jobs."[3] By his death in 1966, Joe McGrath had interests in the racing industry, and held the Renault dealership for Ireland besides large financial and property assets. He was known throughout Ireland for his tough business attitude but also by his generous spirit.At that time, Ireland was still one of the poorer countries in Europe; he believed in investment in Ireland. His home, Cabinteely House, was donated to the state in 1986. The house and the surrounding park are now in the ownership of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council who have invested in restoring and maintaining the house and grounds as a public park. In 1986, the Irish government created a new public lottery, and the company failed to secure the new contract to manage it. The final sweepstake was held in January 1986 and the company was unsuccessful for a licence bid for the Irish National Lottery, which was won by An Post later that year. The company went into voluntary liquidation in March 1987. The majority of workers did not have a pension scheme but the sweepstake had fed many families during lean times and was regarded as a safe job.The Public Hospitals (Amendment) Act, 1990 was enacted for the orderly winding up of the scheme which had by then almost £500,000 in unclaimed prizes and accrued interest. A collection of advertising material relating to the Irish Hospitals' Sweepstakes is among the Special Collections of National Irish Visual Arts Library. At the time of the Sweepstake's inception, lotteries were generally illegal in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. In the absence of other readily available lotteries, the Irish Sweeps became popular. Even though tickets were illegal outside Ireland, millions were sold in the US and Great Britain. How many of these tickets failed to make it back for the drawing is unknown. The United States Customs Service alone confiscated and destroyed several million counterfoils from shipments being returned to Ireland. In the UK, the sweepstakes caused some strain in Anglo-Irish relations, and the Betting and Lotteries Act 1934 was passed by the parliament of the UK to prevent export and import of lottery related materials. The United States Congress had outlawed the use of the US Postal Service for lottery purposes in 1890. A thriving black market sprang up for tickets in both jurisdictions. From the 1950s onwards, as the American, British and Canadian governments relaxed their attitudes towards this form of gambling, and went into the lottery business themselves, the Irish Sweeps, never legal in the United States,declined in popularity. Origins: Co Galway Dimensions :39cm x 31cm

