-

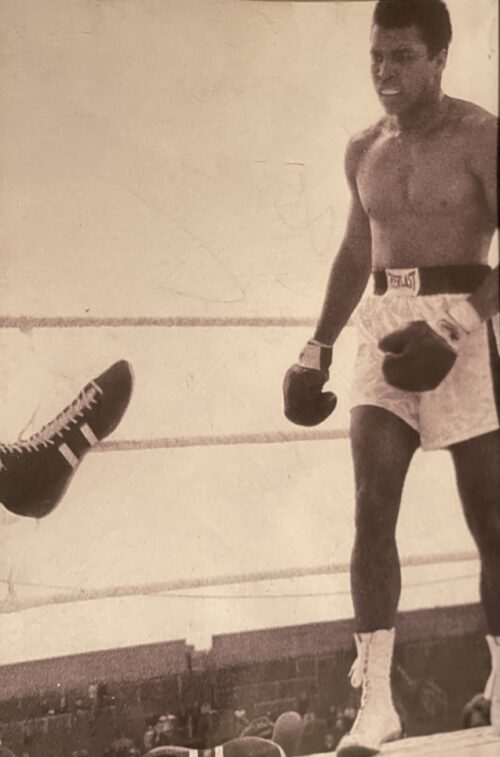

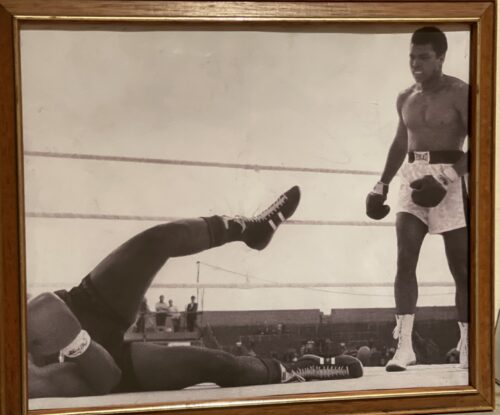

40cm x 34cm July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.

40cm x 34cm July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history. -

62cm x 62cm approx A real rarity here in the octagonal shape of a vintage Ireland Inland Waterways Cast-iron Sign denoting the river Shannon & Limerick.This most unusual find has been carefully restored and repainted and will make a most suitable exhibit for the most discerning Irish bar with Limerick /River Shannon affiliations.Please contact us directly at irishpubemporium@gmail.com or at 00353 878393200 to discuss.

62cm x 62cm approx A real rarity here in the octagonal shape of a vintage Ireland Inland Waterways Cast-iron Sign denoting the river Shannon & Limerick.This most unusual find has been carefully restored and repainted and will make a most suitable exhibit for the most discerning Irish bar with Limerick /River Shannon affiliations.Please contact us directly at irishpubemporium@gmail.com or at 00353 878393200 to discuss. -

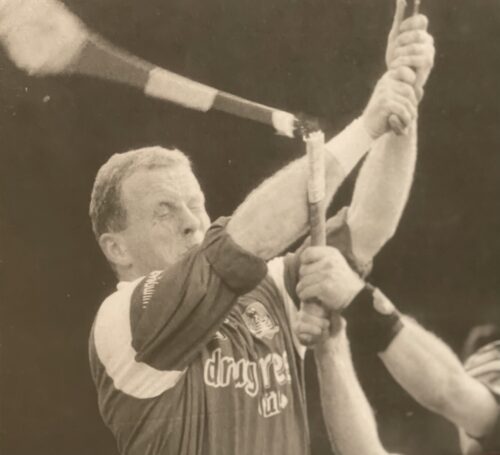

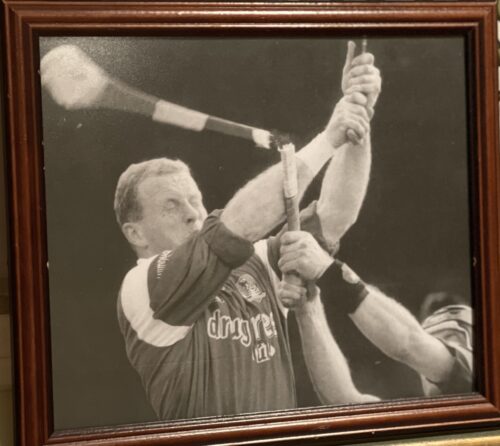

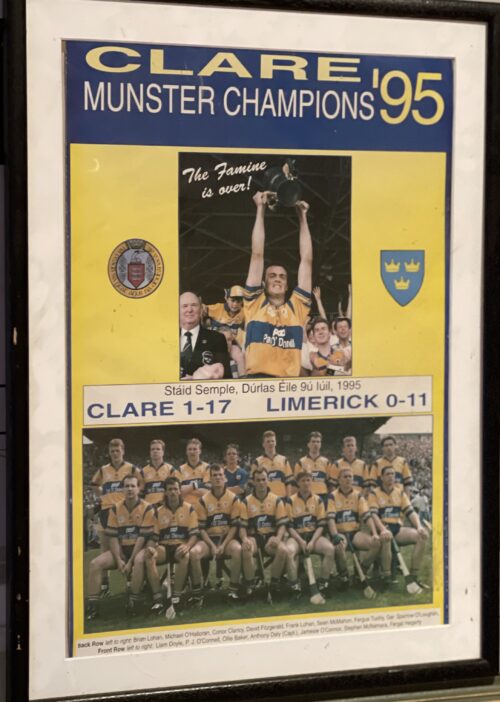

48cm x 35cm

48cm x 35cmIt was Richie Connor in the early 1990s who first introduced me to the concept. For the Offaly team he captained, ultimately to the 1982 All-Ireland, beating Dublin in the 1980 Leinster final had he said been their most significant achievement.

This was because winning the province represented a longer journey from where the team under Eugene McGee had started than the distance from there to the Sam Maguire.

Maybe the reasoning was slightly different in Clare but it amounted to the same thing. In the few weeks that shimmered in the radiant summer of 1995 between winning Munster and the All-Ireland semi-final against Galway, manager Ger Loughnane was certainly of that view.

“In Clare, Munster is the Mount Everest. All along Munster was what was talked about. I remember stopping Nenagh on the way back from the League final and a man saying, ‘if only we could win Munster once, it would make up for everything’.

“The reaction to our winning Munster has been far greater than what would happen in other counties if they won an All-Ireland.”

Clare had got to the stage where they were being upstaged by their footballers whose first Munster title since 1917 had been sensationally won in 1992 leaving the hurlers by-passed.

Anthony Daly, prominent in 1995 as the exuberant captain of the hurlers, remembered the big-ball community’s notions. He went to support the footballers in their All-Ireland semi-final against Dublin three years previously. In a bar beforehand he was mocked for band-wagoning.

“Do you go to our matches at all,” asks Daly.

“I do, I do,” comes the response.

“And when you do, does anyone ever tell you to f*** off back to west Clare?”

Boom, boom.

Climbed Everest

Twenty-five years ago today (Thursday) the county hurlers climbed Everest and in unexpected style. Clare had qualified for a third successive Munster final but the previous two, against Limerick and Tipperary had ended in heavy defeats.

This season would be different. Loughnane’s elevation from selector to manager crystallised the potential that his predecessor Len Gaynor had harnessed to reach Munster finals in 1993 and ‘94. They had taken the lessons of losing to a Zen level.

I remember seeing Loughnane and his selectors Mike McNamara and Tony Considine sitting in the Queens Hotel in Ennis after a league match with a fairly full-strength Tipperary.

Clare’s James O’Connor is challenged by Limerick’s Gary Kirby during the 1995 Munster final. Photograph: Tom Honan/Inpho They were super-pleased with the win, one of a number of markers laid down in a season that ended with defeat in the final against Kilkenny after which the manager famously declared that they would win Munster. The approach had been clear: find some new players, get incredibly fit and start beating likely rivals.

The winter had been a time of slog under McNamara’s fundamentalist training but the late spring with its brightening nights would be a time for sharpening the hurling and adding speed to their playbook.

