-

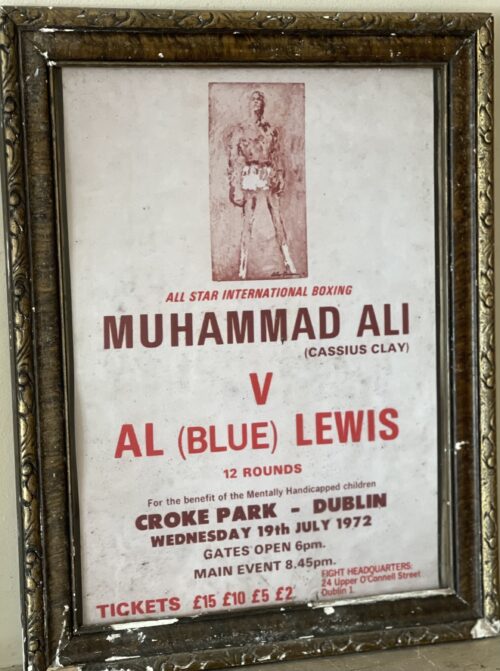

48cm x 39cm. Dublin July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.

48cm x 39cm. Dublin July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history. -

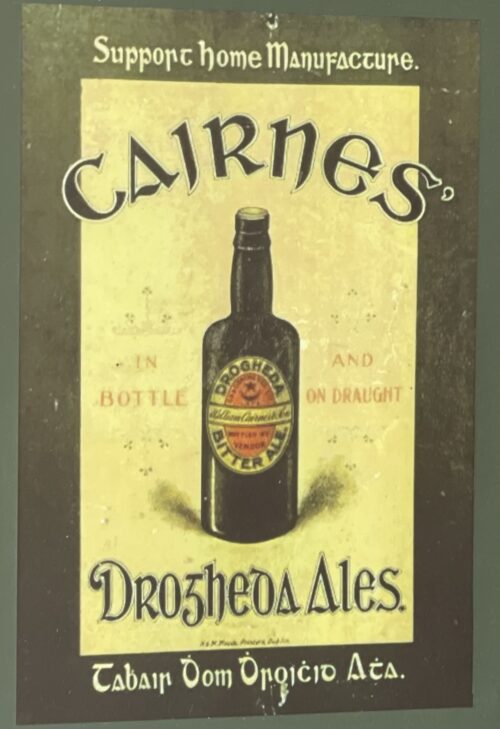

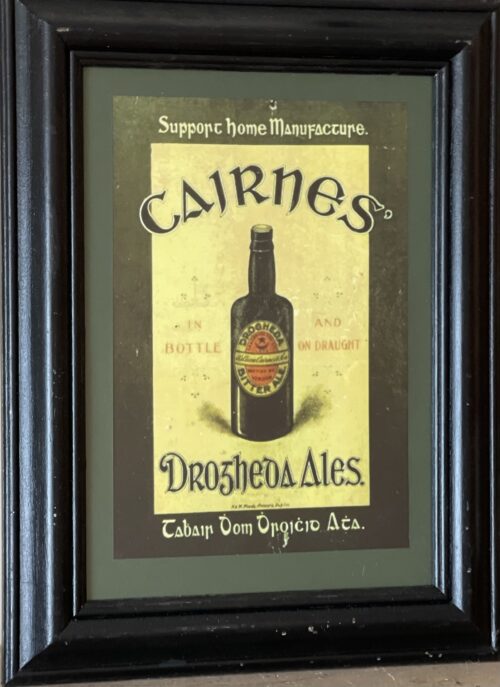

38cm x 30cm Drogheda Cairnes Ltd, Drogheda, Co Louth, Ireland. Founded 1828 by William Cairnes. Registered April 1890 as the Castlebellingham & Drogheda Breweries Ltd. to acquire John Woolsey & Co. Ltd, Castlebellingham and William Cairnes & Son. Name changed as above in November 1933. Acquired by Guinness and ceased brewing in October 1959. From the Brewery History Society Journal Number 91 Founded in 1828 by William Cairnes with good markets in both Dublin and Belfast. In 1850 they extended their malt liquor portfolio to include porter. The brewery was closed in 1959 as part of a rationalisation plan when the Cherry-Cairnes partnership was dissolved, to be subsequently replaced by the Irish Ale Breweries Group, (a Guinness/Allied Breweries combination). Irish Ale Breweries was formally dissolved in 1988, becoming Guinness Ireland.

38cm x 30cm Drogheda Cairnes Ltd, Drogheda, Co Louth, Ireland. Founded 1828 by William Cairnes. Registered April 1890 as the Castlebellingham & Drogheda Breweries Ltd. to acquire John Woolsey & Co. Ltd, Castlebellingham and William Cairnes & Son. Name changed as above in November 1933. Acquired by Guinness and ceased brewing in October 1959. From the Brewery History Society Journal Number 91 Founded in 1828 by William Cairnes with good markets in both Dublin and Belfast. In 1850 they extended their malt liquor portfolio to include porter. The brewery was closed in 1959 as part of a rationalisation plan when the Cherry-Cairnes partnership was dissolved, to be subsequently replaced by the Irish Ale Breweries Group, (a Guinness/Allied Breweries combination). Irish Ale Breweries was formally dissolved in 1988, becoming Guinness Ireland. -

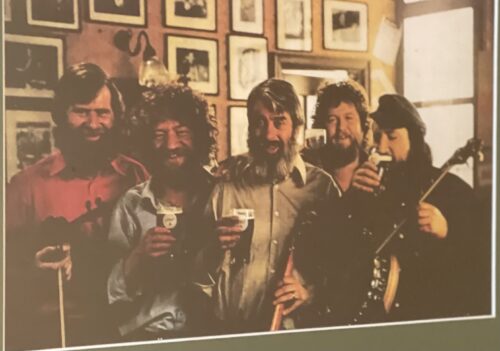

Fantastic framed .large Dubliners drinking pints of Bass display with autographs of all the band members underneath. 75cm x 66cm Dublin The Dubliners were quite simply one of the most famous Irish folk bands of all time.Founded in 1962,they enjoyed a 50 year career with the success of the band centred on their two lead singers,Luke Kelly and Ronnie Drew.They garnered massive international acclaim with their lively Irish folk songs,traditional street ballads and instrumentals eventually crossing over to mainstream culture by appearing on Top of the Pops in 1967 with "Seven Drunken Nights" which sold over 250000 singles in the UK alone.Later a number of collaborations with the Pogues saw them enter the UK singles charts again on another 2 occasions.Instrumental in popularising Irish folk music abroad ,they influenced many generations of Irish bands and covers of Irish ballads such as Raglan Road and the Auld Triangle by Luke Kelly and Ronnie Drew tend to be regarded as definitive versions.They also enjoyed a hard drinking and partying image and this advertising collaboration with Bass Ales must be seen as the perfect fit in terms of a target audience !

