-

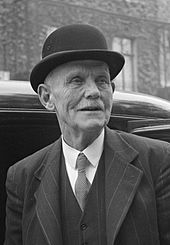

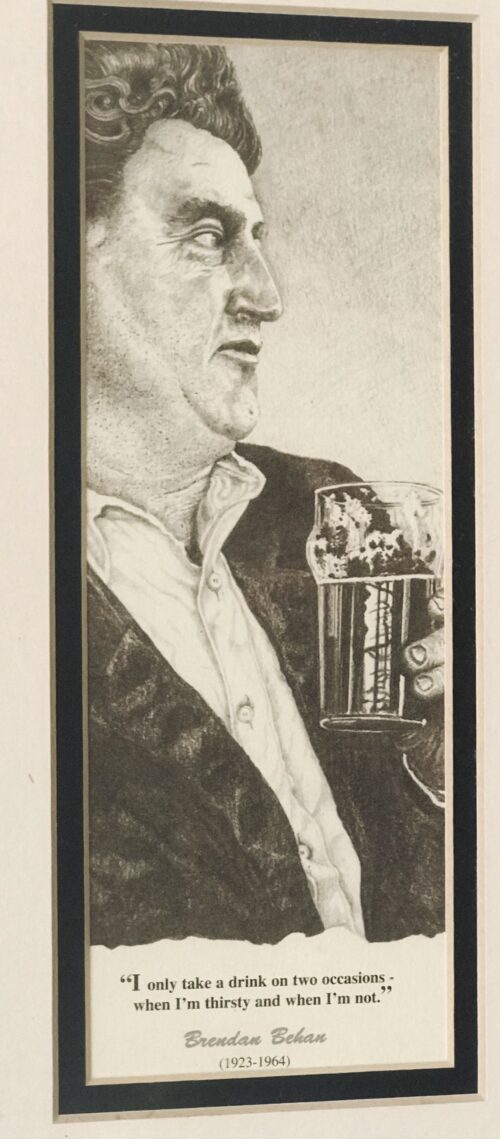

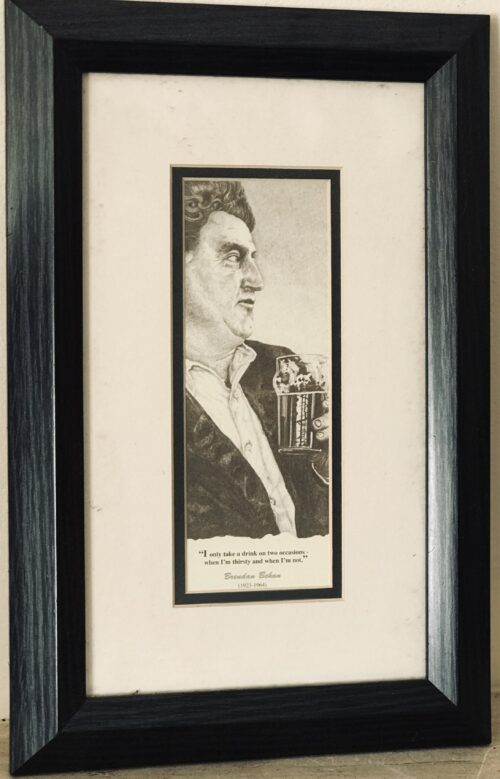

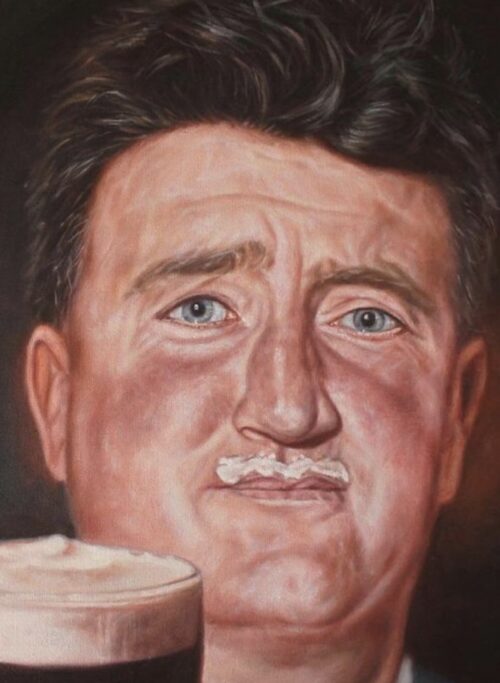

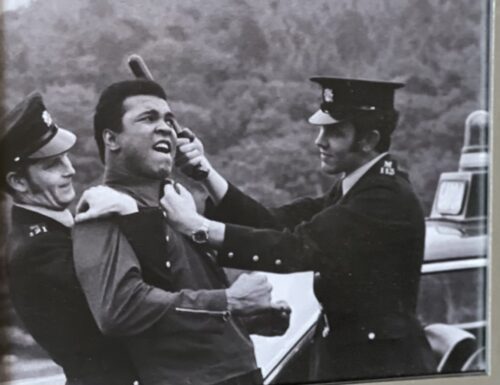

Humorous sketch of the enigmatic genius Brendan Began with typical irreverent quote attached. 37.5cm x 25.5cm Dublin BRENDAN BEHAN 1923-1964 PLAYWRIGHT AND AUTHOR Behan was born in Dublin on 9 February 1923. His father was a house painter who had been imprisoned as a republican towards the end of the Civil War, and from an early age Behan was steeped in Irish history and patriotic ballads; however, there was also a strong literary and cultural atmosphere in his home. At fourteen Behan was apprenticed to his father's trade. He was already a member of Fianna Éireann, the youth organisation of the Irish Republican Army, and a contributor to The United Irishman. When the IRA launched a bombing campaign in England in 1939, Behan was trained in explosives, but was arrested the day he landed in Liverpool. In February 1940 he was sentenced to three years' Borstal detention. He spent two years in a Borstal in Suffolk, making good use of its excellent library. In 1942, back in Dublin, Behan fired at a detective during an IRA parade and was sentenced to fourteen years' penal servitude. Again he broadened his education, becoming a fluent Irish speaker. During his first months in Mountjoy prison, Sean O Faolain published Behan's description of his Borstal experiences in The Bell. Behan was released in 1946 as part of a general amnesty and returned to painting. He would serve other prison terms, either for republican activity or as a result of his drinking, but none of such length. For some years Behan concentrated on writing verse in Irish. He lived in Paris for a time before returning in 1950 to Dublin, where he cultivated his reputation as one of the more rambunctious figures in the city's literary circles. In 1954 Behan's play The Quare Fellow was well received in the tiny Pike Theatre. However, it was the 1956 production at Joan Littlewood's Theatre Royal in Stratford, East London, that brought Behan a wider reputation - significantly assisted by a drunken interview on BBC television. Thereafter, Behan was never free from media attention, and he in turn was usually ready to play the drunken Irlshman. The 'quare fellow', never seen on stage, is a condemned man in prison. His imminent execution touches the lives of the other prisoners, the warders and the hangman, and the play is in part a protest against capital punishment. More important, though, its blend of tragedy and comedy underlines the survival of the prisoners' humanity in their inhumane environment. How much the broader London version owed to Joan Littlewood is a matter of debate. Comparing him with another alcoholic writer, Dylan Thomas, a friend said that 'Dylan wrote Under Milkwood and Brendan wrote under Littlewood'. Behan's second play, An Giall (1958), was commissioned by Gael Linn, the Irish-language organisation. Behan translated the play into English and it was Joan Littlewood's production of The Hostage (1958) which led to success in London and New York. As before Behan's tragi-comedy deals with a closed world, in this case a Dublin brothel where the IRA imprison an English soldier, but Littlewood diluted the naturalism of the Irish version with interludes of music-hall singing and dancing. Behan's autobiographical Borstal Boy also appeared in 1958, and its early chapters on prison life are among his best work. By then, however, he was a victim of his own celebrity, and alcoholism and diabetes were taking their toll. His English publishers suggested that, instead of the writing he now found difficult, he dictate to a tape recorder. The first outcome was Brendan Behan's Island (1962), a readable collection of anecdotes and opinions in which it was apparent that Behan had moved away from the republican extremism of his youth. Tape-recording also produced Brendan Behan's New York(1964) and Confessions of an Irish Rebel (1965), a disappointing sequel to Borstal Boy. A collection of newspaper columns from the l950s, published as Hold Your Hour and Have Another (1963), merely underlined the inferiority of his later work. When Behan died in Dublin on 20 March 1964, an IRA guard of honour escorted his coffin. One newspaper described it as the biggest funeral since those of Michael Collins and Charles Stewart Parnell.

