-

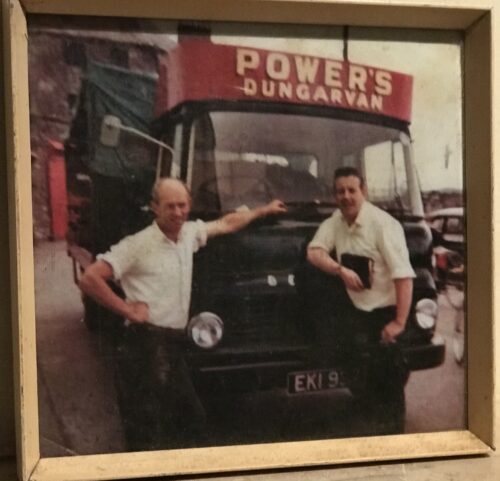

Charming framed photo from the 1960s of two Powers of dungarvan workers alongside a delivery lorry. 22cm x 23cm Thomas Power (1856-1930) was the first chairman of Waterford County Council and was chairman of Dungarvan Town Commissioners on a number of occasions. In the 1880s he was in partnership with his brother producing mineral waters. In 1904 he began producing his award winning Blackwater Cider. In 1917 Thomas purchased the old St Brigid's Well Brewery in Fair Lane, Dungarvan from the Marquis of Waterford. The business was a great success and its produce was in demand all over County Waterford and beyond. After his death the brewery was taken over by his son Paul I. Power who managed it until 1976 when his son Ion took over. Brewing took place in Dungarvan throughout history but we only have detailed information from the late 18th century onwards. In 1917 the Marquis sold the property and it was acquired by Thomas Power. He developed a thriving business known as Power's Brewery. This brewing tradition continues into the modern era with the Dungarvan Brewing Company.

Charming framed photo from the 1960s of two Powers of dungarvan workers alongside a delivery lorry. 22cm x 23cm Thomas Power (1856-1930) was the first chairman of Waterford County Council and was chairman of Dungarvan Town Commissioners on a number of occasions. In the 1880s he was in partnership with his brother producing mineral waters. In 1904 he began producing his award winning Blackwater Cider. In 1917 Thomas purchased the old St Brigid's Well Brewery in Fair Lane, Dungarvan from the Marquis of Waterford. The business was a great success and its produce was in demand all over County Waterford and beyond. After his death the brewery was taken over by his son Paul I. Power who managed it until 1976 when his son Ion took over. Brewing took place in Dungarvan throughout history but we only have detailed information from the late 18th century onwards. In 1917 the Marquis sold the property and it was acquired by Thomas Power. He developed a thriving business known as Power's Brewery. This brewing tradition continues into the modern era with the Dungarvan Brewing Company. -

Out of stock

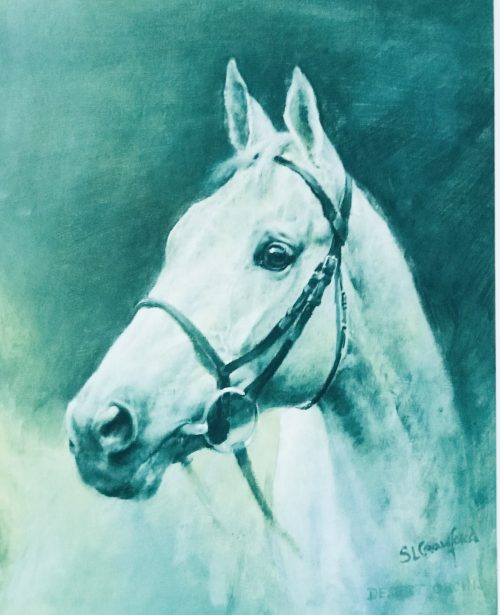

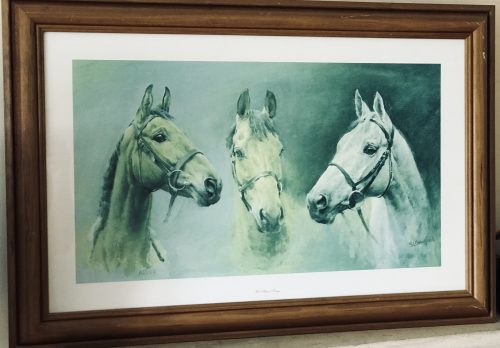

Beautiful print of three all time great National Hunt Horses : Arkle,Red Rum and Desert Orchid by the artist SL Crawford 60cmx 85cm Lucan Co Dublin

Beautiful print of three all time great National Hunt Horses : Arkle,Red Rum and Desert Orchid by the artist SL Crawford 60cmx 85cm Lucan Co Dublin -

