-

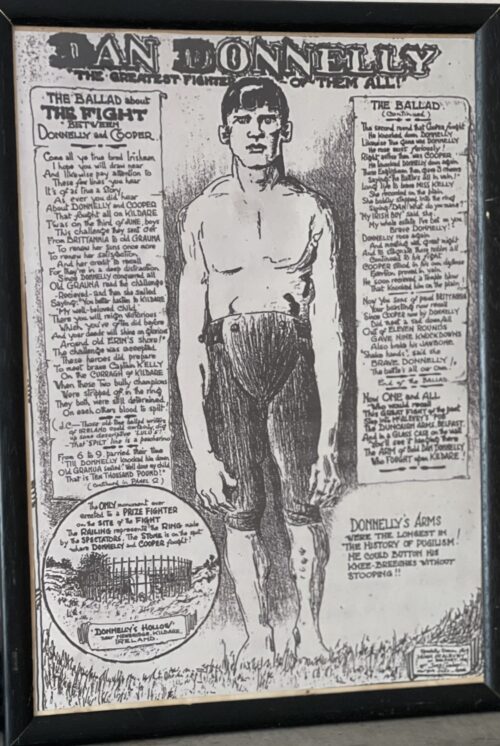

46cm x 32cm Dublin Daniel Donnelly (March 1788 – 18 February 1820) was a professional boxing pioneer and the first Irish-born heavyweight champion. He was posthumously inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, Pioneers Category in 2008. Donnelly was born in the docks of Dublin, Ireland in March 1788. He came from a family of seventeen children.Donnelly grew up in poverty; his father was a carpenter, but suffered from chest complaints and was frequently out of work. As soon as he was able, Donnelly also went to work as a carpenter. On the streets of Dublin, Donnelly had a reputation of being a hard man to provoke, but was known to be "handy with his fists", and he became the district's new fighting hero.There are a number of anecdotes about Donnelly's life in this period, including his rescue of a young woman being attacked by two sailors at the dockside, leading to his arm being badly mangled. He was taken to the premises of the prominent surgeon Dr. Abraham Colles who saved Donnelly's arm from amputation, describing him as a "pocket Hercules". Another tale concerns Donnelly's insistence of carrying the body of an old lady who had died of a highly contagious fever to a local graveyard, where he buried the body himself in a grave that had been "reserved for a person of distinction".Boxing at that time was very different from the boxing of today. There were few rules. There was no boxing organization to oversee the sport or lay down regulations or procedures. There was no formal end to the fights: they would go on until one fighter was unable to continue or would give up. A now obsolete practice was that of the seconds. The seconds would wait in the ring during the fight, and assist the boxer between rounds. There were no restrictions regarding fight tactics. For example, a fighter could hit his opponent's head off a corner post, or wrestle his opponent to the ground, or pull his hair, or wrap his arm around his neck in a choking motion and then hit him in the face with the other hand. The fights were very severe and often brutal, and they would continue until the end. A round could last as long as six or seven minutes, or a little as 30 seconds. The round would end when one person was on the ground. He would then have 30 seconds to get up and continue the fight. For a few rounds, Hall was showing his skill was paramount. He scored first blood, which was an important occasion in bare-fist boxing; there were bets made on who would draw first blood. But as the rounds went on, Donnelly's strength began to tell. Hall would slip down onto his knee, without being in any danger. This was a tactic, because once he went down the round was over, he got a 30-second rest, and came back refreshed. He was doing this just a bit too often for Donnelly's liking, and at one stage, Donnelly was just about to lash out when he was down, and his second shouted out an admonishment that Dan would lose the fight if he did so. Eventually he did lose his temper, and as Hall slipped down yet again, Donnelly lashed out and hit him on the ear; the blood flowed. That was the end of the round. Hall refused to continue, saying he had been fouled, that Donnelly should be disqualified. Donnelly fans voiced that no, Dan had definitely won, Hall didn't want to fight on, Donnelly was the champion. The fight ended in some controversy, but to the Irish, he was the conquering hero. Belcher's Hollow was rechristened Donnelly's Hollow and Dan Donnelly was now acclaimed as Ireland's Champion.For a short while, at least, the country celebrated its new hero. The Irish saw sporting heroes like Dan Donnelly as the symbolic winner of the bigger fight. While Ireland was left without its own government, England was becoming increasingly more powerful. Whenever Dan's right hand bloodied an English nose, it was hailed as a strike, however small, against the oppressors.

46cm x 32cm Dublin Daniel Donnelly (March 1788 – 18 February 1820) was a professional boxing pioneer and the first Irish-born heavyweight champion. He was posthumously inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, Pioneers Category in 2008. Donnelly was born in the docks of Dublin, Ireland in March 1788. He came from a family of seventeen children.Donnelly grew up in poverty; his father was a carpenter, but suffered from chest complaints and was frequently out of work. As soon as he was able, Donnelly also went to work as a carpenter. On the streets of Dublin, Donnelly had a reputation of being a hard man to provoke, but was known to be "handy with his fists", and he became the district's new fighting hero.There are a number of anecdotes about Donnelly's life in this period, including his rescue of a young woman being attacked by two sailors at the dockside, leading to his arm being badly mangled. He was taken to the premises of the prominent surgeon Dr. Abraham Colles who saved Donnelly's arm from amputation, describing him as a "pocket Hercules". Another tale concerns Donnelly's insistence of carrying the body of an old lady who had died of a highly contagious fever to a local graveyard, where he buried the body himself in a grave that had been "reserved for a person of distinction".Boxing at that time was very different from the boxing of today. There were few rules. There was no boxing organization to oversee the sport or lay down regulations or procedures. There was no formal end to the fights: they would go on until one fighter was unable to continue or would give up. A now obsolete practice was that of the seconds. The seconds would wait in the ring during the fight, and assist the boxer between rounds. There were no restrictions regarding fight tactics. For example, a fighter could hit his opponent's head off a corner post, or wrestle his opponent to the ground, or pull his hair, or wrap his arm around his neck in a choking motion and then hit him in the face with the other hand. The fights were very severe and often brutal, and they would continue until the end. A round could last as long as six or seven minutes, or a little as 30 seconds. The round would end when one person was on the ground. He would then have 30 seconds to get up and continue the fight. For a few rounds, Hall was showing his skill was paramount. He scored first blood, which was an important occasion in bare-fist boxing; there were bets made on who would draw first blood. But as the rounds went on, Donnelly's strength began to tell. Hall would slip down onto his knee, without being in any danger. This was a tactic, because once he went down the round was over, he got a 30-second rest, and came back refreshed. He was doing this just a bit too often for Donnelly's liking, and at one stage, Donnelly was just about to lash out when he was down, and his second shouted out an admonishment that Dan would lose the fight if he did so. Eventually he did lose his temper, and as Hall slipped down yet again, Donnelly lashed out and hit him on the ear; the blood flowed. That was the end of the round. Hall refused to continue, saying he had been fouled, that Donnelly should be disqualified. Donnelly fans voiced that no, Dan had definitely won, Hall didn't want to fight on, Donnelly was the champion. The fight ended in some controversy, but to the Irish, he was the conquering hero. Belcher's Hollow was rechristened Donnelly's Hollow and Dan Donnelly was now acclaimed as Ireland's Champion.For a short while, at least, the country celebrated its new hero. The Irish saw sporting heroes like Dan Donnelly as the symbolic winner of the bigger fight. While Ireland was left without its own government, England was becoming increasingly more powerful. Whenever Dan's right hand bloodied an English nose, it was hailed as a strike, however small, against the oppressors. -

