-

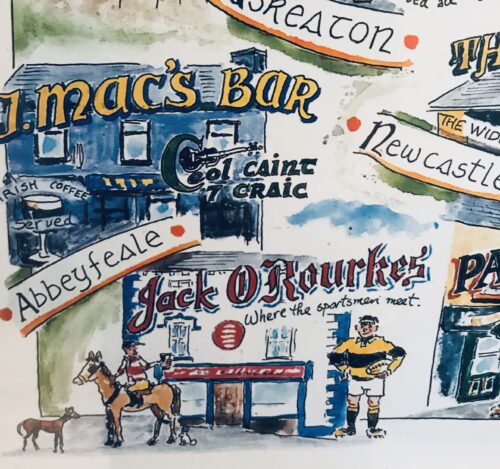

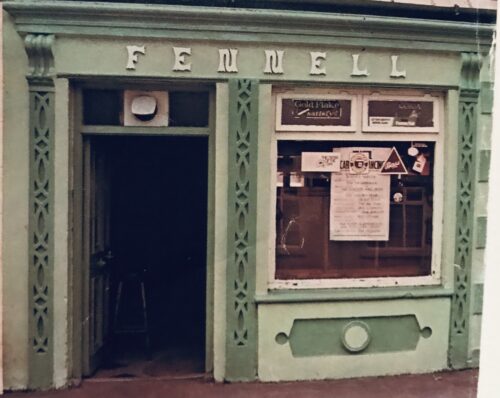

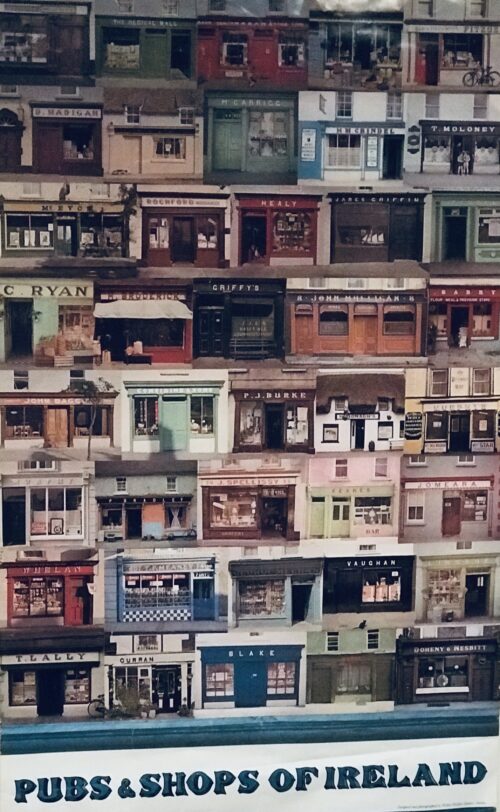

88cm x 52cm In olden times the traditional Irish country pub also often functioned as a grocery,sweetshop,veterinary chemist,hardware store and haberdashery where patrons could partake in a soothing drink after shopping alongside displays of chocolate bars, tins of canned fruit, reels of hay bailer twine, and tubs of sheep dip.Sadly grocery bars are now few and far between but the ones that survive are a throwback to an old and innocent way of life.Dingle in Co Kerry is home to many of the best surviving examples of the pub-grocer.In the famous Currans on Main Street ,the pub always doubled as a general merchant.They sold everything and supplied the townspeople and farmers who would pile into the town on Fairday.The old ledgers still in existence are stuffed with billheads from all types of suppliers- everything was sold -ropes.twines,seeds,ales,buckets,hams,jams,fishing nets,flowers,ladies rubber heels and tights, cloth caps, shirts,boots- the list is endless.

88cm x 52cm In olden times the traditional Irish country pub also often functioned as a grocery,sweetshop,veterinary chemist,hardware store and haberdashery where patrons could partake in a soothing drink after shopping alongside displays of chocolate bars, tins of canned fruit, reels of hay bailer twine, and tubs of sheep dip.Sadly grocery bars are now few and far between but the ones that survive are a throwback to an old and innocent way of life.Dingle in Co Kerry is home to many of the best surviving examples of the pub-grocer.In the famous Currans on Main Street ,the pub always doubled as a general merchant.They sold everything and supplied the townspeople and farmers who would pile into the town on Fairday.The old ledgers still in existence are stuffed with billheads from all types of suppliers- everything was sold -ropes.twines,seeds,ales,buckets,hams,jams,fishing nets,flowers,ladies rubber heels and tights, cloth caps, shirts,boots- the list is endless. -