Humorous sketch of the enigmatic genius Brendan Began with typical irreverent quote attached. 37.5cm x 25.5cm Dublin BRENDAN BEHAN 1923-1964 PLAYWRIGHT AND AUTHOR Behan was born in Dublin on 9 February 1923. His father was a house painter who had been imprisoned as a republican towards the end of the Civil War, and from an early age Behan was steeped in Irish history and patriotic ballads; however, there was also a strong literary and cultural atmosphere in his home. At fourteen Behan was apprenticed to his father's trade. He was already a member of Fianna Éireann, the youth organisation of the Irish Republican Army, and a contributor to The United Irishman. When the IRA launched a bombing campaign in England in 1939, Behan was trained in explosives, but was arrested the day he landed in Liverpool. In February 1940 he was sentenced to three years' Borstal detention. He spent two years in a Borstal in Suffolk, making good use of its excellent library. In 1942, back in Dublin, Behan fired at a detective during an IRA parade and was sentenced to fourteen years' penal servitude. Again he broadened his education, becoming a fluent Irish speaker. During his first months in Mountjoy prison, Sean O Faolain published Behan's description of his Borstal experiences in The Bell. Behan was released in 1946 as part of a general amnesty and returned to painting. He would serve other prison terms, either for republican activity or as a result of his drinking, but none of such length. For some years Behan concentrated on writing verse in Irish. He lived in Paris for a time before returning in 1950 to Dublin, where he cultivated his reputation as one of the more rambunctious figures in the city's literary circles. In 1954 Behan's play The Quare Fellow was well received in the tiny Pike Theatre. However, it was the 1956 production at Joan Littlewood's Theatre Royal in Stratford, East London, that brought Behan a wider reputation - significantly assisted by a drunken interview on BBC television. Thereafter, Behan was never free from media attention, and he in turn was usually ready to play the drunken Irlshman. The 'quare fellow', never seen on stage, is a condemned man in prison. His imminent execution touches the lives of the other prisoners, the warders and the hangman, and the play is in part a protest against capital punishment. More important, though, its blend of tragedy and comedy underlines the survival of the prisoners' humanity in their inhumane environment. How much the broader London version owed to Joan Littlewood is a matter of debate. Comparing him with another alcoholic writer, Dylan Thomas, a friend said that 'Dylan wrote Under Milkwood and Brendan wrote under Littlewood'. Behan's second play, An Giall (1958), was commissioned by Gael Linn, the Irish-language organisation. Behan translated the play into English and it was Joan Littlewood's production of The Hostage (1958) which led to success in London and New York. As before Behan's tragi-comedy deals with a closed world, in this case a Dublin brothel where the IRA imprison an English soldier, but Littlewood diluted the naturalism of the Irish version with interludes of music-hall singing and dancing. Behan's autobiographical Borstal Boy also appeared in 1958, and its early chapters on prison life are among his best work. By then, however, he was a victim of his own celebrity, and alcoholism and diabetes were taking their toll. His English publishers suggested that, instead of the writing he now found difficult, he dictate to a tape recorder. The first outcome was Brendan Behan's Island (1962), a readable collection of anecdotes and opinions in which it was apparent that Behan had moved away from the republican extremism of his youth. Tape-recording also produced Brendan Behan's New York(1964) and Confessions of an Irish Rebel (1965), a disappointing sequel to Borstal Boy. A collection of newspaper columns from the l950s, published as Hold Your Hour and Have Another (1963), merely underlined the inferiority of his later work. When Behan died in Dublin on 20 March 1964, an IRA guard of honour escorted his coffin. One newspaper described it as the biggest funeral since those of Michael Collins and Charles Stewart Parnell. -

Humorous sketch of the enigmatic genius Brendan Began with typical irreverent quote attached. 37.5cm x 25.5cm Dublin BRENDAN BEHAN 1923-1964 PLAYWRIGHT AND AUTHOR Behan was born in Dublin on 9 February 1923. His father was a house painter who had been imprisoned as a republican towards the end of the Civil War, and from an early age Behan was steeped in Irish history and patriotic ballads; however, there was also a strong literary and cultural atmosphere in his home. At fourteen Behan was apprenticed to his father's trade. He was already a member of Fianna Éireann, the youth organisation of the Irish Republican Army, and a contributor to The United Irishman. When the IRA launched a bombing campaign in England in 1939, Behan was trained in explosives, but was arrested the day he landed in Liverpool. In February 1940 he was sentenced to three years' Borstal detention. He spent two years in a Borstal in Suffolk, making good use of its excellent library. In 1942, back in Dublin, Behan fired at a detective during an IRA parade and was sentenced to fourteen years' penal servitude. Again he broadened his education, becoming a fluent Irish speaker. During his first months in Mountjoy prison, Sean O Faolain published Behan's description of his Borstal experiences in The Bell. Behan was released in 1946 as part of a general amnesty and returned to painting. He would serve other prison terms, either for republican activity or as a result of his drinking, but none of such length. For some years Behan concentrated on writing verse in Irish. He lived in Paris for a time before returning in 1950 to Dublin, where he cultivated his reputation as one of the more rambunctious figures in the city's literary circles. In 1954 Behan's play The Quare Fellow was well received in the tiny Pike Theatre. However, it was the 1956 production at Joan Littlewood's Theatre Royal in Stratford, East London, that brought Behan a wider reputation - significantly assisted by a drunken interview on BBC television. Thereafter, Behan was never free from media attention, and he in turn was usually ready to play the drunken Irlshman. The 'quare fellow', never seen on stage, is a condemned man in prison. His imminent execution touches the lives of the other prisoners, the warders and the hangman, and the play is in part a protest against capital punishment. More important, though, its blend of tragedy and comedy underlines the survival of the prisoners' humanity in their inhumane environment. How much the broader London version owed to Joan Littlewood is a matter of debate. Comparing him with another alcoholic writer, Dylan Thomas, a friend said that 'Dylan wrote Under Milkwood and Brendan wrote under Littlewood'. Behan's second play, An Giall (1958), was commissioned by Gael Linn, the Irish-language organisation. Behan translated the play into English and it was Joan Littlewood's production of The Hostage (1958) which led to success in London and New York. As before Behan's tragi-comedy deals with a closed world, in this case a Dublin brothel where the IRA imprison an English soldier, but Littlewood diluted the naturalism of the Irish version with interludes of music-hall singing and dancing. Behan's autobiographical Borstal Boy also appeared in 1958, and its early chapters on prison life are among his best work. By then, however, he was a victim of his own celebrity, and alcoholism and diabetes were taking their toll. His English publishers suggested that, instead of the writing he now found difficult, he dictate to a tape recorder. The first outcome was Brendan Behan's Island (1962), a readable collection of anecdotes and opinions in which it was apparent that Behan had moved away from the republican extremism of his youth. Tape-recording also produced Brendan Behan's New York(1964) and Confessions of an Irish Rebel (1965), a disappointing sequel to Borstal Boy. A collection of newspaper columns from the l950s, published as Hold Your Hour and Have Another (1963), merely underlined the inferiority of his later work. When Behan died in Dublin on 20 March 1964, an IRA guard of honour escorted his coffin. One newspaper described it as the biggest funeral since those of Michael Collins and Charles Stewart Parnell.

