|

|

|

|

| Introduced | 1879, renamed as Paddy in 1912 |

|---|---|

-

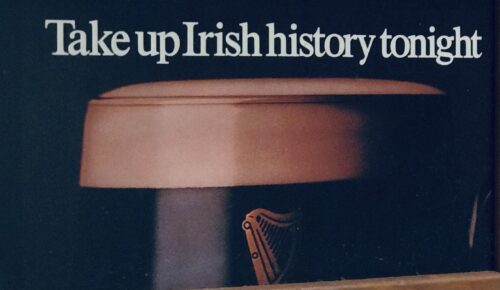

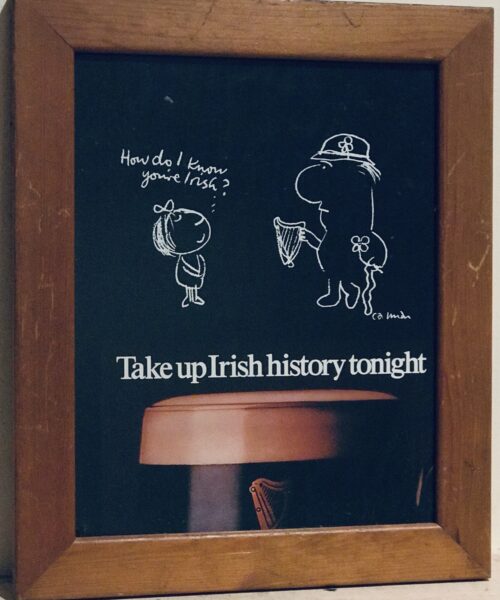

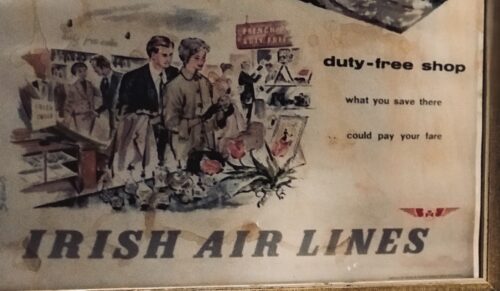

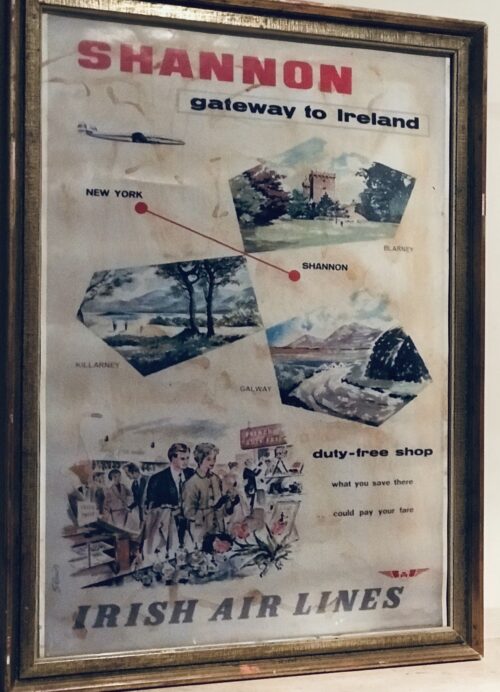

Classic Cork Distilleries Whisky Ltd advert Origins: Bandon Co Cork Dimensions : 44cm x 53cmOrigin:Co Tipperary Dimensions :25cm x 30cm

Classic Cork Distilleries Whisky Ltd advert Origins: Bandon Co Cork Dimensions : 44cm x 53cmOrigin:Co Tipperary Dimensions :25cm x 30cm