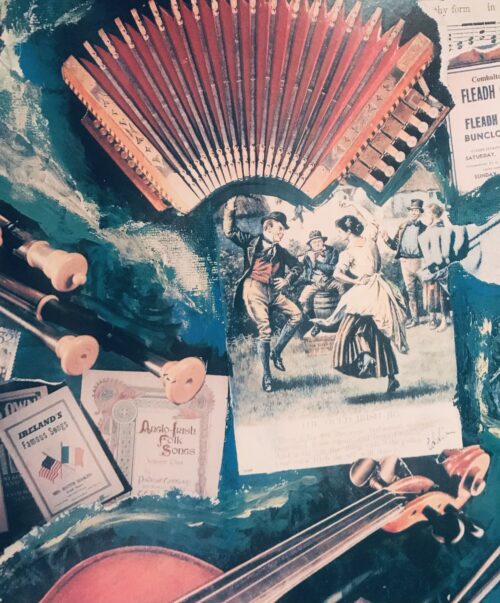

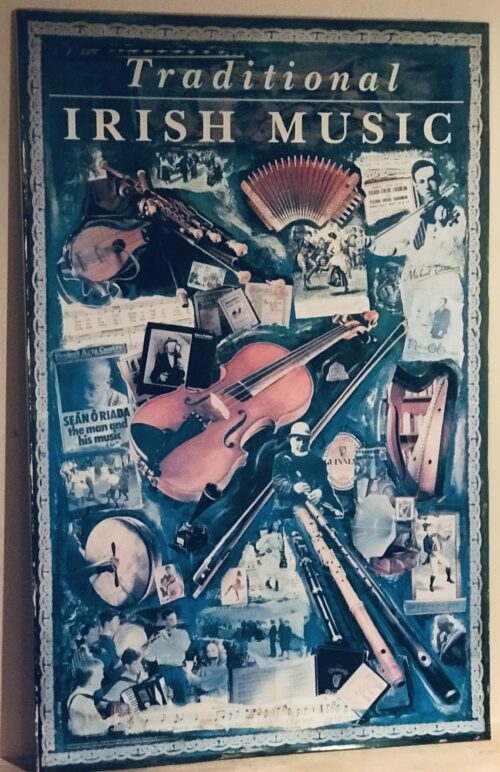

Large,colourful,beautifully illustrated and wonderfully eclectic poster depicting Irish Traditional Music instruments,scenes and imagery which have been such an integral part of Irish culture and heritage, featuring such luminaries as Sean O'Riada,The Chieftains etc. 85cm x 55cm Irish Traditional music (also known as Irish trad, Irish folk music, and other variants) is a genre of folk music that developed in Ireland. In A History of Irish Music (1905), W. H. Grattan Flood wrote that, in Gaelic Ireland, there were at least ten instruments in general use. These were the cruit (a small harp) and clairseach (a bigger harp with typically 30 strings), the timpan (a small string instrument played with a bow or plectrum), the feadan (a fife), the buinne (an oboe or flute), the guthbuinne (a bassoon-type horn), the bennbuabhal and corn (hornpipes), the cuislenna (bagpipes – see Great Irish warpipes), the stoc and sturgan (clarions or trumpets), and the cnamha (bones). There is also evidence of the fiddle being used in the 8th century. There are several collections of Irish folk music from the 18th century, but it was not until the 19th century that ballad printers became established in Dublin. Important collectors include Colm Ó Lochlainn, George Petrie, Edward Bunting, Francis O'Neill, James Goodman and many others. Though solo performance is preferred in the folk tradition, bands or at least small ensembles have probably been a part of Irish music since at least the mid-19th century, although this is a point of much contention among ethnomusicologists. Irish traditional music has endured more strongly against the forces of cinema, radio and the mass media than the indigenous folk music of most European countries. This was possibly because the country was not a geographical battleground in either of the two World Wars. Another potential factor was that the economy was largely agricultural, where oral tradition usually thrives. From the end of the Second World War until the late fifties folk music was held in low regard. Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (an Irish traditional music association) and the popularity of the Fleadh Cheoil(music festival) helped lead the revival of the music. The English Folk music scene also encouraged and gave self-confidence to many Irish musicians. Following the success of The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem in the US in 1959, Irish folk music became fashionable again. The lush sentimental style of singers such as Delia Murphy was replaced by guitar-driven male groups such as The Dubliners. Irish showbands presented a mixture of pop music and folk dance tunes, though these died out during the seventies. The international success of The Chieftains and subsequent musicians and groups has made Irish folk music a global brand. Historically much old-time music of the USA grew out of the music of Ireland, England and Scotland, as a result of cultural diffusion. By the 1970s Irish traditional music was again influencing music in the US and further afield in Australia and Europe. It has occasionally been fused with rock and roll, punk rock and other genres. Irish dance music is isometric and is built around patterns of bar-long melodic phrases akin to call and response. A common pattern is A Phrase, B Phrase, A Phrase, Partial Resolution, A Phrase, B Phrase, A Phrase, Final Resolution, though this is not universal; mazurkas, for example, tend to feature a C Phrase instead of a repeated A Phrase before the Partial and Final Resolutions, for example. Many tunes have pickup notes which lead in to the beginning of the A or B parts. Mazurkas and hornpipes have a swing feel, while other tunes have straight feels. Tunes are typically binary in form, divided into two (or sometimes more) parts, each with four to eight bars. The parts are referred to as the A-part, B-part, and so on. Each part is played twice, and the entire tune is played three times; AABB, AABB, AABB. Many tunes have similar ending phrases for both A and B parts; it is common for hornpipes to have the second half of each part be identical. Additionally, hornpipes often have three quavers or quarternotes at the end of each part, followed by pickup notes to lead back to the beginning of the A part of onto the B part. Many airshave an AABA form.While airs are usually played singly, dance tunes are usually played in medleys of 2-4 tunes called sets. Irish music generally is modal, using ionian, aeolian, dorian, and mixolydian modes, as well as hexatonic and pentatonic versions of those scales. Some tunes do feature accidentals.Singers and instrumentalists often embellish melodies through ornamentation, using grace notes, rolls, cuts, crans, or slides. While uilleann pipes may use their drones and chanters to provide harmonic backup, and fiddlers often use double stops in their playing, due to the importance placed on the melody in Irish music, harmony is typically kept simple or absent.Usually, instruments are played in strict unison, always following the leading player. True counterpoint is mostly unknown to traditional music, although a form of improvised "countermelody" is often used in the accompaniments of bouzouki and guitar players. In contrast to many kinds of western folk music, there are no set chord progressions to tunes; many accompanyists use power chords to let the melody define the tonality or use partial chords in combination with ringing drone strings to emphasize the tonal center. Many guitarists use DADGAD tuning because it offers flexibility in using these approaches, as does the GDAD tuning for bouzouki. Like all traditional music, Irish folk music has changed slowly. Most folk songs are less than 200 years old. One measure of its age is the language used. Modern Irish songs are written in English and Irish. Most of the oldest songs and tunes are rural in origin and come from the older Irish language tradition. Modern songs and tunes often come from cities and towns, Irish songs went from the Irish language to the English language. Unaccompanied vocals are called sean nós ("in the old style") and are considered the ultimate expression of traditional singing. This is usually performed solo (very occasionally as a duet). Sean-nós singing is highly ornamented and the voice is placed towards the top of the range. A true sean-nós singer will vary the melody of every verse, but not to the point of interfering with the words, which are considered to have as much importance as the melody. Sean-nós can include non-lexical vocables, called lilting, also referred to by the sounds, such as "diddly die-dely". Non-sean-nós traditional singing, even when accompaniment is used, uses patterns of ornamentation and melodic freedom derived from sean-nós singing, and, generally, a similar voice placement. Caoineadh is Irish for a lament, a song which is typified by lyrics which stress sorrow and pain. Traditionally, the Caoineadh song contained lyrics in which the singer lamented for Ireland after having been forced to emigrate due to political or financial reasons. The song may also lament the loss of a loved one (particularly a fair woman). Many Caoineadh songs have their roots/basis in The Troubles of Northern Ireland with particular reference to the presence of the British military during this period. Examples of Caoineadh songs include: Far Away in Australia, The Town I Loved So Well and Four Green Fields. Caoineadh singers were originally paid to lament for the departed at funerals, according to a number of Irish sources. Irish traditional music and dance has seen a variety of settings, from house parties, country dances, ceili dances, stage performances and competitions, weddings, saint's days or other observances. The most common setting for Irish dance music is the seisiun, which very often features no dancing at all. The concept of "style" is of large importance to Irish traditional musicians. At the start of the last century (1900), distinct variation in regional styles of performance existed. With the release of American recordings of Irish traditional musicians (e.g. Michael Coleman 1927) and increased communications and travel opportunities, regional styles have become more standardised. Regional playing styles remain nonetheless, as evidenced by the very different playing styles of musicians from Donegal (e.g. Tommy Peoples), Clare (e.g. brothers John & James Kelly) and Sliabh Luachra (e.g. Jacky Daly). Donegal fiddle playing is characterised by fast, energetic bowing, with the bow generating the majority of the ornamentation; Clare fiddle playing is characterised by slower bowing, with the fingering generating most of the ornamentation. While bowed triplets (three individual notes with the bow reversed between each) are more common in Donegal, fingered triplets and fingered rolls (five individual notes fingered with a single bow stroke) are very common in Clare. Stage performers from the 1970s and 1980s (groups such as The Bothy Band, or soloists such as Kevin Burke) have used the repertoire of traditional music to create their own groups of tunes, without regard to the conventional 'sets' or the constraint of playing for dancers. Burke's playing is an example of an individual, unique, distinctive style, a hybrid of his classical training, the traditional Sligo fiddle style and various other influences. The most common instruments used in Irish traditional dance music, whose history goes back several hundred years, are the fiddle, tin whistle, flute and Uilleann pipes. Instruments such as button accordion and concertina made their appearances in Irish traditional music late in the 19th century. The 4-string tenor banjo, first used by Irish musicians in the US in the 1920s, is now fully accepted. The guitar was used as far back as the 1930s first appearing on some of the recordings of Michael Coleman and his contemporaries. The bouzouki only entered the traditional Irish music world in the late 1960s. The word bodhrán, indicating a drum, is first mentioned in a translated English document in the 17th century. The saxophone featured in recordings from the early 20th century most notably in Paddy Killoran's Pride of Erin Orchestra. Céilidh bands of the 1940s often included a drum set and stand-up bass as well as saxophones. Traditional harp-playing died out in the late 18th century, and was revived by the McPeake Family of Belfast, Derek Bell, Mary O'Hara and others in the mid-20th century. Although often encountered, it plays a fringe role in Irish Traditional dance music. The piano is commonly used for accompaniment. In the early 20th century piano accompaniment was prevalent on the 78rpm records featuring Michael Coleman, James Morrison, John McKenna, PJ Conlon and many more. On many of these recordings the piano accompaniment was woeful because the backers were unfamiliar with Irish music. However, Morrison avoided using the studio piano players and hand-picked his own. The vamping style used by these piano backers has largely remained. There has been a few recent innovators such as Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin, Brian McGrath, Liam Bradley, Josephine Keegan, Ryan Molloy and others. One of the most important instruments in the traditional