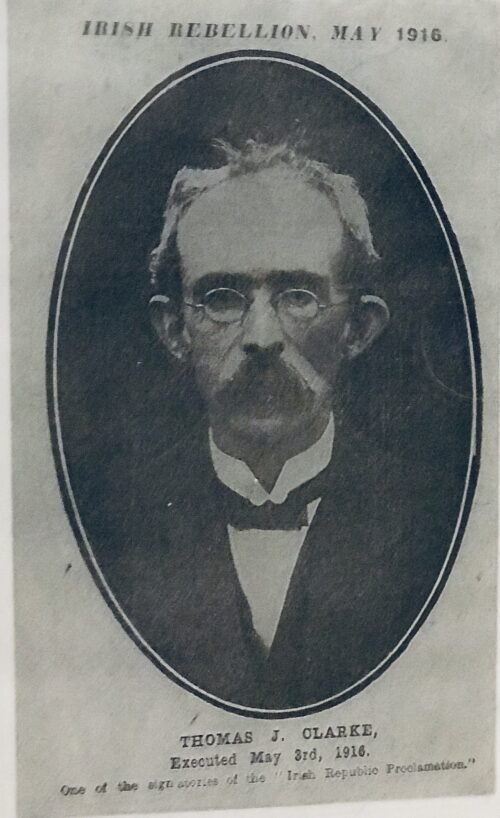

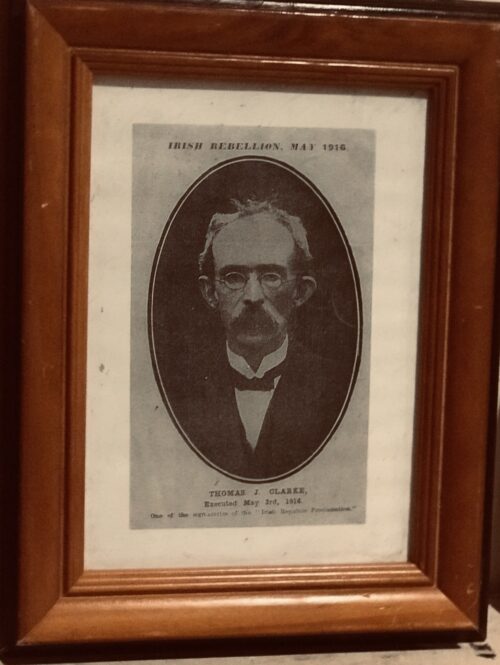

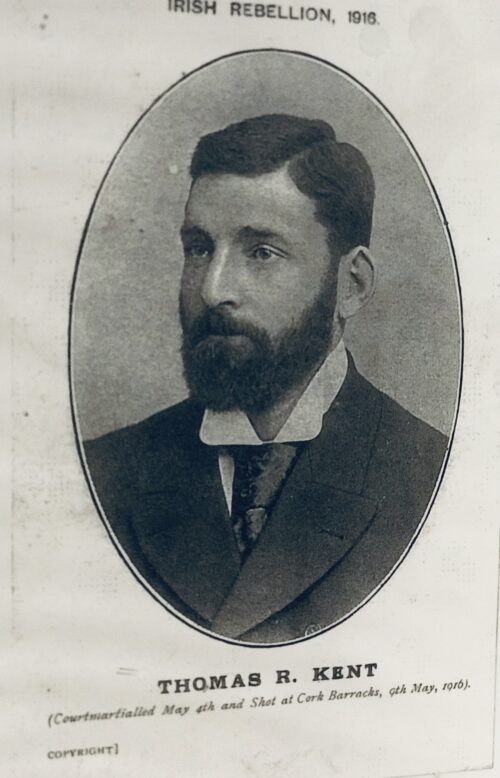

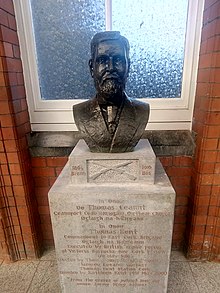

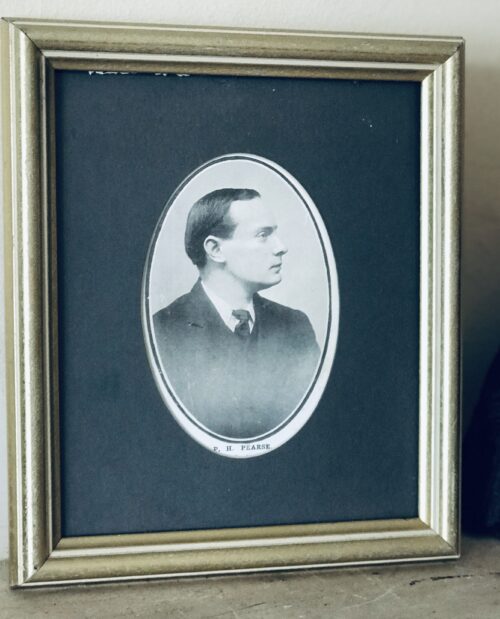

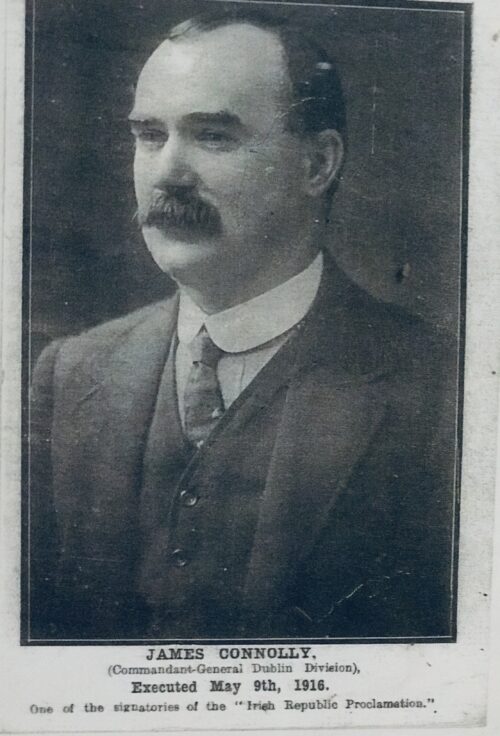

Beautiful and poignant collection of four of the 1916 Easter Rising Rebel Leaders who were executed by the British Crown Forces at Kilmainham Jail a few weeks later.Featured here are Padraig Pearse,Thomas Clarke,James Connolly,Thomas Kent.

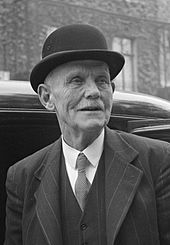

James Connolly (5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an

Irish republican and

socialist leader.

Connolly was born in the

Cowgate area of

Edinburgh, Scotland, to Irish parents. He left school for working life at the age of 11. He also took a role in

Scottish and

American politics. He was a member of the

Industrial Workers of the World and founder of the

Irish Socialist Republican Party. With

James Larkin, he was centrally involved in the

Dublin lock-out of 1913, as a result of which the two men formed the

Irish Citizen Army (ICA) that year. He opposed

British rule in Ireland, and was one of the leaders of the

Easter Rising of 1916. He was executed by firing squad following the Rising.

Early life

Connolly was born in an Edinburgh slum in 1868, the third son of Irish parents John Connolly and Mary McGinn.

His parents had moved to Scotland from

County Monaghan, Ireland, and settled in the Cowgate, a

ghetto where thousands of Irish people lived.

He spoke with a Scottish accent throughout his life.

He was born in

St Patrick's Roman Catholic parish, in the Cowgate district of Edinburgh known as "Little Ireland".

His father and grandfathers were labourers.

He had an education up to the age of about ten in the local Catholic primary school.

