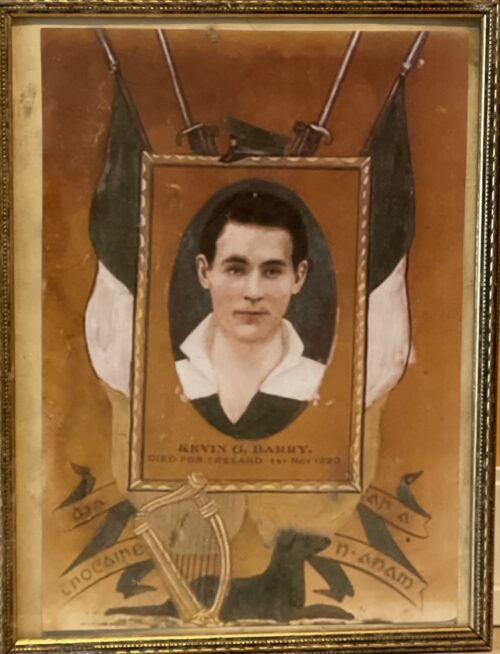

The iconic portrait of a teenage Kevin Barry,one of our most celebrated republican martyrs-in the black and white hooped rugby jersey of Belvedere College SJ.

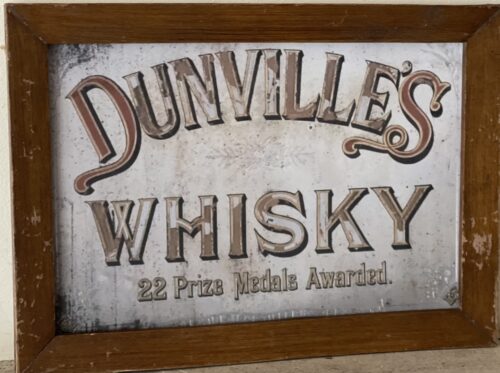

26cm x 30cm Dunmanway Co Cork

Kevin Gerard Barry (20 January 1902 – 1 November 1920) was an

Irish republican paramilitary who was executed by the British Government during the

Irish War of Independence. He was sentenced to death for his part in an attack upon a British Army supply lorry which resulted in the deaths of three British soldiers.

His execution inflamed nationalist public opinion in Ireland, largely because of his age. The timing of the execution, only days after the death by

hunger strike of

Terence MacSwiney, the republican

Lord Mayor of Cork, brought public opinion to a fever-pitch. His death attracted international attention, and attempts were made by U.S. and Vatican officials to secure a reprieve. His execution and MacSwiney's death precipitated an escalation in violence as the Irish War of Independence entered its bloodiest phase, and Barry became an Irish republican martyr.

Early life

Kevin Barry was born on 20 January 1902, at 8 Fleet Street,

Dublin, to Thomas and Mary (née Dowling) Barry. The fourth of seven children, two boys and five sisters, Kevin was baptised in St Andrew's Church, Westland Row. Thomas Barry Sr. worked on the family's farm at Tombeagh,

Hacketstown,

County Carlow, and ran a dairy business from Fleet Street. Thomas Barry Sr. died in 1908, aged 56.

His mother came from Drumguin, County Carlow, and, upon the death of her husband, moved the family to nearby Tombeagh. As a child he went to the national school in Rathvilly. On returning to Dublin, he attended

St Mary's College, Rathmines, until the school closed in the summer of 1916.

When he was thirteen, he attended a commemoration for the

Manchester Martyrs, who were hanged in

England in 1867. Afterwards he wished to join

Constance Markievicz's

Fianna Éireann, but was reportedly dissuaded by his family.

