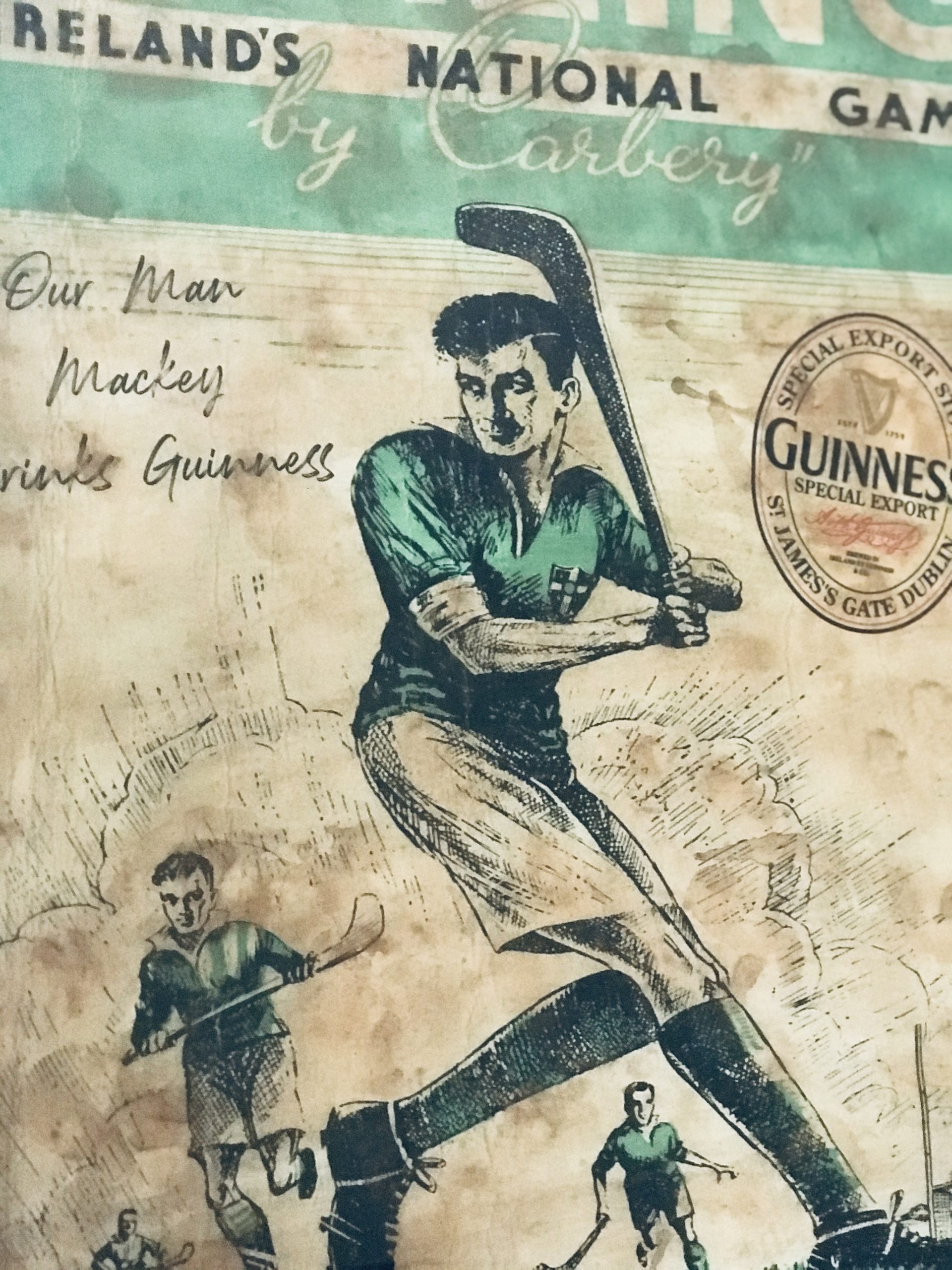

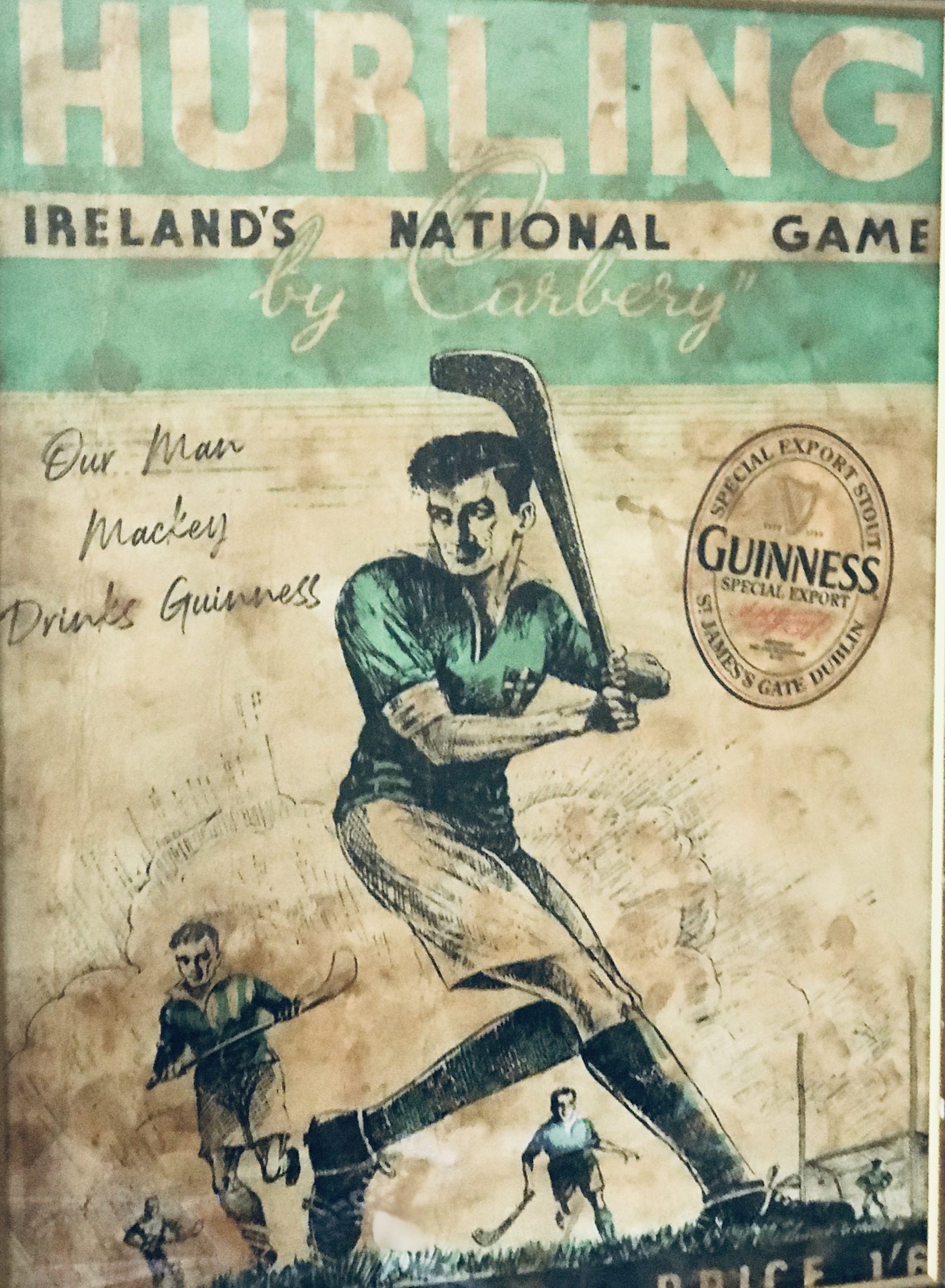

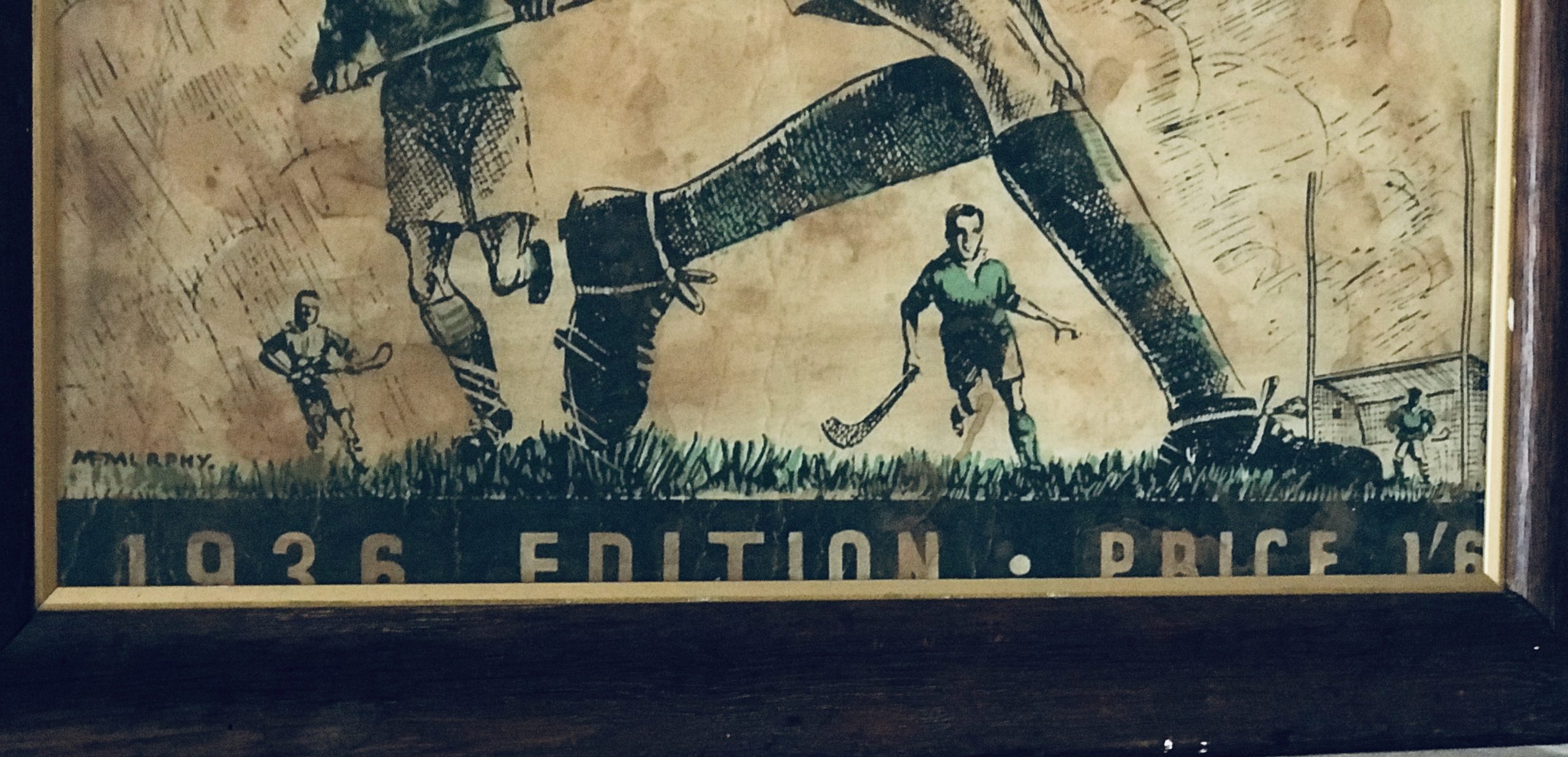

