-

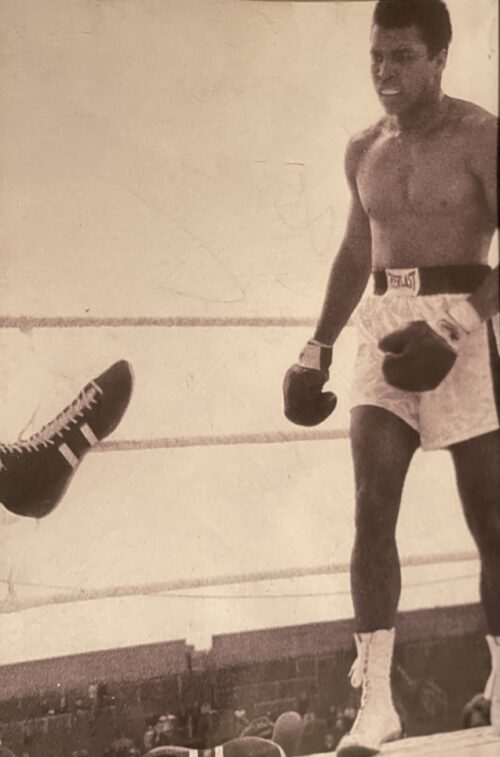

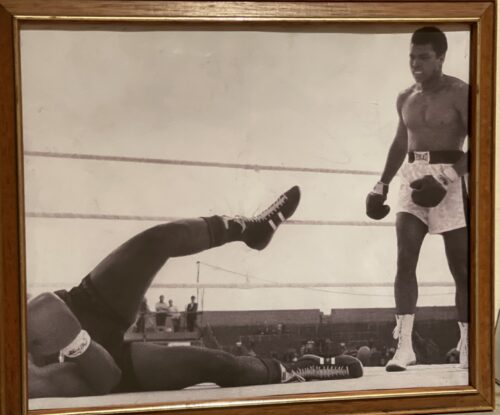

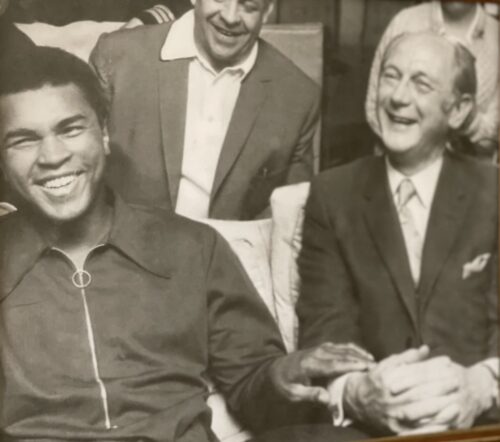

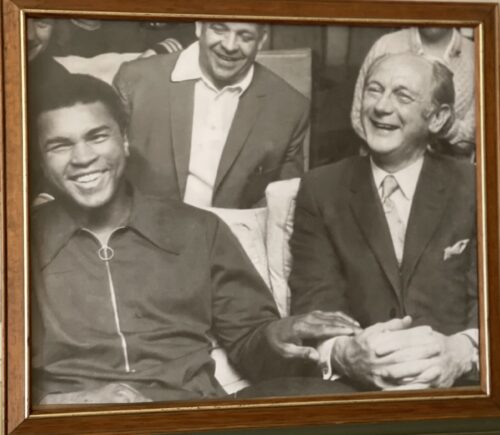

40cm x 34cm July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.

40cm x 34cm July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history. -

40cm x 34cm July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.

40cm x 34cm July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.Muhammad Ali's Irish roots explained

The astonishing fact that he had Irish roots, being descended from Abe Grady, an Irishman from Ennis, County Clare, only became known later in life. He returned to Ireland where he had fought and defeated Al “Blue” Lewis in Croke Park in 1972 almost seven years ago in 2009 to help raise money for his non–profit Muhammad Ali Center, a cultural and educational center in Louisville, Kentucky, and other hospices. He was also there to become the first Freeman of the town. The boxing great is no stranger to Irish shores and previously made a famous trip to Ireland in 1972 when he sat down with Cathal O’Shannon of RTE for a fascinating television interview. What’s more, genealogist Antoinette O'Brien discovered that one of Ali’s great-grandfathers emigrated to the United States from County Clare, meaning that the three-time heavyweight world champion joins the likes of President Obama and Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. as prominent African-Americans with Irish heritage. In the 1860s, Abe Grady left Ennis in County Clare to start a new life in America. He would make his home in Kentucky and marry a free African-American woman. The couple started a family, and one of their daughters was Odessa Lee Grady. Odessa met and married Cassius Clay, Sr. and on January 17, 1942, Cassius junior was born. Cassius Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali when he became a Muslim in 1964. Ali, an Olympic gold medalist at the 1960 games in Rome, has been suffering from Parkinson's for some years but was committed to raising funds for his center During his visit to Clare, he was mobbed by tens of thousands of locals who turned out to meet him and show him the area where his great-grandfather came from.Tracing Muhammad Ali's roots back to County Clare

Historian Dick Eastman had traced Ali’s roots back to Abe Grady the Clare emigrant to Kentucky and the freed slave he married. Eastman wrote: “An 1855 land survey of Ennis, a town in County Clare, Ireland, contains a reference to John Grady, who was renting a house in Turnpike Road in the center of the town. His rent payment was fifteen shillings a month. A few years later, his son Abe Grady immigrated to the United States. He settled in Kentucky." Also, around the year 1855, a man and a woman who were both freed slaves, originally from Liberia, purchased land in or around Duck Lick Creek, Logan, Kentucky. The two married, raised a family and farmed the land. These free blacks went by the name, Morehead, the name of white slave owners of the area. Odessa Grady Clay, Cassius Clay's mother, was the great-granddaughter of the freed slave Tom Morehead and of John Grady of Ennis, whose son Abe had emigrated from Ireland to the United States. She named her son Cassius in honor of a famous Kentucky abolitionist of that time. When he changed his name to Muhammad Ali in 1964, the famous boxer remarked, "Why should I keep my white slavemaster name visible and my black ancestors invisible, unknown, unhonored?" Ali was not only the greatest sporting figure, but he was also the best-known person in the world at his height, revered from Africa to Asia and all over the world. To the end, he was a battler, shown rare courage fighting Parkinson’s Disease, and surviving far longer than most sufferers from the disease.

He was the third leader of Fianna Fáil from 1966 until 1979, succeeding the hugely influential Seán Lemass. Lynch was the last Fianna Fáil leader to secure (in 1977) an overall majority in the Dáil for his party. Historian and journalist T. Ryle Dwyer has called him "the most popular Irish politician since Daniel O'Connell." Before his political career Lynch had a successful sporting career as a dual player of Gaelic games. He played hurlingwith his local club Glen Rovers and with the Cork senior inter-county team from 1936 until 1950. Lynch also played Gaelic football with his local club St Nicholas' and with the Cork senior inter-county team from 1936 until 1946. In a senior inter-county hurling career that lasted for fourteen years he won five All-Ireland titles, seven Munster titles, three National Hurling League titles and seven Railway Cup titles. In a senior inter-county football career that lasted for ten years Lynch won one All-Ireland title, two Munster titles and one Railway Cup title. Lynch was later named at midfield on the Hurling Team of the Century and the Hurling Team of the MillenniumJohn Mary Lynch (15 August 1917 – 20 October 1999), known as Jack Lynch, was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Taoiseach from 1966 to 1973 and 1977 to 1979, Leader of Fianna Fáil from 1966 to 1979, Leader of the Opposition from 1973 to 1977, Minister for Finance from 1965 to 1966, Minister for Industry and Commerce from 1959 to 1965, Minister for Education 1957 to 1959, Minister for the Gaeltacht from March 1957 to June 1957, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Lands and Parliamentary Secretary to the Government from 1951 to 1954. He served as a Teachta Dála (TD) from 1948 to 1981. -

