-

62cm x 62cm approx A real rarity here in the octagonal shape of a vintage Ireland Inland Waterways Cast-iron Sign denoting the river Shannon & Limerick.This most unusual find has been carefully restored and repainted and will make a most suitable exhibit for the most discerning Irish bar with Limerick /River Shannon affiliations.Please contact us directly at irishpubemporium@gmail.com or at 00353 878393200 to discuss.

62cm x 62cm approx A real rarity here in the octagonal shape of a vintage Ireland Inland Waterways Cast-iron Sign denoting the river Shannon & Limerick.This most unusual find has been carefully restored and repainted and will make a most suitable exhibit for the most discerning Irish bar with Limerick /River Shannon affiliations.Please contact us directly at irishpubemporium@gmail.com or at 00353 878393200 to discuss. -

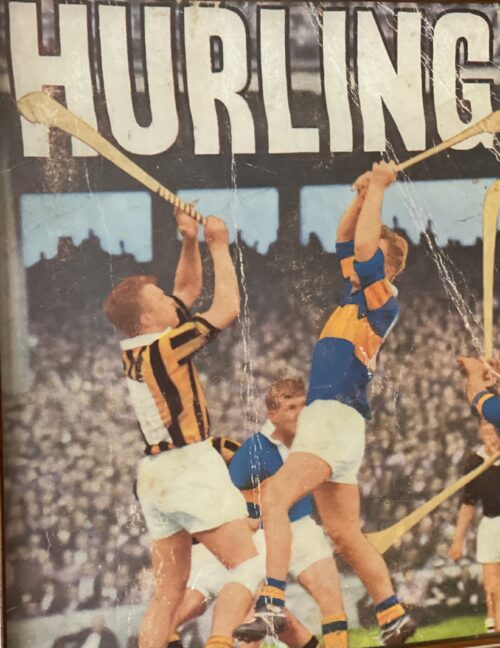

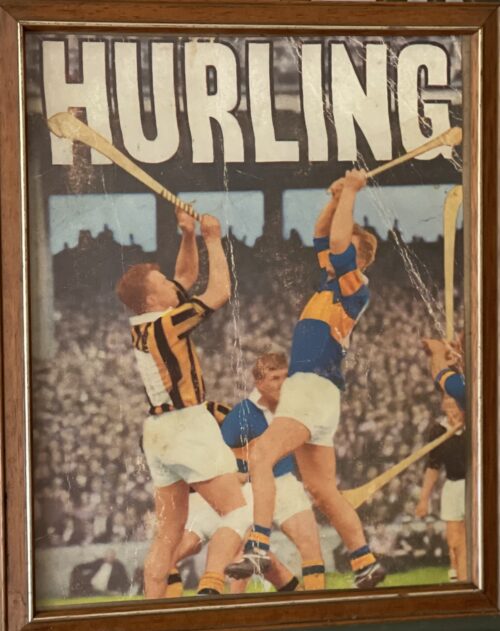

40cm x 34cm Hurling (Irish: iománaíocht, iomáint) is an outdoor team game of ancient Gaelic Irish origin, played by men. One of Ireland's native Gaelic games, it shares a number of features with Gaelic football, such as the field and goals, the number of players, and much terminology. There is a similar game for women called camogie (camógaíocht). It shares a common Gaelic root. The objective of the game is for players to use an ash wood stick called a hurley (in Irish a camán, pronounced /ˈkæmən/or /kəˈmɔːn/) to hit a small ball called a sliotar /ˈʃlɪtər/ between the opponents' goalposts either over the crossbar for one point, or under the crossbar into a net guarded by a goalkeeper for three points. The sliotar can be caught in the hand and carried for not more than four steps, struck in the air, or struck on the ground with the hurley. It can be kicked, or slapped with an open hand (the hand pass) for short-range passing. A player who wants to carry the ball for more than four steps has to bounce or balance the sliotar on the end of the stick, and the ball can only be handled twice while in the player’s possession. Provided that a player has at least one foot on the ground, a player may make a shoulder-to-shoulder charge on an opponent who is in possession of the ball or is playing the ball or when both players are moving in the direction of the ball to play it. No protective padding is worn by players. A plastic protective helmet with a faceguard is mandatory for all age groups, including senior level, as of 2010. The game has been described as "a bastion of humility", with player names absent from jerseys and a player's number decided by his position on the field. Hurling is administered by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA). It is played throughout the world, and is popular among members of the Irish diaspora in North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Argentina, and South Korea. In many parts of Ireland, however, hurling is a fixture of life.It has featured regularly in art forms such as film, music and literature. The final of the All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship was listed in second place by CNN in its "10 sporting events you have to see live", after the Olympic Games and ahead of both the FIFA World Cup and UEFA European Championship.After covering the 1959 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final between Kilkenny and Waterford for BBC Television, English commentator Kenneth Wolstenholme was moved to describe hurling as his second favourite sport in the world after his first love, football.Alex Ferguson used footage of an All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship final in an attempt to motivate his players during his time as manager of Premier League football club Manchester United; the players winced at the standard of physicality and intensity in which the hurlers were engaged. In 2007, Forbes magazine described the media attention and population multiplication of Thurles town ahead of one of the game's annual provincial hurling finals as being "the rough equivalent of 30 million Americans watching a regional lacrosse game".Financial Times columnist Simon Kuper wrote after Stephen Bennett's performance in the 2020 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final that hurling was "the best sport ever and if the Irish had colonised the world, nobody would ever have heard of football" UNESCO lists hurling as an element of Intangible cultural heritage.

40cm x 34cm Hurling (Irish: iománaíocht, iomáint) is an outdoor team game of ancient Gaelic Irish origin, played by men. One of Ireland's native Gaelic games, it shares a number of features with Gaelic football, such as the field and goals, the number of players, and much terminology. There is a similar game for women called camogie (camógaíocht). It shares a common Gaelic root. The objective of the game is for players to use an ash wood stick called a hurley (in Irish a camán, pronounced /ˈkæmən/or /kəˈmɔːn/) to hit a small ball called a sliotar /ˈʃlɪtər/ between the opponents' goalposts either over the crossbar for one point, or under the crossbar into a net guarded by a goalkeeper for three points. The sliotar can be caught in the hand and carried for not more than four steps, struck in the air, or struck on the ground with the hurley. It can be kicked, or slapped with an open hand (the hand pass) for short-range passing. A player who wants to carry the ball for more than four steps has to bounce or balance the sliotar on the end of the stick, and the ball can only be handled twice while in the player’s possession. Provided that a player has at least one foot on the ground, a player may make a shoulder-to-shoulder charge on an opponent who is in possession of the ball or is playing the ball or when both players are moving in the direction of the ball to play it. No protective padding is worn by players. A plastic protective helmet with a faceguard is mandatory for all age groups, including senior level, as of 2010. The game has been described as "a bastion of humility", with player names absent from jerseys and a player's number decided by his position on the field. Hurling is administered by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA). It is played throughout the world, and is popular among members of the Irish diaspora in North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Argentina, and South Korea. In many parts of Ireland, however, hurling is a fixture of life.It has featured regularly in art forms such as film, music and literature. The final of the All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship was listed in second place by CNN in its "10 sporting events you have to see live", after the Olympic Games and ahead of both the FIFA World Cup and UEFA European Championship.After covering the 1959 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final between Kilkenny and Waterford for BBC Television, English commentator Kenneth Wolstenholme was moved to describe hurling as his second favourite sport in the world after his first love, football.Alex Ferguson used footage of an All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship final in an attempt to motivate his players during his time as manager of Premier League football club Manchester United; the players winced at the standard of physicality and intensity in which the hurlers were engaged. In 2007, Forbes magazine described the media attention and population multiplication of Thurles town ahead of one of the game's annual provincial hurling finals as being "the rough equivalent of 30 million Americans watching a regional lacrosse game".Financial Times columnist Simon Kuper wrote after Stephen Bennett's performance in the 2020 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final that hurling was "the best sport ever and if the Irish had colonised the world, nobody would ever have heard of football" UNESCO lists hurling as an element of Intangible cultural heritage. -

57cm x 70cm Co Tipperary

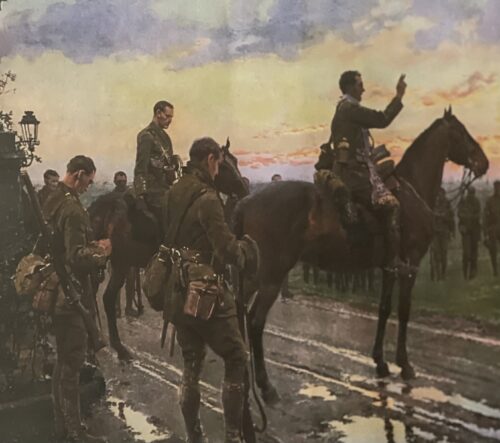

57cm x 70cm Co TipperaryThe most haunting and poignant image of Irish involvement in the first World War is at the centre of an unsolved art mystery.

The Last General Absolution of the Munsters at Rue du Bois – a painting long presumed lost – depicts soldiers of the Royal Munster Fusiliers regiment receiving “general absolution” from their chaplain on the eve of battle in May 1915. Most of them died within 24 hours.

The painting, by Italian-born war artist Fortunino Matania, became one of the most famous images of the war when prints of it were published in illustrated weekly newspapers.

Copies hung in houses & pubs throughout Ireland, and especially Munster, but, as Irish public opinion towards the war changed, the picture gradually disappeared from view.A copy still hangs in the famous pub Larkins of Garrykennedy Co Tipperary to this day.

Centenary commemorations of the first World War have prompted renewed interest in the whereabouts of the original painting among art and military historians.

A widely held theory that the painting was lost when archives were destroyed in a fire during the blitz of London in 1940 is “very much” doubted by English historian Lucinda Gosling, who is writing a book about the artist.

She told The Irish Times there was no definitive proof to confirm this theory and it was possible the original painting was still “out there”.

The painting could, conceivably, be in private hands or, more improbably, be lying forgotten or miscatalogued in a museum’s storage area. Matania’s work occasionally turns up at art auctions, but there has been no known or publicly-documented sighting of the original Munsters painting.

Ms Gosling described Matania as an artist “able to work at great speed, producing pictures that were unnervingly photographic in their realism”.