Enlarged ,framed ticket stub for the 1949 Irish Hospital Sweepstake for the Epsom Derby. Dublin 23cm x 31cm The Irish Hospital Sweepstake was a lottery established in the Irish Free State in 1930 as the Irish Free State Hospitals' Sweepstake to finance hospitals. It is generally referred to as the Irish Sweepstake, frequently abbreviated to Irish Sweeps or Irish Sweep. The Public Charitable Hospitals (Temporary Provisions) Act, 1930 was the act that established the lottery; as this act expired in 1934, in accordance with its terms, the Public Hospitals Acts were the legislative basis for the scheme thereafter. The main organisers were Richard Duggan, Captain Spencer Freeman and Joe McGrath. Duggan was a well known Dublin bookmaker who had organised a number of sweepstakes in the decade prior to setting up the Hospitals' Sweepstake. Captain Freeman was a Welsh-born engineer and former captain in the British Army. After the Constitution of Ireland was enacted in 1937, the name Irish Hospitals' Sweepstake was adopted. The sweepstake was established because there was a need for investment in hospitals and medical services and the public finances were unable to meet this expense at the time. As the people of Ireland were unable to raise sufficient funds, because of the low population, a significant amount of the funds were raised in the United Kingdom and United States, often among the emigrant Irish. Potentially winning tickets were drawn from rotating drums, usually by nurses in uniform. Each such ticket was assigned to a horse expected to run in one of several horse races, including the Cambridgeshire Handicap, Derby and Grand National. Tickets that drew the favourite horses thus stood a higher likelihood of winning and a series of winning horses had to be chosen on the accumulator system, allowing for enormous prizes. The original sweepstake draws were held at The Mansion House, Dublin on 19 May 1939 under the supervision of the Chief Commissioner of Police, and were moved to the more permanent fixture at the Royal Dublin Society (RDS) in Ballsbridge later in 1940. The Adelaide Hospital in Dublin was the only hospital at the time not to accept money from the Hospitals Trust, as the governors disapproved of sweepstakes. From the 1960s onwards, revenues declined. The offices were moved to Lotamore House in Cork. Although giving the appearance of a public charitable lottery, with nurses featured prominently in the advertising and drawings, the Sweepstake was in fact a private for-profit lottery company, and the owners were paid substantial dividends from the profits. Fortune Magazine described it as "a private company run for profit and its handful of stockholders have used their earnings from the sweepstakes to build a group of industrial enterprises that loom quite large in the modest Irish economy. Waterford Glass, Irish Glass Bottle Company and many other new Irish companies were financed by money from this enterprise and up to 5,000 people were given jobs."[3] By his death in 1966, Joe McGrath had interests in the racing industry, and held the Renault dealership for Ireland besides large financial and property assets. He was known throughout Ireland for his tough business attitude but also by his generous spirit.At that time, Ireland was still one of the poorer countries in Europe; he believed in investment in Ireland. His home, Cabinteely House, was donated to the state in 1986. The house and the surrounding park are now in the ownership of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council who have invested in restoring and maintaining the house and grounds as a public park. In 1986, the Irish government created a new public lottery, and the company failed to secure the new contract to manage it. The final sweepstake was held in January 1986 and the company was unsuccessful for a licence bid for the Irish National Lottery, which was won by An Post later that year. The company went into voluntary liquidation in March 1987. The majority of workers did not have a pension scheme but the sweepstake had fed many families during lean times and was regarded as a safe job.The Public Hospitals (Amendment) Act, 1990 was enacted for the orderly winding up of the scheme which had by then almost £500,000 in unclaimed prizes and accrued interest. A collection of advertising material relating to the Irish Hospitals' Sweepstakes is among the Special Collections of National Irish Visual Arts Library. At the time of the Sweepstake's inception, lotteries were generally illegal in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. In the absence of other readily available lotteries, the Irish Sweeps became popular. Even though tickets were illegal outside Ireland, millions were sold in the US and Great Britain. How many of these tickets failed to make it back for the drawing is unknown. The United States Customs Service alone confiscated and destroyed several million counterfoils from shipments being returned to Ireland. In the UK, the sweepstakes caused some strain in Anglo-Irish relations, and the Betting and Lotteries Act 1934 was passed by the parliament of the UK to prevent export and import of lottery related materials. The United States Congress had outlawed the use of the US Postal Service for lottery purposes in 1890. A thriving black market sprang up for tickets in both jurisdictions. From the 1950s onwards, as the American, British and Canadian governments relaxed their attitudes towards this form of gambling, and went into the lottery business themselves, the Irish Sweeps, never legal in the United States,declined in popularity. Origins: Co Galway Dimensions :39cm x 31cmThe Irish Hospitals Sweepstake was established because there was a need for investment in hospitals and medical services and the public finances were unable to meet this expense at the time. As the people of Ireland were unable to raise sufficient funds, because of the low population, a significant amount of the funds were raised in the United Kingdom and United States, often among the emigrant Irish. Potentially winning tickets were drawn from rotating drums, usually by nurses in uniform. Each such ticket was assigned to a horse expected to run in one of several horse races, including the Cambridgeshire Handicap, Derby and Grand National. Tickets that drew the favourite horses thus stood a higher likelihood of winning and a series of winning horses had to be chosen on the accumulator system, allowing for enormous prizes.

The original sweepstake draws were held at The Mansion House, Dublin on 19 May 1939 under the supervision of the Chief Commissioner of Police, and were moved to the more permanent fixture at the Royal Dublin Society (RDS) in Ballsbridge later in 1940. The Adelaide Hospital in Dublin was the only hospital at the time not to accept money from the Hospitals Trust, as the governors disapproved of sweepstakes. From the 1960s onwards, revenues declined. The offices were moved to Lotamore House in Cork. Although giving the appearance of a public charitable lottery, with nurses featured prominently in the advertising and drawings, the Sweepstake was in fact a private for-profit lottery company, and the owners were paid substantial dividends from the profits. Fortune Magazine described it as "a private company run for profit and its handful of stockholders have used their earnings from the sweepstakes to build a group of industrial enterprises that loom quite large in the modest Irish economy. Waterford Glass, Irish Glass Bottle Company and many other new Irish companies were financed by money from this enterprise and up to 5,000 people were given jobs."By his death in 1966, Joe McGrath had interests in the racing industry, and held the Renault dealership for Ireland besides large financial and property assets. He was known throughout Ireland for his tough business attitude but also by his generous spirit. At that time, Ireland was still one of the poorer countries in Europe; he believed in investment in Ireland. His home, Cabinteely House, was donated to the state in 1986. The house and the surrounding park are now in the ownership of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council who have invested in restoring and maintaining the house and grounds as a public park. In 1986, the Irish government created a new public lottery, and the company failed to secure the new contract to manage it. The final sweepstake was held in January 1986 and the company was unsuccessful for a licence bid for the Irish National Lottery, which was won by An Post later that year. The company went into voluntary liquidation in March 1987. The majority of workers did not have a pension scheme but the sweepstake had fed many families during lean times and was regarded as a safe job.The Public Hospitals (Amendment) Act, 1990 was enacted for the orderly winding up of the scheme,which had by then almost £500,000 in unclaimed prizes and accrued interest. A collection of advertising material relating to the Irish Hospitals' Sweepstakes is among the Special Collections of National Irish Visual Arts Library.In the United Kingdom and North America[edit]