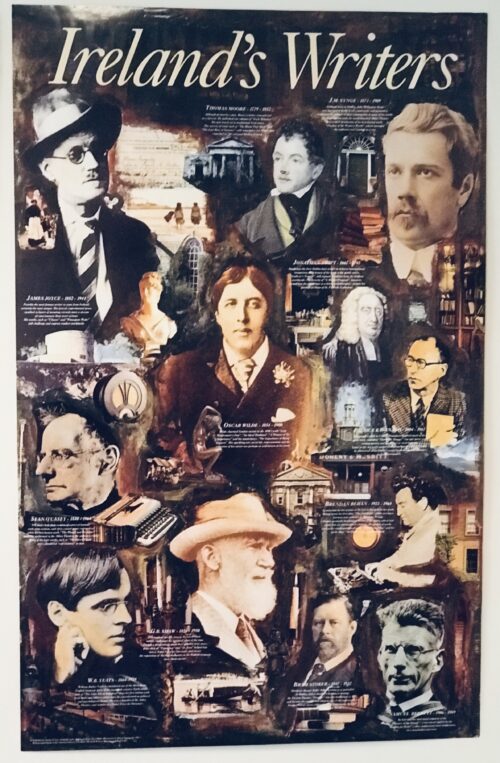

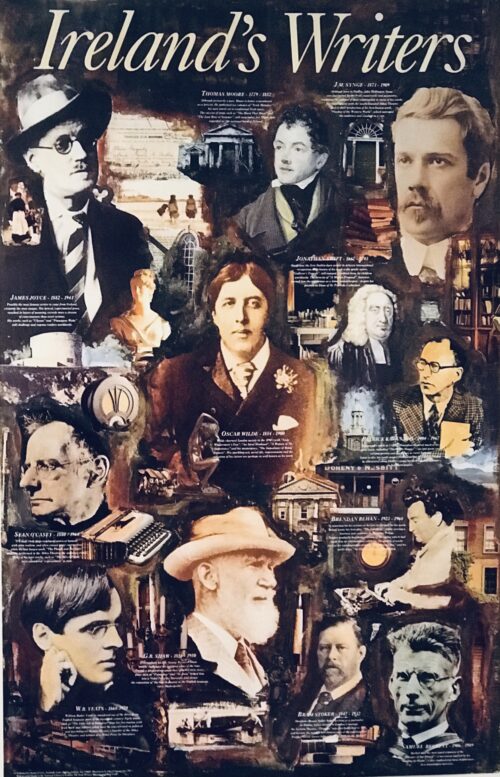

Superb poster depicting the myriad of Irish literary greats throughout the ages -to name but a few,Thomas Moore,JM Synge,WB Yeats,Joyce,Oscar Wilde,Patrick Kavanagh,G.B Shaw etc 84cm x 54cm Irish Literature comprises writings in the Irish, Latin, and English (including Ulster Scots) languages on the island of Ireland. The earliest recorded Irish writing dates from the seventh century and was produced by monks writing in both Latin and Early Irish. In addition to scriptural writing, the monks of Ireland recorded both poetry and mythological tales. There is a large surviving body of Irish mythological writing, including tales such as The Táin and Mad King Sweeny. The English language was introduced to Ireland in the thirteenth century, following the Norman invasion of Ireland. The Irish language, however, remained the dominant language of Irish literature down to the nineteenth century, despite a slow decline which began in the seventeenth century with the expansion of English power. The latter part of the nineteenth century saw a rapid replacement of Irish by English in the greater part of the country. At the end of the century, however, cultural nationalism displayed a new energy, marked by the Gaelic Revival(which encouraged a modern literature in Irish) and more generally by the Irish Literary Revival. The Anglo-Irish literary tradition found its first great exponents in Richard Head and Jonathan Swift followed by Laurence Sterne, Oliver Goldsmith and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. At the end of 19th century and throughout the 20th century, the Irish literature get an unprecedented sequence of worldwide successful works, especially those by Oscar Wilde, Bram Stoker, James Joyce, W. B. Yeats, Samuel Beckett, C.S. Lewis and George Bernard Shaw, prominent writers who left Ireland to make a life in other European countries such as England, France and Switzerland. The descendants of Scottish settlers in Ulster formed the Ulster-Scots writing tradition, having an especially strong tradition of rhyming poetry. Though English was the dominant Irish literary language in the twentieth century, much work of high quality appeared in Irish Gaelic. A pioneering modernist writer in Irish was Pádraic Ó Conaire, and traditional life was given vigorous expression in a series of autobiographies by native Irish speakers from the west coast, exemplified by the work of Tomás Ó Criomhthain and Peig Sayers. The outstanding modernist prose writer in Irish was Máirtín Ó Cadhain, and prominent poets included Máirtín Ó Direáin, Seán Ó Ríordáin and Máire Mhac an tSaoi. Prominent bilingual writers included Brendan Behan (who wrote poetry and a play in Irish) and Flann O'Brien. Two novels by O'Brien, At Swim Two Birdsand The Third Policeman, are considered early examples of postmodern fiction, but he also wrote a satirical novel in Irish called An Béal Bocht(translated as The Poor Mouth). Liam O'Flaherty, who gained fame as a writer in English, also published a book of short stories in Irish (Dúil). Most attention has been given to Irish writers who wrote in English and who were at the forefront of the modernist movement, notably James Joyce, whose novel Ulysses is considered one of the most influential of the century. The playwright Samuel Beckett, in addition to a large amount of prose fiction, wrote a number of important plays, including Waiting for Godot. Several Irish writers have excelled at short story writing, in particular Frank O'Connor and William Trevor. In the late twentieth century Irish poets, especially those from Northern Ireland, came to prominence with Derek Mahon, John Montague, Seamus Heaney and Paul Muldoon. Other notable Irish writers from the twentieth century include, poet Patrick Kavanagh, dramatists Tom Murphy and Brian Friel and novelists Edna O'Brien and John McGahern. Well-known Irish writers in English in the twenty-first century include Colum McCann, Anne Enright, Roddy Doyle, Sebastian Barry, Colm Toibín and John Banville, all of whom have all won major awards. Younger writers include Paul Murray, Kevin Barry, Emma Donoghue, Donal Ryan and dramatist Martin McDonagh. Writing in Irish has also continued to flourish. Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 90cm x 60cm 8kg

Superb poster depicting the myriad of Irish literary greats throughout the ages -to name but a few,Thomas Moore,JM Synge,WB Yeats,Joyce,Oscar Wilde,Patrick Kavanagh,G.B Shaw etc 84cm x 54cm Irish Literature comprises writings in the Irish, Latin, and English (including Ulster Scots) languages on the island of Ireland. The earliest recorded Irish writing dates from the seventh century and was produced by monks writing in both Latin and Early Irish. In addition to scriptural writing, the monks of Ireland recorded both poetry and mythological tales. There is a large surviving body of Irish mythological writing, including tales such as The Táin and Mad King Sweeny. The English language was introduced to Ireland in the thirteenth century, following the Norman invasion of Ireland. The Irish language, however, remained the dominant language of Irish literature down to the nineteenth century, despite a slow decline which began in the seventeenth century with the expansion of English power. The latter part of the nineteenth century saw a rapid replacement of Irish by English in the greater part of the country. At the end of the century, however, cultural nationalism displayed a new energy, marked by the Gaelic Revival(which encouraged a modern literature in Irish) and more generally by the Irish Literary Revival. The Anglo-Irish literary tradition found its first great exponents in Richard Head and Jonathan Swift followed by Laurence Sterne, Oliver Goldsmith and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. At the end of 19th century and throughout the 20th century, the Irish literature get an unprecedented sequence of worldwide successful works, especially those by Oscar Wilde, Bram Stoker, James Joyce, W. B. Yeats, Samuel Beckett, C.S. Lewis and George Bernard Shaw, prominent writers who left Ireland to make a life in other European countries such as England, France and Switzerland. The descendants of Scottish settlers in Ulster formed the Ulster-Scots writing tradition, having an especially strong tradition of rhyming poetry. Though English was the dominant Irish literary language in the twentieth century, much work of high quality appeared in Irish Gaelic. A pioneering modernist writer in Irish was Pádraic Ó Conaire, and traditional life was given vigorous expression in a series of autobiographies by native Irish speakers from the west coast, exemplified by the work of Tomás Ó Criomhthain and Peig Sayers. The outstanding modernist prose writer in Irish was Máirtín Ó Cadhain, and prominent poets included Máirtín Ó Direáin, Seán Ó Ríordáin and Máire Mhac an tSaoi. Prominent bilingual writers included Brendan Behan (who wrote poetry and a play in Irish) and Flann O'Brien. Two novels by O'Brien, At Swim Two Birdsand The Third Policeman, are considered early examples of postmodern fiction, but he also wrote a satirical novel in Irish called An Béal Bocht(translated as The Poor Mouth). Liam O'Flaherty, who gained fame as a writer in English, also published a book of short stories in Irish (Dúil). Most attention has been given to Irish writers who wrote in English and who were at the forefront of the modernist movement, notably James Joyce, whose novel Ulysses is considered one of the most influential of the century. The playwright Samuel Beckett, in addition to a large amount of prose fiction, wrote a number of important plays, including Waiting for Godot. Several Irish writers have excelled at short story writing, in particular Frank O'Connor and William Trevor. In the late twentieth century Irish poets, especially those from Northern Ireland, came to prominence with Derek Mahon, John Montague, Seamus Heaney and Paul Muldoon. Other notable Irish writers from the twentieth century include, poet Patrick Kavanagh, dramatists Tom Murphy and Brian Friel and novelists Edna O'Brien and John McGahern. Well-known Irish writers in English in the twenty-first century include Colum McCann, Anne Enright, Roddy Doyle, Sebastian Barry, Colm Toibín and John Banville, all of whom have all won major awards. Younger writers include Paul Murray, Kevin Barry, Emma Donoghue, Donal Ryan and dramatist Martin McDonagh. Writing in Irish has also continued to flourish. Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 90cm x 60cm 8kg -