Humorous sketch of the enigmatic genius Brendan Began with typical irreverent quote attached. 37.5cm x 25.5cm Dublin BRENDAN BEHAN 1923-1964 PLAYWRIGHT AND AUTHOR Behan was born in Dublin on 9 February 1923. His father was a house painter who had been imprisoned as a republican towards the end of the Civil War, and from an early age Behan was steeped in Irish history and patriotic ballads; however, there was also a strong literary and cultural atmosphere in his home. At fourteen Behan was apprenticed to his father's trade. He was already a member of Fianna Éireann, the youth organisation of the Irish Republican Army, and a contributor to The United Irishman. When the IRA launched a bombing campaign in England in 1939, Behan was trained in explosives, but was arrested the day he landed in Liverpool. In February 1940 he was sentenced to three years' Borstal detention. He spent two years in a Borstal in Suffolk, making good use of its excellent library. In 1942, back in Dublin, Behan fired at a detective during an IRA parade and was sentenced to fourteen years' penal servitude. Again he broadened his education, becoming a fluent Irish speaker. During his first months in Mountjoy prison, Sean O Faolain published Behan's description of his Borstal experiences in The Bell. Behan was released in 1946 as part of a general amnesty and returned to painting. He would serve other prison terms, either for republican activity or as a result of his drinking, but none of such length. For some years Behan concentrated on writing verse in Irish. He lived in Paris for a time before returning in 1950 to Dublin, where he cultivated his reputation as one of the more rambunctious figures in the city's literary circles. In 1954 Behan's play The Quare Fellow was well received in the tiny Pike Theatre. However, it was the 1956 production at Joan Littlewood's Theatre Royal in Stratford, East London, that brought Behan a wider reputation - significantly assisted by a drunken interview on BBC television. Thereafter, Behan was never free from media attention, and he in turn was usually ready to play the drunken Irlshman. The 'quare fellow', never seen on stage, is a condemned man in prison. His imminent execution touches the lives of the other prisoners, the warders and the hangman, and the play is in part a protest against capital punishment. More important, though, its blend of tragedy and comedy underlines the survival of the prisoners' humanity in their inhumane environment. How much the broader London version owed to Joan Littlewood is a matter of debate. Comparing him with another alcoholic writer, Dylan Thomas, a friend said that 'Dylan wrote Under Milkwood and Brendan wrote under Littlewood'. Behan's second play, An Giall (1958), was commissioned by Gael Linn, the Irish-language organisation. Behan translated the play into English and it was Joan Littlewood's production of The Hostage (1958) which led to success in London and New York. As before Behan's tragi-comedy deals with a closed world, in this case a Dublin brothel where the IRA imprison an English soldier, but Littlewood diluted the naturalism of the Irish version with interludes of music-hall singing and dancing. Behan's autobiographical Borstal Boy also appeared in 1958, and its early chapters on prison life are among his best work. By then, however, he was a victim of his own celebrity, and alcoholism and diabetes were taking their toll. His English publishers suggested that, instead of the writing he now found difficult, he dictate to a tape recorder. The first outcome was Brendan Behan's Island (1962), a readable collection of anecdotes and opinions in which it was apparent that Behan had moved away from the republican extremism of his youth. Tape-recording also produced Brendan Behan's New York(1964) and Confessions of an Irish Rebel (1965), a disappointing sequel to Borstal Boy. A collection of newspaper columns from the l950s, published as Hold Your Hour and Have Another (1963), merely underlined the inferiority of his later work. When Behan died in Dublin on 20 March 1964, an IRA guard of honour escorted his coffin. One newspaper described it as the biggest funeral since those of Michael Collins and Charles Stewart Parnell. -

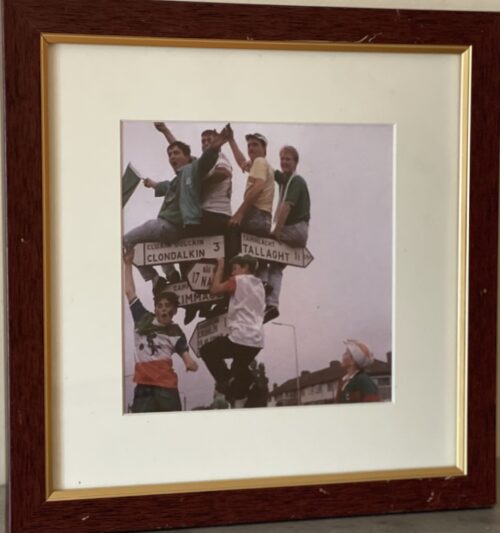

30cm x 30cm If ever a time symbolised flag-waving, delirious, green white and orange national pride, Italia '90 was that time. It all came down to one single glorious moment on a steamy June night in the Stadio Luigi Ferraris in Genoa when Packie Bonner saved that penalty and a deafening Une Voce roar erupted, ricocheting through every home and bar across Ireland. Seconds later when David O'Leary's winning penalty unleashed tears of unbridled joy Irish tricolours billowed like crazy in the breezeless stands and cascaded from the terraces to seemingly endless choruses of 'Olé, Olé, Olé, Olé'. We had made it through to the quarter-finals of the World Cup but we might as well have won and no-one wanted to let that moment go. Back home, cars catapulted onto the streets of every town and village with horns honking and flags wavering precariously from rolled-down windows. In Donegal an impromptu motorcade, suddenly, impulsively headed for Packie's home place in the Rosses, where fans danced in the front garden and waved the tricolour. It was an epic display of patriotic fervour and a defining moment, not just for Irish football but for our sense of identity. Historian and author, John Dorney describes it as the moment when Irish identity and international football collided. In his analysis of the era, he concludes that the Irish team's English manager, Jack Charlton neither knew nor cared about the multiple divisions in Irish society. Likewise, many of the team had been born in England of Irish ancestry and were "a clean slate" without baggage.