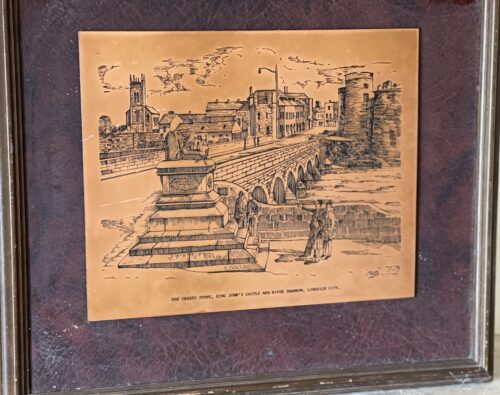

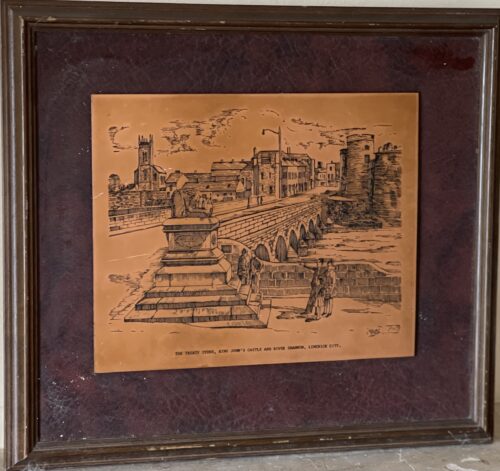

34cm x 39cm Limerick CityThe Treaty Stone is the rock that the Treaty of Limerick was signed in 1691, marking the surrender of the city to William of Orange.King John's Castle is a 13th-century castle located on King's Island in Limerick, Ireland, next to the River Shannon.Although the site dates back to 922 when the Vikings lived on the Island, the castle itself was built on the orders of King John in 1200. One of the best preserved Norman castles in Europe, the walls, towers and fortifications remain today and are visitor attractions. The remains of a Viking settlement were uncovered during archaeological excavations at the site in 1900. Thomondgate was part of the “Northern” Liberties granted to Limerick in 1216. This area was the border between Munster and Connacht until County Clare, which was created in 1565, was annexed by Munster in 1602. TheThomondgate bridge was originally built in 1185 on the orders of King John and is said to have cost the hefty sum of £30. As a result of poor workmanship the bridge collapsed in 1292 causing the deaths of 80 people. Soon after, the bridge was rebuilt with the addition of two gate towers, one at each end. It partially collapsed in 1833 as a result of bad weather and was replaced with a bridge designed by brothers James and George Pain at a cost of £10,000.Limerick is known as the Treaty City, so called after the Treaty of Limerick signed on the 3rd of October 1691 after the war between William III of England (known as William of Orange) and his Father in Law King James II. Limericks role in the successful accession of William of Orange and his wife Mary Stuart, daughter of King James II to the throne of England cannot be understated. The Treaty, according to tradition was signed on a stone in the sight of both armies at the Clare end of Thomond Bridge on the 3rd of October 1691. The stone was for some years resting on the ground opposite its present location, where the old Ennis mail coach left to travel from the Clare end of Thomond Bridge, through Cratloe woods en route to Ennis. The Treaty stone of Limerick has rested on a plinth since 1865, at the Clare end of Thomond Bridge. The pedestal was erected in May 1865 by John Richard Tinsley, mayor of the city.

34cm x 39cm Limerick CityThe Treaty Stone is the rock that the Treaty of Limerick was signed in 1691, marking the surrender of the city to William of Orange.King John's Castle is a 13th-century castle located on King's Island in Limerick, Ireland, next to the River Shannon.Although the site dates back to 922 when the Vikings lived on the Island, the castle itself was built on the orders of King John in 1200. One of the best preserved Norman castles in Europe, the walls, towers and fortifications remain today and are visitor attractions. The remains of a Viking settlement were uncovered during archaeological excavations at the site in 1900. Thomondgate was part of the “Northern” Liberties granted to Limerick in 1216. This area was the border between Munster and Connacht until County Clare, which was created in 1565, was annexed by Munster in 1602. TheThomondgate bridge was originally built in 1185 on the orders of King John and is said to have cost the hefty sum of £30. As a result of poor workmanship the bridge collapsed in 1292 causing the deaths of 80 people. Soon after, the bridge was rebuilt with the addition of two gate towers, one at each end. It partially collapsed in 1833 as a result of bad weather and was replaced with a bridge designed by brothers James and George Pain at a cost of £10,000.Limerick is known as the Treaty City, so called after the Treaty of Limerick signed on the 3rd of October 1691 after the war between William III of England (known as William of Orange) and his Father in Law King James II. Limericks role in the successful accession of William of Orange and his wife Mary Stuart, daughter of King James II to the throne of England cannot be understated. The Treaty, according to tradition was signed on a stone in the sight of both armies at the Clare end of Thomond Bridge on the 3rd of October 1691. The stone was for some years resting on the ground opposite its present location, where the old Ennis mail coach left to travel from the Clare end of Thomond Bridge, through Cratloe woods en route to Ennis. The Treaty stone of Limerick has rested on a plinth since 1865, at the Clare end of Thomond Bridge. The pedestal was erected in May 1865 by John Richard Tinsley, mayor of the city. -