repertoire, the fiddle (or violin – there is no physical difference) is played differently in widely varying regional styles. It uses the standard GDAE tuning. The best-known regional fiddling traditions are from Donegal, Sligo, Sliabh Luachra and Clare. The fiddling tradition of Sligo is perhaps most recognisable to outsiders, due to the popularity of American-based performers like Lad O'Beirne, Michael Coleman, John McGrath, James Morrison and Paddy Killoran. These fiddlers did much to popularise Irish music in the States in the 1920s and 1930s. Other Sligo fiddlers included Martin Wynne and Fred Finn. Notable fiddlers from Clare include Mary Custy, Yvonne Casey, Paddy Canny, Bobby Casey, John Kelly, Patrick Kelly, Peadar O'Loughlin, Pat O'Connor, Martin Hayes and P. Joe Hayes. Donegal has produced James Byrne, Vincent Campbell, John Doherty, Tommy Peoples, and Con Cassidy. Sliabh Luachra, a small area between Kerry and Cork, is known for Julia Clifford, her brother Denis Murphy, Sean McGuire, Paddy Cronin and Padraig O'Keeffe. Contemporary fiddlers from Sliabh Luachra include Matt Cranitch, Gerry Harrington and Connie O'Connell, while Dubliner Séamus Creagh, actually from Westmeath, is imbued in the local style. Modern performers include Kevin Burke, Máire Breatnach, Matt Cranitch, Paddy Cronin, Frankie Gavin, Paddy Glackin, Cathal Hayden, Martin Hayes, Peter Horan, Sean Keane, James Kelly, Mairéad Ní Mhaonaigh, Brendan Mulvihill, Máiréad Nesbitt, Gerry O'Connor, Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh, and Paul O'Shaughnessy. There have been many notable fiddlers from United States in recent years such as Winifred Horan, Brian Conway, Liz Carroll, and Eileen Ivers. The flute has been an integral part of Irish traditional music since roughly the middle of the 19th century, when art musicians largely abandoned the wooden simple-system flute (having a conical bore, and fewer keys) for the metal Boehm system flutes of present-day classical music. Although the choice of the Albert-system, wooden flute over the metal was initially driven by the fact that, being "outdated" castoffs, the old flutes were available cheaply second-hand, the wooden instrument has a distinct sound and continues to be commonly preferred by traditional musicians to this day. A number of excellent players—Joanie Madden being perhaps the best known—use the Western concert flute, but many others find that the simple system flute best suits traditional fluting. Original flutes from the pre-Boehm era continue in use, but since the 1960s a number of craftsmen have revived the art of wooden flute making. Some flutes are even made of PVC; these are especially popular with new learners and as travelling instruments, being both less expensive than wooden instruments and far more resistant to changes in humidity. The tin whistle or metal whistle, which with its nearly identical fingering might be called a cousin of the simple-system flute, is also popular. It was mass-produced in 19th century Manchester England, as an inexpensive instrument. Clarke whistles almost identical to the first ones made by that company are still available, although the original version, pitched in C, has mostly been replaced for traditional music by that pitched in D, the "basic key" of traditional music. The other common design consists of a barrel made of seamless tubing fitted into a plastic or wooden mouthpiece. Skilled craftsmen make fine custom whistles from a range of materials including not only aluminium, brass, and steel tubing but synthetic materials and tropical hardwoods; despite this, more than a few longtime professionals stick with ordinary factory made whistles. Irish schoolchildren are generally taught the rudiments of playing on the tin whistle, just as school children in many other countries are taught the soprano recorder. At one time the whistle was thought of by many traditional musicians as merely a sort of "beginner's flute", but that attitude has disappeared in the face of talented whistlers such as Mary Bergin, whose classic early seventies recording Feadóga Stáin (with bouzouki accompaniment by Alec Finn) is often credited with revolutionising the whistle's place in the tradition. The low whistle, a derivative of the common tin whistle, is also popular, although some musicians find it less agile for session playing than the flute or the ordinary D whistle. Notable present-day flute-players (sometimes called 'flautists' or 'fluters') include Matt Molloy, Kevin Crawford, Peter Horan, Michael McGoldrick, Desi Wilkinson, Conal O'Grada, James Carty, Emer Mayock, Joanie Madden, Michael Tubridy and Catherine McEvoy, while whistlers include Paddy Moloney, Carmel Gunning, Paddy Keenan, Seán Ryan, Andrea Corr, Mary Bergin, Packie Byrne and Cormac Breatnach.Uilleann pipes (pronounced ill-in or ill-yun depending upon local dialect) are a complex instrument. Tradition holds that seven years learning, seven years practising and seven years playing is required before a piper could be said to have mastered his instrument. The uilleann pipes developed around the beginning of the 18th century, the history of which is depicted in carvings and pictures from contemporary sources in both Britain and Ireland as pastoraland union pipes. Its modern form had arrived by the end of the 18th century, and was played by gentlemen pipers such as the mid-18th century piper Jackson from Limerick and the Tandragee pipemaker William Kennedy, the Anglican clergyman Canon James Goodman (1828–1896) and his friend John Hingston from Skibbereen. These were followed in the 20th century by the likes of Séamus Ennis, Leo Rowsome and Willie Clancy, playing refined and ornate pieces, as well as showy, ornamented forms played by travelling pipers like John Cash and Johnny Doran.The uilleann piping tradition had nearly died before being re-popularized by the likes of Paddy Moloney (of the Chieftains), and the formation of Na Píobairí Uilleann, an organisation open to pipers that included such players as Rowsome and Ennis, as well as researcher and collector Breandán Breathnach. Liam O'Flynn is one of the most popular of modern performers along with Paddy Keenan, John McSherry, Davy Spillane, Jerry O'Sullivan, Mick O'Brien and many more. Many Pavee (Traveller) families, such as the Fureys and Dorans and Keenans, are famous for the pipers among them. Famous was also the McPeake Family, who toured Europe. Uilleann pipes are among the most complex forms of bagpipes; they possess a chanter with a double reed and a two-octave range, three single-reed drones, and, in the complete version known as a full set, a trio of (regulators) all with double reeds and keys worked by the piper's forearm, capable of providing harmonic support for the melody. (Virtually all uilleann pipers begin playing with a half set, lacking the regulators and consisting of only bellows, bag, chanter, and drones. Some choose never to play the full set, and many make little use of the regulators.) The bag is filled with air by a bellows held between the piper's elbow and side, rather than by the performer's lungs as in the highland pipes and almost all other forms of bagpipe, aside from the Scottish smallpipes, Pastoral pipes (which also plays with regulators), the Northumbrian pipes of northern England, and the Border pipes found in both parts of the Anglo-Scottish Border country. The uilleann pipes play a prominent part in a form of instrumental music called Fonn Mall, closely related to unaccompanied singing an sean nós ("in the old style"). Willie Clancy, Leo Rowsome, and Garret Barry were among the many pipers famous in their day; Paddy Keenan, Davy Spillane and Robbie Hannan play these traditional airs today, among many others. The harp is among the chief symbols of Ireland. The Celtic harp, seen on Irish coinage and used in Guinness advertising, was played as long ago as the 10th century. In ancient times, the harpers were greatly respected and, along with poets and scribes, assigned a high place amongst the most significant retainers of the old Gaelic order of lords and chieftains. Perhaps the best known representative of this tradition of harping today is Turlough Ó Carolan, a blind 18th century harper who is often considered the unofficial national composer of Ireland. Thomas Connellan, a slightly earlier Sligo harper, composed such well known airs as "The Dawning of the Day"/"Raglan Road" and "Carolan's Dream". The native Irish harping tradition was an aristocratic art music with its own canon and rules for arrangement and compositional structure, only tangentially associated with the folkloric music of the common people, the ancestor of present-day Irish traditional music. Some of the late exponents of the harping tradition, such as O'Carolan, were influenced by the Italian Baroque art music of such composers as Vivaldi, which could be heard in the theatres and concert halls of Dublin. The harping tradition did not long outlast the native Gaelic aristocracy which supported it. By the early 19th century, the Irish harp and its music were for all intents and purposes dead. Tunes from the harping tradition survived only as unharmonised melodies which had been picked up by the folkloric tradition, or were preserved as notated in collections such as Edward Bunting's, (he attended the Belfast Harp Festival in 1792) in which the tunes were most often modified to make them fit for the drawing room pianofortes of the Anglicised middle and upper classes. The first generations of 20th century revivalists, mostly playing the gut-strung (frequently replaced with nylon after the Second World War) neo-Celtic harp with the pads of their fingers rather than the old brass-strung harp plucked with long fingernails, tended to take the dance tunes and song airs of Irish traditional music, along with such old harp tunes as they could find, and applied to them techniques derived from the orchestral (pedal) harp and an approach to rhythm, arrangement, and tempo that often had more in common with mainstream classical music than with either the old harping tradition or the living tradition of Irish music. A separate Belfast tradition of harp-accompanied folk-singing was preserved by the McPeake Family. Over the past thirty years a revival of the early Irish harp has been growing, with replicas of the medieval instruments being played, using strings of brass, silver, and even gold. This revival grew through the work of a number of musicians including Arnold Dolmetsch in 1930s England, Alan Stivell in 1960s Brittany, and most importantly Ann Heymann in the US from the 1970s to the present. Notable players of the modern harp include Derek Bell (of The Chieftains), Laoise Kelly (of The Bumblebees), Gráinne Hambly, Máire Ní Chathasaigh, Mary O'Hara, Antoinette McKenna, Michael Rooney, Áine Minogue, Patrick Ball and Bonnie Shaljean. The best of these have a solid background in genuine Irish traditional music, often having strong competency on another instrument more common in the living tradition, such as the fiddle or concertina, and work very hard at adapting the harp to traditional music, as well as reconstructing what they can of the old harpers' music on the basis of the few manuscript sources which exist. However, the harp continues to occupy a place on the fringe of Irish traditional music.