Fantastic framed .large Dubliners drinking pints of Bass display with autographs of all the band members underneath. 75cm x 66cm Dublin The Dubliners were quite simply one of the most famous Irish folk bands of all time.Founded in 1962,they enjoyed a 50 year career with the success of the band centred on their two lead singers,Luke Kelly and Ronnie Drew.They garnered massive international acclaim with their lively Irish folk songs,traditional street ballads and instrumentals eventually crossing over to mainstream culture by appearing on Top of the Pops in 1967 with "Seven Drunken Nights" which sold over 250000 singles in the UK alone.Later a number of collaborations with the Pogues saw them enter the UK singles charts again on another 2 occasions.Instrumental in popularising Irish folk music abroad ,they influenced many generations of Irish bands and covers of Irish ballads such as Raglan Road and the Auld Triangle by Luke Kelly and Ronnie Drew tend to be regarded as definitive versions.They also enjoyed a hard drinking and partying image and this advertising collaboration with Bass Ales must be seen as the perfect fit in terms of a target audience ! -

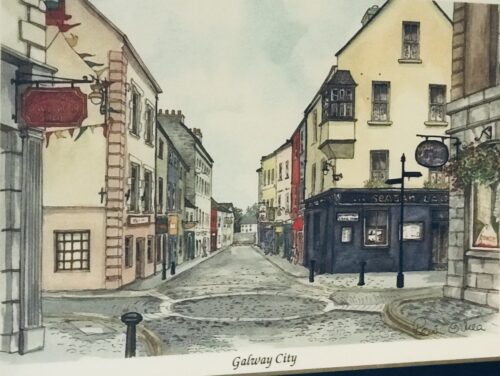

Beautiful depiction of Galway City. These beautiful quaint scenes from six individual towns were originally table and have been superbly mounted and framed to create a memorable souvenir collection.Originally painted by talented local artist Roisin O Shea,the prints depict everyday scenes of streetlife in Killarney,Kilkenny,Blarney,Galway,Kinsale and Youghal. Lahinch Co Clare 33cm x 39cm

Beautiful depiction of Galway City. These beautiful quaint scenes from six individual towns were originally table and have been superbly mounted and framed to create a memorable souvenir collection.Originally painted by talented local artist Roisin O Shea,the prints depict everyday scenes of streetlife in Killarney,Kilkenny,Blarney,Galway,Kinsale and Youghal. Lahinch Co Clare 33cm x 39cm -

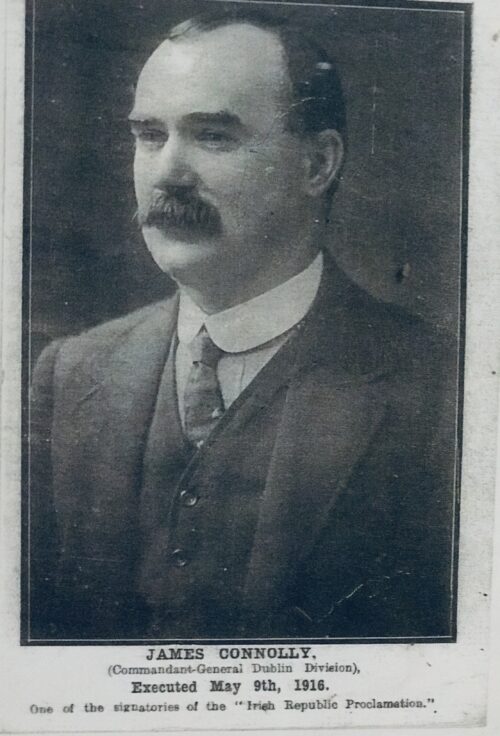

Beautiful and poignant collection of four of the 1916 Easter Rising Rebel Leaders who were executed by the British Crown Forces at Kilmainham Jail a few weeks later.Featured here are Padraig Pearse,Thomas Clarke,James Connolly,Thomas Kent. James Connolly (5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an Irish republican and socialist leader. Connolly was born in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, to Irish parents. He left school for working life at the age of 11. He also took a role in Scottish and American politics. He was a member of the Industrial Workers of the World and founder of the Irish Socialist Republican Party. With James Larkin, he was centrally involved in the Dublin lock-out of 1913, as a result of which the two men formed the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) that year. He opposed British rule in Ireland, and was one of the leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916. He was executed by firing squad following the Rising.

Beautiful and poignant collection of four of the 1916 Easter Rising Rebel Leaders who were executed by the British Crown Forces at Kilmainham Jail a few weeks later.Featured here are Padraig Pearse,Thomas Clarke,James Connolly,Thomas Kent. James Connolly (5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an Irish republican and socialist leader. Connolly was born in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, to Irish parents. He left school for working life at the age of 11. He also took a role in Scottish and American politics. He was a member of the Industrial Workers of the World and founder of the Irish Socialist Republican Party. With James Larkin, he was centrally involved in the Dublin lock-out of 1913, as a result of which the two men formed the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) that year. He opposed British rule in Ireland, and was one of the leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916. He was executed by firing squad following the Rising.Early life

Connolly was born in an Edinburgh slum in 1868, the third son of Irish parents John Connolly and Mary McGinn.His parents had moved to Scotland from County Monaghan, Ireland, and settled in the Cowgate, a ghetto where thousands of Irish people lived. He spoke with a Scottish accent throughout his life. He was born in St Patrick's Roman Catholic parish, in the Cowgate district of Edinburgh known as "Little Ireland". His father and grandfathers were labourers.He had an education up to the age of about ten in the local Catholic primary school. He left and worked in labouring jobs. Owing to the economic difficulties he was having, like his eldest brother John, he joined the British Army. He enlisted at age 14, falsifying his age and giving his name as Reid, as his brother John had done. He served in Ireland with the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Scots Regiment for nearly seven years, during a turbulent period in rural areas known as the Land War.He would later become involved in the land issue. He developed a deep hatred for the British Army that lasted his entire life.When he heard that his regiment was being transferred to India, he deserted. Connolly had another reason for not wanting to go to India; a young woman by the name of Lillie Reynolds. Lillie moved to Scotland with James after he left the army and they married in April 1890.They settled in Edinburgh. There, Connolly began to get involved in the Scottish Socialist Federation,[17] but with a young family to support, he needed a way to provide for them. He briefly established a cobbler's shop in 1895, but this failed after a few monthsas his shoe-mending skills were insufficient.He was strongly active with the socialist movement at the time, and prioritized this over his cobbling.Socialist involvement