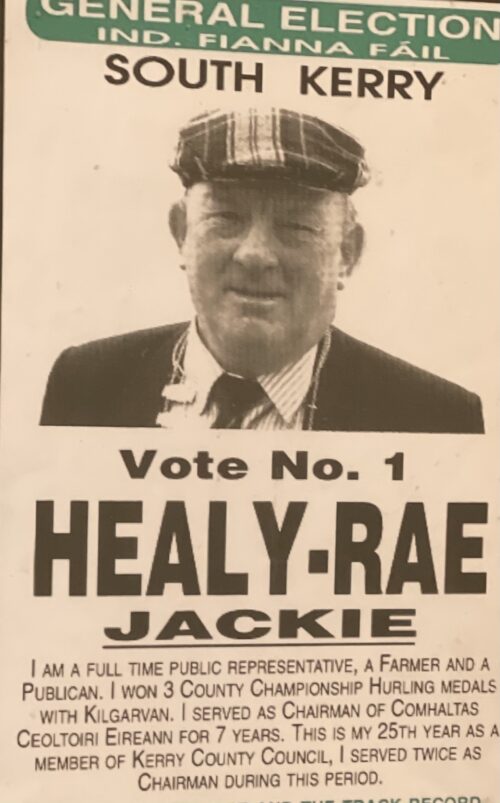

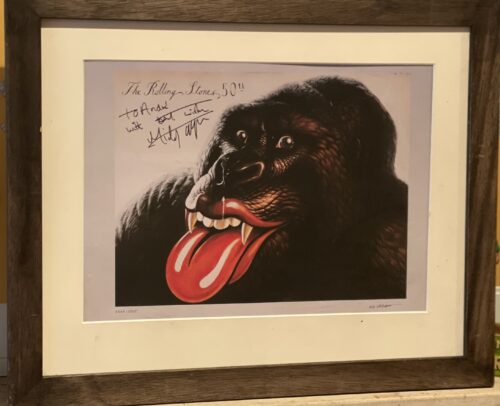

Belvedere College

From St Mary's College he transferred to

Belvedere College, where he was a member of the championship Junior Rugby Cup team, and earned a place on the senior team. In 1918 he became secretary of the school

hurling club which had just been formed, and was one of their most enthusiastic players.

Belvedere College, the Jesuit college attended by Kevin Barry. To mark the anniversary of his execution, Belvedere's museum mounted a special exhibition of Kevin Barry memorabilia.

A Jesuit priest, Thomas Counihan, who was Barry's science and mathematics teacher, said of him: "He was a dour kind of lad. But once he got down to something he went straight ahead… There was no waving of flags with him, but he was sincere and intense." Notwithstanding his many activities, he did not neglect his studies.

He won a merit-based scholarship given annually by

Dublin Corporation, which allowed him to become a student of medicine at

UCD.

Medical student

He entered

University College Dublin in 1919. His closest friend at college was Gerry MacAleer, from

Dungannon, whom he had first met in Belvedere. Other friends included

Frank Flood, Tom Kissane and Mick Robinson, who, unknown to many in the college, were, along with Barry, members of the

Irish Volunteers.

Volunteer activities

In October 1917, during his second year at Belvedere, aged 15, he joined the IRA.

Assigned originally to ‘C’ Company 1st Battalion, based on the north side of Dublin, he later transferred to the newly formed ‘H’ Company, under the command of Capt. Seamus Kavanagh. His first job as a member of the IRA was delivering mobilisation orders around the city. Along with other volunteers, Barry trained in a number of locations in Dublin, including the building at 44 Parnell Square, the present day headquarters of

Sinn Féin, now named Kevin Barry Hall. The IRA held Field exercises during this period which were conducted in north county Dublin and in areas such as

Finglas.

Wall plaque marking the site in 1919, where the Active Service Unit of the Dublin Brigade of the Irish Republican Army was founded. The building is in Great Denmark Street, Dublin.

The following year, at the age of 16, he was introduced by Seán O'Neill and Bob O'Flanagan to the Clarke Luby Club of the

IRB, which had been reorganised. He took part in a number of IRA operations in the years leading up to his capture. He was part of the unit which raided the Shamrock Works for weapons destined to be handed over to the

R.I.C. He also took part in the raid on Mark's of Capel Street, looking for ammunition and explosives. On 1 June 1920, under Vice-Commandant

Peadar Clancy, he played a notable part in the seizing of the King's Inn, capturing the garrison’s arms. The haul included 25 rifles, two light machine guns and large quantities of ammunition. The 25 British soldiers captured during the attack were released as the volunteers withdrew. In recognition of his dedication to duty he was promoted to Section Commander.

Ambush

On the morning of 20 September 1920, Barry went to Mass, then joined a party of IRA volunteers on

Bolton Street in Dublin. Their orders were to ambush a British army lorry as it picked up a delivery of bread from the bakery, and capture their weapons. The ambush was scheduled for 11:00am, which gave him enough time to take part in the operation and return to class in time for an examination he had at 2:00pm. The truck arrived late, and was under the command of Sergeant Banks.