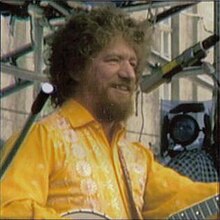

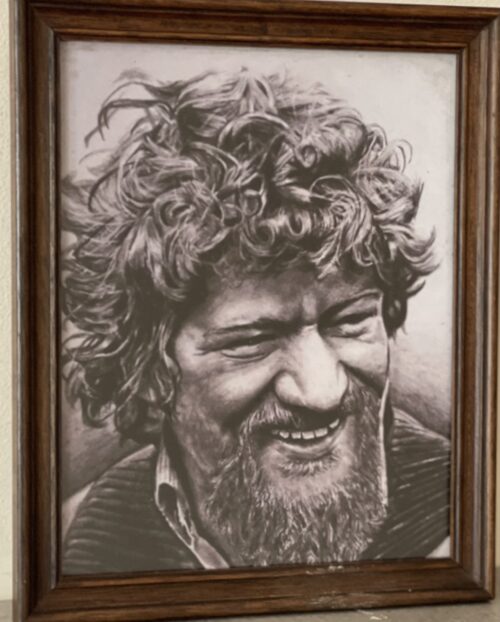

40cm x 30cm Luke Kelly (17 November 1940 – 30 January 1984) was an Irish singer, folk musician and actor from Dublin, Ireland. Born into a working-class household in Dublin city, Kelly moved to England in his late teens and by his early 20s had become involved in a folk music revival. Returning to Dublin in the 1960s, he is noted as a founding member of the band The Dubliners in 1962. Becoming known for his distinctive singing style, and sometimes political messages, the Irish Postand other commentators have regarded Kelly as one of Ireland's greatest folk singers. Early life Luke Kelly was born into a working-class family in Lattimore Cottages at 1 Sheriff Street.His maternal grandmother, who was a MacDonald from Scotland, lived with the family until her death in 1953. His father who was Irish- also named Luke- was shot and severely wounded as a child by British soldiers from the King's Own Scottish Borderers during the 1914 Bachelor's Walk massacre.His father worked all his life in Jacob's biscuit factory and enjoyed playing football. The elder Luke was a keen singer: Luke junior's brother Paddy later recalled that "he had this talent... to sing negro spirituals by people like Paul Robeson, we used to sit around and join in — that was our entertainment". After Dublin Corporation demolished Lattimore Cottages in 1942, the Kellys became the first family to move into the St. Laurence O’Toole flats, where Luke spent the bulk of his childhood, although the family were forced to move by a fire in 1953 and settled in the Whitehall area. Both Luke and Paddy played club Gaelic football and soccer as children. Kelly left school at thirteen and after a number of years of odd-jobbing, he went to England in 1958.[6] Working at steel fixing with his brother Paddy on a building site in Wolverhampton, he was apparently sacked after asking for higher pay. He worked a number of odd jobs, including a period as a vacuum cleaner salesman.Describing himself as a beatnik, he travelled Northern England in search of work, summarising his life in this period as "cleaning lavatories, cleaning windows, cleaning railways, but very rarely cleaning my face".

40cm x 30cm Luke Kelly (17 November 1940 – 30 January 1984) was an Irish singer, folk musician and actor from Dublin, Ireland. Born into a working-class household in Dublin city, Kelly moved to England in his late teens and by his early 20s had become involved in a folk music revival. Returning to Dublin in the 1960s, he is noted as a founding member of the band The Dubliners in 1962. Becoming known for his distinctive singing style, and sometimes political messages, the Irish Postand other commentators have regarded Kelly as one of Ireland's greatest folk singers. Early life Luke Kelly was born into a working-class family in Lattimore Cottages at 1 Sheriff Street.His maternal grandmother, who was a MacDonald from Scotland, lived with the family until her death in 1953. His father who was Irish- also named Luke- was shot and severely wounded as a child by British soldiers from the King's Own Scottish Borderers during the 1914 Bachelor's Walk massacre.His father worked all his life in Jacob's biscuit factory and enjoyed playing football. The elder Luke was a keen singer: Luke junior's brother Paddy later recalled that "he had this talent... to sing negro spirituals by people like Paul Robeson, we used to sit around and join in — that was our entertainment". After Dublin Corporation demolished Lattimore Cottages in 1942, the Kellys became the first family to move into the St. Laurence O’Toole flats, where Luke spent the bulk of his childhood, although the family were forced to move by a fire in 1953 and settled in the Whitehall area. Both Luke and Paddy played club Gaelic football and soccer as children. Kelly left school at thirteen and after a number of years of odd-jobbing, he went to England in 1958.[6] Working at steel fixing with his brother Paddy on a building site in Wolverhampton, he was apparently sacked after asking for higher pay. He worked a number of odd jobs, including a period as a vacuum cleaner salesman.Describing himself as a beatnik, he travelled Northern England in search of work, summarising his life in this period as "cleaning lavatories, cleaning windows, cleaning railways, but very rarely cleaning my face".Musical beginnings

Kelly had been interested in music during his teenage years: he regularly attended céilithe with his sister Mona and listened to American vocalists including: Fats Domino, Al Jolson, Frank Sinatra and Perry Como. He also had an interest in theatre and musicals, being involved with the staging of plays by Dublin's Marian Arts Society. The first folk club he came across was in the Bridge Hotel, Newcastle upon Tyne in early 1960.Having already acquired the use of a banjo, he started memorising songs. In Leeds he brought his banjo to sessions in McReady's pub. The folk revival was under way in England: at the centre of it was Ewan MacColl who scripted a radio programme called Ballads and Blues. A revival in the skiffle genre also injected a certain energy into folk singing at the time. Kelly started busking. On a trip home he went to a fleadh cheoil in Milltown Malbay on the advice of Johnny Moynihan. He listened to recordings of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. He also developed his political convictions which, as Ronnie Drew pointed out after his death, he stuck to throughout his life. As Drew also pointed out, he "learned to sing with perfect diction". Kelly befriended Sean Mulready in Birmingham and lived in his home for a period.Mulready was a teacher who was forced from his job in Dublin because of his communist beliefs. Mulready had strong music links; a sister, Kathleen Moynihan was a founder member of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, and he was related by marriage to Festy Conlon, the County Galway whistle player. Mulready's brother-in-law, Ned Stapleton, taught Kelly "The Rocky Road to Dublin".During this period he studied literature and politics under the tutelage of Mulready, his wife Mollie, and Marxist classicist George Derwent Thomson: Kelly later stated that his interest in music grew parallel to his interest in politics. Kelly bought his first banjo, which had five strings and a long neck, and played it in the style of Pete Seeger and Tommy Makem. At the same time, Kelly began a habit of reading, and also began playing golf on one of Birmingham's municipal courses. He got involved in the Jug O'Punch folk club run by Ian Campbell. He befriended Dominic Behan and they performed in folk clubs and Irish pubs from London to Glasgow. In London pubs, like "The Favourite", he would hear street singer Margaret Barry and musicians in exile like Roger Sherlock, Seamus Ennis, Bobby Casey and Mairtín Byrnes. Luke Kelly was by now active in the Connolly Association, a left-wing grouping strongest among the emigres in England, and he also joined the Young Communist League: he toured Irish pubs playing his set and selling the Connolly Association's newspaper The Irish Democrat. By 1962 George Derwent Thomson had offered him the opportunity to further his educational and political development by attending university in Prague. However, Kelly turned down the offer in favour of pursuing his career in folk music. He was also to start frequenting Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger's Singer Club in London.The Dubliners