Tullamore Dew advert 40cm x 30cm Banagher Co Offaly Tullamore D.E.W. is a brand of Irish whiskey produced by William Grant & Sons. It is the second largest selling brand of Irish whiskey globally, with sales of over 950,000 cases per annum as of 2015.The whiskey was originally produced in the Tullamore, County Offaly, Ireland, at the old Tullamore Distillery which was established in 1829. Its name is derived from the initials of Daniel E. Williams (D.E.W.), a general manager and later owner of the original distillery. In 1954, the original distillery closed down, and with stocks of whiskey running low, the brand was sold to John Powers & Son, another Irish distiller in the 1960s, with production transferred to the Midleton Distillery, County Cork in the 1970s following a merger of three major Irish distillers.In 2010, the brand was purchased by William Grant & Sons, who constructed a new distillery on the outskirts of Tullamore. The new distillery opened in 2014, bringing production of the whiskey back to the town after a break of sixty years.

Tullamore Dew advert 40cm x 30cm Banagher Co Offaly Tullamore D.E.W. is a brand of Irish whiskey produced by William Grant & Sons. It is the second largest selling brand of Irish whiskey globally, with sales of over 950,000 cases per annum as of 2015.The whiskey was originally produced in the Tullamore, County Offaly, Ireland, at the old Tullamore Distillery which was established in 1829. Its name is derived from the initials of Daniel E. Williams (D.E.W.), a general manager and later owner of the original distillery. In 1954, the original distillery closed down, and with stocks of whiskey running low, the brand was sold to John Powers & Son, another Irish distiller in the 1960s, with production transferred to the Midleton Distillery, County Cork in the 1970s following a merger of three major Irish distillers.In 2010, the brand was purchased by William Grant & Sons, who constructed a new distillery on the outskirts of Tullamore. The new distillery opened in 2014, bringing production of the whiskey back to the town after a break of sixty years.Mick The Miller,as featured in this iconic advert, was the most famous greyhound of all time. He was born in 1926 in the village of Killeigh, County Offaly, Ireland at Millbrook House(only 5 miles from Tullamore), the home of parish curate, Fr Martin Brophy. When he was born Mick was the runt of the litter but Michael Greene, who worked for Fr Brophy, singled the little pup out as a future champion and insisted that he be allowed to rear him. With constant attention and regular exercise Mick The Miller developed into a racing machine. His first forays were on local coursing fields where he had some success but he showed his real talent on the track where he won 15 of his first 20 races.

.jpg)

In 1929 Fr Brophy decided to try Mick in English Greyhound Derby at White City, London. On his first trial-run, Mick equalled the track record. Then, in his first heat, he broke the world record, becoming the first greyhound ever to run 525 yards in under 30 seconds. Fr Brophy was inundated with offers and sold him to Albert Williams. Mick went on to win the 1929 Derby. Within a year he had changed hands again to Arundel H Kempton and won the Derby for a second time.

Over the course of his English career he won 36 of his 48 races, including the Derby (twice), the St Leger, the Cesarewitch, and the Welsh Derby. He set six new world records and two new track records. He was the first greyhound to win 19 races in a row. Several of his records went unbroken for over 40 years. He won, in total, almost £10,000 in prizemoney. But he also became the poster-dog for greyhound racing. He was a celebrity on a par with any sports person, muscisian or moviestar. The more famous he became, the more he attracted people to greyhound racing. Thousands thronged to watch him, providing a huge boost to the sport. It is said that he actually saved the sport of greyhound racing.

After retirement to stud his popularity continued. He starred in the film Wild Boy (based on his life-story) in 1934 which was shown in cinemas all across the UK. He was in huge demand on the celebrity circuit, opening shops, attending big races and even rubbing shoulder with royalty (such as the King and Queen) at charity events. When he died in 1939 aged 12, his owner donated his body to the British Natural History Museum in London. And Mick`s fame has continued ever since. In 1981 he was inducted into the American Hall of Fame (International Section). In 1990 English author Michael Tanner published a book, Mick The Miller - Sporting Icon Of the Depression. And in 2011 the people of Killeigh erected a monument on the village green to honour their most famous son. Mick The Miller is not just the most famous greyhound of all time but one of the most loved dogs that has ever lived.