“In a way the League final was the best thing that happened us,” said Loughnane after the provincial success. “All the old failings were there. We were too tense: all frenzy, no method. We were going to have to use our heads. If we’d won the League we definitely wouldn’t have won the Munster championship.”

Limerick were in a valley season between two demoralising All-Ireland final defeats but were raging favourites, having beaten Tipperary while Clare had laboured to get past Cork.

Clare also had their past, 11 Munster final defeats since the previous win in 1932 and well beaten by Limerick the previous year. The League final defeat a mere two months previously didn’t help the argument that the team had the ability to win big matches.

As a match it doesn’t look great these days. There are too many errors and too much imprecision in the play. Limerick look lethargic and off-key. They play the first half with the advantage of a strong wind but trail at half-time.

In a low-scoring, scrappy affair Clare aren’t doing themselves justice either but for a team,who had been trimmed in their previous finals they’re hanging in there for most of the first half. In other words the match isn’t getting away from them, either - which is an improvement on the recent past.

Davy Fitzgerald

Goalkeeper Davy Fitzgerald’s expertly hit penalty edges Clare in front and tactically they have taken a grip. Fitzgerald is also excellent in goal producing a couple of saves that prevent Limerick from getting too involved.

Ollie Baker, of whom a lot had been expected when he was drafted into the team for the league, has a non-stop match, physically overshadowing the powerful Limerick pairing of Mike Houlihan and Seán O’Neill and beside him James O’Connor overcomes a difficult start and is on to everything, fast and fluent.

His six points include four from play and his only failure of marksmanship is a shot that hits the post late in the match. PJ O’Connell also gets four from play but is selected as MOTM for the job done on disorientating Ciarán Carey with his constant movement.

Clare captain Anthony Daly with the trophy after his side’s 1995 Munster final win over Limerick. Tom Honan/Inpho “I knew I had to keep Ciarán Carey away from the puck-outs,” he says afterwards, “so I kept him running around. I had done a lot of work for this and I knew I would not get winded or caught for pace. I just kept running him and I could see it was having an effect.”

Seán McMahon broke his collarbone in the semi-final against Cork and returns for the final a week earlier than ideal but thrives as Gary Kirby, who had destroyed him a year previously, falters.

Clare’s grip tightens. Limerick manage just four points in the second half, as the winners pull away steadily.

Stunning win

It’s a stunning win - a tribute to Loughnane, who in the years before the acid erosion of controversies and fallings-out is a charismatic leader, whose prescriptions were single-mindedly adopted by the players and embraced by the Clare public.

“The feeling was that at long last a barrier had been broken,” he said before the All-Ireland semi-final. “The atmosphere in the county was incredible. It was great for the footballers a couple of years ago but they hadn’t been waiting and failing the way the hurlers had for years and years and years. It was very emotional, more because it was so unexpected after Limerick trouncing Clare last year. A good few didn’t even go to Thurles because they were afraid.”

Clare captain Anthony Daly at the county’s homecoming in 1995. Photograph: Inpho For those few weeks, they are on the cusp of history, something almost spiritual. In the week before the Galway semi-final, Loughnane recounted how he had happened upon a car accident.

He hurries to check on the elderly motorist, who is shaken but not injured. They are joined by a third man.

“This other fella is looking at me and says, ‘Ger, isn’t it?’ I said, ‘yes’ and he says to the poor old man: ‘It’s Ger Loughnane! Isn’t that enough to make you better?’”

A nurse arrives with the ambulance and pauses to comment.

“I hope everything’s right for Sunday.”

Need she have asked in that summer of summers?

-

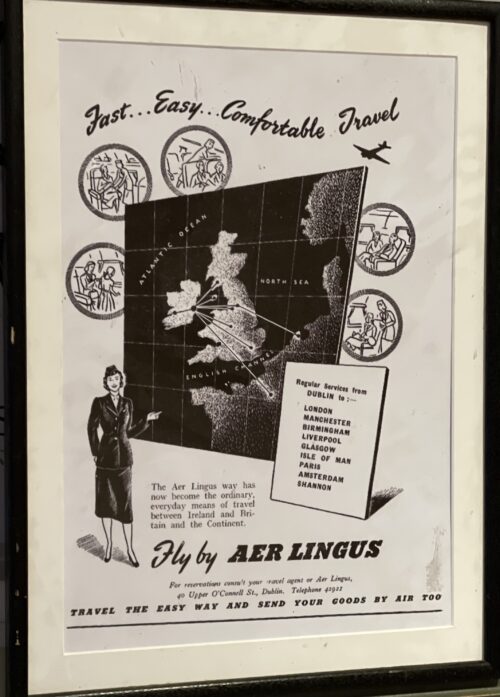

48cm x 35cm Aer Lingus was founded on 15 April 1936, with a capital of £100,000. Its first chairman was Seán Ó hUadhaigh.Pending legislation for Government investment through a parent company, Aer Lingus was associated with Blackpool and West Coast Air Services which advanced the money for the first aircraft, and operated with Aer Lingus under the common title "Irish Sea Airways". Aer Lingus Teoranta was registered as an airline on 22 May 1936.The name Aer Lingus was proposed by Richard F O'Connor, who was County Cork Surveyor, as well as an aviation enthusiast. On 27 May 1936, five days after being registered as an airline, its first service began between Baldonnel Airfield in Dublin and Bristol (Whitchurch) Airport, the United Kingdom, using a six-seater de Havilland DH.84 Dragon biplane (registration EI-ABI), named Iolar (Eagle). Later that year, the airline acquired its second aircraft, a four-engined biplane de Havilland DH.86 Express named "Éire", with a capacity of 14 passengers. This aircraft provided the first air link between Dublin and London by extending the Bristol service to Croydon. At the same time, the DH.84 Dragon was used to inaugurate an Aer Lingus service on the Dublin-Liverpool route. The airline was established as the national carrier under the Air Navigation and Transport Act (1936). In 1937, the Irish government created Aer Rianta (now called Dublin Airport Authority), a company to assume financial responsibility for the new airline and the entire country's civil aviation infrastructure. In April 1937, Aer Lingus became wholly owned by the Irish government via Aer Rianta. The airline's first General Manager was Dr J.F. (Jeremiah known as 'Jerry') Dempsey, a chartered accountant, who joined the company on secondment from Kennedy Crowley & Co (predecessor to KPMG as Company Secretary in 1936 (aged 30) and was appointed to the role of General Manager in 1937. He retired 30 years later in 1967 at the age of 60. In 1938, a de Havilland DH.89 Dragon Rapide replaced Iolar, and the company purchased a second DH.86B. Two Lockheed 14s arrived in 1939, Aer Lingus' first all-metal aircraft.In January 1940, a new airport opened in the Dublin suburb of Collinstown and Aer Lingus moved its operations there. It purchased a new DC-3 and inaugurated new services to Liverpool and an internal service to Shannon. The airline's services were curtailed during World War II with the sole route being to Liverpool or Barton Aerodrome Manchester depending on the fluctuating security situation.

48cm x 35cm Aer Lingus was founded on 15 April 1936, with a capital of £100,000. Its first chairman was Seán Ó hUadhaigh.Pending legislation for Government investment through a parent company, Aer Lingus was associated with Blackpool and West Coast Air Services which advanced the money for the first aircraft, and operated with Aer Lingus under the common title "Irish Sea Airways". Aer Lingus Teoranta was registered as an airline on 22 May 1936.The name Aer Lingus was proposed by Richard F O'Connor, who was County Cork Surveyor, as well as an aviation enthusiast. On 27 May 1936, five days after being registered as an airline, its first service began between Baldonnel Airfield in Dublin and Bristol (Whitchurch) Airport, the United Kingdom, using a six-seater de Havilland DH.84 Dragon biplane (registration EI-ABI), named Iolar (Eagle). Later that year, the airline acquired its second aircraft, a four-engined biplane de Havilland DH.86 Express named "Éire", with a capacity of 14 passengers. This aircraft provided the first air link between Dublin and London by extending the Bristol service to Croydon. At the same time, the DH.84 Dragon was used to inaugurate an Aer Lingus service on the Dublin-Liverpool route. The airline was established as the national carrier under the Air Navigation and Transport Act (1936). In 1937, the Irish government created Aer Rianta (now called Dublin Airport Authority), a company to assume financial responsibility for the new airline and the entire country's civil aviation infrastructure. In April 1937, Aer Lingus became wholly owned by the Irish government via Aer Rianta. The airline's first General Manager was Dr J.F. (Jeremiah known as 'Jerry') Dempsey, a chartered accountant, who joined the company on secondment from Kennedy Crowley & Co (predecessor to KPMG as Company Secretary in 1936 (aged 30) and was appointed to the role of General Manager in 1937. He retired 30 years later in 1967 at the age of 60. In 1938, a de Havilland DH.89 Dragon Rapide replaced Iolar, and the company purchased a second DH.86B. Two Lockheed 14s arrived in 1939, Aer Lingus' first all-metal aircraft.In January 1940, a new airport opened in the Dublin suburb of Collinstown and Aer Lingus moved its operations there. It purchased a new DC-3 and inaugurated new services to Liverpool and an internal service to Shannon. The airline's services were curtailed during World War II with the sole route being to Liverpool or Barton Aerodrome Manchester depending on the fluctuating security situation. An Aer Lingus Douglas DC-3 at Manchester Airport in 1948 wearing the first postwar livery.