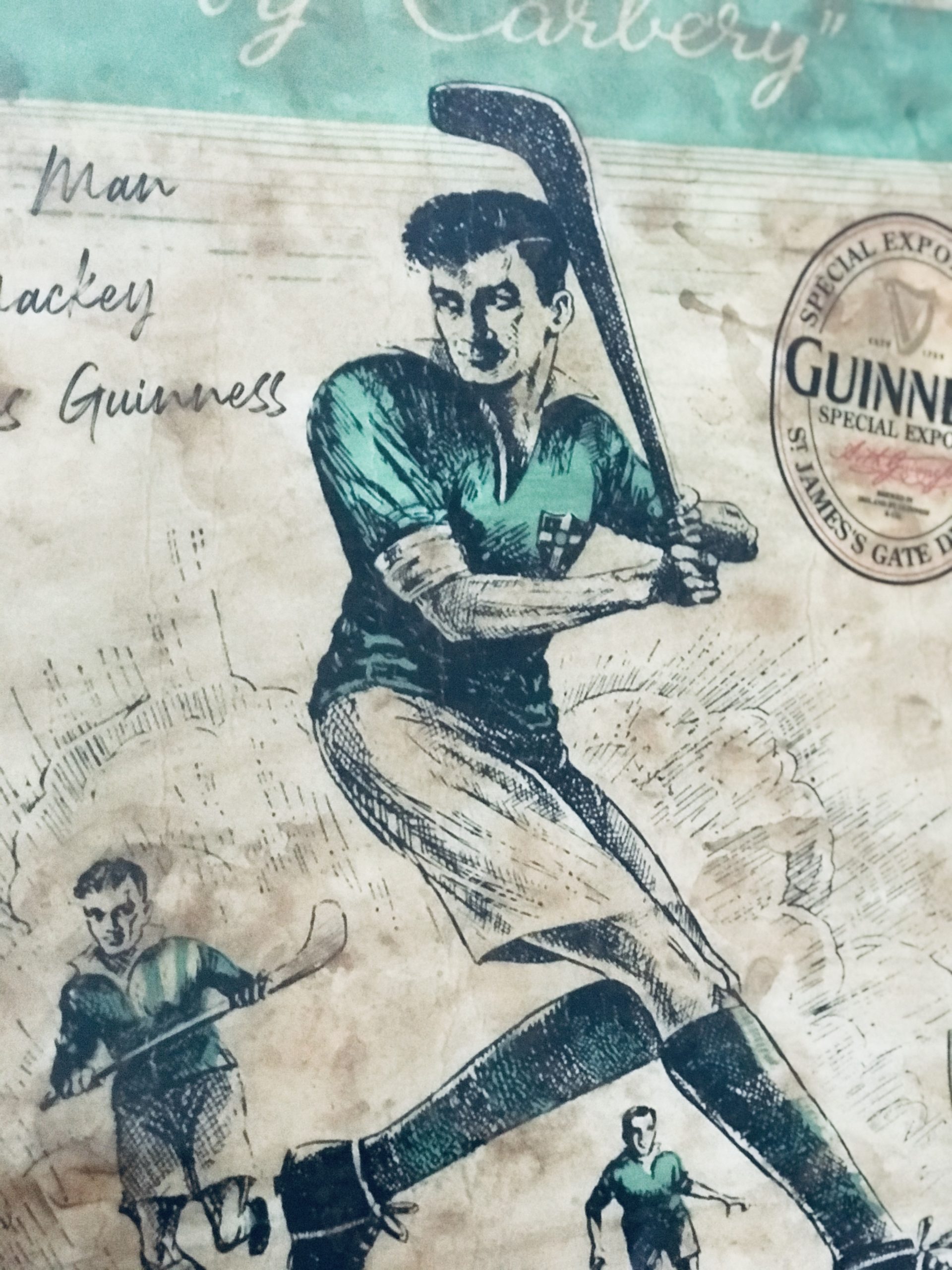

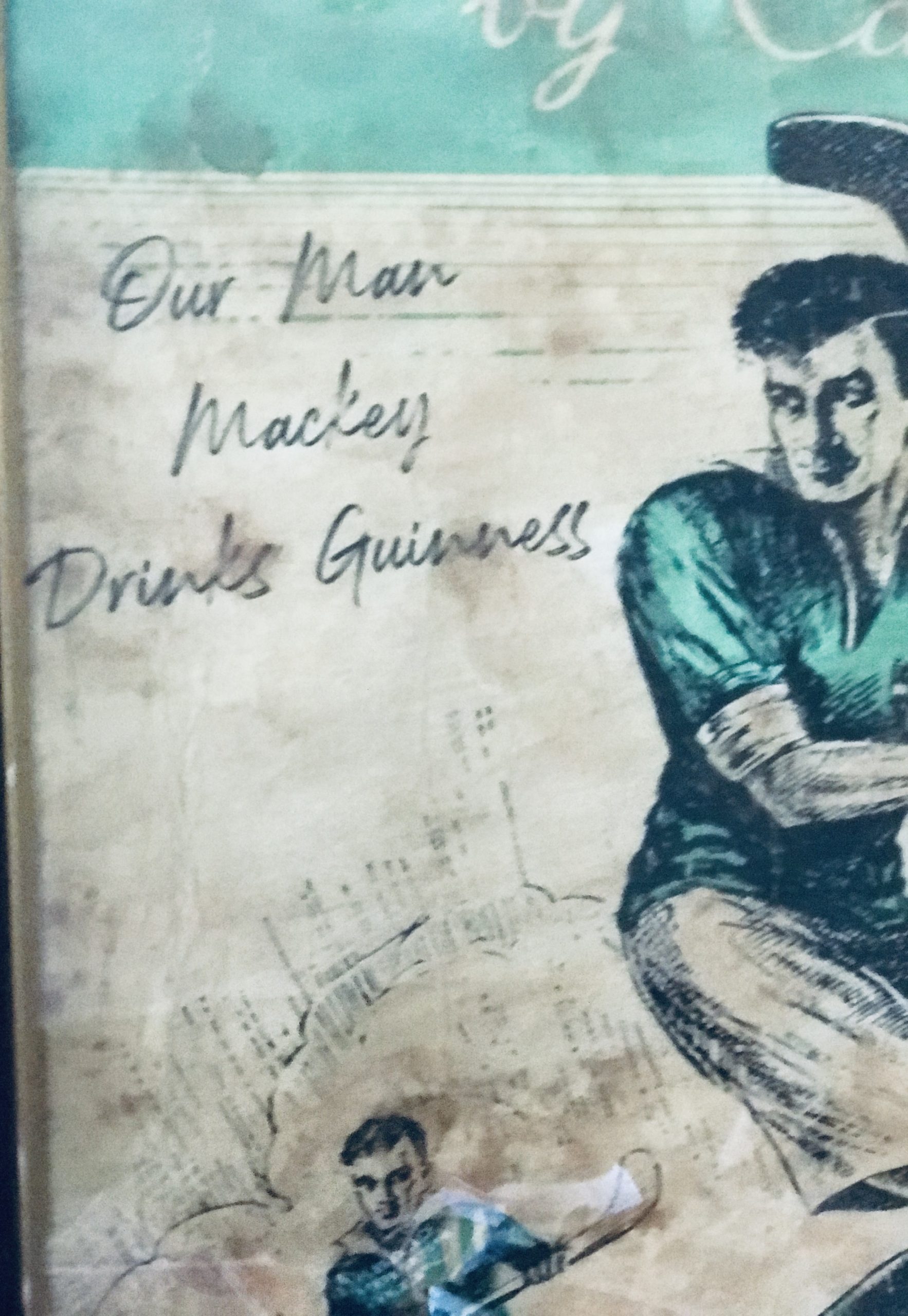

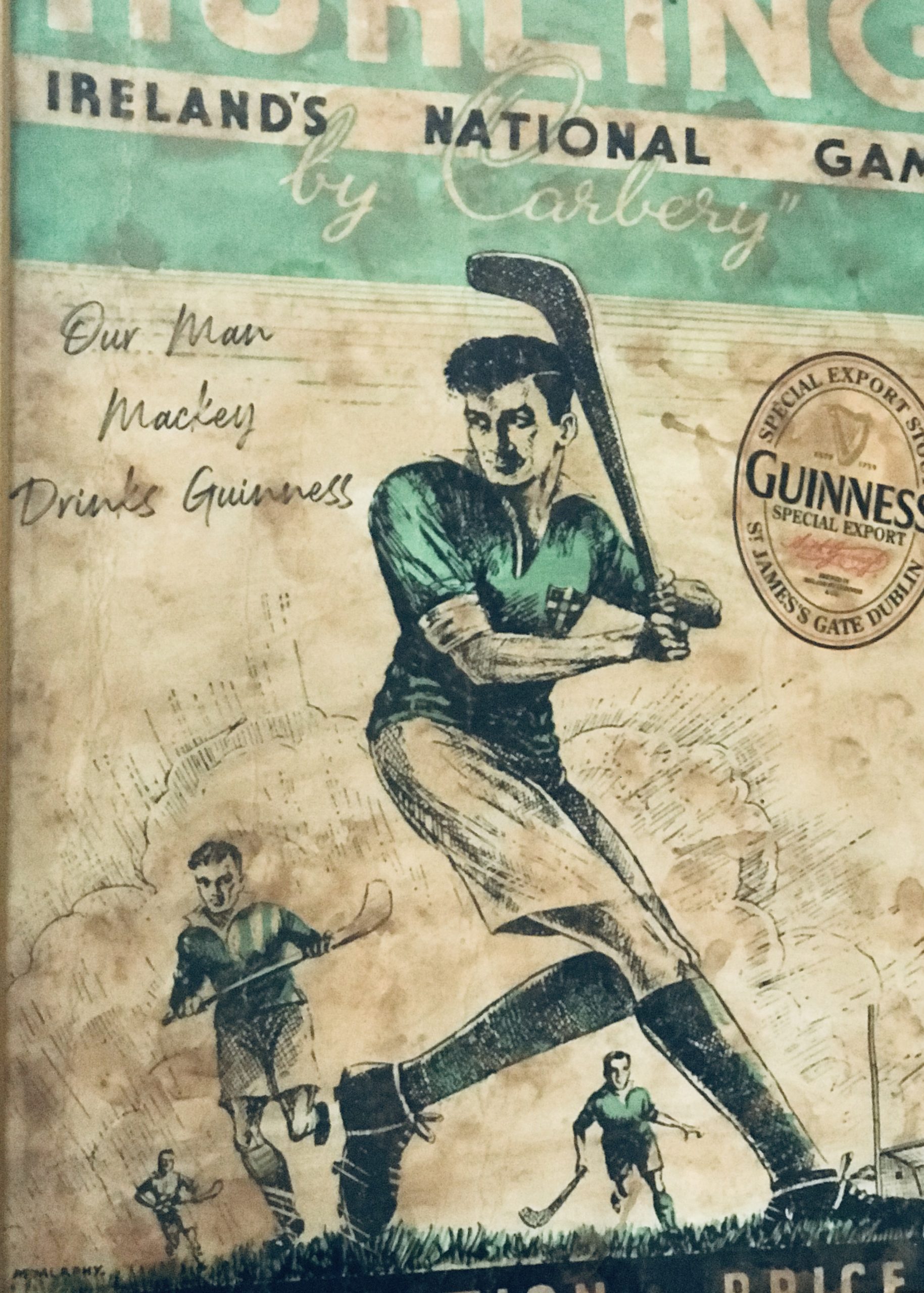

Magnificent and rare limited edition print of advert promoting Hurling-Irelands national game (By the legendary GAA Journalist Carbery) and Guinness with the legendary Limerick hurler Mick Mackey to the fore in the sketched advertisement.To the left of the image is the hand written note- “Our man Mackey drinks Guinness”.