35cm x 45cm Caherciveen Co Kerry Framed print of one of there greatest Gaelic Footballers of all time - the legendary Mick O'Connell. Michael "Mick" O'Connell (born 4 January 1937) is an Irish retired Gaelic footballer. His league and championship career with the Kerry senior team spanned nineteen seasons from 1956 to 1974. O'Connell is widely regarded as one of the greatest players in the history of the game. Born on Valentia Island, County Kerry, O'Connell was raised in a family that had no real link to Gaelic football. In spite of this he excelled at the game in his youth and also at Cahersiveen CBS. By his late teens O'Connell had joined the Young Islanders, and won seven South Kerry divisional championship medals in a club career that spanned four decades. He also lined out with South Kerry, winning three county senior championshipmedals between 1955 and 1958. O'Connell made his debut on the inter-county scene at the age of eighteen when he was selected for the Kerry minor team. He enjoyed one championship season with the minors, however, he was a Munster runner-up on that occasion. O'Connell subsequently joined the Kerry senior team, making his debut during the 1956 championship. Over the course of the next nineteen seasons, he won eight All-Ireland medals, beginning with lone triumphs in 1959 and 1962, and culminating in back-to-back championships in 1969 and 1970. O'Connell also won twelve Munster medals, six National Football League medals and was named Footballer of the Year in 1962. He played his last game for Kerry in July 1974. Recollecting his early years on RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta and Radio Kerry, O’Connell spoke of how he was introduced to Gaelic football.He also revealed he had regularly played soccer with Spanish fishermen on his native Valentia Island. “Well, I remember I was 11 or 12, my father bought them (boots) in the shop in Cahirsiveen. I remember playing beside the house at home and I remember the first day I got those from the shop I was delighted. But after that there wasn’t a lot of people with football boots. “We would play barefoot often during the summer — and we were happy to play barefoot — that’s the way it was back then. “My father bought us a ball, a size 4. It wasn’t too big but it was fine. We would play at home and coming home from school a lot of people would come in playing with us, schoolboys, and often, very often, the Spanish would come in taking shelter from the weather, they would come in and play soccer with us. “If there was bad weather, they’d take shelter here in the harbour. They wouldn’t have a penny but a drop of wine in bags but they had no money and they’d come in and play. It was nice to watch them. I was practicing left and right but we had no trainers or coaches at the time. It was just a case of practicing between ourselves, nice and gently. There were no matches but games between ourselves and that’s all we had at the time.” It was O’Connell’s father Jeremiah who helped begin his son’s love of Gaelic football although he himself had no background in the game. “My own mother (Mary), she was never at a match and my uncle who was born in 1880 or that, he was living with us on Valentia Island, he was never at a match.“My father had an interest every now and again going to the matches. I remember them coming from Portmagee, Derrynane and Cahirciveen to play. That’s when I remember feeling that was something special about playing sport. “I remember going to a game on a boat with my father. The Islanders were playing, that was in 1945, and those memories from long ago come back to me every so often. And a lot of those players and a lot of the inter-county players are dead now. But I remember the first time I played in a Munster final in Killarney, in 1956, and only two of those players are still alive (Tom Long and Seán Ó Murchú).” But for a job in which he worked at for most of his Kerry playing days, O’Connell said he would never have worn the green and gold. “Between 1956 and ‘66, I worked for the Western Union company on Valentia Island, five full days and a half day on Saturday. It was a very useful job; it facilitated me in a great way. Otherwise, it was a job that would be too demanding and it also meant I was free at the weekends. “Any person playing amateur sport without an appropriate job would find it very hard to find perfection in it. Otherwise, I would never have played for Kerry.” O’Connell has questioned the Government’s grants scheme for inter-county Gaelic players. The Valentia Island man believes the funding mechanism, which will rise to €3 million per annum by 2018, has been signed off without the authority of the Irish tax-payers.Interviewed by Raidió na Gaeltachta on his 80th birthday yesterday, O’Connell criticised the Government for what he determines as directing remuneration towards county footballers and hurlers. “I have no involvement in the games today, except for watching it, but something I don’t agree with... it’s okay for the GAA to generate money in Croke Park and to spend it on the players if they want to, but I don’t agree at all that Government money, money of the Government of Ireland collected through taxes from the ordinary person, is being paid to the players. “I don’t think they have any permission to do that. That money should be spent on health and education rather than what’s being done now that I read in the paper, which is the way it is now.” In a wide-ranging interview with Helen Ní Shé on the An Saol ó Dheas programme, O’Connell also took a dim view of outgoing Kerry minor footballer Mark O’Connor’s switch to AFL club Geelong on a two-year rookie contract. “I’m not too impressed with that game in Australia at all. If Gaelic football was played properly, without pulling and dragging out of each other, and things like that, it would be a much better game than the game in Australia. “But again, in this country, the money isn’t in this country to give money to the players professionally at all and people have jobs now. If they had a good job and time to train, it’s a pastime. It’s a pastime. “Sport is a pastime. And people are saying there is pressure on them because they have to train... it’s a pastime for the trainer too, meeting and in contact with people the same age as them and things like that. That’s a great thing.” O’Connell doesn’t buy the idea more Gaelic players want to be involved in a full-time sport“Ah, that’s the kind of talk the media presents before them, that there is pressure on them. Give it up if you’re not happy, that’s the way it should be. To be good at anything, you enjoy anything that you’re good at, and practice that, you understand.” He marvels at what modern day players are provided with. “They have the facilities now. The facilities weren’t there long ago. But they have a lot of facilities now. Look at Fitzgerald Stadium in Killarney, there wasn’t a stand, there wasn’t a dressing room or anything when I started playing. As far as I remember, I don’t know what you called it, the mental hospital, we had a room in that place where we togged out. Every place throughout Kerry and throughout Ireland, the facilities are at a very high standard now in comparison to years ago.” Speaking to Jerry O’Sullivan on Radio Kerry’s Kerry Today programme, O’Connell bemoaned where Gaelic football was going and the negativity attached to it.“The (current) game doesn’t appeal to me. For me anyway it was always ball first, man second. To try and negate the other player it wasn’t my style.” O’Connell insisted he wasn’t criticising current players but the game itself and how it was taken too much from other codes. Although the mark has been championed as a means of safeguarding the high-fielding O’Connell was renowned for, he sees it as another example of a foreign rule. Even in my own time, there was no clear-cut set of rules stated in print for a referee. “I always thought as a player that a referee’s job should be almost to mark the scores and players playing the game should know what the game was and play accordingly.O’Connell continued: “Gaelic football has been played for about 120 years or whatever so and there is no bit of original wisdom within it to have your own game and to be powerful of your own game and not to be borrowing from other (sports), mark or no mark, red card, yellow card. It’s borrowing from other codes and that’s the negativity. It’s been always there, especially so now.” In an at times awkward conversation on Newstalk’s Off The Ball last night, O’Connell played down the significance of his sporting accomplishments. “Winning the game was not triumph and losing the game was not disaster. It was winning and losing games and that was all part of sport.” He remarked he had no passion in life. “Passion in life? None. None whatsoever. Playing football afforded me the chance to do exercise and play games locally and sometimes in Dublin. It was a nice way of associating with other people and so on. “It wasn’t a passion as such. Some people might think because living on an island (that it was) but it just happened that I occurred to be very good at it and got my place on the county team and got some games in Dublin.” He admitted his reluctance with the adulation he has received over the years. “That’s only comment. There’s no such thing as one player being better than the next because football is about a style of play. Some people have different styles and if one style satisfies some people other people might like the do-or-die effort. “Beloved? I don’t know what that means. If your style of play satisfies, all well and good but maybe I wasn’t ruthless enough. I wouldn’t do anything to win. The end to me wasn’t as important as the means. The means in which I played was a justification and if it won all well and good. “When I see people talking about Kerry beaten and a disastrous result, there is no such thing in the game of sport. Win or lose, you take your win or your beating in your stride, that’s it. “Another thing, coming from Valentia Island, I was kind of unique. Being an islander, it was unusual and that was why a lot of attention was put on me. It was difficult because you had difficult, bad weather sometimes here and you could never really practice to your extent. “That was often attributed to me, being in a kind of an unique and odd situation, that there must be something strange about a person to play from an island. It wasn’t. It was the game, the code of the area, and I played from an early age. “It wasn’t the be-all and end-all because in my household there was no discussion on football.” ‘Any day if I caught a few good balls and kicked a few good balls, that was success’ Mick O’Connell says the simple satisfaction of having “caught a few good balls and kicked a few good balls” is what remains with him most from his playing time with Kerry. Looking back, he doesn’t like to use the word “career” and when asked if the battles with the famed Galway of the 1960s were what come back to him most he replied: “I enjoyed all games whether it was here in Cahirsiveen, Tralee, Fitzgerald Stadium or New Ross, Tuam or any other place I was. “Any day if I caught a few good balls and kicked a few good balls that was success. “I played in 10 All-Irelands and lost a bigger percentage than I won (four victories). So be it, I had involvement. Success is a bit sweeter when you taste a bit of defeat as well. “That was my view. Looking back on it, it gave me a great association with people from different parts of Kerry and different parts of Ireland and abroad as well. Sport was a great dimension to my life but not everything.” O’Connell also returned to 1959 when he captained Kerry to an All-Ireland crown and left the Sam Maguire Cup in the dressing room. “I got the cup from Dr (Joseph) Stuart who was the president of the GAA at the time and my knee was injured the same day. I left the cup in the dressing room and I came home on the train and people asked me the reason I didn’t take the Sam Maguire with me. It was the team’s cup, I was no bigger than any other member of the team. The people who were in charge should have taken it home. It came home to the island a few weeks or so afterwards.”He doesn’t know the location of his four Celtic Crosses. “It doesn’t matter. I don’t know. I gave one of them to somebody. There was a raffle or something on years ago.”“The purpose of the game was to deliver it (the ball) as distinct from now when carrying the ball, running with it and passing with it. That’s the big change. I don’t blame the players at present. It’s very confusing. Even in my time, the elders never clearly stated a rule about obstruction or anything like that. It’s very hard in Ireland to get a discussion on the game.”