30cm x 30cm If ever a time symbolised flag-waving, delirious, green white and orange national pride, Italia '90 was that time. It all came down to one single glorious moment on a steamy June night in the Stadio Luigi Ferraris in Genoa when Packie Bonner saved that penalty and a deafening Une Voce roar erupted, ricocheting through every home and bar across Ireland. Seconds later when David O'Leary's winning penalty unleashed tears of unbridled joy Irish tricolours billowed like crazy in the breezeless stands and cascaded from the terraces to seemingly endless choruses of 'Olé, Olé, Olé, Olé'. We had made it through to the quarter-finals of the World Cup but we might as well have won and no-one wanted to let that moment go. Back home, cars catapulted onto the streets of every town and village with horns honking and flags wavering precariously from rolled-down windows. In Donegal an impromptu motorcade, suddenly, impulsively headed for Packie's home place in the Rosses, where fans danced in the front garden and waved the tricolour. It was an epic display of patriotic fervour and a defining moment, not just for Irish football but for our sense of identity. Historian and author, John Dorney describes it as the moment when Irish identity and international football collided. In his analysis of the era, he concludes that the Irish team's English manager, Jack Charlton neither knew nor cared about the multiple divisions in Irish society. Likewise, many of the team had been born in England of Irish ancestry and were "a clean slate" without baggage. -

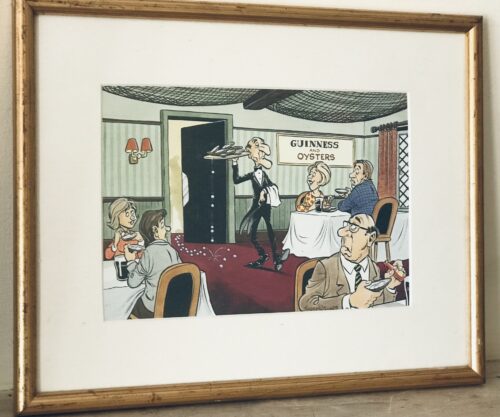

30cm x 39cm. Gort Co Galway Terry Willers was a famous cartoonist and animator.Born in England in 1935 he later moved to Co Wicklow and worked extensively for the Irish Times and other publications and magazines and also on RTE. In 1992 he founded the Guinness International Cartoon Festival in Rathdrum Co Wicklow. He also won the Jacobs award for his work in Television. He died in 2011. Guinness were an original sponsor of the Galway International Oyster Festival . The Galway International Oyster Festival is a food festival held annually in Galway on the west coast of Ireland on the last weekend of September, the first month of the oyster season. Inaugurated in 1954, it was the brainchild of the Great Southern Hotel (now Hotel Meyrick) manager, Brian Collins. In 2000 was described by the Sunday Times as "one of the 12 greatest shows on earth" and was listed in the 1987 AA Travel Guide as one of Europe's Seven Best Festivals. The Galway International Oyster Festival was created to celebrate the Galway Native Oyster as it is a unique feature of Galway City & County. Hotel Manager, Brian Collins had been searching for something unique to attract more visitors to Galway in what was then, a quieter month of the year. Collins discussed the idea with the folk at Guinness and Patrick M. Burke's Bar in Clarenbridge and the first Galway Oyster Festival was created in 1954 with a whole 34 attendees. The festival was originally held in Clarenbridge village during the day and the Great Southern Hotel in Galway City at night until the mid-1980s when it grew so large, all of the festivities were held in the city centre of Galway. There was a red & white striped marquee at Spanish Arch and then at Nimmo's Pier by the Claddagh. In order to reduce ticket prices, the festival changed location to The Radisson Hotel Galway in 2009 but due to popular demand, the marquee was brought back in 2011, located in the Docks and the festival was renamed as the Galway International Oyster & Seafood Festival. In 2014, the 60th anniversary of the event, its producers, Milestone Inventive, brought it back to its original Galway City home at the aptly named Fishmarket at the Spanish Arch. The main events are two Oyster Opening Championships, the Irish Oyster Opening Championship and the World Oyster Opening Championship.Other events include a Masquerade Gala 'Mardi-Gras', a seafood trail, a silent disco and a family day featuring everything from cookery demonstrations, to jazz, to circus skills workshops.

30cm x 39cm. Gort Co Galway Terry Willers was a famous cartoonist and animator.Born in England in 1935 he later moved to Co Wicklow and worked extensively for the Irish Times and other publications and magazines and also on RTE. In 1992 he founded the Guinness International Cartoon Festival in Rathdrum Co Wicklow. He also won the Jacobs award for his work in Television. He died in 2011. Guinness were an original sponsor of the Galway International Oyster Festival . The Galway International Oyster Festival is a food festival held annually in Galway on the west coast of Ireland on the last weekend of September, the first month of the oyster season. Inaugurated in 1954, it was the brainchild of the Great Southern Hotel (now Hotel Meyrick) manager, Brian Collins. In 2000 was described by the Sunday Times as "one of the 12 greatest shows on earth" and was listed in the 1987 AA Travel Guide as one of Europe's Seven Best Festivals. The Galway International Oyster Festival was created to celebrate the Galway Native Oyster as it is a unique feature of Galway City & County. Hotel Manager, Brian Collins had been searching for something unique to attract more visitors to Galway in what was then, a quieter month of the year. Collins discussed the idea with the folk at Guinness and Patrick M. Burke's Bar in Clarenbridge and the first Galway Oyster Festival was created in 1954 with a whole 34 attendees. The festival was originally held in Clarenbridge village during the day and the Great Southern Hotel in Galway City at night until the mid-1980s when it grew so large, all of the festivities were held in the city centre of Galway. There was a red & white striped marquee at Spanish Arch and then at Nimmo's Pier by the Claddagh. In order to reduce ticket prices, the festival changed location to The Radisson Hotel Galway in 2009 but due to popular demand, the marquee was brought back in 2011, located in the Docks and the festival was renamed as the Galway International Oyster & Seafood Festival. In 2014, the 60th anniversary of the event, its producers, Milestone Inventive, brought it back to its original Galway City home at the aptly named Fishmarket at the Spanish Arch. The main events are two Oyster Opening Championships, the Irish Oyster Opening Championship and the World Oyster Opening Championship.Other events include a Masquerade Gala 'Mardi-Gras', a seafood trail, a silent disco and a family day featuring everything from cookery demonstrations, to jazz, to circus skills workshops. -