-

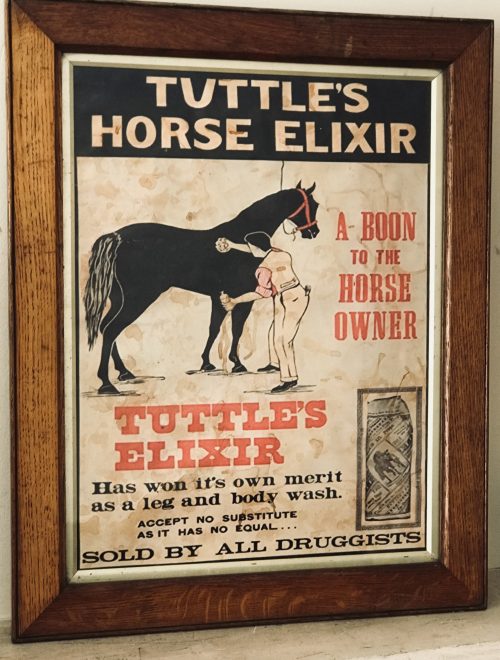

Tuttle's Horse Elixir -A boon for the Horse Owner ! Kilcullen Co Kildare. 62cm x 47cm Very rare and well framed Tuttle's Horse Elixir poster. The poster was published by Buck Printing Company located in Boston around 1885. The poster is marked "Tuttle's Horse Elixir - A Boon to the Horse Owner - Tuttle's Elixir Has won it's own merit as a leg and body wash. Accept no substitute as it has no equal... Sold By Druggists". It also shows an image of a man taking care of a horse. here was two companies running with similar names Tuttle's Elexer out of NY and Tuttle's Elixir Co. out of 19 Beverly St. Boston Mass. HISTORY OF TUTTLE’S ELEXER: Over a hundred years ago a veterinary surgeon named Dr.S.A. TUTTLE put together natural ingredients in the proper proportion to produce a unique liniment that is just as effective today as it was back in 1872. Dr. Tuttle began with denatured grain alcohol and gum turpentine. These are the solvents that carry the other active ingredients. Two essential oils, camphor and oil of hemlock, were added for their counterirritant and rubifacient effects. This stimulation of the skin and circulatory system generates natural warmth and delivery of the healing components of the blood.To enhance the effectiveness of these agents, Dr.Tuttle added ox gall, an ingredient with specific types of activity found exclusively in Tuttle’s ELEXER. Ox Gall is a unique ingredient that contains sodium salts of glycocholic and taurocholic acids and lecithin as key components.Glycocholic acid and taurocholic acids are powerful biological detergents that act to solubilize fats, and lecithin is a naturally occurring compound that acts as an emulsifier, stabilizer, antioxidant, lubricant and dispersant. This combination with the alcohol and other ingredients in Tuttle’s ELEXER makes it an excellent emulsifier of oil, grease and dirt for cleansing the affected area, particularly when mixed into a water solution. Tuttle’s ELEXER has been used by horse trainers in the U.S. since 1872. Manufactured from Dr. S.A. Tuttle’s original formula, there is no other preparation like it.

Tuttle's Horse Elixir -A boon for the Horse Owner ! Kilcullen Co Kildare. 62cm x 47cm Very rare and well framed Tuttle's Horse Elixir poster. The poster was published by Buck Printing Company located in Boston around 1885. The poster is marked "Tuttle's Horse Elixir - A Boon to the Horse Owner - Tuttle's Elixir Has won it's own merit as a leg and body wash. Accept no substitute as it has no equal... Sold By Druggists". It also shows an image of a man taking care of a horse. here was two companies running with similar names Tuttle's Elexer out of NY and Tuttle's Elixir Co. out of 19 Beverly St. Boston Mass. HISTORY OF TUTTLE’S ELEXER: Over a hundred years ago a veterinary surgeon named Dr.S.A. TUTTLE put together natural ingredients in the proper proportion to produce a unique liniment that is just as effective today as it was back in 1872. Dr. Tuttle began with denatured grain alcohol and gum turpentine. These are the solvents that carry the other active ingredients. Two essential oils, camphor and oil of hemlock, were added for their counterirritant and rubifacient effects. This stimulation of the skin and circulatory system generates natural warmth and delivery of the healing components of the blood.To enhance the effectiveness of these agents, Dr.Tuttle added ox gall, an ingredient with specific types of activity found exclusively in Tuttle’s ELEXER. Ox Gall is a unique ingredient that contains sodium salts of glycocholic and taurocholic acids and lecithin as key components.Glycocholic acid and taurocholic acids are powerful biological detergents that act to solubilize fats, and lecithin is a naturally occurring compound that acts as an emulsifier, stabilizer, antioxidant, lubricant and dispersant. This combination with the alcohol and other ingredients in Tuttle’s ELEXER makes it an excellent emulsifier of oil, grease and dirt for cleansing the affected area, particularly when mixed into a water solution. Tuttle’s ELEXER has been used by horse trainers in the U.S. since 1872. Manufactured from Dr. S.A. Tuttle’s original formula, there is no other preparation like it. -