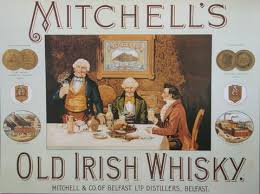

Paddy is a brand of blended Irish whiskey produced by Irish Distillers, at the Midleton distillery in County Cork, on behalf of Sazerac, a privately held American company. Irish distillers owned the brand until its sale to Sazerac in 2016. As of 2016, Paddy is the fourth largest selling Irish whiskey in the WorldHistory The Cork Distilleries Company was founded in 1867 to merge four existing distilleries in Cork city (the North Mall, the Green, Watercourse Road, and Daly's) under the control of one group.A fifth distillery, the Midleton distillery, joined the group soon after in 1868. In 1882, the company hired a young Corkman called Paddy Flaherty as a salesman. Flaherty travelled the pubs of Cork marketing the company's unwieldy named "Cork Distilleries Company Old Irish Whiskey".His sales techniques (which including free rounds of drinks for customers) were so good, that when publicans ran low on stock they would write the distillery to reorder cases of "Paddy Flaherty's whiskey". In 1912, with his name having become synonymous with the whiskey, the distillery officially renamed the whiskey Paddy Irish Whiskey in his honour. In 1920s and 1930s in Ireland, whiskey was sold in casks from the distillery to wholesalers, who would in turn sell it on to publicans.To prevent fluctuations in quality due to middlemen diluting their casks, Cork Distilleries Company decided to bottle their own whiskey known as Paddy, becoming one of the first to do so. In 1988, following an unsolicited takeover offer by Grand Metropolitan, Irish Distillers approached Pernod Ricard and subsequently became a subsidiary of the French drinks conglomerate, following a friendly takeover bid. In 2016, Pernod Ricard sold the Paddy brand to Sazerac, a privately held American firm for an undisclosed fee. Pernod Ricard stated that the sale was in order "simplify" their portfolio, and allow for more targeted investment in their other Irish whiskey brands, such as Jameson and Powers. At the time of the sale, Paddy was the fourth largest selling Irish whiskey brand in the world, with sales of 200,000 9-litre cases per annum, across 28 countries worldwide. Paddy whiskey is distilled three times and matured in oak casks for up to seven years.Compared with other Irish whiskeys, Paddy has a comparatively low pot still content and a high malt content in its blend. Jim Murray, author of the Whiskey bible, has rated Paddy as "one of the softest of all Ireland's whiskeys". -

Carrolls Number 1 Virginia Cigarettes Retro advert fashioned from the blood, sweat,tears and spillage of a well used Irish Bar Trays & enamel signs.Using high quality reprographics we have brought every scratch,dent and mark back to life in the shape of this unique series of prints. Dimensions : 35cm x 48cm GlazedP. J. Carroll & Company Limited, often called Carroll's, is a tobacco company in Republic of Ireland. It is Ireland's oldest tobacco manufacturer and is now a subsidiary of British American Tobacco Plc.Its cigarette brands were among the best selling in Ireland in the twentieth century. Its factory was for decades the largest employer in Dundalk. Patrick James Carroll (b. 1803) completed his apprenticeship as a tobacconist in 1824 and opened a shop in Dundalk, later also manufacturing cigars.Patrick James moved to Liverpool in the 1850s. His son Vincent Stannus Carroll expanded the firm in the later 19th century.His son James Marmion Carroll moved to a house outside Dundalk.A second factory was opened, in Liverpool, in 1923. The company went public in 1934. A purpose-built factory opened in 1970. Designed by Ronnie Tallon of Michael Scott and Partners, it was described by Frank McDonald as "way ahead of anything else in Ireland at the time". In 1974 to mark the 150th anniversary of its founding, P.J. Carroll published an illustrated booklet by the writer James Plunkett: P. J. Carroll & Co. Ltd, Dublin & Dundalk - A Retrospect, outlining the development of the company in its historical context. Carroll's was acquired by Rothmans in 1990; Rothmans was acquired by British American Tobacco Plc in 1998. The company's share of the Irish tobacco market is around 17%. In 2002 the Dundalk site was sold for €16.4m to the Department of Education and repurposed for the campus of Dundalk Institute of Technology. Carroll's rented back a small section for its remaining factory operations, until finally ceasing its Dundalk operations in 2008. Carrolls remains an Irish company with deep connections to hundreds of retirees and nearly 40 staff based in their Dublin offices. PJ Carroll agrees that the Government should regulate on smoking and health issues; this regulation should be informed, evidence-based, and proportionate. PJ Carroll and BAT acknowledge that smoking is a cause of various serious and fatal diseases, including lung cancer, emphysema, chronic bronchitis and cardiovascular diseases. In 2013,some lawmakers suggested PJ Carroll should be prohibited from speaking with lawmakers on the basis of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). PJ Carroll comes under the definition of Tobacco Industry as set out by the FCTC, but the FCTC does not prohibit engagement between tobacco companies and public representatives, but puts in place strict rules relating to transparency.

