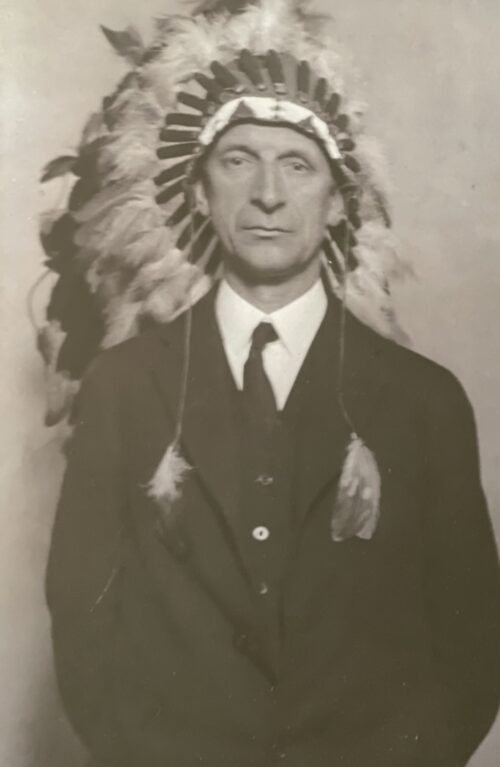

struggle for independence, this month marks the 100-year anniversary of an important moment in Irish-US relations.

In June 1919, Éamon de Valera arrived in the United States for what was to be an 18-month visit. He had recently escaped from Lincoln jail in England in sensational fashion, after a duplicate key was smuggled into the jail in a cake and he escaped dressed as a woman.

A few months later he was a stowaway aboard the SS Lapland from Liverpool bound for America.

De Valera’s plan was to secure recognition for the emerging Irish nation, tap into the huge Irish-American community for funds, and to pressurise the US government to take a stance on Irish independence. Playing on his mind was the upcoming Versailles conference where the nascent League of Nations was preparing to guarantee “existing international borders” – a provision that would imply Ireland remaining within the United Kingdom.

De Valera also had a challenge in winning over President Woodrow Wilson, who was less than sympathetic to Ireland’s cause.

De Valera’s interest in America was of course personal. He was born in New York in 1882 and his US citizenship was one of the reasons he was spared execution after the 1916 rising.

At first Dev kept a low profile in America. Though he was greeted by Harry Boland and others when he docked in New York, he first went to Philadelphia and stayed with Joseph McGarrity, the Tyrone-born leader of Clan na Gael and a well-known figure in Irish America. He also quietly paid a visit to his mother in Rochester, upstate New York.

De Valera’s first major engagement was on June 23rd when he was unveiled to the American public at a press conference in the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York. Crowds thronged the streets around the hotel, and De Valera proclaimed: “I am in America as the official head of the Republic established by the will of the Irish people in accordance with the principle of self-determination.”

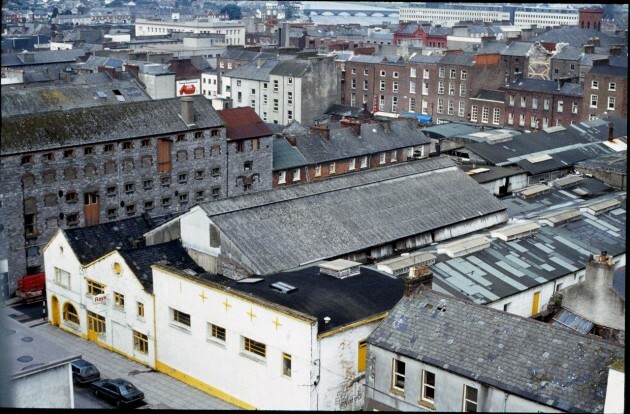

O'Mara's bacon factory, Roches Street, Limerick.Source: Courtesy of Tony Punch

Joe Hayes started working in a bacon factory in 1962, aged 16 years old. He worked with his dad, and later on with his two sons until the factory closed in 1986.