His pictures, she said, had “reached and influenced millions” and “he combined skill and artistry with a strong streak of journalistic tenacity”.

Wayside shrine

The painting is based on an event that took place on Saturday evening, May 8th, 1915.Soldiers from the Second Battalion, Royal Munster Fusiliers, commanded by Lieut-Col Victor Rickard, paused beside a wayside shrine near the village of Rue du Bois in northwest France. The following day, they were due to go into battle, in what became known as the Battle of Aubers Ridge.The painting is imbued with a sense of impending doom.

In Catholic canon law, a priest may grant general absolution of sin to a gathering of the faithful where there is imminent danger of death and no time for individual confessions.

The ritual was used on September 11th, 2001, in New York to grant general absolution to police officers and firefighters about to enter the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre.In the painting, the Irish chaplain Fr Francis Gleeson is shown blessing the men: “Misereatur vestri omnipotens Deus; et dimissis omnibus peccatis vestris, perducat vos Iesus Christus ad vitam aeternam” (May Almighty God have mercy on you, and having forgiven all your sins, may Jesus Christ bring you to life everlasting).

The men then sang the hymns Te Deum and Hail Glorious St Patrick.

The artist was not present at the scene but based his painting on a written account by Lieut- Col Rickard’s widow, Jessie, who is believed to have commissioned the painting in memory of her husband.

She had gathered eye-witness accounts from survivors and wrote: “There are many journeys and many stopping- places in the strange pilgrimage we call life, but there is no other such journey in the world as the journey up a road on the eve of battle, and no stopping- place more holy than a wayside shrine.”

She noted among the troops were “lads from Kerry and Cork, who, a year before, had never dreamed of marching in the ranks of the British army”.

After Fr Gleeson’s blessing, she wrote: “The regiment moved on, and darkness fell as the skirl of the Irish pipes broke out, playing a marching tune.“The Munsters were wild with enthusiasm; they were strong with the invincible strength of faith and high hope, for they had with them the vital conviction of success, the inspiration that scorns danger – which is the lasting heritage of the Irish; theirs still and theirs to remain when great armaments and armies and empires shall be swept away, because it is immovable as the eternal stars.”

Mown down

The following morning, Sunday May 9th, most of the Irish soldiers were mown down by German gunfire and shelling.

On a catastrophic day for the British army – over 11,000 casualties – the Royal Munster Fusiliers suffered dreadful losses. Exact estimates vary, but one account records 800 Munsters went into battle and only 200 assembled that evening.

Mrs Rickard concluded : “So the Munsters came back after their day’s work; they formed up again in the Rue du Bois, numbering 200 men and three officers. It seems almost superfluous to make any further comment.”

The Last General Absolution of the Munsters at Rue du Bois

The Painting

The Last General Absolution of the Munsters at Rue du Bois shows some of the hundreds of soldiers from the second battalion of the Royal Munster Fusiliers who gathered at a shrine near the village of Rue du Bois on the western front on Saturday, May 8th, 1915.

The image was published in the London illustrated weekly newspaper The Sphere in November 1916, and in 1917 in the Weekly Freeman’s, an Irish publication. There are copies of the print in various museums and in private ownership in Ireland and Britain.

The Artist

Fortunino Matania, (1881- 1963) was born in Naples and was a well-known artist and illustrator in Italy before moving to London in 1902. He worked for The Sphere – an illustrated weekly newspaper – and became famous for depicting the sinking of the Titanic in 1912.

He was an official war artist in the first World War and his graphic illustrations of trench warfare were highly renowned.

The Location

Rue du Bois is located near the village of Neuve Chapelle in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region of France close to the border with Belgium. According to the Royal Munster Fusiliers Association, the original shrine has long gone.

The Chaplain

Depicted on horseback, with hand raised granting general absolution, is Fr Francis Gleeson, a native of Templemore, Co Tipperary. He was ordained a priest in Maynooth in 1910 and volunteered to serve as a chaplain in the army at the outbreak of the war. He was assigned to the Royal Munster Fusiliers and served with distinction. He survived the war and returned to Ireland where he worked as priest in Dublin and died in 1959.

The Commanding Officer

Lieut-Col Victor Rickard, the other man on horseback, was born in Englandto an Irish father and English mother.

He was the commander of the battalion. He died in action the next day, aged 40.

The Patron

Lieut-Col Rickard’s widow Jessie, who is believed to have commissioned the painting, was the daughter of a Church of Ireland clergyman who spent her youth in Mitchelstown, Co Cork. She became a well-known novelist and published some 40 books.

After the war she converted to Catholicism under the guidance of another former chaplain in the British army in the first World War – Fr Joseph Leonard, who later befriended Jackie Kennedy.

Mrs Rickard died at Montenotte, Cork, in 1963, aged 86.