35cm x 45cm Caherciveen Co Kerry Framed print of one of there greatest Gaelic Footballers of all time - the legendary Mick O'Connell. Michael "Mick" O'Connell (born 4 January 1937) is an Irish retired Gaelic footballer. His league and championship career with the Kerry senior team spanned nineteen seasons from 1956 to 1974. O'Connell is widely regarded as one of the greatest players in the history of the game. Born on Valentia Island, County Kerry, O'Connell was raised in a family that had no real link to Gaelic football. In spite of this he excelled at the game in his youth and also at Cahersiveen CBS. By his late teens O'Connell had joined the Young Islanders, and won seven South Kerry divisional championship medals in a club career that spanned four decades. He also lined out with South Kerry, winning three county senior championshipmedals between 1955 and 1958. O'Connell made his debut on the inter-county scene at the age of eighteen when he was selected for the Kerry minor team. He enjoyed one championship season with the minors, however, he was a Munster runner-up on that occasion. O'Connell subsequently joined the Kerry senior team, making his debut during the 1956 championship. Over the course of the next nineteen seasons, he won eight All-Ireland medals, beginning with lone triumphs in 1959 and 1962, and culminating in back-to-back championships in 1969 and 1970. O'Connell also won twelve Munster medals, six National Football League medals and was named Footballer of the Year in 1962. He played his last game for Kerry in July 1974. Recollecting his early years on RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta and Radio Kerry, O’Connell spoke of how he was introduced to Gaelic football.He also revealed he had regularly played soccer with Spanish fishermen on his native Valentia Island. “Well, I remember I was 11 or 12, my father bought them (boots) in the shop in Cahirsiveen. I remember playing beside the house at home and I remember the first day I got those from the shop I was delighted. But after that there wasn’t a lot of people with football boots. “We would play barefoot often during the summer — and we were happy to play barefoot — that’s the way it was back then. “My father bought us a ball, a size 4. It wasn’t too big but it was fine. We would play at home and coming home from school a lot of people would come in playing with us, schoolboys, and often, very often, the Spanish would come in taking shelter from the weather, they would come in and play soccer with us. “If there was bad weather, they’d take shelter here in the harbour. They wouldn’t have a penny but a drop of wine in bags but they had no money and they’d come in and play. It was nice to watch them. I was practicing left and right but we had no trainers or coaches at the time. It was just a case of practicing between ourselves, nice and gently. There were no matches but games between ourselves and that’s all we had at the time.” It was O’Connell’s father Jeremiah who helped begin his son’s love of Gaelic football although he himself had no background in the game. “My own mother (Mary), she was never at a match and my uncle who was born in 1880 or that, he was living with us on Valentia Island, he was never at a match.“My father had an interest every now and again going to the matches. I remember them coming from Portmagee, Derrynane and Cahirciveen to play. That’s when I remember feeling that was something special about playing sport. “I remember going to a game on a boat with my father. The Islanders were playing, that was in 1945, and those memories from long ago come back to me every so often. And a lot of those players and a lot of the inter-county players are dead now. But I remember the first time I played in a Munster final in Killarney, in 1956, and only two of those players are still alive (Tom Long and Seán Ó Murchú).” But for a job in which he worked at for most of his Kerry playing days, O’Connell said he would never have worn the green and gold. “Between 1956 and ‘66, I worked for the Western Union company on Valentia Island, five full days and a half day on Saturday. It was a very useful job; it facilitated me in a great way. Otherwise, it was a job that would be too demanding and it also meant I was free at the weekends. “Any person playing amateur sport without an appropriate job would find it very hard to find perfection in it. Otherwise, I would never have played for Kerry.” O’Connell has questioned the Government’s grants scheme for inter-county Gaelic players. The Valentia Island man believes the funding mechanism, which will rise to €3 million per annum by 2018, has been signed off without the authority of the Irish tax-payers.Interviewed by Raidió na Gaeltachta on his 80th birthday yesterday, O’Connell criticised the Government for what he determines as directing remuneration towards county footballers and hurlers. “I have no involvement in the games today, except for watching it, but something I don’t agree with... it’s okay for the GAA to generate money in Croke Park and to spend it on the players if they want to, but I don’t agree at all that Government money, money of the Government of Ireland collected through taxes from the ordinary person, is being paid to the players. “I don’t think they have any permission to do that. That money should be spent on health and education rather than what’s being done now that I read in the paper, which is the way it is now.” In a wide-ranging interview with Helen Ní Shé on the An Saol ó Dheas programme, O’Connell also took a dim view of outgoing Kerry minor footballer Mark O’Connor’s switch to AFL club Geelong on a two-year rookie contract. “I’m not too impressed with that game in Australia at all. If Gaelic football was played properly, without pulling and dragging out of each other, and things like that, it would be a much better game than the game in Australia. “But again, in this country, the money isn’t in this country to give money to the players professionally at all and people have jobs now. If they had a good job and time to train, it’s a pastime. It’s a pastime. “Sport is a pastime. And people are saying there is pressure on them because they have to train... it’s a pastime for the trainer too, meeting and in contact with people the same age as them and things like that. That’s a great thing.” O’Connell doesn’t buy the idea more Gaelic players want to be involved in a full-time sport“Ah, that’s the kind of talk the media presents before them, that there is pressure on them. Give it up if you’re not happy, that’s the way it should be. To be good at anything, you enjoy anything that you’re good at, and practice that, you understand.” He marvels at what modern day players are provided with. “They have the facilities now. The facilities weren’t there long ago. But they have a lot of facilities now. Look at Fitzgerald Stadium in Killarney, there wasn’t a stand, there wasn’t a dressing room or anything when I started playing. As far as I remember, I don’t know what you called it, the mental hospital, we had a room in that place where we togged out. Every place throughout Kerry and throughout Ireland, the facilities are at a very high standard now in comparison to years ago.” Speaking to Jerry O’Sullivan on Radio Kerry’s Kerry Today programme, O’Connell bemoaned where Gaelic football was going and the negativity attached to it.“The (current) game doesn’t appeal to me. For me anyway it was always ball first, man second. To try and negate the other player it wasn’t my style.” O’Connell insisted he wasn’t criticising current players but the game itself and how it was taken too much from other codes. Although the mark has been championed as a means of safeguarding the high-fielding O’Connell was renowned for, he sees it as another example of a foreign rule. Even in my own time, there was no clear-cut set of rules stated in print for a referee. “I always thought as a player that a referee’s job should be almost to mark the scores and players playing the game should know what the game was and play accordingly.O’Connell continued: “Gaelic football has been played for about 120 years or whatever so and there is no bit of original wisdom within it to have your own game and to be powerful of your own game and not to be borrowing from other (sports), mark or no mark, red card, yellow card. It’s borrowing from other codes and that’s the negativity. It’s been always there, especially so now.” In an at times awkward conversation on Newstalk’s Off The Ball last night, O’Connell played down the significance of his sporting accomplishments. “Winning the game was not triumph and losing the game was not disaster. It was winning and losing games and that was all part of sport.” He remarked he had no passion in life. “Passion in life? None. None whatsoever. Playing football afforded me the chance to do exercise and play games locally and sometimes in Dublin. It was a nice way of associating with other people and so on. “It wasn’t a passion as such. Some people might think because living on an island (that it was) but it just happened that I occurred to be very good at it and got my place on the county team and got some games in Dublin.” He admitted his reluctance with the adulation he has received over the years. “That’s only comment. There’s no such thing as one player being better than the next because football is about a style of play. Some people have different styles and if one style satisfies some people other people might like the do-or-die effort. “Beloved? I don’t know what that means. If your style of play satisfies, all well and good but maybe I wasn’t ruthless enough. I wouldn’t do anything to win. The end to me wasn’t as important as the means. The means in which I played was a justification and if it won all well and good. “When I see people talking about Kerry beaten and a disastrous result, there is no such thing in the game of sport. Win or lose, you take your win or your beating in your stride, that’s it. “Another thing, coming from Valentia Island, I was kind of unique. Being an islander, it was unusual and that was why a lot of attention was put on me. It was difficult because you had difficult, bad weather sometimes here and you could never really practice to your extent. “That was often attributed to me, being in a kind of an unique and odd situation, that there must be something strange about a person to play from an island. It wasn’t. It was the game, the code of the area, and I played from an early age. “It wasn’t the be-all and end-all because in my household there was no discussion on football.” ‘Any day if I caught a few good balls and kicked a few good balls, that was success’ Mick O’Connell says the simple satisfaction of having “caught a few good balls and kicked a few good balls” is what remains with him most from his playing time with Kerry. Looking back, he doesn’t like to use the word “career” and when asked if the battles with the famed Galway of the 1960s were what come back to him most he replied: “I enjoyed all games whether it was here in Cahirsiveen, Tralee, Fitzgerald Stadium or New Ross, Tuam or any other place I was. “Any day if I caught a few good balls and kicked a few good balls that was success. “I played in 10 All-Irelands and lost a bigger percentage than I won (four victories). So be it, I had involvement. Success is a bit sweeter when you taste a bit of defeat as well. “That was my view. Looking back on it, it gave me a great association with people from different parts of Kerry and different parts of Ireland and abroad as well. Sport was a great dimension to my life but not everything.” O’Connell also returned to 1959 when he captained Kerry to an All-Ireland crown and left the Sam Maguire Cup in the dressing room. “I got the cup from Dr (Joseph) Stuart who was the president of the GAA at the time and my knee was injured the same day. I left the cup in the dressing room and I came home on the train and people asked me the reason I didn’t take the Sam Maguire with me. It was the team’s cup, I was no bigger than any other member of the team. The people who were in charge should have taken it home. It came home to the island a few weeks or so afterwards.”He doesn’t know the location of his four Celtic Crosses. “It doesn’t matter. I don’t know. I gave one of them to somebody. There was a raffle or something on years ago.”“The purpose of the game was to deliver it (the ball) as distinct from now when carrying the ball, running with it and passing with it. That’s the big change. I don’t blame the players at present. It’s very confusing. Even in my time, the elders never clearly stated a rule about obstruction or anything like that. It’s very hard in Ireland to get a discussion on the game.” -

Great aerial shot of packed to capacity Sample Stadium,Thurles for the specially staged 1984 All Ireland Hurling Final between Cork and Offaly. 35cm x 45cm. Thurles Co Tipperary The Semple Stadium is the home of hurling and Gaelic football for Tipperary GAA and for the province of Munster. Located in Thurles, County Tipperary, it is the second largest GAA stadium in Ireland (after Croke Park), with a capacity of 45,690. Over the decades since 1926, it has established itself as the leading venue for Munster hurling followers, hosting the Munster Hurling Final on many memorable occasions. The main or 'Old Stand' of the ground (also known as the 'Ardán Ó Coinneáin' or 'Dr Kinane Stand') lies across from the 'New Stand' (also known as the 'Ardán Ó Riáin') both of which are covered. Behind the goals are two uncovered terraces known as the 'Town End' (also known as the 'Davin Terrace') and the 'Killinan End' (also known as the 'Maher Terrace') respectively. Currently the stadium has a capacity of 45,690 of which 24,000 are seated.

Great aerial shot of packed to capacity Sample Stadium,Thurles for the specially staged 1984 All Ireland Hurling Final between Cork and Offaly. 35cm x 45cm. Thurles Co Tipperary The Semple Stadium is the home of hurling and Gaelic football for Tipperary GAA and for the province of Munster. Located in Thurles, County Tipperary, it is the second largest GAA stadium in Ireland (after Croke Park), with a capacity of 45,690. Over the decades since 1926, it has established itself as the leading venue for Munster hurling followers, hosting the Munster Hurling Final on many memorable occasions. The main or 'Old Stand' of the ground (also known as the 'Ardán Ó Coinneáin' or 'Dr Kinane Stand') lies across from the 'New Stand' (also known as the 'Ardán Ó Riáin') both of which are covered. Behind the goals are two uncovered terraces known as the 'Town End' (also known as the 'Davin Terrace') and the 'Killinan End' (also known as the 'Maher Terrace') respectively. Currently the stadium has a capacity of 45,690 of which 24,000 are seated.The Dome

The sports hall accommodates a full-sized basketball court suitable for national standard competition. The hall is also lined for badminton, volleyball, and indoor soccer. It is used in the evenings and weekends by the Tipperary hurling and football teams for training and on match days, the building is used to accommodate GAA and sponsor guests for corporate lunches and functions. It has also been used as a music venue.Future development

In July 2018 Tipperary County Board prepared to submit plans to Tipperary County Council to see the Kinnane stand redeveloped into a multi-purpose facility. The proposal would see the “Old Stand” as it is known to many, have a second level created over the concourse at the back of the stand. The half nearest the Killinan End terrace will be dedicated to players and will include a full-sized gym, physio room, stats/analysis room plus changing rooms and toilet facilities. The other half, towards the Sarsfields Centre side, would include a function room to accommodate up to 250 people, with adjoining bar and kitchen facility for catering. The development will also include a new corridor leading to a new VIP enclosure area in the Kinnane stand. The estimated cost of the project is €5 million. The planning application for the development was lodged with Tipperary County Council in April 2019. The planning application also includes reconfiguration of the seating area and modifications to the ground floor, including turnstiles, the construction of a new exit gate, and three service cores providing access to upper floor levels, which will include wheelchair-accessible turnstiles. Wilson Architecture in Cork was commissioned to help put together the planning application. Planning permission was granted in April 2020.History

