-

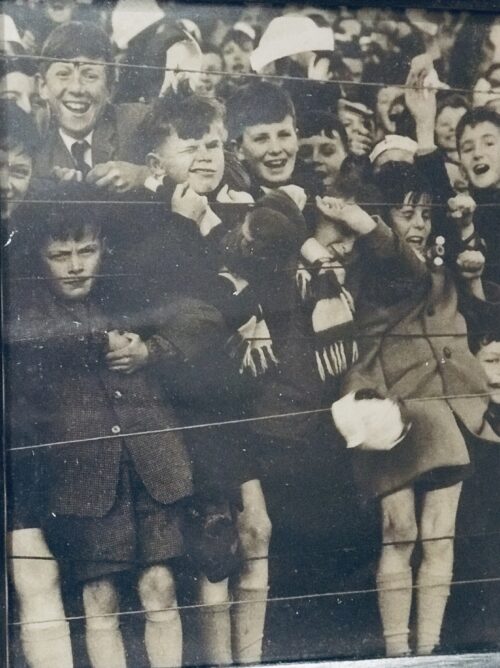

Team photo from before the 1977 All Ireland SemiFinal of that great Dublin side. Dublin 22cm x 27cm here have been many memorable battles between Dublin and Kerry down through the years, but the meeting between the two sides on the 21st of August 1977 has been described many times as the greatest game of all time. The country was gripped by this fierce rivalry that built up through the 70’s. This was the third year in a row that the two sides went toe to toe with both teams up claiming a win each. The game started at a furious pace that didn’t wane for the entire match. Dublin missed a couple of early goal chances and it was Kerry’s Seán Walsh hit the first three pointer to leave a goal between the sides at the break. Dublin though dominated the midfield sector particularly with the second half introduction Bernard Brogan. With the Dubs in the ascendancy early in the second period they took full advantage and a John McCarthy goal leveled the game brought them right back into it. The action flowed from one end of the Croke Park pitch to the other with the sides exchanging a flurry of points. The intensity levels rose dramatically both on the pitch and in the stands as this thriller continued to enthrall and excite throughout. But two late goals clinched it for Kevin Heffernan’s men, Tony Hanahoe gathered a loose ball around the middle, passed it off to David Hickey who strode forward and hit a brilliant shot to the back of the net for Dublin’s second goal. Just before the final whistle the Sky Blues grabbed their third goal, a sweeping move involving David Hickey, Tony Hanahoe and Bobby Doyle seen the ball end up in the hands of Bernard Brogan who unleashed a rocket which almost took the net off the goal and Dublin claimed a well deserved victory.

Team photo from before the 1977 All Ireland SemiFinal of that great Dublin side. Dublin 22cm x 27cm here have been many memorable battles between Dublin and Kerry down through the years, but the meeting between the two sides on the 21st of August 1977 has been described many times as the greatest game of all time. The country was gripped by this fierce rivalry that built up through the 70’s. This was the third year in a row that the two sides went toe to toe with both teams up claiming a win each. The game started at a furious pace that didn’t wane for the entire match. Dublin missed a couple of early goal chances and it was Kerry’s Seán Walsh hit the first three pointer to leave a goal between the sides at the break. Dublin though dominated the midfield sector particularly with the second half introduction Bernard Brogan. With the Dubs in the ascendancy early in the second period they took full advantage and a John McCarthy goal leveled the game brought them right back into it. The action flowed from one end of the Croke Park pitch to the other with the sides exchanging a flurry of points. The intensity levels rose dramatically both on the pitch and in the stands as this thriller continued to enthrall and excite throughout. But two late goals clinched it for Kevin Heffernan’s men, Tony Hanahoe gathered a loose ball around the middle, passed it off to David Hickey who strode forward and hit a brilliant shot to the back of the net for Dublin’s second goal. Just before the final whistle the Sky Blues grabbed their third goal, a sweeping move involving David Hickey, Tony Hanahoe and Bobby Doyle seen the ball end up in the hands of Bernard Brogan who unleashed a rocket which almost took the net off the goal and Dublin claimed a well deserved victory. -

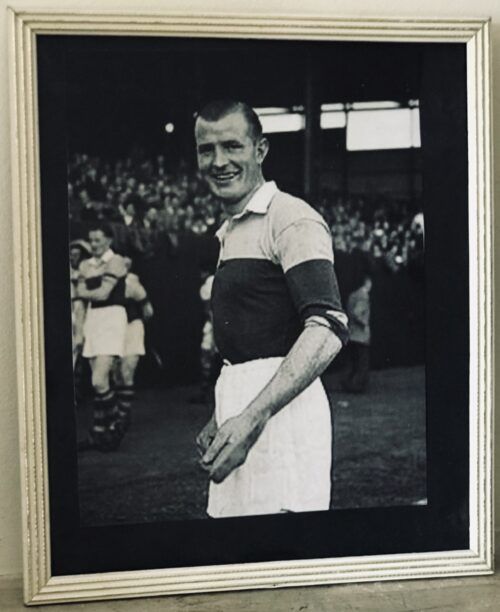

Poignant portrait of all time Wexford Hurling Great Nicky Rackard Enniscorthy Co Wexford 35cm x32cm "I was lucky enough to be on a Wexford team that he was involved with," recalled Liam Griffin. "He put his hand on my shoulder and that was like the hand of God touching you. "He was a fantastic man and his presence was just unbelievable. To see him standing there in a dressing-room, you wouldn't be worried about going out on the pitch, you'd just be looking at him." Despite his many years of service to Wexford GAA, Nicky Rackard's life was cut tragically short and at only the age of 53, the legendary hurler passed on after a battle with cancer. As Liam Griffin recalled on OTB AM, Rackard had also had his struggles with alcohol. "He was a gentleman as well, but look, he had his problems when he wasn't a gentleman as well when he had drink taken like most people," he explained. "But look, he was an inspiration too because he went on to do great work for alcoholics and so forth. "But I'm just going to say this, and I'm not saying this to be smart but because I mean it sincerely. After the All-Ireland final when we won it we put the cup in the middle of the floor the next morning after the All-Ireland. "In my view, he'd had such an influence on me and what we were that we stood around the cup and said a few prayers, and I'm not ashamed to say that I can tell you. "I warned them, and I meant it because I had thought about it in the previous weeks and months before, about any of them becoming an alcoholic, like Nicky Rackard. "He was one of the greatest but hero-worship is dangerous and when they walked out that door their lives would change forever. Nicky's life was spoiled by the worship he received and that's an unintended consequence, but it is the truth." The prominent figure upon Wexford's Mt Rushmore in Liam Griffin's opinion, whatever of Nicky Rackard's troubles in life, Griffin believes his legacy as a hurler is unsurpassed. "He led Wexford when we hadn't fields of barley let me tell you, we had pretty barren fields," he recalled. "Nicky Rackard carried on through a lot of thick and thin with Wexford, through a lot of heartache but he eventually put his flag on the top of the mountain. "He's #1 in Wexford, that's for sure."