An Aer Lingus Douglas DC-3 at Manchester Airport in 1948 wearing the first postwar livery.Post-war expansion

On 9 November 1945, regular services were resumed with an inaugural flight to London. From this point Aer Lingus aircraft, initially mostly Douglas DC-3s, were painted in a silver and green livery. The airline introduced its first flight attendants. In 1946, a new Anglo-Irish agreement gave Aer Lingus exclusive UK traffic rights from Ireland in exchange for a 40% holding by British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) and British European Airways (BEA). Because of Aer Lingus' growth the airline bought seven new Vickers Viking aircraft in 1947, however, these proved to be uneconomical and were soon sold.In 1947, Aerlínte Éireann came into existence to operate transatlantic flights to New York City from Ireland. The airline ordered five new Lockheed L-749 Constellations, but a change of government and a financial crisis prevented the service from starting. John A Costello, the incoming Fine Gael Taoiseach (Prime Minister), was not a keen supporter of air travel and thought that flying the Atlantic was too grandiose a scheme for a small airline from a small country like Ireland. A Bristol 170 Freighter at Manchester Airport in 1953.During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Aer Lingus introduced routes to Brussels, Amsterdam via Manchester and to Rome. Because of the expanding route structure, the airline became one of the early purchasers of Vickers Viscount 700s in 1951, which were placed in service in April 1954. In 1952, the airline expanded its all-freight services and acquired a small fleet of Bristol 170 Freighters, which remained in service until 1957. Prof. Patrick Lynch was appointed the chairman of Aer Lingus and Aer Rianta in 1954 and served in the position until 1975. In 1956, Aer Lingus introduced a new, green-top livery with a white lightning flash down the windows and the Irish flag displayed on the fin.

A Bristol 170 Freighter at Manchester Airport in 1953.During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Aer Lingus introduced routes to Brussels, Amsterdam via Manchester and to Rome. Because of the expanding route structure, the airline became one of the early purchasers of Vickers Viscount 700s in 1951, which were placed in service in April 1954. In 1952, the airline expanded its all-freight services and acquired a small fleet of Bristol 170 Freighters, which remained in service until 1957. Prof. Patrick Lynch was appointed the chairman of Aer Lingus and Aer Rianta in 1954 and served in the position until 1975. In 1956, Aer Lingus introduced a new, green-top livery with a white lightning flash down the windows and the Irish flag displayed on the fin. A Vickers Viscount 808 in "green top" livery at Manchester Airport in 1963.

A Vickers Viscount 808 in "green top" livery at Manchester Airport in 1963.First transatlantic service

On 28 April 1958, Aerlínte Éireann operated its first transatlantic service from Shannon to New York.In 1960, Aerlínte Éireann was renamed Aer Lingus. Aer Lingus bought seven Fokker F27 Friendships, which were delivered between November 1958 and May 1959. These were used in short-haul services to the UK, gradually replacing the Dakotas, until Aer Lingus replaced them in 1966 with secondhand Viscount 800s. The airline entered the jet age on 14 December 1960 when it received three Boeing 720 for use on the New York route and the newest Aer Lingus destination Boston. In 1963, Aer Lingus added Aviation Traders Carvairs to the fleet. These aircraft could transport five cars which were loaded into the fuselage through the nose of the aircraft. The Carvair proved to be uneconomical for the airline partly due to the rise of auto ferry services, and the aircraft were used for freight services until disposed of. The Boeing 720s proved to be a success for the airline on the transatlantic routes. To supplement these, Aer Lingus took delivery of its first larger Boeing 707 in 1964, and the type continued to serve the airline until 1986. A Boeing 720 in Aer Lingus-Irish International livery in 1965.

A Boeing 720 in Aer Lingus-Irish International livery in 1965.Jet aircraft

Conversion of the European fleet to jet equipment began in 1965 when the BAC One-Eleven started services on continental Europe.The airline adopted a new livery in the same year, with a large green shamrock on the fin. In 1966, the remainder of the company's shares held by Aer Rianta were transferred to the Minister for Finance. A Fokker F27 Friendship at Manchester Airport in 1965. The F27 was used on short-haul services between 1958 and 1966.In 1966, the company added routes to Montreal and Chicago. In 1968, flights from Belfast, in Northern Ireland, to New York City started, however, it was soon suspended due to the beginning of the Troubles.Aer Lingus introduced Boeing 737s to its fleet in 1969 to cope with the high demand for flights between Dublin and London. Later, Aer Lingus extended the 737 flights to all of its European networks. In 1967, after 30 years of service, General Manager Dr J.F. Dempsey signed the contract for the airline's first two Boeing 747 aircraft before he retired later that year.

A Fokker F27 Friendship at Manchester Airport in 1965. The F27 was used on short-haul services between 1958 and 1966.In 1966, the company added routes to Montreal and Chicago. In 1968, flights from Belfast, in Northern Ireland, to New York City started, however, it was soon suspended due to the beginning of the Troubles.Aer Lingus introduced Boeing 737s to its fleet in 1969 to cope with the high demand for flights between Dublin and London. Later, Aer Lingus extended the 737 flights to all of its European networks. In 1967, after 30 years of service, General Manager Dr J.F. Dempsey signed the contract for the airline's first two Boeing 747 aircraft before he retired later that year. An Aviation Traders Carvair that was used as a vehicle freighter is seen loading a car at Bristol Airport in 1964.

An Aviation Traders Carvair that was used as a vehicle freighter is seen loading a car at Bristol Airport in 1964. -