-

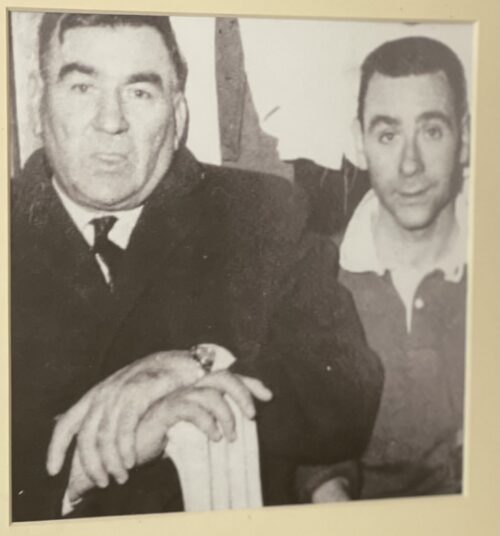

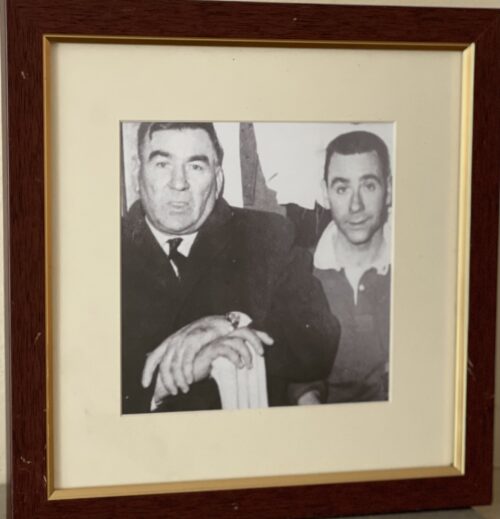

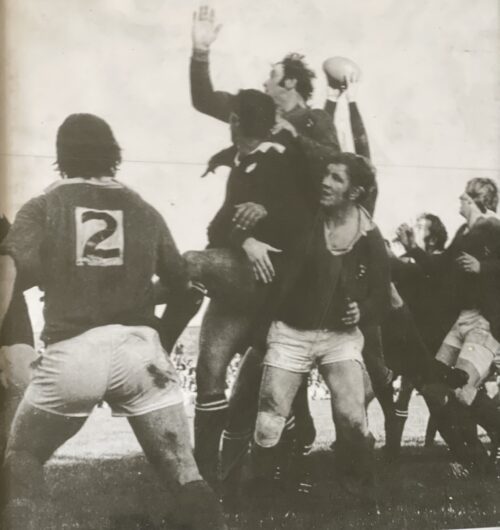

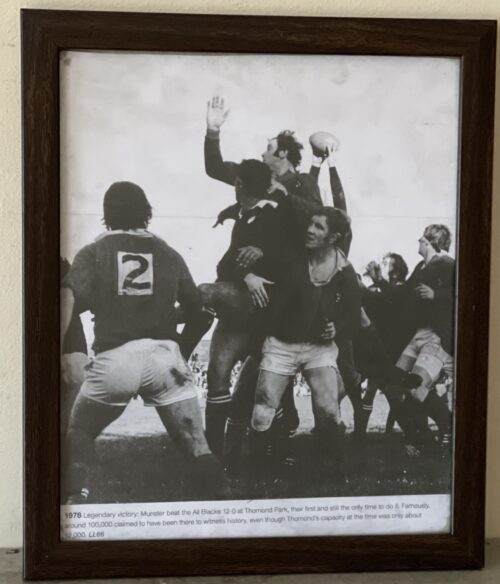

There are many chapters in Munster’s storied rugby journey but pride of place remains the game against the otherwise unbeaten New Zealanders on October 31, 1978. 40cm x 30cm There were some mighty matches between the Kiwis and Munster, most notably at the Mardyke in 1954 when the tourists edged home by 6-3 and again by the same margin at Thomond Park in 1963 while the teams also played a 3-3 draw at Musgrave Park in 1973. During that time, they resisted the best that Ireland, Ulster and Leinster (admittedly with fewer opportunities) could throw at them so this country was still waiting for any team to put one over on the All Blacks when Graham Mourie’s men arrived in Limerick on October 31st, 1978. There is always hope but in truth Munster supporters had little else to encourage them as the fateful day dawned. Whereas the New Zealanders had disposed of Cambridge University, Cardiff, West Wales and London Counties with comparative ease, Munster’s preparations had been confined to a couple of games in London where their level of performance, to put it mildly, was a long way short of what would be required to enjoy even a degree of respectability against the All Blacks. They were hammered by Middlesex County and scraped a draw with London Irish. Ever before those two games, things hadn’t been going according to plan. Tom Kiernan had coached Munster for three seasons in the mid-70s before being appointed Branch President, a role he duly completed at the end of the 1977/78 season. However, when coach Des Barry resigned for personal reasons, Munster turned once again to Kiernan. Being the great Munster man that he was and remains, Tom was happy to oblige although as an extremely shrewd observer of the game, one also suspected that he spotted something special in this group of players that had escaped most peoples’ attention. He refused to be dismayed by what he saw in the games in London, instead regarding them as crucial in the build-up to the All Blacks encounter. He was, in fact, ahead of his time, as he laid his hands on video footage of the All Blacks games, something unheard of back in those days, nor was he averse to the idea of making changes in key positions. A major case in point was the introduction of London Irish loose-head prop Les White of whom little was known in Munster rugby circles but who convinced the coaching team he was the ideal man to fill a troublesome position. Kiernan was also being confronted by many other difficult issues. The team he envisaged taking the field against the tourists was composed of six players (Larry Moloney, Seamus Dennison, Gerry McLoughlin, Pat Whelan, Brendan Foley and Colm Tucker) based in Limerick, four (Greg Barrett, Jimmy Bowen, Moss Finn and Christy Cantillon) in Cork, four more (Donal Canniffe, Tony Ward, Moss Keane and Donal Spring) in Dublin and Les White who, according to Keane, “hailed from somewhere in England, at that time nobody knew where”. Always bearing in mind that the game then was totally amateur and these guys worked for a living, for most people it would have been impossible to bring them all together on a regular basis for six weeks before the match. But the level of respect for Kiernan was so immense that the group would have walked on the proverbial bed of nails for him if he so requested. So they turned up every Wednesday in Fermoy — a kind of halfway house for the guys travelling from three different locations and over appreciable distances. Those sessions helped to forge a wonderful team spirit. After all, guys who had been slogging away at work only a short few hours previously would hardly make that kind of sacrifice unless they meant business. October 31, 1978 dawned wet and windy, prompting hope among the faithful that the conditions would suit Munster who could indulge in their traditional approach sometimes described rather vulgarly as “boot, bite and bollock” and, who knows, with the fanatical Thomond Park crowd cheering them on, anything could happen. Ironically, though, the wind and rain had given way to a clear, blue sky and altogether perfect conditions in good time for the kick-off. Surely, now, that was Munster’s last hope gone — but that didn’t deter more than 12,000 fans from making their way to Thomond Park and somehow finding a spot to view the action. The vantage points included hundreds seated on the 20-foot high boundary wall, others perched on the towering trees immediately outside the ground and some even watched from the windows of houses at the Ballynanty end that have since been demolished. The atmosphere was absolutely electric as the teams took the field, the All Blacks performed the Haka and the Welsh referee Corris Thomas got things under way. The first few skirmishes saw the teams sizing each other up before an incident that was to be recorded in song and story occurred, described here — with just the slightest touch of hyperbole! — by Terry McLean in his book ‘Mourie’s All Blacks’. “In only the fifth minute, Seamus Dennison, him the fellow that bore the number 13 jersey in the centre, was knocked down in a tackle. He came from the Garryowen club which might explain his subsequent actions — to join that club, so it has been said, one must walk barefooted over broken glass, charge naked through searing fires, run the severest gauntlets and, as a final test of manhood, prepare with unfaltering gaze to make a catch of the highest ball ever kicked while aware that at least eight thundering members of your own team are about to knock you down, trample all over you and into the bargain hiss nasty words at you because you forgot to cry out ‘Mark’. Moss Keane recalled the incident: “It was the hardest tackle I have ever seen and lifted the whole team. That was the moment we knew we could win the game.” Kiernan also acknowledged the importance of “The Tackle”.Many years on, Stuart Wilson vividly recalled the Dennison tackles and spoke about them in remarkable detail and with commendable honesty: “The move involved me coming in from the blind side wing and it had been working very well on tour. It was a workable move and it was paying off so we just kept rolling it out. Against Munster, the gap opened up brilliantly as it was supposed to except that there was this little guy called Seamus Dennison sitting there in front of me. “He just basically smacked the living daylights out of me. I dusted myself off and thought, I don’t want to have to do that again. Ten minutes later, we called the same move again thinking we’d change it slightly but, no, it didn’t work and I got hammered again.” The game was 11 minutes old when the most famous try in the history of Munster rugby was scored. Tom Kiernan recalled: “It came from a great piece of anticipation by Bowen who in the first place had to run around his man to get to Ward’s kick ahead. He then beat two men and when finally tackled, managed to keep his balance and deliver the ball to Cantillon who went on to score. All of this was evidence of sharpness on Bowen’s part.” Very soon it would be 9-0. In the first five minutes, a towering garryowen by skipper Canniffe had exposed the vulnerability of the New Zealand rearguard under the high ball. They were to be examined once or twice more but it was from a long range but badly struck penalty attempt by Ward that full-back Brian McKechnie knocked on some 15 yards from his line and close to where Cantillon had touched down a few minutes earlier. You could sense White, Whelan, McLoughlin and co in the front five of the Munster scrum smacking their lips as they settled for the scrum. A quick, straight put-in by Canniffe, a well controlled heel, a smart pass by the scrum-half to Ward and the inevitability of a drop goal. And that’s exactly what happened. The All Blacks enjoyed the majority of forward possession but the harder they tried, the more they fell into the trap set by the wily Kiernan and so brilliantly carried out by every member of the Munster team. The tourists might have edged the line-out contest through Andy Haden and Frank Oliver but scrum-half Mark Donaldson endured a miserable afternoon as the Munster forwards poured through and buried him in the Thomond Park turf. As the minutes passed and the All Blacks became more and more unsure as to what to try next, the Thomond Park hordes chanted “Munster-Munster–Munster” to an ever increasing crescendo until with 12 minutes to go, the noise levels reached deafening proportions. And then ... a deep, probing kick by Ward put Wilson under further pressure. Eventually, he stumbled over the ball as it crossed the line and nervously conceded a five-metre scrum. The Munster heel was disrupted but the ruck was won, Tucker gained possession and slipped a lovely little pass to Ward whose gifted feet and speed of thought enabled him in a twinkle to drop a goal although surrounded by a swarm of black jerseys. So the game entered its final 10 minutes with the All Blacks needing three scores to win and, of course, that was never going to happen. Munster knew this, so, too, did the All Blacks. Stu Wilson admitted as much as he explained his part in Wardy’s second drop goal: “Tony Ward banged it down, it bounced a little bit, jigged here, jigged there, and I stumbled, fell over, and all of a sudden the heat was on me. They were good chasers. A kick is a kick — but if you have lots of good chasers on it, they make bad kicks look good. I looked up and realised — I’m not going to run out of here so I just dotted it down. I wasn’t going to run that ball back out at them because five of those mad guys were coming down the track at me and I’m thinking, I’m being hit by these guys all day and I’m looking after my body, thank you. Of course it was a five-yard scrum and Ward banged over another drop goal. That was it, there was the game”. The final whistle duly sounded with Munster 12 points ahead but the heroes of the hour still had to get off the field and reach the safety of the dressing room. Bodies were embraced, faces were kissed, backs were pummelled, you name it, the gauntlet had to be walked. Even the All Blacks seemed impressed with the sense of joy being released all about them. Andy Haden recalled “the sea of red supporters all over the pitch after the game, you could hardly get off for the wave of celebration that was going on. The whole of Thomond Park glowed in the warmth that someone had put one over on the Blacks.” Controversially, the All Blacks coach, Jack Gleeson (usually a man capable of accepting the good with the bad and who passed away of cancer within 12 months of the tour), in an unguarded (although possibly misunderstood) moment on the following day, let slip his innermost thoughts on the game. “We were up against a team of kamikaze tacklers,” he lamented. “We set out on this tour to play 15-man rugby but if teams were to adopt the Munster approach and do all they could to stop the All Blacks from playing an attacking game, then the tour and the game would suffer.” It was interpreted by the majority of observers as a rare piece of sour grapes from a group who had accepted the defeat in good spirit and it certainly did nothing to diminish Munster respect for the All Blacks and their proud rugby tradition.He said: “Tackling is as integral a part of rugby as is a majestic centre three-quarter break. There were two noteworthy tackles during the match by Seamus Dennison. He was injured in the first and I thought he might have to come off. But he repeated the tackle some minutes later.”“Jack’s comment was made in the context of the game and meant as a compliment,” Haden maintained. “Indeed, it was probably a little suggestion to his own side that perhaps we should imitate their efforts and emulate them in that department.” Tom Kiernan went along with this line of thought: “I thought he was actually paying a compliment to the Munster spirit. Kamikaze pilots were very brave men. That’s what I took out of that. I didn’t think it was a criticism of Munster.” And Stuart Wilson? “It was meant purely as a compliment. We had been travelling through the UK and winning all our games. We were playing a nice, open style. But we had never met a team that could get up in our faces and tackle us off the field. Every time you got the ball, you didn’t get one player tackling you, you got four. Kamikaze means people are willing to die for the cause and that was the way with every Munster man that day. Their strengths were that they were playing for Munster, that they had a home Thomond Park crowd and they took strength from the fact they were playing one of the best teams in the world.” You could rely on Terry McLean (famed New Zealand journalist) to be fair and sporting in his reaction to the Thomond Park defeat. Unlike Kiernan and Haden, he scorned Jack Gleeson’s “kamikaze” comment, stating that “it was a stern, severe criticism which wanted in fairness on two grounds. It did not sufficiently praise the spirit of Munster or the presence within the one team of 15 men who each emerged from the match much larger than life-size. Secondly, it was disingenuous or, more accurately, naive.” “Gleeson thought it sinful that Ward had not once passed the ball. It was worse, he said, that Munster had made aggressive defence the only arm of their attack. Now, what on earth, it could be asked, was Kiernan to do with his team? He held a fine hand with top trumps in Spring, Cantillon, Foley and Whelan in the forwards and Canniffe, Ward, Dennison, Bowen and Moloney in the backs. Tommy Kiernan wasn’t born yesterday. He played to the strength of his team and upon the suspected weaknesses of the All Blacks.” You could hardly be fairer than that – even if Graham Mourie himself in his 1983 autobiography wasn’t far behind when observing: “Munster were just too good. From the first time Stu Wilson was crashed to the ground as he entered the back line to the last time Mark Donaldson was thrown backwards as he ducked around the side of a maul. They were too good.” One of the nicest tributes of all came from a famous New Zealand photographer, Peter Bush. He covered numerous All Black tours, was close friends with most of their players and a canny one when it came to finding the ideal position from which to snap his pictures. He was the guy perched precariously on the pillars at the entrance to the pitch as the celebrations went on and which he described 20 years later in his book ‘Who Said It’s Only a Game?’And Tom Kiernan and Andy Haden, rugby standard bearers of which their respective countries were justifiably proud, saw things in a similar light.“With that, he flung his arms around me and dragged me with him into the shower. I finally managed to disentangle myself and killed the tape. I didn’t mind really because it had been a wonderful day.” Dimensions :47cm x 57cm“I climbed up on a gate at the end of the game to get this photo and in the middle of it all is Moss Keane, one of the great characters of Irish rugby, with an expression of absolute elation. The All Blacks lost 12-0 to a side that played with as much passion as I have ever seen on a rugby field. The great New Zealand prop Gary Knight said to me later: ‘We could have played them for a fortnight and we still wouldn’t have won’. I was doing a little radio piece after the game and got hold of Moss Keane and said ‘Moss, I wonder if ...’ and he said, ‘ho, ho, we beat you bastards’.