70cm x 55cm Dromcollogher Co Limerick

PD Mehigan (aka Carbery) was a singular individual, a prominent figure in the first five decades of the history of the Irish Free State.

His interests and achievements are extensive and fascinating.

In the summer of 1926, Irish people’s experience of sport was turned on its head.

The turning began when PS O’Hegarty, the man who ran the Department of Posts and Telegraphs and who founded an Irish state radio service — 2RN — met Mehigan, then the leading GAA journalist in the country, and made him a proposition.

The story of what happened between the two men was later told by Mehigan: “In his blunt, direct way, he (O’Hegarty) slung the question at me: ‘Mehigan, will you help us by giving a running commentary — describe the match as you see it — from the Hogan Stand?’”

Mehigan agreed he would, indeed, broadcast a match, with live commentary, on 2RN.

It was an epic game, fitted perfectly to a landmark moment in broadcasting.

Indeed, many had doubted it was technically possible to achieve what was broadcast from Croke Park on that day.

After all, there was no tradition of broadcasting sports events in Europe and the new Irish state’s national radio station (run by O’Hegarty) had only been broadcasting from the GPO, in Dublin, for a mere eight months.

For Mehigan, it was an utterly unique experience: “I was at Croke Park an hour before the match. The mysterious signal came that I was ‘on the air’ and the engineer nodded to me to fire away.

“Without much ado, I fired away and found I could spout freely enough, particularly as soon as the game, which I was so familiar with, started.”

Mehigan continued: “At half-time, I had to do a summary of the first-half, and so on, to the end. I was very tired at the finish; they were beaming in the engineers’ room below and clapped me on the back. I knew I was a raw recruit and had a lot to learn. Yet, I got a great kick out of it all, and was glad to help to spread the light about the loved game of my boyhood.”

Mehigan’s memories of the day capture the pioneering nature of what was achieved in Dublin: “To the Gaelic Athletic Association and to 2RN (as Raidió Éireann was then called) belongs the honour of giving the first open-air games broadcast to Europe and to the western world.”

This was an exaggeration, as other sports had been broadcast in America and from Spain.

Allowing for that, the contrast with what the BBC had managed in England was stark.

No sports broadcast had been managed on that station, despite plans to commentate on the England-Scotland rugby international, the FA Cup final, the Oxford-Cambridge boat race, and the Epsom Derby.

Basically, the sporting organisations of Britain did not facilitate such commentary.

They were, for instance, exceptionally concerned about the impact live commentary might have on attendances and were concerned, also, about the image of their sports.

For PD Mehigan, this was another successful venture in what was a remarkable career.

He had been born and schooled in Ardfield, in Cork, before joining the civil service in 1899. He worked in the Department of Customs and Excise, before moving to London.

While there, he played on the London team that was hammered by Cork in the 1902 All-Ireland final.

Moving back to Cork, he played in the 1905 All-Ireland final — losing to Kilkenny — and was also Irish champion in the hop, skip, and jump, in 1908.

While still working as a customs officer, he began to write a column for The Cork Examiner, in 1912, under the pseudonym ‘Carbery’.

He continued to write for the Examiner on GAA, boxing, coursing and other sports, even after he moved back to Dublin, in 1922. He and his wife moved to Dartmouth Square, in Ranelagh, where they raised six children.

His life was transformed by radio broadcasting. He commentated on more than 100 matches and became a household name.

The opportunities that now opened up for Mehigan in journalism allowed him to leave the civil service and, as well as writing as ‘Carbery’ for the Examiner, he also wrote for The Irish Times, as ‘Pat O’, on Gaelic games and coursing.

To say it was unusual in the 1930s to leave a steady job in the civil service to embark on a career as a fulltime writer does not come close to doing justice to the courage of this move.

With an expanding family to support, he worked year after year to develop new initiatives. His great innovation was the compilation of Carbery’s Annual in 1939.

This publication drew together his many talents. In this annual, he wrote on sport, history, and on the natural world, with his poetry and short stories adding creativity to his reportage.

Mehigan also wrote numerous books (as ‘Carbery’), usually on sport, but he also published a collection of his fictional works and reflections on nature and Irish history, as Sean Kearns noted in his excellent account of Mehigan’s life, published in the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

His most successful books were Hurling: Ireland’s National Game (1940), Gaelic Football (1941), and Fifty Years of Irish Athletics (1943).

Vintage Carbery, a lovely collection of his writings, can be found in the corner of some secondhand bookshops.

It was published in 1984, having been compiled by the former Irish Times journalist Sean Kilfeather.

In a fine introduction to the collection, Kilfeather writes that Mehigan was a remarkable man, whose writing was “lively” and “evocative”.

More than that, he recalls that Mehigan managed the seemingly impossible feat of being “loved and respected” by his colleagues in sports journalism.

In Vintage Carbery, Mehigan tells the story of his days as a radio commentator and finishes with a story of his greatest thrill from those years: Getting a scoop of an interview with world heavyweight boxing champion, Gene Tunney, who had just dethroned Jack Dempsey.

Tunney was in Dublin in 1928 to attend the Tailteann Games, when Mehigan approached him for an interview. Tunney said no. Mehigan persisted. Tunney still said no.