At the time of the Sweepstake's inception, lotteries were generally illegal in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. In the absence of other readily available lotteries, the Irish Sweeps became popular. Even though tickets were illegal outside Ireland, millions were sold in the US and Great Britain. How many of these tickets failed to make it back for the drawing is unknown. The United States Customs Service alone confiscated and destroyed several million counterfoils from shipments being returned to Ireland. In the UK, the sweepstakes caused some strain in Anglo-Irish relations, and the Betting and Lotteries Act 1934 was passed by the parliament of the UK to prevent export and import of lottery related materials.[6][7] The United States Congress had outlawed the use of the US Postal Service for lottery purposes in 1890. A thriving black market sprang up for tickets in both jurisdictions. From the 1950s onwards, as the American, British and Canadian governments relaxed their attitudes towards this form of gambling, and went into the lottery business themselves, the Irish Sweeps, never legal in the United States,[8]:227 declined in popularity. -

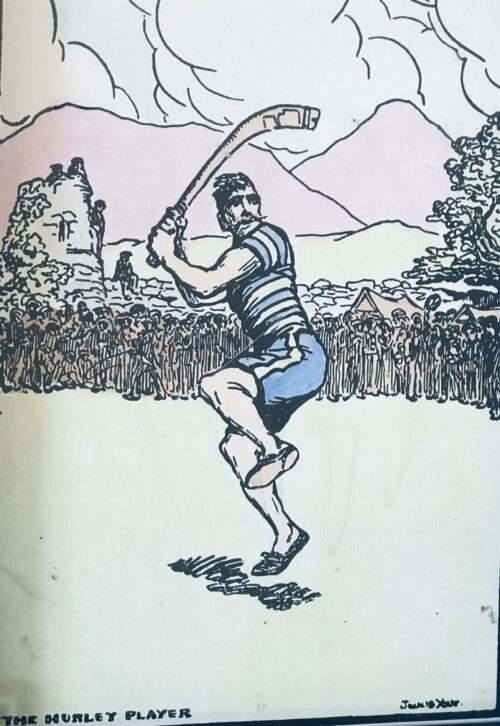

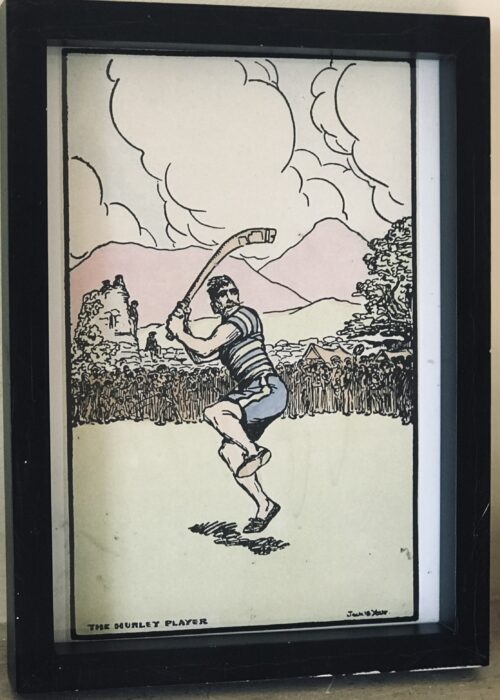

The Hurley Playerby Jack B Yeats in nice, offset frame. 33cm x 24cm Jack Butler Yeats RHA (29 August 1871 – 28 March 1957) was an Irish artist and Olympic medalist. W. B. Yeats was his brother. Butler's early style was that of an illustrator; he only began to work regularly in oils in 1906. His early pictures are simple lyrical depictions of landscapes and figures, predominantly from the west of Ireland—especially of his boyhood home of Sligo. Yeats's work contains elements of Romanticism. He later would adopt the style of Expressionism