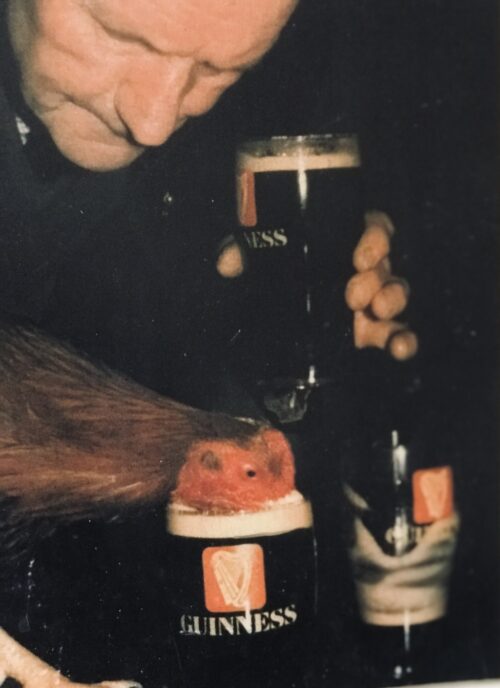

Brilliant photograph from 1960 as proud owner/trainer Denis Hyland lovingly buys a second pint of Guinness for his undefeated 3 time Heavyweight Cockfighting Champion of Ireland -Ginger.For more information on the ancient sport of cockfighting please read on . 50cm x40cm Stradbally Co Laois Nowadays Gaelic Games, soccer and rugby lead the way. But there used to be a time when cockfighting was the most popular spectator "sport" in Ireland.Naturally the gruesome nature of the activity means it is illegal today in most parts of the world.UCD professor Paul Rouse has shared the history of many Irish sports, and this week cockfighting was under the microscope. "From the Middle Ages onwards, from 1200 to 1300 onwards, there is evidence of cockfighting taking place [in Ireland] and actually not just evidence of it taking place but the simple fact that it was central to Irish life," he said. Indeed it was so central to life that for example, shortly after 1798 in the market of Kildare Town, a cockpit was build to stage fights. "And that is a unique thing. We know that there were cockfighting pits all across Ireland," Rouse adds. "All across the place you have evidence of cockfighting. And they're only the ones that were dedicated purpose-built cockpits. We know that there was cockfighting in pubs, theatres, on streets, in sheds, in back lanes, out in fields. It was everywhere."Rouse also explained that cockfighting transcended class and social divisions, also adding that bull-baiting and bear-baiting were also popular in the United Kingdom in previous centuries with only a few detractors. An RTE report from 1967 further investigated this clandestine sport, roughly around the same era that Ginger was ruling the roost (so to speak!)

Brilliant photograph from 1960 as proud owner/trainer Denis Hyland lovingly buys a second pint of Guinness for his undefeated 3 time Heavyweight Cockfighting Champion of Ireland -Ginger.For more information on the ancient sport of cockfighting please read on . 50cm x40cm Stradbally Co Laois Nowadays Gaelic Games, soccer and rugby lead the way. But there used to be a time when cockfighting was the most popular spectator "sport" in Ireland.Naturally the gruesome nature of the activity means it is illegal today in most parts of the world.UCD professor Paul Rouse has shared the history of many Irish sports, and this week cockfighting was under the microscope. "From the Middle Ages onwards, from 1200 to 1300 onwards, there is evidence of cockfighting taking place [in Ireland] and actually not just evidence of it taking place but the simple fact that it was central to Irish life," he said. Indeed it was so central to life that for example, shortly after 1798 in the market of Kildare Town, a cockpit was build to stage fights. "And that is a unique thing. We know that there were cockfighting pits all across Ireland," Rouse adds. "All across the place you have evidence of cockfighting. And they're only the ones that were dedicated purpose-built cockpits. We know that there was cockfighting in pubs, theatres, on streets, in sheds, in back lanes, out in fields. It was everywhere."Rouse also explained that cockfighting transcended class and social divisions, also adding that bull-baiting and bear-baiting were also popular in the United Kingdom in previous centuries with only a few detractors. An RTE report from 1967 further investigated this clandestine sport, roughly around the same era that Ginger was ruling the roost (so to speak!)Cockfighting is an illegal sport, it is still practised in Ireland, and shows no signs of dying out.