In 1961 there was a folk music revival or "ballad boom", as it was later termed, in waiting in Ireland.The Abbey Tavern sessions in Howth were the forerunner to sessions in the Hollybrook, Clontarf, the International Bar and the Grafton Cinema. Luke Kelly returned to Dublin in 1962. O'Donoghue's Pub was already established as a session house and soon Kelly was singing with, among others, Ronnie Drew and Barney McKenna. Other early people playing at O'Donoghues included The Fureys, father and sons, John Keenan and Sean Og McKenna, Johnny Moynihan, Andy Irvine, Seamus Ennis, Willy Clancy and Mairtin Byrnes. A concert John Molloy organised in the Hibernian Hotel led to his "Ballad Tour of Ireland" with the Ronnie Drew Ballad Group (billed in one town as the Ronnie Drew Ballet Group). This tour led to the Abbey Tavern and the Royal Marine Hotel and then to jam-packed sessions in the Embankment, Tallaght. Ciarán Bourke joined the group, followed later by John Sheahan. They renamed themselves The Dubliners at Kelly's suggestion, as he was reading James Joyce's book of short stories, entitled Dubliners, at the time.Kelly was the leading vocalist for the group's eponymous debut album in 1964, which included his rendition of "The Rocky Road to Dublin". Barney McKenna later noted that Kelly was the only singer he'd heard sing it to the rhythm it was played on the fiddle. In 1964 Luke Kelly left the group for nearly two years and was replaced by Bobby Lynch and John Sheahan. Kelly went with Deirdre O'Connell, founder of the Focus Theatre, whom he was to marry the following year, back to London and became involved in Ewan MacColl's "gathering". The Critics, as it was called, was formed to explore folk traditions and help young singers. During this period he retained his political commitments, becoming increasingly active in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Kelly also met and befriended Michael O'Riordan, the General Secretary of the Irish Workers' Party, and the two developed a "personal-political friendship". Kelly endorsed O'Riordan for election, and held a rally in his name during campaigning in 1965.In 1965, he sang 'The Rocky Road to Dublin' with Liam Clancy on his first, self-titled solo album. Bobby Lynch left The Dubliners, John Sheahan and Kelly rejoined. They recorded an album in the Gate Theatre, Dublin, played the Cambridge Folk Festival and recorded Irish Night Out, a live album with, among others, exiles Margaret Barry, Michael Gorman and Jimmy Powers. They also played a concert in the National Stadium in Dublin with Pete Seeger as special guest. They were on the road to success: Top Twenty hits with "Seven Drunken Nights" and "The Black Velvet Band", The Ed Sullivan Show in 1968 and a tour of New Zealand and Australia. The ballad boom in Ireland was becoming increasingly commercialised with bar and pub owners building ever larger venues for pay-in performances. Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger on a visit to Dublin expressed concern to Kelly about his drinking.[citation needed] Christy Moore and Kelly became acquainted in the 1960s.During his Planxty days, Moore got to know Kelly well. In 1972 The Dubliners themselves performed in Richard's Cork Leg, based on the "incomplete works" of Brendan Behan. In 1973, Kelly took to the stage performing as King Herod in Jesus Christ Superstar. The arrival of a new manager for The Dubliners, Derry composer Phil Coulter, resulted in a collaboration that produced three of Kelly's most notable performances: “The Town I Loved So Well”, "Hand me Down my Bible", and “Scorn Not His Simplicity”, a song about Phil's son who had Down Syndrome.Kelly had such respect for the latter song that he only performed it once for a television recording and rarely, if ever, sang it at the Dubliners' often boisterous events. His interpretations of “On Raglan Road” and "Scorn Not His Simplicity" became significant points of reference in Irish folk music.His version of "Raglan Road" came about when the poem's author, Patrick Kavanagh, heard him singing in a Dublin pub, and approached Kelly to say that he should sing the poem (which is set to the tune of “The Dawning of the Day”). Kelly remained a politically engaged musician, becoming a supporter of the movement against South African apartheid and performing at benefit concerts for the Irish Traveller community,and many of the songs he recorded dealt with social issues, the arms race and the Cold War, trade unionism and Irish republicanism, ("The Springhill Disaster", "Joe Hill", "The Button Pusher", "Alabama 1958" and "God Save Ireland" all being examples of his concerns).Personal life

Luke Kelly married Deirdre O'Connell in 1965, but they separated in the early 1970s.Kelly spent the last eight years of his life living with his partner Madeleine Seiler, who is from Germany.Final years

Kelly's health deteriorated in the 1970s. Kelly himself spoke about his problems with alcohol. On 30 June 1980 during a concert in the Cork Opera House he collapsed on the stage. He had already suffered for some time from migraines and forgetfulness - including forgetting what country he was in whilst visiting Iceland - which had been ascribed to his intense schedule, alcohol consumption, and "party lifestyle". A brain tumour was diagnosed.Although Kelly toured with the Dubliners after enduring an operation, his health deteriorated further. He forgot lyrics and had to take longer breaks in concerts as he felt weak. In addition following his emergency surgery after his collapse in Cork, he became more withdrawn, preferring the company of Madeleine at home to performing.On his European tour he managed to perform with the band for most of the show in Carre for their Live in Carre album. However, in autumn 1983 he had to leave the stage in Traun, Austria and again in Mannheim, Germany. Shortly after this, he had to cancel the tour of southern Germany, and after a short stay in hospital in Heidelberg he was flown back to Dublin. After another operation he spent Christmas with his family but was taken into hospital again in the New Year, where he died on 30 January 1984.Kelly's funeral in Whitehall attracted thousands of mourners from across Ireland.His gravestone in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin, bears the inscription: Luke Kelly – Dubliner. Sean Cannon took Kelly's place in The Dubliners. He had been performing with the Dubliners since 1982,due to the deterioration of Kelly's health.Legacy

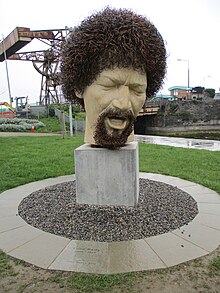

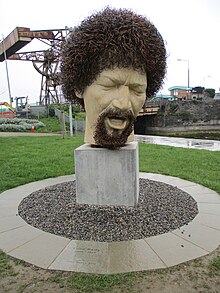

Luke Kelly's legacy and contributions to Irish music and culture have been described as "iconic" and have been captured in a number of documentaries and anthologies. The influence of his Scottish grandmother was influential in Kelly's help in preserving important traditional Scottish songs such as "Mormond Braes", the Canadian folk song "Peggy Gordon", "Robert Burns", "Parcel of Rogues", "Tibbie Dunbar", Hamish Henderson's "Freedom Come-All-Ye", and Thurso Berwick's "Scottish Breakaway". The Ballybough Bridge in the north inner city of Dublin was renamed the Luke Kelly Bridge, and in November 2004 Dublin City Council voted unanimously to erect a bronze statue of Luke Kelly. However, the Dublin Docklands Authority subsequently stated that it could no longer afford to fund the statue. In 2010, councillor Christy Burke of Dublin City Council appealed to members of the music community including Bono, Phil Coulter and Enya to help build it. Paddy Reilly recorded a tribute to Kelly entitled "The Dublin Minstrel". It featured on his Gold And Silver Years, Celtic Collections and the Essential Paddy Reilly CD's. The Dubliners recorded the song on their Live at Vicar Street DVD/CD. The song was composed by Declan O'Donoghue, the Racing Correspondent of The Irish Sun. At Christmas 2005 writer-director Michael Feeney Callan's documentary, Luke Kelly: The Performer, was released and outsold U2's latest DVD during the festive season and into 2006, acquiring platinum sales status. The documentary told Kelly's story through the words of the Dubliners, Donovan, Ralph McTell and others and featured full versions of rarely seen performances such as the early sixties' Ed Sullivan Show. A later documentary, Luke Kelly: Prince of the City, was also well received. Two statues of Kelly were unveiled in Dublin in January 2019, to mark the 35th anniversary of his death.One, a life-size seated bronze by John Coll, is on South King Street. The second sculpture, a marble portrait head by Vera Klute, is on Sheriff Street. The Klute sculpture was vandalised on several occasions in 2019 and 2020, in each case being restored by graffiti-removal specialists. Sculpture of Luke Kelly on Sheriff Street by Vera Klute. Unveiled in 2019