Large,colourful,beautifully illustrated and wonderfully eclectic poster depicting Irish Traditional Music instruments,scenes and imagery which have been such an integral part of Irish culture and heritage, featuring such luminaries as Sean O'Riada,The Chieftains etc. 85cm x 55cm Irish Traditional music (also known as Irish trad, Irish folk music, and other variants) is a genre of folk music that developed in Ireland. In A History of Irish Music (1905), W. H. Grattan Flood wrote that, in Gaelic Ireland, there were at least ten instruments in general use. These were the cruit (a small harp) and clairseach (a bigger harp with typically 30 strings), the timpan (a small string instrument played with a bow or plectrum), the feadan (a fife), the buinne (an oboe or flute), the guthbuinne (a bassoon-type horn), the bennbuabhal and corn (hornpipes), the cuislenna (bagpipes – see Great Irish warpipes), the stoc and sturgan (clarions or trumpets), and the cnamha (bones). There is also evidence of the fiddle being used in the 8th century. There are several collections of Irish folk music from the 18th century, but it was not until the 19th century that ballad printers became established in Dublin. Important collectors include Colm Ó Lochlainn, George Petrie, Edward Bunting, Francis O'Neill, James Goodman and many others. Though solo performance is preferred in the folk tradition, bands or at least small ensembles have probably been a part of Irish music since at least the mid-19th century, although this is a point of much contention among ethnomusicologists. Irish traditional music has endured more strongly against the forces of cinema, radio and the mass media than the indigenous folk music of most European countries. This was possibly because the country was not a geographical battleground in either of the two World Wars. Another potential factor was that the economy was largely agricultural, where oral tradition usually thrives. From the end of the Second World War until the late fifties folk music was held in low regard. Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (an Irish traditional music association) and the popularity of the Fleadh Cheoil(music festival) helped lead the revival of the music. The English Folk music scene also encouraged and gave self-confidence to many Irish musicians. Following the success of The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem in the US in 1959, Irish folk music became fashionable again. The lush sentimental style of singers such as Delia Murphy was replaced by guitar-driven male groups such as The Dubliners. Irish showbands presented a mixture of pop music and folk dance tunes, though these died out during the seventies. The international success of The Chieftains and subsequent musicians and groups has made Irish folk music a global brand. Historically much old-time music of the USA grew out of the music of Ireland, England and Scotland, as a result of cultural diffusion. By the 1970s Irish traditional music was again influencing music in the US and further afield in Australia and Europe. It has occasionally been fused with rock and roll, punk rock and other genres. Irish dance music is isometric and is built around patterns of bar-long melodic phrases akin to call and response. A common pattern is A Phrase, B Phrase, A Phrase, Partial Resolution, A Phrase, B Phrase, A Phrase, Final Resolution, though this is not universal; mazurkas, for example, tend to feature a C Phrase instead of a repeated A Phrase before the Partial and Final Resolutions, for example. Many tunes have pickup notes which lead in to the beginning of the A or B parts. Mazurkas and hornpipes have a swing feel, while other tunes have straight feels. Tunes are typically binary in form, divided into two (or sometimes more) parts, each with four to eight bars. The parts are referred to as the A-part, B-part, and so on. Each part is played twice, and the entire tune is played three times; AABB, AABB, AABB. Many tunes have similar ending phrases for both A and B parts; it is common for hornpipes to have the second half of each part be identical. Additionally, hornpipes often have three quavers or quarternotes at the end of each part, followed by pickup notes to lead back to the beginning of the A part of onto the B part. Many airshave an AABA form.While airs are usually played singly, dance tunes are usually played in medleys of 2-4 tunes called sets. Irish music generally is modal, using ionian, aeolian, dorian, and mixolydian modes, as well as hexatonic and pentatonic versions of those scales. Some tunes do feature accidentals.Singers and instrumentalists often embellish melodies through ornamentation, using grace notes, rolls, cuts, crans, or slides. While uilleann pipes may use their drones and chanters to provide harmonic backup, and fiddlers often use double stops in their playing, due to the importance placed on the melody in Irish music, harmony is typically kept simple or absent.Usually, instruments are played in strict unison, always following the leading player. True counterpoint is mostly unknown to traditional music, although a form of improvised "countermelody" is often used in the accompaniments of bouzouki and guitar players. In contrast to many kinds of western folk music, there are no set chord progressions to tunes; many accompanyists use power chords to let the melody define the tonality or use partial chords in combination with ringing drone strings to emphasize the tonal center. Many guitarists use DADGAD tuning because it offers flexibility in using these approaches, as does the GDAD tuning for bouzouki. Like all traditional music, Irish folk music has changed slowly. Most folk songs are less than 200 years old. One measure of its age is the language used. Modern Irish songs are written in English and Irish. Most of the oldest songs and tunes are rural in origin and come from the older Irish language tradition. Modern songs and tunes often come from cities and towns, Irish songs went from the Irish language to the English language. Unaccompanied vocals are called sean nós ("in the old style") and are considered the ultimate expression of traditional singing. This is usually performed solo (very occasionally as a duet). Sean-nós singing is highly ornamented and the voice is placed towards the top of the range. A true sean-nós singer will vary the melody of every verse, but not to the point of interfering with the words, which are considered to have as much importance as the melody. Sean-nós can include non-lexical vocables, called lilting, also referred to by the sounds, such as "diddly die-dely". Non-sean-nós traditional singing, even when accompaniment is used, uses patterns of ornamentation and melodic freedom derived from sean-nós singing, and, generally, a similar voice placement. Caoineadh is Irish for a lament, a song which is typified by lyrics which stress sorrow and pain. Traditionally, the Caoineadh song contained lyrics in which the singer lamented for Ireland after having been forced to emigrate due to political or financial reasons. The song may also lament the loss of a loved one (particularly a fair woman). Many Caoineadh songs have their roots/basis in The Troubles of Northern Ireland with particular reference to the presence of the British military during this period. Examples of Caoineadh songs include: Far Away in Australia, The Town I Loved So Well and Four Green Fields. Caoineadh singers were originally paid to lament for the departed at funerals, according to a number of Irish sources. Irish traditional music and dance has seen a variety of settings, from house parties, country dances, ceili dances, stage performances and competitions, weddings, saint's days or other observances. The most common setting for Irish dance music is the seisiun, which very often features no dancing at all. The concept of "style" is of large importance to Irish traditional musicians. At the start of the last century (1900), distinct variation in regional styles of performance existed. With the release of American recordings of Irish traditional musicians (e.g. Michael Coleman 1927) and increased communications and travel opportunities, regional styles have become more standardised. Regional playing styles remain nonetheless, as evidenced by the very different playing styles of musicians from Donegal (e.g. Tommy Peoples), Clare (e.g. brothers John & James Kelly) and Sliabh Luachra (e.g. Jacky Daly). Donegal fiddle playing is characterised by fast, energetic bowing, with the bow generating the majority of the ornamentation; Clare fiddle playing is characterised by slower bowing, with the fingering generating most of the ornamentation. While bowed triplets (three individual notes with the bow reversed between each) are more common in Donegal, fingered triplets and fingered rolls (five individual notes fingered with a single bow stroke) are very common in Clare. Stage performers from the 1970s and 1980s (groups such as The Bothy Band, or soloists such as Kevin Burke) have used the repertoire of traditional music to create their own groups of tunes, without regard to the conventional 'sets' or the constraint of playing for dancers. Burke's playing is an example of an individual, unique, distinctive style, a hybrid of his classical training, the traditional Sligo fiddle style and various other influences. The most common instruments used in Irish traditional dance music, whose history goes back several hundred years, are the fiddle, tin whistle, flute and Uilleann pipes. Instruments such as button accordion and concertina made their appearances in Irish traditional music late in the 19th century. The 4-string tenor banjo, first used by Irish musicians in the US in the 1920s, is now fully accepted. The guitar was used as far back as the 1930s first appearing on some of the recordings of Michael Coleman and his contemporaries. The bouzouki only entered the traditional Irish music world in the late 1960s. The word bodhrán, indicating a drum, is first mentioned in a translated English document in the 17th century. The saxophone featured in recordings from the early 20th century most notably in Paddy Killoran's Pride of Erin Orchestra. Céilidh bands of the 1940s often included a drum set and stand-up bass as well as saxophones. Traditional harp-playing died out in the late 18th century, and was revived by the McPeake Family of Belfast, Derek Bell, Mary O'Hara and others in the mid-20th century. Although often encountered, it plays a fringe role in Irish Traditional dance music. The piano is commonly used for accompaniment. In the early 20th century piano accompaniment was prevalent on the 78rpm records featuring Michael Coleman, James Morrison, John McKenna, PJ Conlon and many more. On many of these recordings the piano accompaniment was woeful because the backers were unfamiliar with Irish music. However, Morrison avoided using the studio piano players and hand-picked his own. The vamping style used by these piano backers has largely remained. There has been a few recent innovators such as Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin, Brian McGrath, Liam Bradley, Josephine Keegan, Ryan Molloy and others. One of the most important instruments in the traditional repertoire, the fiddle (or violin – there is no physical difference) is played differently in widely varying regional styles. It uses the standard GDAE tuning. The best-known regional fiddling traditions are from Donegal, Sligo, Sliabh Luachra and Clare. The fiddling tradition of Sligo is perhaps most recognisable to outsiders, due to the popularity of American-based performers like Lad O'Beirne, Michael Coleman, John McGrath, James Morrison and Paddy Killoran. These fiddlers did much to popularise Irish music in the States in the 1920s and 1930s. Other Sligo fiddlers included Martin Wynne and Fred Finn. Notable fiddlers from Clare include Mary Custy, Yvonne Casey, Paddy Canny, Bobby Casey, John Kelly, Patrick Kelly, Peadar O'Loughlin, Pat O'Connor, Martin Hayes and P. Joe Hayes. Donegal has produced James Byrne, Vincent Campbell, John Doherty, Tommy Peoples, and Con Cassidy. Sliabh Luachra, a small area between Kerry and Cork, is known for Julia Clifford, her brother Denis Murphy, Sean McGuire, Paddy Cronin and Padraig O'Keeffe. Contemporary fiddlers from Sliabh Luachra include Matt Cranitch, Gerry Harrington and Connie O'Connell, while Dubliner Séamus Creagh, actually from Westmeath, is imbued in the local style. Modern performers include Kevin Burke, Máire Breatnach, Matt Cranitch, Paddy Cronin, Frankie Gavin, Paddy Glackin, Cathal Hayden, Martin Hayes, Peter Horan, Sean Keane, James Kelly, Mairéad Ní Mhaonaigh, Brendan Mulvihill, Máiréad Nesbitt, Gerry O'Connor, Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh, and Paul O'Shaughnessy. There have been many notable fiddlers from United States in recent years such as Winifred Horan, Brian Conway, Liz Carroll, and Eileen Ivers. The flute has been an integral part of Irish traditional music since roughly the middle of the 19th century, when art musicians largely abandoned the wooden simple-system flute (having a conical bore, and fewer keys) for the metal Boehm system flutes of present-day classical music. Although the choice of the Albert-system, wooden flute over the metal was initially driven by the fact that, being "outdated" castoffs, the old flutes were available cheaply second-hand, the wooden instrument has a distinct sound and continues to be commonly preferred by traditional musicians to this day. A number of excellent players—Joanie Madden being perhaps the best known—use the Western concert flute, but many others find that the simple system flute best suits traditional fluting. Original flutes from the pre-Boehm era continue in use, but since the 1960s a number of craftsmen have revived the art of wooden flute making. Some flutes are even made of PVC; these are especially popular with new learners and as travelling instruments, being both less expensive than wooden instruments and far more resistant to changes in humidity. The tin whistle or metal whistle, which with its nearly identical fingering might be called a cousin of the simple-system flute, is also popular. It was mass-produced in 19th century Manchester England, as an inexpensive instrument. Clarke whistles almost identical to the first ones made by that company are still available, although the original version, pitched in C, has mostly been replaced for traditional music by that pitched in D, the "basic key" of traditional music. The other common design consists of a barrel made of seamless tubing fitted into a plastic or wooden mouthpiece. Skilled craftsmen make fine custom whistles from a range of materials including not only aluminium, brass, and steel tubing but synthetic materials and tropical hardwoods; despite this, more than a few longtime professionals stick with ordinary factory made whistles. Irish schoolchildren are generally taught the rudiments of playing on the tin whistle, just as school children in many other countries are taught the soprano recorder. At one time the whistle was thought of by many traditional musicians as merely a sort of "beginner's flute", but that attitude has disappeared in the face of talented whistlers such as Mary Bergin, whose classic early seventies recording Feadóga Stáin (with bouzouki accompaniment by Alec Finn) is often credited with revolutionising the whistle's place in the tradition. The low whistle, a derivative of the common tin whistle, is also popular, although some musicians find it less agile for session playing than the flute or the ordinary D whistle. Notable present-day flute-players (sometimes called 'flautists' or 'fluters') include Matt Molloy, Kevin Crawford, Peter Horan, Michael McGoldrick, Desi Wilkinson, Conal O'Grada, James Carty, Emer Mayock, Joanie Madden, Michael Tubridy and Catherine McEvoy, while whistlers include Paddy Moloney, Carmel Gunning, Paddy Keenan, Seán Ryan, Andrea Corr, Mary Bergin, Packie Byrne and Cormac Breatnach.Uilleann pipes (pronounced ill-in or ill-yun depending upon local dialect) are a complex instrument. Tradition holds that seven years learning, seven years practising and seven years playing is required before a piper could be said to have mastered his instrument. The uilleann pipes developed around the beginning of the 18th century, the history of which is depicted in carvings and pictures from contemporary sources in both Britain and Ireland as pastoraland union pipes. Its modern form had arrived by the end of the 18th century, and was played by gentlemen pipers such as the mid-18th century piper Jackson from Limerick and the Tandragee pipemaker William Kennedy, the Anglican clergyman Canon James Goodman (1828–1896) and his friend John Hingston from Skibbereen. These were followed in the 20th century by the likes of Séamus Ennis, Leo Rowsome and Willie Clancy, playing refined and ornate pieces, as well as showy, ornamented forms played by travelling pipers like John Cash and Johnny Doran.The uilleann piping tradition had nearly died before being re-popularized by the likes of Paddy Moloney (of the Chieftains), and the formation of Na Píobairí Uilleann, an organisation open to pipers that included such players as Rowsome and Ennis, as well as researcher and collector Breandán Breathnach. Liam O'Flynn is one of the most popular of modern performers along with Paddy Keenan, John McSherry, Davy Spillane, Jerry O'Sullivan, Mick O'Brien and many more. Many Pavee (Traveller) families, such as the Fureys and Dorans and Keenans, are famous for the pipers among them. Famous was also the McPeake Family, who toured Europe. Uilleann pipes are among the most complex forms of bagpipes; they possess a chanter with a double reed and a two-octave range, three single-reed drones, and, in the complete version known as a full set, a trio of (regulators) all with double reeds and keys worked by the piper's forearm, capable of providing harmonic support for the melody. (Virtually all uilleann pipers begin playing with a half set, lacking the regulators and consisting of only bellows, bag, chanter, and drones. Some choose never to play the full set, and many make little use of the regulators.) The bag is filled with air by a bellows held between the piper's elbow and side, rather than by the performer's lungs as in the highland pipes and almost all other forms of bagpipe, aside from the Scottish smallpipes, Pastoral pipes (which also plays with regulators), the Northumbrian pipes of northern England, and the Border pipes found in both parts of the Anglo-Scottish Border country. The uilleann pipes play a prominent part in a form of instrumental music called Fonn Mall, closely related to unaccompanied singing an sean nós ("in the old style"). Willie Clancy, Leo Rowsome, and Garret Barry were among the many pipers famous in their day; Paddy Keenan, Davy Spillane and Robbie Hannan play these traditional airs today, among many others. The harp is among the chief symbols of Ireland. The Celtic harp, seen on Irish coinage and used in Guinness advertising, was played as long ago as the 10th century. In ancient times, the harpers were greatly respected and, along with poets and scribes, assigned a high place amongst the most significant retainers of the old Gaelic order of lords and chieftains. Perhaps the best known representative of this tradition of harping today is Turlough Ó Carolan, a blind 18th century harper who is often considered the unofficial national composer of Ireland. Thomas Connellan, a slightly earlier Sligo harper, composed such well known airs as "The Dawning of the Day"/"Raglan Road" and "Carolan's Dream". The native Irish harping tradition was an aristocratic art music with its own canon and rules for arrangement and compositional structure, only tangentially associated with the folkloric music of the common people, the ancestor of present-day Irish traditional music. Some of the late exponents of the harping tradition, such as O'Carolan, were influenced by the Italian Baroque art music of such composers as Vivaldi, which could be heard in the theatres and concert halls of Dublin. The harping tradition did not long outlast the native Gaelic aristocracy which supported it. By the early 19th century, the Irish harp and its music were for all intents and purposes dead. Tunes from the harping tradition survived only as unharmonised melodies which had been picked up by the folkloric tradition, or were preserved as notated in collections such as Edward Bunting's, (he attended the Belfast Harp Festival in 1792) in which the tunes were most often modified to make them fit for the drawing room pianofortes of the Anglicised middle and upper classes. The first generations of 20th century revivalists, mostly playing the gut-strung (frequently replaced with nylon after the Second World War) neo-Celtic harp with the pads of their fingers rather than the old brass-strung harp plucked with long fingernails, tended to take the dance tunes and song airs of Irish traditional music, along with such old harp tunes as they could find, and applied to them techniques derived from the orchestral (pedal) harp and an approach to rhythm, arrangement, and tempo that often had more in common with mainstream classical music than with either the old harping tradition or the living tradition of Irish music. A separate Belfast tradition of harp-accompanied folk-singing was preserved by the McPeake Family. Over the past thirty years a revival of the early Irish harp has been growing, with replicas of the medieval instruments being played, using strings of brass, silver, and even gold. This revival grew through the work of a number of musicians including Arnold Dolmetsch in 1930s England, Alan Stivell in 1960s Brittany, and most importantly Ann Heymann in the US from the 1970s to the present. Notable players of the modern harp include Derek Bell (of The Chieftains), Laoise Kelly (of The Bumblebees), Gráinne Hambly, Máire Ní Chathasaigh, Mary O'Hara, Antoinette McKenna, Michael Rooney, Áine Minogue, Patrick Ball and Bonnie Shaljean. The best of these have a solid background in genuine Irish traditional music, often having strong competency on another instrument more common in the living tradition, such as the fiddle or concertina, and work very hard at adapting the harp to traditional music, as well as reconstructing what they can of the old harpers' music on the basis of the few manuscript sources which exist. However, the harp continues to occupy a place on the fringe of Irish traditional music. Liam O'Flynn playing uilleann pipes

