The Still House at John’s Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

The Still House at John’s Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

-

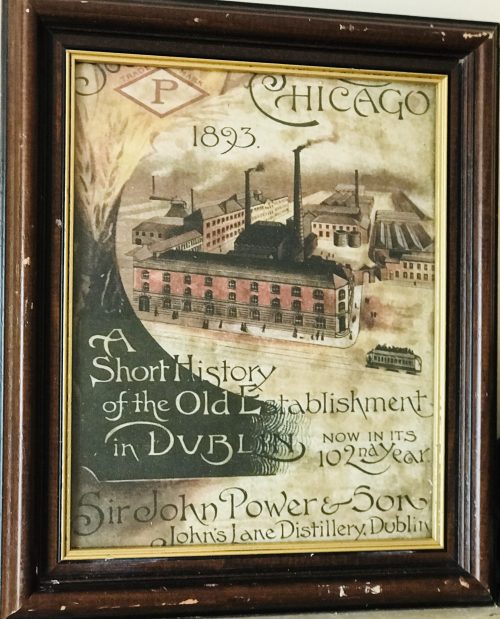

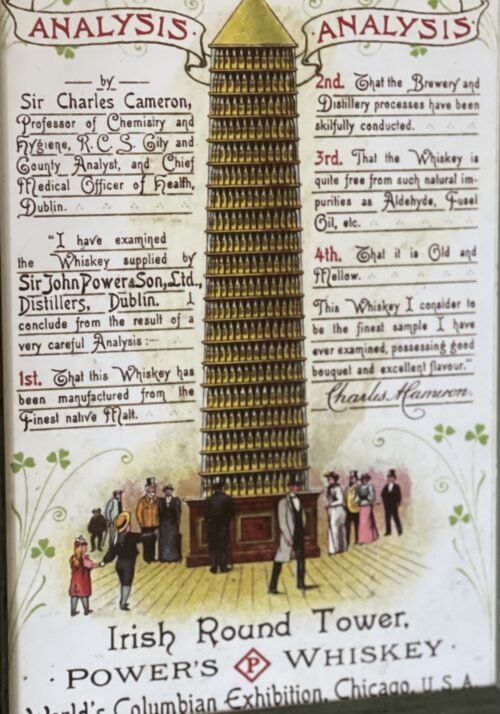

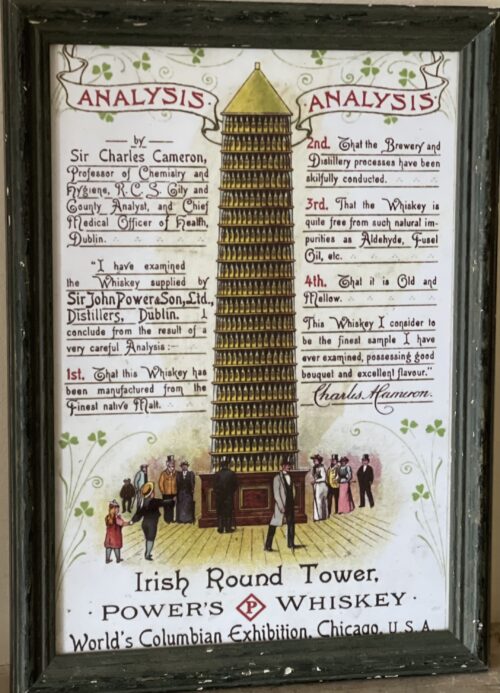

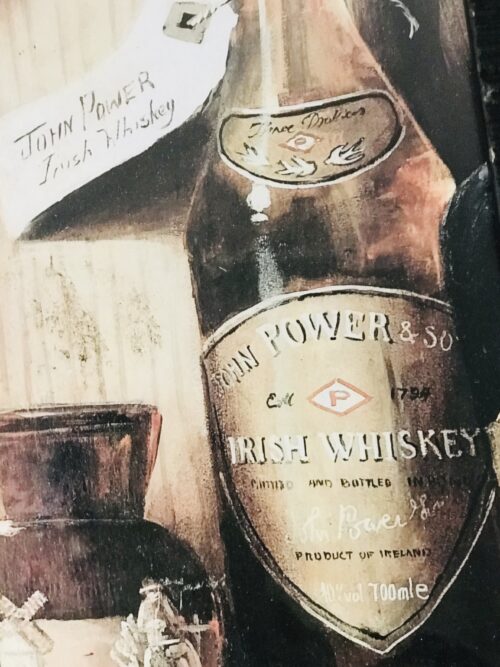

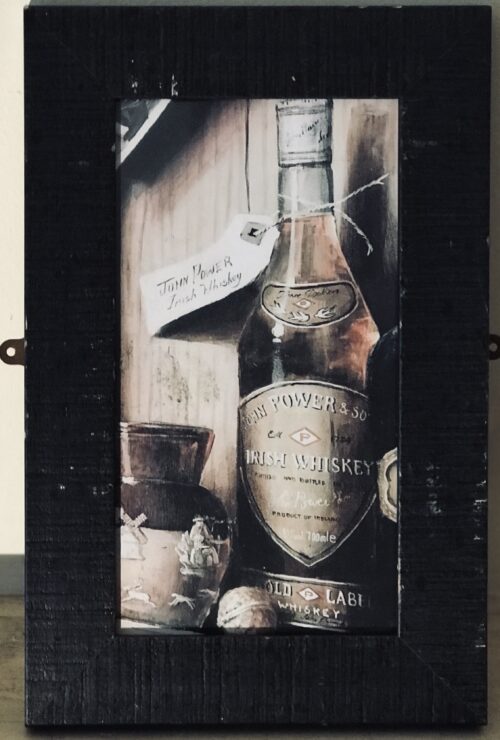

34cm x 27cm Dublin A beautiful souvenir Powers Whiskey print advertising the company's participation at the 1893 World Fair held in Chicago to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492.The fair was an influential social and cultural event and had a profound effect on architecture,sanitation,the Arts,Chicago's self image and American Industrial optimism .Powers Whiskey itself was established in 1792 before moving to Johns Lane in 1822 and then expanding its ranks and production levels rapidly to become one of the most impressive architectural sights in Victorian Dublin-an overhead view of which is depicted in this beautiful print. In 1791 James Power, an innkeeper from Dublin, established a small distillery at his public house at 109 Thomas St., Dublin. The distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son,and had moved to a new premises at John’s Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O’Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the “Big Four”) came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John’s Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as “about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere”. At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:”The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels.” The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power’s Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John’s Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John’s Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John’s Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery’s pot stills were saved and now located in the college’s Red Square.

34cm x 27cm Dublin A beautiful souvenir Powers Whiskey print advertising the company's participation at the 1893 World Fair held in Chicago to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492.The fair was an influential social and cultural event and had a profound effect on architecture,sanitation,the Arts,Chicago's self image and American Industrial optimism .Powers Whiskey itself was established in 1792 before moving to Johns Lane in 1822 and then expanding its ranks and production levels rapidly to become one of the most impressive architectural sights in Victorian Dublin-an overhead view of which is depicted in this beautiful print. In 1791 James Power, an innkeeper from Dublin, established a small distillery at his public house at 109 Thomas St., Dublin. The distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son,and had moved to a new premises at John’s Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O’Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the “Big Four”) came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John’s Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as “about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere”. At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:”The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels.” The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power’s Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John’s Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John’s Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John’s Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery’s pot stills were saved and now located in the college’s Red Square. The Still House at John’s Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

The Still House at John’s Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

-

34cm x 27cm Dublin A beautiful souvenir Powers Whiskey print advertising the company's participation at the 1893 World Fair held in Chicago to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492.The fair was an influential social and cultural event and had a profound effect on architecture,sanitation,the Arts,Chicago's self image and American Industrial optimism .Powers Whiskey itself was established in 1792 before moving to Johns Lane in 1822 and then expanding its ranks and production levels rapidly to become one of the most impressive architectural sights in Victorian Dublin-an overhead view of which is depicted in this beautiful print. In 1791 James Power, an innkeeper from Dublin, established a small distillery at his public house at 109 Thomas St., Dublin. The distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son,and had moved to a new premises at John’s Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O’Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the “Big Four”) came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John’s Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as “about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere”. At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:”The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels.” The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power’s Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John’s Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John’s Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John’s Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery’s pot stills were saved and now located in the college’s Red Square.