The Hurley Playerby Jack B Yeats in nice, offset frame. 33cm x 24cm Jack Butler Yeats RHA (29 August 1871 – 28 March 1957) was an Irish artist and Olympic medalist. W. B. Yeats was his brother. Butler's early style was that of an illustrator; he only began to work regularly in oils in 1906. His early pictures are simple lyrical depictions of landscapes and figures, predominantly from the west of Ireland—especially of his boyhood home of Sligo. Yeats's work contains elements of Romanticism. He later would adopt the style of ExpressionismBiography

Yeats was born in London, England. He was the youngest son of Irish portraitist John Butler Yeats and the brother of W. B. Yeats, who received the 1923 Nobel Prize in Literature. He grew up in Sligo with his maternal grandparents, before returning to his parents' home in London in 1887. Early in his career he worked as an illustrator for magazines like the Boy's Own Paper and Judy, drew comic strips, including the Sherlock Holmes parody "Chubb-Lock Homes" for Comic Cuts, and wrote articles for Punch under the pseudonym "W. Bird".In 1894 he married Mary Cottenham, also a native of England and two years his senior, and resided in Wicklow according to the Census of Ireland, 1911. From around 1920, he developed into an intensely Expressionist artist, moving from illustration to Symbolism. He was sympathetic to the Irish Republican cause, but not politically active. However, he believed that 'a painter must be part of the land and of the life he paints', and his own artistic development, as a Modernist and Expressionist, helped articulate a modern Dublin of the 20th century, partly by depicting specifically Irish subjects, but also by doing so in the light of universal themes such as the loneliness of the individual, and the universality of the plight of man. Samuel Beckett wrote that "Yeats is with the great of our time... because he brings light, as only the great dare to bring light, to the issueless predicament of existence."The Marxist art critic and author John Berger also paid tribute to Yeats from a very different perspective, praising the artist as a "great painter" with a "sense of the future, an awareness of the possibility of a world other than the one we know". His favourite subjects included the Irish landscape, horses, circus and travelling players. His early paintings and drawings are distinguished by an energetic simplicity of line and colour, his later paintings by an extremely vigorous and experimental treatment of often thickly applied paint. He frequently abandoned the brush altogether, applying paint in a variety of different ways, and was deeply interested in the expressive power of colour. Despite his position as the most important Irish artist of the 20th century (and the first to sell for over £1m), he took no pupils and allowed no one to watch him work, so he remains a unique figure. The artist closest to him in style is his friend, the Austrian painter, Oskar Kokoschka. Besides painting, Yeats had a significant interest in theatre and in literature. He was a close friend of Samuel Beckett. He designed sets for the Abbey Theatre, and three of his own plays were also produced there. He wrote novels in a stream of consciousness style that Joyce acknowledged, and also many essays. His literary works include The Careless Flower, The Amaranthers (much admired by Beckett), Ah Well, A Romance in Perpetuity, And To You Also, and The Charmed Life. Yeats's paintings usually bear poetic and evocative titles. Indeed, his father recognized that Jack was a far better painter than he, and also believed that 'some day I will be remembered as the father of a great poet, and the poet is Jack'.He was elected a member of the Royal Hibernian Academy in 1916.He died in Dublin in 1957, and was buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery. Yeats holds the distinction of being Ireland's first medalist at the Olympic Games in the wake of creation of the Irish Free State. At the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, Yeats' painting The Liffey Swim won a silver medal in the arts and culture segment of the Games. In the competition records the painting is simply entitled Swimming.Works

In November 2010, one of Yeats's works, A Horseman Enters a Town at Night, painted in 1948 and previously owned by novelist Graham Greene, sold for nearly £350,000 at a Christie's auction in London. A smaller work, Man in a Room Thinking, painted in 1947, sold for £66,000 at the same auction. In 1999 the painting, The Wild Ones, had sold at Sotheby's in London for over £1.2m, the highest price yet paid for a Yeats painting. Adam's Auctioneers hold the Irish record sale price for a Yeats painting, A Fair Day, Mayo (1925), which sold for €1,000,000 in September 2011.Hosting museums