There are many chapters in Munster’s storied rugby journey but pride of place remains the game against the otherwise unbeaten New Zealanders on October 31, 1978. 40cm x 30cm There were some mighty matches between the Kiwis and Munster, most notably at the Mardyke in 1954 when the tourists edged home by 6-3 and again by the same margin at Thomond Park in 1963 while the teams also played a 3-3 draw at Musgrave Park in 1973. During that time, they resisted the best that Ireland, Ulster and Leinster (admittedly with fewer opportunities) could throw at them so this country was still waiting for any team to put one over on the All Blacks when Graham Mourie’s men arrived in Limerick on October 31st, 1978. There is always hope but in truth Munster supporters had little else to encourage them as the fateful day dawned. Whereas the New Zealanders had disposed of Cambridge University, Cardiff, West Wales and London Counties with comparative ease, Munster’s preparations had been confined to a couple of games in London where their level of performance, to put it mildly, was a long way short of what would be required to enjoy even a degree of respectability against the All Blacks. They were hammered by Middlesex County and scraped a draw with London Irish. Ever before those two games, things hadn’t been going according to plan. Tom Kiernan had coached Munster for three seasons in the mid-70s before being appointed Branch President, a role he duly completed at the end of the 1977/78 season. However, when coach Des Barry resigned for personal reasons, Munster turned once again to Kiernan. Being the great Munster man that he was and remains, Tom was happy to oblige although as an extremely shrewd observer of the game, one also suspected that he spotted something special in this group of players that had escaped most peoples’ attention. He refused to be dismayed by what he saw in the games in London, instead regarding them as crucial in the build-up to the All Blacks encounter. He was, in fact, ahead of his time, as he laid his hands on video footage of the All Blacks games, something unheard of back in those days, nor was he averse to the idea of making changes in key positions. A major case in point was the introduction of London Irish loose-head prop Les White of whom little was known in Munster rugby circles but who convinced the coaching team he was the ideal man to fill a troublesome position. Kiernan was also being confronted by many other difficult issues. The team he envisaged taking the field against the tourists was composed of six players (Larry Moloney, Seamus Dennison, Gerry McLoughlin, Pat Whelan, Brendan Foley and Colm Tucker) based in Limerick, four (Greg Barrett, Jimmy Bowen, Moss Finn and Christy Cantillon) in Cork, four more (Donal Canniffe, Tony Ward, Moss Keane and Donal Spring) in Dublin and Les White who, according to Keane, “hailed from somewhere in England, at that time nobody knew where”. Always bearing in mind that the game then was totally amateur and these guys worked for a living, for most people it would have been impossible to bring them all together on a regular basis for six weeks before the match. But the level of respect for Kiernan was so immense that the group would have walked on the proverbial bed of nails for him if he so requested. So they turned up every Wednesday in Fermoy — a kind of halfway house for the guys travelling from three different locations and over appreciable distances. Those sessions helped to forge a wonderful team spirit. After all, guys who had been slogging away at work only a short few hours previously would hardly make that kind of sacrifice unless they meant business. October 31, 1978 dawned wet and windy, prompting hope among the faithful that the conditions would suit Munster who could indulge in their traditional approach sometimes described rather vulgarly as “boot, bite and bollock” and, who knows, with the fanatical Thomond Park crowd cheering them on, anything could happen. Ironically, though, the wind and rain had given way to a clear, blue sky and altogether perfect conditions in good time for the kick-off. Surely, now, that was Munster’s last hope gone — but that didn’t deter more than 12,000 fans from making their way to Thomond Park and somehow finding a spot to view the action. The vantage points included hundreds seated on the 20-foot high boundary wall, others perched on the towering trees immediately outside the ground and some even watched from the windows of houses at the Ballynanty end that have since been demolished. The atmosphere was absolutely electric as the teams took the field, the All Blacks performed the Haka and the Welsh referee Corris Thomas got things under way. The first few skirmishes saw the teams sizing each other up before an incident that was to be recorded in song and story occurred, described here — with just the slightest touch of hyperbole! — by Terry McLean in his book ‘Mourie’s All Blacks’. “In only the fifth minute, Seamus Dennison, him the fellow that bore the number 13 jersey in the centre, was knocked down in a tackle. He came from the Garryowen club which might explain his subsequent actions — to join that club, so it has been said, one must walk barefooted over broken glass, charge naked through searing fires, run the severest gauntlets and, as a final test of manhood, prepare with unfaltering gaze to make a catch of the highest ball ever kicked while aware that at least eight thundering members of your own team are about to knock you down, trample all over you and into the bargain hiss nasty words at you because you forgot to cry out ‘Mark’. Moss Keane recalled the incident: “It was the hardest tackle I have ever seen and lifted the whole team. That was the moment we knew we could win the game.” Kiernan also acknowledged the importance of “The Tackle”.Many years on, Stuart Wilson vividly recalled the Dennison tackles and spoke about them in remarkable detail and with commendable honesty: “The move involved me coming in from the blind side wing and it had been working very well on tour. It was a workable move and it was paying off so we just kept rolling it out. Against Munster, the gap opened up brilliantly as it was supposed to except that there was this little guy called Seamus Dennison sitting there in front of me. “He just basically smacked the living daylights out of me. I dusted myself off and thought, I don’t want to have to do that again. Ten minutes later, we called the same move again thinking we’d change it slightly but, no, it didn’t work and I got hammered again.” The game was 11 minutes old when the most famous try in the history of Munster rugby was scored. Tom Kiernan recalled: “It came from a great piece of anticipation by Bowen who in the first place had to run around his man to get to Ward’s kick ahead. He then beat two men and when finally tackled, managed to keep his balance and deliver the ball to Cantillon who went on to score. All of this was evidence of sharpness on Bowen’s part.” Very soon it would be 9-0. In the first five minutes, a towering garryowen by skipper Canniffe had exposed the vulnerability of the New Zealand rearguard under the high ball. They were to be examined once or twice more but it was from a long range but badly struck penalty attempt by Ward that full-back Brian McKechnie knocked on some 15 yards from his line and close to where Cantillon had touched down a few minutes earlier. You could sense White, Whelan, McLoughlin and co in the front five of the Munster scrum smacking their lips as they settled for the scrum. A quick, straight put-in by Canniffe, a well controlled heel, a smart pass by the scrum-half to Ward and the inevitability of a drop goal. And that’s exactly what happened. The All Blacks enjoyed the majority of forward possession but the harder they tried, the more they fell into the trap set by the wily Kiernan and so brilliantly carried out by every member of the Munster team. The tourists might have edged the line-out contest through Andy Haden and Frank Oliver but scrum-half Mark Donaldson endured a miserable afternoon as the Munster forwards poured through and buried him in the Thomond Park turf. As the minutes passed and the All Blacks became more and more unsure as to what to try next, the Thomond Park hordes chanted “Munster-Munster–Munster” to an ever increasing crescendo until with 12 minutes to go, the noise levels reached deafening proportions. And then ... a deep, probing kick by Ward put Wilson under further pressure. Eventually, he stumbled over the ball as it crossed the line and nervously conceded a five-metre scrum. The Munster heel was disrupted but the ruck was won, Tucker gained possession and slipped a lovely little pass to Ward whose gifted feet and speed of thought enabled him in a twinkle to drop a goal although surrounded by a swarm of black jerseys. So the game entered its final 10 minutes with the All Blacks needing three scores to win and, of course, that was never going to happen. Munster knew this, so, too, did the All Blacks. Stu Wilson admitted as much as he explained his part in Wardy’s second drop goal: “Tony Ward banged it down, it bounced a little bit, jigged here, jigged there, and I stumbled, fell over, and all of a sudden the heat was on me. They were good chasers. A kick is a kick — but if you have lots of good chasers on it, they make bad kicks look good. I looked up and realised — I’m not going to run out of here so I just dotted it down. I wasn’t going to run that ball back out at them because five of those mad guys were coming down the track at me and I’m thinking, I’m being hit by these guys all day and I’m looking after my body, thank you. Of course it was a five-yard scrum and Ward banged over another drop goal. That was it, there was the game”. The final whistle duly sounded with Munster 12 points ahead but the heroes of the hour still had to get off the field and reach the safety of the dressing room. Bodies were embraced, faces were kissed, backs were pummelled, you name it, the gauntlet had to be walked. Even the All Blacks seemed impressed with the sense of joy being released all about them. Andy Haden recalled “the sea of red supporters all over the pitch after the game, you could hardly get off for the wave of celebration that was going on. The whole of Thomond Park glowed in the warmth that someone had put one over on the Blacks.” Controversially, the All Blacks coach, Jack Gleeson (usually a man capable of accepting the good with the bad and who passed away of cancer within 12 months of the tour), in an unguarded (although possibly misunderstood) moment on the following day, let slip his innermost thoughts on the game. “We were up against a team of kamikaze tacklers,” he lamented. “We set out on this tour to play 15-man rugby but if teams were to adopt the Munster approach and do all they could to stop the All Blacks from playing an attacking game, then the tour and the game would suffer.” It was interpreted by the majority of observers as a rare piece of sour grapes from a group who had accepted the defeat in good spirit and it certainly did nothing to diminish Munster respect for the All Blacks and their proud rugby tradition.He said: “Tackling is as integral a part of rugby as is a majestic centre three-quarter break. There were two noteworthy tackles during the match by Seamus Dennison. He was injured in the first and I thought he might have to come off. But he repeated the tackle some minutes later.”“Jack’s comment was made in the context of the game and meant as a compliment,” Haden maintained. “Indeed, it was probably a little suggestion to his own side that perhaps we should imitate their efforts and emulate them in that department.” Tom Kiernan went along with this line of thought: “I thought he was actually paying a compliment to the Munster spirit. Kamikaze pilots were very brave men. That’s what I took out of that. I didn’t think it was a criticism of Munster.” And Stuart Wilson? “It was meant purely as a compliment. We had been travelling through the UK and winning all our games. We were playing a nice, open style. But we had never met a team that could get up in our faces and tackle us off the field. Every time you got the ball, you didn’t get one player tackling you, you got four. Kamikaze means people are willing to die for the cause and that was the way with every Munster man that day. Their strengths were that they were playing for Munster, that they had a home Thomond Park crowd and they took strength from the fact they were playing one of the best teams in the world.” You could rely on Terry McLean (famed New Zealand journalist) to be fair and sporting in his reaction to the Thomond Park defeat. Unlike Kiernan and Haden, he scorned Jack Gleeson’s “kamikaze” comment, stating that “it was a stern, severe criticism which wanted in fairness on two grounds. It did not sufficiently praise the spirit of Munster or the presence within the one team of 15 men who each emerged from the match much larger than life-size. Secondly, it was disingenuous or, more accurately, naive.” “Gleeson thought it sinful that Ward had not once passed the ball. It was worse, he said, that Munster had made aggressive defence the only arm of their attack. Now, what on earth, it could be asked, was Kiernan to do with his team? He held a fine hand with top trumps in Spring, Cantillon, Foley and Whelan in the forwards and Canniffe, Ward, Dennison, Bowen and Moloney in the backs. Tommy Kiernan wasn’t born yesterday. He played to the strength of his team and upon the suspected weaknesses of the All Blacks.” You could hardly be fairer than that – even if Graham Mourie himself in his 1983 autobiography wasn’t far behind when observing: “Munster were just too good. From the first time Stu Wilson was crashed to the ground as he entered the back line to the last time Mark Donaldson was thrown backwards as he ducked around the side of a maul. They were too good.” One of the nicest tributes of all came from a famous New Zealand photographer, Peter Bush. He covered numerous All Black tours, was close friends with most of their players and a canny one when it came to finding the ideal position from which to snap his pictures. He was the guy perched precariously on the pillars at the entrance to the pitch as the celebrations went on and which he described 20 years later in his book ‘Who Said It’s Only a Game?’And Tom Kiernan and Andy Haden, rugby standard bearers of which their respective countries were justifiably proud, saw things in a similar light.“With that, he flung his arms around me and dragged me with him into the shower. I finally managed to disentangle myself and killed the tape. I didn’t mind really because it had been a wonderful day.” Dimensions :47cm x 57cm“I climbed up on a gate at the end of the game to get this photo and in the middle of it all is Moss Keane, one of the great characters of Irish rugby, with an expression of absolute elation. The All Blacks lost 12-0 to a side that played with as much passion as I have ever seen on a rugby field. The great New Zealand prop Gary Knight said to me later: ‘We could have played them for a fortnight and we still wouldn’t have won’. I was doing a little radio piece after the game and got hold of Moss Keane and said ‘Moss, I wonder if ...’ and he said, ‘ho, ho, we beat you bastards’. -