A cockfight is a blood sport where two cockerels are placed in a ring, called a ‘pit’, and fight one another, often until the death, for the entertainment of onlookers. Gambling also takes place at these events. Cathal O’Shannon talks to a man identified as Charlie, who trains cockerels, attends cockfights and also acts as an adjudicator at cockfighting matches. Charlie explains what happens at a cockfight, or ‘main’. The birds are placed in the pit and advance on one another. Men pick the birds up, or ‘haunt the cocks’, when one of the cockerels is injured, or when he goes outside the pit, and go back to their station again. The adjudicator then starts counting to 30. This gives the birds a brief rest before the next bout commences. When asked if he thinks that the metal spurs tied to the cockerels’ feet are cruel, he says "A cock can run if he likes...he can quit fighting." Contrary to popular opinion, Charlie does not believe the sport is a cruel one, as he loves the birds, and looks after them in the best way possible prior to a fight, "Get him cleaned up, and give him the sweet milk and the porridge, and get him dosed up again, a wee taste of rice, you get him closed...you put him on the bread then...give him three feeds...bread, and the whites of eggs, and spiced port wine or sherry." When there is a ‘main’ on, the news is spread by word of mouth, often less than 24 hours in advance. Cathal O’Shannon notes that the best place to find a cockfight is, ironically, often where there is a large police presence, such as a football match, a parade, or a Fleadh Cheoil. Any place where the police are too busy to notice. This report for Newsbeat was broadcast on 19 May 1967. The reporter was Cathal O’Shannon. ‘Newsbeat’ was a half-hour feature programme presented by Frank Hall and ran for 7 years from September 1964 to June 1971. ‘Newsbeat’ went out from Monday to Friday on RTE television and reported on current affairs and issues of local interest from around Ireland. The final programme was broadcast on the 11 June 1971. Origins : Co Laois Dimensions :60cm x 50cm 6kg -

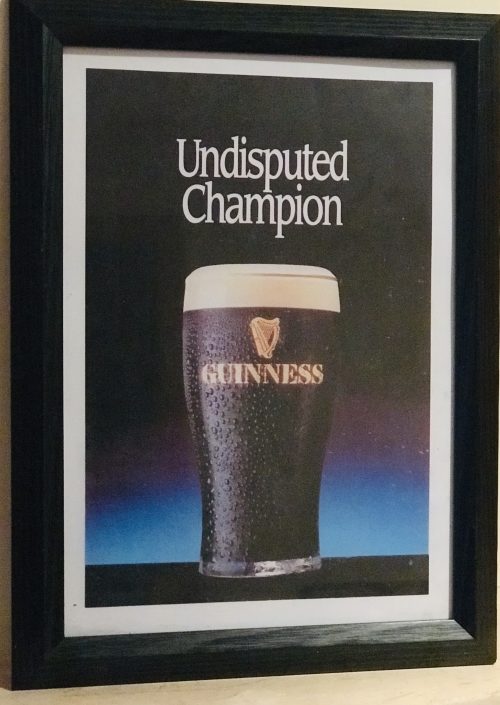

Undisputed Champion advert from the Guinness archives portraying the majesty of a perfectly poured pint of Guinness. Dimensions : 35cm x 48cm Glazed Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm

Undisputed Champion advert from the Guinness archives portraying the majesty of a perfectly poured pint of Guinness. Dimensions : 35cm x 48cm Glazed Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm -

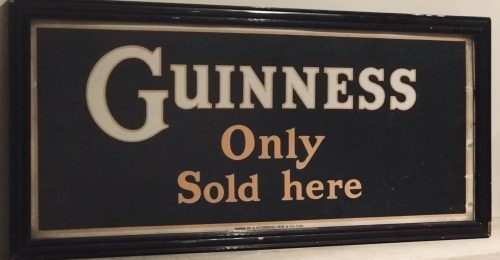

Very unusual Guinness-Only sold here Advert from the 1960s.Issued by A.Guinness,Son & Co.Ltd. 31cm x 66cm Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain. Arthur Guinness started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.

Very unusual Guinness-Only sold here Advert from the 1960s.Issued by A.Guinness,Son & Co.Ltd. 31cm x 66cm Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain. Arthur Guinness started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks. -

Superb vintage WW1 recruitment poster imploring the young men of Ireland to join the British Army.The poster depicts a lone piper with the famous mascot of the Royal Irish Regiment ,an Irish Wolfhound. 47cm x 38cm Nenagh Co TipperaryThe British Army was a volunteer force when war broke out in 1914, and within weeks thousands of Irishmen had signed up to serve 'King and Country'. Ireland had a strong military tradition in the British armed forces, dating back to at least the early 1500s, and when war was declared on August 4, 1914, there were some 20,000 Irishmen already serving from a total army strength of some 247,000. In addition, there were another 30,000 in the first-line reserve, from a total of 145,000. But more were quickly needed. Secretary for War Lord Kitchener told the British cabinet that it would be a three-year conflict requiring at least one million men, meaning a recruitment drive was immediately undertaken. Posters quickly appeared across the country, focused on attracting men from all background Some appealed to a sense of duty and honour, but appeared to be aimed at British-born nationals rather than Irishmen.