Poignant portrait of all time Wexford Hurling Great Nicky Rackard Enniscorthy Co Wexford 35cm x32cm "I was lucky enough to be on a Wexford team that he was involved with," recalled Liam Griffin. "He put his hand on my shoulder and that was like the hand of God touching you. "He was a fantastic man and his presence was just unbelievable. To see him standing there in a dressing-room, you wouldn't be worried about going out on the pitch, you'd just be looking at him." Despite his many years of service to Wexford GAA, Nicky Rackard's life was cut tragically short and at only the age of 53, the legendary hurler passed on after a battle with cancer. As Liam Griffin recalled on OTB AM, Rackard had also had his struggles with alcohol. "He was a gentleman as well, but look, he had his problems when he wasn't a gentleman as well when he had drink taken like most people," he explained. "But look, he was an inspiration too because he went on to do great work for alcoholics and so forth. "But I'm just going to say this, and I'm not saying this to be smart but because I mean it sincerely. After the All-Ireland final when we won it we put the cup in the middle of the floor the next morning after the All-Ireland. "In my view, he'd had such an influence on me and what we were that we stood around the cup and said a few prayers, and I'm not ashamed to say that I can tell you. "I warned them, and I meant it because I had thought about it in the previous weeks and months before, about any of them becoming an alcoholic, like Nicky Rackard. "He was one of the greatest but hero-worship is dangerous and when they walked out that door their lives would change forever. Nicky's life was spoiled by the worship he received and that's an unintended consequence, but it is the truth." The prominent figure upon Wexford's Mt Rushmore in Liam Griffin's opinion, whatever of Nicky Rackard's troubles in life, Griffin believes his legacy as a hurler is unsurpassed. "He led Wexford when we hadn't fields of barley let me tell you, we had pretty barren fields," he recalled. "Nicky Rackard carried on through a lot of thick and thin with Wexford, through a lot of heartache but he eventually put his flag on the top of the mountain. "He's #1 in Wexford, that's for sure." -

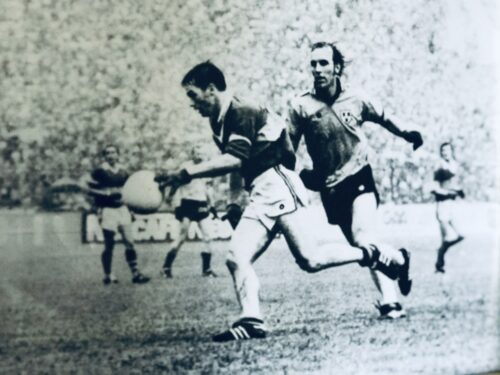

23cm x 29 cm. Baldoyle Dublin Atmospheric photo of Brian Mullins of Dublin following Paidi O Se of Kerry on a rain sodden Croke Park in 1978 Con’s description of Kerry player Mikey Sheehy’s free in the 1978 All Ireland Football Final between Dublin v Kerry is still the stuff of legend and is worth quoting again. Con wrote: “Dublin were like climbers who had been driven down the mountain by a rock fall – they had to set out again from the plateau not far from the base. And now came the moment that will go into that department of sport’s museum where abide such strange happenings as the Long Count and the goal that gave Cardiff their only English FA Cup and the fall of Devon Loch. Its run-up began with a free from John O’Keefe, deep in his own territory. Jack O’Shea made a flying catch and drove a long ball towards the middle of the 21 -yard line. Mikey Sheehy’s fist put it behind the backs, breaking along the ground out toward Kerry’s right. This time Paddy Cullen was better positioned and comfortably played the ball with his feet away from Sheehy. He had an abundance of time and space in which to lift and clear but his pick-up was a dubious one and the referee Seamus Aldridge, decided against him. Or maybe he deemed his meeting with Ger Power illegal. Whatever the reason, Paddy put on a show of righteous indignation that would get him a card from Equity, throwing his hands to heaven as the referee kept pointing towards goal. And while all that was going on, Mikey Sheehy was running up to take the kick-and suddenly Paddy dashed back towards his goal like a woman who smells a cake burning. The ball won the race and it curled inside the near post as Paddy crashed into the outside of the net and lay against it like a fireman who returned to find his own station ablaze. Sometime, Noel Pearson might make a musical of this amazing final and as the green flag goes up for that crazy goal he will have a banshee crooning: “And that was the end of poor Molly Malone.” And so it was. A few minutes later came the tea-break. Kerry went into a frenzy of green and gold and a tumult of acclaim. The champions looked like men who worked hard and seen their savings plundered by bandits.” .

23cm x 29 cm. Baldoyle Dublin Atmospheric photo of Brian Mullins of Dublin following Paidi O Se of Kerry on a rain sodden Croke Park in 1978 Con’s description of Kerry player Mikey Sheehy’s free in the 1978 All Ireland Football Final between Dublin v Kerry is still the stuff of legend and is worth quoting again. Con wrote: “Dublin were like climbers who had been driven down the mountain by a rock fall – they had to set out again from the plateau not far from the base. And now came the moment that will go into that department of sport’s museum where abide such strange happenings as the Long Count and the goal that gave Cardiff their only English FA Cup and the fall of Devon Loch. Its run-up began with a free from John O’Keefe, deep in his own territory. Jack O’Shea made a flying catch and drove a long ball towards the middle of the 21 -yard line. Mikey Sheehy’s fist put it behind the backs, breaking along the ground out toward Kerry’s right. This time Paddy Cullen was better positioned and comfortably played the ball with his feet away from Sheehy. He had an abundance of time and space in which to lift and clear but his pick-up was a dubious one and the referee Seamus Aldridge, decided against him. Or maybe he deemed his meeting with Ger Power illegal. Whatever the reason, Paddy put on a show of righteous indignation that would get him a card from Equity, throwing his hands to heaven as the referee kept pointing towards goal. And while all that was going on, Mikey Sheehy was running up to take the kick-and suddenly Paddy dashed back towards his goal like a woman who smells a cake burning. The ball won the race and it curled inside the near post as Paddy crashed into the outside of the net and lay against it like a fireman who returned to find his own station ablaze. Sometime, Noel Pearson might make a musical of this amazing final and as the green flag goes up for that crazy goal he will have a banshee crooning: “And that was the end of poor Molly Malone.” And so it was. A few minutes later came the tea-break. Kerry went into a frenzy of green and gold and a tumult of acclaim. The champions looked like men who worked hard and seen their savings plundered by bandits.” . -