Sculpture of Luke Kelly on Sheriff Street by Vera Klute. Unveiled in 2019 -

40cm x 30cm Luke Kelly (17 November 1940 – 30 January 1984) was an Irish singer, folk musician and actor from Dublin, Ireland. Born into a working-class household in Dublin city, Kelly moved to England in his late teens and by his early 20s had become involved in a folk music revival. Returning to Dublin in the 1960s, he is noted as a founding member of the band The Dubliners in 1962. Becoming known for his distinctive singing style, and sometimes political messages, the Irish Postand other commentators have regarded Kelly as one of Ireland's greatest folk singers. Early life Luke Kelly was born into a working-class family in Lattimore Cottages at 1 Sheriff Street.His maternal grandmother, who was a MacDonald from Scotland, lived with the family until her death in 1953. His father who was Irish- also named Luke- was shot and severely wounded as a child by British soldiers from the King's Own Scottish Borderers during the 1914 Bachelor's Walk massacre.His father worked all his life in Jacob's biscuit factory and enjoyed playing football. The elder Luke was a keen singer: Luke junior's brother Paddy later recalled that "he had this talent... to sing negro spirituals by people like Paul Robeson, we used to sit around and join in — that was our entertainment". After Dublin Corporation demolished Lattimore Cottages in 1942, the Kellys became the first family to move into the St. Laurence O’Toole flats, where Luke spent the bulk of his childhood, although the family were forced to move by a fire in 1953 and settled in the Whitehall area. Both Luke and Paddy played club Gaelic football and soccer as children. Kelly left school at thirteen and after a number of years of odd-jobbing, he went to England in 1958.[6] Working at steel fixing with his brother Paddy on a building site in Wolverhampton, he was apparently sacked after asking for higher pay. He worked a number of odd jobs, including a period as a vacuum cleaner salesman.Describing himself as a beatnik, he travelled Northern England in search of work, summarising his life in this period as "cleaning lavatories, cleaning windows, cleaning railways, but very rarely cleaning my face".

40cm x 30cm Luke Kelly (17 November 1940 – 30 January 1984) was an Irish singer, folk musician and actor from Dublin, Ireland. Born into a working-class household in Dublin city, Kelly moved to England in his late teens and by his early 20s had become involved in a folk music revival. Returning to Dublin in the 1960s, he is noted as a founding member of the band The Dubliners in 1962. Becoming known for his distinctive singing style, and sometimes political messages, the Irish Postand other commentators have regarded Kelly as one of Ireland's greatest folk singers. Early life Luke Kelly was born into a working-class family in Lattimore Cottages at 1 Sheriff Street.His maternal grandmother, who was a MacDonald from Scotland, lived with the family until her death in 1953. His father who was Irish- also named Luke- was shot and severely wounded as a child by British soldiers from the King's Own Scottish Borderers during the 1914 Bachelor's Walk massacre.His father worked all his life in Jacob's biscuit factory and enjoyed playing football. The elder Luke was a keen singer: Luke junior's brother Paddy later recalled that "he had this talent... to sing negro spirituals by people like Paul Robeson, we used to sit around and join in — that was our entertainment". After Dublin Corporation demolished Lattimore Cottages in 1942, the Kellys became the first family to move into the St. Laurence O’Toole flats, where Luke spent the bulk of his childhood, although the family were forced to move by a fire in 1953 and settled in the Whitehall area. Both Luke and Paddy played club Gaelic football and soccer as children. Kelly left school at thirteen and after a number of years of odd-jobbing, he went to England in 1958.[6] Working at steel fixing with his brother Paddy on a building site in Wolverhampton, he was apparently sacked after asking for higher pay. He worked a number of odd jobs, including a period as a vacuum cleaner salesman.Describing himself as a beatnik, he travelled Northern England in search of work, summarising his life in this period as "cleaning lavatories, cleaning windows, cleaning railways, but very rarely cleaning my face".Musical beginnings

Kelly had been interested in music during his teenage years: he regularly attended céilithe with his sister Mona and listened to American vocalists including: Fats Domino, Al Jolson, Frank Sinatra and Perry Como. He also had an interest in theatre and musicals, being involved with the staging of plays by Dublin's Marian Arts Society. The first folk club he came across was in the Bridge Hotel, Newcastle upon Tyne in early 1960.Having already acquired the use of a banjo, he started memorising songs. In Leeds he brought his banjo to sessions in McReady's pub. The folk revival was under way in England: at the centre of it was Ewan MacColl who scripted a radio programme called Ballads and Blues. A revival in the skiffle genre also injected a certain energy into folk singing at the time. Kelly started busking. On a trip home he went to a fleadh cheoil in Milltown Malbay on the advice of Johnny Moynihan. He listened to recordings of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. He also developed his political convictions which, as Ronnie Drew pointed out after his death, he stuck to throughout his life. As Drew also pointed out, he "learned to sing with perfect diction". Kelly befriended Sean Mulready in Birmingham and lived in his home for a period.Mulready was a teacher who was forced from his job in Dublin because of his communist beliefs. Mulready had strong music links; a sister, Kathleen Moynihan was a founder member of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, and he was related by marriage to Festy Conlon, the County Galway whistle player. Mulready's brother-in-law, Ned Stapleton, taught Kelly "The Rocky Road to Dublin".During this period he studied literature and politics under the tutelage of Mulready, his wife Mollie, and Marxist classicist George Derwent Thomson: Kelly later stated that his interest in music grew parallel to his interest in politics. Kelly bought his first banjo, which had five strings and a long neck, and played it in the style of Pete Seeger and Tommy Makem. At the same time, Kelly began a habit of reading, and also began playing golf on one of Birmingham's municipal courses. He got involved in the Jug O'Punch folk club run by Ian Campbell. He befriended Dominic Behan and they performed in folk clubs and Irish pubs from London to Glasgow. In London pubs, like "The Favourite", he would hear street singer Margaret Barry and musicians in exile like Roger Sherlock, Seamus Ennis, Bobby Casey and Mairtín Byrnes. Luke Kelly was by now active in the Connolly Association, a left-wing grouping strongest among the emigres in England, and he also joined the Young Communist League: he toured Irish pubs playing his set and selling the Connolly Association's newspaper The Irish Democrat. By 1962 George Derwent Thomson had offered him the opportunity to further his educational and political development by attending university in Prague. However, Kelly turned down the offer in favour of pursuing his career in folk music. He was also to start frequenting Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger's Singer Club in London.The Dubliners