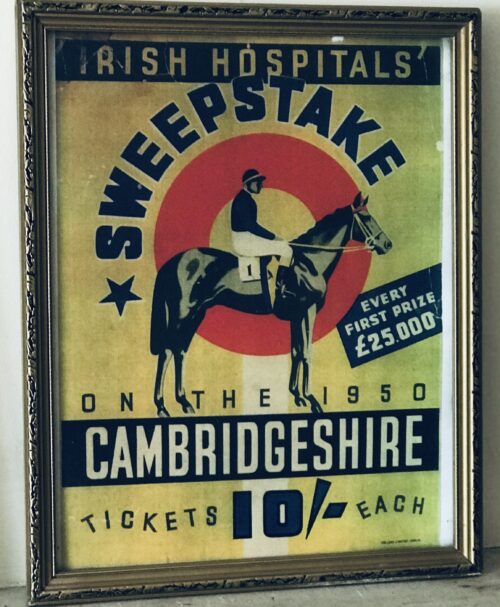

Fine print advertising the 1950 Irish Hospital Sweepstake for the horserace ,the Irish Cambridgeshire Handicap. The Irish Hospital Sweepstake was a lottery established in the Irish Free State in 1930 as the Irish Free State Hospitals' Sweepstake to finance hospitals. It is generally referred to as the Irish Sweepstake, frequently abbreviated to Irish Sweeps or Irish Sweep. The Public Charitable Hospitals (Temporary Provisions) Act, 1930 was the act that established the lottery; as this act expired in 1934, in accordance with its terms, the Public Hospitals Acts were the legislative basis for the scheme thereafter. The main organisers were Richard Duggan, Captain Spencer Freeman and Joe McGrath. Duggan was a well known Dublin bookmaker who had organised a number of sweepstakes in the decade prior to setting up the Hospitals' Sweepstake. Captain Freeman was a Welsh-born engineer and former captain in the British Army. After the Constitution of Ireland was enacted in 1937, the name Irish Hospitals' Sweepstake was adopted. The sweepstake was established because there was a need for investment in hospitals and medical services and the public finances were unable to meet this expense at the time. As the people of Ireland were unable to raise sufficient funds, because of the low population, a significant amount of the funds were raised in the United Kingdom and United States, often among the emigrant Irish. Potentially winning tickets were drawn from rotating drums, usually by nurses in uniform. Each such ticket was assigned to a horse expected to run in one of several horse races, including the Cambridgeshire Handicap, Derby and Grand National. Tickets that drew the favourite horses thus stood a higher likelihood of winning and a series of winning horses had to be chosen on the accumulator system, allowing for enormous prizes. The original sweepstake draws were held at The Mansion House, Dublin on 19 May 1939 under the supervision of the Chief Commissioner of Police, and were moved to the more permanent fixture at the Royal Dublin Society (RDS) in Ballsbridge later in 1940. The Adelaide Hospital in Dublin was the only hospital at the time not to accept money from the Hospitals Trust, as the governors disapproved of sweepstakes. From the 1960s onwards, revenues declined. The offices were moved to Lotamore House in Cork. Although giving the appearance of a public charitable lottery, with nurses featured prominently in the advertising and drawings, the Sweepstake was in fact a private for-profit lottery company, and the owners were paid substantial dividends from the profits. Fortune Magazine described it as "a private company run for profit and its handful of stockholders have used their earnings from the sweepstakes to build a group of industrial enterprises that loom quite large in the modest Irish economy. Waterford Glass, Irish Glass Bottle Company and many other new Irish companies were financed by money from this enterprise and up to 5,000 people were given jobs."[3] By his death in 1966, Joe McGrath had interests in the racing industry, and held the Renault dealership for Ireland besides large financial and property assets. He was known throughout Ireland for his tough business attitude but also by his generous spirit.At that time, Ireland was still one of the poorer countries in Europe; he believed in investment in Ireland. His home, Cabinteely House, was donated to the state in 1986. The house and the surrounding park are now in the ownership of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council who have invested in restoring and maintaining the house and grounds as a public park. In 1986, the Irish government created a new public lottery, and the company failed to secure the new contract to manage it. The final sweepstake was held in January 1986 and the company was unsuccessful for a licence bid for the Irish National Lottery, which was won by An Post later that year. The company went into voluntary liquidation in March 1987. The majority of workers did not have a pension scheme but the sweepstake had fed many families during lean times and was regarded as a safe job.The Public Hospitals (Amendment) Act, 1990 was enacted for the orderly winding up of the scheme which had by then almost £500,000 in unclaimed prizes and accrued interest. A collection of advertising material relating to the Irish Hospitals' Sweepstakes is among the Special Collections of National Irish Visual Arts Library. At the time of the Sweepstake's inception, lotteries were generally illegal in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. In the absence of other readily available lotteries, the Irish Sweeps became popular. Even though tickets were illegal outside Ireland, millions were sold in the US and Great Britain. How many of these tickets failed to make it back for the drawing is unknown. The United States Customs Service alone confiscated and destroyed several million counterfoils from shipments being returned to Ireland. In the UK, the sweepstakes caused some strain in Anglo-Irish relations, and the Betting and Lotteries Act 1934 was passed by the parliament of the UK to prevent export and import of lottery related materials. The United States Congress had outlawed the use of the US Postal Service for lottery purposes in 1890. A thriving black market sprang up for tickets in both jurisdictions. From the 1950s onwards, as the American, British and Canadian governments relaxed their attitudes towards this form of gambling, and went into the lottery business themselves, the Irish Sweeps, never legal in the United States,declined in popularity. Origins: Co Galway Dimensions :39cm x 31cm

Fine print advertising the 1950 Irish Hospital Sweepstake for the horserace ,the Irish Cambridgeshire Handicap. The Irish Hospital Sweepstake was a lottery established in the Irish Free State in 1930 as the Irish Free State Hospitals' Sweepstake to finance hospitals. It is generally referred to as the Irish Sweepstake, frequently abbreviated to Irish Sweeps or Irish Sweep. The Public Charitable Hospitals (Temporary Provisions) Act, 1930 was the act that established the lottery; as this act expired in 1934, in accordance with its terms, the Public Hospitals Acts were the legislative basis for the scheme thereafter. The main organisers were Richard Duggan, Captain Spencer Freeman and Joe McGrath. Duggan was a well known Dublin bookmaker who had organised a number of sweepstakes in the decade prior to setting up the Hospitals' Sweepstake. Captain Freeman was a Welsh-born engineer and former captain in the British Army. After the Constitution of Ireland was enacted in 1937, the name Irish Hospitals' Sweepstake was adopted. The sweepstake was established because there was a need for investment in hospitals and medical services and the public finances were unable to meet this expense at the time. As the people of Ireland were unable to raise sufficient funds, because of the low population, a significant amount of the funds were raised in the United Kingdom and United States, often among the emigrant Irish. Potentially winning tickets were drawn from rotating drums, usually by nurses in uniform. Each such ticket was assigned to a horse expected to run in one of several horse races, including the Cambridgeshire Handicap, Derby and Grand National. Tickets that drew the favourite horses thus stood a higher likelihood of winning and a series of winning horses had to be chosen on the accumulator system, allowing for enormous prizes. The original sweepstake draws were held at The Mansion House, Dublin on 19 May 1939 under the supervision of the Chief Commissioner of Police, and were moved to the more permanent fixture at the Royal Dublin Society (RDS) in Ballsbridge later in 1940. The Adelaide Hospital in Dublin was the only hospital at the time not to accept money from the Hospitals Trust, as the governors disapproved of sweepstakes. From the 1960s onwards, revenues declined. The offices were moved to Lotamore House in Cork. Although giving the appearance of a public charitable lottery, with nurses featured prominently in the advertising and drawings, the Sweepstake was in fact a private for-profit lottery company, and the owners were paid substantial dividends from the profits. Fortune Magazine described it as "a private company run for profit and its handful of stockholders have used their earnings from the sweepstakes to build a group of industrial enterprises that loom quite large in the modest Irish economy. Waterford Glass, Irish Glass Bottle Company and many other new Irish companies were financed by money from this enterprise and up to 5,000 people were given jobs."[3] By his death in 1966, Joe McGrath had interests in the racing industry, and held the Renault dealership for Ireland besides large financial and property assets. He was known throughout Ireland for his tough business attitude but also by his generous spirit.At that time, Ireland was still one of the poorer countries in Europe; he believed in investment in Ireland. His home, Cabinteely House, was donated to the state in 1986. The house and the surrounding park are now in the ownership of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council who have invested in restoring and maintaining the house and grounds as a public park. In 1986, the Irish government created a new public lottery, and the company failed to secure the new contract to manage it. The final sweepstake was held in January 1986 and the company was unsuccessful for a licence bid for the Irish National Lottery, which was won by An Post later that year. The company went into voluntary liquidation in March 1987. The majority of workers did not have a pension scheme but the sweepstake had fed many families during lean times and was regarded as a safe job.The Public Hospitals (Amendment) Act, 1990 was enacted for the orderly winding up of the scheme which had by then almost £500,000 in unclaimed prizes and accrued interest. A collection of advertising material relating to the Irish Hospitals' Sweepstakes is among the Special Collections of National Irish Visual Arts Library. At the time of the Sweepstake's inception, lotteries were generally illegal in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. In the absence of other readily available lotteries, the Irish Sweeps became popular. Even though tickets were illegal outside Ireland, millions were sold in the US and Great Britain. How many of these tickets failed to make it back for the drawing is unknown. The United States Customs Service alone confiscated and destroyed several million counterfoils from shipments being returned to Ireland. In the UK, the sweepstakes caused some strain in Anglo-Irish relations, and the Betting and Lotteries Act 1934 was passed by the parliament of the UK to prevent export and import of lottery related materials. The United States Congress had outlawed the use of the US Postal Service for lottery purposes in 1890. A thriving black market sprang up for tickets in both jurisdictions. From the 1950s onwards, as the American, British and Canadian governments relaxed their attitudes towards this form of gambling, and went into the lottery business themselves, the Irish Sweeps, never legal in the United States,declined in popularity. Origins: Co Galway Dimensions :39cm x 31cmThe Irish Hospitals Sweepstake was established because there was a need for investment in hospitals and medical services and the public finances were unable to meet this expense at the time. As the people of Ireland were unable to raise sufficient funds, because of the low population, a significant amount of the funds were raised in the United Kingdom and United States, often among the emigrant Irish. Potentially winning tickets were drawn from rotating drums, usually by nurses in uniform. Each such ticket was assigned to a horse expected to run in one of several horse races, including the Cambridgeshire Handicap, Derby and Grand National. Tickets that drew the favourite horses thus stood a higher likelihood of winning and a series of winning horses had to be chosen on the accumulator system, allowing for enormous prizes.