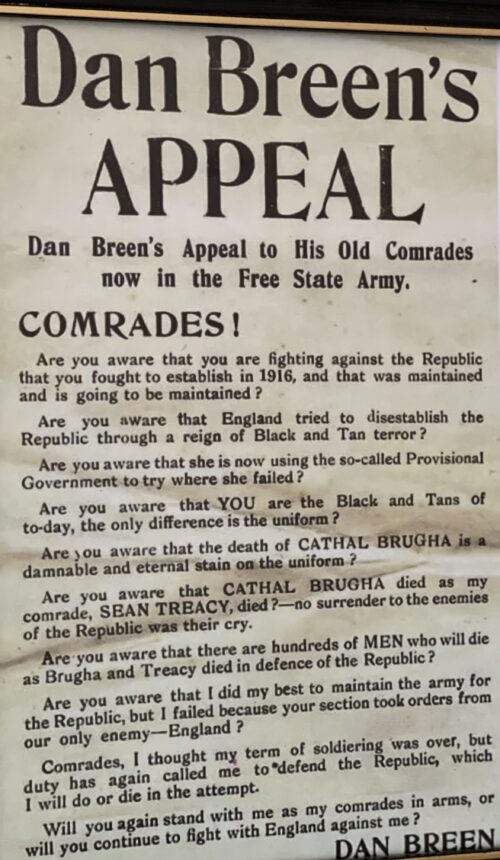

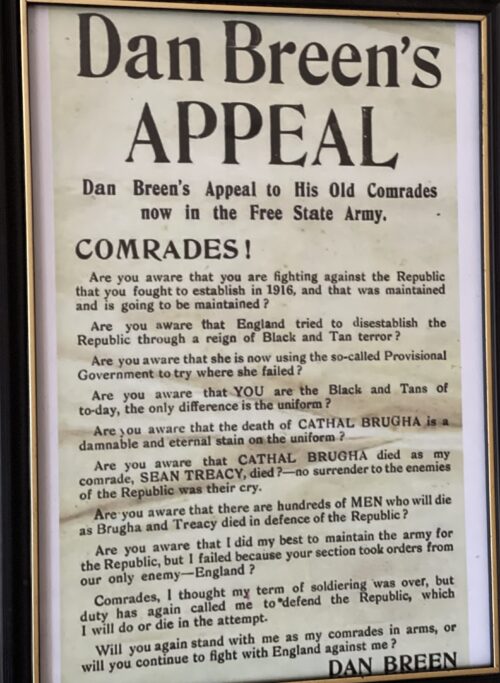

Daniel Breen (11 August 1894 – 27 December 1969) was a volunteer in the Irish Republican Armyduring the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War. In later years he was a Fianna Fáil politician.

Daniel Breen (11 August 1894 – 27 December 1969) was a volunteer in the Irish Republican Armyduring the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War. In later years he was a Fianna Fáil politician.Background

Dan Breen was born in Grange, Donohill parish, County Tipperary. His father died when Breen was six, leaving the family very poor. He was educated locally, before becoming a plasterer and later a linesman on the Great Southern Railways.Irish Revolutionary Period

War of Independence

Breen was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1912 and the Irish Volunteers in 1914. On 21 January 1919, the day the First Dáil met in Dublin, Breen—who described himself as "a soldier first and foremost"—took part in the Soloheadbeg Ambush.The ambush party of eight men, nominally led by Séumas Robinson, attacked two Royal Irish Constabulary men who were escorting explosives to a quarry. The two policemen, James McDonnell and Patrick O’Connell, were fatally shot during the incident. The ambush is considered to be the first incident of the Irish War of Independence. Breen later recalled:"...we took the action deliberately, having thought over the matter and talked it over between us. [Seán] Treacyhad stated to me that the only way of starting a war was to kill someone, and we wanted to start a war, so we intended to kill some of the police whom we looked upon as the foremost and most important branch of the enemy forces ... The only regret that we had following the ambush was that there were only two policemen in it, instead of the six we had expected..."

During the conflict, the British put a £1,000 price on Breen's head, which was later raised to £10,000.He quickly established himself as a leader within the Irish Republican Army (IRA). He was known for his courage. On 13 May 1919, he helped rescue his comrade Seán Hogan at gunpoint from a heavily guarded train at Knocklong station in County Limerick. Breen, who was wounded, remembered how the battalion was "vehemently denounced as a cold-blooded assassins" and roundly condemned by the Catholic Church. After the fight, Seán Treacy, Séumas Robinson and Breen met Michael Collins in Dublin, where they were told to escape from the area. They agreed they would "fight it out, of course". Breen and Treacy shot their way out through a British military cordon in the northern suburb of Drumcondra (Fernside). They escaped, only for Treacy to be killed the next day. Breen was shot at least four times, twice in the lung. The British reaction was to make Tipperary a 'Special Military Area', with curfews and travel permits. Volunteer GHQ authorised enterprising attacks on barracks. Richard Mulcahy noted that British policy had "pushed rather turbulent spirits such as Breen and Treacy into the Dublin area". The inculcation of the principles of guerrilla warfare was to become an essential part of all training. They joined Collins' Squad of assassins, later known as the Dublin Guard, when Tipperary became "too hot for them". and Dublin was the centre of the war. Breen was present in December 1919 at the ambush in Ashtown beside Phoenix Park in Dublin where Martin Savage was killed while trying to assassinate the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Viscount French. The IRA men hid behind hedges and a dungheap as the convoy of vehicles came past. They had been instructed to ignore the first car, but this contained their target, Lord French. Their roadblock failed as a policeman removed the horse and cart intended to stop the car. Breen rejected the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which made him, like many others, angry and embittered:I would never have handled a gun or fired a shot… to obtain this Treaty… writing on the second anniversary of Martin Savage's death, do you suppose that he sacrificed his life in attempting to kill one British Governor-General to make room for another British Governor-General?

Regarding the continued existence of Northern Ireland from 1922, and an inevitable further war to conquer it to create a united Ireland, Breen commented:- "To me, a united Ireland of two million people would be preferable to an Ireland of four and a half million divided into three or four factions".

Irish Civil War

Breen was elected to Dáil Éireann at the 1923 general election as a Republican anti-Treaty Teachta Dála (TD) for the Tipperary constituency.Following the Anglo-Irish Treaty, Breen joined the Anti-Treaty IRA in the Civil War, fighting against those of his former comrades in arms who supported the Treaty. He was arrested by the National Army of the Irish Free State and interned at Limerick Prison. He spent two months there before going on hunger strike for six days, followed by a thirst strike of six days. Breen was released after he signed a document pleading to desist from attacking the Free State. Breen wrote a best-selling account of his guerrilla days, My Fight for Irish Freedom, in 1924, later republished by Rena Dardis and Anvil Press.Politics

Fianna Fáil TD

Breen represented Tipperary from the Fourth Dáil in 1923 as a Republican with Éamon de Valera and Frank Aiken.He was the first anti-Treaty TD to take his seat, in 1927. Standing as an Independent Republican he was defeated in the June 1927 general election. Thereafter Breen travelled to the United States, where he opened a speakeasy. He returned to Ireland in 1932 following the death of his mother,and regained his seat as a member of Fianna Fáil in the Dáil at that year's general election. He represented his Tipperary constituency without a break until his retirement at the 1965 election.Political views