In 1961 there was a folk music revival or "ballad boom", as it was later termed, in waiting in Ireland.The Abbey Tavern sessions in Howth were the forerunner to sessions in the Hollybrook, Clontarf, the International Bar and the Grafton Cinema. Luke Kelly returned to Dublin in 1962. O'Donoghue's Pub was already established as a session house and soon Kelly was singing with, among others, Ronnie Drew and Barney McKenna. Other early people playing at O'Donoghues included The Fureys, father and sons, John Keenan and Sean Og McKenna, Johnny Moynihan, Andy Irvine, Seamus Ennis, Willy Clancy and Mairtin Byrnes. A concert John Molloy organised in the Hibernian Hotel led to his "Ballad Tour of Ireland" with the Ronnie Drew Ballad Group (billed in one town as the Ronnie Drew Ballet Group). This tour led to the Abbey Tavern and the Royal Marine Hotel and then to jam-packed sessions in the Embankment, Tallaght. Ciarán Bourke joined the group, followed later by John Sheahan. They renamed themselves The Dubliners at Kelly's suggestion, as he was reading James Joyce's book of short stories, entitled Dubliners, at the time.Kelly was the leading vocalist for the group's eponymous debut album in 1964, which included his rendition of "The Rocky Road to Dublin". Barney McKenna later noted that Kelly was the only singer he'd heard sing it to the rhythm it was played on the fiddle. In 1964 Luke Kelly left the group for nearly two years and was replaced by Bobby Lynch and John Sheahan. Kelly went with Deirdre O'Connell, founder of the Focus Theatre, whom he was to marry the following year, back to London and became involved in Ewan MacColl's "gathering". The Critics, as it was called, was formed to explore folk traditions and help young singers. During this period he retained his political commitments, becoming increasingly active in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Kelly also met and befriended Michael O'Riordan, the General Secretary of the Irish Workers' Party, and the two developed a "personal-political friendship". Kelly endorsed O'Riordan for election, and held a rally in his name during campaigning in 1965.In 1965, he sang 'The Rocky Road to Dublin' with Liam Clancy on his first, self-titled solo album. Bobby Lynch left The Dubliners, John Sheahan and Kelly rejoined. They recorded an album in the Gate Theatre, Dublin, played the Cambridge Folk Festival and recorded Irish Night Out, a live album with, among others, exiles Margaret Barry, Michael Gorman and Jimmy Powers. They also played a concert in the National Stadium in Dublin with Pete Seeger as special guest. They were on the road to success: Top Twenty hits with "Seven Drunken Nights" and "The Black Velvet Band", The Ed Sullivan Show in 1968 and a tour of New Zealand and Australia. The ballad boom in Ireland was becoming increasingly commercialised with bar and pub owners building ever larger venues for pay-in performances. Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger on a visit to Dublin expressed concern to Kelly about his drinking.[citation needed] Christy Moore and Kelly became acquainted in the 1960s.During his Planxty days, Moore got to know Kelly well. In 1972 The Dubliners themselves performed in Richard's Cork Leg, based on the "incomplete works" of Brendan Behan. In 1973, Kelly took to the stage performing as King Herod in Jesus Christ Superstar. The arrival of a new manager for The Dubliners, Derry composer Phil Coulter, resulted in a collaboration that produced three of Kelly's most notable performances: “The Town I Loved So Well”, "Hand me Down my Bible", and “Scorn Not His Simplicity”, a song about Phil's son who had Down Syndrome.Kelly had such respect for the latter song that he only performed it once for a television recording and rarely, if ever, sang it at the Dubliners' often boisterous events. His interpretations of “On Raglan Road” and "Scorn Not His Simplicity" became significant points of reference in Irish folk music.His version of "Raglan Road" came about when the poem's author, Patrick Kavanagh, heard him singing in a Dublin pub, and approached Kelly to say that he should sing the poem (which is set to the tune of “The Dawning of the Day”). Kelly remained a politically engaged musician, becoming a supporter of the movement against South African apartheid and performing at benefit concerts for the Irish Traveller community,and many of the songs he recorded dealt with social issues, the arms race and the Cold War, trade unionism and Irish republicanism, ("The Springhill Disaster", "Joe Hill", "The Button Pusher", "Alabama 1958" and "God Save Ireland" all being examples of his concerns).Personal life

Luke Kelly married Deirdre O'Connell in 1965, but they separated in the early 1970s.Kelly spent the last eight years of his life living with his partner Madeleine Seiler, who is from Germany.Final years

Kelly's health deteriorated in the 1970s. Kelly himself spoke about his problems with alcohol. On 30 June 1980 during a concert in the Cork Opera House he collapsed on the stage. He had already suffered for some time from migraines and forgetfulness - including forgetting what country he was in whilst visiting Iceland - which had been ascribed to his intense schedule, alcohol consumption, and "party lifestyle". A brain tumour was diagnosed.Although Kelly toured with the Dubliners after enduring an operation, his health deteriorated further. He forgot lyrics and had to take longer breaks in concerts as he felt weak. In addition following his emergency surgery after his collapse in Cork, he became more withdrawn, preferring the company of Madeleine at home to performing.On his European tour he managed to perform with the band for most of the show in Carre for their Live in Carre album. However, in autumn 1983 he had to leave the stage in Traun, Austria and again in Mannheim, Germany. Shortly after this, he had to cancel the tour of southern Germany, and after a short stay in hospital in Heidelberg he was flown back to Dublin. After another operation he spent Christmas with his family but was taken into hospital again in the New Year, where he died on 30 January 1984.Kelly's funeral in Whitehall attracted thousands of mourners from across Ireland.His gravestone in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin, bears the inscription: Luke Kelly – Dubliner. Sean Cannon took Kelly's place in The Dubliners. He had been performing with the Dubliners since 1982,due to the deterioration of Kelly's health.Legacy

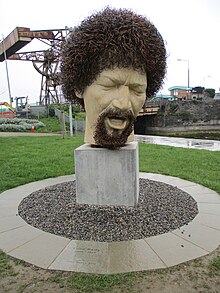

Luke Kelly's legacy and contributions to Irish music and culture have been described as "iconic" and have been captured in a number of documentaries and anthologies. The influence of his Scottish grandmother was influential in Kelly's help in preserving important traditional Scottish songs such as "Mormond Braes", the Canadian folk song "Peggy Gordon", "Robert Burns", "Parcel of Rogues", "Tibbie Dunbar", Hamish Henderson's "Freedom Come-All-Ye", and Thurso Berwick's "Scottish Breakaway". The Ballybough Bridge in the north inner city of Dublin was renamed the Luke Kelly Bridge, and in November 2004 Dublin City Council voted unanimously to erect a bronze statue of Luke Kelly. However, the Dublin Docklands Authority subsequently stated that it could no longer afford to fund the statue. In 2010, councillor Christy Burke of Dublin City Council appealed to members of the music community including Bono, Phil Coulter and Enya to help build it. Paddy Reilly recorded a tribute to Kelly entitled "The Dublin Minstrel". It featured on his Gold And Silver Years, Celtic Collections and the Essential Paddy Reilly CD's. The Dubliners recorded the song on their Live at Vicar Street DVD/CD. The song was composed by Declan O'Donoghue, the Racing Correspondent of The Irish Sun. At Christmas 2005 writer-director Michael Feeney Callan's documentary, Luke Kelly: The Performer, was released and outsold U2's latest DVD during the festive season and into 2006, acquiring platinum sales status. The documentary told Kelly's story through the words of the Dubliners, Donovan, Ralph McTell and others and featured full versions of rarely seen performances such as the early sixties' Ed Sullivan Show. A later documentary, Luke Kelly: Prince of the City, was also well received. Two statues of Kelly were unveiled in Dublin in January 2019, to mark the 35th anniversary of his death.One, a life-size seated bronze by John Coll, is on South King Street. The second sculpture, a marble portrait head by Vera Klute, is on Sheriff Street. The Klute sculpture was vandalised on several occasions in 2019 and 2020, in each case being restored by graffiti-removal specialists. Sculpture of Luke Kelly on Sheriff Street by Vera Klute. Unveiled in 2019