He left and worked in labouring jobs. Owing to the economic difficulties he was having,

like his eldest brother John, he joined the

British Army.

He enlisted at age 14,

falsifying his age and giving his name as Reid, as his brother John had done.

He served in Ireland with the 2nd Battalion of the

Royal Scots Regiment for nearly seven years, during a turbulent period in rural areas known as the

Land War.

He would later become involved in the land issue.

He developed a deep hatred for the British Army that lasted his entire life.

When he heard that his regiment was being transferred to India, he deserted.

Connolly had another reason for not wanting to go to India; a young woman by the name of

Lillie Reynolds.

Lillie moved to Scotland with James after he left the army and they married in April 1890.

They settled in Edinburgh. There, Connolly began to get involved in the

Scottish Socialist Federation,

[17] but with a young family to support, he needed a way to provide for them.

He briefly established a

cobbler's shop in 1895, but this failed after a few months

as his shoe-mending skills were insufficient.

He was strongly active with the socialist movement at the time, and prioritized this over his cobbling.

Socialist involvement

After Ireland is free, says the patriot who won't touch Socialism, we will protect all classes, and if you won't pay your rent you will be evicted same as now. But the evicting party, under command of the sheriff, will wear green uniforms and the

Harp without the Crown, and the warrant turning you out on the roadside will be stamped with the arms of the Irish Republic.

In the 1880s, Connolly became influenced by

Friedrich Engels and

Karl Marx and would later advocate a type of socialism that was based in

Marxist theory.

[21] Connolly described himself as a socialist, while acknowledging the influence of Marx.