Superb vintage WW1 recruitment poster imploring the young men of Ireland to join the British Army.The poster depicts a lone piper with the famous mascot of the Royal Irish Regiment ,an Irish Wolfhound. 47cm x 38cm Nenagh Co TipperaryThe British Army was a volunteer force when war broke out in 1914, and within weeks thousands of Irishmen had signed up to serve 'King and Country'. Ireland had a strong military tradition in the British armed forces, dating back to at least the early 1500s, and when war was declared on August 4, 1914, there were some 20,000 Irishmen already serving from a total army strength of some 247,000. In addition, there were another 30,000 in the first-line reserve, from a total of 145,000. But more were quickly needed. Secretary for War Lord Kitchener told the British cabinet that it would be a three-year conflict requiring at least one million men, meaning a recruitment drive was immediately undertaken. Posters quickly appeared across the country, focused on attracting men from all background Some appealed to a sense of duty and honour, but appeared to be aimed at British-born nationals rather than Irishmen. -

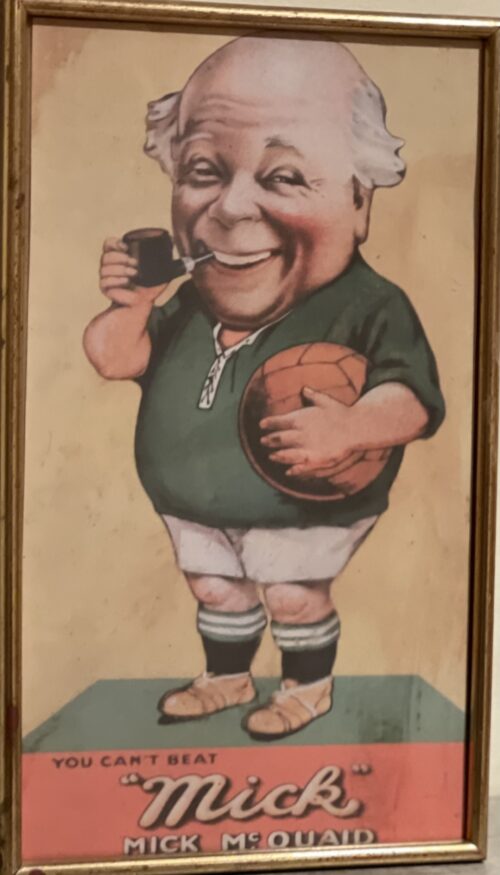

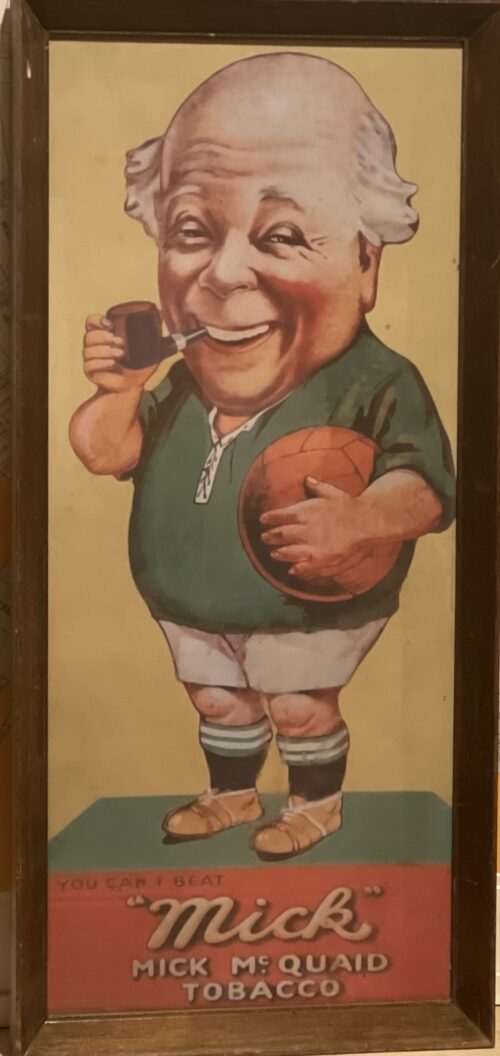

40cm x 24cm A very popular Pipe Tobacco from the P.Carrolls Tobacco Company in Dundalk Co Louth was Mick McQuaids.But who was this legendary, smiling character the product was inspired by ??? The tales of Mick McQuaid were first written by William Francis Lynam – a soldier, writer and editor who was born in Galway in 1833 and died in Dublin in 1894. Little is known about his background (or his military career), but by the 1860s he was living in Dublin and was – it appears – the owner and editor of the Shamrock story paper. One of the earliest Irish story papers, it was established in 1866 as a penny weekly ‘companion’ paper to the Irishman newspaper. The Irishman, a very advanced nationalist paper, was established in 1859 by Richard Pigott – a very colourful character in Irish journalism who would acquire infamy as the forger of the damning letters supposedly written by Parnell in the 1880s. The exact editorial and proprietorial relationship between the Irishman and the Shamrock is rather murky – some sources imply Pigott owned them both, while others insist that Lynam owned the Shamrock, in which case the precise nature of their connection is unknown. Pigott and Lynam may have been actual business partners, or simply had an informal alliance. The 1860s was of course the era of the Fenian movement in Ireland and abroad, and under Pigott’s editorship the Irishmanwas a very popular voice for Fenianism. If the Irishman was aimed at an adult readership seeking radical political news and commentary, the Shamrock was its more entertaining younger sibling, intended to instil a sense of national pride and identity in its boy (and occasional girl) readers. To do this, it specialised in exciting Irish historical fiction serials, set at key moments of Irish nationalist history such as the 1798 Rebellion or the Jacobite Wars, and usually centred around an ordinary Irish boy who readers could identify with as he became swept into political and military excitements and encountered historical figures such as Wolfe Tone or Redmond O’Hanlon. But as well as historical fiction, the Shamrock also published romances and vernacular tales of Irish life. The most successful of these vernacular tales were, by a very long way, the Mick McQuaid stories. A series of comic tales (although to be quite honest the modern reader might take some convincing of that description) set in what was then contemporary Ireland, they all featured the adventures of central character Mick McQuaid – a quick-thinking, wise-cracking chancer who nevertheless usually managed to save the day and prevent the more straight-forward