The grounds on which Semple Stadium is built were formerly known as Thurles Sportsfield. The site was offered for sale in 1910 at the wish of Canon M.K. Ryanand was purchased by local Gaelic games enthusiasts for £900. To meet the cost of the purchase, an issue of shares was subscribed by the townspeople. The grounds remained in the hands of the shareholders until 1956 when they were transferred to the Gaelic Athletic Association. In 1934 in anticipation of the All-Ireland Hurling Final being held in the grounds to mark the golden jubilee of the Association, extensive improvements were made to bring the field requirements up to the demands which a crowd of up to 60,000 would make. The embankments around the field were raised and extended and the stand accommodation was also extended. However, the jubilee final was held in Croke Park and it was another 50 years before the Stadium would host the long-awaited All-Ireland final as a showpiece to mark the centenary. In 1968 further developments took place when the Dr. Kinane Stand was completed and opened. In 1971 the stadium was named after Tom Semple, famed captain of the Thurles "Blues". He won All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship medals in 1900, 1906 and 1908. The Ardán Ó Riáin opposite the Kinane Stand and the terracing at the town end of the field were completed in 1981 at a cost of £500,000. This development and the terracing at the Killinan end of the field were part of a major improvement scheme for the celebration of the centenary All-Ireland Hurling Final between Cork and Offaly in 1984. Dublin v Kerry in the quarter-finals of the 2001 All-Ireland Senior Football Championship was held at Semple Stadium. In April 2006 Tipperary County Board announced an €18 million redevelopment plan for the Stadium. The three-year project aimed to boost capacity to over 55,000, as well as providing a wide range of modern facilities such as corporate space concessions, dining and changing areas within both main stands. There were also plans to upgrade the standing terraces and install a modern floodlighting facility. Phase one of the upgrade project, upgrading the Kinnane Stand side of the stadium, involved expenditure of €5.5 million. On 14 February 2009 the new state of the art floodlights were switched on by GAA President Nickey Brennan before the National Hurling League game against Cork. In 2016, Hawk-Eye was installed in the stadium and used for the first time during the Munster Championship quarter-final between Tipperary and Cork. An architectural consultancy has been appointed to lead a design team, tasked with preparing a master plan for the redevelopment of Semple Stadium.Music festival

The Féile Festival, ran from 1990 to 1994 (and returned in 1997 for one day), was held at Semple Stadium. At the height of its success, an estimated 150,000 people attended the festival, which was also known as "The Trip to Tipp". Irish and international artists participated, including The Prodigy, The Cranberries, Blur, Bryan Adams, Van Morrison, Rage Against the Machine, The Saw Doctors and Christy Moore. The Féile Classical Concerts took place at Semple Stadium in September 2018. Line up included Irish musical acts that played in the 1990s at the Féile festivals. Named as Tipp Classical, it will return in September 2019. -

7Vintage advert for the 4 and 3 Seater Chevrolet (Agent ;The North Tipperary Motor Company P Flannery 6 & 7 McDonagh St Nenagh Co Tipperary).The 4 seater delivered complete cost £210 with the 3 seater English Body costing a heftier £280. 33cm x 44cm Nenagh Co Tipperary In November 3, 1911, Swiss race car driver and automotive engineer Louis Chevrolet co-founded the "Chevrolet Motor Company" in Detroit with William C. Durant and investment partners William Little (maker of the Little automobile), former Buick owner James H. Whiting,[6] Dr. Edwin R. Campbell (son-in-law of Durant) and in 1912 R. S. McLaughlin CEO of General Motors in Canada. Durant was cast out from the management of General Motors in 1910, a company which he had founded in 1908. In 1904 he had taken over the Flint Wagon Works and Buick Motor Company of Flint, Michigan. He also incorporated the Mason and Little companies. As head of Buick, Durant had hired Louis Chevrolet to drive Buicks in promotional races. Durant planned to use Chevrolet's reputation as a racer as the foundation for his new automobile company. The first factory location was in Flint, Michigan at the corner of Wilcox and Kearsley Street, now known as "Chevy Commons" at coordinates 43.00863°N 83.70991°W, along the Flint River, across the street from Kettering University. Actual design work for the first Chevy, the costly Series C Classic Six, was drawn up by Etienne Planche, following instructions from Louis. The first C prototype was ready months before Chevrolet was actually incorporated. However the first actual production wasn't until the 1913 model. So in essence there were no 1911 or 1912 production models, only the 1 pre-production model was made and fine tuned throughout the early part of 1912. Then in the fall of that year the new 1913 model was introduced at the New York auto show.Chevrolet first used the "bowtie emblem" logo in 1914 on the H series models (Royal Mail and Baby Grand) and The L Series Model (Light Six). It may have been designed from wallpaper Durant once saw in a French hotel room.More recent research by historian Ken Kaufmann presents a case that the logo is based on a logo of the "Coalettes" coal company.[10][11] An example of this logo as it appeared in an advertisement for Coalettes appeared in the Atlanta Constitution on November 12, 1911.Others claim that the design was a stylized Swiss cross, in tribute to the homeland of Chevrolet's parents. Over time, Chevrolet would use several different iterations of the bowtie logo at the same time, often using blue for passenger cars, gold for trucks, and an outline (often in red) for cars that had performance packages. Chevrolet eventually unified all vehicle models with the gold bowtie in 2004, for both brand cohesion as well as to differentiate itself from Ford (with its blue oval logo) and Toyota (who has often used red for its imaging), its two primary domestic rivals. Louis Chevrolet had differences with Durant over design and in 1914 sold Durant his share in the company. By 1916, Chevrolet was profitable enough with successful sales of the cheaper Series 490 to allow Durant to repurchase a controlling interest in General Motors. After the deal was completed in 1917, Durant became president of General Motors, and Chevrolet was merged into GM as a separate division. In 1919, Chevrolet's factories were located at Flint, Michigan; branch assembly locations were sited in Tarrytown, N.Y., Norwood, Ohio, St. Louis, Missouri, Oakland, California, Ft. Worth, Texas, and Oshawa, Ontario General Motors of Canada Limited. McLaughlin's were given GM Corporation stock for the proprietorship of their Company article September 23, 1933 Financial Post page 9.In the 1918 model year, Chevrolet introduced the Series D, a V8-powered model in four-passenger roadster and five-passenger tourer models. Sales were poor and it was dropped in 1919. Beginning also in 1919, GMC commercial grade trucks were rebranded as Chevrolet, and using the same chassis of Chevrolet passenger cars and building light-duty trucks. GMC commercial grade trucks were also rebranded as Chevrolet commercial grade trucks, sharing an almost identical appearance with GMC products.

7Vintage advert for the 4 and 3 Seater Chevrolet (Agent ;The North Tipperary Motor Company P Flannery 6 & 7 McDonagh St Nenagh Co Tipperary).The 4 seater delivered complete cost £210 with the 3 seater English Body costing a heftier £280. 33cm x 44cm Nenagh Co Tipperary In November 3, 1911, Swiss race car driver and automotive engineer Louis Chevrolet co-founded the "Chevrolet Motor Company" in Detroit with William C. Durant and investment partners William Little (maker of the Little automobile), former Buick owner James H. Whiting,[6] Dr. Edwin R. Campbell (son-in-law of Durant) and in 1912 R. S. McLaughlin CEO of General Motors in Canada. Durant was cast out from the management of General Motors in 1910, a company which he had founded in 1908. In 1904 he had taken over the Flint Wagon Works and Buick Motor Company of Flint, Michigan. He also incorporated the Mason and Little companies. As head of Buick, Durant had hired Louis Chevrolet to drive Buicks in promotional races. Durant planned to use Chevrolet's reputation as a racer as the foundation for his new automobile company. The first factory location was in Flint, Michigan at the corner of Wilcox and Kearsley Street, now known as "Chevy Commons" at coordinates 43.00863°N 83.70991°W, along the Flint River, across the street from Kettering University. Actual design work for the first Chevy, the costly Series C Classic Six, was drawn up by Etienne Planche, following instructions from Louis. The first C prototype was ready months before Chevrolet was actually incorporated. However the first actual production wasn't until the 1913 model. So in essence there were no 1911 or 1912 production models, only the 1 pre-production model was made and fine tuned throughout the early part of 1912. Then in the fall of that year the new 1913 model was introduced at the New York auto show.Chevrolet first used the "bowtie emblem" logo in 1914 on the H series models (Royal Mail and Baby Grand) and The L Series Model (Light Six). It may have been designed from wallpaper Durant once saw in a French hotel room.More recent research by historian Ken Kaufmann presents a case that the logo is based on a logo of the "Coalettes" coal company.[10][11] An example of this logo as it appeared in an advertisement for Coalettes appeared in the Atlanta Constitution on November 12, 1911.Others claim that the design was a stylized Swiss cross, in tribute to the homeland of Chevrolet's parents. Over time, Chevrolet would use several different iterations of the bowtie logo at the same time, often using blue for passenger cars, gold for trucks, and an outline (often in red) for cars that had performance packages. Chevrolet eventually unified all vehicle models with the gold bowtie in 2004, for both brand cohesion as well as to differentiate itself from Ford (with its blue oval logo) and Toyota (who has often used red for its imaging), its two primary domestic rivals. Louis Chevrolet had differences with Durant over design and in 1914 sold Durant his share in the company. By 1916, Chevrolet was profitable enough with successful sales of the cheaper Series 490 to allow Durant to repurchase a controlling interest in General Motors. After the deal was completed in 1917, Durant became president of General Motors, and Chevrolet was merged into GM as a separate division. In 1919, Chevrolet's factories were located at Flint, Michigan; branch assembly locations were sited in Tarrytown, N.Y., Norwood, Ohio, St. Louis, Missouri, Oakland, California, Ft. Worth, Texas, and Oshawa, Ontario General Motors of Canada Limited. McLaughlin's were given GM Corporation stock for the proprietorship of their Company article September 23, 1933 Financial Post page 9.In the 1918 model year, Chevrolet introduced the Series D, a V8-powered model in four-passenger roadster and five-passenger tourer models. Sales were poor and it was dropped in 1919. Beginning also in 1919, GMC commercial grade trucks were rebranded as Chevrolet, and using the same chassis of Chevrolet passenger cars and building light-duty trucks. GMC commercial grade trucks were also rebranded as Chevrolet commercial grade trucks, sharing an almost identical appearance with GMC products. Chevrolet plant in Tarrytown, NY, c. 1918Chevrolet continued into the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s competing with Ford, and after the Chrysler Corporation formed Plymouth in 1928, Plymouth, Ford, and Chevrolet were known as the "Low-priced three".[16] In 1929 they introduced the famous "Stovebolt" overhead-valve inline six-cylinder engine, giving Chevrolet a marketing edge over Ford, which was still offering a lone flathead four ("A Six at the price of a Four"). In 1933 Chevrolet launched the Standard Six, which was advertised in the United States as the cheapest six-cylinder car on sale.[17] Chevrolet had a great influence on the American automobile market during the 1950s and 1960s. In 1953 it produced the Corvette, a two-seater sports car with a fiberglass body. In 1957 Chevy introduced its first fuel injected engine,[18] the Rochester Ramjet option on Corvette and passenger cars, priced at $484.[19] In 1960 it introduced the Corvair, with a rear-mounted air-cooled engine. In 1963 one out of every ten cars sold in the United States was a Chevrolet.[20]