Carrolls Number 1 Virginia Cigarettes Retro advert fashioned from the blood, sweat,tears and spillage of a well used Irish Bar Trays & enamel signs.Using high quality reprographics we have brought every scratch,dent and mark back to life in the shape of this unique series of prints. Dimensions : 35cm x 48cm GlazedP. J. Carroll & Company Limited, often called Carroll's, is a tobacco company in Republic of Ireland. It is Ireland's oldest tobacco manufacturer and is now a subsidiary of British American Tobacco Plc.Its cigarette brands were among the best selling in Ireland in the twentieth century. Its factory was for decades the largest employer in Dundalk. Patrick James Carroll (b. 1803) completed his apprenticeship as a tobacconist in 1824 and opened a shop in Dundalk, later also manufacturing cigars.Patrick James moved to Liverpool in the 1850s. His son Vincent Stannus Carroll expanded the firm in the later 19th century.His son James Marmion Carroll moved to a house outside Dundalk.A second factory was opened, in Liverpool, in 1923. The company went public in 1934. A purpose-built factory opened in 1970. Designed by Ronnie Tallon of Michael Scott and Partners, it was described by Frank McDonald as "way ahead of anything else in Ireland at the time". In 1974 to mark the 150th anniversary of its founding, P.J. Carroll published an illustrated booklet by the writer James Plunkett: P. J. Carroll & Co. Ltd, Dublin & Dundalk - A Retrospect, outlining the development of the company in its historical context. Carroll's was acquired by Rothmans in 1990; Rothmans was acquired by British American Tobacco Plc in 1998. The company's share of the Irish tobacco market is around 17%. In 2002 the Dundalk site was sold for €16.4m to the Department of Education and repurposed for the campus of Dundalk Institute of Technology. Carroll's rented back a small section for its remaining factory operations, until finally ceasing its Dundalk operations in 2008. Carrolls remains an Irish company with deep connections to hundreds of retirees and nearly 40 staff based in their Dublin offices. PJ Carroll agrees that the Government should regulate on smoking and health issues; this regulation should be informed, evidence-based, and proportionate. PJ Carroll and BAT acknowledge that smoking is a cause of various serious and fatal diseases, including lung cancer, emphysema, chronic bronchitis and cardiovascular diseases. In 2013,some lawmakers suggested PJ Carroll should be prohibited from speaking with lawmakers on the basis of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). PJ Carroll comes under the definition of Tobacco Industry as set out by the FCTC, but the FCTC does not prohibit engagement between tobacco companies and public representatives, but puts in place strict rules relating to transparency.Brands

- "Carrolls Number 1", its first filter cigarette, was launched in 1958.

- "Carrolls Additive Free* Red" and "Carrolls Additive Free* Blue" was launched in 2013 as additive free* cigarettes started to gain popularity across Western Europe. (*No additives in the tobacco blend does NOT mean a less harmful cigarette)

- "Pall Mall" is one of PJ Carroll's strongest growing brands.

- Vogue is PJ Carroll's premium cigarette brand.

- "Major",[4] a full flavor cigarette.

- "Sweet Afton", launched in 1919, was named after "'Afton Waters" by Robert Burns, whose sister Agnes was buried in a graveyard opposite the old Carrolls factory in Church Street, Dundalk.[2]Sweet Afton cigarettes were discontinued in the Autumn of 2011.