He became secretary of the Scottish Socialist Federation. At the time his brother John was secretary; after John spoke at a rally in favour of the

eight-hour day, however, he was fired from his job with the Edinburgh Corporation, so while he looked for work, James took over as secretary. During this time, Connolly became involved with the

Independent Labour Party which

Keir Hardie had formed in 1893. At some time during this period, he took up the study of, and advocated the use of, the neutral international language,

Esperanto.

His interest in Esperanto is implicit in his 1898 article "The Language Movement", which primarily attempts to promote socialism to the nationalist revolutionaries involved in the Gaelic Revival.

By 1892 he was involved in the

Scottish Socialist Federation, acting as its secretary from 1895. Two months after the birth of his third daughter, word came to Connolly that the Dublin Socialist Club was looking for a full-time secretary, a job that offered a salary of a pound a week.

Connolly and his family moved to Dublin,

where he took up the position. At his instigation, the club quickly evolved into the

Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP).

The ISRP is regarded by many Irish historians as a party of pivotal importance in the early history of Irish socialism and republicanism. While active as a socialist in Great Britain, Connolly was the founding editor of

The Socialist newspaper and was among the founders of the

Socialist Labour Partywhich split from the

Social Democratic Federation in 1903. Connolly joined Maud Gonne and Arthur Griffith in the Dublin protests against the

Boer War.

A combination of frustration with the progress of the ISRP and economic necessity caused him to emigrate to the United States in September 1903, with no plans as to what he would do there.

While in America he was a member of the

Socialist Labor Party of America (1906), the

Socialist Party of America (1909) and the

Industrial Workers of the World, and founded the

Irish Socialist Federation in New York, 1907. He famously had a chapter of his 1910 book

Labour in Irish History entitled "A chapter of horrors:

Daniel O’Connell and the working class." critical of the achiever of

Catholic Emancipation 60 years earlier.

On Connolly's return to Ireland in 1910 he was right-hand man to

James Larkin in the

Irish Transport and General Workers Union. He stood twice for the Wood Quay ward of

Dublin Corporation but was unsuccessful. His name, and those of his family, appears in the 1911 Census of Ireland - his occupation is listed as "National Organiser Socialist Party".

In 1913, in response to the

Lockout, he, along with an ex-British officer,

Jack White, founded the

Irish Citizen Army (ICA), an armed and well-trained body of labour men whose aim was to defend workers and strikers, particularly from the frequent brutality of the

Dublin Metropolitan Police. Though they only numbered about 250 at most, their goal soon became the establishment of an independent and socialist Irish nation. He also founded the

Irish Labour Party as the political wing of the

Irish Trades Union Congress in 1912 and was a member of its National Executive. Around this time he met

Winifred Carney in

Belfast, who became his secretary and would later accompany him during the

Easter Rising. Like

Vladimir Lenin, Connolly opposed the

First World War explicitly from a socialist perspective. Rejecting the

Redmondite position, he declared "I know of no foreign enemy of this country except the British Government."

Easter Rising

Connolly and the ICA made plans for an armed uprising during the war, independently of the

Irish Volunteers. In early 1916, believing the Volunteers were dithering, he attempted to goad them into action by threatening to send the ICA against the

British Empire alone, if necessary. This alarmed the members of the

Irish Republican Brotherhood, who had already infiltrated the Volunteers and had plans for an insurrection that very year. In order to talk Connolly out of any such rash action, the IRB leaders, including

Tom Clarke and

Patrick Pearse, met with Connolly to see if an agreement could be reached. During the meeting, the IRB and the ICA agreed to act together at

Easter of that year.

During the

Easter Rising, beginning on 24 April 1916, Connolly was Commandant of the Dublin Brigade. As the Dublin Brigade had the most substantial role in the rising, he was

de factocommander-in-chief. Connolly's leadership in the Easter rising was considered formidable.

Michael Collins said of Connolly that he "would have followed him through hell."

Following the surrender, he said to other prisoners: "Don't worry. Those of us that signed the proclamation will be shot. But the rest of you will be set free."

Death

Connolly was not actually held in gaol, but in a room (now called the "Connolly Room") at the State Apartments in

Dublin Castle, which had been converted to a first-aid station for troops recovering from the

war.

Connolly was sentenced to death by firing squad for his part in the rising. On 12 May 1916 he was taken by military ambulance to

Royal Hospital Kilmainham, across the road from

Kilmainham Gaol, and from there taken to the gaol, where he was to be executed. While Connolly was still in hospital in Dublin Castle, during a visit from his wife and daughter, he said: "The Socialists will not understand why I am here; they forget I am an Irishman."