Chevrolet plant in Tarrytown, NY, c. 1918Chevrolet continued into the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s competing with Ford, and after the Chrysler Corporation formed Plymouth in 1928, Plymouth, Ford, and Chevrolet were known as the "Low-priced three".[16] In 1929 they introduced the famous "Stovebolt" overhead-valve inline six-cylinder engine, giving Chevrolet a marketing edge over Ford, which was still offering a lone flathead four ("A Six at the price of a Four"). In 1933 Chevrolet launched the Standard Six, which was advertised in the United States as the cheapest six-cylinder car on sale.[17] Chevrolet had a great influence on the American automobile market during the 1950s and 1960s. In 1953 it produced the Corvette, a two-seater sports car with a fiberglass body. In 1957 Chevy introduced its first fuel injected engine,[18] the Rochester Ramjet option on Corvette and passenger cars, priced at $484.[19] In 1960 it introduced the Corvair, with a rear-mounted air-cooled engine. In 1963 one out of every ten cars sold in the United States was a Chevrolet.[20] -

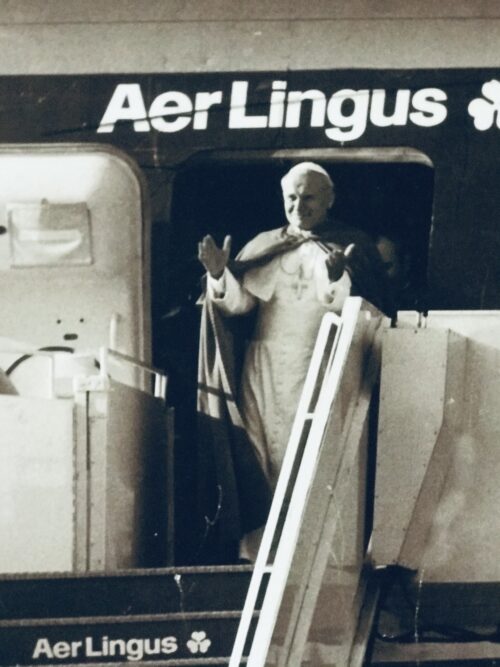

Nostalgic,atmospheric photo of Pope John Paul II arriving at Dublin Airport in 1979 on board an Aer Lingus 747-it was the first time a Pope had visited Ireland . 66cm x 56cm Gort Co Galway Pope John Paul visited Ireland from Saturday 29 September to Monday, 1 October 1979, the first trip to Ireland by a pope. Over 2.5 million people attended events in Dublin, Drogheda, Clonmacnoise, Galway, Knock, Limerick, and Maynooth. It was one of John Paul's first foreign visits as Pope, who had been elected in October 1978. The visit marked the centenary of the reputed apparitions at the Shrine of Knock in August 1 1878. An Aer Lingus Boeing 747, named St Patrick, brought Pope John Paul II from Rome to Dublin Airport. The Pope kissed the ground as he disembarked. After being greeted by the President of Ireland Patrick Hillery, the Pope flew by helicopter to Phoenix Park where he celebrated Mass for 1,250,000 people, one third of the population of the Republic of Ireland. Afterwards he travelled to Killineer, near Drogheda, where he led a Liturgy of the Word for 300,000 people, many from Northern Ireland. There the Pope appealed to the men of violence: "on my knees I beg you to turn away from the path of violence and return to the ways of peace". The Pope had hoped to visit Armagh, but the security situation in Northern Ireland rendered it impossible. Drogheda was selected as an alternative venue as it is situated in the Catholic Archdiocese of Armagh. Returning to Dublin that evening, the Pope was greeted by 750,000 people as he travelled in an open top popemobile through the city centre and visited Áras an Uachtaráin, the residence of the Irish President.His final engagement was a meeting with journalists at the Dominican Convent in Cabra.The journalists from the international media broke into a spontaneous rendition of 'For he's a jolly good fellow' when the Pope arrived. Pope John Paul spent the night at the nearby Apostolic Nunciature on the Navan Road in Cabra. Pope John Paul began the second day of his tour with a short visit to the ancient monastery at Clonmacnoise in County Offaly.With 20,000 in attendance, he spoke of how the ruins were "still charged with a great mission".Later that morning he celebrated a Youth Mass for 300,000 at Ballybrit Racecourse in Galway. It was here that the Pope uttered perhaps the most memorable line of his visit: "Young people of Ireland, I love you".That afternoon, he travelled by helicopter to Knock Shrine in County Mayo which he described as "the goal of my journey to Ireland".The outdoor Mass at the shrine was attended by 450,000. The Pope met with the sick and elevated the church to the title of Basilica. He lit a candle at the Gable Wall for the families of Ireland. Monsignor James Horan, instrumental in the shrine's development, welcomed the Pope to Knock. The final day of the visit began with a brief early morning visit to St Patrick's College, Maynooth, the National Seminary, in County Kildare.Some 80,000 people joined 1,000 seminarians on the grounds of the college for the brief visit. A dense fog delayed the Pope's arrival from Dublin by helicopter. The final Mass of the Pope's visit to Ireland was celebrated at Greenpark Racecoursein Limerick before 400,000 people, many more than had been expected. The Mass was offered for the people of Munster. Pope John Paul left Ireland from nearby Shannon Airport travelling to Boston where he began a six-day tour of the United States. Pope John Paul delivered 22 homilies and addresses during the course of this visit, including a televised message for the sick broadcast on RTÉ on the evening of his arrival in Ireland. Audio files of his more significant speeches are preserved on the website of the Irish Catholic Bishops Conference.Many of the temporary fixtures and ornaments at the public masses were auctioned two months after the visit to help defray its cost. A Time Remembered - The Visit of Pope John Paul II to Ireland was produced by RTÉ in 2005. Many children were named John and Paul in the aftermath of the papal visit. There were many Johns and Pauls beforehand but there was a huge increase in the amount of children called after the Pope's taken names. Some children were also given both names as their Christian name and were known as John Paul in honour of the Pope's visit.

Nostalgic,atmospheric photo of Pope John Paul II arriving at Dublin Airport in 1979 on board an Aer Lingus 747-it was the first time a Pope had visited Ireland . 66cm x 56cm Gort Co Galway Pope John Paul visited Ireland from Saturday 29 September to Monday, 1 October 1979, the first trip to Ireland by a pope. Over 2.5 million people attended events in Dublin, Drogheda, Clonmacnoise, Galway, Knock, Limerick, and Maynooth. It was one of John Paul's first foreign visits as Pope, who had been elected in October 1978. The visit marked the centenary of the reputed apparitions at the Shrine of Knock in August 1 1878. An Aer Lingus Boeing 747, named St Patrick, brought Pope John Paul II from Rome to Dublin Airport. The Pope kissed the ground as he disembarked. After being greeted by the President of Ireland Patrick Hillery, the Pope flew by helicopter to Phoenix Park where he celebrated Mass for 1,250,000 people, one third of the population of the Republic of Ireland. Afterwards he travelled to Killineer, near Drogheda, where he led a Liturgy of the Word for 300,000 people, many from Northern Ireland. There the Pope appealed to the men of violence: "on my knees I beg you to turn away from the path of violence and return to the ways of peace". The Pope had hoped to visit Armagh, but the security situation in Northern Ireland rendered it impossible. Drogheda was selected as an alternative venue as it is situated in the Catholic Archdiocese of Armagh. Returning to Dublin that evening, the Pope was greeted by 750,000 people as he travelled in an open top popemobile through the city centre and visited Áras an Uachtaráin, the residence of the Irish President.His final engagement was a meeting with journalists at the Dominican Convent in Cabra.The journalists from the international media broke into a spontaneous rendition of 'For he's a jolly good fellow' when the Pope arrived. Pope John Paul spent the night at the nearby Apostolic Nunciature on the Navan Road in Cabra. Pope John Paul began the second day of his tour with a short visit to the ancient monastery at Clonmacnoise in County Offaly.With 20,000 in attendance, he spoke of how the ruins were "still charged with a great mission".Later that morning he celebrated a Youth Mass for 300,000 at Ballybrit Racecourse in Galway. It was here that the Pope uttered perhaps the most memorable line of his visit: "Young people of Ireland, I love you".That afternoon, he travelled by helicopter to Knock Shrine in County Mayo which he described as "the goal of my journey to Ireland".The outdoor Mass at the shrine was attended by 450,000. The Pope met with the sick and elevated the church to the title of Basilica. He lit a candle at the Gable Wall for the families of Ireland. Monsignor James Horan, instrumental in the shrine's development, welcomed the Pope to Knock. The final day of the visit began with a brief early morning visit to St Patrick's College, Maynooth, the National Seminary, in County Kildare.Some 80,000 people joined 1,000 seminarians on the grounds of the college for the brief visit. A dense fog delayed the Pope's arrival from Dublin by helicopter. The final Mass of the Pope's visit to Ireland was celebrated at Greenpark Racecoursein Limerick before 400,000 people, many more than had been expected. The Mass was offered for the people of Munster. Pope John Paul left Ireland from nearby Shannon Airport travelling to Boston where he began a six-day tour of the United States. Pope John Paul delivered 22 homilies and addresses during the course of this visit, including a televised message for the sick broadcast on RTÉ on the evening of his arrival in Ireland. Audio files of his more significant speeches are preserved on the website of the Irish Catholic Bishops Conference.Many of the temporary fixtures and ornaments at the public masses were auctioned two months after the visit to help defray its cost. A Time Remembered - The Visit of Pope John Paul II to Ireland was produced by RTÉ in 2005. Many children were named John and Paul in the aftermath of the papal visit. There were many Johns and Pauls beforehand but there was a huge increase in the amount of children called after the Pope's taken names. Some children were also given both names as their Christian name and were known as John Paul in honour of the Pope's visit. -

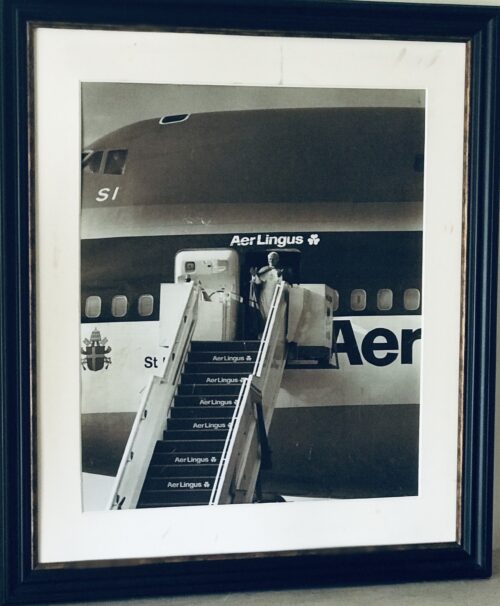

On this day in 1963 JFK came to Ireland - What his historic trip meant to him and his ancestral home.

On this day (June 25) 1963, President John F. Kennedy arrived in Ireland on an emotional trip to his ancestral home. His speech is remembered for quoting the text of a Sinéad de Valera poem.