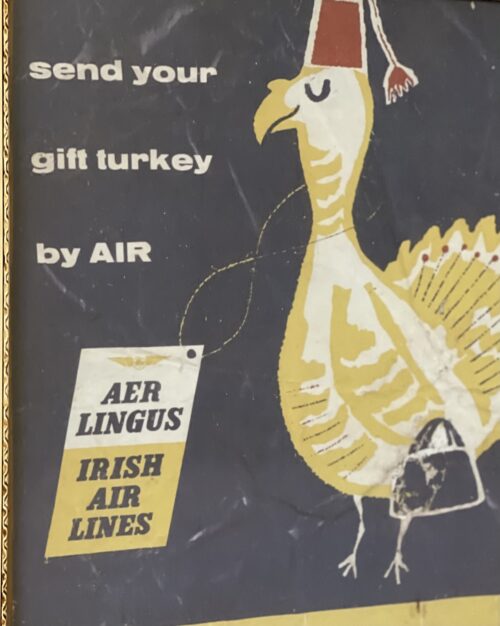

45cm x 34cm Aer Lingus was founded on 15 April 1936, with a capital of £100,000. Its first chairman was Seán Ó hUadhaigh.Pending legislation for Government investment through a parent company, Aer Lingus was associated with Blackpool and West Coast Air Services which advanced the money for the first aircraft, and operated with Aer Lingus under the common title "Irish Sea Airways". Aer Lingus Teoranta was registered as an airline on 22 May 1936.The name Aer Lingus was proposed by Richard F O'Connor, who was County Cork Surveyor, as well as an aviation enthusiast. On 27 May 1936, five days after being registered as an airline, its first service began between Baldonnel Airfield in Dublin and Bristol (Whitchurch) Airport, the United Kingdom, using a six-seater de Havilland DH.84 Dragon biplane (registration EI-ABI), named Iolar (Eagle). Later that year, the airline acquired its second aircraft, a four-engined biplane de Havilland DH.86 Express named "Éire", with a capacity of 14 passengers. This aircraft provided the first air link between Dublin and London by extending the Bristol service to Croydon. At the same time, the DH.84 Dragon was used to inaugurate an Aer Lingus service on the Dublin-Liverpool route. The airline was established as the national carrier under the Air Navigation and Transport Act (1936). In 1937, the Irish government created Aer Rianta (now called Dublin Airport Authority), a company to assume financial responsibility for the new airline and the entire country's civil aviation infrastructure. In April 1937, Aer Lingus became wholly owned by the Irish government via Aer Rianta. The airline's first General Manager was Dr J.F. (Jeremiah known as 'Jerry') Dempsey, a chartered accountant, who joined the company on secondment from Kennedy Crowley & Co (predecessor to KPMG as Company Secretary in 1936 (aged 30) and was appointed to the role of General Manager in 1937. He retired 30 years later in 1967 at the age of 60. In 1938, a de Havilland DH.89 Dragon Rapide replaced Iolar, and the company purchased a second DH.86B. Two Lockheed 14s arrived in 1939, Aer Lingus' first all-metal aircraft.In January 1940, a new airport opened in the Dublin suburb of Collinstown and Aer Lingus moved its operations there. It purchased a new DC-3 and inaugurated new services to Liverpool and an internal service to Shannon. The airline's services were curtailed during World War II with the sole route being to Liverpool or Barton Aerodrome Manchester depending on the fluctuating security situation.

45cm x 34cm Aer Lingus was founded on 15 April 1936, with a capital of £100,000. Its first chairman was Seán Ó hUadhaigh.Pending legislation for Government investment through a parent company, Aer Lingus was associated with Blackpool and West Coast Air Services which advanced the money for the first aircraft, and operated with Aer Lingus under the common title "Irish Sea Airways". Aer Lingus Teoranta was registered as an airline on 22 May 1936.The name Aer Lingus was proposed by Richard F O'Connor, who was County Cork Surveyor, as well as an aviation enthusiast. On 27 May 1936, five days after being registered as an airline, its first service began between Baldonnel Airfield in Dublin and Bristol (Whitchurch) Airport, the United Kingdom, using a six-seater de Havilland DH.84 Dragon biplane (registration EI-ABI), named Iolar (Eagle). Later that year, the airline acquired its second aircraft, a four-engined biplane de Havilland DH.86 Express named "Éire", with a capacity of 14 passengers. This aircraft provided the first air link between Dublin and London by extending the Bristol service to Croydon. At the same time, the DH.84 Dragon was used to inaugurate an Aer Lingus service on the Dublin-Liverpool route. The airline was established as the national carrier under the Air Navigation and Transport Act (1936). In 1937, the Irish government created Aer Rianta (now called Dublin Airport Authority), a company to assume financial responsibility for the new airline and the entire country's civil aviation infrastructure. In April 1937, Aer Lingus became wholly owned by the Irish government via Aer Rianta. The airline's first General Manager was Dr J.F. (Jeremiah known as 'Jerry') Dempsey, a chartered accountant, who joined the company on secondment from Kennedy Crowley & Co (predecessor to KPMG as Company Secretary in 1936 (aged 30) and was appointed to the role of General Manager in 1937. He retired 30 years later in 1967 at the age of 60. In 1938, a de Havilland DH.89 Dragon Rapide replaced Iolar, and the company purchased a second DH.86B. Two Lockheed 14s arrived in 1939, Aer Lingus' first all-metal aircraft.In January 1940, a new airport opened in the Dublin suburb of Collinstown and Aer Lingus moved its operations there. It purchased a new DC-3 and inaugurated new services to Liverpool and an internal service to Shannon. The airline's services were curtailed during World War II with the sole route being to Liverpool or Barton Aerodrome Manchester depending on the fluctuating security situation. An Aer Lingus Douglas DC-3 at Manchester Airport in 1948 wearing the first postwar livery.

An Aer Lingus Douglas DC-3 at Manchester Airport in 1948 wearing the first postwar livery.Post-war expansion

On 9 November 1945, regular services were resumed with an inaugural flight to London. From this point Aer Lingus aircraft, initially mostly Douglas DC-3s, were painted in a silver and green livery. The airline introduced its first flight attendants. In 1946, a new Anglo-Irish agreement gave Aer Lingus exclusive UK traffic rights from Ireland in exchange for a 40% holding by British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) and British European Airways (BEA). Because of Aer Lingus' growth the airline bought seven new Vickers Viking aircraft in 1947, however, these proved to be uneconomical and were soon sold.In 1947, Aerlínte Éireann came into existence to operate transatlantic flights to New York City from Ireland. The airline ordered five new Lockheed L-749 Constellations, but a change of government and a financial crisis prevented the service from starting. John A Costello, the incoming Fine Gael Taoiseach (Prime Minister), was not a keen supporter of air travel and thought that flying the Atlantic was too grandiose a scheme for a small airline from a small country like Ireland. A Bristol 170 Freighter at Manchester Airport in 1953.During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Aer Lingus introduced routes to Brussels, Amsterdam via Manchester and to Rome. Because of the expanding route structure, the airline became one of the early purchasers of Vickers Viscount 700s in 1951, which were placed in service in April 1954. In 1952, the airline expanded its all-freight services and acquired a small fleet of Bristol 170 Freighters, which remained in service until 1957. Prof. Patrick Lynch was appointed the chairman of Aer Lingus and Aer Rianta in 1954 and served in the position until 1975. In 1956, Aer Lingus introduced a new, green-top livery with a white lightning flash down the windows and the Irish flag displayed on the fin.

A Bristol 170 Freighter at Manchester Airport in 1953.During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Aer Lingus introduced routes to Brussels, Amsterdam via Manchester and to Rome. Because of the expanding route structure, the airline became one of the early purchasers of Vickers Viscount 700s in 1951, which were placed in service in April 1954. In 1952, the airline expanded its all-freight services and acquired a small fleet of Bristol 170 Freighters, which remained in service until 1957. Prof. Patrick Lynch was appointed the chairman of Aer Lingus and Aer Rianta in 1954 and served in the position until 1975. In 1956, Aer Lingus introduced a new, green-top livery with a white lightning flash down the windows and the Irish flag displayed on the fin. A Vickers Viscount 808 in "green top" livery at Manchester Airport in 1963.

A Vickers Viscount 808 in "green top" livery at Manchester Airport in 1963.First transatlantic service

On 28 April 1958, Aerlínte Éireann operated its first transatlantic service from Shannon to New York.In 1960, Aerlínte Éireann was renamed Aer Lingus. Aer Lingus bought seven Fokker F27 Friendships, which were delivered between November 1958 and May 1959. These were used in short-haul services to the UK, gradually replacing the Dakotas, until Aer Lingus replaced them in 1966 with secondhand Viscount 800s. The airline entered the jet age on 14 December 1960 when it received three Boeing 720 for use on the New York route and the newest Aer Lingus destination Boston. In 1963, Aer Lingus added Aviation Traders Carvairs to the fleet. These aircraft could transport five cars which were loaded into the fuselage through the nose of the aircraft. The Carvair proved to be uneconomical for the airline partly due to the rise of auto ferry services, and the aircraft were used for freight services until disposed of. The Boeing 720s proved to be a success for the airline on the transatlantic routes. To supplement these, Aer Lingus took delivery of its first larger Boeing 707 in 1964, and the type continued to serve the airline until 1986. A Boeing 720 in Aer Lingus-Irish International livery in 1965.