26cm x 38cm Dublin O'Connell Street connects the O'Connell Bridge to the south of Dublin with Parnell Street to the north, and is roughly split into two sections bisected by Henry Street. The Luas tram system runs along the street. During the 17th century, it was a narrow street known as Drogheda Street, named after Henry Moore, Earl of Drogheda. It was widened in the late 18th century by the Wide Streets Commission and renamed Sackville Street after Lionel Sackville, 1st Duke of Dorset. In 1924, it was renamed in honour of Daniel O'Connell, a nationalist leader of the early 19th century, whose statue stands at the lower end of the street, facing O'Connell Bridge. The street has played an important part in Irish history and features several important monuments, including statues of O'Connell and union leader James Larkin, and the Dublin Spire. It formed the backdrop to one of the 1913 Dublin Lockout gatherings, the 1916 Easter Rising, the Irish Civil War of 1922, the destruction of the Nelson Pillar in 1966 and the Dublin Riots in 2006. In the late 20th century, a comprehensive plan was began to restore the street back to its original 19th century character. O'Connell Street evolved from the earlier 17th-century Drogheda Street, laid out by Henry Moore, 1st Earl of Drogheda. It was a third of the width of the present-day O'Connell Street, located on the site of the modern eastern carriageway and extending from Parnell Street to the junction with Abbey Street. In the 1740s, the banker and property developer Luke Gardiner acquired the upper part of Drogheda Street extending down to Henry Street as part of a land deal.He demolished the western side of Drogheda Street creating an exclusive elongated residential square 1,050 feet (320 m) long and 150 feet (46 m) wide, thus establishing the scale of the modern-day thoroughfare. A number of properties were built along the new western side of the street, while the eastern side had many mansions, the grandest of which was Drogheda House rented by the sixth Earl of Drogheda. Gardiner also laid out a mall down the central section of the street, lined with low granite walls and obelisks.It was planted with trees a few years later. He titled the new development Sackville Street after the then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland Lionel Cranfield Sackville, Duke of Dorset.It was also known as 'Sackville Mall', and 'Gardiner's Mall'. However, due to the limited lands owned by the Gardiners in this area, the Rotunda Hospital sited just off the street at the bottom of Parnell Square – also developed by the family – was not built on axis with Sackville Street, terminating the vista. It had been Gardiner's intention to connect the new street through to the river, however, he died in 1755, with his son Charlestaking over the estate. Work did not start until 1757, when the city's planning body, the Wide Streets Commission, obtained a financial grant from Parliament.For the next 10 years work progressed in demolishing a myriad of dwellings and other buildings, laying out the new roadway and building new terraces.The Wide Streets Commission had envisaged and realised marching terraces of unified and proportioned façades extending from the river.Because of a dispute over land, a plot on the northwest of the street remained vacant; this later became the General Post Office (GPO) which opened in 1814.The street became a commercial success upon the opening of Carlisle Bridge, designed by James Gandon, in 1792 for pedestrians and 1795 for all traffic.

26cm x 38cm Dublin O'Connell Street connects the O'Connell Bridge to the south of Dublin with Parnell Street to the north, and is roughly split into two sections bisected by Henry Street. The Luas tram system runs along the street. During the 17th century, it was a narrow street known as Drogheda Street, named after Henry Moore, Earl of Drogheda. It was widened in the late 18th century by the Wide Streets Commission and renamed Sackville Street after Lionel Sackville, 1st Duke of Dorset. In 1924, it was renamed in honour of Daniel O'Connell, a nationalist leader of the early 19th century, whose statue stands at the lower end of the street, facing O'Connell Bridge. The street has played an important part in Irish history and features several important monuments, including statues of O'Connell and union leader James Larkin, and the Dublin Spire. It formed the backdrop to one of the 1913 Dublin Lockout gatherings, the 1916 Easter Rising, the Irish Civil War of 1922, the destruction of the Nelson Pillar in 1966 and the Dublin Riots in 2006. In the late 20th century, a comprehensive plan was began to restore the street back to its original 19th century character. O'Connell Street evolved from the earlier 17th-century Drogheda Street, laid out by Henry Moore, 1st Earl of Drogheda. It was a third of the width of the present-day O'Connell Street, located on the site of the modern eastern carriageway and extending from Parnell Street to the junction with Abbey Street. In the 1740s, the banker and property developer Luke Gardiner acquired the upper part of Drogheda Street extending down to Henry Street as part of a land deal.He demolished the western side of Drogheda Street creating an exclusive elongated residential square 1,050 feet (320 m) long and 150 feet (46 m) wide, thus establishing the scale of the modern-day thoroughfare. A number of properties were built along the new western side of the street, while the eastern side had many mansions, the grandest of which was Drogheda House rented by the sixth Earl of Drogheda. Gardiner also laid out a mall down the central section of the street, lined with low granite walls and obelisks.It was planted with trees a few years later. He titled the new development Sackville Street after the then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland Lionel Cranfield Sackville, Duke of Dorset.It was also known as 'Sackville Mall', and 'Gardiner's Mall'. However, due to the limited lands owned by the Gardiners in this area, the Rotunda Hospital sited just off the street at the bottom of Parnell Square – also developed by the family – was not built on axis with Sackville Street, terminating the vista. It had been Gardiner's intention to connect the new street through to the river, however, he died in 1755, with his son Charlestaking over the estate. Work did not start until 1757, when the city's planning body, the Wide Streets Commission, obtained a financial grant from Parliament.For the next 10 years work progressed in demolishing a myriad of dwellings and other buildings, laying out the new roadway and building new terraces.The Wide Streets Commission had envisaged and realised marching terraces of unified and proportioned façades extending from the river.Because of a dispute over land, a plot on the northwest of the street remained vacant; this later became the General Post Office (GPO) which opened in 1814.The street became a commercial success upon the opening of Carlisle Bridge, designed by James Gandon, in 1792 for pedestrians and 1795 for all traffic.19th century

Sackville Street prospered in the 19th century, though there were some difference between the Upper and Lower streets. Lower Sackville Street became successful as a commercial location; its terraces ambitiously lined with purpose-designed retail units. As a result, a difference between the two ends of the street developed: the planned lower end successful and bustling next to the river, and the upper end featuring a mixture of less prominent businesses and old townhouses. Upon his visit to Dublin in 1845, William Makepeace Thackeray observed the street was "broad and handsome" but noted the upper section featured less distinctive architecture and had a distinct lack of patronage. During the 19th century, Sackville street changed in character from the Wide Streets Commission design into a boulevard of individual buildings. One of the world's first purpose-built department stores was such a building: Delany's New Mart 'Monster Store' which opened in 1853 was later purchased by the Clery family.It also housed the Imperial Hotel. Across the road, another elaborate hotel was built next to the GPO: the Hotel Metropole, in a high-French style. Similarly, the Gresham Hotel opened on Nos. 21–22 in 1817 to the north of the street in adjoining Georgian townhouses and was later remodelled, as it became more successful. As the fortunes of Upper Sackville Street began to improve in the second half of the century, other businesses began to open such as Turkish baths, later to be incorporated into the Hammam Hotel. Standard Life Assurancebuilt their flagship Dublin branch on the street, while the Findlater family opened a branch of their successful chain close to Parnell Street, as did Gilbey's Wine Merchants. The thoroughfare also became the centre of the Dublin tramways system, with many of the city's trams converging at the Nelson Pillar.By 1900, Sackville Street had become an important location for shopping and business, which led to it being called "Ireland's Main Street". During the 19th century, the street began to be known as "O'Connell Street" though this was to be considered its "nationalist" name.Thus, the Dublin Corporation was anxious as early as the 1880s to change the name, but faced considerable objections from local residents, who in 1884 secured a Court order that the Corporation lacked the powers to make the change. The necessary powers were granted in 1890, but presumably, it was felt best to allow the new name to become popular. Over the years the name O'Connell Street gradually gained popular acceptance, and the name was changed officially, without any protest, in 1924.Easter Rising and Independence

On 31 August 1913, O'Connell Street saw the worst incident in the Dublin lock-out, a major dispute between workers and the police. During a speech given by workers' rights activist James Larkin, police charged through the attending crowd and arrested him. The crowd began to riot, resulting in two deaths, 200 arrests and numerous injuries. During the Easter Rising of 1916, Irish republicans seized the General Post Office and proclaimed the Irish Republic, leading to the street's bombardment for a number of days by the gunboat Helga of the Royal Navy and several other artillery pieces which were brought up to fire on the north of the street. The thoroughfare also saw sustained small arms and sniper fire from surrounding areas. By Saturday, the rebels had been forced to abandon the GPO, which was burning, and held out in Moore Street until they surrendered. Much of the street was reduced to rubble, the damaged areas including the whole eastern side of the street as far north as Cathedral Street, and the terrace in between the GPO and Abbey Street on the western side.In addition, during the chaos that accompanied the rebellion, the inhabitants of the nearby slums looted many of the shops on O'Connell Street.The events had a disastrous impact on the commercial life of the inner city, causing around £2.5 million worth of damage. Some businesses were closed up to 1923, or never reopened. In the immediate aftermath of the Rising, the Dublin Reconstruction (Emergency Provisions) Act, 1916 was drafted with the aim of controlling the nature of reconstruction on the local area. The aim was to rebuild in a coherent and dignified fashion, using the opportunity to modernise the nature of commercial activity.Under the act, the city was to approve all construction and reject anything that would not fit with the street's character. The reconstruction was supervised and by City Architect Horace T. O'Rourke. With the exception of its Sackville Street façade and portico, the General Post Office was destroyed.A new GPO was subsequently built behind the 1818 façade. Work began in 1924, with the Henry Street side the first to be erected with new retail units at street level, a public shopping arcade linking through to Princes Street, and new offices on the upper floors. The Public Office underneath the portico on O'Connell Street reopened in 1929.O'Connell Street saw another pitched battle in July 1922, on the outbreak of the Irish Civil War, when anti-treaty fighters under Oscar Traynoroccupied the street after pro-treaty Irish National Army troops attacked the republican garrison in the nearby Four Courts.Fighting lasted from 28 June until 5 July, when the National Army troops brought artillery up to point-blank range, under the cover of armoured cars, to bombard the Republican-held buildings. Among the casualties was Cathal Brugha, shot at close range. The effects of the week's fighting were largely confined to the northern end of the street, with the vast majority of the terrace north of Cathedral Street to Parnell Square being destroyed, as well as a few buildings on the north-western side. In total, around three-quarters of the properties on the street were destroyed or demolished between 1916 and 1922. As a result, only one Georgian townhouse remains on the street into the 21st century. Because of the extensive destruction and rebuilding, most of the buildings on O'Connell Street date from the early 20th century. The only remaining original building still standing is No. 42 which now houses part of the Royal Dublin Hotel.Apart from the GPO building, other significant properties rebuilt after the hostilities include the department store Clerys which reopened in August 1922 and the Gresham Hotel which reopened in 1927. Despite improvements to the street's architectural coherence between 1916 and 1922, the street has since suffered from a lack of planning. Like much of Dublin of that time, property speculators and developers were allowed to construct what were widely accepted to be inappropriately designed buildings, often entailing the demolition of historic properties in spite of its Conservation Area status. Several Victorian and 1920s buildings were demolished in the 1970s including Gilbey's at the northern end in 1972, the Metropole and Capitol cinemas next to the GPO,and the last intact Wide Streets Commission buildings on the street dating from the 1780s.They were replaced with a number of fast food restaurants, shops and offices, that continue to be the main features along O'Connell Street in the 21st century. The street was given attention with Dublin City Council's O'Connell Street Integrated Area Plan (IAP) which was unveiled in 1998 with the aim of restoring the street to its former status. The plan was designed to go beyond simple cosmetic changes, and introduce control of the wider area beyond the street's buildings, including pedestrian and vehicle interaction, governance and preservation of architecture. Work on the plan was delayed, and reached approval in June 2003. The main features of the plan included the widening of footpaths and a reduction in road space, removing and replacing all trees, a new plaza in front of the GPO,and new street furnishings including custom-designed lampposts, litter bins and retail kiosks. The plan included the Spire of Dublin project, Dublin's tallest sculpture; constructed between December 2002 and January 2003, occupying the site of Nelson's Pillar.Numerous monuments were restored, including those of late 19th century Irish political leader Charles Stewart Parnell, radical early 20th-century labour leader Jim Larkin, prominent businessman and nationalist MP Sir John Grey, and the most challenging of all: the conservation of the O'Connell Monument standing guard at the southern entrance to the thoroughfare. This project was worked on for a number of months by an expert team of bronze and stone conservators before being unveiled in May 2005. All public domain works were completed in June 2006, finalising the principal objective of the IAP at a cost of €40 million.Work was disrupted by a riot centred on the street which erupted on 25 February 2006. A protest against a planned Loyalist march degenerated into vandalism and looting, with building materials from the works in progress being used as weapons and for smashing windows and fixtures. O'Connell Street has been designated an Architectural Conservation Area and an Area of Special Planning Control. This means that no buildings can be altered without Dublin City Council's permission, and fast food outlets, takeaways, cafes and amusement arcades are strictly controlled. In June 2015, Clerys suddenly closed after it was bought out by investment group Natrium Ltd, with the loss of over 400 jobs. In 2019, plans were announced to turn the premises into a four-star hotel. The street is used as the main route of the annual St. Patrick's Day Parade, and as the setting for the 1916 Commemoration every Easter Sunday. It also serves as a major bus route artery through the city centre. The modern tram, the Luas, has undergone an extension and trams now run once again through O'Connell Street. It only travels in one direction, the return loop, to link the system at St. Stephen's Green, runs via Marlborough Street, parallel with and east of O'Connell Street. Clerys department store, rebuilt in 1922Current and former monuments on O'Connell Street from south to north include: Daniel O'Connell: designed and sculpted by John Henry Foley and completed by his assistant Thomas Brock. Construction began in 1886 and the monument unveiled in 1883. William Smith O'Brien: by Thomas Farrell. Originally erected in 1870 on an island at the O'Connell Bridge entrance to D'Olier Street, it was moved to O'Connell Street in 1929. Sir John Gray: by Thomas Farrell. Both plinth and statue carved entirely of white Sicilian marble, it was unveiled in 1879.Gray was the proprietor of the Freeman's Journal newspaper and as a member of Dublin Corporation was responsible for the construction of the Dublin water supply system based on the Vartry Reservoir. James Larkin: by Oisín Kelly. A bronze statue atop a Wicklow granite plinth, the monument was unveiled in 1980. Anna Livia: by Eamonn O'Doherty. Constructed in granite and unveiled on 17 June 1988, it became quickly known for its nickname "The Floosy in the Jacuzzi". It was removed in 2001 as part of the reconstruction plans for O'Connell Street and moved to the Croppies' Acre Memorial Park in 2011.[16][63][64] Nelson's Pillar, a 36.8 m (121 ft) granite Doric column erected in 1808 in honour of Admiral Lord Nelson, formerly stood at the centre of the street on the site of the present-day Spire of Dublin. Blown up by republican activists in 1966, the site remained vacant until the erection of the Spire in 2003. Father Theobald Mathew: by Mary Redmond. The foundation stone was laid in 1890, and the monument unveiled in 1893. In 2016, the statue was removed to cater for the Luas tram extension to the north of the city. Charles Stewart Parnell: Parnell Monument by Irish-American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The 37 ft high obelisk sits on a Galway granite pylon, was organised by John Redmond and paid for through public subscription and unveiled in 1911 at the junction with Parnell Street, just south of Parnell Square.Sir John Gray, designed by Thomas Farrell and erected in 1879.

Clerys department store, rebuilt in 1922Current and former monuments on O'Connell Street from south to north include: Daniel O'Connell: designed and sculpted by John Henry Foley and completed by his assistant Thomas Brock. Construction began in 1886 and the monument unveiled in 1883. William Smith O'Brien: by Thomas Farrell. Originally erected in 1870 on an island at the O'Connell Bridge entrance to D'Olier Street, it was moved to O'Connell Street in 1929. Sir John Gray: by Thomas Farrell. Both plinth and statue carved entirely of white Sicilian marble, it was unveiled in 1879.Gray was the proprietor of the Freeman's Journal newspaper and as a member of Dublin Corporation was responsible for the construction of the Dublin water supply system based on the Vartry Reservoir. James Larkin: by Oisín Kelly. A bronze statue atop a Wicklow granite plinth, the monument was unveiled in 1980. Anna Livia: by Eamonn O'Doherty. Constructed in granite and unveiled on 17 June 1988, it became quickly known for its nickname "The Floosy in the Jacuzzi". It was removed in 2001 as part of the reconstruction plans for O'Connell Street and moved to the Croppies' Acre Memorial Park in 2011.[16][63][64] Nelson's Pillar, a 36.8 m (121 ft) granite Doric column erected in 1808 in honour of Admiral Lord Nelson, formerly stood at the centre of the street on the site of the present-day Spire of Dublin. Blown up by republican activists in 1966, the site remained vacant until the erection of the Spire in 2003. Father Theobald Mathew: by Mary Redmond. The foundation stone was laid in 1890, and the monument unveiled in 1893. In 2016, the statue was removed to cater for the Luas tram extension to the north of the city. Charles Stewart Parnell: Parnell Monument by Irish-American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The 37 ft high obelisk sits on a Galway granite pylon, was organised by John Redmond and paid for through public subscription and unveiled in 1911 at the junction with Parnell Street, just south of Parnell Square.Sir John Gray, designed by Thomas Farrell and erected in 1879. -

26cm x 33cm Fantastic shot of the most westerly GAA pitch in Ireland and prob in Western Europe-the pitch on Care Island where the resourceful locals have mangaged to produce a decent playing surface on the only flat patch of land on the island ! Inishturk (Inis Toirc in Irish, meaning Wild Boar Island) is an inhabited island of County Mayo, in Ireland.

26cm x 33cm Fantastic shot of the most westerly GAA pitch in Ireland and prob in Western Europe-the pitch on Care Island where the resourceful locals have mangaged to produce a decent playing surface on the only flat patch of land on the island ! Inishturk (Inis Toirc in Irish, meaning Wild Boar Island) is an inhabited island of County Mayo, in Ireland.Geography

The island lies about 15 km (9 mi) off the coast; its highest point reaches 189.3 m (621.1 ft) above sea level. Between Inisturk and Clare Island lies Caher Island. It has a permanent population of 58 people.There are two main settlements, both on the more sheltered eastern end of the island, Ballyheer and Garranty. Bellavaun and Craggy are abandoned settlements. The British built a Martello tower on the western coast during the Napoleonic Wars. Inisturk has the highest per capita donation rate towards the RNLI in the whole of Ireland.History

Inishturk has been inhabited on and off since 4,000 BCE and has been inhabited permanently since at least 1700. Some of the more recent inhabitants are descended from evacuees from Inishark to the southwest. The social club Mountain Common is situated on the hill that separates the two settlements.Recent history

In 1993 Inishturk Community centre was opened, this community centre doubles as a library and a pub. In June 2014 the ESB commissioned three new Broadcrown BCP 110-50 100kVA diesel generators to supply electricity to the island The ESB have operated a diesel power station on the island since the 1980s Inishturk gained international attention in 2016 after a number of websites claimed that the island would welcome any American "refugees" fleeing a potential Donald Trump presidency.These claims were used as one example of the type of "fake news" that arose during the 2016 US presidential election campaign. As of November 2016, no changes to inward migration have been reported. The island is home to a primary school on the island which in 2011 had only 3 pupils, this believed to be the smallest primary school in IrelandDemographics

The table below reports data on Inisturk's population taken from Discover the Islands of Ireland (Alex Ritsema, Collins Press, 1999) and the Censusof Ireland.Historical population Year Pop. ±% 1841 577 — 1851 174 −69.8% 1861 110 −36.8% 1871 112 +1.8% 1881 116 +3.6% 1891 135 +16.4% 1901 135 +0.0% 1911 132 −2.2% 1926 101 −23.5% Year Pop. ±% 1936 107 +5.9% 1946 125 +16.8% 1951 123 −1.6% 1956 110 −10.6% 1961 108 −1.8% 1966 92 −14.8% 1971 83 −9.8% 1979 85 +2.4% 1981 76 −10.6% Year Pop. ±% 1986 90 +18.4% 1991 78 −13.3% 1996 83 +6.4% 2002 72 −13.3% 2006 58 −19.4% 2011 53 −8.6% 2016 51 −3.8% Source: Central Statistics Office. "CNA17: Population by Off Shore Island, Sex and Year". CSO.ie. Retrieved October 12, 2016. Transport[edit]

Prior to 1997 there was no scheduled ferry service and people traveled to and from the islands using local fishing boats. Since then a ferry service operates from Roonagh Quay, Louisburgh, County Mayo.[13] The pier was constructed during the 1980s by the Irish government, around this time the roads on the island were paved.[14] -

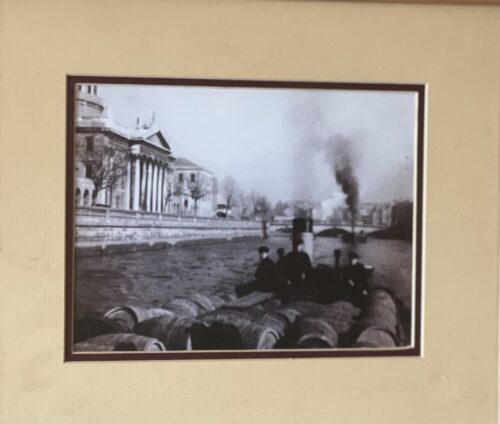

Beautifully mounted & framed 30cm x 30cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm

Beautifully mounted & framed 30cm x 30cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm -

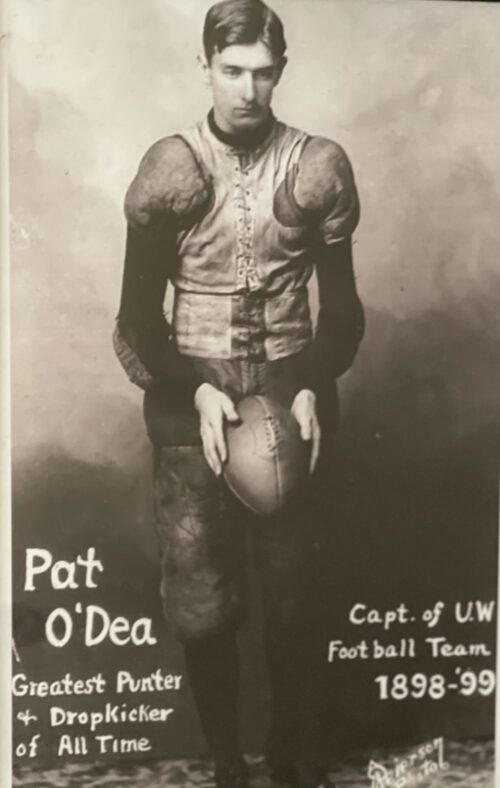

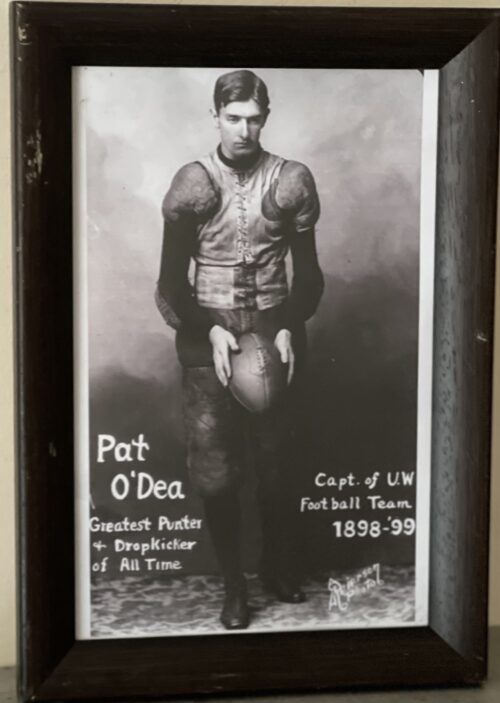

25cm x 35cm. Limerick Patrick John "Kangaroo Kicker" O'Dea (17 March 1872 – 5 April 1962) was an Irish-Australian rules and American footballplayer and coach. An Australian by birth, O'Dea played Australian rules football for the Melbourne Football Club in the Victorian Football Association (VFA). In 1898 and 1899, O'Dea played American football at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the United States, where he excelled in the kicking game. He then served as the head football coach at the University of Notre Dame from 1900 to 1901 and at the University of Missouri in 1902, compiling a career college footballrecord of 19–7–2. O'Dea was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame as a player in 1962.

25cm x 35cm. Limerick Patrick John "Kangaroo Kicker" O'Dea (17 March 1872 – 5 April 1962) was an Irish-Australian rules and American footballplayer and coach. An Australian by birth, O'Dea played Australian rules football for the Melbourne Football Club in the Victorian Football Association (VFA). In 1898 and 1899, O'Dea played American football at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the United States, where he excelled in the kicking game. He then served as the head football coach at the University of Notre Dame from 1900 to 1901 and at the University of Missouri in 1902, compiling a career college footballrecord of 19–7–2. O'Dea was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame as a player in 1962.Early life

O'Dea was born in Kilmore, Victoria, Australia to an Irish-born father and a Victorian-born mother. He was the third child of seven children. As a child he attended Christian Brothers College and Xavier College. As a 16-year-old he received a bronze medallion from the Royal Humane Society of Australasia for rescuing a woman at Mordialloc beach.Playing career

O'Dea played American football at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he was their star fullback from 1896–1899 and captained the 1898 and 1899 teams. In those days fullbacks punted and often did the placekicking. In the 1898 edition of the Northwestern game, which was played in a blizzard, he drop kicked a 62-yard field goal, and had a 116-yard punt. This earned him the nickname "Kangaroo Kicker". Wisconsin then headed into a Thanksgiving Day showdown with 1898 Western champions Michigan with only the narrow loss to Yale marring their record. New songs were composed for the occasion including “Oh, Pat O’Dea” to the popular tune “Margery”. The chorus ran: "Oh Pat O’Dea, oh Pat O’Dea, We love you more and more. Oh Pat O’Dea, oh Pat O’Dea, You’re the boy that we adore; Your leg is ever sure and true, And always kicks a goal or two. The team and rooters worship you. Oh Pat O’Dea." The final verse concluded: "To this brave lad forever we shall proudly sing. He is the boy we love. And in the games we play The cry “O’Dea, ”We’ll yell to every foe, because their game will show There is no other lad to see like Pat O’Dea. The East and West will surely have to see That we can’t lose in Patrick’s shoes, For he’s the only boy in all this land so free. The famous punter, Pat O’Dea." In the 1899 game, he returned a kickoff 90 yards for a touchdown, and had four field goals. He was selected as an All-American team member in 1899.Coaching career

Notre Dame

From 1900 to 1901, O'Dea coached at the University of Notre Dame, and compiled a 14–4–2 record.Missouri

O'Dea was the tenth head football coach for the University of Missouri–Columbia Tigers located in Columbia, Missouri and he held that position for the 1902 season. His career coaching record at Missouri was 5 wins, 3 losses, and 0 ties. This ranks him 22nd at Missouri in total wins and tenth at Missouri in winning percentage.Later life

After coaching, he disappeared from public view in 1917, having decided that he didn't like being treated as a celebrity, and it was assumed by Wisconsin fans that O'Dea had died fighting in World War I. In 1934, he was discovered living under an assumed name in California and came back to Wisconsin to a hero's welcome. He later appeared on Bob Hope's All-American football team announcement shows. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame on 3 April 1962. He died the next day at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center. Pat O'Dea died on 4 April 1962 at the age of 90 after an illness. While he was in hospital he received a get-well message from President John Kennedy. O'Dea's obituary in the New York Times commented on his kicking achievements including a 110-yard punt, though against Minnesota in 1897 and not Yale in 1899, and his 62-yard goal against Northwestern in 1898. -

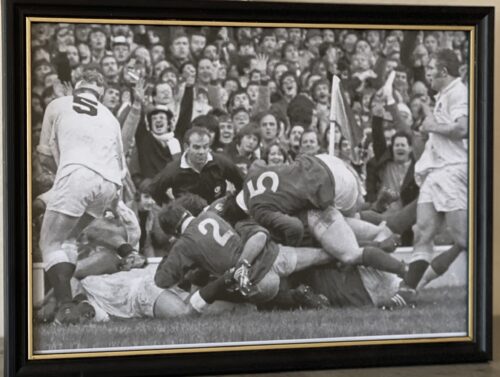

Gerry ‘Ginger' McLoughlin – better known as ‘Locky' in his native Limerick - was instrumental in winning the 1982 Triple Crown, Ireland's first since 1949. Below, ‘Locky' tells of his flirtation with the priesthood, Limerick's rugby rivalries and great players, his call-up to international rugby and the fateful tour to apartheid South Africa which impacted on his teaching career By Dave McMahon There are few contenders for the most memorable Irish try of the last 50 years. A generation who remember the days of black and white television will cite Pat Casey's ‘criss-cross' try against England at Twickenham in 1964 when Mike Gibson's searing break gave Jerry Walsh the opportunity to deliver the decisive reverse pass. Gordon Hamilton's superb burst to score in the Lansdowne Road corner against Australia in the 1991 World Cup ranks high in the list – a try that rarely gets the credit it deserves because of Michael Lynagh's instant riposte. Nearer the present day, the delayed October Six-Nations game against England in 2001 saw Keith Wood score one of the great forwards inspired try's against the auld enemy at Lansdowne Road. A try, indeed, which gave purists as much pleasure as any, with the pack orchestrating the score with military precision. The line-out throw from Wood; Galwey's clean take; Foley's magical hands; Eric Miller doing just enough to create the running channel; Wood's powerful burst through Neil Back's tackle for the touchdown. And then, you had Locky's try against England at Twickenham in the Triple Crown winning year of 1982 – a different class! In recalling 1982, it's Gerry McLoughlin's try that represents the defining moment of Ireland's first Triple Crown winning year since 1949. Ollie Campbell's touchline conversion of McLoughlin's try (pictured left) helped Ireland to a 16-15 victory and an ultimately successful Triple Crown decider against Scotland two weeks later. Three generations of Irish rugby heroes had come and gone without Triple Crown success – McBride, Kiernan, Dawson, O'Reilly, Gibson, and Goodall. Gerry McLoughlin's try helped create history, and he isn't slow to trumpet his role in '82.“At the time, I was misquoted as saying I dragged the Irish pack over the line with me.In fact, I dragged the entire Irish and English forwards across the line that day! Also, I never got the credit for creating the free which led to my try. As Steve Smith was about to put-in at an English scrum, I whispered to Ciaran Fitzgerald that I intended to pull the scrum, which I did successfully with the result that Smith was penalised for crooked-in. After the free was taken, I took over.” It was a tremendous year for McLoughlin during a rugby career which had its share of heartbreak as well as some glorious highs. “As a young man, I dabbled with hurling and gaelic football as a full-back or full-forward with St. Patrick's CBS. I had no great skill at either code; I simply mullocked and laid into guys. My destiny was certainly never to be a skillful All-Ireland winning hurler with Limerick. Rugby was always going to be my game. “Brian O'Brien got three Irish caps in 1968 and I regarded him as a hero, so it was always on that I should join Shannon, while my late father, Mick, had won Transfield Cup medals with the parish side. Joining Shannon at 16, my bulk and size immediately saw me go into the front-row where I had Michael Noel Ryan, who had captained the first-ever Shannon team to win the Munster Senior Cup, as a sound mentor. “Frankly, at the time, I didn't plan on a rugby career as I had other designs on my life. As soon as I entered Sexton Street CBS, my admiration for the role that the Christian Brothers played in Irish society saw me develop a vocation to become a Christian Brother. I spent a 3 year novitiate between Carriglea Park in Dun Laoghaire and St. Helens in Booterstown and was within 3 weeks of taking my vows of poverty, chastity and obedience before deciding that I wanted to opt out. “Had I taken the vows, I would have entered a world where there was no television, no newspapers and would not be able to take holidays or see my family for the best part of five years. That's the way it was in those days. I was at a young impressionable age and, in the end, I got stage fright and returned to Sexton Street as a pupil. “At 18, I was in the Shannon senior-cup team and I knew that I had some ability. After Sexton Street, I went to UCG to do my BA and that gave me the opportunity of further developing my rugby skills as I joined Ciaran Fitzgerald in the Colleges senior front-row. I won a handful of senior caps with Connacht who were not very successful at the time. The highlight of my Connacht career came when we ended a near 10-year losing run by beating, believe it or not, Spain by 7-3 in 1973. I played with some decent players in my days with Connacht, Mick Molloy and Leo Galvin were often in the second-row, while Mick Casserly was probably the best wing-forward never to be capped by Ireland.” After graduating from UCG, and the successful completion of a teacher-training degree with UCC, McLoughlin returned to his alma mater Sexton Street CBS as an Economics teacher in 1973 – and to the front-row in a Shannon senior-team that was about to make it's mark on the Irish rugby scene. “In those days, the rivalry between Limerick clubs was intense. Young Munster was a proud working-class club that commanded tremendous support and playing against them, especially in Greenfields, was often tougher than the Cardiff Arms Park. Reputations counted for nothing. You ignored hamstrings, cuts, strains and blood – you earned respect against them.” “Of course, Garryowen set the standard with their huge number of Munster Cup victories. In my time, they had a great full-back in Larry Moloney. Just four caps with Ireland was no reward for his ability. Despite spending 13 years of my life in Wales, the edge between Shannon and Garryowen is deeply engrained in my brain. Time hasn't diminished that rivalry. “People speak of Limerick rugby and the syndrome of doctor and docker playing side by side. That was certainly the case with Garryowen. Mick Lucey and Len Harty were doctors who played in the light blues three-quarter line in the late 60's. Then, you often had Dr. Jim Molloy playing in the Garryowen pack alongside Tom Carroll who was a Limerick docker. To this day, I maintain that Carroll was both the toughest and technically most proficient prop-forward I ever encountered. Tom was not much more than 13 stone, yet I never got the better of him. “In my early days with Shannon, we hardly rated on the rugby map. Teams like Trinity and Wanderers didn't want games against us. Garryowen were the standard bearers in Limerick and our aim was to become as good as them. After I returned from UCG in 1973, Shannon, with Brian O'Brien pulling the strings, had begun to assemble a powerful team. Brendan Foley was a fine second-row and an inspirational captain. Colm Tucker was the best ball-carrying wing-forward I ever played with. Colm was good enough to play in two tests for the Lions against South Africa in 1980, yet he was only capped on three occasions by Ireland. That was an absolute joke. “You would go a long way before finding better club forwards than my brother Mick, Eddie Price, Johnny Barry and Noel Ryan. Later, Niall O'Donovan came through as an outstanding number eight. Noel Ryan, indeed, was such a good loose-head prop that I played all my games for Shannon and, subsequently, Ireland at tight-head, while my entire career with Munster, and a handful of games with the Lions in 1983, was in the loose-head position. Playing on either side of the scrum never presented problems as the emphasis in training with Shannon was always on having a powerful scrummage as a starting-point.” Just six months after representing Connacht against Spain, McLoughlin won his first Munster ‘cap' in a fiery encounter against Argentina at Thomond Park. That was the start of a long interprovincial career which lasted from 1983 to 1987. An ever-present in the Munster team, the breakthrough to International level proved daunting and is the source of fiery comment from McLoughlin. “As I was a regular with Munster, I was asked to submit a CV by the IRFU to facilitate any calling to International level. I did all the right things. I deducted a year from my age with the result that my birth date changed from 11 June 1951 to 11 June 1952. I added a half-inch to my height to make sure that I came in as a sturdy six footer. I weighed 13 stone, 11 ounces those days and I remember sticking 7 pounds of lead into my jockstrap at a formal weigh-in to hit the 14 stone, 4 ounce mark. Still, the call to international representation was light years away. Ciaran Fitzgerald knew my correct age, but kept it quiet for years before revealing all to the IRFU one evening when he had a few too many. At that stage, it didn't matter. “The selection system was just a joke with two Leinster, two Ulster and a solitary Munster selector, with Connacht having no representation at all. To this day, I often wonder how Ciaran Fitzgerald was ever capped. I played some fine rugby for Munster over many years, yet I never came close to making the International scene and I doubt that I would have were it not for Munster beating the All Blacks in 1978. The selectors found it impossible to ignore us after that. I was also very lucky that Brian O'Brien eventually came through as an Irish selector. For years, he kept me in a ‘job', and I kept him in a ‘job'.” Munster's victory over New Zealand remains the most emotional game of McLoughlin's career. “It wasn't a fluke by any means as that was a superb Munster team. For starters, the usual Cork/Limerick selectorial carve-up didn't apply as twelve of the Munster team picked themselves. We had leaders and quality players all over the field. Wardie (Tony Ward) was under pressure all day, but still managed to kick brilliantly for position; Canniffe gave him a great service; Dennison and Barrett never stopped tackling; Larry Moloney was himself at full-back; Andy Haden might have won the line-out battle, but we matched the All Blacks forwards everywhere else; in the end, we fully deserved our 12-0 victory. “After that success over New Zealand, I was totally focused on making the step up to International level. I was often asked for tips by budding prop-forwards, but I never revealed anything useful in case the younger man got better than me. You spend all your career striving to get to the top and the last thing you wanted was someone to get ahead of you in the race. I had to be both dedicated and selfish.” Just three months after beating New Zealand and a successful final-trial outing with the probables, McLoughlin made his international debut against France. He may have been listed as ‘G.A.J. McLoughlin' on the match programme, but Limerick rugby followers still called him ‘Locky' – one of their own! Woe betide the fate of any Dublin hack that resorted to ‘Ginger'. Nearly 30 years after his International debut, he is still ‘Locky' in Limerick, but the metropolitan media continually refer to him as ‘Ginger'. But what's in a name? Some 10 years ago an almost fatal blow was struck against the ‘Locky' constituency. With the future of Connacht rugby under threat, a protest march to IRFU headquarters at Lansdowne Road was made. Remembering his youthful days in UCG and that famous victory over Spain, Gerry McLoughlin was at the forefront of the parade with a banner which read “Ginger supports Connacht rugby”. Locky or Ginger? Take your pick. If the Triple Crown and Munster's victory over the All Blacks were career highlights, McLoughlin's decision to tour South Africa with Ireland in 1981 cast a long shadow over his life. “I was teaching in Sexton Street at the time and initially got approval from the school to travel. However, just a week before we were due to depart, a change of management took place within the school and my permission to travel was withdrawn. It left me with a very difficult decision to make. I was married with a young family, but I dearly wanted to represent my country. Also, I felt that South Africa were making advances on apartheid. Errol Tobias, in fact, became the first non-white player to wear the Springboks jersey in a full-international against Ireland. In the end, I resigned my teaching position and travelled with Ireland.” In rugby terms, McLoughlin's decision to travel was justified as he regained his Irish place and played in both tests. However, it was altogether different on a personal level. “On my return from South Africa, I was advised that I had a solid legal case against my former employers in Sexton Street but I decided against taking any action as I had a great love of the Christian Brothers and had witnessed the benefits which their dedication gave to generations of children. They were put under severe pressure at the time as apartheid was a political and social time-bomb.” McLoughlin is far less forgiving when it came to the IRFU post-South Africa. “I wrote to every school in the country and couldn't get an interview, never mind get a job. The IRFU had plenty of people in positions of power, but the support from that quarter was nil. Ray McLoughlin (no relation) and Mick Molloy did offer considerable help at the time. Other than that, I was largely left to fend for myself.” From a remove of nearly 30 years, McLoughlin is philosophical. “It was my decision to travel to South Africa – I had to accept the consequences.” A part-time job teaching in the Municipal Institute of Technology followed, but that was never going to be enough to support a young family. The painful decision to emigrate to Wales was taken, after recession forced McLoughlin to close his pub – aptly named The Triple Crown – which he owned for five years. “In all, I spent 13 years in Wales, teaching in Gilfach Goch near Pontypridd during the day and running a pub in the evenings before deciding to return to Ireland. At the moment, my daughter Orla, who is getting married next August, is based in Limerick, while my three sons, Cian, Fionn and Emmet are in Wales where they spent so much of their youth.” Nowadays, living in Garryowen in the shade of St. John's Cathedral, Gerry McLoughlin enjoys a contented social and political life. “I was elected to the Limerick City Council as an Independent in 2004, before subsequently joining the Labour party. I had always admired the social vision of the late Jim Kemmy, so the move to Labour was a natural progression for me. “On a professional level, I'm energised by the day job as a social needs assistant at St. Mary's Boys School in the heart of the parish. I'm a lifetime non-smoker and I haven't touched alcohol in the last 14 years. I have a hectic political schedule, but I also find plenty of time to engage in worthwhile community work. “Recently, we formed an under 13/14 girls soccer club in Garryowen and I'm involved as Treasurer. Also, I coach St. Mary's under-age teens in rugby on Sunday mornings, while I have a similar role in soccer coaching with Star Rovers youngsters. Nowadays, my ambition is to give every child the opportunity to kick a ball.” The man who once propped against the famous Pontypool front-row confesses to a surprising social outlet: “I had a knee replacement operation in 2004 and that gave me the freedom to enjoy ballroom dancing on at least three evenings a week. It's wonderful for social relaxation”. Gerry McLoughlin has few, if any, regrets about his rugby career. “In the current era, I might have won 50 instead of 18 caps, but I have the memory of never losing in an Irish jersey at Lansdowne Road and I wouldn't change the Triple Crown success or beating the All Blacks for anything. Would I do things differently? Possibly. I might have deducted two years from my age if I was starting all over again!”