Liam O'Flynn playing uilleann pipes The accordion plays a major part in modern Irish music. The accordion spread to Ireland late in the 19th century. In its ten-key form (melodeon), it is claimed that it was popular across the island. It was recorded in the US by John Kimmel, The Flanagan Brothers, Eddie Herborn and Peter Conlon. While uncommon, the melodeon is still played in some parts of Ireland, in particular in Connemara by Johnny Connolly. Modern Irish accordion players generally prefer the 2 row button accordion. Unlike similar accordions used in other European and American music traditions, the rows are tuned a semi-tone apart. This allows the instrument to be played chromatically in melody. Currently accordions tuned to the keys of B/C and C#/D are by far the most popular systems. The B/C accordion lends itself to a flowing style; it was popularised by Paddy O'Brien of Tipperary in the late 1940s and 1950s, Joe Burke and Sonny Brogan in the 1950s and 60s. Dublin native James Keane brought the instrument to New York where he maintained an influential recording and performing career from the 1970s to the present. Other famous B/C players include Paddy O'Brien of County Offaly, Bobby Gardiner, Finbarr Dwyer, John Nolan, James Keane, and Billy McComiskey. The C#/D accordion lends itself to a punchier style and is particularly popular in the slides and polkas of Kerry Music. Notable players include Tony MacMahon, Máirtín O'Connor, Sharon Shannon, Charlie Piggott, Jackie Daly, Joe Cooley and Johnny O'Leary. The piano accordion became highly popular during the 1950s and has flourished to the present day in céilí bands and for old time Irish dance music. Their greater range, ease of changing key, more fluent action, along with their strong musette tuning blended seamlessly with the other instruments and were highly valued during this period. They are the mainstay of the top Irish and Scottish ceilidh bands, including the County Antrim-based Haste to the Wedding Celidh Band, the Gallowglass Céilí Band, the Fitzgerald Céilí Band, Dermot O'Brien, Malachy Doris, Sean Quinn and Mick Foster are well known Irish solo masters of this instrument and were well recorded. The latest revival of traditional music from the late 1970s also revived the interest in this versatile instrument. Like the button key accordion, a new playing style has emerged with a dry tuning, lighter style of playing and a more rhythmically varied bass. The most notable players of this modern style are Karen Tweed (England) and Alan Kelly (Roscommon). Concertinas are manufactured in several types, the most common in Irish traditional music being the Anglo system with a few musicians now playing the English system. Each differs from the other in construction and playing technique. The most distinctive characteristic of the Anglo system is that each button sounds a different note, depending on whether the bellows are compressed or expanded. Anglo concertinas typically have either two or three rows of buttons that sound notes, plus an "air button" located near the right thumb that allows the player to fill or empty the bellows without sounding a note. Two-row Anglo concertinas usually have 20 buttons that sound notes. Each row of 10 buttons comprises notes within a common key. The two primary rows thus contain the notes of two musical keys, such as C and G. Each row is divided in two with five buttons playing lower-pitched notes of the given key on the left-hand end of the instrument and five buttons playing the higher pitched notes on the right-hand end. The row of buttons in the higher key is closer to the wrist of each hand. 20 key concertinas have a limited use for Irish traditional music due to the limited range of accidentals available. Three-row concertinas add a third row of accidentals (i.e., sharps and flats not included in the keys represented by the two main rows) and redundant notes (i.e., notes that duplicate those in the main keys but are located in the third, outermost row) that enable the instrument to be played in virtually any key. A series of sequential notes can be played in the home-key rows by depressing a button, compressing the bellows, depressing the same button and extending the bellows, moving to the next button and repeating the process, and so on. A consequence of this arrangement is that the player often encounters occasions requiring a change in bellows direction, which produces a clear separation between the sounds of the two adjacent notes. This tends to give the music a more punctuated, bouncy sound that can be especially well suited to hornpipes or jigs. English concertinas, by contrast, sound the same note for any given button, irrespective of the direction of bellows travel. Thus, any note can be played while the bellows is either expanded or compressed. As a consequence, sequential notes can be played without altering the bellows direction. This allows sequences of notes to be played in a smooth, continuous stream without the interruption of changing bellows direction. Despite the inherent bounciness of the Anglo and the inherent smoothness of the English concertina systems, skilled players of Irish traditional music can achieve either effect on each type of instrument by adapting the playing style. On the Anglo, for example, the notes on various rows partially overlap and the third row contains additional redundant notes, so that the same note can be sounded with more than one button. Often, whereas one button will sound a given note on bellows compression, an alternative button in a different row will sound the same note on bellows expansion. Thus, by playing across the rows, the player can avoid changes in bellows direction from note to note where the musical objective is a smoother sound. Likewise, the English system accommodates playing styles that counteract its inherent smoothness and continuity between notes. Specifically, when the music calls for it, the player can choose to reverse bellows direction, causing sequential notes to be more distinctly articulated. Popular concertina players include Niall Vallely, Kitty Hayes, Mícheál Ó Raghallaigh, Tim Collins, Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin, Mary MacNamara, Noel Hill, Kate McNamaraA girl playing an accordion on Saint Patrick's Day in Dublin, 2010