- The Hunt Museum, Limerick

- The National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

- The Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin

- Crawford Art Gallery, Cork

- Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin

- The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

- Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

- Model Arts and Niland Gallery, Sligo

- The Municipal Art Collection, Waterford

- Ulster Museum, Belfast

- The Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame

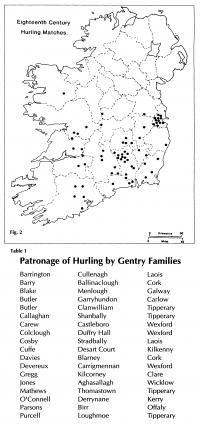

The Geography of Hurling

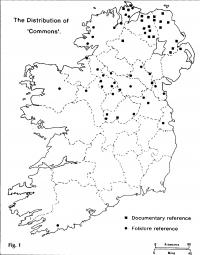

Kevin Whelan Why is hurling currently popular in a compact region centred on east Munster and south Leinster, and in isolated pockets in the Glens of Antrim and in the Ards peninsula of County Down? The answer lies in an exploration of the interplay between culture, politics and environment over a long period of time. TWO VERSIONS By the eighteenth century it is quite clear that there were two principal, and regionally distinct,versions of the game. One was akin to modern field hockey, or shinty, in that it did not allow handling of the ball; it was played with a narrow, crooked stick; it used a hard wooden ball (the ‘crag’); it was mainly a winter game. This game, called camán (anglicised to ‘commons’), was confined to the northern half of the country; its southern limits were set sharply where the small farms of the drumlin belt petered out into the pastoral central lowlands. (Fig 1)

‘The Hurley Player’ by Jack B. Yeats

The second version of the game (iomán or báire) was of southern provenance. The ball could be handled or carried on the hurl, which was flat and round-headed; the ball (the sliothar) was soft and made of animal hair; the game was played in summer. Unlike commons, this form of hurling was patronised by the gentry, as a spectator and gambling sport, associated with fairs and other public gatherings, and involved a much greater degree of organisation (including advertising) than the more demotic ‘commons’. A 1742 advertisement for Ballyspellan Spa in Kilkenny noted that ‘horse racing, dancing and hurling will be provided for the pleasure of the quality at the spa’.

LANDLORD PATRONAGE

A number of factors determined the distribution of the southern game. (Fig. 2) The most important was the patronage of local gentry families, particularly those most closely embedded in the life of the local people. (Table 1) They picked the teams, arranged the hurling greens and supervised the matches, which were frequently organised as gambling events. The southern hurling zone coincides with the area where, in the late medieval period, the Norman and Gaelic worlds fused to produce a vigorous culture, reflected, for example, in the towerhouse as an architectural innovation. It coincides with well-drained, level terrain, seldom moving too far off the dry sod of limestone areas, which also happen to produce the best material for hurls – ash. It is closely linked to the distribution of big farms, where the relatively comfortable lifestyle afforded the leisure to pursue the sport.

Landlord patronage was essential to the well-being of the southern game; once it was removed, the structures it supported crumbled and the game collapsed into shapeless anarchy. The progressive separation of the manners and language of the élite from the common people was a pan-European phenomenon in the modern period. The gentry’s disengagement from immersion in the shared intimacies of daily life can be seen not just in hurling, but in other areas of language, music, sport and behaviour, as the gradual reception of metropolitan ideas eroded the older loyalties. As one hostile observer put it:

A hurling match is a scene of drunkenness, blasphemy and all kinds and manner of debauchery and faith, for my part, I would liken it to nothing else but to the idea I form of the Stygian regions where the daemonic inhabitants delight in torturing and afflicting each other.

DECLINE

By the mid nineteenth century, hurling had declined so steeply that it survived only in three pockets, around Cork city, in south-east Galway and in the area north of Wexford town. Amongst the reasons for decline were the withdrawal of gentry patronage in an age of political turbulence, sabbitudinarianism, modernisation and the dislocating impact of the Famine. Landlord, priest and magistrate all turned against the game. The older ‘moral economy’, which had linked landlord and tenant in bonds of patronage and deference, gave way to a sharper, adversarial relationship, especially in the 1790s, as the impact of the French Revolution in Ireland created a greater class-consciousness. Politicisation led to a growing anti-landlord feeling, which had been far more subdued in the heyday of gentry-sponsored hurling between the 1740s and 1760s.

The second version of the game (iomán or báire) was of southern provenance. The ball could be handled or carried on the hurl, which was flat and round-headed; the ball (the sliothar) was soft and made of animal hair; the game was played in summer. Unlike commons, this form of hurling was patronised by the gentry, as a spectator and gambling sport, associated with fairs and other public gatherings, and involved a much greater degree of organisation (including advertising) than the more demotic ‘commons’. A 1742 advertisement for Ballyspellan Spa in Kilkenny noted that ‘horse racing, dancing and hurling will be provided for the pleasure of the quality at the spa’.