In the 1880s, Connolly became influenced by Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx and would later advocate a type of socialism that was based in Marxist theory.[21] Connolly described himself as a socialist, while acknowledging the influence of Marx. He became secretary of the Scottish Socialist Federation. At the time his brother John was secretary; after John spoke at a rally in favour of the eight-hour day, however, he was fired from his job with the Edinburgh Corporation, so while he looked for work, James took over as secretary. During this time, Connolly became involved with the Independent Labour Party which Keir Hardie had formed in 1893. At some time during this period, he took up the study of, and advocated the use of, the neutral international language, Esperanto. His interest in Esperanto is implicit in his 1898 article "The Language Movement", which primarily attempts to promote socialism to the nationalist revolutionaries involved in the Gaelic Revival. By 1892 he was involved in the Scottish Socialist Federation, acting as its secretary from 1895. Two months after the birth of his third daughter, word came to Connolly that the Dublin Socialist Club was looking for a full-time secretary, a job that offered a salary of a pound a week. Connolly and his family moved to Dublin,where he took up the position. At his instigation, the club quickly evolved into the Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP).The ISRP is regarded by many Irish historians as a party of pivotal importance in the early history of Irish socialism and republicanism. While active as a socialist in Great Britain, Connolly was the founding editor of The Socialist newspaper and was among the founders of the Socialist Labour Partywhich split from the Social Democratic Federation in 1903. Connolly joined Maud Gonne and Arthur Griffith in the Dublin protests against the Boer War. A combination of frustration with the progress of the ISRP and economic necessity caused him to emigrate to the United States in September 1903, with no plans as to what he would do there.While in America he was a member of the Socialist Labor Party of America (1906), the Socialist Party of America (1909) and the Industrial Workers of the World, and founded the Irish Socialist Federation in New York, 1907. He famously had a chapter of his 1910 book Labour in Irish History entitled "A chapter of horrors: Daniel O’Connell and the working class." critical of the achiever of Catholic Emancipation 60 years earlier. On Connolly's return to Ireland in 1910 he was right-hand man to James Larkin in the Irish Transport and General Workers Union. He stood twice for the Wood Quay ward of Dublin Corporation but was unsuccessful. His name, and those of his family, appears in the 1911 Census of Ireland - his occupation is listed as "National Organiser Socialist Party".In 1913, in response to the Lockout, he, along with an ex-British officer, Jack White, founded the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), an armed and well-trained body of labour men whose aim was to defend workers and strikers, particularly from the frequent brutality of the Dublin Metropolitan Police. Though they only numbered about 250 at most, their goal soon became the establishment of an independent and socialist Irish nation. He also founded the Irish Labour Party as the political wing of the Irish Trades Union Congress in 1912 and was a member of its National Executive. Around this time he met Winifred Carney in Belfast, who became his secretary and would later accompany him during the Easter Rising. Like Vladimir Lenin, Connolly opposed the First World War explicitly from a socialist perspective. Rejecting the Redmondite position, he declared "I know of no foreign enemy of this country except the British Government."After Ireland is free, says the patriot who won't touch Socialism, we will protect all classes, and if you won't pay your rent you will be evicted same as now. But the evicting party, under command of the sheriff, will wear green uniforms and the Harp without the Crown, and the warrant turning you out on the roadside will be stamped with the arms of the Irish Republic.James Connolly, in Workers' Republic, 1899Easter Rising

Connolly and the ICA made plans for an armed uprising during the war, independently of the Irish Volunteers. In early 1916, believing the Volunteers were dithering, he attempted to goad them into action by threatening to send the ICA against the British Empire alone, if necessary. This alarmed the members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, who had already infiltrated the Volunteers and had plans for an insurrection that very year. In order to talk Connolly out of any such rash action, the IRB leaders, including Tom Clarke and Patrick Pearse, met with Connolly to see if an agreement could be reached. During the meeting, the IRB and the ICA agreed to act together at Easter of that year. During the Easter Rising, beginning on 24 April 1916, Connolly was Commandant of the Dublin Brigade. As the Dublin Brigade had the most substantial role in the rising, he was de factocommander-in-chief. Connolly's leadership in the Easter rising was considered formidable. Michael Collins said of Connolly that he "would have followed him through hell." Following the surrender, he said to other prisoners: "Don't worry. Those of us that signed the proclamation will be shot. But the rest of you will be set free."Death

Connolly was not actually held in gaol, but in a room (now called the "Connolly Room") at the State Apartments in Dublin Castle, which had been converted to a first-aid station for troops recovering from the war. Connolly was sentenced to death by firing squad for his part in the rising. On 12 May 1916 he was taken by military ambulance to Royal Hospital Kilmainham, across the road from Kilmainham Gaol, and from there taken to the gaol, where he was to be executed. While Connolly was still in hospital in Dublin Castle, during a visit from his wife and daughter, he said: "The Socialists will not understand why I am here; they forget I am an Irishman." Connolly had been so badly injured from the fighting (a doctor had already said he had no more than a day or two to live, but the execution order was still given) that he was unable to stand before the firing squad; he was carried to a prison courtyard on a stretcher. His absolution and last rites were administered by a Capuchin, Father Aloysius Travers. Asked to pray for the soldiers about to shoot him, he said: "I will say a prayer for all men who do their duty according to their lights."Instead of being marched to the same spot where the others had been executed, at the far end of the execution yard, he was tied to a chair and then shot. His body (along with those of the other leaders) was put in a mass grave without a coffin. The executions of the rebel leaders deeply angered the majority of the Irish population, most of whom had shown no support during the rebellion. It was Connolly's execution that caused the most controversy.Historians have pointed to the manner of execution of Connolly and similar rebels, along with their actions, as being factors that caused public awareness of their desires and goals and gathered support for the movements that they had died fighting for. The executions were not well received, even throughout Britain, and drew unwanted attention from the United States, which the British Government was seeking to bring into the war in Europe. H. H. Asquith, the Prime Minister, ordered that no more executions were to take place; an exception being that of Roger Casement, who was charged with high treasonand had not yet been tried. Location of Connolly's execution at Kilmainham Gaolin Dublin

Location of Connolly's execution at Kilmainham Gaolin DublinFamily

James Connolly and his wife Lillie had seven children. Nora became an influential writer and campaigner within the Irish-republican movement as an adult. Roddy continued his father's politics. In later years, both became members of the Oireachtas (Irish parliament). Moira became a doctor and married Richard Beech. One of Connolly's daughters Mona died in 1904 aged 13, when she burned herself while she did the washing for an aunt. Three months after James Connolly's execution his wife was received into the Catholic Church, at Church St. on 15 August.Legacy

Connolly's legacy in Ireland is mainly due to his contribution to the republican cause; his legacy as a socialist has been claimed by a variety of left-wing and left-republican groups, and he is also associated with the Labour Party which he founded. Connolly was among the few European members of the Second International who opposed, outright, World War I. This put him at odds with most of the socialist leaders of Europe. He was influenced by and heavily involved with the radical Industrial Workers of the World labour union, and envisaged socialism as Industrial Union control of production. Also he envisioned the IWW forming their own political party that would bring together the feuding socialist groups such as the Socialist Labor Party of America and the Socialist Party of America.Likewise, he envisaged independent Ireland as a socialist republic. His connection and views on Revolutionary Unionism and Syndicalism have raised debate on if his image for a workers republic would be one of State or Grassroots socialism.For a time he was involved with De Leonism and the Second International until he later broke with both. In Scotland, Connolly's thinking influenced socialists such as John Maclean, who would, like him, combine his leftist thinking with nationalist ideas when he formed the Scottish Workers Republican Party. The Connolly Association, a British organisation campaigning for Irish unity and independence, is named after Connolly. In 1928, Follonsby miners' lodge in the Durham coalfield unfurled a newly designed banner that included a portrait of Connolly on it. The banner was burned in 1938, replaced but then painted over in 1940. A reproduction of the 1938 Connolly banner was commissioned in 2011 by the Follonsby Miners’ Lodge Banner Association and it is regularly paraded at various events in County Durham ('Old King Coal' at Beamish Open Air museum, 'The Seven men of Jarrow' commemoration every June, the Durham Miners' Gala every second Saturday in July, the Tommy Hepburn annual memorial every October), in the wider UK and Ireland. There is a statue of James Connolly in Dublin, outside Liberty Hall, the offices of the SIPTU trade union. Another statue of Connolly stands in Union Park, Chicago near the offices of the UE union. There is a bust of Connolly in Troy, New York, in the park behind the statue of Uncle Sam. In March 2016 a statue of Connolly was unveiled by Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure minister Carál Ní Chuilín, and Connolly's great grandson, James Connolly Heron, on Falls Road in Belfast. In a 1972 interview on The Dick Cavett Show, John Lennon stated that James Connolly was an inspiration for his song, "Woman Is the Nigger of the World". Lennon quoted Connolly's 'the female is the slave of the slave' in explaining the feminist inspiration for the song. Connolly Station, one of the two main railway stations in Dublin, and Connolly Hospital, Blanchardstown, are named in his honour. In a 2002, BBC television production, 100 Greatest Britons where the British public were asked to register their vote, Connolly was voted in 64th place. In 1968, Irish group The Wolfe Tones released a single named "James Connolly", which reached number 15 in the Irish charts. The band Black 47 wrote and performed a song about Connolly that appears on their album Fire of Freedom. Irish singer-songwriter Niall Connolly has a song "May 12th, 1916 - A Song for James Connolly" on his album Dream Your Way Out of This One(2017). -