In June 1963, just five months before his assassination in Dallas, President John F. Kennedy made his historic trip to Ireland. On his last night in Ireland Kennedy was the guest of President de Valera and his wife Sinéad. Sinéad de Valera was an accomplished Irish writer, folklorist, and poet. During the evening she recited a poem of exile for the young president who was so impressed that he wrote it down on his place card. Over breakfast the next day, JFK memorized the poem and recited it in his last speech at Shannon as he departed.It reads: "'Tis the Shannon's brightly glancing stream, brightly gleaming, silent in the morning beam. Oh! the sight entrancing. Thus return from travels long, years of exile, years of pain to see Old Shannon's face again, O'er the waters glancing." Then he said, "Well, I am going to come back and see Old Shannon's face again, and I am taking, as I go back to America, all of you with me." Jackie Kennedy could not accompany her husband due to a difficult pregnancy with Patrick, her son who died soon after birth. Kennedy himself was suffering from physical stress and illness, a back condition and Addison's Disease to name but -two, but the vibrant face he showed to the world in Ireland would always be the lasting impression.Of course, he would never return to Ireland, struck down by an assassin's bullet 53 years ago. Yet, with each passing president, the JFK legend seems to grow larger. His popularity in America in the summer of 1963, just two and a half years into his presidency, seemed to make him a certainty for re-election. When he took his Irish trip, his approval rating was at an incredible 82 percent (Donald Trump is 45 percent at the moment; President Obama 63 percent) surpassing any president in history in a non-war situation. Kennedy was growing in stature, having faced down the Russians over Cuba, promising a man on the moon by 1970, and completing an amazing trip to Berlin where his speech “Ich Bin Ein Berliner” inspired a generation of separated Germans to come together again some 25-years later. Yet we will never know the full measure of the man. Two of his closest associates, Dave Powers and Kenneth O’Donnell, wrote a biography of Kennedy and entitled "Johnny We Hardly Knew You."President John F. Kennedy addresses a crowd at Redmond Place in Co. Wexford.

The title was taken from a sign someone held up when Kennedy was driving to Co. Wexford on his visit to his homestead. In 2013, the New Ross museum dedicated to Kennedy discovered the identity of the man holding up the sign and retrieved the sign for the museum. As sung by the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, “Johnny We Hardly Knew You” is a fierce anti-war song which portrays an old lover meeting her former lover after he had fought in the Great War and was severely injured. He is now a cripple begging on the street. Here are some of the lyrics: “With your drums and guns and drums and guns, the enemy nearly slew ye, oh my darling dear, ye look so queer (strange). Johnny I hardly knew ye.” Ironically, of course, John F. Kennedy would have his own life cut short, suffering horrific injuries from an assassin's bullets just five months after the glorious Irish trip.He would never see 'Old Shannon’s' face again, but also he would never be forgotten by those who witnessed his visit.The emigrant and exile had returned home to a tiny country that revered and loved him. He was their stepping stone to the 21st century, but his own dreams died just months later. May he rest in peace. -

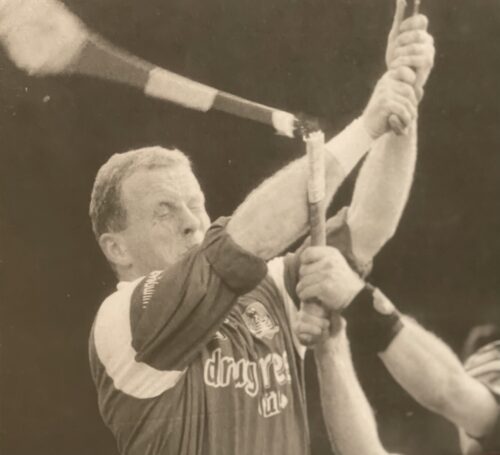

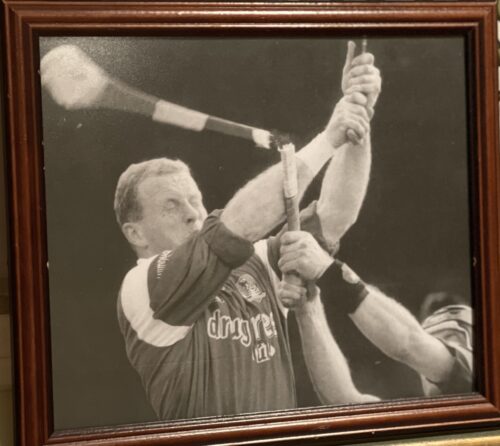

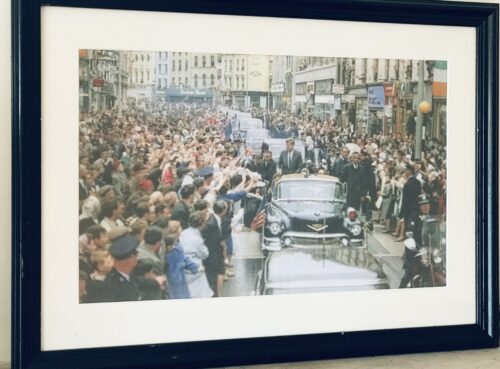

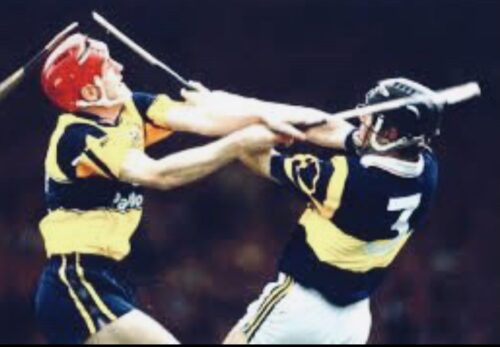

35cm x 45cm Cashel Co Tipperary Classic photograph depicting the physicality of the game of Hurling,Irelands national obsession as the ash Hurley is broken in two after colliding with the opposing players helmet as traditional rivals Clare and Tipperary battle for supremacy at Semple Stadium Thurles.

35cm x 45cm Cashel Co Tipperary Classic photograph depicting the physicality of the game of Hurling,Irelands national obsession as the ash Hurley is broken in two after colliding with the opposing players helmet as traditional rivals Clare and Tipperary battle for supremacy at Semple Stadium Thurles. -

16cm x 25cm. Dublin

16cm x 25cm. DublinHOLDING OF THE THIN GREEN LINE – UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN BOAT CLUB & THE 1948 OLYMPIC GAMES

BY MORGAN MCELLIGOTT

“Telegram for you, Professor.” The year was 1948 in Mooney’s of the Strand. Jim read “Flight delayed, cannot make Mooney’s, see you at Henley- on – Thames signed Holly.” Apparently the barman was transferred from the Dublin premises near Independent House to London and recognised his erstwhile customer, Jim Meenan. “Holly” was a sobriquet for J.J.E. Holloway, representative of the Leinster branch of the Irish Amateur Rowing Union (I.A.R.U.) and to the Federation Internationale des Societes d’Aviron (F.I.S.A.). The former was secretary and later President of the union. Both were officers of Old Collegians Boat Club (O.C.B.C.) and members of the emergency committee to deal with the Irish Olympic eight-oar crew entry and were hugely involved with the development of U.C.D. rowing. The Club founded in 1918, assumed significance in the thirties and peaked in 1939 by winning the intervarsity Wylie Cup and the Irish Senior and Junior Rowing Championships, coached by Holly and captained by Dermot Pierce, brother of Denis Sugrue.1947-1948

After some lean years, the College aimed at revivification under the author’s captaincy, by intensive training twice daily in 1947, repeating the above wins and making a significant inaugural appearance at the Royal Henley Regatta by beating Reading University and Kings College London in the initial rounds in the Thames Cup before elimination in the semi-final by the eventual winners, Kent School U.S.A. It was easy to predict the outcome of the 1948 season which, captained by Paddy Dooley, repeated the above Irish competitive season, finishing by victory in the final of the Irish Senior Eights Championship over Belfast Commercial Boat Club, at present Belfast Rowing Club, on the river Lagan.

CREW SELECTED

The I.A.R.U. had ruled previously that the winning eight would be nominated as an All- Ireland entry to the Olympic Games and the relevant sub-committee met immediately after the race on the 10th July 1948 and U.C.D. were invited to form the Olympic Crew. Dominant advice was given and accepted fully from Ray Hickey, who rowed in the successful Senior Championship eight in 1940 and coached both 1947 and 1948 crews. Initial practice was on the 12th and the crew was finally selected on the 16th July as follows:-Bow

T.G. Dowdall

UCD

2E.M.A McElligott

UCD

3J. Hanly

UCD

4D.D.B. Taylor

Queen’s

5B. McDonnell

UCD

6P.D.R. Harold

Neptune

7R.W.R Tamplin

Trinity

StrokeP.O. Dooley

UCD

CoxD.L. Sugrue

UCD

Coaches

R.G. Hickey

UCD

M. Horan

Trinity

Manager

D.S.F. O’Leary

UCD

Substitutes

H.R. Chantler

Trinity

W. Stevens

Neptune

EIRE/IRELAND-26/32

So far it seemed simple, but now it was the Eire/Ireland question; briefly, “Eire” meant pick your athletes from twenty-six counties, whereas “Ireland”‘ meant thirty-two counties. Dan Taylor, Captain of the Q.U.B.C. was included and the I.A.R.U. was not yet a member of the F.I.S.A. Some seventeen days of training followed on both Liffey and Thames. Long mileage was the hallmark of the college crews in the previous two seasons and included an indelibly remembered row from Islandbridge to Poolbeg Lighthouse on a calm day, it was subsequently learned that the U.S.A. and Norway, gold and bronze medal winners, crewed for two years and nine months respectively.BORDERLINE CONSEQUENCES

But more important matters were imminent in Henley-on-Thames Town Hall, such as, “Can we row Danny from Queens, Belfast? ” John Pius Boland, of Boland’s Bread and a law graduate of Balliol College Oxford, was a commissioner under the Irish Universities Act and named the new establishment the National University of Ireland. Earlier, in 1896, after winning two gold medals for tennis in the first Olympic Games of the modern era, he caused some upset when he demanded an Irish flag. Subsequent to the establishment of the twenty-six country Irish Free State, the question of Olympic entry from a thirty-two county Ireland was debated and re-affirmed at four international Olympic committee meetings ranging from Paris in 1924 to Berlin in 1930. In 1932, Bob Tisdall, 400 meters hurdle and Pat O’Callaghan, hammer, won gold medals; the thirty-two county status was thought to be ensured in spite of persistent objections by British, representatives, which were constantly over-ruled until 1934. In context, Sean Lavan of U.C.D. achieved first and second places in various heats of 200 and 400 meters in 1924 and 1928.ORATIO RECTA 1948 dialectic included: –

BOADICEA: Conqueror of Italians: “Eire is on your stamps and on your Department of External Affairs note paper.” MACHA: war Goddess of Ulster: “Yes, and you have Helvetia on your stamps and Switzerland on your note paper.” BOADICEA: “Eirelevant! And note the spelling, if you’ve graduated from Ogham. Your swimmers are already barred because of the inclusion of Northern Ireland competitors.” MACHA: “A jarvey’s arrogance, why, you have four competitors, born in southern Ireland including Chris Barton from Kildare, who stroked the British eight, winning a silver medal. Being rather proud of our athletic exports, we never raised the issue.” BOADICEA: “Verdant remarks from a verdant person, and how about Danny Boy from Queen’s University Boat Club.” MACHA: “Well, he is entitled to British and Irish passports and that reminds me of your performance of an Irish melody, the Londonderry Air which concerns my fief. BOADICEA: “Your Kevin Myers states you cannot be “Ireland” without a referendum.” MACHA: “Anachronisms are unacceptable and on your next raid on Londinium ask the king’s equerry why he introduced my friends as “Ireland” at the Buckingham Palace tea-party”.