LANDLORD PATRONAGE

A number of factors determined the distribution of the southern game. (Fig. 2) The most important was the patronage of local gentry families, particularly those most closely embedded in the life of the local people. (Table 1) They picked the teams, arranged the hurling greens and supervised the matches, which were frequently organised as gambling events. The southern hurling zone coincides with the area where, in the late medieval period, the Norman and Gaelic worlds fused to produce a vigorous culture, reflected, for example, in the towerhouse as an architectural innovation. It coincides with well-drained, level terrain, seldom moving too far off the dry sod of limestone areas, which also happen to produce the best material for hurls – ash. It is closely linked to the distribution of big farms, where the relatively comfortable lifestyle afforded the leisure to pursue the sport.

Landlord patronage was essential to the well-being of the southern game; once it was removed, the structures it supported crumbled and the game collapsed into shapeless anarchy. The progressive separation of the manners and language of the élite from the common people was a pan-European phenomenon in the modern period. The gentry’s disengagement from immersion in the shared intimacies of daily life can be seen not just in hurling, but in other areas of language, music, sport and behaviour, as the gradual reception of metropolitan ideas eroded the older loyalties. As one hostile observer put it:

A hurling match is a scene of drunkenness, blasphemy and all kinds and manner of debauchery and faith, for my part, I would liken it to nothing else but to the idea I form of the Stygian regions where the daemonic inhabitants delight in torturing and afflicting each other.

DECLINE

By the mid nineteenth century, hurling had declined so steeply that it survived only in three pockets, around Cork city, in south-east Galway and in the area north of Wexford town. Amongst the reasons for decline were the withdrawal of gentry patronage in an age of political turbulence, sabbitudinarianism, modernisation and the dislocating impact of the Famine. Landlord, priest and magistrate all turned against the game. The older ‘moral economy’, which had linked landlord and tenant in bonds of patronage and deference, gave way to a sharper, adversarial relationship, especially in the 1790s, as the impact of the French Revolution in Ireland created a greater class-consciousness. Politicisation led to a growing anti-landlord feeling, which had been far more subdued in the heyday of gentry-sponsored hurling between the 1740s and 1760s.

MICHAEL CUSACK & THE GAA

The model of élite participation in popular culture is a threefold process: first immersion, then withdrawal, and, finally rediscovery, invariably by an educated élite, and often with a nationalist agenda. ‘Rediscovery’ usually involves an invention of tradition, creating a packaged, homogenised and often false version of an idealised popular culture – as, for example, in the cult of the Highland kilt. The relationship of hurling and the newly established Gaelic Athletic Association in the 1880s shows this third phase with textbook clarity. Thus, when Michael Cusack set about reviving the game, he codified a synthetic version, principally modelled on the southern ‘iomán’ version that he had known as a child in Clare. Not surprisingly, this new game never caught on in the old ‘commons’ area, with the Glens of Antrim being the only major exception. Cusack and his GAA backers also wished to use the game as a nationalising idiom, a symbolic language of identity filling the void created by the speed of anglicisation. It had therefore to be sharply fenced off in organisational terms from competing ‘anglicised’ sports like cricket, soccer and rugby. Thus, from the beginning, the revived game had a nationalist veneer, its rules of association bristling like a porcupine with protective nationalist quills on which its perceived opponents would have to impale themselves. Its principal backers were those already active in the nationalist political culture of the time, classically the I.R.B. Its spread depended on the active support of an increasingly nationalist Catholic middle class – and as in every country concerned with the invention of tradition, its social constituency included especially journalists, publicans, schoolteachers, clerks, artisans and clerics. Thus, hurling’s early success was in south Leinster and east Munster, the very region which pioneered popular Irish nationalist politics – from the O’Connell campaign, to the devotional revolution in Irish Catholicism, from Fr. Matthews’ temperance campaign, to the Fenians, to the take-over of local government. The GAA was a classic example of the radical conservatism of this region – conservative in its ethos and ideology, radical in its techniques of organisation and mobilisation. The spread of hurling can be very closely matched to the spread of other radical conservative movements of this period – the diffusion of the indigenous Catholic teaching orders and the spread of co-operative dairying.