Sponsorship[edit]

Carroll's was a major sponsor of sport in Ireland until restrictions were imposed on tobacco advertising. The company had naming rights over the GAA All Stars Awards (1971–78);[8] and Irish showjumping horses of the 1970s and 80s, such as "Carroll's Boomerang".[9] In golf, Carroll's was the sponsor of several professional tournaments including the Carroll's International (1963 to 1974), the Carroll's Number 1 Tournament (1965 to 1968), the Carroll's Irish Match Play Championship (1969 to 1982),[10] and most notably the revived Irish Open from 1975 to 1993. -

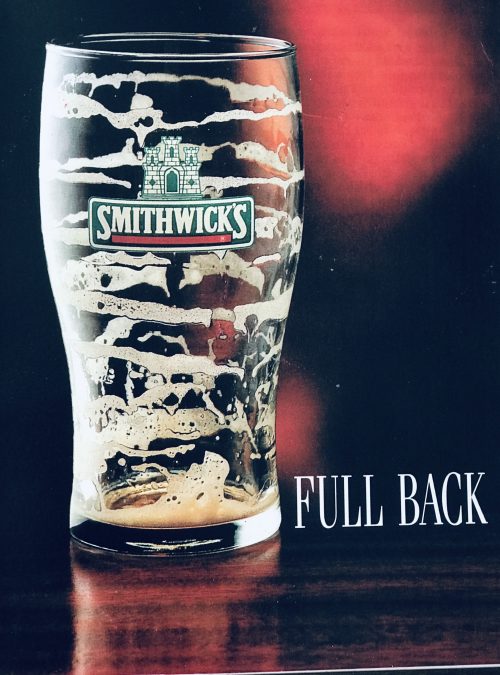

Nice 90s era retro Smithwicks -Full Back -advert run around the time of the old 5 nations Rugby Tournament. Dimensions :35cm x 48cm Glazed Swords Co Dublin Smithwick's brewery was founded in Kilkenny in 1710 by John Smithwick and run by the Smithwick family of Kilkenny until 1965 when it was acquired by Guinness, now part of Diageo. The Kilkenny brewery was shut down in 2013 and production of all Smithwick's and Kilkenny branded beers moved to Dublin; parts of the old brewery are now a "visitor experience". Smithwick's Brewery was founded by John Smithwick in 1710. The brewery is on the site of a Franciscan abbey, where monks had brewed ale since the 14th century, and ruins of the original abbey still remain on its grounds. The old brewery has since been renovated and now hosts "The Smithwick's Experience Kilkenny" visitor attraction and centre. At the time of its closure, it was Ireland's oldest operating brewery. John Smithwick was an orphan who had settled in Kilkenny. Shortly after his arrival, Smithwick went into the brewing business with Richard Cole on a piece of land that Cole had leased from the Duke of Ormond in 1705. Five years later, John Smithwick became the owner of the land. The brewery stayed small, servicing a loyal local following while John Smithwick diversified. Following John Smithwick's death, the brewery temporarily fell out of family hands. John Smithwick's great-grandson, Edmond bought the brewery land back freehold and worked to reshape its future. Edmond concentrated on discovering new markets and successfully building export trade. Drinkers in England, Scotland and Wales developed a taste for Smithwick's brews and output increased fivefold. As a result of substantial contributions made to St Mary's Cathedral, Edmond became great friends with Irish liberal Daniel O'Connell, who later became godfather to one of his sons. Edmond Smithwick became well known and respected by the people of Kilkenny who elected him town mayor four times. In 1800, export sales began to fall and the brewing industry encountered difficulty. To combat this, the Smithwick family increased production in their maltings, began selling mineral water and delivered butter with the ale from the back of their drays. By 1900, output was at an all-time low and the then owner James Smithwick was advised by auditors to shut the doors of the brewery. Instead, James reduced the range of beers they produced and set out to find new markets. He secured military contracts and soon after saw output increase again. James' son, Walter, took control in 1930 and steered the brewery to success through the hardships of both World War II and increasingly challenging weather conditions. By January 1950, Smithwick's was exporting ale to Boston. Smithwick's was purchased from Walter Smithwick in 1965 by Guinness and is now, along with Guinness, part of Diageo. Together, Guinness & Co. and Smithwick's developed and launched Smithwick's Draught Ale in 1966. By 1979, half a million barrels were sold each year. In 1980, Smithwick's began exporting to France. In 1993, Smithwick's Draught became Canada's leading imported ale. By 2010, Smithwick's continued to be brewed in Dundalk and Kilkenny with tankers sent to Dublin to be kegged for the on trade market. Cans and bottles were packaged by IBC in Belfast. Production in the Kilkenny brewery finished on 31 December 2013 and Smithwick's brands are now produced in the Diageo St.James's Gate brewery in Dublin. In 2017 Walter Smithwick's son, Paul, launched Sullivan's Ale with his son, Daniel, which has its home in Kilkenny. The original Kilkenny site was sold to Kilkenny County Council, with a small portion of the site dedicated to the opening of a visitor's centre, the "Smithwick's Experience Kilkenny".