Sculpture of Luke Kelly on Sheriff Street by Vera Klute. Unveiled in 2019 -

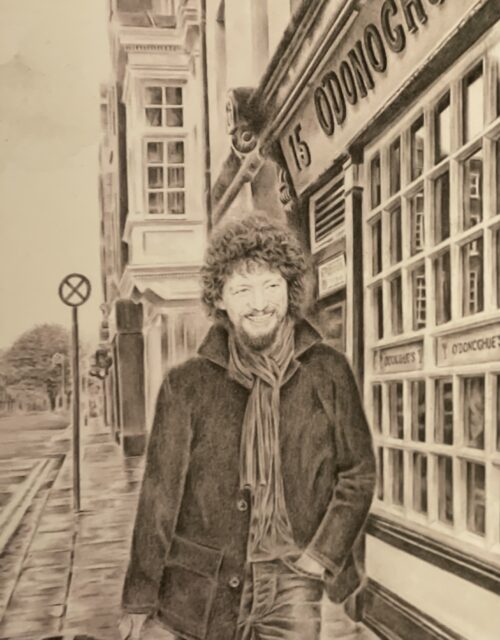

55cm x 45cm Luke Kelly (17 November 1940 – 30 January 1984) was an Irish singer, folk musician and actor from Dublin, Ireland. Born into a working-class household in Dublin city, Kelly moved to England in his late teens and by his early 20s had become involved in a folk music revival. Returning to Dublin in the 1960s, he is noted as a founding member of the band The Dubliners in 1962. Becoming known for his distinctive singing style, and sometimes political messages, the Irish Postand other commentators have regarded Kelly as one of Ireland's greatest folk singers. Early life Luke Kelly was born into a working-class family in Lattimore Cottages at 1 Sheriff Street.His maternal grandmother, who was a MacDonald from Scotland, lived with the family until her death in 1953. His father who was Irish- also named Luke- was shot and severely wounded as a child by British soldiers from the King's Own Scottish Borderers during the 1914 Bachelor's Walk massacre.His father worked all his life in Jacob's biscuit factory and enjoyed playing football. The elder Luke was a keen singer: Luke junior's brother Paddy later recalled that "he had this talent... to sing negro spirituals by people like Paul Robeson, we used to sit around and join in — that was our entertainment". After Dublin Corporation demolished Lattimore Cottages in 1942, the Kellys became the first family to move into the St. Laurence O’Toole flats, where Luke spent the bulk of his childhood, although the family were forced to move by a fire in 1953 and settled in the Whitehall area. Both Luke and Paddy played club Gaelic football and soccer as children. Kelly left school at thirteen and after a number of years of odd-jobbing, he went to England in 1958.[6] Working at steel fixing with his brother Paddy on a building site in Wolverhampton, he was apparently sacked after asking for higher pay. He worked a number of odd jobs, including a period as a vacuum cleaner salesman.Describing himself as a beatnik, he travelled Northern England in search of work, summarising his life in this period as "cleaning lavatories, cleaning windows, cleaning railways, but very rarely cleaning my face".

55cm x 45cm Luke Kelly (17 November 1940 – 30 January 1984) was an Irish singer, folk musician and actor from Dublin, Ireland. Born into a working-class household in Dublin city, Kelly moved to England in his late teens and by his early 20s had become involved in a folk music revival. Returning to Dublin in the 1960s, he is noted as a founding member of the band The Dubliners in 1962. Becoming known for his distinctive singing style, and sometimes political messages, the Irish Postand other commentators have regarded Kelly as one of Ireland's greatest folk singers. Early life Luke Kelly was born into a working-class family in Lattimore Cottages at 1 Sheriff Street.His maternal grandmother, who was a MacDonald from Scotland, lived with the family until her death in 1953. His father who was Irish- also named Luke- was shot and severely wounded as a child by British soldiers from the King's Own Scottish Borderers during the 1914 Bachelor's Walk massacre.His father worked all his life in Jacob's biscuit factory and enjoyed playing football. The elder Luke was a keen singer: Luke junior's brother Paddy later recalled that "he had this talent... to sing negro spirituals by people like Paul Robeson, we used to sit around and join in — that was our entertainment". After Dublin Corporation demolished Lattimore Cottages in 1942, the Kellys became the first family to move into the St. Laurence O’Toole flats, where Luke spent the bulk of his childhood, although the family were forced to move by a fire in 1953 and settled in the Whitehall area. Both Luke and Paddy played club Gaelic football and soccer as children. Kelly left school at thirteen and after a number of years of odd-jobbing, he went to England in 1958.[6] Working at steel fixing with his brother Paddy on a building site in Wolverhampton, he was apparently sacked after asking for higher pay. He worked a number of odd jobs, including a period as a vacuum cleaner salesman.Describing himself as a beatnik, he travelled Northern England in search of work, summarising his life in this period as "cleaning lavatories, cleaning windows, cleaning railways, but very rarely cleaning my face".Musical beginnings

Kelly had been interested in music during his teenage years: he regularly attended céilithe with his sister Mona and listened to American vocalists including: Fats Domino, Al Jolson, Frank Sinatra and Perry Como. He also had an interest in theatre and musicals, being involved with the staging of plays by Dublin's Marian Arts Society. The first folk club he came across was in the Bridge Hotel, Newcastle upon Tyne in early 1960.Having already acquired the use of a banjo, he started memorising songs. In Leeds he brought his banjo to sessions in McReady's pub. The folk revival was under way in England: at the centre of it was Ewan MacColl who scripted a radio programme called Ballads and Blues. A revival in the skiffle genre also injected a certain energy into folk singing at the time. Kelly started busking. On a trip home he went to a fleadh cheoil in Milltown Malbay on the advice of Johnny Moynihan. He listened to recordings of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. He also developed his political convictions which, as Ronnie Drew pointed out after his death, he stuck to throughout his life. As Drew also pointed out, he "learned to sing with perfect diction". Kelly befriended Sean Mulready in Birmingham and lived in his home for a period.Mulready was a teacher who was forced from his job in Dublin because of his communist beliefs. Mulready had strong music links; a sister, Kathleen Moynihan was a founder member of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, and he was related by marriage to Festy Conlon, the County Galway whistle player. Mulready's brother-in-law, Ned Stapleton, taught Kelly "The Rocky Road to Dublin".During this period he studied literature and politics under the tutelage of Mulready, his wife Mollie, and Marxist classicist George Derwent Thomson: Kelly later stated that his interest in music grew parallel to his interest in politics. Kelly bought his first banjo, which had five strings and a long neck, and played it in the style of Pete Seeger and Tommy Makem. At the same time, Kelly began a habit of reading, and also began playing golf on one of Birmingham's municipal courses. He got involved in the Jug O'Punch folk club run by Ian Campbell. He befriended Dominic Behan and they performed in folk clubs and Irish pubs from London to Glasgow. In London pubs, like "The Favourite", he would hear street singer Margaret Barry and musicians in exile like Roger Sherlock, Seamus Ennis, Bobby Casey and Mairtín Byrnes. Luke Kelly was by now active in the Connolly Association, a left-wing grouping strongest among the emigres in England, and he also joined the Young Communist League: he toured Irish pubs playing his set and selling the Connolly Association's newspaper The Irish Democrat. By 1962 George Derwent Thomson had offered him the opportunity to further his educational and political development by attending university in Prague. However, Kelly turned down the offer in favour of pursuing his career in folk music. He was also to start frequenting Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger's Singer Club in London.The Dubliners

In 1961 there was a folk music revival or "ballad boom", as it was later termed, in waiting in Ireland.The Abbey Tavern sessions in Howth were the forerunner to sessions in the Hollybrook, Clontarf, the International Bar and the Grafton Cinema. Luke Kelly returned to Dublin in 1962. O'Donoghue's Pub was already established as a session house and soon Kelly was singing with, among others, Ronnie Drew and Barney McKenna. Other early people playing at O'Donoghues included The Fureys, father and sons, John Keenan and Sean Og McKenna, Johnny Moynihan, Andy Irvine, Seamus Ennis, Willy Clancy and Mairtin Byrnes. A concert John Molloy organised in the Hibernian Hotel led to his "Ballad Tour of Ireland" with the Ronnie Drew Ballad Group (billed in one town as the Ronnie Drew Ballet Group). This tour led to the Abbey Tavern and the Royal Marine Hotel and then to jam-packed sessions in the Embankment, Tallaght. Ciarán Bourke joined the group, followed later by John Sheahan. They renamed themselves The Dubliners at Kelly's suggestion, as he was reading James Joyce's book of short stories, entitled Dubliners, at the time.Kelly was the leading vocalist for the group's eponymous debut album in 1964, which included his rendition of "The Rocky Road to Dublin". Barney McKenna later noted that Kelly was the only singer he'd heard sing it to the rhythm it was played on the fiddle. In 1964 Luke Kelly left the group for nearly two years and was replaced by Bobby Lynch and John Sheahan. Kelly went with Deirdre O'Connell, founder of the Focus Theatre, whom he was to marry the following year, back to London and became involved in Ewan MacColl's "gathering". The Critics, as it was called, was formed to explore folk traditions and help young singers. During this period he retained his political commitments, becoming increasingly active in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Kelly also met and befriended Michael O'Riordan, the General Secretary of the Irish Workers' Party, and the two developed a "personal-political friendship". Kelly endorsed O'Riordan for election, and held a rally in his name during campaigning in 1965.In 1965, he sang 'The Rocky Road to Dublin' with Liam Clancy on his first, self-titled solo album. Bobby Lynch left The Dubliners, John Sheahan and Kelly rejoined. They recorded an album in the Gate Theatre, Dublin, played the Cambridge Folk Festival and recorded Irish Night Out, a live album with, among others, exiles Margaret Barry, Michael Gorman and Jimmy Powers. They also played a concert in the National Stadium in Dublin with Pete Seeger as special guest. They were on the road to success: Top Twenty hits with "Seven Drunken Nights" and "The Black Velvet Band", The Ed Sullivan Show in 1968 and a tour of New Zealand and Australia. The ballad boom in Ireland was becoming increasingly commercialised with bar and pub owners building ever larger venues for pay-in performances. Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger on a visit to Dublin expressed concern to Kelly about his drinking.[citation needed] Christy Moore and Kelly became acquainted in the 1960s.During his Planxty days, Moore got to know Kelly well. In 1972 The Dubliners themselves performed in Richard's Cork Leg, based on the "incomplete works" of Brendan Behan. In 1973, Kelly took to the stage performing as King Herod in Jesus Christ Superstar. The arrival of a new manager for The Dubliners, Derry composer Phil Coulter, resulted in a collaboration that produced three of Kelly's most notable performances: “The Town I Loved So Well”, "Hand me Down my Bible", and “Scorn Not His Simplicity”, a song about Phil's son who had Down Syndrome.Kelly had such respect for the latter song that he only performed it once for a television recording and rarely, if ever, sang it at the Dubliners' often boisterous events. His interpretations of “On Raglan Road” and "Scorn Not His Simplicity" became significant points of reference in Irish folk music.His version of "Raglan Road" came about when the poem's author, Patrick Kavanagh, heard him singing in a Dublin pub, and approached Kelly to say that he should sing the poem (which is set to the tune of “The Dawning of the Day”). Kelly remained a politically engaged musician, becoming a supporter of the movement against South African apartheid and performing at benefit concerts for the Irish Traveller community,and many of the songs he recorded dealt with social issues, the arms race and the Cold War, trade unionism and Irish republicanism, ("The Springhill Disaster", "Joe Hill", "The Button Pusher", "Alabama 1958" and "God Save Ireland" all being examples of his concerns).Personal life