Breen supported the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War. During World War II, he was said to hold largely pro-Axis views, with admiration for Erwin Rommel.When the fascist political party Ailtirí na hAiséirghe failed to win any seats in the 1944 Irish general election, he remarked that he was sorry that the party had not done better, as he had studied their programme and found a lot to commend. In 1946, Breen became secretary of the Save the German Children Society. He attended the funeral of Nazi spy Hermann Gortz on 27 May 1947.Irish-American John S. Monagan visited Breen in 1948, and was surprised to see two pictures of Adolf Hitler, a medallion of Napoleon and a Telefunken radio. Breen told him "the revolution didn't work out," and "to get the government they have now, I wouldn't have lost a night's sleep." He also said that he fought for freedom, but not for democracy.In 1943, Breen sent his "congratulations to the Führer. May he live long to lead Europe on the road to peace, security and happiness". After the end of World War II in Europe, the German Legation in Dublin was taken over by diplomats from the USA in May 1945, and ".. they found a recent letter from Breen asking the German minister to forward his birthday wishes to the Führer, just days before Hitler committed suicide." Breen was co-chairman of the anti-Vietnam War organisation "Irish Voice on Vietnam".Personal life

Breen was married on 12 June 1921, during the War of Independence, to Brigid Malone, a Dublin Cumann na mBan woman and sister of Lieutenant Michael Malone who was killed in action at the Battle of Mount Street Bridge during the 1916 Rising. They had met in Dublin when she helped to nurse him while he was recovering from a bullet wound. Seán Hogan was best man, and the bride's sister Aine Malone was the bridesmaid. Photographs of the wedding celebrations taken by 5th Battalion intelligence officer Séan Sharkey are published in The Tipperary Third Brigade a photographic record. Breen was, at the time, one of the most wanted men in Ireland, and South Tipperary was under martial law, yet a large celebration was held. The wedding took place at Purcell's, "Glenagat House", New Inn, County Tipperary. Many of the key members of the Third Tipperary Brigade attended, including flying column leaders Dinny Lacey and Hogan. Breen was the brother in-law of Commandant Theobald Wolfe Tone FitzGerald, the painter of the Irish Republic Flag that flew over the GPO during the Easter Rising in 1916. The Breens had two children, Donal and Granya. Breen was an atheist.Death

Breen died in Dublin in 1969, aged 75, and was buried in Donohill, near his birthplace. His funeral was the largest seen in west Tipperary since that of his close friend and comrade-in-arms, Seán Treacy, at Kilfeacle in October 1920. An estimated attendance of 10,000 mourners assembled in the tiny hamlet, giving ample testimony to the esteem in which he was held. Breen was the subject of a 2007 biography, Dan Breen and the IRA by Joe Ambrose.In popular culture

Breen is mentioned in the Irish folk ballad "The Galtee Mountain Boy", along with Seán Moylan, Dinny Lacey, and Seán Hogan. The song, written by Patsy Halloran, recalls some of the travels of a "Flying column" from Tipperary as they fought during the Irish War of Independence, and later against the pro-Treaty side during the Irish Civil War. The trophy for the Tipperary Senior Hurling Championship is named after him. -

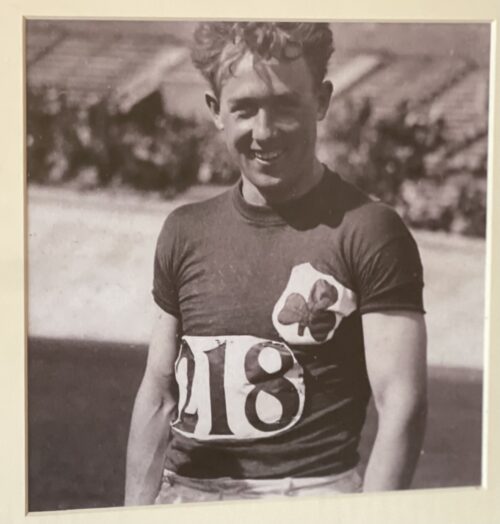

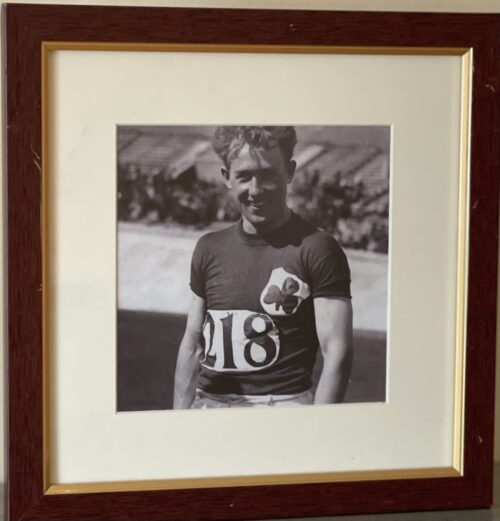

30cm x 30cm Patrick "Pat" O'Callaghan (28 January 1906 – 1 December 1991) was an Irish athlete and Olympic gold medallist. He was the first athlete from Ireland to win an Olympic medal under the Irish flag rather than the British. In sport he then became regarded as one of Ireland's greatest-ever athletes.

30cm x 30cm Patrick "Pat" O'Callaghan (28 January 1906 – 1 December 1991) was an Irish athlete and Olympic gold medallist. He was the first athlete from Ireland to win an Olympic medal under the Irish flag rather than the British. In sport he then became regarded as one of Ireland's greatest-ever athletes.Early and private life

Pat O'Callaghan was born in the townland of Knockaneroe, near Kanturk, County Cork, on 28 January 1906, the second of three sons born to Paddy O'Callaghan, a farmer, and Jane Healy. He began his education at the age of two at Derrygalun national school. O'Callaghan progressed to secondary school in Kanturk and at the age of fifteen he won a scholarship to the Patrician Academy in Mallow. During his year in the Patrician Academy he cycled the 32-mile round trip from Derrygalun every day and he never missed a class. O'Callaghan subsequently studied medicine at the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin. Following his graduation in 1926 he joined the Royal Air Force Medical Service. He returned to Ireland in 1928 and set up his own medical practice in Clonmel, County Tipperary where he worked until his retirement in 1984.O'Callaghan was also a renowned field sports practitioner, greyhound trainer and storyteller.Sporting career

Early sporting life

O’Callaghan was born into a family that had a huge interest in a variety of different sports. His uncle, Tim Vaughan, was a national sprint champion and played Gaelic football with Cork in 1893. O’Callaghan's eldest brother, Seán, also enjoyed football as well as winning a national 440 yards hurdles title, while his other brother, Con, was also regarded as a gifted runner, jumper and thrower. O’Callaghan's early sporting passions included hunting, poaching and Gaelic football. He was regarded as an excellent midfielder on the Banteer football team, while he also lined out with the Banteer hurling team. At university in Dublin O’Callaghan broadened his sporting experiences by joining the local senior rugby club. This was at a time when the Gaelic Athletic Association ‘ban’ forbade players of Gaelic games from playing "foreign sports". It was also in Dublin that O’Callaghan first developed an interest in hammer-throwing. In 1926, he returned to his native Duhallow where he set up a training regime in hammer-throwing. Here he fashioned his own hammer by boring a one-inch hole through a 16 lb shot and filling it with the ball-bearing core of a bicycle pedal. He also set up a throwing circle in a nearby field where he trained. In 1927, O’Callaghan returned to Dublin where he won that year's hammer championship with a throw of 142’ 3”. In 1928, he retained his national title with a throw of 162’ 6”, a win which allowed him to represent the Ireland at the forthcoming Olympic Games in Amsterdam. On the same day, O’Callaghan's brother, Con, won the shot put and the decathlon and also qualified for the Olympic Games. Between winning his national title and competing in the Olympic Games O’Callaghan improved his throwing distance by recording a distance of 166’ 11” at the Royal Ulster ConstabularySports in Belfast.1928 Olympic Games

In the summer of 1928, the three O’Callaghan brothers paid their own fares when travelling to the Olympic Games in Amsterdam. Pat O’Callaghan finished in sixth place in the preliminary round and started the final with a throw of 155’ 9”. This put him in third place behind Ossian Skiöld of Sweden, but ahead of Malcolm Nokes, the favourite from Great Britain. For his second throw, O’Callaghan used the Swede's own hammer and recorded a throw of 168’ 7”. This was 4’ more than Skoeld's throw and resulted in a first gold medal for O’Callaghan and for Ireland. The podium presentation was particularly emotional as it was the first time at an Olympic Games that the Irish tricolour was raised and Amhrán na bhFiann was played.Success in Ireland

After returning from the Olympic Games, O’Callaghan cemented his reputation as a great athlete with additional successes between 1929 and 1932. In the national championships of 1930 he won the hammer, shot-putt, 56 lbs without follow, 56 lbs over-the-bar, discus and high jump. In the summer of 1930, O’Callaghan took part in a two-day invitation event in Stockholm where Oissian Skoeld was expected to gain revenge on the Irishman for the defeat in Amsterdam. On the first day of the competition, Skoeld broke his own European record with his very first throw. O’Callaghan followed immediately and overtook him with his own first throw and breaking the new record. On the second day of the event both O’Callaghan and Skoeld were neck-and-neck, when the former, with his last throw, set a new European record of 178’ 8” to win.1932 Summer Olympics

By the time the 1932 Summer Olympics came around O’Callaghan was regularly throwing the hammer over 170 feet. The Irish team were much better organised on that occasion and the whole journey to Los Angeles was funded by a church-gate collection. Shortly before departing on the 6,000-mile boat and train journey across the Atlantic O’Callaghan collected a fifth hammer title at the national championships. On arrival in Los Angeles O’Callaghan's preparations of the defence of his title came unstuck. The surface of the hammer circle had always been of grass or clay and throwers wore field shoes with steel spikes set into the heel and sole for grip. In Los Angeles, however, a cinder surface was to be provided. The Olympic Committee of Ireland had failed to notify O’Callaghan of this change. Consequently, he came to the arena with three pairs of spiked shoes for a grass or clay surface and time did not permit a change of shoe. He wore his shortest spikes, but found that they caught in the hard gritty slab and impeded his crucial third turn. In spite of being severely impeded, he managed to qualify for the final stage of the competition with his third throw of 171’ 3”. While the final of the 400m hurdles was delayed, O’Callaghan hunted down a hacksaw and a file in the groundskeeper's shack and he cut off the spikes. O’Callaghan's second throw reached a distance of 176’ 11”, a result which allowed him to retain his Olympic title. It was Ireland's second gold medal of the day as Bob Tisdall had earlier won a gold medal in the 400m hurdles.Retirement