A Boeing 720 in Aer Lingus-Irish International livery in 1965.Jet aircraft

Conversion of the European fleet to jet equipment began in 1965 when the BAC One-Eleven started services on continental Europe.The airline adopted a new livery in the same year, with a large green shamrock on the fin. In 1966, the remainder of the company's shares held by Aer Rianta were transferred to the Minister for Finance. A Fokker F27 Friendship at Manchester Airport in 1965. The F27 was used on short-haul services between 1958 and 1966.In 1966, the company added routes to Montreal and Chicago. In 1968, flights from Belfast, in Northern Ireland, to New York City started, however, it was soon suspended due to the beginning of the Troubles.Aer Lingus introduced Boeing 737s to its fleet in 1969 to cope with the high demand for flights between Dublin and London. Later, Aer Lingus extended the 737 flights to all of its European networks. In 1967, after 30 years of service, General Manager Dr J.F. Dempsey signed the contract for the airline's first two Boeing 747 aircraft before he retired later that year.

A Fokker F27 Friendship at Manchester Airport in 1965. The F27 was used on short-haul services between 1958 and 1966.In 1966, the company added routes to Montreal and Chicago. In 1968, flights from Belfast, in Northern Ireland, to New York City started, however, it was soon suspended due to the beginning of the Troubles.Aer Lingus introduced Boeing 737s to its fleet in 1969 to cope with the high demand for flights between Dublin and London. Later, Aer Lingus extended the 737 flights to all of its European networks. In 1967, after 30 years of service, General Manager Dr J.F. Dempsey signed the contract for the airline's first two Boeing 747 aircraft before he retired later that year. An Aviation Traders Carvair that was used as a vehicle freighter is seen loading a car at Bristol Airport in 1964.

An Aviation Traders Carvair that was used as a vehicle freighter is seen loading a car at Bristol Airport in 1964. -

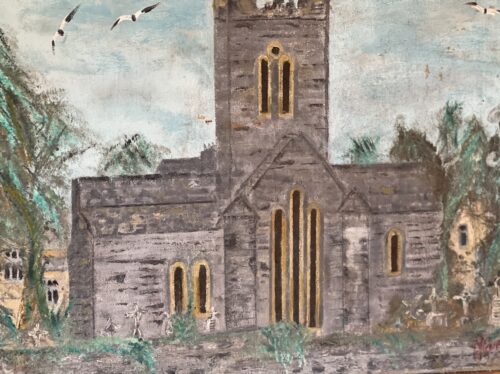

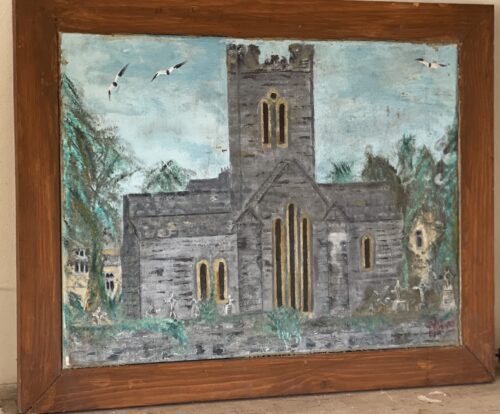

38cm x 48cm Killaloe Co Clare The Cathedral Church of St Flannan, Killaloe is a cathedral of the Church of Ireland in Killaloe, County Clare in Ireland. It is in the ecclesiastical province of Dublin. Previously the cathedral of the Diocese of Killaloe, it is now one of three cathedrals in the United Dioceses of Limerick and Killaloe. The Dean of the Cathedral is the Very Reverend Roderick Lindsay Smyth who is also Dean of Clonfert, Dean of Kilfenora and both Dean and Provost of Kilmacduagh.

38cm x 48cm Killaloe Co Clare The Cathedral Church of St Flannan, Killaloe is a cathedral of the Church of Ireland in Killaloe, County Clare in Ireland. It is in the ecclesiastical province of Dublin. Previously the cathedral of the Diocese of Killaloe, it is now one of three cathedrals in the United Dioceses of Limerick and Killaloe. The Dean of the Cathedral is the Very Reverend Roderick Lindsay Smyth who is also Dean of Clonfert, Dean of Kilfenora and both Dean and Provost of Kilmacduagh.Architecture

Killaloe Cathedral dates from the transition between the Romanesque and Gothic periods. The front is decorated with arabesque ornaments.On the north side of the cathedral is a small oratory or chapel of a date far prior to the cathedral; and probably the original sanctuary of the holy man who founded the abbey. Its roof is very deep, and made entirely of stone; it has a belfry, and two doorways to the east and west. In the bell tower is a chime of eight bells cast by Matthew O'Byrne of Dublin in 1896. The heaviest bell weighs just over 500 kilograms.Recent restoration

A £200,000 restoration project involving the repair of a Romanesque doorway and the reconstruction of a 12th-century high cross, was completed in 2001. The Kilfenora Cross, embedded in the walls of the Gothic cathedral in the 1930s, is once again free-standing. The imposing 12-ft monument is now in the nave of the building.Burials

Gallery

-

Killaloe Stone - front view with runic inscription

-

Killaloe Stone - side view with Ogham inscription

-

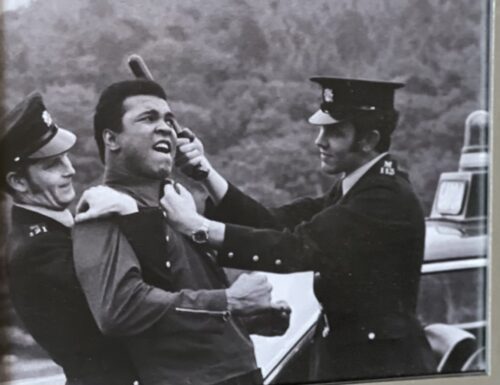

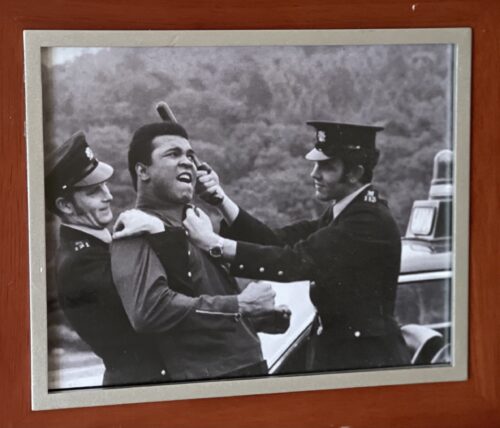

29cm x 36cm. Dublin Famous picture during The Greatest's visit to Ireland of Muhammad Ali play fighting with two members of An Garda Siochana.Some memory for those officers to tell their grandchildren about ! July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.

29cm x 36cm. Dublin Famous picture during The Greatest's visit to Ireland of Muhammad Ali play fighting with two members of An Garda Siochana.Some memory for those officers to tell their grandchildren about ! July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.Muhammad Ali's Irish roots explained

The astonishing fact that he had Irish roots, being descended from Abe Grady, an Irishman from Ennis, County Clare, only became known later in life. He returned to Ireland where he had fought and defeated Al “Blue” Lewis in Croke Park in 1972 almost seven years ago in 2009 to help raise money for his non–profit Muhammad Ali Center, a cultural and educational center in Louisville, Kentucky, and other hospices. He was also there to become the first Freeman of the town. The boxing great is no stranger to Irish shores and previously made a famous trip to Ireland in 1972 when he sat down with Cathal O’Shannon of RTE for a fascinating television interview. What’s more, genealogist Antoinette O'Brien discovered that one of Ali’s great-grandfathers emigrated to the United States from County Clare, meaning that the three-time heavyweight world champion joins the likes of President Obama and Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. as prominent African-Americans with Irish heritage. In the 1860s, Abe Grady left Ennis in County Clare to start a new life in America. He would make his home in Kentucky and marry a free African-American woman. The couple started a family, and one of their daughters was Odessa Lee Grady. Odessa met and married Cassius Clay, Sr. and on January 17, 1942, Cassius junior was born. Cassius Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali when he became a Muslim in 1964. Ali, an Olympic gold medalist at the 1960 games in Rome, has been suffering from Parkinson's for some years but was committed to raising funds for his center During his visit to Clare, he was mobbed by tens of thousands of locals who turned out to meet him and show him the area where his great-grandfather came from.Tracing Muhammad Ali's roots back to County Clare