Armed with a .38

Mauser Parabellum, Barry and members of C Company were to surround the lorry, disarm the soldiers, take the weapons and escape. He covered the back of the vehicle and, when challenged, the five soldiers complied with the order to lay down their weapons. A shot was then fired;

Terry Golway, author of

For the Cause of Liberty, suggests it was possibly a warning shot from an uncovered soldier in the front. Barry and the rest of the ambush party then opened fire. His gun jammed twice and he dived for cover under the vehicle. His comrades fled and he was left behind. He was then spotted and arrested by the soldiers.

One of the soldiers, Private Harold Washington, aged 15, had been shot dead. Two others, Privates Marshall Whitehead and Thomas Humphries, were both badly wounded and later died of their wounds.

The British Army released the following statement on Monday afternoon:

This morning a party of one N.C.O. and six men of the Duke of Wellington's Regiment were fired on by a body of civilians outside a bakery in Church Street, Dublin. One soldier was killed and four were wounded. A piquet of the Lancashire Fusiliers in the vicinity, hearing the shots, hurried to their comrades' assistance, and succeeded in arresting one of the aggressors. No arms or equipment were lost by the soldiers.

Much was made of Barry's age by Irish newspapers, but the British military pointed out that the three soldiers who had been killed were "much the same age as Barry". On 20 October, Major Reginald Ingram Marians OBE, Head of the Press Section of the General Staff, informed Basil Clarke, Head of Publicity, that Washington was "only 19 and that the other soldiers were of similar ages." General Macready

was well aware of the "propaganda value of the soldier's ages." Macready informed General

Sir Henry Wilson on the day that sentence was pronounced "of the three men who were killed by him (Barry) and his friends two were 19 and one 20 — official age so probably they were younger... so if you want propaganda there you are."

It was later confirmed that Private Harold Washington was 15 years and 351 days old, having been born 4 October 1904.

About this competing propaganda,

Martin Doherty wrote in a magazine article entitled 'Kevin Barry & the Anglo-Irish Propaganda War':

from the British point of view, therefore, the Anglo-Irish propaganda war was probably unwinable [sic]. Nationalist Ireland had decided that men like Kevin Barry fought to free their country, while British soldiers — young or not — sought to withhold that freedom. In these circumstances, to label Barry a murderer was merely to add insult to injury. The contrasting failure of British propaganda is graphically demonstrated by the simple fact that even in British newspapers Privates Whitehead, Washington and Humphries remained faceless names and numbers, for whom no songs were written.”

Capture and torture

Sinn Féin's Dublin HQ at the Kevin Barry Memorial Hall

Barry was placed in the back of the lorry with the young body of Private Harold Washington, and was subjected to some abuse

by Washington's comrades. He was transported then to the North Dublin Union. Upon arrival at the barracks he was taken under military police escort to the defaulters' room where he was searched and handcuffed. A short while later, three sergeants of the Lancashire Fusiliers and two officers began the interrogation. He gave his name and an address of 58 South Circular Road, Dublin (his uncle's address), and his occupation as a medical student, but refused to answer any other questions. The officers continued to demand the names of other republicans involved in the ambush.

At this time a publicity campaign was mounted by Sinn Féin. Barry received orders on 28 October from his brigade commander, Richard McKee, "to make a sworn affidavit concerning his torture in the North Dublin Union." Arrangements were made to deliver this through Barry's sister, Kathy, to

Desmond Fitzgerald, director of publicity for Sinn Féin, "with the object of having it published in the World press, and particularly in the English papers, on Saturday 30th October."