The original sweepstake draws were held at The Mansion House, Dublin on 19 May 1939 under the supervision of the Chief Commissioner of Police, and were moved to the more permanent fixture at the Royal Dublin Society (RDS) in Ballsbridge later in 1940. The Adelaide Hospital in Dublin was the only hospital at the time not to accept money from the Hospitals Trust, as the governors disapproved of sweepstakes. From the 1960s onwards, revenues declined. The offices were moved to Lotamore House in Cork. Although giving the appearance of a public charitable lottery, with nurses featured prominently in the advertising and drawings, the Sweepstake was in fact a private for-profit lottery company, and the owners were paid substantial dividends from the profits. Fortune Magazine described it as "a private company run for profit and its handful of stockholders have used their earnings from the sweepstakes to build a group of industrial enterprises that loom quite large in the modest Irish economy. Waterford Glass, Irish Glass Bottle Company and many other new Irish companies were financed by money from this enterprise and up to 5,000 people were given jobs."By his death in 1966, Joe McGrath had interests in the racing industry, and held the Renault dealership for Ireland besides large financial and property assets. He was known throughout Ireland for his tough business attitude but also by his generous spirit. At that time, Ireland was still one of the poorer countries in Europe; he believed in investment in Ireland. His home, Cabinteely House, was donated to the state in 1986. The house and the surrounding park are now in the ownership of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council who have invested in restoring and maintaining the house and grounds as a public park. In 1986, the Irish government created a new public lottery, and the company failed to secure the new contract to manage it. The final sweepstake was held in January 1986 and the company was unsuccessful for a licence bid for the Irish National Lottery, which was won by An Post later that year. The company went into voluntary liquidation in March 1987. The majority of workers did not have a pension scheme but the sweepstake had fed many families during lean times and was regarded as a safe job.The Public Hospitals (Amendment) Act, 1990 was enacted for the orderly winding up of the scheme,which had by then almost £500,000 in unclaimed prizes and accrued interest. A collection of advertising material relating to the Irish Hospitals' Sweepstakes is among the Special Collections of National Irish Visual Arts Library.In the United Kingdom and North America[edit]

At the time of the Sweepstake's inception, lotteries were generally illegal in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. In the absence of other readily available lotteries, the Irish Sweeps became popular. Even though tickets were illegal outside Ireland, millions were sold in the US and Great Britain. How many of these tickets failed to make it back for the drawing is unknown. The United States Customs Service alone confiscated and destroyed several million counterfoils from shipments being returned to Ireland. In the UK, the sweepstakes caused some strain in Anglo-Irish relations, and the Betting and Lotteries Act 1934 was passed by the parliament of the UK to prevent export and import of lottery related materials.[6][7] The United States Congress had outlawed the use of the US Postal Service for lottery purposes in 1890. A thriving black market sprang up for tickets in both jurisdictions. From the 1950s onwards, as the American, British and Canadian governments relaxed their attitudes towards this form of gambling, and went into the lottery business themselves, the Irish Sweeps, never legal in the United States,[8]:227 declined in popularity. -

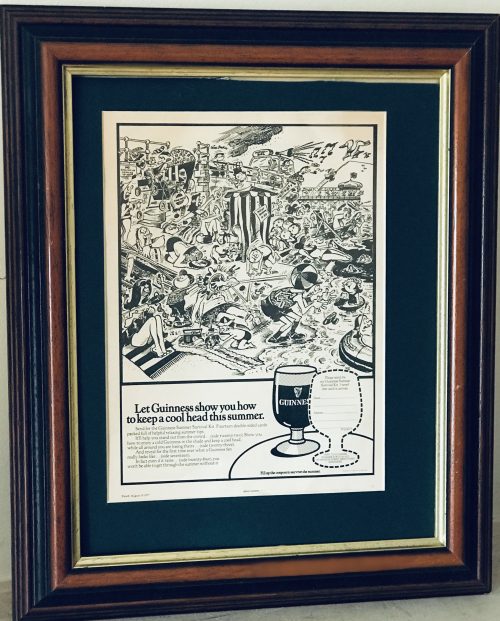

Cartoon Page from the satirical Punch Magazine August 10 1977 advertising a Guinness competition-Let Guinness show you how to keep a cool head this summer. Origins : UK Dimensions:44cm x 38cm Glazed Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.”

Cartoon Page from the satirical Punch Magazine August 10 1977 advertising a Guinness competition-Let Guinness show you how to keep a cool head this summer. Origins : UK Dimensions:44cm x 38cm Glazed Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” -

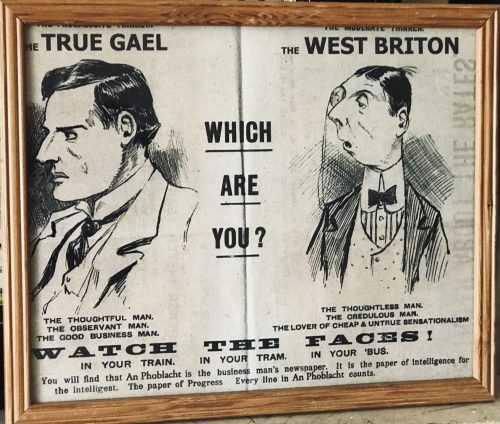

22cm x 28cm Quite hilarious now (but deadly serious at the time) political cartoon advertising the distinctions between a "True Gael" and a "West Briton",This was published in An Phoblacht in the 1930s,which was the media arm of Sinn Fein and its chief source of distributing propaganda. West Brit, an abbreviation of West Briton, is a derogatory term for an Irish person who is perceived as being anglophilic in matters of culture or politics.[1][2][3] West Britain is a description of Ireland emphasising it as under British influence.