“When the factory closed, a group of us got our own little unit, we rented it, and produced our own sausages, puddings and things.”

It was a huge part of Limerick’s social scene: four generations of Joe’s family worked in bacon factories, with uncles, sisters, brothers, sons and cousins all working in the factory at one time or another:

“If one factory was caic, you wouldn’t have a problem getting a job in the other one.

O'Mara's bacon factory, Roches Street, Limerick.Source: Courtesy of Tony Punch

Joe Hayes started working in a bacon factory in 1962, aged 16 years old. He worked with his dad, and later on with his two sons until the factory closed in 1986.

“When the factory closed, a group of us got our own little unit, we rented it, and produced our own sausages, puddings and things.”

It was a huge part of Limerick’s social scene: four generations of Joe’s family worked in bacon factories, with uncles, sisters, brothers, sons and cousins all working in the factory at one time or another:

“If one factory was caic, you wouldn’t have a problem getting a job in the other one.

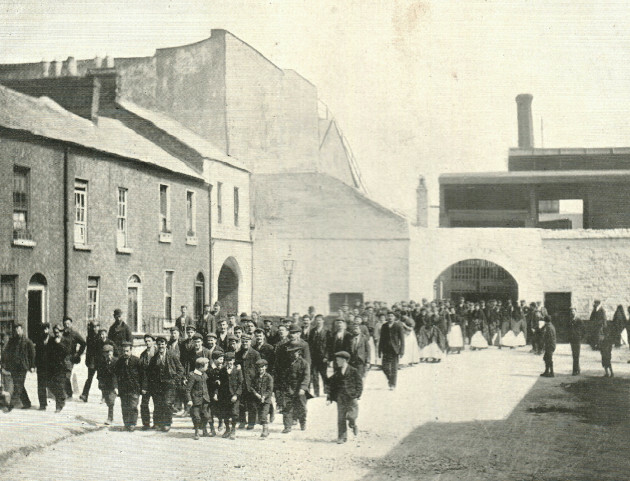

Leaving Mattersons at dinner hour.Source: Limerick Diocesan Archives

And he doesn’t mince his word when talking about the work they did.

“They brought the pigs in, we killed the pigs, and prepared the bacon: that’s the way it was in the bacon factories.” When asked about if there were ever animal cruelty protests, he laughs at the idea.

Leaving Mattersons at dinner hour.Source: Limerick Diocesan Archives

And he doesn’t mince his word when talking about the work they did.

“They brought the pigs in, we killed the pigs, and prepared the bacon: that’s the way it was in the bacon factories.” When asked about if there were ever animal cruelty protests, he laughs at the idea.

They started at 8am and finished at 5.30 working a 40 hour week when the factory closed in 1986, but despite their work, the people who worked in factories often couldn’t afford to buy the expensive cuts of meat.People still eat sausages and bacon – where do they think they come from?