FAULTY TOWERS

The twin towers of Wembley stadium came into view, we were going on parade with increased confidence in our entry, while the swimmers returned to Eire/Ireland. As we took our place, it appeared that the parade sign-board was Eire rather than Ireland. A rather polemic discussion ensued between the assistant Chief Marshal and Comdt. J.F. Chisholm, the Irish Chef de Mission; the latter pointed out that our entry was submitted and accepted as “Ireland” as the English language was mandatory in context e.g. Espana marched as Spain. The Marshal’s convincing riposte was that he always wrote “Eire” when writing to his Irish brother-in-law and that P. agus T. delivered accurately; this was followed by an awesome threat to trap us in the tunnel.

CORK’S CREWMANSHIP

The ebullient Donal S.F. O Leary, who rowed in the successful 1947 Wylie Cup senior eight, with Alphie Walshe, and, at present, our team manager assessed instantly the situation and when we were directed to march in line after Iraq, declared forcibly that there were thousands of Irish, or was it Eirish, people in the stands ready to cheer their team and wouldn’t it be an huge disappointment if we failed to march, on a matter of neology.

ON STREAM

In a temperature 90 F, with 58 nations, we marched as “Eire,” saluted King GeorgeVl, were cheered loudly by our own and by countries like India which recently gained independence, as we worried about losing a day’s practice on the water. The words of the visionary Pierre Baron de Coubertin, who revived the Olympic Games in 1896 after a lapse of some 1600 years, dominated the stadium:

THE IMPORTANT THING IN THE OLYMPIC GAMES IS NOT WINNING BUT TAKING PART. THE ESSENTIAL THING IN LIFE IS NOT CONQUERING BUT FIGHTING WELL

The Olympic torch, carried through a peaceful Europe, arrived and the Olympic flame was lit by Cambridge athlete, John Mark. Donald Finlay, former Olympic hurdler swore the oath. The King proclaimed the games open, Sir Malcolm Sergent, of the Albert Hall promenade concerts, conducted the orchestra with guards massed bands and choir in a stirring performance of the Londonderry Air; thousands of pigeons were released to carry messages of peace to countries of the world.UP STREAMBut upstream to Henley, the thirty-two county body I.A.R.U., represented by its President M.V. Rowan of Neptune R.C. and J.J.E. Holloway O.C.B.C., was elected unanimously to F.I.S.A. and was therefore the first athletic unit recognised as an all Ireland body at the XIV Olympiad. A laudable photo-finish as competition started on the morrow and it’s worth mentioning that, in contrast to current debatable practice, Irish rowing officials disclaimed all expenses.

LADIES LAST AND FIRST

A liberal proposal by eastern European countries “on the organisation of feminine championships received scant attention”. An Antipodean delegate stated that in his opinion: “Rowing, as a sport had sufficient complications without adding the feminine element thereto”. In a recent season Antipodean values, not delegates, prevailed in U.C.D. Ladies Boat Club captained by Oonagh Clarke; wins of their Senior Eight included Ghent International Regatta and Henley Regatta, beating Temple University U.S.A. in the final – a glorious season for the “feminine element”.THIN GREEN LINE

During all this induction, practice continued on the water. Most of the crew thought pragmatically that as long as we rowed all else was irrelevant. Heart or head, to be conservative at twenty is to have no heart, to be socialist at forty is to have no head. Initially some of our training was alongside the British crew, whom we could beat transiently off the starting stake-boat; the objection of other crews ended this liaison. Our exercise times over parts of the course proved favourably and superior to some of our competitors but on the day we were beaten in our heat by Canada and Portugal and the repechage by Norway. To quote Michael Johnston in his totally comprehensive book on Senior Championship rowing, entitled “The Big Pot”:- “They lost their races but held the Thin Green Line and brought Ireland into the world of real international rowing for the first time. “MEMORIA

Joe Hanly and Barry McDonnell were both heavy weights on the 1947 and 1948 championship crews, and subsequently Presidents of O.C.B.C. Joe was also Vice-Captain of U.C.D.B.C. in 1947. Barry died in 1976 and Joe in 1996. The sympathy of all U.C.D. Oarsmen was extended to their wives, Helen who was Inaugural President of U.C.D.B.C. Ladies, and Jane, respectively. In 1997 Joe was honoured posthumously in the presence of Jane and Dr. Art Cosgrove, President U.C.D., by naming a new fine VIII boat, “Joe Hanly” in the presence of Barry Doyle, President U.C.D.B.C. RESURRECTI SUMUSIn 1998 the 1948 Olympic crew were honoured in the presence of some 170 crews competing in the Irish National Rowing Championships. Inscribed trophies and pennants were presented by Tom Fennessy, President of the I.A.R.U. and Michael Johnston, in his citation, stressed how the crew ensured thirty-two county representation by holding the Thin Green Line.

Similarly, twenty-five contestants, out of a total ninety-one who competed in 1948, attended a reception hosted by the Irish Olympic Council. Trophies were presented and citations declared by Patrick Hickey. President of the Council. Speeches included that of Dave Guiney, National Irish Shop-Putting Champion, who spoke for the recipients, and Dr. Kevin O’Flanagan who received a special presentation for his medical services to the Games. During his student days at U.C.D. in the 1940’s, O’Flanagan developed a career which included winning National Championships for Sprinting, playing International Soccer and Rugby for Ireland. -

Out of stock

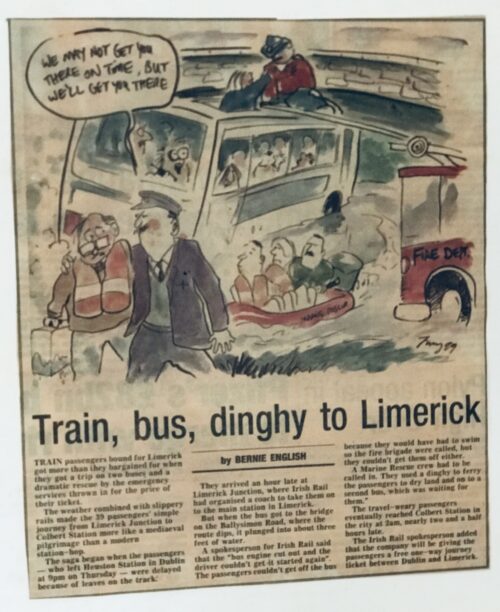

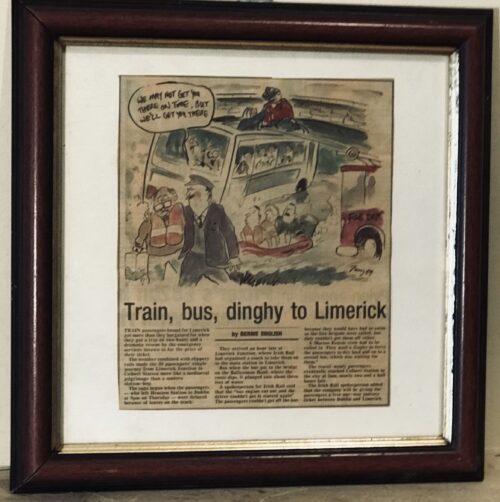

There’s almost a John Hughes film starting Steve Martin & John Candy to be made about this particularly protracted journey from to Limerick ! Another in our series of humorous excerpts from Irish provincial newspapers or colloquially known as 'bog cuttings' in Phoenix Magazine. Origins :Limerick. Dimensions : 30cm x 30cm

There’s almost a John Hughes film starting Steve Martin & John Candy to be made about this particularly protracted journey from to Limerick ! Another in our series of humorous excerpts from Irish provincial newspapers or colloquially known as 'bog cuttings' in Phoenix Magazine. Origins :Limerick. Dimensions : 30cm x 30cm -