Due to the celebrations after the Olympic Games O’Callaghan didn't take part in the national athletic championships in Ireland in 1933. In spite of that he still worked hard on his training and he experimented with a fourth turn to set a new European record at 178’ 9”. By this stage O’Callaghan was rated as the top thrower in the world by the leading international sports journalists. In the early 1930s controversy raged between the British AAA and the National Athletic and Cycling Association of Ireland (NACAI). The British AAA claimed jurisdiction in Northern Ireland while the NACAI claimed jurisdiction over the entire island of Ireland regardless of political division. The controversy came to a head in the lead-up to the 1936 Summer Olympics when the IAAF finally disqualified the NACAI. O’Callaghan remained loyal to the NACAI, a decision which effectively brought an end to his international athletic career. No Irish team travelled to the 1936 Olympic Games, however O’Callaghan travelled to Berlin as a private spectator. After Berlin, O’Callaghan's international career was over. He declined to join the new Irish Amateur Athletics Union (IAAU) or subsequent IOC recognised Amateur Athletics Union of Eire (AAUE) and continued to compete under NACAI rules. At Fermoy in 1937 he threw 195’ 4” – more than seven feet ahead of the world record set by his old friend Paddy 'Chicken' Ryan in 1913. This record, however, was not ratified by the AAUE or the IAAF. In retirement O’Callaghan remained interested in athletics. He travelled to every Olympic Games up until 1988 and enjoyed fishing and poaching in Clonmel. He died on 1 December 1991.Legacy

O'Callaghan was the flag bearer for Ireland at the 1932 Olympics. In 1960, he became the first person to receive the Texaco Hall of Fame Award. He was made a Freeman of Clonmel in 1984, and was honorary president of Commercials Gaelic Football Club. The Dr. Pat O'Callaghan Sports Complex at Cashel Rd, Clonmel which is the home of Clonmel Town Football Club is named after him, and in January 2007 his statue was raised in Banteer, County Cork. -

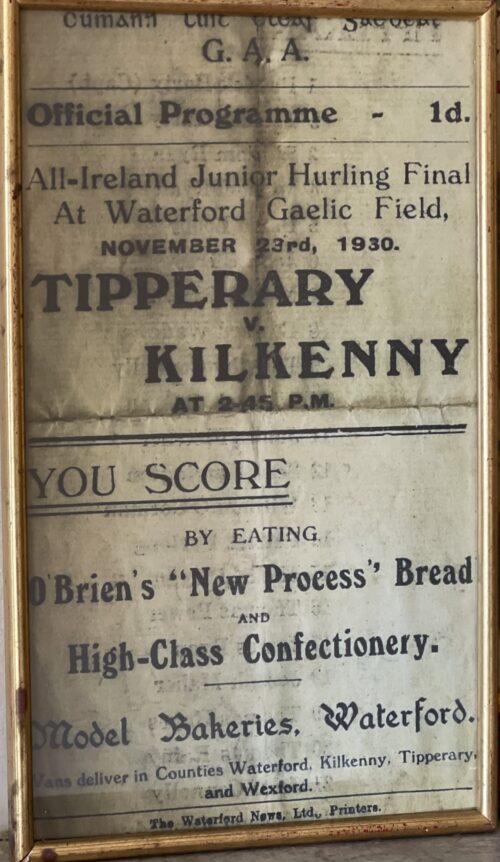

40cm x 23cm Thurles Co Tipperary The All-Ireland Junior Hurling Championship was a hurling competition organized by the Gaelic Athletic Association in Ireland. The competition was originally contested by the second teams of the strong counties, and the first teams of the weaker counties. In the years from 1961 to 1973 and from 1997 until now, the strong counties have competed for the All-Ireland Intermediate Hurling Championship instead. The competition was then restricted to the weaker counties. The competition was discontinued after 2004 as these counties now compete for the Nicky Rackard Cup instead. From 1974 to 1982, the original format of the competition was abandoned, and the competition was incorporated in Division 3 of the National Hurling League. The original format, including the strong hurling counties was re-introduced in 1983. 1930 – TIPPERARY: Paddy Harty (Captain), Tom Harty, Willie Ryan, Tim Connolly, Mick McGann, Martin Browne, Ned Wade, Tom Ryan, Jack Dwyer, Mick Ryan, Dan Looby, Pat Furlong, Bill O’Gorman, Joe Fletcher, Sean Harrington.

40cm x 23cm Thurles Co Tipperary The All-Ireland Junior Hurling Championship was a hurling competition organized by the Gaelic Athletic Association in Ireland. The competition was originally contested by the second teams of the strong counties, and the first teams of the weaker counties. In the years from 1961 to 1973 and from 1997 until now, the strong counties have competed for the All-Ireland Intermediate Hurling Championship instead. The competition was then restricted to the weaker counties. The competition was discontinued after 2004 as these counties now compete for the Nicky Rackard Cup instead. From 1974 to 1982, the original format of the competition was abandoned, and the competition was incorporated in Division 3 of the National Hurling League. The original format, including the strong hurling counties was re-introduced in 1983. 1930 – TIPPERARY: Paddy Harty (Captain), Tom Harty, Willie Ryan, Tim Connolly, Mick McGann, Martin Browne, Ned Wade, Tom Ryan, Jack Dwyer, Mick Ryan, Dan Looby, Pat Furlong, Bill O’Gorman, Joe Fletcher, Sean Harrington. -

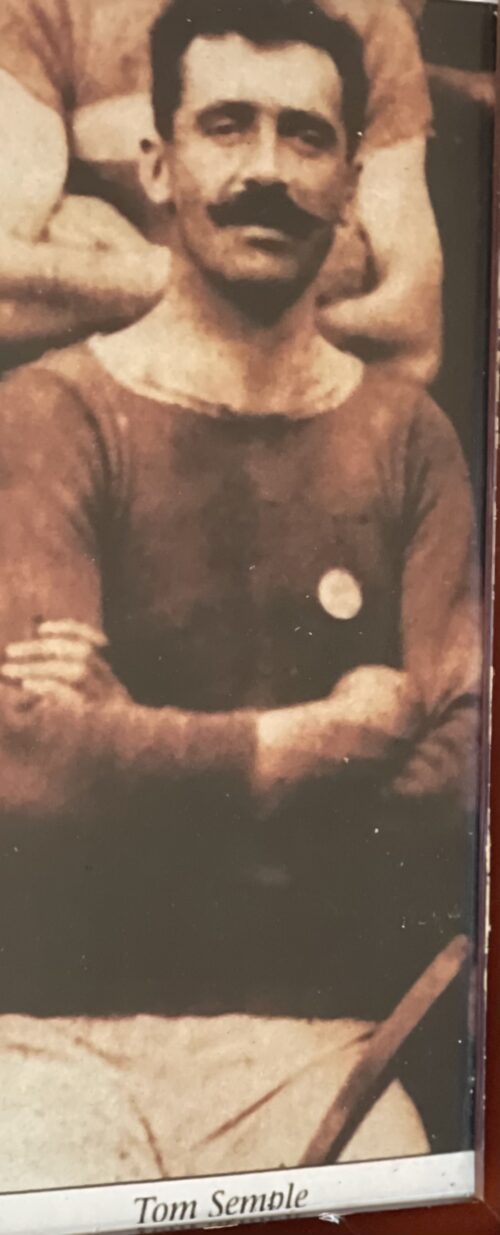

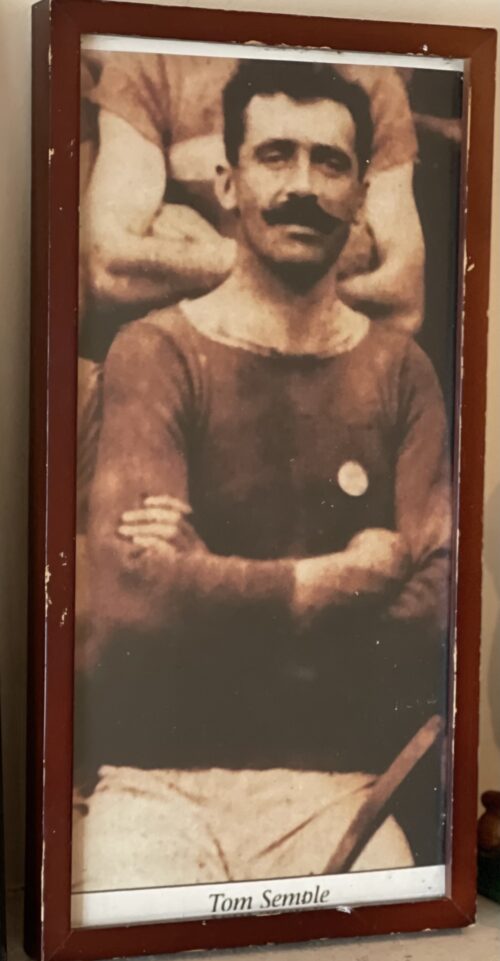

Great portrait of Tipperary Hurling Legend Tom Semple of Thurles 47cm x 24cm Thurles Co Tipperary Thomas Semple (8 April 1879 – 11 April 1943) was an Irish hurler who played as a half-forward for the Tipperary senior team. Semple joined the panel during the 1897 championship and eventually became a regular member of the starting seventeen until his retirement after the 1909 championship. During that time he won three All-Ireland medals and four Munster medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on one occasion, Semple captained the team to the All-Ireland title in 1906 and in 1908. At club level Semple was a six-time county club championship medalist with Thurles. Semple played his club hurling with the local club in Thurles, the precursor to the famous Sarsfield's club. He rose through the club and served as captain of the team for almost a decade. In 1904 Semple won his first championship medal following a walkover from Lahorna De Wets. Thurles failed to retain their title, however, the team returned to the championship decider once again in 1906. A 4-11 to 3-6 defeat of Lahorna De Wets gave Semple his second championship medal as captain. It was the first of four successive championships for Thurles as subsequent defeats of Lahorna De Wets, Glengoole and Racecourse/Grangemockler brought Semple's medal tally to five. Five-in-a-row proved beyond Thurles, however, Semple's team reached the final for the sixth time in eight seasons in 1911. A 4-5 to 1-0 trouncing of Toomevara gave Semple his sixth and final championship medal as captain.