The accordion plays a major part in modern Irish music. The accordion spread to Ireland late in the 19th century. In its ten-key form (melodeon), it is claimed that it was popular across the island. It was recorded in the US by John Kimmel, The Flanagan Brothers, Eddie Herborn and Peter Conlon. While uncommon, the melodeon is still played in some parts of Ireland, in particular in Connemara by Johnny Connolly. Modern Irish accordion players generally prefer the 2 row button accordion. Unlike similar accordions used in other European and American music traditions, the rows are tuned a semi-tone apart. This allows the instrument to be played chromatically in melody. Currently accordions tuned to the keys of B/C and C#/D are by far the most popular systems. The B/C accordion lends itself to a flowing style; it was popularised by Paddy O'Brien of Tipperary in the late 1940s and 1950s, Joe Burke and Sonny Brogan in the 1950s and 60s. Dublin native James Keane brought the instrument to New York where he maintained an influential recording and performing career from the 1970s to the present. Other famous B/C players include Paddy O'Brien of County Offaly, Bobby Gardiner, Finbarr Dwyer, John Nolan, James Keane, and Billy McComiskey. The C#/D accordion lends itself to a punchier style and is particularly popular in the slides and polkas of Kerry Music. Notable players include Tony MacMahon, Máirtín O'Connor, Sharon Shannon, Charlie Piggott, Jackie Daly, Joe Cooley and Johnny O'Leary. The piano accordion became highly popular during the 1950s and has flourished to the present day in céilí bands and for old time Irish dance music. Their greater range, ease of changing key, more fluent action, along with their strong musette tuning blended seamlessly with the other instruments and were highly valued during this period. They are the mainstay of the top Irish and Scottish ceilidh bands, including the County Antrim-based Haste to the Wedding Celidh Band, the Gallowglass Céilí Band, the Fitzgerald Céilí Band, Dermot O'Brien, Malachy Doris, Sean Quinn and Mick Foster are well known Irish solo masters of this instrument and were well recorded. The latest revival of traditional music from the late 1970s also revived the interest in this versatile instrument. Like the button key accordion, a new playing style has emerged with a dry tuning, lighter style of playing and a more rhythmically varied bass. The most notable players of this modern style are Karen Tweed (England) and Alan Kelly (Roscommon). Concertinas are manufactured in several types, the most common in Irish traditional music being the Anglo system with a few musicians now playing the English system. Each differs from the other in construction and playing technique. The most distinctive characteristic of the Anglo system is that each button sounds a different note, depending on whether the bellows are compressed or expanded. Anglo concertinas typically have either two or three rows of buttons that sound notes, plus an "air button" located near the right thumb that allows the player to fill or empty the bellows without sounding a note. Two-row Anglo concertinas usually have 20 buttons that sound notes. Each row of 10 buttons comprises notes within a common key. The two primary rows thus contain the notes of two musical keys, such as C and G. Each row is divided in two with five buttons playing lower-pitched notes of the given key on the left-hand end of the instrument and five buttons playing the higher pitched notes on the right-hand end. The row of buttons in the higher key is closer to the wrist of each hand. 20 key concertinas have a limited use for Irish traditional music due to the limited range of accidentals available. Three-row concertinas add a third row of accidentals (i.e., sharps and flats not included in the keys represented by the two main rows) and redundant notes (i.e., notes that duplicate those in the main keys but are located in the third, outermost row) that enable the instrument to be played in virtually any key. A series of sequential notes can be played in the home-key rows by depressing a button, compressing the bellows, depressing the same button and extending the bellows, moving to the next button and repeating the process, and so on. A consequence of this arrangement is that the player often encounters occasions requiring a change in bellows direction, which produces a clear separation between the sounds of the two adjacent notes. This tends to give the music a more punctuated, bouncy sound that can be especially well suited to hornpipes or jigs. English concertinas, by contrast, sound the same note for any given button, irrespective of the direction of bellows travel. Thus, any note can be played while the bellows is either expanded or compressed. As a consequence, sequential notes can be played without altering the bellows direction. This allows sequences of notes to be played in a smooth, continuous stream without the interruption of changing bellows direction. Despite the inherent bounciness of the Anglo and the inherent smoothness of the English concertina systems, skilled players of Irish traditional music can achieve either effect on each type of instrument by adapting the playing style. On the Anglo, for example, the notes on various rows partially overlap and the third row contains additional redundant notes, so that the same note can be sounded with more than one button. Often, whereas one button will sound a given note on bellows compression, an alternative button in a different row will sound the same note on bellows expansion. Thus, by playing across the rows, the player can avoid changes in bellows direction from note to note where the musical objective is a smoother sound. Likewise, the English system accommodates playing styles that counteract its inherent smoothness and continuity between notes. Specifically, when the music calls for it, the player can choose to reverse bellows direction, causing sequential notes to be more distinctly articulated. Popular concertina players include Niall Vallely, Kitty Hayes, Mícheál Ó Raghallaigh, Tim Collins, Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin, Mary MacNamara, Noel Hill, Kate McNamaraA girl playing an accordion on Saint Patrick's Day in Dublin, 2010 -