Nice 90s era retro Smithwicks -Full Back -advert run around the time of the old 5 nations Rugby Tournament. Dimensions :35cm x 48cm Glazed Swords Co Dublin Smithwick's brewery was founded in Kilkenny in 1710 by John Smithwick and run by the Smithwick family of Kilkenny until 1965 when it was acquired by Guinness, now part of Diageo. The Kilkenny brewery was shut down in 2013 and production of all Smithwick's and Kilkenny branded beers moved to Dublin; parts of the old brewery are now a "visitor experience". Smithwick's Brewery was founded by John Smithwick in 1710. The brewery is on the site of a Franciscan abbey, where monks had brewed ale since the 14th century, and ruins of the original abbey still remain on its grounds. The old brewery has since been renovated and now hosts "The Smithwick's Experience Kilkenny" visitor attraction and centre. At the time of its closure, it was Ireland's oldest operating brewery. John Smithwick was an orphan who had settled in Kilkenny. Shortly after his arrival, Smithwick went into the brewing business with Richard Cole on a piece of land that Cole had leased from the Duke of Ormond in 1705. Five years later, John Smithwick became the owner of the land. The brewery stayed small, servicing a loyal local following while John Smithwick diversified. Following John Smithwick's death, the brewery temporarily fell out of family hands. John Smithwick's great-grandson, Edmond bought the brewery land back freehold and worked to reshape its future. Edmond concentrated on discovering new markets and successfully building export trade. Drinkers in England, Scotland and Wales developed a taste for Smithwick's brews and output increased fivefold. As a result of substantial contributions made to St Mary's Cathedral, Edmond became great friends with Irish liberal Daniel O'Connell, who later became godfather to one of his sons. Edmond Smithwick became well known and respected by the people of Kilkenny who elected him town mayor four times. In 1800, export sales began to fall and the brewing industry encountered difficulty. To combat this, the Smithwick family increased production in their maltings, began selling mineral water and delivered butter with the ale from the back of their drays. By 1900, output was at an all-time low and the then owner James Smithwick was advised by auditors to shut the doors of the brewery. Instead, James reduced the range of beers they produced and set out to find new markets. He secured military contracts and soon after saw output increase again. James' son, Walter, took control in 1930 and steered the brewery to success through the hardships of both World War II and increasingly challenging weather conditions. By January 1950, Smithwick's was exporting ale to Boston. Smithwick's was purchased from Walter Smithwick in 1965 by Guinness and is now, along with Guinness, part of Diageo. Together, Guinness & Co. and Smithwick's developed and launched Smithwick's Draught Ale in 1966. By 1979, half a million barrels were sold each year. In 1980, Smithwick's began exporting to France. In 1993, Smithwick's Draught became Canada's leading imported ale. By 2010, Smithwick's continued to be brewed in Dundalk and Kilkenny with tankers sent to Dublin to be kegged for the on trade market. Cans and bottles were packaged by IBC in Belfast. Production in the Kilkenny brewery finished on 31 December 2013 and Smithwick's brands are now produced in the Diageo St.James's Gate brewery in Dublin. In 2017 Walter Smithwick's son, Paul, launched Sullivan's Ale with his son, Daniel, which has its home in Kilkenny. The original Kilkenny site was sold to Kilkenny County Council, with a small portion of the site dedicated to the opening of a visitor's centre, the "Smithwick's Experience Kilkenny".Smithwick Family