Luke Kelly married Deirdre O'Connell in 1965, but they separated in the early 1970s.Kelly spent the last eight years of his life living with his partner Madeleine Seiler, who is from Germany.Final years

Kelly's health deteriorated in the 1970s. Kelly himself spoke about his problems with alcohol. On 30 June 1980 during a concert in the Cork Opera House he collapsed on the stage. He had already suffered for some time from migraines and forgetfulness - including forgetting what country he was in whilst visiting Iceland - which had been ascribed to his intense schedule, alcohol consumption, and "party lifestyle". A brain tumour was diagnosed.Although Kelly toured with the Dubliners after enduring an operation, his health deteriorated further. He forgot lyrics and had to take longer breaks in concerts as he felt weak. In addition following his emergency surgery after his collapse in Cork, he became more withdrawn, preferring the company of Madeleine at home to performing.On his European tour he managed to perform with the band for most of the show in Carre for their Live in Carre album. However, in autumn 1983 he had to leave the stage in Traun, Austria and again in Mannheim, Germany. Shortly after this, he had to cancel the tour of southern Germany, and after a short stay in hospital in Heidelberg he was flown back to Dublin. After another operation he spent Christmas with his family but was taken into hospital again in the New Year, where he died on 30 January 1984.Kelly's funeral in Whitehall attracted thousands of mourners from across Ireland.His gravestone in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin, bears the inscription: Luke Kelly – Dubliner. Sean Cannon took Kelly's place in The Dubliners. He had been performing with the Dubliners since 1982,due to the deterioration of Kelly's health.Legacy

Luke Kelly's legacy and contributions to Irish music and culture have been described as "iconic" and have been captured in a number of documentaries and anthologies. The influence of his Scottish grandmother was influential in Kelly's help in preserving important traditional Scottish songs such as "Mormond Braes", the Canadian folk song "Peggy Gordon", "Robert Burns", "Parcel of Rogues", "Tibbie Dunbar", Hamish Henderson's "Freedom Come-All-Ye", and Thurso Berwick's "Scottish Breakaway". The Ballybough Bridge in the north inner city of Dublin was renamed the Luke Kelly Bridge, and in November 2004 Dublin City Council voted unanimously to erect a bronze statue of Luke Kelly. However, the Dublin Docklands Authority subsequently stated that it could no longer afford to fund the statue. In 2010, councillor Christy Burke of Dublin City Council appealed to members of the music community including Bono, Phil Coulter and Enya to help build it. Paddy Reilly recorded a tribute to Kelly entitled "The Dublin Minstrel". It featured on his Gold And Silver Years, Celtic Collections and the Essential Paddy Reilly CD's. The Dubliners recorded the song on their Live at Vicar Street DVD/CD. The song was composed by Declan O'Donoghue, the Racing Correspondent of The Irish Sun. At Christmas 2005 writer-director Michael Feeney Callan's documentary, Luke Kelly: The Performer, was released and outsold U2's latest DVD during the festive season and into 2006, acquiring platinum sales status. The documentary told Kelly's story through the words of the Dubliners, Donovan, Ralph McTell and others and featured full versions of rarely seen performances such as the early sixties' Ed Sullivan Show. A later documentary, Luke Kelly: Prince of the City, was also well received. Two statues of Kelly were unveiled in Dublin in January 2019, to mark the 35th anniversary of his death.One, a life-size seated bronze by John Coll, is on South King Street. The second sculpture, a marble portrait head by Vera Klute, is on Sheriff Street. The Klute sculpture was vandalised on several occasions in 2019 and 2020, in each case being restored by graffiti-removal specialists. Sculpture of Luke Kelly on Sheriff Street by Vera Klute. Unveiled in 2019

Sculpture of Luke Kelly on Sheriff Street by Vera Klute. Unveiled in 2019 -

32cm x 27cm

32cm x 27cmTHE famous comedy team of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy were scheduled to disembark from the liner ‘America’ which called at Cobh today from New York. No elaborate reception was planned, and the shipping officials carried out the usual arrangements for the arrival of important passengers.

The famous pair wanted no fuss, and of course, the liner company officals were anxious to carry out to the letter the wishes of their first-class passengers.

Mr Sean O’Brien, Irish manager of US Lines, said his officials were there to greet them and satisfy their slightest wish.

But often on the occasion when the planning is most careful, something goes wrong. And in this case it did. For neither the comedians, nor their wives, nor the company officials, nor the police nor the many other people associated with the life of a trans- Atlantic port of call, reckoned with the children, to whom the funny faces and the queer screen antics of the cuckoo comedians is better known than the president of the US.

The entire children’s population of Cobh must have played truant from school for they blocked all traffic, and despite the presence of several vastly amused policemen, they clung onto Laurel and Hardy.

They begged for autographs, ruffled their ties and generally gave them a whole-hearted reception.

Non-plussed, but only for a moment, the comedians entered into the fun of the affair, and nobody could accuse them of being stinted in giving autographs.

Twenty-three stone Hardy (22st 12lbs to be exact) commented: “We were absolutely overwhelmed. There scarcely ever was a film scene like it. They are grand children, and Stan and I are grateful to them.”

There was no great advance publicity, but all of Cobh and outlying districts seemed to know that Laurel and Hardy had arrived. Family parties went out in small boats and cheered as the tender bearing the passengers from the liner drew into the quayside.

The party were taken by Mr O’Brien to hear the carillon bells of Cobh Cathedral and the comedians told an Echo reporter that hearing the ‘Cuckoo Song’ played on the bells was one of the greatest thrills of their lives.

Later, the party went to kiss the Blarney Stone. All performed the traditional rite of kissing except Hardy, who commented: “Nobody would hold me. I am too big.”

Ald P McGrath, Lord Mayor of Cork, accompanied by Mr AA Healy, TC, received them at the City Hall and was photographed with them. Asked to nominate their favourite film the bluff Oliver replied: “Fra Diavolo.”

They have been partners for thirty years. Subsequently the comedians and their wives left for Dublin where they are to fulfil a theatrical engagement.

Amongst the others who met them in Cobh was Mrs D Murphy, on behalf of Mr George Heffernan, Tourist Agent, Cork.

Another passenger to disembark from the vessel was the Hon Kit Clardy, Republican Senator from Michigan. He intends to spend a short holiday in this country. In all, 117 disembarked at Cobh.

Embarking passengers included a party of 40 pilgrims from Cork to Lourdes and Liseux. The spiritual director to the party is Rev Maurice Walsh, SMA, and the pilgrimage arrangements were in the hands of Miss B Arnold, of Mr Heffernan’s agency.

-