villainy of figures such as agents for absentee landlords, or local gombeen men. Each story saw Mick in a new role and setting, such as ‘Mick McQuaid, Money Lender’, ‘Mick McQuaid, Member of Parliament’, ‘Mick McQuaid, Detective’, and ‘Mick McQuaid, Evangelist’. Each story was long, with (overly) complex plots, many characters, comic tangents and multiple narrative threads to be resolved, so they were serialised in short instalments over several months of weekly issues. These kind of serial stories were crucial to story papers, designed to bring readers back week after week and build a loyal and regular readership, and the Mick McQuaid stories were a classic example of their type. It has to be admitted it would be difficult to that claim the stories deserve to be ‘rediscovered’ by modern readers. They are an interesting window into popular fiction of the era, especially in terms of their representations of Irish life and society – however their plots are unwieldy, their humour has not aged well and they are written in an almost impenetrable ‘Irish’ dialect which was obviously part of their appeal in the 1860s but which is extremely difficult to read now. Instead what is most interesting about the Mick McQuaid stories is their extraordinary popularity across many decades. Lynam reportedly became bored with the stories after just a few years, and indeed replaced them with tales of another very similar ‘charming Irish rogue’ anti-hero, the Darby Durkan series, which in their turn were also fairly popular. But popular demand for continued Mick McQuaid stories forced him to write more of them (a common experience for authors of popular fiction, most famously in the case of Conan Doyle’s reluctant resurrection of Sherlock Holmes). Indeed, the circulation of the Shamrock reportedly dropped sharply when he attempted to end the McQuaid stories, so they had to be revived and reprinted. It is difficult to be sure exactly how many stories there are in total (perhaps ten or so), each one lasting up to 6 months of weekly instalments – but for a youthful audience this was enough to keep printing and reprinting them over years and eventually decades. Rather like the endlessly circulating repeats of television sit-coms in our own era, which happily rewatched by fans and watched for the first time by successive generations (Faulty Towers being the obvious example, with just twelve episodes ever made in the 1970s, but which are still being screened 40 years later) these very popular serials played on an endless loop in the story papers. Lynam died in 1894, but his serials lived on without him. The Darby Durkan stories appeared in the Shamrock’s rival story paper the Emerald in the early 20thC, and after the two papers merged in 1912 the McQuaid stories also continued in the new paper until its demise in 1919 – and may well have continued to appear in other publications after that although I have yet to find them. Their popularity was such that in 1889 Carroll’s Tobacco company in Dundalk named a new brand of pipe tobacco after Mick McQuaid, who often smoked a pipe in the stories as he held forth with his distinctive folk wisdom. The brand was itself a great success (presumably the tobacco and the stories amplified each other’s standing among readers and smokers in ways that benefitted both), and by the 1920s Carroll’s had commissioned a cartoon version of Mick McQuaid for their packaging and advertising – the photograph accompanying this post is of a tobacco tin from the mid-20thC. So while the stories had not had significant illustrations during their 19thC hey-day, the Mick McQuaid character took visual form years after his author’s death, and in fact became one of mid-20thC Ireland’s most successful brands, only being discontinued in 2016 – a strange afterlife for a fictional character first invented in 1867.