Connolly had been so badly injured from the fighting (a doctor had already said he had no more than a day or two to live, but the execution order was still given) that he was unable to stand before the firing squad; he was carried to a prison courtyard on a stretcher. His absolution and last rites were administered by a

Capuchin, Father Aloysius Travers. Asked to pray for the soldiers about to shoot him, he said: "I will say a prayer for all men who do their duty according to their lights."

Instead of being marched to the same spot where the others had been executed, at the far end of the execution yard, he was tied to a chair and then shot.

His body (along with those of the other leaders) was put in a mass grave without a coffin. The executions of the rebel leaders deeply angered the majority of the Irish population, most of whom had shown no support during the rebellion. It was Connolly's execution that caused the most controversy.

Historians have pointed to the manner of execution of Connolly and similar rebels, along with their actions, as being factors that caused public awareness of their desires and goals and gathered support for the movements that they had died fighting for.

The executions were not well received, even throughout Britain, and drew unwanted attention from the United States, which the British Government was seeking to bring into the war in Europe.

H. H. Asquith, the Prime Minister, ordered that no more executions were to take place; an exception being that of

Roger Casement, who was charged with

high treasonand had not yet been tried.

Family

James Connolly and his wife Lillie had seven children.

Nora became an influential writer and campaigner within the Irish-republican movement as an adult.

Roddy continued his father's politics. In later years, both became members of the

Oireachtas (Irish parliament). Moira became a doctor and married

Richard Beech.

One of Connolly's daughters Mona died in 1904 aged 13, when she burned herself while she did the washing for an aunt.

Three months after James Connolly's execution his wife was received into the Catholic Church, at Church St. on 15 August.

Legacy

Statue of James Connolly in Dublin

Connolly's legacy in Ireland is mainly due to his contribution to the

republican cause; his legacy as a socialist has been claimed by a variety of left-wing and left-republican groups, and he is also associated with the Labour Party which he founded. Connolly was among the few European members of the

Second International who opposed, outright,

World War I. This put him at odds with most of the socialist leaders of Europe.

He was influenced by and heavily involved with the radical

Industrial Workers of the World labour union, and envisaged socialism as Industrial Union control of production. Also he envisioned the IWW forming their own political party that would bring together the feuding socialist groups such as the

Socialist Labor Party of America and the

Socialist Party of America.

Likewise, he envisaged independent Ireland as a socialist republic. His connection and views on Revolutionary Unionism and Syndicalism have raised debate on if his image for a workers republic would be one of State or Grassroots socialism.

For a time he was involved with

De Leonism and the

Second International until he later broke with both.

In Scotland, Connolly's thinking influenced socialists such as

John Maclean, who would, like him, combine his leftist thinking with nationalist ideas when he formed the

Scottish Workers Republican Party.

Statue of James Connolly in Belfast

The

Connolly Association, a British organisation campaigning for Irish unity and independence, is named after Connolly.

In 1928, Follonsby miners' lodge in the Durham coalfield unfurled a newly designed banner that included a portrait of Connolly on it. The banner was burned in 1938, replaced but then painted over in 1940. A reproduction of the 1938 Connolly banner was commissioned in 2011 by the Follonsby Miners’ Lodge Banner Association and it is regularly paraded at various events in County Durham ('Old King Coal' at Beamish Open Air museum, 'The Seven men of Jarrow' commemoration every June, the

Durham Miners' Gala every second Saturday in July, the Tommy Hepburn annual memorial every October), in the wider UK and Ireland.

There is a statue of James Connolly in Dublin, outside

Liberty Hall, the offices of the

SIPTU trade union. Another statue of Connolly stands in Union Park, Chicago near the offices of the

UE union. There is a bust of Connolly in

Troy, New York, in the park behind the statue of Uncle Sam.

In March 2016 a statue of Connolly was unveiled by

Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure minister

Carál Ní Chuilín, and Connolly's great grandson, James Connolly Heron, on

Falls Road in Belfast.

In a 1972 interview on

The Dick Cavett Show,

John Lennon stated that James Connolly was an inspiration for his song, "

Woman Is the Nigger of the World". Lennon quoted Connolly's 'the female is the slave of the slave' in explaining the feminist inspiration for the song.

Connolly Station, one of the two main railway stations in Dublin, and

Connolly Hospital, Blanchardstown, are named in his honour.

In a 2002,

BBC television production,

100 Greatest Britons where the British public were asked to register their vote, Connolly was voted in 64th place.

In 1968, Irish group

The Wolfe Tones released a single named "James Connolly", which reached number 15 in the Irish charts.

The band

Black 47 wrote and performed a song about Connolly that appears on their album

Fire of Freedom. Irish singer-songwriter Niall Connolly has a song

"May 12th, 1916 - A Song for James Connolly" on his album

Dream Your Way Out of This One(2017).