It would, however, be a mistake to see the spread of hurling under the aegis of the GAA solely in nationalist terms. The codification and success of gaelic games should be compared to the almost contemporaneous success in Britain of codified versions of soccer and rugby. All these were linked to rising spending power, a shortened working week (and the associated development of the ‘weekend’), improved and cheaper mass transport facilities which made spectator sports viable, expanded leisure time, the desire for organised sport among the working classes, and the commercialisation of leisure itself. The really distinctive feature of the GAA’s success was that it occurred in what was still a predominantly agrarian society. That success rested on the shrewd application of the principle of territoriality.

TERRITORIAL ALLEGIANCE

Irish rural life was essentially local life. Hurling was quintessentially a territorially based game – teams based on communities, parishes, counties, pitted one against the other. The painter Tony O’Malley has contrasted this tribal-territorial element in Irish sport to English attitudes:

If neighbours were playing like New Ross and Tullogher, there would be a real needle in it. When Carrickshock were playing, I once heard an old man shouting ‘come on the men that bate the tithe proctors’ and there was a tremor and real fervour in his voice. It was a battle cry, with hurleys as the swords, but with the same intensity.

Similar forces of territoriality have been identified behind the success of cricket in the West Indies and rugby in the Welsh valleys. The GAA tapped this deep-seated territorial loyalty, of the type which is beautifully captured in the rhetorical climax of the great underground classic of rural Ireland, Knocknagow or the Homes of Tipperary by Charles J. Kickham. Matt Donovan (Matt the Thrasher), the village hero, is competing against the outsider Captain French in a sledge-throwing contest. In the absence of steroids, Matt is pumping himself up before his throw:

Someone struck the big drum a single blow, as if by accident and, turning round quickly, the thatched roofs of the hamlet caught his eye. And, strange to say, those old mud walls and thatched roofs roused him as nothing else could. His breast heaved, as with glistening eyes, and that soft plaintive smile of his, he uttered the words, ‘For the credit of the little village!’ in a tone of the deepest tenderness. Then, grasping the sledge in his right hand, and drawing himself up to his full height, he measured the captain’s cast with his eye. The muscles of his arms seemed to start out like cords of steel as he wheeled slowly round and shot the ponderous hammer through the air. His eyes dilated as, with quivering nostrils, he watched its flight, till it fell so far beyond the best mark that even he himself started with astonishment. Then a shout of exultation burst from the excited throng; hands were convulsively grasped, and hats sent flying in the air; and in their wild joy they crushed around him and tried to lift him upon their shoulders.

The territorial allegiance and communal spirit celebrated and idealised by Kickham have died hard in Ireland. GAA club colours, for example were often drawn from old faction favours and, even now, an occasional faction slogan can still be heard. ‘If any man can, an Alley man can’. ‘Squeeze ‘em up Moycarkey and hang ‘em out to dry!’ Lingering animosities can sometimes surface in surprising ways: it is not unknown, for example, for an irate and disappointed Wexford hurling supporter (and what other kind of Wexford supporter is there?) to hurl abuse at Kilkenny, recalling an incident that occurred in Castlecomer to indignant Wexford United Irishmen: ‘Sure what good are they anyway? Didn’t they piss on the powder in ‘98?’ A possibly apocryphal incident occurred after a fiercely contested Cork-Tipperary match. Cork won but in Tipperary eyes that was solely due to a biased Limerick referee. When the disgruntled Tipperary supporters poured off the train at Thurles, they vented their frustrations on the only Limerick man they could find in the town – by tarring and feathering the statue of Archbishop Croke in the Square (presumably the only time in Irish history that a Catholic bishop has been tarred and feathered).

With the notable exception of Cork, the game has not been successfully transplanted into the cities. In Cork, close-knit working-class neighbourhoods like Blackrock and Gouldings Glen (home of Glen Rovers), and the strong antagonism between the hilly northside and the flat southside of the city, nourished the territoriality and community spirit so important to the game’s health. In Dublin, however, the modern suburbs, based on diversity, newness and mobility, have not proved hospitable receptacles of the game. Brendan Behan, brought up in the shadow of Croke Park, commented:

At home we played soccer in the street and sometimes a version of hurling, fast and sometimes savage, adapted from the long-pucking grace of Kilkenny and Tipperary to the crookeder, foreshortened, snappier brutality of the confines of a slum thoroughfare.

MICHAEL CUSACK & THE GAA