Atmospheric photograph of a moustached Michael Collins meeting the Kilkenny hurling team in advance of the 1921 Leinster hurling final, played at Croke Park on September 11, 1921. Dublin won the match on the score of Dublin 4-04 Kilkenny 1-05. 30cm x 40cm Durrow Co Laois Michael Collins was a revolutionary, soldier and politician who was a leading figure in the early-20th-century Irish struggle for independence. He was Chairman of the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State from January 1922 until his assassination in August 1922. Collins was born in Woodfield, County Cork, the youngest of eight children, and his family had republican connections reaching back to the 1798 rebellion. He moved to London in 1906, to become a clerk in the Post Office Savings Bank at Blythe House. He was a member of the London GAA, through which he became associated with the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Gaelic League. He returned to Ireland in 1916 and fought in the Easter Rising. He was subsequently imprisoned in the Frongoch internment camp as a prisoner of war, but was released in December 1916. Collins rose through the ranks of the Irish Volunteers and Sinn Féin after his release from Frongoch. He became a Teachta Dála for South Cork in 1918, and was appointed Minister for Finance in the First Dáil. He was present when the Dáil convened on 21 January 1919 and declared the independence of the Irish Republic. In the ensuing War of Independence, he was Director of Organisation and Adjutant General for the Irish Volunteers, and Director of Intelligence of the Irish Republican Army. He gained fame as a guerrilla warfare strategist, planning and directing many successful attacks on British forces, such as the assassination of key British intelligence agents in November 1920. After the July 1921 ceasefire, Collins and Arthur Griffith were sent to London by Éamon de Valera to negotiate peace terms. The resulting Anglo-Irish Treaty established the Irish Free State but depended on an Oath of Allegiance to the Crown, a condition that de Valera and other republican leaders could not reconcile with. Collins viewed the Treaty as offering "the freedom to achieve freedom", and persuaded a majority in the Dáil to ratify the Treaty. A provisional government was formed under his chairmanship in early 1922 but was soon disrupted by the Irish Civil War, in which Collins was commander-in-chief of the National Army. He was shot and killed in an ambush by anti-Treaty on 22nd August 1922.

Atmospheric photograph of a moustached Michael Collins meeting the Kilkenny hurling team in advance of the 1921 Leinster hurling final, played at Croke Park on September 11, 1921. Dublin won the match on the score of Dublin 4-04 Kilkenny 1-05. 30cm x 40cm Durrow Co Laois Michael Collins was a revolutionary, soldier and politician who was a leading figure in the early-20th-century Irish struggle for independence. He was Chairman of the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State from January 1922 until his assassination in August 1922. Collins was born in Woodfield, County Cork, the youngest of eight children, and his family had republican connections reaching back to the 1798 rebellion. He moved to London in 1906, to become a clerk in the Post Office Savings Bank at Blythe House. He was a member of the London GAA, through which he became associated with the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Gaelic League. He returned to Ireland in 1916 and fought in the Easter Rising. He was subsequently imprisoned in the Frongoch internment camp as a prisoner of war, but was released in December 1916. Collins rose through the ranks of the Irish Volunteers and Sinn Féin after his release from Frongoch. He became a Teachta Dála for South Cork in 1918, and was appointed Minister for Finance in the First Dáil. He was present when the Dáil convened on 21 January 1919 and declared the independence of the Irish Republic. In the ensuing War of Independence, he was Director of Organisation and Adjutant General for the Irish Volunteers, and Director of Intelligence of the Irish Republican Army. He gained fame as a guerrilla warfare strategist, planning and directing many successful attacks on British forces, such as the assassination of key British intelligence agents in November 1920. After the July 1921 ceasefire, Collins and Arthur Griffith were sent to London by Éamon de Valera to negotiate peace terms. The resulting Anglo-Irish Treaty established the Irish Free State but depended on an Oath of Allegiance to the Crown, a condition that de Valera and other republican leaders could not reconcile with. Collins viewed the Treaty as offering "the freedom to achieve freedom", and persuaded a majority in the Dáil to ratify the Treaty. A provisional government was formed under his chairmanship in early 1922 but was soon disrupted by the Irish Civil War, in which Collins was commander-in-chief of the National Army. He was shot and killed in an ambush by anti-Treaty on 22nd August 1922. -

Beautifully atmospheric Raymond Campbell still life print depicting a familiar scene of an Irish Bar shelf or kitchen dresser.You can almost reach out and touch the bottles of Powers & Jameson Whiskey plus assorted items such as an old hurling sliotar,a sea shell, postcards etc Origins :Bray Co Wicklow. Dimensions : 68cm x 55cm. Unglazed Raymond Campbell has long been known as one of the modern masters of still life oil paintings. Instantly recognisable, his artwork is often characterised by arrangements of dusty vintage wine bottles, glasses and selections of fruit and cheeses. What isn’t so known about Raymond is how he began his working life as a refuse collector and laying carpets. Indeed it was the former which allowed him to salvage many of the vintage bottles which he uses for his subject matter to this day. Born in 1956 in Surrey, Raymond Campbell is now considered by many as the United Kingdom’s pre-eminent still life artist. His works “Second Home”, “The Gamble” and “The Lost Shoe” are among pieces which have been exhibited at The Summer Exhibition at The Royal Academy, London. He has had many sell-out one man exhibitions and has also exhibited several times at The Mall Galleries, London and numerous other galleries worldwide. His work can be found in many international private collections, particularly in the USA, Australia and across Europe.

Beautifully atmospheric Raymond Campbell still life print depicting a familiar scene of an Irish Bar shelf or kitchen dresser.You can almost reach out and touch the bottles of Powers & Jameson Whiskey plus assorted items such as an old hurling sliotar,a sea shell, postcards etc Origins :Bray Co Wicklow. Dimensions : 68cm x 55cm. Unglazed Raymond Campbell has long been known as one of the modern masters of still life oil paintings. Instantly recognisable, his artwork is often characterised by arrangements of dusty vintage wine bottles, glasses and selections of fruit and cheeses. What isn’t so known about Raymond is how he began his working life as a refuse collector and laying carpets. Indeed it was the former which allowed him to salvage many of the vintage bottles which he uses for his subject matter to this day. Born in 1956 in Surrey, Raymond Campbell is now considered by many as the United Kingdom’s pre-eminent still life artist. His works “Second Home”, “The Gamble” and “The Lost Shoe” are among pieces which have been exhibited at The Summer Exhibition at The Royal Academy, London. He has had many sell-out one man exhibitions and has also exhibited several times at The Mall Galleries, London and numerous other galleries worldwide. His work can be found in many international private collections, particularly in the USA, Australia and across Europe. -