“‘We’re hooked up to all of Europe.’ No good. His face was still stoic. ‘We’re hooked up to all of America,’ I urged. No cord touched! Another brainwave came.

“I knew Tunney came especially to see his blood relations in Mayo and Cork. I spoke my tenderest: ‘We’re hooked up’, I said, ‘to every homestead in Mayo and every village in Co. Cork!’ His fine eyes softened. Meekly, silently, he walked to the microphone. I introduced him in 40 words and he was on the air.”

It was one more coup for a man whose career was defined by a capacity to break the mould.

Michael John Mackey (12 July 1912 – 13 September 1982) was an Irish hurler who played as a centre-forward for the Limerick senior team.

Born in Castleconnell, County Limerick, Mackey first arrived on the inter-county scene at the age of seventeen when he first linked up with the Limerick minor team, before later lining out with the junior side. He made his senior debut in the 1930–31 National League. Mackey went on to play a key part for Limerick during a golden age for the team, and won three All-Ireland medals, five Munster medals and five National Hurling League medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on two occasions, Mackey also captained the team to two All-Ireland victories.

His brother, John Mackey, also shared in these victories while his father, “Tyler” Mackey was a one-time All-Ireland runner-up with Limerick.

Mackey represented the Munster inter-provincial team for twelve years, winning eight Railway Cup medals during that period. At club level he won fifteen championship medals with Ahane.

Throughout his inter-county career, Mackey made 42 championship appearances for Limerick. His retirement came following the conclusion of the 1947 championship.

In retirement from playing, Mackey became involved in team management and coaching. As trainer of the Limerick senior team in 1955, he guided them to Munster victory. He also served as a selector on various occasions with both Limerick and Munster. Mackey also served as a referee.

Mackey is widely regarded as one of the greatest hurlers in the history of the game. He was the inaugural recipient of the All-Time All-Star Award. He has been repeatedly voted onto teams made up of the sport’s greats, including at centre-forward on the Hurling Team of the Century in 1984 and the Hurling Team of the Millennium in 2000.

Mackey was just fourteen years-old when the Ahane club was formed in 1926. Deemed too young to play at the time, he made his club debut in September 1928 in a junior championship defeat of Fedamore. It was a successful campaign that ended with the county final on 16 June 1929. A 5–1 to 2–2 defeat of Kilmeedy gave Mackey a junior championship medal.

1929 also proved to be a successful year for Mackey. A 1–8 to 1–2 defeat of Cappamore gave him an intermediate championship medal.

Mackey continued his winning ways in 1930, winning a minor championship medal following a victory over Doon. He had earlier won a minor championship medal with Clonlara when he briefly played in Clare.

In 1931 Mackey was a key part of the Ahane team that reached the final of the senior championship. A 5–5 to 1–4 trouncing of Croom gave Ahane their first senior title, while it also gave Mackey his first championship medal.

Ahane failed to retain their title, however, Mackey’s team returned to the championship decider once again in 1933. A 1–7 to 1–1 defeat of Croom gave him his second championship medal. It was the beginning of a run of success, as Ahane went on to dominated club hurling in Limerick for the rest of the decade. Back-to-back defeats of Kildimo in 1934 and 1935, followed by four successive defeats of Croom brought Mackey’s championship medal tally to eight.

Eight-in-a-row proved beyond Ahane, as Croom triumphed in 1940 and 1941.

During this time Mackey also starred with the Ahane senior football team. Five successive final victories between 1935 and 1939 gave him championship medals in the other code also.

Ahane hurlers bounced back in 1942 to reach a tenth successive county decider. A 7–8 to 1–0 defeat of Rathkeale gave Mackey an eight winners’ medal in the hurling championship. This victory set Ahane off on another great run of success. Further defeats of Croom (twice), Rathkeale (twice), Granagh-Ballingarry and St. Patrick’s yielded another seven championships in succession. These victories brought Mackey’s championship medal to a remarkable fifteen.

Mackey’s last appearance for Ahane was in 1951 in a championship semi-final defeat by Treaty Sarsfield’s. The game was not an eventful one for Mackey as he was seny off.

Minor and junior

Mackey made his inter-county debut with Limerick in the minor provincial championship in August 1929. It was an unsuccessful start as Waterford were the winners.

As well as lining out for the Limerick minor team again in 1930, Mackey was also a member of the Limerick junior team. Once again, success was not forthcoming as Tipperary put Limerick out of the provincial championship after a thrilling draw and a replay.

Beginnings

By this stage Mackey had joined the Limerick senior team. In spite of just turning seventeen, he was listed as a substitute for the provincial championship campaign in 1929.

After being dropped from the team in 1930, Mackey’s senior debut came about in unusual circumstances. In a National Hurling League game against Kilkenny on 16 November 1930, Limerick were unable to field a full team and resorted to looking for players in the crowd. Mackey, who had gone to the game as a spectator, was asked to play and duly made his senior inter-county debut.

Dominance

In 1933 Limerick emerged as a major force after a decade in the doldrums. Mackey lined out in his first Munster decider that year, as Limerick faced Waterford. With eight minutes left in the game, some spectators invaded the pitch and the match was abandoned. Since Limerick were winning by 3–7 to 1–2, the Munster Council declared them the champions and Mackey collected his first Munster medal. The subsequent All-Ireland final on 3 September 1933 saw a record crowd of 45,176 travel to Croke Park to see Limerick face Kilkenny. After being level at the interval, the game remained close in the second half until a solo-run goal by Johnny Dunne sealed a 1–7 to 0–6 victory for Kilkenny.