Walter and Eileen Smithwick had 6 children; Judge Peter Smithwick, Michael, Anne, Judy, Paul and John. Judge Peter Smithwick (born 1937) is an Irish judge, and Chairman and Sole Member of the Smithwick Tribunal, a Tribunal of Inquiry into the events surrounding the killing of Chief Superintendent Harry Breen and Superintendent Robert Buchanan of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). Paul Smithwick (born 1943) launched Sullivan's Ale in 2016 with his son Daniel. His eldest daughter Emma Smithwick is a well-known TV producer in London. His daughter Georgina is a technology entrepreneur, named by Sunday Times as Top 100 Innovators in Great Britain.Sullivan's Brewery

In the Old Kilkenny Review, year unknown, Peter Smithwick, K.M., Solicitor, wrote that the tradition in Kilkenny is that Sullivan's Brewery was founded in 1702 by Daniel Sullivan, a Protestant, who bought property in trust for Pierse Bryan of Jenkinstown, a Catholic who was prohibited by the Penal Laws from buying land. The property, on the West side of High Street, "standing backwards in James's Street", is believed to have been the site of Sullivan's Brewery, the forerunner of Smithwicks. -

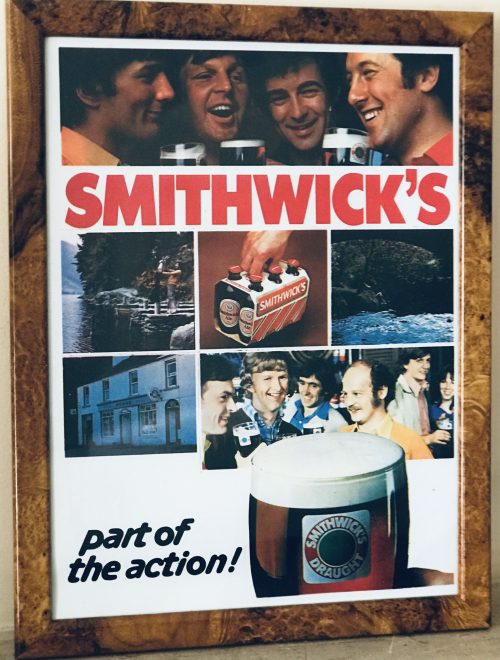

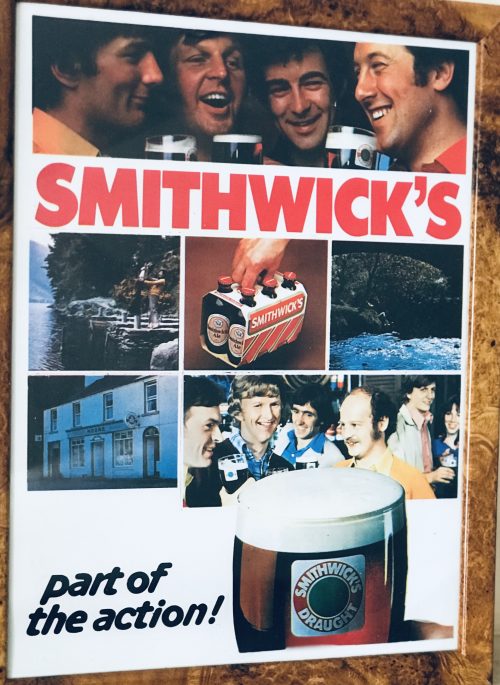

Nice 1970s era retro Smithwicks -part of the action-advert. Dimensions :35cm x 48cm Glazed Smithwick's brewery was founded in Kilkenny in 1710 by John Smithwick and run by the Smithwick family of Kilkenny until 1965 when it was acquired by Guinness, now part of Diageo. The Kilkenny brewery was shut down in 2013 and production of all Smithwick's and Kilkenny branded beers moved to Dublin; parts of the old brewery are now a "visitor experience". Smithwick's Brewery was founded by John Smithwick in 1710. The brewery is on the site of a Franciscan abbey, where monks had brewed ale since the 14th century, and ruins of the original abbey still remain on its grounds. The old brewery has since been renovated and now hosts "The Smithwick's Experience Kilkenny" visitor attraction and centre. At the time of its closure, it was Ireland's oldest operating brewery. John Smithwick was an orphan who had settled in Kilkenny. Shortly after his arrival, Smithwick went into the brewing business with Richard Cole on a piece of land that Cole had leased from the Duke of Ormond in 1705. Five years later, John Smithwick became the owner of the land. The brewery stayed small, servicing a loyal local following while John Smithwick