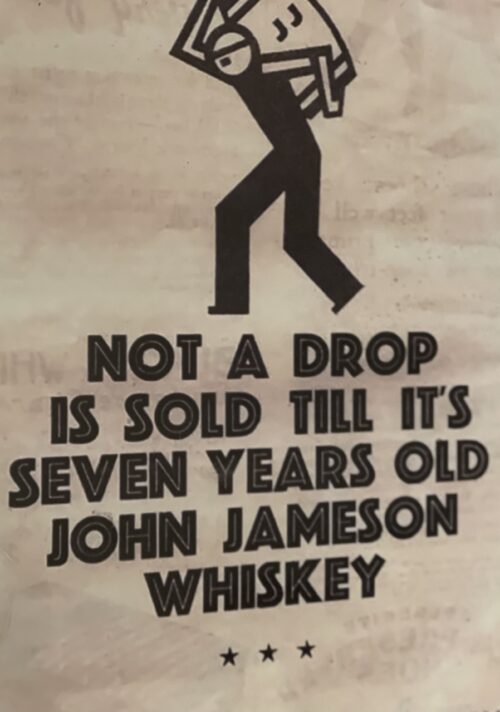

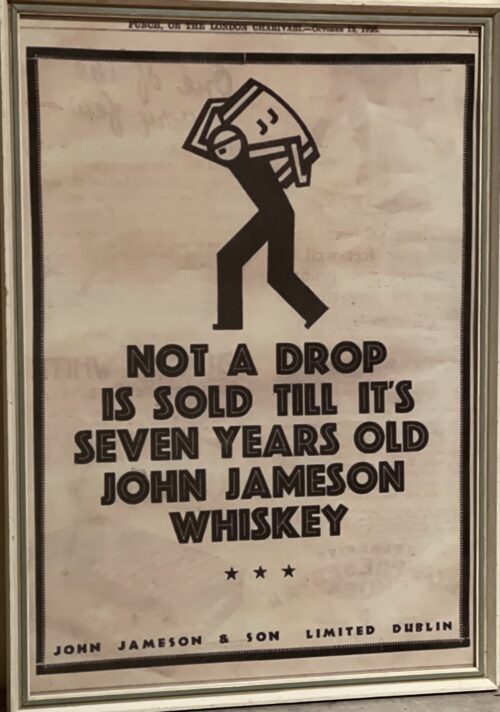

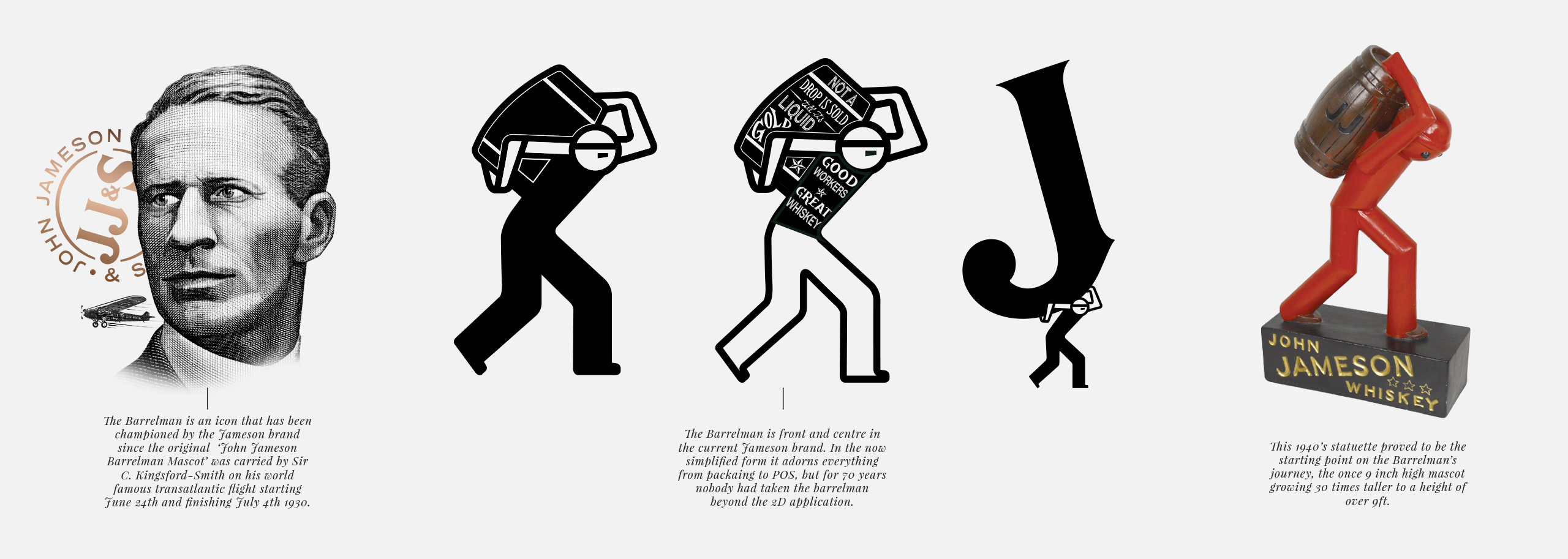

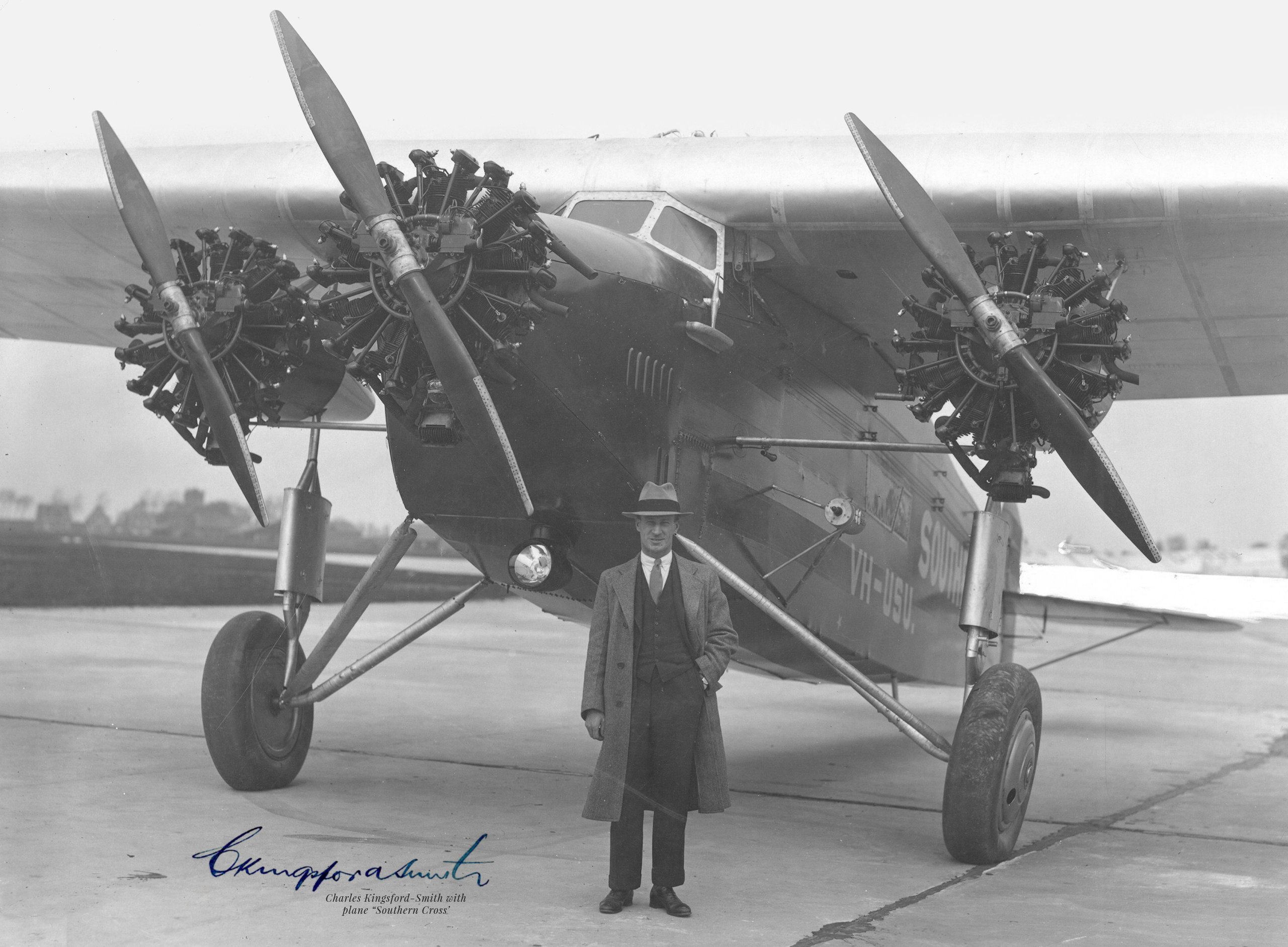

42cm x 31cm Vintage John Jameson Punch Magazine Advert from 1928 featuring the iconic Barrelman .WHY A BARRELMAN? In 1930 John Jameson made a barrelman mascot for aviator Sir C. Kingford-Smith. On June 24th 1930, the mascot took pride of place in the 'Southern Cross' plane that flew from Portmarnock, Ireland on the transatlantic odyssey to America. Since the making of this first lucky mascot, Jameson has revived the icon of the Barrelman, placing him front and centre on their communications.

42cm x 31cm Vintage John Jameson Punch Magazine Advert from 1928 featuring the iconic Barrelman .WHY A BARRELMAN? In 1930 John Jameson made a barrelman mascot for aviator Sir C. Kingford-Smith. On June 24th 1930, the mascot took pride of place in the 'Southern Cross' plane that flew from Portmarnock, Ireland on the transatlantic odyssey to America. Since the making of this first lucky mascot, Jameson has revived the icon of the Barrelman, placing him front and centre on their communications.

-

48cm x 35cm

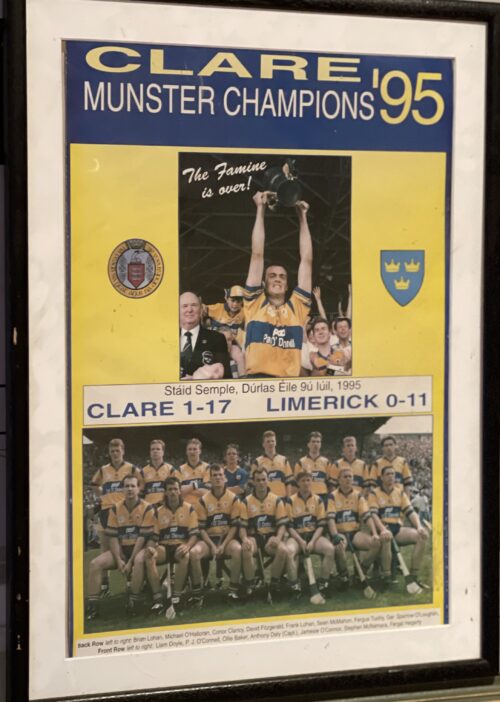

48cm x 35cmIt was Richie Connor in the early 1990s who first introduced me to the concept. For the Offaly team he captained, ultimately to the 1982 All-Ireland, beating Dublin in the 1980 Leinster final had he said been their most significant achievement.

This was because winning the province represented a longer journey from where the team under Eugene McGee had started than the distance from there to the Sam Maguire.

Maybe the reasoning was slightly different in Clare but it amounted to the same thing. In the few weeks that shimmered in the radiant summer of 1995 between winning Munster and the All-Ireland semi-final against Galway, manager Ger Loughnane was certainly of that view.

“In Clare, Munster is the Mount Everest. All along Munster was what was talked about. I remember stopping Nenagh on the way back from the League final and a man saying, ‘if only we could win Munster once, it would make up for everything’.

“The reaction to our winning Munster has been far greater than what would happen in other counties if they won an All-Ireland.”

Clare had got to the stage where they were being upstaged by their footballers whose first Munster title since 1917 had been sensationally won in 1992 leaving the hurlers by-passed.

Anthony Daly, prominent in 1995 as the exuberant captain of the hurlers, remembered the big-ball community’s notions. He went to support the footballers in their All-Ireland semi-final against Dublin three years previously. In a bar beforehand he was mocked for band-wagoning.

“Do you go to our matches at all,” asks Daly.

“I do, I do,” comes the response.

“And when you do, does anyone ever tell you to f*** off back to west Clare?”

Boom, boom.

Climbed Everest

Twenty-five years ago today (Thursday) the county hurlers climbed Everest and in unexpected style. Clare had qualified for a third successive Munster final but the previous two, against Limerick and Tipperary had ended in heavy defeats.