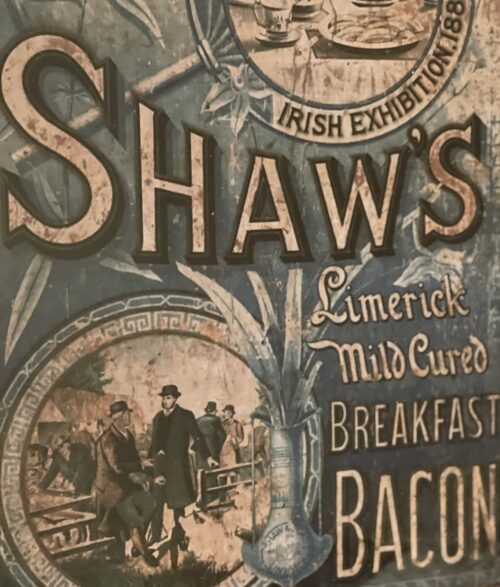

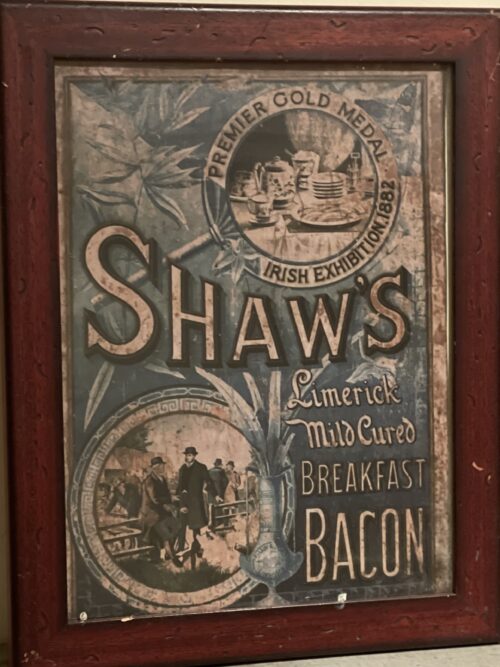

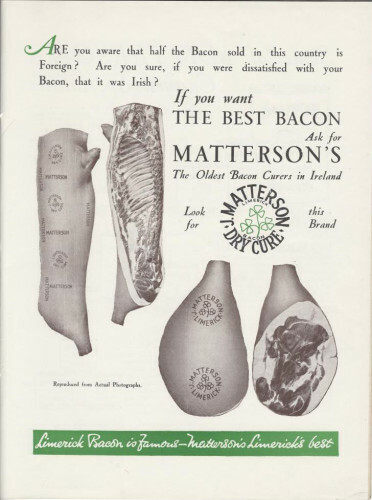

Matterson's advertisement for cuts of meat.Source: Limerick Archives

After the expensive cuts were prepared, the offal, the spare ribs, the pigs’ heads would go to the poorer people. “The blood was used to make the pudding, the packet, the tripe was made off the belly. Everything was used off the pig, and it fed Limerick city.”

It was a way of life down in Limerick, so when the factories closed, thousands of people working in a bacon factories were out of jobs, and thousands of families were affected.

But it wasn’t the competition from big supermarkets that did it – it was free trade. The Danes, the French, the Dutch all started exporting their products here, and Limerick factories didn’t have the money to export to compete.

Matterson's advertisement for cuts of meat.Source: Limerick Archives

After the expensive cuts were prepared, the offal, the spare ribs, the pigs’ heads would go to the poorer people. “The blood was used to make the pudding, the packet, the tripe was made off the belly. Everything was used off the pig, and it fed Limerick city.”

It was a way of life down in Limerick, so when the factories closed, thousands of people working in a bacon factories were out of jobs, and thousands of families were affected.

But it wasn’t the competition from big supermarkets that did it – it was free trade. The Danes, the French, the Dutch all started exporting their products here, and Limerick factories didn’t have the money to export to compete.

Source: National Library of Ireland

“Michael O’Mara’s funeral was this week – he was the last of the bacon factory managers.” says Joe. “After the Limerick factory closed, he tried doing different bits and pieces, but nothing worked out for him, so he worked in a factory for a couple of years before retiring.”

Joe Hayes himself is retired now, and when he buys his meat he gets it in a supermarket.

“Meat is meat,” he says.”But if I see the tricolour flag, I’ll still buy it even if it’s dearer.”

Pigtown - A History of Limerick’s Bacon Industry by Ruth Guiry is co-edited by Dr Maura Cronin and Jacqui Hayes.

Source: National Library of Ireland

“Michael O’Mara’s funeral was this week – he was the last of the bacon factory managers.” says Joe. “After the Limerick factory closed, he tried doing different bits and pieces, but nothing worked out for him, so he worked in a factory for a couple of years before retiring.”

Joe Hayes himself is retired now, and when he buys his meat he gets it in a supermarket.

“Meat is meat,” he says.”But if I see the tricolour flag, I’ll still buy it even if it’s dearer.”

Pigtown - A History of Limerick’s Bacon Industry by Ruth Guiry is co-edited by Dr Maura Cronin and Jacqui Hayes.