22cm x 28cm Quite hilarious now (but deadly serious at the time) political cartoon advertising the distinctions between a "True Gael" and a "West Briton",This was published in An Phoblacht in the 1930s,which was the media arm of Sinn Fein and its chief source of distributing propaganda. West Brit, an abbreviation of West Briton, is a derogatory term for an Irish person who is perceived as being anglophilic in matters of culture or politics.[1][2][3] West Britain is a description of Ireland emphasising it as under British influence.History

"West Britain" was used with reference to the Acts of Union 1800 which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Similarly "North Britain" for Scotland used after the 1603 Union of the Crowns and the Acts of Union 1707 connected it to the Kingdom of England ("South Britain"). In 1800 Thomas Grady, a Limerick unionist, published a collection of light verse called The West Briton, while an anti-union cartoon depicted an official offering bribes and proclaiming "God save the King & his Majesty's subjects of west Britain that is to be!"In 1801 the Latin description of George III on the Great Seal of the Realm was changed from MAGNÆ BRITANNIÆ FRANCIÆ ET HIBERNIÆ REX "King of Great Britain, France and Ireland" to BRITANNIARUM REX "King of the Britains", dropping the claim to the French throne and describing Great Britain and Ireland as "the Britains". Irish unionist MP Thomas Spring Rice (later Lord Monteagle of Brandon) said on 23 April 1834 in the House of Commons in opposing Daniel O'Connell's motion for Repeal of the Union, "I should prefer the name of West Britain to that of Ireland".Rice was derided by Henry Grattan later in the same debate: "He tells us, that he belongs to England, and designates himself as a West Briton."Daniel O'Connell himself used the phrase at a pro-Repeal speech in Dublin in February 1836:The people of Ireland are ready to become a portion of the empire, provided they be made so in reality and not in name alone; they are ready to become a kind of West Britons, if made so in benefits and justice; but if not, we are Irishmen again.

Here, O'Connell was hoping that Ireland would soon become as prosperous as "North Britain" had become after 1707, but if the Union did not deliver this, then some form of Irish home rule was essential. The Dublin administration as conducted in the 1830s was, by implication, an unsatisfactory halfway house between these two ideals, and as a prosperous "West Britain" was unlikely, home rule was the rational best outcome for Ireland. "West Briton" next came to prominence in a pejorative sense during the land struggle of the 1880s. D. P. Moran, who founded The Leader in 1900, used the term frequently to describe those who he did not consider sufficiently Irish. It was synonymous with those he described as "Sourfaces", who had mourned the death of the Queen Victoria in 1901. It included virtually all Church of Ireland Protestants and those Catholics who did not measure up to his definition of "Irish Irelanders". In 1907, Canon R. S. Ross-Lewin published a collection of loyal Irish poems under the pseudonym "A County of Clare West Briton", explaining the epithet in the foreword:Now, what is the exact definition and up-to-date meaning of that term? The holder of the title may be descended from O'Connors and O'Donelans and ancient Irish Kings. He may have the greatest love for his native land, desirous to learn the Irish language, and under certain conditions to join the Gaelic League. He may be all this, and rejoice in the victory of an Irish horse in the "Grand National", or an Irish dog at "Waterloo", or an Irish tug-of-war team of R.I.C. giants at Glasgow or Liverpool, but, if he does not at the same time hate the mere Saxon, and revel in the oft resuscitated pictures of long past periods, and the horrors of the penal laws he is a mere "West Briton", his Irish blood, his Irish sympathies go for nothing. He misses the chief qualifications to the ranks of the "Irish best", if he remains an imperialist, and sees no prospect of peace or happiness or return of prosperity in the event of the Union being severed. In this sense, Lord Roberts, Lord Charles Beresford and hundreds of others, of whom all Irishmen ought to be proud, are "West Britons", and thousands who have done nothing for the empire, under the just laws of which they live, who, perhaps, are mere descendants of Cromwell's soldiers, and even of Saxon lineage, with very little Celtic blood in their veins, are of the "Irish best".

Ernest Augustus Boyd's 1924 collection Portraits: real and imaginary included "A West Briton", which gave a table of West-Briton responses to keywords:-

-

Word Response Sinn Féin Pro-German Irish Vulgar England Mother-country Green Red Nationality Disloyalty Patriotism O.B.E. Self-determination Czecho-Slovakia

-

Contemporary usage

"Brit" meaning "British person", attested in 1884, is pejorative in Irish usage, though used as a value-neutral colloquialism in Great Britain. During the Troubles, among nationalists "the Brits" specifically meant the British Army in Northern Ireland. "West Brit" is today used by Irish people, chiefly within Ireland, to criticise a variety of perceived faults of other Irish people:- "Revisionism" (compare historical revisionism and historical negationism):

- Criticism of historical Irish uprisings. (State policy is to praise the patriotism of rebels up to the revolutionary period, while condemning later physical force republicans as antidemocratic.)

- highlighting perceived benefits of British influence in Ireland

- downplaying British culpability for historical disasters or atrocities

- Antipathy to Irish rebel songs.

- Anglophilia: following British popular culture; admiration for the British royal family; support for the Republic of Ireland rejoining the Commonwealth of Nations; highlighting positive British influence in the world, past or present

- Cultural cringe: appearing embarrassed by or disdainful of aspects of Irish culture, such as the Irish language, Hiberno-English, Gaelic games, or Irish traditional music

- Partitionism: Opposition or indifference to a United Ireland; neo-unionism

I'm an effete, urban Irishman. I was an avid radio listener as a boy, but it was the BBC, not RTÉ. I was a West Brit from the start. ... I'm a kind of child of the Pale. ... I think I was born to succeed here [in the UK]; I have much more freedom than I had in Ireland.

Wogan became a dual citizen of Ireland and the UK, and was eventually knighted by Queen Elizabeth II.Similar terms

Castle Catholic was applied more specifically by Republicans to middle-class Catholics assimilated into the pro-British establishment, after Dublin Castle, the centre of the British administration. Sometimes the exaggerated pronunciation spelling Cawtholic was used to suggest an accent imitative of British Received Pronunciation. These identified Catholic unionists whose involvement in the British system was the whole aim of O'Connell's Emancipation Act of 1829. Having and exercising their new legal rights under the Act, Castle Catholics were then rather illogically being pilloried by other Catholics for exercising them to the full. The old-fashioned word shoneen (from Irish: Seoinín, diminutive of Seán, thus literally 'Little John', and apparently a reference to John Bull) was applied to those who emulated the homes, habits, lifestyle, pastimes, clothes, and zeitgeist of the Protestant Ascendancy. P. W. Joyce's English As We Speak It in Ireland defines it as "a gentleman in a small way: a would-be gentleman who puts on superior airs." A variant since c. 1840, jackeen ('Little Jack'), was used in the countryside in reference to Dubliners with British sympathies; it is a pun, substituting the nickname Jack for John, as a reference to the Union Jack, the British flag. In the 20th century, jackeen took on the more generalized meaning of "a self-assertive worthless fellow".Antonyms

The term is sometimes contrasted with Little Irelander, a derogatory term for an Irish person who is seen as excessively nationalistic, Anglophobic and xenophobic, sometimes also practising a strongly conservative form of Roman Catholicism. This term was popularised by Seán Ó Faoláin."Little Englander" had been an equivalent term in British politics since about 1859. An antonym of jackeen, in its modern sense of an urban (and strongly British-influenced) Dubliner, is culchie, referring to a stereotypical Irish person of the countryside (and rarely pro-British). -