The affidavit, drawn up in Mountjoy Prison days before his execution, describes his treatment when the question of names was repeated:

He tried to persuade me to give the names, and I persisted in refusing. He then sent the sergeant out of the room for a bayonet. When it was brought in the sergeant was ordered by the same officer to point the bayonet at my stomach ... The sergeant then said that he would run the bayonet into me if I did not tell ... The same officer then said to me that if I persisted in my attitude he would turn me out to the men in the barrack square, and he supposed I knew what that meant with the men in their present temper. I said nothing. He ordered the sergeants to put me face down on the floor and twist my arm ... When I lay on the floor, one of the sergeants knelt on my back, the other two placed one foot each on my back and left shoulder, and the man who knelt on me twisted my right arm, holding it by the wrist with one hand, while he held my hair with the other to pull back my head. The arm was twisted from the elbow joint. This continued, to the best of my judgment, for five minutes. It was very painful ... I still persisted in refusing to answer these questions... A civilian came in and repeated the questions, with the same result. He informed me that if I gave all the information I knew I could get off.

On 28 October, the

Irish Bulletin (organised by

Dick McKee, the IRA Commandant of the Dublin Brigade), a news-sheet produced by Dáil Éireann's Department of Publicity,

published Barry's statement alleging torture. The headline read:

English Military Government Torture a Prisoner of War and are about to Hang him. The

Irish Bulletin declared Barry to be a

prisoner of war, suggesting a conflict of principles was at the heart of the conflict. The English did not recognise a war and treated all killings by the IRA as murder. Irish republicans claimed that they were at war and it was being fought between two opposing nations and therefore demanded prisoner of war status.

Historian John Ainsworth, author of

Kevin Barry, the Incident at Monk's bakery and the Making of an Irish Republican Legend, pointed out that Barry had been captured by the British not as a uniformed soldier but disguised as a civilian and in possession of

flat-nosed "Dum-dum" bullets, which expand upon impact, maximising the amount of damage done to the "unfortunate individual" targeted, in contravention of the

Hague Convention of 1899.

Erskine Childers addressed the question of political status in a letter to the press on 29 October, which was published the day after Barry's execution.

-

- This lad Barry was doing precisely what Englishmen would be doing under the same circumstances and with the same bitter and intolerable provocation — the suppression by military force of their country's liberty.

- To hang him for murder is an insulting outrage, and it is more: it is an abuse of power: an unworthy act of vengeance. contrasting ill with the forbearance and humanity invariably shown by the Irish Volunteers towards the prisoners captured by them when they have been successful in encounters similar to this one. These guerrilla combats with soldiers and constables — both classes do the same work with the same weapons; the work of military repression — are typical episodes in Ireland.

- Murder of individual constables, miscalled ‘police’, have been comparatively rare. The Government figure is 38, and it will not, to my knowledge, bear examination. I charge against the British Government 80 murders by soldiers and constables: murders of unarmed people, and for the most part wholly innocent people, including old men, women and boys.

- To hang Barry is to push to its logical extreme the hypocritical pretense that the national movement in Ireland unflinchingly supported by the great mass of the Irish people, is the squalid conspiracy of a ‘murder gang’.

- That is false; it is a natural uprising: a collision between two Governments, one resting on consent, the other on force. The Irish are struggling against overwhelming odds to defend their own elected institutions against extinction.

In a letter addressed to

"the civilised nations of the world",

Arthur Griffith — then acting President of the Republic wrote:

-

-

-

Under similar circumstances a body of Irish Volunteers captured on June 1 of the present year a party of 25 English military who were on duty at the King's Inns, Dublin. Having disarmed the party the Volunteers immediately released their prisoners. This was in strict accordance with the conduct of the Volunteers in all such encounters. Hundreds of members of the armed forces have been from time to time captured by the Volunteers and in no case was any prisoner maltreated even though Volunteers had been killed and wounded in the fighting, as in the case of Cloyne, Co. Cork, when, after a conflict in which one Volunteer was killed and two wounded, the whole of the opposing forces were captured, disarmed, and set at liberty.

Ainsworth notes that "Griffith was deliberately using examples relating to IRA engagements with British military forces rather than the police, for he knew that engagements involving the police in particular were usually of an uncivilized nature, characterized by violence and brutality, albeit on both sides by this stage."

Trial

The War Office ordered that Kevin Barry be tried by

court-martial under the

Restoration of Order in Ireland Act, which received

Royal Assent on 9 August 1920. General Sir

Nevil Macready, Commander-in-Chief of British forces in Ireland then nominated a court of nine officers under a Brigadier-General Onslow.