34cm x 27cm Dublin A beautiful souvenir Powers Whiskey print advertising the company's participation at the 1893 World Fair held in Chicago to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492.The fair was an influential social and cultural event and had a profound effect on architecture,sanitation,the Arts,Chicago's self image and American Industrial optimism .Powers Whiskey itself was established in 1792 before moving to Johns Lane in 1822 and then expanding its ranks and production levels rapidly to become one of the most impressive architectural sights in Victorian Dublin-an overhead view of which is depicted in this beautiful print. In 1791 James Power, an innkeeper from Dublin, established a small distillery at his public house at 109 Thomas St., Dublin. The distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son,and had moved to a new premises at John’s Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O’Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the “Big Four”) came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John’s Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as “about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere”. At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:”The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels.” The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power’s Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John’s Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John’s Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John’s Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery’s pot stills were saved and now located in the college’s Red Square. The Still House at John’s Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

The Still House at John’s Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

-

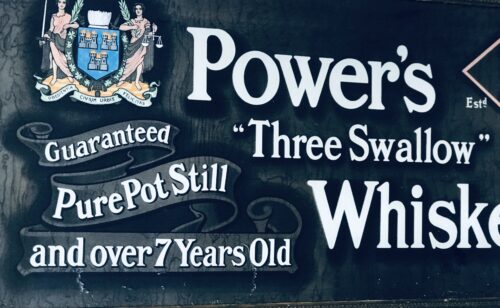

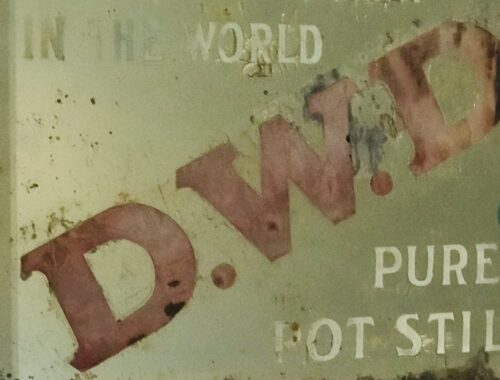

40cm x 80cm. Dublin The original distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son,and had moved to a new premises at John’s Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O’Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the “Big Four”) came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John’s Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as “about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere”. At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:”The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels.” The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power’s Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John’s Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John’s Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John’s Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery’s pot stills were saved and now located in the college’s Red Square. Origins: Co Waterford Dimensions :40cm x 77cm

40cm x 80cm. Dublin The original distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son,and had moved to a new premises at John’s Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O’Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the “Big Four”) came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John’s Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as “about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere”. At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:”The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels.” The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power’s Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John’s Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John’s Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John’s Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery’s pot stills were saved and now located in the college’s Red Square. Origins: Co Waterford Dimensions :40cm x 77cm The Still House at John’s Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

The Still House at John’s Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

-

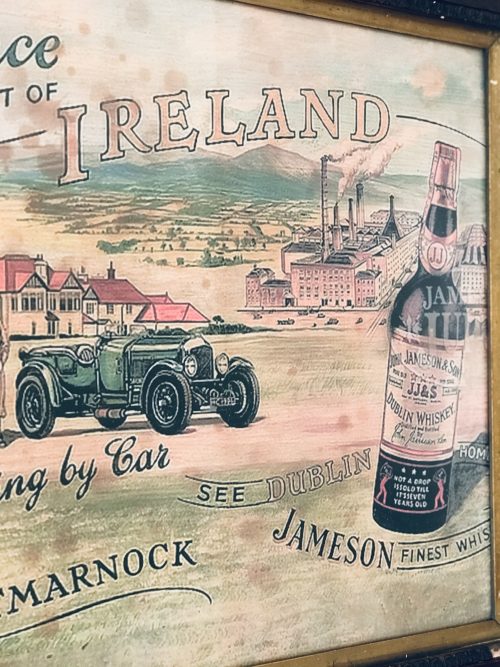

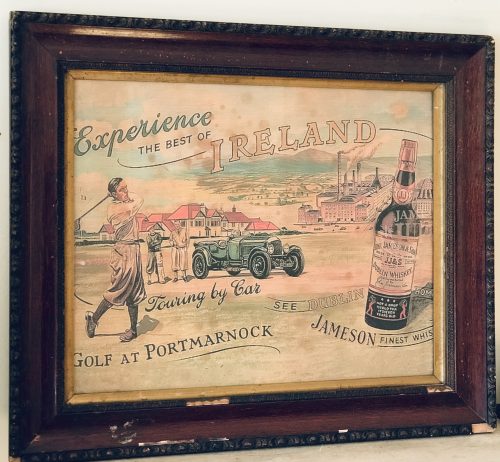

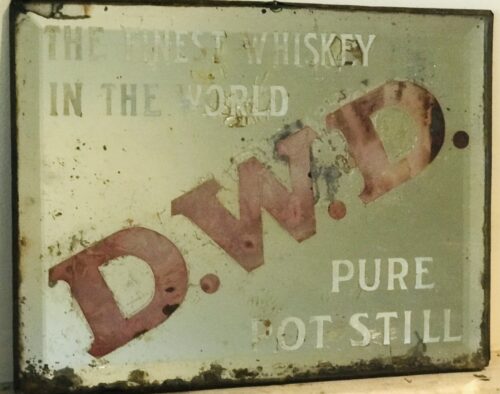

35cm x 25cm Dublin In 1791 James Power, an innkeeper from Dublin, established a small distillery at his public house at 109 Thomas St., Dublin. The distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son,and had moved to a new premises at John’s Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O’Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the “Big Four”) came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John’s Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as “about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere”. At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:”The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels.” The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power’s Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John’s Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John’s Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John’s Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery’s pot stills were saved and now located in the college’s Red Square.