Historian Dick Eastman had traced Ali’s roots back to Abe Grady the Clare emigrant to Kentucky and the freed slave he married. Eastman wrote: “An 1855 land survey of Ennis, a town in County Clare, Ireland, contains a reference to John Grady, who was renting a house in Turnpike Road in the center of the town. His rent payment was fifteen shillings a month. A few years later, his son Abe Grady immigrated to the United States. He settled in Kentucky." Also, around the year 1855, a man and a woman who were both freed slaves, originally from Liberia, purchased land in or around Duck Lick Creek, Logan, Kentucky. The two married, raised a family and farmed the land. These free blacks went by the name, Morehead, the name of white slave owners of the area. Odessa Grady Clay, Cassius Clay's mother, was the great-granddaughter of the freed slave Tom Morehead and of John Grady of Ennis, whose son Abe had emigrated from Ireland to the United States. She named her son Cassius in honor of a famous Kentucky abolitionist of that time. When he changed his name to Muhammad Ali in 1964, the famous boxer remarked, "Why should I keep my white slavemaster name visible and my black ancestors invisible, unknown, unhonored?" Ali was not only the greatest sporting figure, but he was also the best-known person in the world at his height, revered from Africa to Asia and all over the world. To the end, he was a battler, shown rare courage fighting Parkinson’s Disease, and surviving far longer than most sufferers from the disease. -

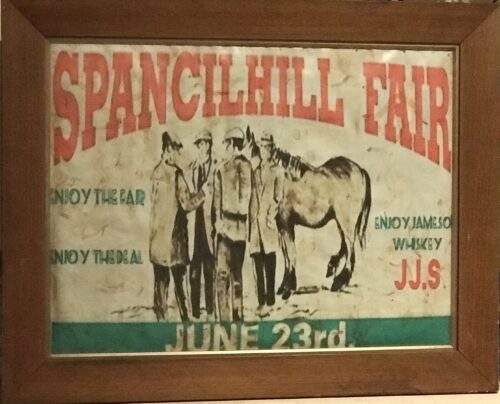

Very well reproduced and quaint advertisement for the legendary Fair of Spancil Hill,held every year on the 23rd of June -with Jameson Whiskey sponsoring the advert. Ennis Co Clare. 50 cm x 60cm Spancilhill is a small settlement in East County Clare that hosts an annual horse fair on the 23rd of June. The Spancilhill Horse Fair is Ireland’s oldest having been chartered in 1641 by Charles II. It derives its name from the Irish, Cnoc Fhuar Choille or Cold Wood Hill. The name was misinterpreted as Cnoc Urchaill or Spancel Hill. A spancel is a type hobble and its association with a horse fair perpetuated this misinterpretation. The 1913 fair saw four thousand horses for sale. The British, Belgian, and French armies sought cavalry mounts. The British army purchased 1,175 horses and lead them tied head to tail to Ennis for rail transport. Horse Fairs gained a reputation for wild behavior and animal cruelty. The Friends of the Spancilhill Horse Fair formed in the 1980s with the aim of restructuring the event as an agricultural show. Michael Considine, who emigrated from the area in 1870, composed the popular Irish folk ballad, Spancil Hill. Buyers across Europe attend with hopes to find international showjumping prospects. Photographers find the event irresistible and nearly outnumber the horses in recent times.The aforementioned song written about the fair has almost become more famous than the fair itself in modern times. Robbie McMahon was a songwriter and singer whose rendition of Spancil Hill is widely regarded as the definitive version. He reckoned he sang it more than 10,000 times since he learned it as a teenager.

Very well reproduced and quaint advertisement for the legendary Fair of Spancil Hill,held every year on the 23rd of June -with Jameson Whiskey sponsoring the advert. Ennis Co Clare. 50 cm x 60cm Spancilhill is a small settlement in East County Clare that hosts an annual horse fair on the 23rd of June. The Spancilhill Horse Fair is Ireland’s oldest having been chartered in 1641 by Charles II. It derives its name from the Irish, Cnoc Fhuar Choille or Cold Wood Hill. The name was misinterpreted as Cnoc Urchaill or Spancel Hill. A spancel is a type hobble and its association with a horse fair perpetuated this misinterpretation. The 1913 fair saw four thousand horses for sale. The British, Belgian, and French armies sought cavalry mounts. The British army purchased 1,175 horses and lead them tied head to tail to Ennis for rail transport. Horse Fairs gained a reputation for wild behavior and animal cruelty. The Friends of the Spancilhill Horse Fair formed in the 1980s with the aim of restructuring the event as an agricultural show. Michael Considine, who emigrated from the area in 1870, composed the popular Irish folk ballad, Spancil Hill. Buyers across Europe attend with hopes to find international showjumping prospects. Photographers find the event irresistible and nearly outnumber the horses in recent times.The aforementioned song written about the fair has almost become more famous than the fair itself in modern times. Robbie McMahon was a songwriter and singer whose rendition of Spancil Hill is widely regarded as the definitive version. He reckoned he sang it more than 10,000 times since he learned it as a teenager.The ballad is named after a crossroads between Ennis and Tulla in east Clare, the site of a centuries-old horse fair held every June. In 1870 a young man from the locality, Michael Considine, bade farewell to his sweetheart Mary McNamara and left for the US. He hoped to earn sufficient money to enable her to join him.

However, he died in California in 1873. Before his death he wrote a poem dedicated to Mary which he posted to his six-year-old nephew, John, back home.

Seventy years later McMahon was given the words at a house party. His singing of the ballad was warmly received by those in attendance, who included the author’s nephew, then an elderly man.

Many singers have recorded the ballad, but McMahon insisted his was the authentic version. He told The Irish Times in 2006: “Nowadays the song is not sung correctly. Many singers put words that are not in it [at] all, singing stuff like ‘Johnny, I love you still’. There’s no ‘Johnny’ in that song.” The late writer Bryan MacMahon was an early admirer of his namesake’s talent and had high praise for his ability as a performer and entertainer.

Singer Maura O’Connell warmed to Robbie McMahon’s “great big personality”, and said that he made Spancil Hill his own.

Born in 1926, he was the third youngest of 11 children, one of whom died in childhood, and grew up on his father’s farm in Clooney, near Ennis. There was music in the family, and all the children sang. Young Robbie was something of a mischief-maker, hence the title of an album he recorded later in life – The Black Sheep.

He began singing in public at the age of 18, and went on to win 16 all-Ireland titles at fleadhanna around the country. In the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s he toured Britain and the US with a troupe of traditional musicians under the auspices of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann.

As a songwriter, he is best known for the Fleadh Down in Ennis, which celebrates the 1956 all-Ireland fleadh cheoil. Other compositions include Come on the Banner, the Red Cross Social and the Feakle Hurlers, in honour of the 1988 Clare county champions.

A lilter, he was renowned for his performance of the Mason’s Apron, in which he simulated the sound of both the fiddle and accompanying banjo.

Possessed of a store of jokes, ranging from the hilarious to the unprintable, he was as much a character as a singer and was more comfortable with the craic and banter of casual sessions than with formal concerts.

He was the subject of a film documentary Last Night As I Lay Dreaming. Clare County Council hosted a civic reception in his honour in 2010, and he was the recipient of the Fleadh Nua Gradam Ceoil in 2011.

He is survived by his wife Maura, daughters Fiona, Noleen and Dympna and son Donal.

-

35cm x 45cm. Dublin Extraordinary moment captured in time as a seemingly cordial Eamon De Valera & Michael Collins plus Arthur Griffith and Lord Mayor of Dublin Laurence O'Neill enjoying each others company at Croke Park for the April 6, 1919 Irish Republican Prisoners' Dependents Fund match between Wexford and Tipperary. Staging Gaelic matches for the benefit of the republican prisoners was one of the ways in which the GAA supported the nationalist struggle. How so much would change between those two behemoths of Irish History-Collins and De Valera over the next number of years.