Kevin Barry Commemorative Plaque close to the spot where he was captured on Church Street, Dublin

On 20 October, at 10 o’clock, the nine officers of the court — ranging in rank from Brigadier to Lieutenant — took their places at an elevated table. At 10.25,

Kevin Barry was brought into the room by a military escort. Then Seán Ó hUadhaigh sought a short adjournment to consult his client. The court granted this request. After the short adjournment Barry announced "As a soldier of the Irish Republic, I refuse to recognise the court." Brigadier Onslow explained the prisoner's "perilous situation" and that he was being tried on a capital charge. He did not reply. Ó hUadhaigh then rose to tell the court that since his client did not recognise the authority of the court he himself could take no further part in the proceedings.

Barry was charged on three counts of the murder of Private Marshall Whitehead. One of the bullets taken from Whitehead's body was of .45 calibre, while all witnesses stated that Barry was armed with a .38 Mauser Parabellum. The

Judge Advocate General informed the court that the Crown had only to prove that the accused was one of the party that killed three British soldiers, and every member of the party was technically guilty of murder. In accordance with military procedure the verdict was not announced in court. He was returned to Mountjoy, and at about 8 o’clock that night, the district court-martial officer entered his cell and read out the sentence: death by hanging. The public learned on 28 October that the date of execution had been fixed for 1 November.

Execution

Barry spent the last day of his life preparing for death. His ordeal focused world attention on Ireland. According to Sean Cronin, author of a biography of Barry (

Kevin Barry), he hoped for a firing squad rather than the gallows, as he had been condemned by a military court. A friend who visited him in Mountjoy prison after he received confirmation of the death sentence, said:

He is meeting death as he met life with courage but with nothing of the braggart. He does not believe that he is doing anything wonderfully heroic. Again and again he has begged that no fuss be made about him.

He reported Barry as saying "It is nothing, to give one's life for Ireland. I'm not the first and maybe I won't be the last. What's my life compared with the cause?"

Barry joked about his death with his sister Kathy. "Well, they are not going to let me like a soldier fall… But I must say they are going to hang me like a gentleman." This was, according to Cronin, a reference to

George Bernard Shaw's

The Devil's Disciple, the last play Kevin and his sister had seen together.

On 31 October, he was allowed three visits of three people each, the last of which was taken by his mother, brother and sisters. In addition to the two Auxiliaries with him, there were five or six warders in the boardroom. As his family were leaving, they met Canon John Waters, on the way in, who said, "This boy does not seem to realise he is going to die in the morning." Mrs Barry asked him what he meant. He said: "He is so gay and light-hearted all the time. If he fully realised it, he would be overwhelmed." Mrs Barry replied, "Canon Waters, I know you are not a Republican. But is it impossible for you to understand that my son is actually proud to die for the Republic?" Canon Waters became somewhat flustered as they parted. The Barry family recorded that they were upset by this encounter because they considered the chief chaplain "the nearest thing to a friend that Kevin would see before his death, and he seemed so alien."

Plaque placed by the Irish Government on the graves of the Volunteers

Kevin Barry was hanged on 1 November, after hearing two Masses in his cell. Canon Waters, who walked with him to the scaffold, wrote to Barry's mother later, "You are the mother, my dear Mrs Barry, of one of the bravest and best boys I have ever known. His death was one of the most holy, and your dear boy is waiting for you now, beyond the reach of sorrow or trial."

Dublin Corporation met on the Monday, and passed a vote of sympathy with the Barry family, and adjourned the meeting as a mark of respect. The Chief Secretary's office in Dublin Castle, on the Monday night, released the following communiqué:

The sentence of death by hanging passed by court-martial upon Kevin Barry, or Berry, medical student, aged 18½ years, for the murder of Private Whitehead in Dublin on September 20, was duly executed this morning at Mountjoy Prison, Dublin.

At a military court of inquiry, held subsequently in lieu of an inquest, medical evidence was given to the effect that death was instantaneous. The court found that the sentence had been carried out in accordance with law.

Barry's body was buried at 1.30 p.m, in a plot near the women's prison. His comrade and fellow-student

Frank Flood was buried alongside him four months later. A plain cross marked their graves and those of

Patrick Moran,

Thomas Whelan,

Thomas Traynor,

Patrick Doyle,

Thomas Bryan,

Bernard Ryan,

Edmond Foley and

Patrick Maher who were hanged in the same prison before the

Anglo-Irish Treaty of July 1921 which ended hostilities between Irish republicans and the British.The men had been buried in unconsecrated ground on the jail property and their graves went unidentified until 1934.They became known as

The Forgotten Ten by republicans campaigning for the bodies to be reburied with honour and proper rites.