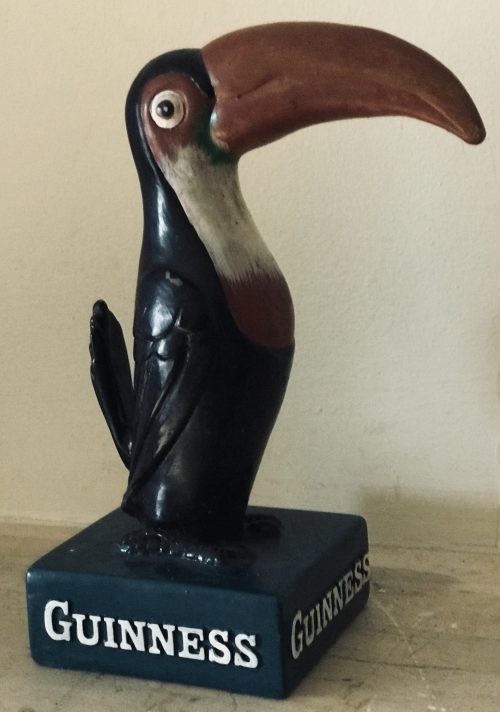

Original Resin Guinness Toucan (manufactured by Shannon) Dimensions :20cm x 10cm x 8cm 0.5kg For nearly two centuries of existence, the Guinness brewery had almost no need to formally advertise, allowing word-of-mouth to sell the beer, and sell it did. By the late 19th century, Guinness was one of the top three breweries between Britain and Ireland. In 1862, the company adopted an Irish harp as their logo and trademarked it in 1875. However, by the late 1920s, sales were declining, and in 1929, Rupert Guinness, then chair of the company, ran the first-ever Guinness print ad with the slogan “Guinness is good for you.” The very next year, the brewery hired advertising firm S.H. Benson. It was then, in 1930, that the story of the Guinness toucan began. The man responsible for the iconic bird and his animal companions is the English illustrator and draftsman John Gilroy. He was born in 1898 in Newcastle upon Tyne into a family of eight children, and his father, William, was a landscape painter. From a young age, Gilroy began copying the drawings in magazines, and it was quickly evident he would follow in his father’s professional footsteps. By 15, he was a cartoonist for the local newspaper. He won a scholarship to art school, and although World War I interrupted his studies, he entered London’s Royal College of Art in 1919. While he was still a student, he received his first commission for commercial art—a promotional pamphlet for the Hydraulic Engineering Co. Not long after graduating, Gilroy began working for S.H. Benson, where he would eventually work on Guiness.His first work with the firm was on campaigns for Skipper Sardines and Virol (a brand of malt extract). In his early years at Benson, he and his colleagues created clever characters to make their designs memorable: Baron de Beef, Signor Spaghetti, Miss Di Gester. All these playful characters likely primed Gilroy for the fun and whimsical designs he would eventually draw for Guinness in his 35 years working with the company. In the early 1930s S.H. Benson boasted an impressive staff of creatives beyond John Gilroy; the late Dorothy Sayers, now famous as a crime writer and poet, wrote copy for the agency. When Guinness approached the firm, they had an interesting request: the final advertising campaign should not be too much to do with beer, despite the fact that it was advertising—well—beer. They thought it would be vulgar. Instead, they preferred something that appealed to families and that highlighted the purported health benefits of the brew. They asked Gilroy to draft an ad showing a family drinking Guinness, but no one could seem to agree on what the family should look like, nor how they should be presented. Luckily, it was precisely family that led Gilroy to the particular idea that eventually spawned Guinness’s most famous ad campaigns. The artist had recently taken his son to the circus, recounts Guinness archive manager Fergus Brady, and had watched a sea lion balancing a ball on its nose. He realized how fun it would be to draw a sea lion balancing a pint of Guinness on its nose, and pitched the idea to Guinness. From there the series expanded to an entire menagerie. Gilroy drew ostriches, bears, pelicans, kangaroos, and of course, the toucan. Paired with Sayers’s inventive copy, the ads took off. In her most clever ad, she plays on the toucan / two-can homophone and on the idea that drinking Guinness offers a range of health benefits: “If he can say as you can / Guinness is good for you / How grand to be a Toucan — / Just think what Toucan do.” The illustration features a smiling toucan perched next to two shining pint glasses full of Guinness stout.

Original Resin Guinness Toucan (manufactured by Shannon) Dimensions :20cm x 10cm x 8cm 0.5kg For nearly two centuries of existence, the Guinness brewery had almost no need to formally advertise, allowing word-of-mouth to sell the beer, and sell it did. By the late 19th century, Guinness was one of the top three breweries between Britain and Ireland. In 1862, the company adopted an Irish harp as their logo and trademarked it in 1875. However, by the late 1920s, sales were declining, and in 1929, Rupert Guinness, then chair of the company, ran the first-ever Guinness print ad with the slogan “Guinness is good for you.” The very next year, the brewery hired advertising firm S.H. Benson. It was then, in 1930, that the story of the Guinness toucan began. The man responsible for the iconic bird and his animal companions is the English illustrator and draftsman John Gilroy. He was born in 1898 in Newcastle upon Tyne into a family of eight children, and his father, William, was a landscape painter. From a young age, Gilroy began copying the drawings in magazines, and it was quickly evident he would follow in his father’s professional footsteps. By 15, he was a cartoonist for the local newspaper. He won a scholarship to art school, and although World War I interrupted his studies, he entered London’s Royal College of Art in 1919. While he was still a student, he received his first commission for commercial art—a promotional pamphlet for the Hydraulic Engineering Co. Not long after graduating, Gilroy began working for S.H. Benson, where he would eventually work on Guiness.His first work with the firm was on campaigns for Skipper Sardines and Virol (a brand of malt extract). In his early years at Benson, he and his colleagues created clever characters to make their designs memorable: Baron de Beef, Signor Spaghetti, Miss Di Gester. All these playful characters likely primed Gilroy for the fun and whimsical designs he would eventually draw for Guinness in his 35 years working with the company. In the early 1930s S.H. Benson boasted an impressive staff of creatives beyond John Gilroy; the late Dorothy Sayers, now famous as a crime writer and poet, wrote copy for the agency. When Guinness approached the firm, they had an interesting request: the final advertising campaign should not be too much to do with beer, despite the fact that it was advertising—well—beer. They thought it would be vulgar. Instead, they preferred something that appealed to families and that highlighted the purported health benefits of the brew. They asked Gilroy to draft an ad showing a family drinking Guinness, but no one could seem to agree on what the family should look like, nor how they should be presented. Luckily, it was precisely family that led Gilroy to the particular idea that eventually spawned Guinness’s most famous ad campaigns. The artist had recently taken his son to the circus, recounts Guinness archive manager Fergus Brady, and had watched a sea lion balancing a ball on its nose. He realized how fun it would be to draw a sea lion balancing a pint of Guinness on its nose, and pitched the idea to Guinness. From there the series expanded to an entire menagerie. Gilroy drew ostriches, bears, pelicans, kangaroos, and of course, the toucan. Paired with Sayers’s inventive copy, the ads took off. In her most clever ad, she plays on the toucan / two-can homophone and on the idea that drinking Guinness offers a range of health benefits: “If he can say as you can / Guinness is good for you / How grand to be a Toucan — / Just think what Toucan do.” The illustration features a smiling toucan perched next to two shining pint glasses full of Guinness stout.