35cm x 45cm. Dublin Extraordinary moment captured in time as a seemingly cordial Eamon De Valera & Michael Collins plus Arthur Griffith and Lord Mayor of Dublin Laurence O'Neill enjoying each others company at Croke Park for the April 6, 1919 Irish Republican Prisoners' Dependents Fund match between Wexford and Tipperary. Staging Gaelic matches for the benefit of the republican prisoners was one of the ways in which the GAA supported the nationalist struggle. How so much would change between those two behemoths of Irish History-Collins and De Valera over the next number of years. -

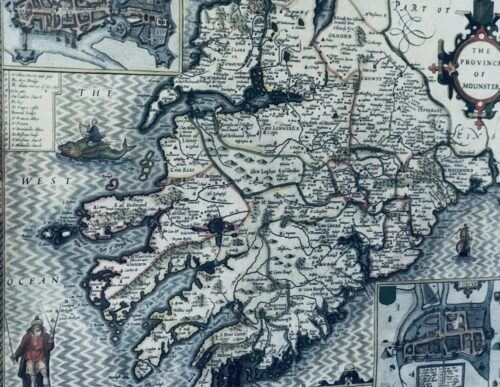

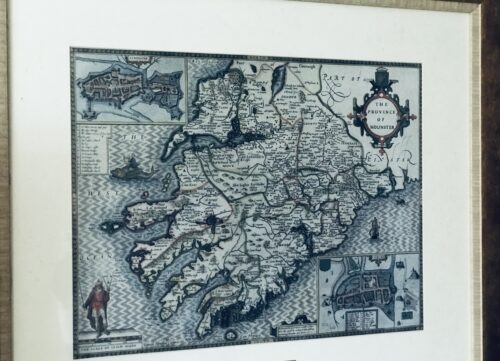

Fascinating map from 1610 as by the renowned cartographer John speed of the Province of Mounster(Munster!)-comprising the counties of Tipperary,Clare,Limerick,Cork,Kerry & Waterford.Includes miniature city layouts of both Limerick & Cork. 52cm x 65cm Beaufort Co Kerry John Speed (1551 or 1552 – 28 July 1629) was an English cartographer and historian. He is, alongside Christopher Saxton, one of the best known English mapmakers of the early modern period.

Fascinating map from 1610 as by the renowned cartographer John speed of the Province of Mounster(Munster!)-comprising the counties of Tipperary,Clare,Limerick,Cork,Kerry & Waterford.Includes miniature city layouts of both Limerick & Cork. 52cm x 65cm Beaufort Co Kerry John Speed (1551 or 1552 – 28 July 1629) was an English cartographer and historian. He is, alongside Christopher Saxton, one of the best known English mapmakers of the early modern period.Life

Speed was born in the Cheshire village of Farndon and went into his father Samuel Speed's tailoring later in life. While working in London, Speed was a tailor and member of a corresponding guild, and came to the attention of "learned" individuals. These individuals included Sir Fulke Greville, who subsequently made him an allowance to enable him to devote his whole attention to research. By 1598 he had enough patronage to leave his manual labour job and "engage in full-time scholarship". As a reward for his earlier efforts, Queen Elizabethgranted Speed the use of a room in the Custom House. Speed, was, by this point, as "tailor turned scholar" who had a highly developed "pictorial sense". In 1575, Speed married a woman named Susanna Draper in London, later having children with her. These children definitely included a son named John Speed, later a "learned" man with a doctorate, and an unknown number of others, since chroniclers and historians cannot agree on how many children they raised. Regardless, there is no doubt that the Speed family was relatively well-off. By 1595, Speed published a map of biblical Canaan, in 1598 he presented his maps to Queen Elizabeth, and in 1611–1612 he published maps of Great Britain, with his son perhaps assisting Speed in surveys of English towns. At age 77 or 78, in August 1629, Speed died. He was buried alongside his wife in London's St Giles-without-Cripplegate church on Fore Street. Later on, a memorial to John Speed was also erected behind the altar of the church.According to the church's website, "[His was] one of the few memorials [in the church] that survived the bombing" of London during The Blitz of 1940–1941 ... The website also notes that "[t]he cast for the niche in which the bust is placed was provided by the Merchant Taylors' Company, of which John Speed was a member". His memorial brass has ended up on display in the Burrell Collection near Glasgow.Works

Speed drew historical maps in 1601 and 1627 depicting the invasion of England and Ireland, depictions of the English Middle Ages, along with those depicting the current time, with rough originals but appealing, colourful final versions of his maps. It was with the encouragement of William Camden that Speed began his Historie of Great Britaine, which was published in 1611. Although he probably had access to historical sources that are now lost to us (he certainly used the work of Saxton and Norden), his work as a historian is now considered secondary in importance to his map-making, of which his most important contribution is probably his town plans, many of which provide the first visual record of the British towns they depict.In the years leading up to this point, while his atlas was being compiled, he sent letters to Robert Cotton, part of the British government to ask for assistance in gathering necessary materials.His atlas The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine was published in 1611 and 1612, and contained the first set of individual county maps of England and Wales besides maps of Ireland and a general map of Scotland. Tacked onto these maps was an introduction at the beginning when he addressed his "well affected and favourable reader", which had numerous Christian and religious undertones, admitting that there may be errors, but he made it the best he could, and stated his purpose for the atlas:my purpose...is to shew the situation of every Citie and Shire-town only [within Great Britain]...I have separated...[with] help of the tables...any Citie, Towne, Borough, Hamlet, or Place of Note...[it] may be affirmed, that there is not any one Kingdome in the world so exactly described...as is...Great Britaine...In shewing these things, I have chiefly sought to give satisfaction to all.

With maps as "proof impressions" and printed from copper plates, detail was engraved in reverse with writing having to be put on the map the correct way, while speed "copied, adapted and compiled the work of others", not doing much of the survey work on his own, which he acknowledged.The atlas was not above projections of his political opinions" Speed represented King James I as one who unified the "Kingdoms of the British isles". In 2016, the British Library published a book, introduced by former MP Nigel Nicolson and accompanied by commentaries by late medieval and early modern historian Alasdair Hawkyard, which reprinted this collection of maps on the British Isles, showing that Speed had drawn maps of areas ranging from Bedfordshire to Norfolk and Wales. Most, but not all, of the county maps have town plans on them; those showing a Scale of Passes being the places he had mapped himself. In 1627, two years before his death, Speed published Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World which was the first world atlas produced by an Englishman, costing 40 shillings, meaning that its circulation was limited to "richer customers and libraries", where many survive to this day. There is a fascinating text describing the areas shown on the back of the maps in English, although a rare edition of 1616 of the British maps has a Latin text – this is believed to have been produced for the Continental market. Much of the engraving was done in Amsterdam at the workshop of a Flemish man named Jodocus Hondius, with whom he collaborated with from 1598 until 1612, with Hondius's sudden death, a time period of 14 years.His maps of English and Welsh counties, often bordered with costumed figures ranging from nobility to country folk, are often found framed in homes throughout the United Kingdom. In 1611, he also published The genealogies recorded in the Sacred Scriptures according to euery family and tribe with the line of Our Sauior Jesus Christ obserued from Adam to the Blessed Virgin Mary, a biblical genealogy, reprinted several times during the 17th century. He also drew maps of the Channel Islands, Poland, and the Americas, the latter published only a few years before his death. On the year of his death, yet another collection of maps of Great Britain he had drawn the year before were published. Described as a "Protestant historian", "Puritan historian" or "Protestant propagandist" by some, Speed wrote about William Shakespeare, whom he called a "Superlative Monster" because of certain plays, Roman conquest, history of Chester, and explored "early modern concepts of national identity". As these writings indicate, he possibly saw Wales as English and not an independent entity. More concretely, there is evidence that Speed, in his chronicling of history, uses "theatrical metaphors" and his developed "historiographic skill" to work while he repeats myths from medieval times as part of his story.Legacy