On 14 October 2001, the remains of these ten men were given a

state funeral and moved from Mountjoy Prison to be re-interred at Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin.

Aftermath

On 14 October 2001 the remains of Kevin Barry and nine other volunteers from the War of Independence were given a state funeral and moved from

Mountjoy Prison to be re-interred at

Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin. Barry's grave is the first on the left.

The only full-length biography of Kevin Barry was written by his nephew, journalist Donal O'Donovan, published in 1989 as

Kevin Barry and his Time. In 1965, Sean Cronin wrote a short biography, simply entitled "Kevin Barry"; this was published by The National Publications Committee, Cork, to which

Tom Barry provided a foreword. Barry is remembered in a well-known song about his imprisonment and execution, written shortly after his death and still sung today. The tune to

"Kevin Barry" was taken from the sea-shanty "Rolling Home".

[17] The execution reportedly inspired

Thomas MacGreevy's surrealist poem,

"Homage to Hieronymus Bosch". MacGreevy had unsuccessfully petitioned the Provost of

Trinity College Dublin,

John Henry Bernard, to make representations on Barry's behalf.

A commemorative stamp was issued by

An Post to mark the 50th anniversary of Barry's death in 1970.

[18]

The

University College Dublin and

National University of Ireland, Galway branches of

Ógra Fianna Fáil are named after him.

[19] Derrylaughan Kevin Barry's GAA club was founded in

Clonoe,

County Tyrone.

In 1930, Irish immigrants in

Hartford, Connecticut, created

a hurling club and named it after Barry. The club later disappeared for decades, but was revived in 2011 by more recently arrived Irish immigrants and local Irish-Americans in the area.

[20]

In 1934, a large stained-glass window commemorating Barry was unveiled in Earlsfort Terrace, then the principal campus of

University College Dublin. It was designed by Richard King of the

Harry Clarke Studio. In 2007, UCD completed its relocation to the

Belfield campus some four miles away and a fund was collected by graduates to defray the cost (estimated at close to €250,000) of restoring and moving the window to this new location.

[21] A grandnephew of Kevin Barry is Irish historian

Eunan O'Halpin.

[22]

There is an Irish republican

flute band named after him, the "Volunteer Kevin Barry Republican Flute Band", which operates out of the Calton area of the city.

[citation needed]

Barry's execution is mentioned in the folk song "

Rifles of the I.R.A." written by

Dominic Behan in 1968. A

ballad bearing Barry's name, relating the story of his execution, has been sung by artists as diverse as

Paul Robeson,

[23] Leonard Cohen,

[24] Lonnie Donegan, and

The Dubliners.

At the place where Kevin Barry was captured (North King Street/Church Street, Dublin), there are two blocks of flats named after him.

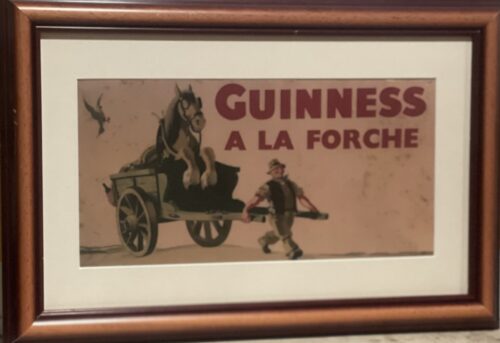

58cm x 47cm

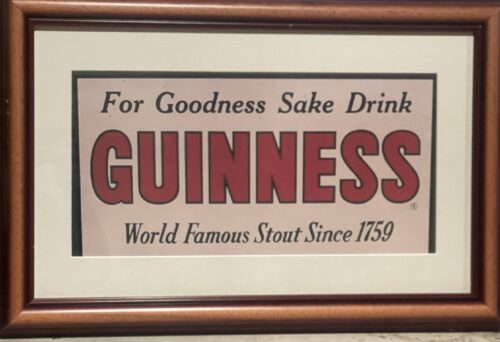

58cm x 47cm