A successful league campaign throughout 1933–34 saw Limerick reach the decider against Dublin. In spite of home advantage, Limerick had to battle hard for a 3–6 to 3–3 victory. It was Mackey’s first National League medal. The subsequent provincial championship saw Limerick reach the decider, where they played Waterford for the second year in-a-row. The result was much the same, with Mackey collecting a second Munster medal following a 4–8 to 2–5 victory. The All-Ireland final on 2 September 1934 was a special occasion as it was the golden jubilee final of the Gaelic Athletic Association. Dublin were the opponents and a close game developed. After leading by a point at the interval, Limerick went five clear with time running out. Dublin fought their way back to secure a remarkable draw. The replay on 30 September turned out to be an even closer affair, with both sides level with two minutes to go. Points from Mackey and Jackie O’Connell and a remarkable four goals from Dave Clohessy secured a 5–2 to 2–6 victory for Limerick. The win gave Mackey an All-Ireland medal for Mackey.

Mackey added a second National League medal to his collection in 1935, as Limerick retained their title in a straightforward league format. Limerick dominated the provincial series of games once again, and lined out in the decider against Tipperary. Mackey was singled out for particular praise, and collected a third Munster medal following a 5–5 to 1–4 victory. Kilkenny were Limerick’s opponents in the subsequent All-Ireland final on 1 September 1935 and, once again, the game was a close affair. Limerick were the red-hot favourites as a record crowd of over 46,000 turned up to watch a hurling classic. In spite of rain falling throughout the entire game both sides served up a great game. At the beginning of the second-half Lory Meagher sent over a huge point from midfield giving Kilkenny a lead which they would not surrender. The game ended in controversial circumstances for Mackey when Limerick were awarded a close-in free to level the game. Jack Keane issued an instruction from the sideline that Timmy Ryan, the team captain, was to take the free and put the sliotar over the bar for the equalising point. As he lined up to take it, Mackey pushed him aside and took the free himself. The shot dropped short and into the waiting hands of the Kilkenny goalkeeper and was cleared. The game ended shortly after with Kilkenny triumphing by 2–5 to 2–4.

Limerick began 1936 by retaining their league title, having won seven of their games and drawing one. It was Mackey’s third National League medal. The team later embarked on a tour of the United States where they defeated a New York team made up of Irish expatriates. As a result of the tour Limerick were awarded a bye into the Munster final, however, Mackey, who was now captain of the side, sustained an injury to his right knee during the American tour. Tipperary provided the opposition in the provincial final and any sign of weakness from Mackey would be pounced upon. The Limerick selectors then hit on the novel idea of putting a large bandage on their star player’s uninjured left knee in an effort to confuse the Tipp players. The switching of bandages worked perfectly as Mackey scored a remarkable 5–3 as Limerick trounced the opposition. After scoring his final goal, he taunted the Tipperary fans with gestures, and finally turned his back to them and dropped his togs exposing his buttocks. Galway fell to Limerick in the subsequent All-Ireland semi-final, however, the men from the West lost the game after walking off the pitch with fifteen minutes left. They were not impressed with the rough tactics of their opponents. For the third time in four years the lure of a Kilkenny-Limerick clash brought a record crowd of over 50,000 to Croke Park for the All-Ireland decider on 6 September 1936. The first half produced a game that lived up to the previous clashes, and Limerick had a two-point advantage at half-time. Jackie Power scored two first-half goals, while a solo-run goal by captain Mackey in the second-half helped Limerick to a 5–6 to 1–5 victory. Mackey had won a second All-Ireland medal, while he also had the honour of lifting the Liam MacCarthy Cup.

Final success and decline

In 1937 Mackey captained Limerick to yet another National League title, his fourth overall. Limerick’s bid for a record-equalling fifth successive Munster crown came to an end in the provincial decider when Tipperary were victorious.

Limerick entered the record books in 1938 as the first team to win five consecutive National League titles. It is a record which has never been equalled. Mackey played a key role in all five of the victories.

A period of decline followed for Limerick, with many people believing that the team’s best days were behind them. This certainly seemed the case in 1940 when it took two late goals from Jackie Power and a storming display by Mackey to level the Munster semi-final with Waterford. Another late rally gave Limerick a victory in the subsequent replay. Mackey’s side put in another excellent performance in the Munster final to draw the game with Cork. At half-time in the replay Limerick looked like a spent force. Held scoreless for the entire thirty minutes, Mackey got the recovery underway in the second-half with a point from a seventy. He later moved back to the defence where Cork were running riot with goals. A pitch invasion scuppered the game for ten minutes, however, Limerick held on to win by 3–3 to 2–4 and Mackey collected a fifth Munster medal. The subsequent All-Ireland decider on 1 September 1940 brought Kilkenny and Limerick together for the last great game between the two outstanding teams of the decade. Early in the second-half Kilkenny took a four-point lead, however, once Mackey was deployed at midfield he proceeded to dominate the game. Limerick hung on to win the game on a score line of 3–7 to 1–7. The win gave Mackey his third All-Ireland medal, while he also joined an elite group of players who collected the Liam MacCarthy Cup more than once as captain.

Limerick took a back seat to Cork and Tipperary in the Munster series of games for the next few years.

Mackey played no championship hurling with Limerick in 1941, as he withdrew from the panel due to the death of his younger brother Paddy.

In 1944 Limerick squared up to Cork in the provincial final as the Leesiders were aiming for a fourth consecutive All-Ireland final victory. Mackey was a veteran hurler by now, however, he still seemed to be playing better than ever. Cork took an early lead, however, the Ahane man kept his team in with a chance by scoring points from almost impossible angles. He later powered past Con Murphy to score two quick goals and put Limerick in the driving seat once again. Cork came back, however, to draw the game on a remarkable 4–14 to 6–7 score line. In the last fifteen minutes of the subsequent replay Limerick were up by four points. Mackey broke through the Cork defence to score another inspiring goal, however, he was deemed to be fouled as he went through and the goal was disallowed. A free was awarded instead but it was missed. With minutes left in the game both sides were level and Mackey launched one last attack for the winning point. His shot hit the outside of the post and dropped wide. Only seconds remained when Cork’s Christy Ring caught the sliotar and fired a fierce shot into the net to win the game. Many regard this dramatic passage of play as the moment that the mantle of hurling’s star player passed from Mackey to Ring.