diversified. Following John Smithwick's death, the brewery temporarily fell out of family hands. John Smithwick's great-grandson, Edmond bought the brewery land back freehold and worked to reshape its future. Edmond concentrated on discovering new markets and successfully building export trade. Drinkers in England, Scotland and Wales developed a taste for Smithwick's brews and output increased fivefold. As a result of substantial contributions made to St Mary's Cathedral, Edmond became great friends with Irish liberal Daniel O'Connell, who later became godfather to one of his sons. Edmond Smithwick became well known and respected by the people of Kilkenny who elected him town mayor four times. In 1800, export sales began to fall and the brewing industry encountered difficulty. To combat this, the Smithwick family increased production in their maltings, began selling mineral water and delivered butter with the ale from the back of their drays. By 1900, output was at an all-time low and the then owner James Smithwick was advised by auditors to shut the doors of the brewery. Instead, James reduced the range of beers they produced and set out to find new markets. He secured military contracts and soon after saw output increase again. James' son, Walter, took control in 1930 and steered the brewery to success through the hardships of both World War II and increasingly challenging weather conditions. By January 1950, Smithwick's was exporting ale to Boston. Smithwick's was purchased from Walter Smithwick in 1965 by Guinness and is now, along with Guinness, part of Diageo. Together, Guinness & Co. and Smithwick's developed and launched Smithwick's Draught Ale in 1966. By 1979, half a million barrels were sold each year. In 1980, Smithwick's began exporting to France. In 1993, Smithwick's Draught became Canada's leading imported ale. By 2010, Smithwick's continued to be brewed in Dundalk and Kilkenny with tankers sent to Dublin to be kegged for the on trade market. Cans and bottles were packaged by IBC in Belfast. Production in the Kilkenny brewery finished on 31 December 2013 and Smithwick's brands are now produced in the Diageo St.James's Gate brewery in Dublin. In 2017 Walter Smithwick's son, Paul, launched Sullivan's Ale with his son, Daniel, which has its home in Kilkenny. The original Kilkenny site was sold to Kilkenny County Council, with a small portion of the site dedicated to the opening of a visitor's centre, the "Smithwick's Experience Kilkenny".