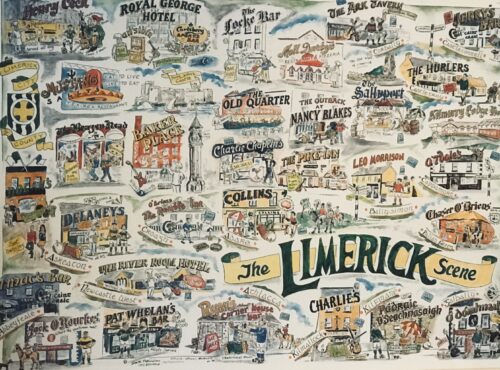

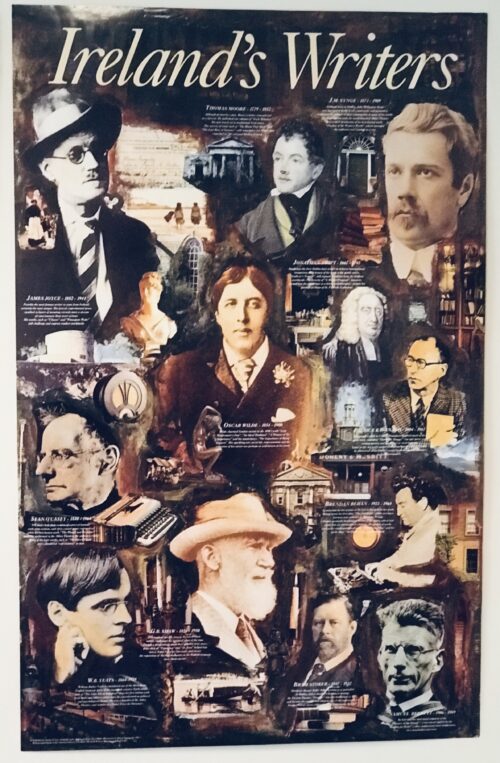

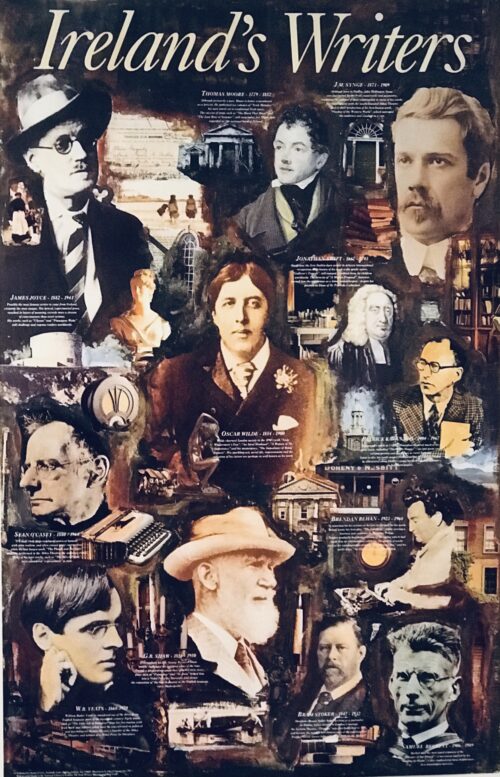

Superb poster depicting the myriad of Irish literary greats throughout the ages -to name but a few,Thomas Moore,JM Synge,WB Yeats,Joyce,Oscar Wilde,Patrick Kavanagh,G.B Shaw etc 84cm x 54cm Irish Literature comprises writings in the Irish, Latin, and English (including Ulster Scots) languages on the island of Ireland. The earliest recorded Irish writing dates from the seventh century and was produced by monks writing in both Latin and Early Irish. In addition to scriptural writing, the monks of Ireland recorded both poetry and mythological tales. There is a large surviving body of Irish mythological writing, including tales such as The Táin and Mad King Sweeny. The English language was introduced to Ireland in the thirteenth century, following the Norman invasion of Ireland. The Irish language, however, remained the dominant language of Irish literature down to the nineteenth century, despite a slow decline which began in the seventeenth century with the expansion of English power. The latter part of the nineteenth century saw a rapid replacement of Irish by English in the greater part of the country. At the end of the century, however, cultural nationalism displayed a new energy, marked by the Gaelic Revival(which encouraged a modern literature in Irish) and more generally by the Irish Literary Revival. The Anglo-Irish literary tradition found its first great exponents in Richard Head and Jonathan Swift followed by Laurence Sterne, Oliver Goldsmith and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. At the end of 19th century and throughout the 20th century, the Irish literature get an unprecedented sequence of worldwide successful works, especially those by Oscar Wilde, Bram Stoker, James Joyce, W. B. Yeats, Samuel Beckett, C.S. Lewis and George Bernard Shaw, prominent writers who left Ireland to make a life in other European countries such as England, France and Switzerland. The descendants of Scottish settlers in Ulster formed the Ulster-Scots writing tradition, having an especially strong tradition of rhyming poetry. Though English was the dominant Irish literary language in the twentieth century, much work of high quality appeared in Irish Gaelic. A pioneering modernist writer in Irish was Pádraic Ó Conaire, and traditional life was given vigorous expression in a series of autobiographies by native Irish speakers from the west coast, exemplified by the work of Tomás Ó Criomhthain and Peig Sayers. The outstanding modernist prose writer in Irish was Máirtín Ó Cadhain, and prominent poets included Máirtín Ó Direáin, Seán Ó Ríordáin and Máire Mhac an tSaoi. Prominent bilingual writers included Brendan Behan (who wrote poetry and a play in Irish) and Flann O'Brien. Two novels by O'Brien, At Swim Two Birdsand The Third Policeman, are considered early examples of postmodern fiction, but he also wrote a satirical novel in Irish called An Béal Bocht(translated as The Poor Mouth). Liam O'Flaherty, who gained fame as a writer in English, also published a book of short stories in Irish (Dúil). Most attention has been given to Irish writers who wrote in English and who were at the forefront of the modernist movement, notably James Joyce, whose novel Ulysses is considered one of the most influential of the century. The playwright Samuel Beckett, in addition to a large amount of prose fiction, wrote a number of important plays, including Waiting for Godot. Several Irish writers have excelled at short story writing, in particular Frank O'Connor and William Trevor. In the late twentieth century Irish poets, especially those from Northern Ireland, came to prominence with Derek Mahon, John Montague, Seamus Heaney and Paul Muldoon. Other notable Irish writers from the twentieth century include, poet Patrick Kavanagh, dramatists Tom Murphy and Brian Friel and novelists Edna O'Brien and John McGahern. Well-known Irish writers in English in the twenty-first century include Colum McCann, Anne Enright, Roddy Doyle, Sebastian Barry, Colm Toibín and John Banville, all of whom have all won major awards. Younger writers include Paul Murray, Kevin Barry, Emma Donoghue, Donal Ryan and dramatist Martin McDonagh. Writing in Irish has also continued to flourish. Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 90cm x 60cm 8kg

Superb poster depicting the myriad of Irish literary greats throughout the ages -to name but a few,Thomas Moore,JM Synge,WB Yeats,Joyce,Oscar Wilde,Patrick Kavanagh,G.B Shaw etc 84cm x 54cm Irish Literature comprises writings in the Irish, Latin, and English (including Ulster Scots) languages on the island of Ireland. The earliest recorded Irish writing dates from the seventh century and was produced by monks writing in both Latin and Early Irish. In addition to scriptural writing, the monks of Ireland recorded both poetry and mythological tales. There is a large surviving body of Irish mythological writing, including tales such as The Táin and Mad King Sweeny. The English language was introduced to Ireland in the thirteenth century, following the Norman invasion of Ireland. The Irish language, however, remained the dominant language of Irish literature down to the nineteenth century, despite a slow decline which began in the seventeenth century with the expansion of English power. The latter part of the nineteenth century saw a rapid replacement of Irish by English in the greater part of the country. At the end of the century, however, cultural nationalism displayed a new energy, marked by the Gaelic Revival(which encouraged a modern literature in Irish) and more generally by the Irish Literary Revival. The Anglo-Irish literary tradition found its first great exponents in Richard Head and Jonathan Swift followed by Laurence Sterne, Oliver Goldsmith and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. At the end of 19th century and throughout the 20th century, the Irish literature get an unprecedented sequence of worldwide successful works, especially those by Oscar Wilde, Bram Stoker, James Joyce, W. B. Yeats, Samuel Beckett, C.S. Lewis and George Bernard Shaw, prominent writers who left Ireland to make a life in other European countries such as England, France and Switzerland. The descendants of Scottish settlers in Ulster formed the Ulster-Scots writing tradition, having an especially strong tradition of rhyming poetry. Though English was the dominant Irish literary language in the twentieth century, much work of high quality appeared in Irish Gaelic. A pioneering modernist writer in Irish was Pádraic Ó Conaire, and traditional life was given vigorous expression in a series of autobiographies by native Irish speakers from the west coast, exemplified by the work of Tomás Ó Criomhthain and Peig Sayers. The outstanding modernist prose writer in Irish was Máirtín Ó Cadhain, and prominent poets included Máirtín Ó Direáin, Seán Ó Ríordáin and Máire Mhac an tSaoi. Prominent bilingual writers included Brendan Behan (who wrote poetry and a play in Irish) and Flann O'Brien. Two novels by O'Brien, At Swim Two Birdsand The Third Policeman, are considered early examples of postmodern fiction, but he also wrote a satirical novel in Irish called An Béal Bocht(translated as The Poor Mouth). Liam O'Flaherty, who gained fame as a writer in English, also published a book of short stories in Irish (Dúil). Most attention has been given to Irish writers who wrote in English and who were at the forefront of the modernist movement, notably James Joyce, whose novel Ulysses is considered one of the most influential of the century. The playwright Samuel Beckett, in addition to a large amount of prose fiction, wrote a number of important plays, including Waiting for Godot. Several Irish writers have excelled at short story writing, in particular Frank O'Connor and William Trevor. In the late twentieth century Irish poets, especially those from Northern Ireland, came to prominence with Derek Mahon, John Montague, Seamus Heaney and Paul Muldoon. Other notable Irish writers from the twentieth century include, poet Patrick Kavanagh, dramatists Tom Murphy and Brian Friel and novelists Edna O'Brien and John McGahern. Well-known Irish writers in English in the twenty-first century include Colum McCann, Anne Enright, Roddy Doyle, Sebastian Barry, Colm Toibín and John Banville, all of whom have all won major awards. Younger writers include Paul Murray, Kevin Barry, Emma Donoghue, Donal Ryan and dramatist Martin McDonagh. Writing in Irish has also continued to flourish. Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 90cm x 60cm 8kg -