Following a defeat by Cork in the Munster decider in 1946, Mackey effectively retired from inter-county hurling. He was, however, coaxed back as a substitute for the 1947 Munster final defeat by Cork.

Inter-provincial

Mackey also lined out with Munster in the inter-provincial series of games, and enjoyed much success during a twelve-year career.

He made a winning debut in 1934, as a 6–3 to 3–2 defeat of Leinster gave Mackey his first Railway Cup medal.

After back-to-back defeats over the next two years, Mackey was captain of the Munster team in 1937. A 1–9 to 3–1 defeat of Leinster in the decider, gave Mackey a second Railway Cup medal. It was the first of four successive final defeats of Leinster, with Mackey playing a key role in all of these victories.

Five-in-a-row proved beyond Munster and, after a year of not playing any hurling, Mackey was back with Munster in 1943. A narrow 4–3 to 3–5 defeat of old rivals Leinster gave him a sixth Railway Cup medal.

Mackey finished off his inter-provincial career by winning back-to-back Railway Cup medals in 1945 and 1946, following respective defeats of Ulster and Connacht.

Recognition

As the first superstar of hurling, Mackey came to be regarded as one of the greatest players of all-time even during his playing days.

P.D. Mehigan, a contemporary Gaelic games journalist and historian, said of him: “…most elusive forward, and greatest playboy that ever handled ash, son of the great Tyler, schoolboys love him, hurling fans admire him; opposing backs fear him. A loveable man, full of the joy of life, still hurling well.”

Ned Maher, the former Tipperary goalkeeper of the 1890s said: “Mick Mackey was the greatest hurler ever and I saw them all.”

The arrival of Christy Ring as a hurling force brought a new challenger for pole position in the pantheon of hurling greats. Clare hurling legend Jimmy Smyth offered his view on the rivalry between Ring and Mackey:”With Mick Mackey, I saw him playing, but not at his best. A lot of people I met back in Clare always reckoned that Mackey was the best. But, you can’t decide. They were totally different people, personality-wise and hurling-wise.

Former Wexford All-Ireland winner Billy Rackard wrote: “When it comes to selecting the greatest exponent the game has ever seen, measured opinion sees one name out of reach – above all others. That name is Christy Ring of Cork. The nearest challenger is seen to be Mick Mackey of Limerick.”

In 1961 Mackey was presented with the Caltex Hall of Fame award for being the outstanding personality in hurling of all-time. That same year he was chosen in the half-forward line when journalist P.D. Mehigan picked “the best men of my time”.

Two years after his death, Mackey received the ultimate honour during the GAA’s centenary year in 1984 when he was chosen at centre-forward on the Hurling Team of the Century. He retained that position on the Hurling Team of the Millennium in 2000.

In 1988 the main covered stand in the Gaelic Grounds in Limerick was named the Mackey Stand in his honour, while the main playing field of the Ahane club is named Mackey Park. This is a tribute to the entire Mackey family for their contribution to the game.

In 2013 a bronze statue in memory of Mackey was unveiled in his native Castleconnell Around the same time the Munster Council turned down a Limerick motion to name the province’s senior hurling trophy in honour of Mackey.

Personal life

Mackey was born in Castleconnell, County Limerick on 12 July 1912, the eldest son to John “Tyler” and May Mackey (née Carroll). His younger siblings were John, Ester, Sadie, Paddy, Maureen, James “Todsie” and Breda.

Born into a family that was steeped in the traditions of the game of hurling, his grandfather and namesake, Michael Mackey, was involved in the promotion of Gaelic games even before the establishment of the Gaelic Athletic Association in 1884. He was captain of the Castleconnell team in the infancy of the association and was a member of the very first Limerick hurling team that played in the inaugural championship in 1887. His father, “Tyler” Mackey, ranked among the leading hurling personalities of the first two decades of the twentieth century. In a career that lasted from 1901 until 1917 he captained Limerick in the county’s unsuccessful 1910 All-Ireland title bid when Wexford were victorious by a single point.

Educated at Castleconnell National School, Mackey received no secondary schooling and subsequently joined the Electricity Supply Board where he spent forty-seven years as a van driver with the company at Ardnacrusha, County Clare. He also spent five years as a member of the Irish Army.

Mackey was married to Kathleen “Kitty” Kennedy (1914–2003) and the couple had five children: Paddy, Michael, Greg, Audrey and Ruth.

In declining health for some years, Mackey suffered a series of strokes towards the end of his life. He died on 13 September 1982.

Honours

Team

Ahane

Limerick Senior Hurling Championship (15): 1931, 1933, 1934, 1935, 1936, 1937, 1938, 1939, 1942, 1943, 1944, 1945, 1946, 1947, 1948

Limerick Senior Football Championship (5): 1935, 1936, 1937, 1938, 1939

Limerick

All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship (3): 1934, 1936 (c), 1940 (c)

Munster Senior Hurling Championship (5): 1933, 1934, 1935, 1936 (c), 1940 (c)

National Hurling League (5): 1933–34, 1934–35, 1935–36 (c), 1936–37, 1937–38

Munster

Railway Cup (8): 1934, 1937 (c), 1938, 1939, 1940, 1943, 1945, 1946

IndividualHonours

Hurling Team of the Millennium: Centre-forward

Hurling Team of the Century: Centre-forward

GAA All-Time All-Star Award: 1980

Caltex Hall of Fame Award: 1961

The 125 greatest stars of the GAA: No. 5

GAA Hall of Fame Inductee: 2013