John Gilroy, illustrator of some of Guinness’s most well-known advertisements. (Northeast History Tour)

Gilroy even created toucan ads specifically for the American market with the birds flying over landmarks like the Statue of Liberty, Mount Rushmore, and the Golden Gate Bridge—always carrying two pints on their beaks. Sadly, Guinness never approved and ran the ads. Over the years, Gilroy created nearly 100 advertisements and 50 poster designs for Guinness. Though he left S.H. Benson as an in-house artist in the 1940s, he continued to freelance for them and continued to create the beloved Guinness zoo ads, crafting new scenarios for his Guinness-loving animals and their beleaguered zookeeper. Other vintage Guinness ads from the time feature simpler jingles and catchphrases. “My goodness—my Guinness” often features an animal stealing a man’s pint in comical fashions—an ostrich swallows it, a kangaroo hides the bottle in its pouch, a crocodile holds the pint between his massive jaws, and so on. In another, a smirking tortoise carries a pint on its back under the text, “Have a Guinness when you’re tired.” A man pulls a cart while his horse relaxes and goes for a ride—“Guinness for strength.” There is a playfulness to all of them. Even the ad in which a man is being chased by a lion feels funny—of course, the lion is chasing the man not to eat him, but to steal his beer. The lion is smiling, his tongue lolling out of his mouth as he runs, and we’re in on the joke: he’ll get the Guinness in the end, and the man is panicking not to save his skin, but to save his beer.

With John Gilroy’s illustrations and Dorothy Sayers’s copy, the Guinness toucan ads were an immediate hit. (Guinness)

The ads ran primarily in the U.K. and in the 1930s and 1940s were immensely popular—likely the cheerful, cheeky animals and bright colors provided a small antidote to the horrors going on in Europe at the time. In 1939, all troops in the British Expeditionary Force in France received a bottle of Guinness with their Christmas dinner. The company remained committed to adding a touch of whimsy to their generally solid and forward-thinking business practices. To celebrate Guinness’s bicentennial in 1959, the company dropped 150,000 embossed bottles containing Guinness-related information and paraphernalia into the Atlantic Ocean. It is the same year, as well, that Guinness employed scientists to create the Guinness Draft we know today by pairing nitrogen gas and carbon dioxide—it is that combination that gives the beer its prized silky texture. In in 1963 and 1965, Guinness opened breweries in Nigeria and Malaysia, respectively, cementing the company’s global reach and impact. As the company modernized, so too did their advertising strategies. In 1982, the Guinness brewery switched ad firms and stopped running the zoo-themed ads—the toucan and its friends were no longer considered effective advertising techniques. However, nostalgia for the Guinness toucan remained, and the company has released limited-edition cans and merchandise featuring the original Gilroy drawings. In 2017, the 200th anniversary of Guinness in America, they released a number of decorative itemsimprinted with the image of the two-pint-touting toucans flying over Mount Rushmore. The image of Gilroy’s toucan still immediately brings Guinness to mind, and it remains an immensely memorable mascot of the world’s premier dark beer. Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.

Guinness coasters featuring the menagerie of John Gilroy’s advertisements. (Guinness)

The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm -

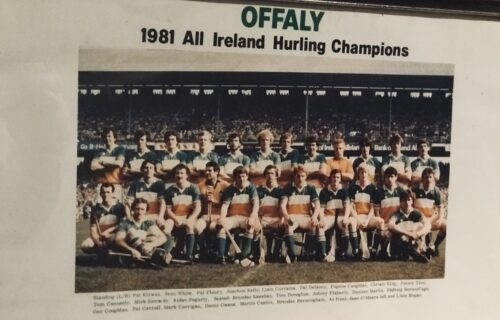

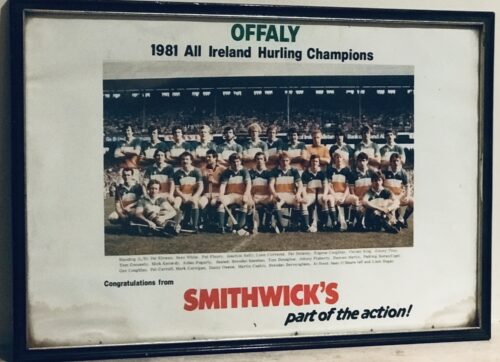

Superb Smithwicks sponsored team photograph of the 1981 All Ireland Hurling Champions -Offaly.The authenticity of this print and its worn appearance makes for an excellent addition to any GAA wall collection. 32cm x 47cm. Birr Co Offaly The 1981 All Ireland Hurling Final was the 94th All-Ireland Final and the culmination of the 1981 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship, an inter-county hurling tournament for the top teams in Ireland. The match was held at Croke Park, Dublin, on 6 September 1981, between Galway and Offaly. The reigning champions lost to their Leinster opponents, who won their first ever senior hurling title, on a score line of 2-12 to 0-15. Johnny Flaherty scored a handpassed goal in this game; this was before the handpassed goal was ruled out of the game as hurling's technical standards improved.

Superb Smithwicks sponsored team photograph of the 1981 All Ireland Hurling Champions -Offaly.The authenticity of this print and its worn appearance makes for an excellent addition to any GAA wall collection. 32cm x 47cm. Birr Co Offaly The 1981 All Ireland Hurling Final was the 94th All-Ireland Final and the culmination of the 1981 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship, an inter-county hurling tournament for the top teams in Ireland. The match was held at Croke Park, Dublin, on 6 September 1981, between Galway and Offaly. The reigning champions lost to their Leinster opponents, who won their first ever senior hurling title, on a score line of 2-12 to 0-15. Johnny Flaherty scored a handpassed goal in this game; this was before the handpassed goal was ruled out of the game as hurling's technical standards improved. -