35cm x 25cm Dublin In 1791 James Power, an innkeeper from Dublin, established a small distillery at his public house at 109 Thomas St., Dublin. The distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son,and had moved to a new premises at John’s Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O’Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the “Big Four”) came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John’s Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as “about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere”. At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:”The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels.” The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power’s Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John’s Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John’s Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John’s Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery’s pot stills were saved and now located in the college’s Red Square. The Still House at John’s Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

The Still House at John’s Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

-

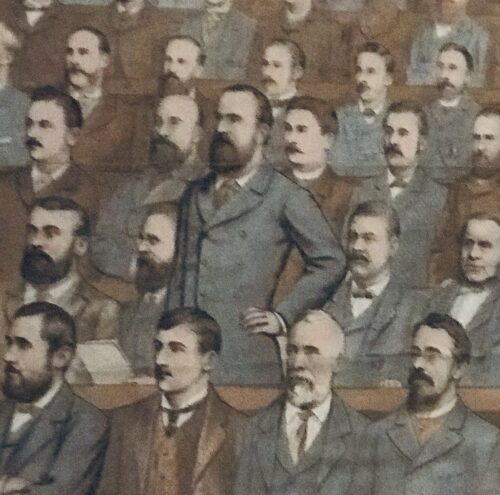

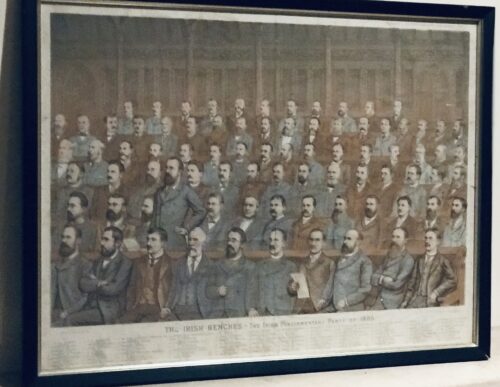

Extremely rare,interesting print of the Irish Benches of the Irish Parliamentary Party in the House of Commons in 1885,with all members identified by name and number. Gort Co Galway 45 cm x 60cm The Irish Parliamentary Party or more commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nationalist Members of Parliament (MPs) elected to the House of Commons at Westminster within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland up until 1918. Its central objectives were legislative independence for Ireland and land reform. Its constitutional movement was instrumental in laying the groundwork for Irish self-government through three Irish Home Rule bills.Instrumental to the party's rise and fall was the iconic statesman,Charles Stewart Parnell.

Extremely rare,interesting print of the Irish Benches of the Irish Parliamentary Party in the House of Commons in 1885,with all members identified by name and number. Gort Co Galway 45 cm x 60cm The Irish Parliamentary Party or more commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nationalist Members of Parliament (MPs) elected to the House of Commons at Westminster within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland up until 1918. Its central objectives were legislative independence for Ireland and land reform. Its constitutional movement was instrumental in laying the groundwork for Irish self-government through three Irish Home Rule bills.Instrumental to the party's rise and fall was the iconic statesman,Charles Stewart Parnell. -

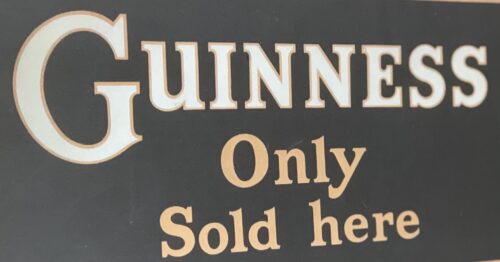

Quite hard to find Guinness Porter advert with suitably distressed appearance. Dimensions : 32cm x 40cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm

Quite hard to find Guinness Porter advert with suitably distressed appearance. Dimensions : 32cm x 40cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm -

Quite hard to find Guinness Porter on Draught advert with suitably distressed appearance. Dimensions : 32cm x 40cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm