History

John Walker was born on 25 July 1805. His farmer father died in 1819, and the family sold the farm. Their trustees invested the proceeds, £417, in an Italian warehouse, grocery, and wine and spirits shop on the High Street in Kilmarnock,

Ayrshire, Scotland. Walker managed the grocery, wine, and spirits segment as a teenager in 1820. The Excise Act of 1823 relaxed strict laws on distillation of whisky and reduced, by a considerable amount, the extremely heavy taxes on the distillation and sale of whisky.

By 1825, Walker, a teetotaller, was selling spirits, including rum, brandy, gin, and whisky.

In short order, he switched to dealing mainly in whisky. Since blending of grain and malt whiskies was still banned, he sold both blended malt whiskies and grain whiskies.

They were sold as made-to-order whiskies, blended to meet specific customer requirements, because he did not have any brand of his own.

He began using his name on labels years later, selling a blended malt as

Walker's Kilmarnock Whisky. John Walker died in 1857.

The brand became popular, but after Walker's death it was his son

Alexander ‘Alec’ Walker and grandson

Alexander Walker II who were largely responsible for establishing the whisky as a favoured brand. The Spirits Act of 1860 legalised the blending of grain whiskies with malt whiskies and ushered in the modern era of blended Scotch whisky.

Blended Scotch whisky, lighter and sweeter in character, was more accessible, and much more marketable to a wider audience.

Andrew Usher of

Edinburgh, was the first to produce a blended whisky, but the Walkers followed in due course.

Alexander Walker had introduced the brand's signature square bottle in 1860. This meant more bottles fitting the same space and fewer broken bottles. The other identifying characteristic of the Johnnie Walker bottle was – and still is – the label, which, since that year, is applied at an angle of 24 degrees upwards left to right and allows text to be made larger and more visible.

This also allowed consumers to identify it at a distance.

One major factor in his favour was the arrival of a railway in Kilmarnock, carrying goods to merchant ships travelling the world. Thanks to Alec's business acumen, sales of Walker's Kilmarnock reached 100,000 gallons (450,000 litres) per year by 1862.

In 1865, Alec created Johnnie Walker's first commercial blend and called it

Old Highland Whisky, before registering it as such in 1867.

Under John Walker, whisky sales represented eight percent of the firm's income; by the time Alexander was ready to pass on the company to his own sons, that figure had increased to between 90 and 95 percent.

In 1893,

Cardhu distillery was purchased by the Walkers to reinforce the stocks of one of the Johnnie Walker blends' key malt whiskies.

This move took the Cardhu single malt out of the market and made it the exclusive preserve of the Walkers.

Cardhu's output was to become the heart of the

Old Highland Whisky and, subsequent to the rebranding of 1909, the prime single malt in Johnnie Walker Red and Black Labels.

From 1906 to 1909, John's grandsons George and Alexander II expanded the line and had three blended whiskies in the market,

Old Highland at 5 years old,

Special Old Highland at 9 years old, and

Extra Special Old Highland at 12 years old. These three brands had the standard Johnnie Walker labels, the only difference being their colours: white, red, and black respectively. They were commonly referred to in public by the colours of their labels.

In 1909, as part of a rebranding that saw the introduction of the Striding Man, a mascot used to the present day that was created by cartoonist

Tom Browne,

the company re-branded their blends to match the common colour names. The Old Highland was renamed

Johnnie Walker White Label,

and made a 6 year old, the Special Old Highland became

Johnnie Walker Red Label at 10 years old, and

Extra Special Old Highland was renamed

Johnnie Walker Black Label, remaining 12 years old.

Sensing an opportunity to expand the scale and variety of their brands, Walker acquired interests in Coleburn Distillery in 1915, quickly followed by

Clynelish Distillery Co. and Dailuaine-Talisker Co. in 1916.

This ensured a steady supply of single-malt whisky from the

Cardhu, Coleburn,

Clynelish,

Talisker, and

Dailuaine distilleries.

In 1923, Walker bought

Mortlach distillery, in furtherance of their strategy.

Most of their output was used in Johnnie Walker blends, whose burgeoning popularity required increasingly vast volumes of single malts.

Johnnie Walker White was dropped during

World War I.

In 1932, Alexander II added

Johnnie Walker Swing to the line, the name originating from the unusual shape of the bottle, which allowed it to rock back and forth.

The company joined

Distillers Company in 1925. Distillers Company was acquired by

Guinness in 1986, and Guinness merged with

Grand Metropolitan to form

Diageo in 1997. That year saw the introduction of the blended malt, Johnnie Walker Pure Malt, renamed as Johnnie Walker Green Label in 2004.

In 2009, the brand's owners, Diageo, decided to close all operations in Kilmarnock. This met with backlash from local people, local politicians, and then

First Minister of Scotland,

Alex Salmond. Despite petitions, public campaigns, and a large-scale march around Kilmarnock, Diageo proceeded with the closure.

The Johnnie Walker plant in Kilmarnock closed its doors in March 2012 and the buildings were subsequently demolished.

Blends

For most of its history Johnnie Walker only offered a few blends. Since the turn of the century, there has been a spate of special and limited bottlings.

- Red Label: A non-age-stated blend. It has been the best selling Scotch whisky in the world since 1945.It is primarily used for making mixed drinks.

- Black Label: Aged 12 years, it is one of the world's best-selling Scotch whiskies.

- Double Black Label: Made available for general release in 2011 after a successful launch in travel retail.The whisky was created taking Black Label as a blueprint, adding more peaty malt whiskies to it and maturing it in heavily charred old oak casks.

- Green Label: First introduced in 1997 as Johnnie Walker Pure Malt 15 Year Old,it was renamed Johnnie Walker Green Label in 2004. Green Label is a blended malt whisky, meaning it is made by mixing single malts with no grain whisky added.All whiskies used are a minimum of 15 years old.Diageo discontinued Green Label globally in 2012 (except for Taiwan, where demand for blended malts is very strong), as part of a reconstruction of the range that saw the introduction of Gold Label Reserve and Platinum Label. The brand was reintroduced in 2016 and is again globally available.

- Gold Label: A blend of over 15 single malts, it was derived from Alexander Walker II's blending notes for a whisky to commemorate Johnnie Walker's centenary. Originally, Gold Label was bottled at 18 years and labelled "The Centenary blend".In 2013, Gold Label was renamed "Gold Label Reserve", and now carries no age statement.

- Aged 18 Years: Originally introduced as Platinum Label, it was introduced to replace the original Gold Label in the Asian market, and sold alongside Gold Label Reserve. Though still available around the globe, the Platinum Label name was discontinued in mid-2017 and replaced by Johnnie Walker Aged 18 Years. The two are identical except for the label.

Johnnie Walker Blue label bottle in a gift box

- Blue Label: Johnnie Walker's premium blend. Johnnie Walker Blue Label is blended to recreate the character and taste of some of the earliest whisky blends created in the 19th century.[39] It bears no age statement. Bottles are numbered serially and sold in a silk-lined box accompanied by a certificate of authenticity. It is one of the most expensive blended Scotch whiskies on the market, with prices in the range of US$174–450.Over 25 Limited Editions have been released to date.

- Johnnie Walker Swing: Supplied in a distinctive bottle whose irregular bottom allows it to rock back and forth. This type of bottle design was originally used aboard sailing ships. It was Alexander Walker II's last blend: it features a high proportion of Speyside malts, complemented by malts from the northern Highlands and Islay.

The Walkers created their primary marketing strategy in 1908 with advertisements featuring Browne's Striding Man, using the slogan, "Johnnie Walker: Born 1820, still going strong". Photographs replaced the drawings in the 1930s, and the Striding Man was miniaturised to a coloured logo in 1939; it first appeared on the Johnnie Walker labels in 1960. In the late 1990s, the direction of the Striding Man was reversed as part of a "Keep Walking" campaign.

The Striding Man icon was most recently redrawn in 2015.

In 2009, the advertising agency

Bartle Bogle Hegarty (BBH) created a new short film, starring

Robert Carlyle and directed by Jamie Rafn, titled

The Man Who Walked Around the World, which outlined the history of the Johnnie Walker brand.

Johnnie Walker also launched the international John Walker & Sons Voyager tour in order to market its higher variants in the Asia-Pacific, Europe and Caribbean markets. The Voyager tour was developed in order to promote the special edition Odyssey blend and pay tribute to the original trade routes and sea voyages by which Johnnie Walker was distributed throughout the world.

In October 2018, Diageo teamed with

HBO to produce "White Walker by Johnnie Walker" whisky, inspired by the

army of the undead in the TV series

Game of Thrones as part of the marketing for the series' final season.

[45] Diageo then released a collection of

Game of Thrones–inspired single malt whiskies,

followed by two more whiskies by Johnnie Walker in mid-2019.

Accolades

Johnnie Walker spirits have received strong scores at international

spirit ratings competitions and from liquor review bodies. The Green Label received a string of three double gold medals from the San Francisco World Spirits Competition between 2005 and 2007.

The Gold Label received double gold medals from the San Francisco competition in 2008 and 2009 and won a gold in 2010.

Spirits ratings aggregator proof66.com, which averages scores from the San Francisco Spirits Competition, Wine Enthusiast, and others, puts the Black, Blue, Gold and Green Labels in its highest performance category ("Tier 1" Spirits).

Johnnie Walker spirits have several times taken part in the

Monde Selection's World Quality Selections and have received a Gold and Grand Gold Quality Award.

Johnnie Walker was voted India's Most Trusted Premium Whisky Brand according to the

Brand Trust Report 2014, a study conducted by Trust Research Advisory.

Johnnie Walker Gold Label Reserve won the World's Best Blended -- Best Scotch Blended in World Whiskies Awards 2018.

Johnnie Walker is the official whisky of

Formula One,

and are a sponsor of two

F1 teams

McLaren and

Racing Point. Johnnie Walker is also the title namesake for the F1 Grand Prix race in Spa Belgium.

Johnnie Walker sponsored the

Johnnie Walker Classic, an Asia-Pacific golf tournament, up to 2009 and the

Johnnie Walker Championship at Gleneagles, a golf tournament in Scotland up to 2013.

Diageo sold the Gleneagles Hotel and Golf Course, the site of the tournament, mid-2015 to focus on its core business.

Cultural figures

Winston Churchill's favourite whisky was Johnnie Walker Red Label, which he mixed with water and drank throughout the day.

Vanity Fair writer

Christopher Hitchens was partial to Johnnie Walker Black Label cut with Perrier and referred to it as "Mr Walker's Amber Restorative".

Johnnie Walker Blue Label was a favourite of the late US president

Richard Nixon's; Nixon used to enjoy it with

ginger ale and a wedge of lime.

A number of singers and songwriters have referenced Johnnie Walker in their works, from

Amanda Marshall to

ZZ Top.

Elliott Smith's

Oscar-nominated "

Miss Misery" has the narrator "[making] it through the day with some help from Johnnie Walker Red." Heavy metal band

Black Label Society was named after Johnnie Walker Black Label whisky, as

Zakk Wylde was very fond of the drink.

George Thorogood name checks “Johnny Walker and his brothers Black and Red” in "

I Drink Alone".

Polish fictional humorous character

Jakub Wędrowycz is a word play based on Polish translation of "Johny Walker".

Gallery

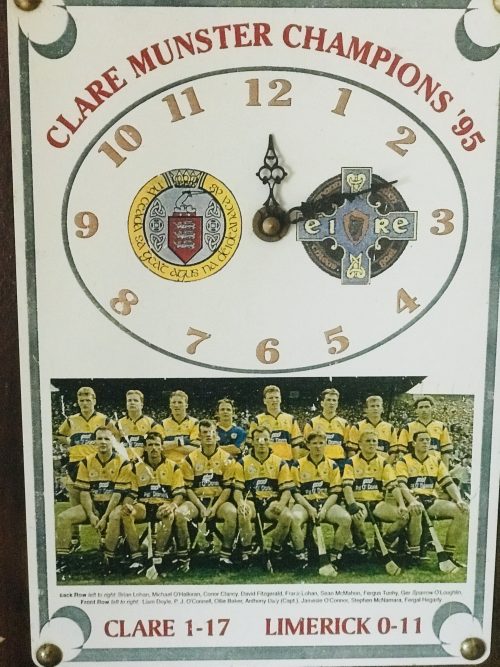

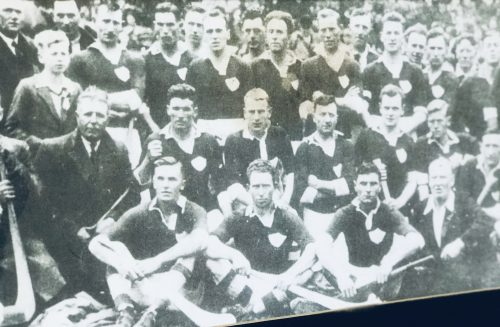

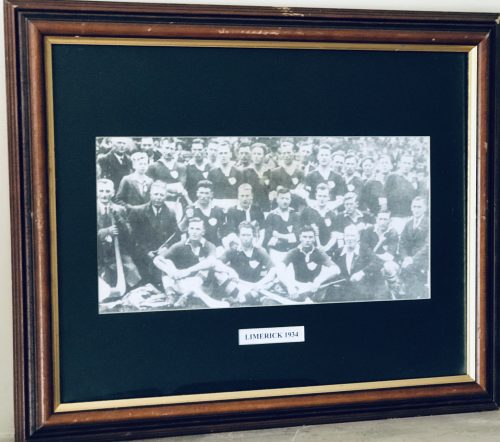

Limerick 5-2 Dublin 2-6

D Clohessy 4-0, M Mackey 1-1, J O’Connell 0-1

Limerick 5-2 Dublin 2-6

D Clohessy 4-0, M Mackey 1-1, J O’Connell 0-1

Tom Moloughney, Jimmy Doyle, and Kieran Carey relax in the dressing room after Tipperary’s victory over Dublin in the 1961 All-Ireland final, a success that was to be repeated the following year. Picture from ‘The GAA — A People’s History’

Tom Moloughney, Jimmy Doyle, and Kieran Carey relax in the dressing room after Tipperary’s victory over Dublin in the 1961 All-Ireland final, a success that was to be repeated the following year. Picture from ‘The GAA — A People’s History’