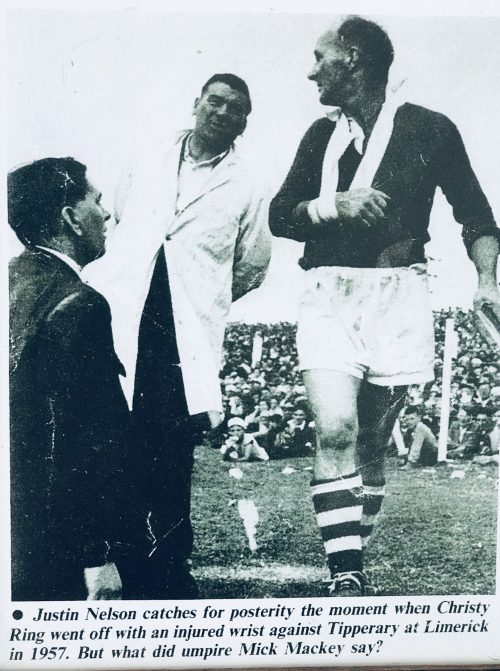

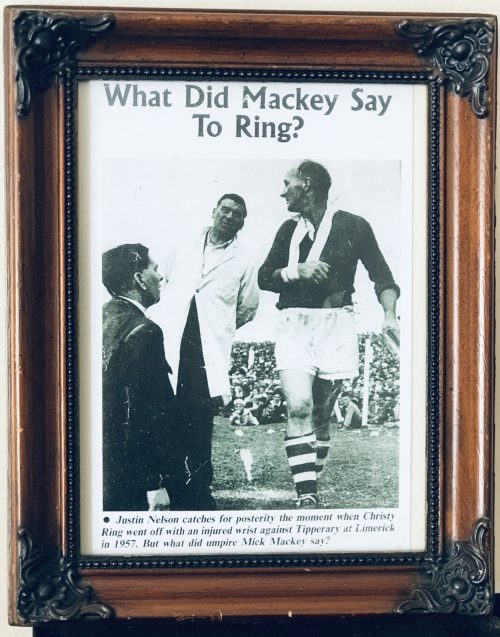

25cm x 20cm Abbeyfeale Co Limerick Nice souvenir of the iconic photograph taken by Justin Nelson.The following explanation of the actual verbal exchange between the two legends comes from Michael Moynihan of the Examiner newspaper. "When Christy Ring left the field of play injured in the 1957 Munster championship game between Cork and Waterford at Limerick, he strolled behind the goal, where he passed Mick Mackey, who was acting as umpire for the game. The two exchanged a few words as Ring made his way to the dressing-room.It was an encounter that would have been long forgotten if not for the photograph snapped at precisely the moment the two men met. The picture freezes the moment forever: Mackey, though long retired, still vigorous, still dark haired, somehow incongruous in his umpire’s white coat, clearly hopping a ball; Ring at his fighting weight, his right wrist strapped, caught in the typical pose of a man fielding a remark coming over his shoulder and returning it with interest. Two hurling eras intersect in the two men’s encounter: Limerick’s glory of the 30s, and Ring’s dominance of two subsequent decades.But nobody recorded what was said, and the mystery has echoed down the decades.But Dan Barrett has the answer.He forged a friendship with Ring from the usual raw materials. They had girls the same age, they both worked for oil companies, they didn’t live that far away from each other. And they had hurling in common.We often chatted away at home about hurling,” says Barrett. “In general he wouldn’t criticise players, although he did say about one player for Cork, ‘if you put a whistle on the ball he might hear it’.” Barrett saw Ring’s awareness of his whereabouts at first hand; even in the heat of a game he was conscious of every factor in his surroundings. “We went up to see him one time in Thurles,” says Barrett. “Don’t forget, people would come from all over the country to see a game just for Ring, and the place was packed to the rafters – all along the sideline people were spilling in on the field. “He came out to take a sideline cut at one stage and we were all roaring at him – ‘Go on Ring’, the usual – and he looked up into the crowd, the blue eyes, and he looked right at me. “The following day in work he called in and we were having a chat, and I said ‘if you caught that sideline yesterday, you’d have driven it up to the Devil’s Bit.’ “There was another chap there who said about me, ‘With all his talk he probably wasn’t there at all’. ‘He was there alright,’ said Ring. ‘He was over in the corner of the stand’. He picked me out in the crowd.” “He told me there was no way he’d come on the team as a sub. I remember then when Cork beat Tipperary in the Munster championship for the first time in a long time, there was a helicopter landed near the ground, the Cork crowd were saying ‘here’s Ring’ to rise the Tipp crowd. “I saw his last goal, for the Glen against Blackrock. He collided with a Blackrock man and he took his shot, it wasn’t a hard one, but the keeper put his hurley down and it hopped over his stick.” There were tough days against Tipperary – Ring took off his shirt one Monday to show his friends the bruising across his back from one Tipp defender who had a special knack of letting the Corkman out ahead in order to punish him with his stick. But Ring added that when a disagreement at a Railway Cup game with Leinster became physical, all of Tipperary piled in to back him up. One evening the talk turned to the photograph. Barrett packed the audience – “I had my wife there as a witness,” – and asked Ring the burning question: what had Mackey said to him? “’You didn’t get half enough of it’, said Mackey. ‘I’d expect nothing different from you,’ said Ring. “That was what was said.” You might argue – with some credibility – that learning what was said by the two men removes some of the force of the photograph; that if you remained in ignorance you’d be free to project your own hypothetical dialogue on the freeze-frame meeting of the two men. But nothing trumps actuality. The exchange carries a double authenticity: the pungency of slagging from one corner and the weariness of riposte from the other. Dan Barrett just wanted to set the record straight. “I’d heard people say ‘it will never be known’ and so on,” he says.“I thought it was no harm to let people know.” No harm at all" Origins ; Co Limerick Dimensions : 31cm x 25cm 1kgBorn in Castleconnell, County Limerick,Mick Mackey first arrived on the inter-county scene at the age of seventeen when he first linked up with the Limerick minor team, before later lining out with the junior side. He made his senior debut in the 1930–31 National League. Mackey went on to play a key part for Limerick during a golden age for the team, and won three All-Ireland medals, five Munster medals and five National Hurling League medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on two occasions, Mackey also captained the team to two All-Ireland victories. His brother, John Mackey, also shared in these victories while his father, "Tyler" Mackey was a one-time All-Ireland runner-up with Limerick. Mackey represented the Munster inter-provincial team for twelve years, winning eight Railway Cup medals during that period. At club level he won fifteen championship medals with Ahane. Throughout his inter-county career, Mackey made 42 championship appearances for Limerick. His retirement came following the conclusion of the 1947 championship. In retirement from playing, Mackey became involved in team management and coaching. As trainer of the Limerick senior team in 1955, he guided them to Munster victory. He also served as a selector on various occasions with both Limerick and Munster. Mackey also served as a referee. Mackey is widely regarded as one of the greatest hurlers in the history of the game. He was the inaugural recipient of the All-Time All-Star Award. He has been repeatedly voted onto teams made up of the sport's greats, including at centre-forward on the Hurling Team of the Centuryin 1984 and the Hurling Team of the Millennium in 2000. Origins : Co Limerick Dimensions : 28cm x 37cm 1kg