-

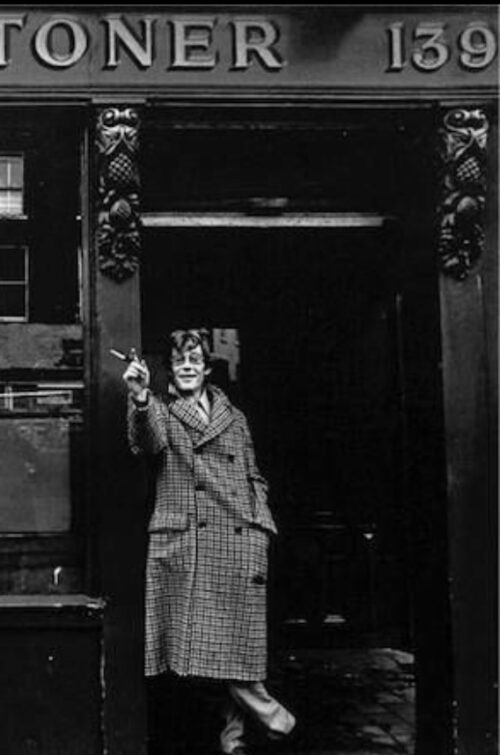

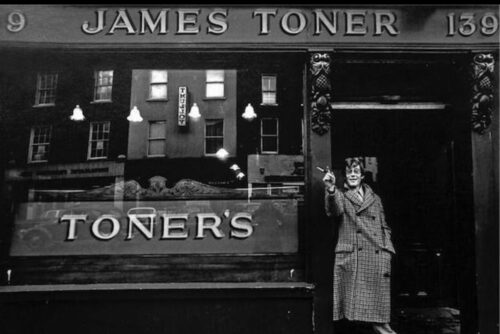

45cm x 35cm. Dublin Iconic b&w photograph of legendary Actor & Bon Viveur Peter O'Toole outside one of his favourite Dublin Watering Hole's-Toners of Baggott Street. Peter Seamus O'Toole ( 2 August 1932 – 14 December 2013) was a British stage and film actor of Irish descent. He attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and began working in the theatre, gaining recognition as a Shakespearean actor at the Bristol Old Vic and with the English Stage Company. In 1959 he made his West End debut in The Long and the Short and the Tall, and played the title role in Hamlet in the National Theatre’s first production in 1963. Excelling on the London stage, O'Toole was known as a "hellraiser" off it. Making his film debut in 1959, O'Toole achieved international recognition playing T. E. Lawrence in Lawrence of Arabia (1962) for which he received his first nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor. He was nominated for this award another seven times – for playing King Henry II in both Becket (1964) and The Lion in Winter (1968), Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1969), The Ruling Class (1972), The Stunt Man (1980), My Favorite Year (1982), and Venus (2006) – and holds the record for the most Academy Award nominations for acting without a win. In 2002, O'Toole was awarded the Academy Honorary Award for his career achievements. He was additionally the recipient of four Golden Globe Awards, one BAFTA Award for Best British Actor and one Primetime Emmy Award. Brought up in Leeds, England in a Yorkshire Irish family, O'Toole has appeared on lists of greatest actors from publications in England and Ireland. In 2020, he was listed at number 4 on The Irish Times list of Ireland's greatest film actors. Situated on Baggot Street, Toners is one of Dublin’s oldest and most famous traditional pubs. To prove this, we were the overall winners of “Best Traditional Pub” in the National Hospitality Awards 2014. In September 2015 we also won Dublin Bar of the Year at the Sky Bar of the Year Awards. Original features in the pub take visitors back in time, including the old stock drawers behind the bar from when Toners first opened in 1818 as a bar and grocery shop. The interior details like the glazed cabinets filled with curio, elaborate mirrors, the brass bar taps and flagstone floors to mention a few, makes you feel like you are stepping in to a museum… A museum in which you can drink in! Frequented by many of Ireland’s literary greats, including Patrick Kavanagh, the pub was also a favourite spot of W.B. Yeats and the snug is said to be the only place he would drink when he took an occasional tipple.

45cm x 35cm. Dublin Iconic b&w photograph of legendary Actor & Bon Viveur Peter O'Toole outside one of his favourite Dublin Watering Hole's-Toners of Baggott Street. Peter Seamus O'Toole ( 2 August 1932 – 14 December 2013) was a British stage and film actor of Irish descent. He attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and began working in the theatre, gaining recognition as a Shakespearean actor at the Bristol Old Vic and with the English Stage Company. In 1959 he made his West End debut in The Long and the Short and the Tall, and played the title role in Hamlet in the National Theatre’s first production in 1963. Excelling on the London stage, O'Toole was known as a "hellraiser" off it. Making his film debut in 1959, O'Toole achieved international recognition playing T. E. Lawrence in Lawrence of Arabia (1962) for which he received his first nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor. He was nominated for this award another seven times – for playing King Henry II in both Becket (1964) and The Lion in Winter (1968), Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1969), The Ruling Class (1972), The Stunt Man (1980), My Favorite Year (1982), and Venus (2006) – and holds the record for the most Academy Award nominations for acting without a win. In 2002, O'Toole was awarded the Academy Honorary Award for his career achievements. He was additionally the recipient of four Golden Globe Awards, one BAFTA Award for Best British Actor and one Primetime Emmy Award. Brought up in Leeds, England in a Yorkshire Irish family, O'Toole has appeared on lists of greatest actors from publications in England and Ireland. In 2020, he was listed at number 4 on The Irish Times list of Ireland's greatest film actors. Situated on Baggot Street, Toners is one of Dublin’s oldest and most famous traditional pubs. To prove this, we were the overall winners of “Best Traditional Pub” in the National Hospitality Awards 2014. In September 2015 we also won Dublin Bar of the Year at the Sky Bar of the Year Awards. Original features in the pub take visitors back in time, including the old stock drawers behind the bar from when Toners first opened in 1818 as a bar and grocery shop. The interior details like the glazed cabinets filled with curio, elaborate mirrors, the brass bar taps and flagstone floors to mention a few, makes you feel like you are stepping in to a museum… A museum in which you can drink in! Frequented by many of Ireland’s literary greats, including Patrick Kavanagh, the pub was also a favourite spot of W.B. Yeats and the snug is said to be the only place he would drink when he took an occasional tipple.History of Toners Pub

- Acquired first License by Andrew Rogers 1818 – 1859.

- William F. Drought 1859 – 1883, Grocer, Tea, Wine & Spirit Merchant

- John O’Neill 1883 – 1904, Tea, Wine & Spirit Merchant

- James M Grant 1904 – 1923, Grocer, Tea, Wine & Spirit Merchant

- James Toner 1923 – 1970, Grocer, Tea, Wine & Spirit Merchant

- Joe Colgan Solicitor 1970 – 1976

- Ned & Patricia Dunne & Partner Tom Murphy 1976 – 1987

- Frank & Michael Quinn 1987 – Present

Snug of the Year 2010

Toners won “Snug of the Year” 2010, a competition hosted by Powers Whiskey. 110 pubs across Ireland were shortlisted, and after counting the public’s votes Toners was announced the winner. A snug is a private area separated within a pub and is a timeless feature in a traditional Irish pub. Like the one in Toners, it typically has its own door, a rugged bench and is completely private. Back in the day it was where the likes of policemen, lovers and the Irish literati met up.

Toners won “Snug of the Year” 2010, a competition hosted by Powers Whiskey. 110 pubs across Ireland were shortlisted, and after counting the public’s votes Toners was announced the winner. A snug is a private area separated within a pub and is a timeless feature in a traditional Irish pub. Like the one in Toners, it typically has its own door, a rugged bench and is completely private. Back in the day it was where the likes of policemen, lovers and the Irish literati met up.

Toners Yard

Since Toners opened its doors to the yard in 2012 it has been a very popular spot with both locals and tourists. The beer garden is ideal for sunny days as it gets the sun from morning until evening, and if it is a bit chillier the heaters will keep you warm.Mumford & Sons – Arthurs Day 2012 in Toners Yard

Arthurs Day, the annual celebration of all things Guinness, has been hugely successful since it launched in 2009. Diageo launched a “vote for your local” competition for Arthurs Day 2012. The public got a chance to vote and help bring a headline artist to their local pub. Toners, serving the best pint of Guinness in Dublin, got so much support from everyone and ended up being one of the winning pubs. The winning pubs were kept a secret until the night of Arthurs Day and to everyone’s delight, Mumford & Sons walked in to Toners Yard and played an amazing set. -