Since his maps were used in many high circles, Speed's legacy has been long-reaching. After his death, in 1673 and 1676, some of his other maps on the British isles, the Chesapeake Bay region, specifically of Virginia and Maryland, the East Indies, the Russian Empire then ruled by Peter the Great, Jamaica, and Barbados, among other locations.With these printings and others, Speed's maps became the basis for world maps until at least the mid-eighteenth century, with his maps reprinted many times, and served as a major contribution to British topography for years to come. In later years, Speed would be called "our English Mercator", a person of "extraordinary industry and attainments in the study of antiques", an "honest and impartial historian", a "faithful Chronologer", and "our Cheshire historian...a scholar...a distinguished writer on history".He was also called a "celebrated chronologer and histographer", "cartographer", and much more. Even today, prints of his "beautiful maps" can be found in living rooms across the world, and sell for hundreds of thousands of pounds in rare art and map auctions, drawing in map collectors across the globe.Additionally, some use John Speed's maps, and connected commentary, to interpret William Shakespeare's plays; however, Speed did not like Shakespeare in the slightest, and called him a "papist". -

cm x cm Askeaton Co Limerick

‘Our seducers were our accusers’: the lurid tales of members of Askeaton Hellfire Club

The ruins of Askeaton Hellfire Club on an island in the River Deel, with the ruins of the Desmond Castle in the background (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2017) Patrick Comerford The ruins of Limerick Hellfire Club stand beside the ruins of the Desmond Castle on the island in the middle of the River Deel. As the fast-flowing waters of the river thunder past, making their way under the old narrow bridge, these ruins appear like a benign presence in the heart of the town, especially in the early evening as the sun sets behind them and the rooks and herons hover above the remains of this centuries-old crumbling structures. The ruins of the Hellfire Club stand within the bailey of Askeaton Castle. They date from 1636-1637, when this building was first erected as a detached barracks or tower. The barracks or tower was built by the builder and designer, Andrew Tucker, for Richard Boyle (1566-1643), the 1st Earl of Cork, who had recently acquired Askeaton Castle. The tower was built with battered walls with cut stone quoins, and the remains of a three-bay was built on top of the battered base later, some time in the mid-18th century. There is a bow to the south elevation of the house and a shallow projecting end-bay to the north elevation. The house is roofless, with a limestone eaves course. The course rubble limestone walls have tolled quoins, a brick stringcourse and brick quoins to the upper floors. There are square-headed door openings to the north elevation, a square-headed window opening to the bow with a brick architrave, and camber-headed window openings to the west, with brick voussoirs. The round-headed window opening to the east elevation has a brick surround, flanked by round-headed niches with brick surrounds and a continuous brick sill course. By 1740, the building belonged to the St Leger family, who may have engaged John Aheron to design the bow-sided house which was built on top of the base of the barracks. By then, this was the meeting place of the Askeaton Hell Fire Club, and the building was probably used by the club until the end of the 18th century. The club in Askeaton traced its origins to the first Hellfire Club, formed in 1719 by Philip Wharton (1698-1731), 1st Duke of Wharton. Wharton was a rake who gamble away Rathfarnham Castle in Dublin and most of his inheritance. In 1726, he married Maria Theresa O’Beirne (sometimes known as Maria Theresa Comerford). When he was in the advanced stages of alcoholism, the couple moved to a Cistercian abbey in Catalonia, where he died in 1731. His widow returned to London, and after his will was proved in court she lived comfortably in London society. The club continued long after Wharton’s death, and the club in Askeaton was founded around 1736-1740. Known as a satirical gentlemen’s club, the revelries of its members shocked their neighbours and the outside world. The two other clubs in Ireland were based on Montpelier Hill, south of Tallaght, and near Clonlara, Co Clare. In his recent book Blasphemers & Blackguards, The Irish Hellfire Clubs (2012), David Ryan examines the stories of these clubs. But, while local folklore recalls lurid tales of outrageous rituals, there is little actual information or evidence of the activities of the Askeaton Hellfire Club, and the name and supposedly lurid activities may have been opportunities to slight the church and to snub clerical authority, or mere excuses to hide their debauchery during evenings of wine, women and song. James Worsdale’s painting of the members of the Askeaton Hellfire Club One tradition recalls how a member of the club was thrown from one of the windows into the River Deel below during the course of a ‘drunken frolic.’ Evidence of the club and its members survives in a painting by James Worsdale (1692-1767) from sometime between 1736 and 1740. This painting shows a group of club members in Askeaton drinking, smoking and in conversation. Bottles of wine sit on a rack in the foreground, and there is a large bowl of punch on the table. Eleven men and one woman, as well as a boy, fill the painting. Some of the figures that have been identified include: Edward Croker of Ballingarde, his son John (died 1804); Wyndham Quin of Adare, father of the 1st Earl of Dunraven; Thomas Royce of Nantenan, near Askeaton; John Bayley of Debsborough, Nenagh, Co Tipperary; and Henry Prittie, father of Henry Prittie (1743-1801), father of Lord Dunalley. Worsdale, who was a founding member of the Dublin Hellfire Club, is on the far left of the painting, trying to attract the attention of the only woman in the painting. Most critics identify this woman as Margaret Blennerhassett, who was known as Celinda and who was the wife of Arthur Blennerhassett, a magistrate, of Riddlestown Park, Rathkeale. She was born Margaret Hayes, the eldest daughter of Jeremiah Hayes of Cahir Guillamore, Bruff. Celinda is said to have been the only woman who ever became a member of the Askeaton Hellfire Club. The story is told that in her curiosity she tried to find what the men did during their meetings at the club. She hid herself in the meeting room before the members arrived, and when they discovered her she was formally inducted as a member to ensure her silence. Later, her husband drowned in a boating tragedy in the Lakes of Killarney in 1775. Some critics, however, have identified the woman in this painting as Laetitia Pilkington, alongside her husband, the Revd Matthew Pilkington (1701-1774), one-time friends of Jonathan Swift, Dean of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin. This would date the painting from some time before 1738. Matthew Pilkington moved to London, where he became friends with the painter James Worsley, led a dissolute life, divorced Laetitia, and was jailed in 1734. When he returned to Ireland, he enjoyed the patronage of Archbishop Michael Cobbe of Dublin and the Cobbe family of Newbridge House, Donabate. Laetitia Pilkington (1709-1750), was the daughter of a Dublin obstetrician, Dr John van Lewen. After Matthew fabricated the circumstances that led to their divorce, she was arrested for a debt of £2 and ended up in a debtors’ prison in London. If she was forced into discreet prostitute to earn a living later in life, she was also scathingly critical of the clergy of day. Speaking probably from the experience of her husband’s own lifestyle, she said ‘the holiness of their office gives them free admittance into every family’ and they abuse this so that ‘they are generally the first seducers of innocence.’ ‘Our seducers were our accusers,’ she wrote. The monument in Saint Ann’s Church, Dawson Street, Dublin, commemorating Laetitia Pilkington (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2017) When Laetitia Pilkington died in 1750, a monument was erected in Saint Ann’s Church, Dawson Street, Dublin, with clear references to the sufferings she had endured at the hands of her merciless husband. Less than a month after her death, Matthew Pilkington married his mistress Nancy Sandes. In 1811, an evangelical magazine published an obituary of Captain Perry, a carousing individual and likely member of a Hellfire Club. After a short lifetime of excessive living and radical thinking, he died an early death as he struggled to repent. It was a warning to readers of the dangers of being involved in such circles. The building was abandoned by the club sometime around 1840, and the club is inaccessible to the public, as the Office of Public Works continues work at stabilising the building. The Limerick Leader in May 1958 that James Worsdale’s painting of the members of the Askeaton Hellfire Club was being offered for sale to Limerick City Council for £350. It is now in the National Gallery of Ireland. Although the ruins of the Askeaton Hellfire Club have fallen into disrepair, the overall original form of this building is easily discerned, as are features such as the door and window openings. It retains many well-crafted features such as the brick window surrounds and limestone battered walls, and the high roof and the tall chimneys are of interest. The building has a curved bow at one side of each of the building’s two principal fronts, and one of them has a Venetian window. If, as is possible, the house dates from the 17th century, then this could be one of the earliest known examples of a Venetian window on a curve, not just in Ireland but anywhere else in Europe – which could just make it a far more interesting building than the myths and legends surrounding its rakish revellers. Sunset at Askeaton Castle and Hellfire Club, seen from Saint Mary’s Church (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2017)