25cm x 20cm Abbeyfeale Co Limerick Nice souvenir of the iconic photograph taken by Justin Nelson.The following explanation of the actual verbal exchange between the two legends comes from Michael Moynihan of the Examiner newspaper. "When Christy Ring left the field of play injured in the 1957 Munster championship game between Cork and Waterford at Limerick, he strolled behind the goal, where he passed Mick Mackey, who was acting as umpire for the game. The two exchanged a few words as Ring made his way to the dressing-room.It was an encounter that would have been long forgotten if not for the photograph snapped at precisely the moment the two men met. The picture freezes the moment forever: Mackey, though long retired, still vigorous, still dark haired, somehow incongruous in his umpire’s white coat, clearly hopping a ball; Ring at his fighting weight, his right wrist strapped, caught in the typical pose of a man fielding a remark coming over his shoulder and returning it with interest. Two hurling eras intersect in the two men’s encounter: Limerick’s glory of the 30s, and Ring’s dominance of two subsequent decades.But nobody recorded what was said, and the mystery has echoed down the decades.But Dan Barrett has the answer.He forged a friendship with Ring from the usual raw materials. They had girls the same age, they both worked for oil companies, they didn’t live that far away from each other. And they had hurling in common.We often chatted away at home about hurling,” says Barrett. “In general he wouldn’t criticise players, although he did say about one player for Cork, ‘if you put a whistle on the ball he might hear it’.” Barrett saw Ring’s awareness of his whereabouts at first hand; even in the heat of a game he was conscious of every factor in his surroundings. “We went up to see him one time in Thurles,” says Barrett. “Don’t forget, people would come from all over the country to see a game just for Ring, and the place was packed to the rafters – all along the sideline people were spilling in on the field. “He came out to take a sideline cut at one stage and we were all roaring at him – ‘Go on Ring’, the usual – and he looked up into the crowd, the blue eyes, and he looked right at me. “The following day in work he called in and we were having a chat, and I said ‘if you caught that sideline yesterday, you’d have driven it up to the Devil’s Bit.’ “There was another chap there who said about me, ‘With all his talk he probably wasn’t there at all’. ‘He was there alright,’ said Ring. ‘He was over in the corner of the stand’. He picked me out in the crowd.” “He told me there was no way he’d come on the team as a sub. I remember then when Cork beat Tipperary in the Munster championship for the first time in a long time, there was a helicopter landed near the ground, the Cork crowd were saying ‘here’s Ring’ to rise the Tipp crowd. “I saw his last goal, for the Glen against Blackrock. He collided with a Blackrock man and he took his shot, it wasn’t a hard one, but the keeper put his hurley down and it hopped over his stick.” There were tough days against Tipperary – Ring took off his shirt one Monday to show his friends the bruising across his back from one Tipp defender who had a special knack of letting the Corkman out ahead in order to punish him with his stick. But Ring added that when a disagreement at a Railway Cup game with Leinster became physical, all of Tipperary piled in to back him up. One evening the talk turned to the photograph. Barrett packed the audience – “I had my wife there as a witness,” – and asked Ring the burning question: what had Mackey said to him? “’You didn’t get half enough of it’, said Mackey. ‘I’d expect nothing different from you,’ said Ring. “That was what was said.” You might argue – with some credibility – that learning what was said by the two men removes some of the force of the photograph; that if you remained in ignorance you’d be free to project your own hypothetical dialogue on the freeze-frame meeting of the two men. But nothing trumps actuality. The exchange carries a double authenticity: the pungency of slagging from one corner and the weariness of riposte from the other. Dan Barrett just wanted to set the record straight. “I’d heard people say ‘it will never be known’ and so on,” he says.“I thought it was no harm to let people know.” No harm at all" Origins ; Co Limerick Dimensions : 31cm x 25cm 1kgBorn in Castleconnell, County Limerick,Mick Mackey first arrived on the inter-county scene at the age of seventeen when he first linked up with the Limerick minor team, before later lining out with the junior side. He made his senior debut in the 1930–31 National League. Mackey went on to play a key part for Limerick during a golden age for the team, and won three All-Ireland medals, five Munster medals and five National Hurling League medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on two occasions, Mackey also captained the team to two All-Ireland victories. His brother, John Mackey, also shared in these victories while his father, "Tyler" Mackey was a one-time All-Ireland runner-up with Limerick. Mackey represented the Munster inter-provincial team for twelve years, winning eight Railway Cup medals during that period. At club level he won fifteen championship medals with Ahane. Throughout his inter-county career, Mackey made 42 championship appearances for Limerick. His retirement came following the conclusion of the 1947 championship. In retirement from playing, Mackey became involved in team management and coaching. As trainer of the Limerick senior team in 1955, he guided them to Munster victory. He also served as a selector on various occasions with both Limerick and Munster. Mackey also served as a referee. Mackey is widely regarded as one of the greatest hurlers in the history of the game. He was the inaugural recipient of the All-Time All-Star Award. He has been repeatedly voted onto teams made up of the sport's greats, including at centre-forward on the Hurling Team of the Centuryin 1984 and the Hurling Team of the Millennium in 2000. Origins : Co Limerick Dimensions : 28cm x 37cm 1kg -

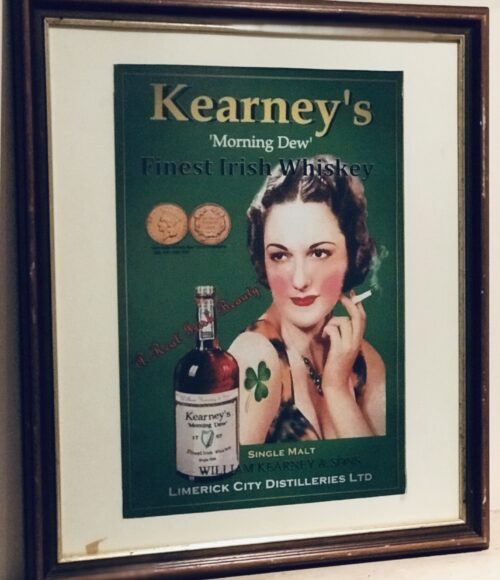

Charming 1940s advert from the merchant bottler Wm Kearney & Sons Limerick City.These bottling merchants would bottle for the major brands such as Jamesons and Bushmills and very often would distill their own single malt whiskey as well, usually for the local market.The "real Irish beauty " featured smoking a cigarette certainly added to the allure of the Wm Kearney brand ! Doon Co Limerick 56cm x 50cm

Charming 1940s advert from the merchant bottler Wm Kearney & Sons Limerick City.These bottling merchants would bottle for the major brands such as Jamesons and Bushmills and very often would distill their own single malt whiskey as well, usually for the local market.The "real Irish beauty " featured smoking a cigarette certainly added to the allure of the Wm Kearney brand ! Doon Co Limerick 56cm x 50cm -

Out of stock

John Skelton was born in Armagh in 1925. A very talented artist who delighted in portraying the ordinary men and women of Rural Ireland, his works are on permanent display in the Joyce Collection of Northwestern University of Illinois,the headquarters of the ESB,Bank of Ireland and the Embassy of South Korea. Skelton started his professional career in London, where he came under influence of Euston Road School in the late 1940s. In 1946 he married Caroline, settling four years later in Dublin. He worked initially in advertising as Art Director and illustrator of books, most of them educational. After 1975 he worked full-time as a painter. He had numerous one man shows in Dublin; two in Belfast, one in Los Angeles and one in the Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut. Up to the late 1980s, Skelton was a frequent exhibitor in group shows, particularly the annual Royal Hibernian Academy and the Watercolour Society shows in Dublin. In recent years, however, his work was in such demand that he contributed to these less often. During the 1970s and earlier 1980s he earned a reputation as a gifted teacher and lecturer in the National College of Art and Design in Dublin. John Skelton's grave can be found at Mount Jerome Cemetery, Harold's Cross, Dublin, Ireland. Origins:Co Mayo Dimensions :29cm x 36cm

John Skelton was born in Armagh in 1925. A very talented artist who delighted in portraying the ordinary men and women of Rural Ireland, his works are on permanent display in the Joyce Collection of Northwestern University of Illinois,the headquarters of the ESB,Bank of Ireland and the Embassy of South Korea. Skelton started his professional career in London, where he came under influence of Euston Road School in the late 1940s. In 1946 he married Caroline, settling four years later in Dublin. He worked initially in advertising as Art Director and illustrator of books, most of them educational. After 1975 he worked full-time as a painter. He had numerous one man shows in Dublin; two in Belfast, one in Los Angeles and one in the Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut. Up to the late 1980s, Skelton was a frequent exhibitor in group shows, particularly the annual Royal Hibernian Academy and the Watercolour Society shows in Dublin. In recent years, however, his work was in such demand that he contributed to these less often. During the 1970s and earlier 1980s he earned a reputation as a gifted teacher and lecturer in the National College of Art and Design in Dublin. John Skelton's grave can be found at Mount Jerome Cemetery, Harold's Cross, Dublin, Ireland. Origins:Co Mayo Dimensions :29cm x 36cm