Great portrait of Tipperary Hurling Legend Tom Semple of Thurles 47cm x 24cm Thurles Co Tipperary Thomas Semple (8 April 1879 – 11 April 1943) was an Irish hurler who played as a half-forward for the Tipperary senior team. Semple joined the panel during the 1897 championship and eventually became a regular member of the starting seventeen until his retirement after the 1909 championship. During that time he won three All-Ireland medals and four Munster medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on one occasion, Semple captained the team to the All-Ireland title in 1906 and in 1908. At club level Semple was a six-time county club championship medalist with Thurles. Semple played his club hurling with the local club in Thurles, the precursor to the famous Sarsfield's club. He rose through the club and served as captain of the team for almost a decade. In 1904 Semple won his first championship medal following a walkover from Lahorna De Wets. Thurles failed to retain their title, however, the team returned to the championship decider once again in 1906. A 4-11 to 3-6 defeat of Lahorna De Wets gave Semple his second championship medal as captain. It was the first of four successive championships for Thurles as subsequent defeats of Lahorna De Wets, Glengoole and Racecourse/Grangemockler brought Semple's medal tally to five. Five-in-a-row proved beyond Thurles, however, Semple's team reached the final for the sixth time in eight seasons in 1911. A 4-5 to 1-0 trouncing of Toomevara gave Semple his sixth and final championship medal as captain.Inter-county

Semple's skill quickly brought him to the attention of the Tipperary senior hurling selectors. After briefly joining the team in 1897, he had to wait until 1900 to become a regular member of the starting seventeen. That year a 6-11 to 1-9 trouncing of Kerry gave him his first Munster medal.Tipp later narrowly defeated Kilkenny in the All-Ireland semi-final before trouncing Galway in the "home" All-Ireland final. This was not the end of the championship campaign because, for the first year ever, the "home" finalists had to take on London in the All-Ireland decider. The game was a close affair with both sides level at five points with eight minutes to go. London then took the lead; however, they later conceded a free. Tipp's Mikey Maher stepped up, took the free and a forward charge carried the sliotar over the line. Tipp scored another goal following a weak puck out and claimed a 2-5 to 0-6 victory.It was Semple's first All-Ireland medal. Cork dominated the provincial championship for the next five years; however, Tipp bounced back in 1906. That year Semple was captain for the first time as Tipp foiled Cork's bid for an unprecedented sixth Munster title in-a-row. The score line of 3-4 to 0-9 gave Semple a second Munster medal. Tipp trounced Galway by 7-14 to 0-2 on their next outing, setting up an All-Ireland final meeting with Dublin. Semple's side got off to a bad start with Dublin's Bill Leonard scoring a goal after just five seconds of play. Tipp fought back with Paddy Riordan giving an exceptional display of hurling and capturing most of his team's scores. Ironically, eleven members of the Dublin team hailed from Tipperary. The final score of 3-16 to 3-8 gave victory to Tipperary and gave Semple a second All-Ireland medal. Tipp lost their provincial crown in 1907, however, they reached the Munster final again in 1908. Semple was captain of the side again that year as his team received a walkover from Kerry in the provincial decider. Another defeat of Galway in the penultimate game set up another All-Ireland final meeting with Dublin. That game ended in a 2-5 to 1-8 draw and a replay was staged several months later in Athy. Semple's team were much sharper on that occasion. A first-half goal by Hugh Shelly put Tipp well on their way. Two more goals by Tony Carew after the interval gave Tipp a 3-15 to 1-5 victory.It was Semple's third All-Ireland medal. 1909 saw Tipp defeat arch rivals Cork in the Munster final once again. A 2-10 to 1-6 victory gave Semple his fourth Munster medal. The subsequent All-Ireland final saw Tipp take on Kilkenny. The omens looked good for a Tipperary win. It was the county's ninth appearance in the championship decider and they had won the previous eight. All did not go to plan as this Kilkenny side cemented their reputation as the team of the decade. A 4-6 to 0-12 defeat gave victory to "the Cats" and a first final defeat to Tipperary. Semple retired from inter-county hurling following this defeat. Semple was born in Drombane, County Tipperary in 1879. He received a limited education at his local national school and, like many of his contemporaries, finding work was a difficult prospect. At the age of 16 Semple left his native area and moved to Thurles. Here he worked as a guardsman with the Great Southern & Western Railway. In retirement from playing Semple maintained a keen interest in Gaelic games. In 1910 he and others organised a committee which purchased the showgrounds in Thurles in an effort to develop a hurling playing field there. This later became known as Thurles Sportsfield and is regarded as one of the best surfaces for hurling in Ireland. In 1971 it was renamed Semple Stadium in his honour. The stadium is also lovingly referred to as Tom Semple's field. Semple also held the post of chairman of the Tipperary County Board and represented the Tipperary on the Munster Council and Central Council. He also served as treasurer of the latter organization. During the War of Independence Semple played an important role for Republicans. He organized dispatches via his position with the Great Southern & Western Railway in Thurles. Tom Semple died on 11 April 1943 Tipperary Hurling Team outside Clonmel railway station, August 26, 1910. Semple is in the centre of the middle row.

Tipperary Hurling Team outside Clonmel railway station, August 26, 1910. Semple is in the centre of the middle row. -

35cm x 50cm Limerick

35cm x 50cm Limerickloody Sunday, 21st November 1920

In 1920 the War of Independence was ongoing in Ireland.

On the morning of November 21st, an elite assassination unit known as ‘The Squad’ mounted an operation planned by Michael Collins, Director of Intelligence of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Their orders were clear – they were to take out the backbone of the British Intelligence network in Ireland, specifically a group of officers known as ‘The Cairo Gang’. The shootings took place in and around Dublin’s south inner city and resulted in fourteen deaths, including six intelligence agents and two members of the British Auxiliary Force. Later that afternoon, Dublin were scheduled to play Tipperary in a one-off challenge match at Croke Park, the proceeds of which were in aid of the Republican Prisoners Dependents Fund. Tensions were high in Dublin due to fears of a reprisal by Crown forces following the assassinations. Despite this a crowd of almost 10,000 gathered in Croke Park. Throw-in was scheduled for 2.45pm, but it did not start until 3.15pm as crowd congestion caused a delay.Eye-witness accounts suggest that five minutes after the throw-in an aeroplane flew over Croke Park. It circled the ground twice and shot a red flare - a signal to a mixed force of Royal Irish Constabulary (R.I.C.), Auxiliary Police and Military who then stormed into Croke Park and opened fire on the crowd. Amongst the spectators, there was a rush to all four exits, but the army stopped people from leaving the ground and this created a series of crushes around the stadium. Along the Cusack Stand side, hundreds of people braved the twenty-foot drop and jumped into the adjacent Belvedere Sports Grounds. The shooting lasted for less than two minutes. That afternoon in Croke Park, 14 people including one player (Michael Hogan from Tipperary), lost their lives. It is estimated that 60 – 100 people were injured. Dublin Team, Bloody Sunday 1920The names of those who died in Croke Park on Bloody Sunday 1920 were. James Burke, Jane Boyle, Daniel Carroll, Michael Feery, Michael Hogan, Thomas (Tom) Hogan, James Matthews, Patrick O’Dowd, Jerome O’Leary, William (Perry) Robinson, Tom Ryan, John William (Billy) Scott, James Teehan, Joseph Traynor. In 1925, the GAA's Central Council took the decision to name a stand in Croke Park after Michael Hogan. The 21st November 2020 marks one hundred years since the events of Bloody Sunday in Croke Park.

Dublin Team, Bloody Sunday 1920The names of those who died in Croke Park on Bloody Sunday 1920 were. James Burke, Jane Boyle, Daniel Carroll, Michael Feery, Michael Hogan, Thomas (Tom) Hogan, James Matthews, Patrick O’Dowd, Jerome O’Leary, William (Perry) Robinson, Tom Ryan, John William (Billy) Scott, James Teehan, Joseph Traynor. In 1925, the GAA's Central Council took the decision to name a stand in Croke Park after Michael Hogan. The 21st November 2020 marks one hundred years since the events of Bloody Sunday in Croke Park. Tipperary Team, Bloody Sunday 1920

Tipperary Team, Bloody Sunday 1920 Michael Hogan

Michael Hogan -

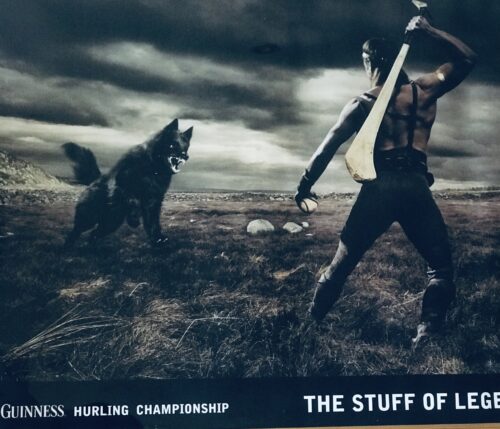

Superb Guinness advert publicising their sponsorship of the All Ireland Senior Hurling Championship-unframed print. 44cm x 60cm Guinness were long time sponsors of the All Ireland Senior Hurling Championship.Hurling is an ancient sport ,played for over 2000 years by such mythical Irish legends such as Setanta, who is depicted here in this distinctive Guinness advert fighting off a fierce wolf, armed with just a Hurl and a sliotar! Following on the company’s imaginative marketing and advertising campaigns — with such slogans as ‘Not Men But Giants,’ ‘Nobody Said It Was Going To Be Easy’ and ‘The Stuff of Legend’ — other imaginative adverts brought the message that hurling is part of the Irish DNA. Other campaigns, entitled ‘It’s Alive Inside’ focused on how hurling is an integral part of Irish life and how the love of hurling is alive inside every hurling player and fan.

Superb Guinness advert publicising their sponsorship of the All Ireland Senior Hurling Championship-unframed print. 44cm x 60cm Guinness were long time sponsors of the All Ireland Senior Hurling Championship.Hurling is an ancient sport ,played for over 2000 years by such mythical Irish legends such as Setanta, who is depicted here in this distinctive Guinness advert fighting off a fierce wolf, armed with just a Hurl and a sliotar! Following on the company’s imaginative marketing and advertising campaigns — with such slogans as ‘Not Men But Giants,’ ‘Nobody Said It Was Going To Be Easy’ and ‘The Stuff of Legend’ — other imaginative adverts brought the message that hurling is part of the Irish DNA. Other campaigns, entitled ‘It’s Alive Inside’ focused on how hurling is an integral part of Irish life and how the love of hurling is alive inside every hurling player and fan.