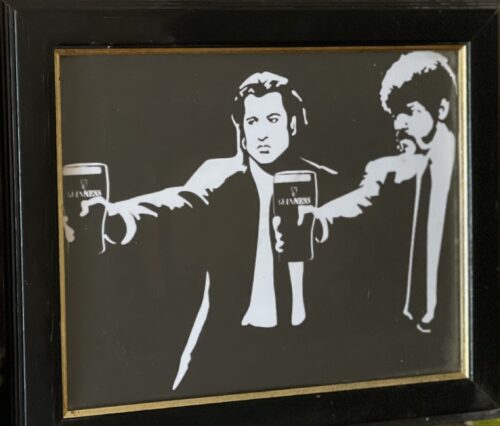

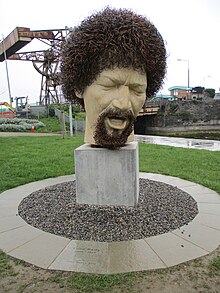

55cm x 45cm Luke Kelly (17 November 1940 – 30 January 1984) was an Irish singer, folk musician and actor from Dublin, Ireland. Born into a working-class household in Dublin city, Kelly moved to England in his late teens and by his early 20s had become involved in a folk music revival. Returning to Dublin in the 1960s, he is noted as a founding member of the band The Dubliners in 1962. Becoming known for his distinctive singing style, and sometimes political messages, the Irish Postand other commentators have regarded Kelly as one of Ireland's greatest folk singers. Early life Luke Kelly was born into a working-class family in Lattimore Cottages at 1 Sheriff Street.His maternal grandmother, who was a MacDonald from Scotland, lived with the family until her death in 1953. His father who was Irish- also named Luke- was shot and severely wounded as a child by British soldiers from the King's Own Scottish Borderers during the 1914 Bachelor's Walk massacre.His father worked all his life in Jacob's biscuit factory and enjoyed playing football. The elder Luke was a keen singer: Luke junior's brother Paddy later recalled that "he had this talent... to sing negro spirituals by people like Paul Robeson, we used to sit around and join in — that was our entertainment". After Dublin Corporation demolished Lattimore Cottages in 1942, the Kellys became the first family to move into the St. Laurence O’Toole flats, where Luke spent the bulk of his childhood, although the family were forced to move by a fire in 1953 and settled in the Whitehall area. Both Luke and Paddy played club Gaelic football and soccer as children. Kelly left school at thirteen and after a number of years of odd-jobbing, he went to England in 1958.[6] Working at steel fixing with his brother Paddy on a building site in Wolverhampton, he was apparently sacked after asking for higher pay. He worked a number of odd jobs, including a period as a vacuum cleaner salesman.Describing himself as a beatnik, he travelled Northern England in search of work, summarising his life in this period as "cleaning lavatories, cleaning windows, cleaning railways, but very rarely cleaning my face".

55cm x 45cm Luke Kelly (17 November 1940 – 30 January 1984) was an Irish singer, folk musician and actor from Dublin, Ireland. Born into a working-class household in Dublin city, Kelly moved to England in his late teens and by his early 20s had become involved in a folk music revival. Returning to Dublin in the 1960s, he is noted as a founding member of the band The Dubliners in 1962. Becoming known for his distinctive singing style, and sometimes political messages, the Irish Postand other commentators have regarded Kelly as one of Ireland's greatest folk singers. Early life Luke Kelly was born into a working-class family in Lattimore Cottages at 1 Sheriff Street.His maternal grandmother, who was a MacDonald from Scotland, lived with the family until her death in 1953. His father who was Irish- also named Luke- was shot and severely wounded as a child by British soldiers from the King's Own Scottish Borderers during the 1914 Bachelor's Walk massacre.His father worked all his life in Jacob's biscuit factory and enjoyed playing football. The elder Luke was a keen singer: Luke junior's brother Paddy later recalled that "he had this talent... to sing negro spirituals by people like Paul Robeson, we used to sit around and join in — that was our entertainment". After Dublin Corporation demolished Lattimore Cottages in 1942, the Kellys became the first family to move into the St. Laurence O’Toole flats, where Luke spent the bulk of his childhood, although the family were forced to move by a fire in 1953 and settled in the Whitehall area. Both Luke and Paddy played club Gaelic football and soccer as children. Kelly left school at thirteen and after a number of years of odd-jobbing, he went to England in 1958.[6] Working at steel fixing with his brother Paddy on a building site in Wolverhampton, he was apparently sacked after asking for higher pay. He worked a number of odd jobs, including a period as a vacuum cleaner salesman.Describing himself as a beatnik, he travelled Northern England in search of work, summarising his life in this period as "cleaning lavatories, cleaning windows, cleaning railways, but very rarely cleaning my face".Musical beginnings

Kelly had been interested in music during his teenage years: he regularly attended céilithe with his sister Mona and listened to American vocalists including: Fats Domino, Al Jolson, Frank Sinatra and Perry Como. He also had an interest in theatre and musicals, being involved with the staging of plays by Dublin's Marian Arts Society. The first folk club he came across was in the Bridge Hotel, Newcastle upon Tyne in early 1960.Having already acquired the use of a banjo, he started memorising songs. In Leeds he brought his banjo to sessions in McReady's pub. The folk revival was under way in England: at the centre of it was Ewan MacColl who scripted a radio programme called Ballads and Blues. A revival in the skiffle genre also injected a certain energy into folk singing at the time. Kelly started busking. On a trip home he went to a fleadh cheoil in Milltown Malbay on the advice of Johnny Moynihan. He listened to recordings of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. He also developed his political convictions which, as Ronnie Drew pointed out after his death, he stuck to throughout his life. As Drew also pointed out, he "learned to sing with perfect diction". Kelly befriended Sean Mulready in Birmingham and lived in his home for a period.Mulready was a teacher who was forced from his job in Dublin because of his communist beliefs. Mulready had strong music links; a sister, Kathleen Moynihan was a founder member of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, and he was related by marriage to Festy Conlon, the County Galway whistle player. Mulready's brother-in-law, Ned Stapleton, taught Kelly "The Rocky Road to Dublin".During this period he studied literature and politics under the tutelage of Mulready, his wife Mollie, and Marxist classicist George Derwent Thomson: Kelly later stated that his interest in music grew parallel to his interest in politics. Kelly bought his first banjo, which had five strings and a long neck, and played it in the style of Pete Seeger and Tommy Makem. At the same time, Kelly began a habit of reading, and also began playing golf on one of Birmingham's municipal courses. He got involved in the Jug O'Punch folk club run by Ian Campbell. He befriended Dominic Behan and they performed in folk clubs and Irish pubs from London to Glasgow. In London pubs, like "The Favourite", he would hear street singer Margaret Barry and musicians in exile like Roger Sherlock, Seamus Ennis, Bobby Casey and Mairtín Byrnes. Luke Kelly was by now active in the Connolly Association, a left-wing grouping strongest among the emigres in England, and he also joined the Young Communist League: he toured Irish pubs playing his set and selling the Connolly Association's newspaper The Irish Democrat. By 1962 George Derwent Thomson had offered him the opportunity to further his educational and political development by attending university in Prague. However, Kelly turned down the offer in favour of pursuing his career in folk music. He was also to start frequenting Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger's Singer Club in London.The Dubliners