Nice 1970s era retro Smithwicks -part of the action-advert. Dimensions :35cm x 48cm Glazed Smithwick's brewery was founded in Kilkenny in 1710 by John Smithwick and run by the Smithwick family of Kilkenny until 1965 when it was acquired by Guinness, now part of Diageo. The Kilkenny brewery was shut down in 2013 and production of all Smithwick's and Kilkenny branded beers moved to Dublin; parts of the old brewery are now a "visitor experience". Smithwick's Brewery was founded by John Smithwick in 1710. The brewery is on the site of a Franciscan abbey, where monks had brewed ale since the 14th century, and ruins of the original abbey still remain on its grounds. The old brewery has since been renovated and now hosts "The Smithwick's Experience Kilkenny" visitor attraction and centre. At the time of its closure, it was Ireland's oldest operating brewery. John Smithwick was an orphan who had settled in Kilkenny. Shortly after his arrival, Smithwick went into the brewing business with Richard Cole on a piece of land that Cole had leased from the Duke of Ormond in 1705. Five years later, John Smithwick became the owner of the land. The brewery stayed small, servicing a loyal local following while John Smithwick diversified. Following John Smithwick's death, the brewery temporarily fell out of family hands. John Smithwick's great-grandson, Edmond bought the brewery land back freehold and worked to reshape its future. Edmond concentrated on discovering new markets and successfully building export trade. Drinkers in England, Scotland and Wales developed a taste for Smithwick's brews and output increased fivefold. As a result of substantial contributions made to St Mary's Cathedral, Edmond became great friends with Irish liberal Daniel O'Connell, who later became godfather to one of his sons. Edmond Smithwick became well known and respected by the people of Kilkenny who elected him town mayor four times. In 1800, export sales began to fall and the brewing industry encountered difficulty. To combat this, the Smithwick family increased production in their maltings, began selling mineral water and delivered butter with the ale from the back of their drays. By 1900, output was at an all-time low and the then owner James Smithwick was advised by auditors to shut the doors of the brewery. Instead, James reduced the range of beers they produced and set out to find new markets. He secured military contracts and soon after saw output increase again. James' son, Walter, took control in 1930 and steered the brewery to success through the hardships of both World War II and increasingly challenging weather conditions. By January 1950, Smithwick's was exporting ale to Boston. Smithwick's was purchased from Walter Smithwick in 1965 by Guinness and is now, along with Guinness, part of Diageo. Together, Guinness & Co. and Smithwick's developed and launched Smithwick's Draught Ale in 1966. By 1979, half a million barrels were sold each year. In 1980, Smithwick's began exporting to France. In 1993, Smithwick's Draught became Canada's leading imported ale. By 2010, Smithwick's continued to be brewed in Dundalk and Kilkenny with tankers sent to Dublin to be kegged for the on trade market. Cans and bottles were packaged by IBC in Belfast. Production in the Kilkenny brewery finished on 31 December 2013 and Smithwick's brands are now produced in the Diageo St.James's Gate brewery in Dublin. In 2017 Walter Smithwick's son, Paul, launched Sullivan's Ale with his son, Daniel, which has its home in Kilkenny. The original Kilkenny site was sold to Kilkenny County Council, with a small portion of the site dedicated to the opening of a visitor's centre, the "Smithwick's Experience Kilkenny".Smithwick Family

Walter and Eileen Smithwick had 6 children; Judge Peter Smithwick, Michael, Anne, Judy, Paul and John. Judge Peter Smithwick (born 1937) is an Irish judge, and Chairman and Sole Member of the Smithwick Tribunal, a Tribunal of Inquiry into the events surrounding the killing of Chief Superintendent Harry Breen and Superintendent Robert Buchanan of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). Paul Smithwick (born 1943) launched Sullivan's Ale in 2016 with his son Daniel. His eldest daughter Emma Smithwick is a well-known TV producer in London. His daughter Georgina is a technology entrepreneur, named by Sunday Times as Top 100 Innovators in Great Britain.Sullivan's Brewery

In the Old Kilkenny Review, year unknown, Peter Smithwick, K.M., Solicitor, wrote that the tradition in Kilkenny is that Sullivan's Brewery was founded in 1702 by Daniel Sullivan, a Protestant, who bought property in trust for Pierse Bryan of Jenkinstown, a Catholic who was prohibited by the Penal Laws from buying land. The property, on the West side of High Street, "standing backwards in James's Street", is believed to have been the site of Sullivan's Brewery, the forerunner of Smithwicks. -

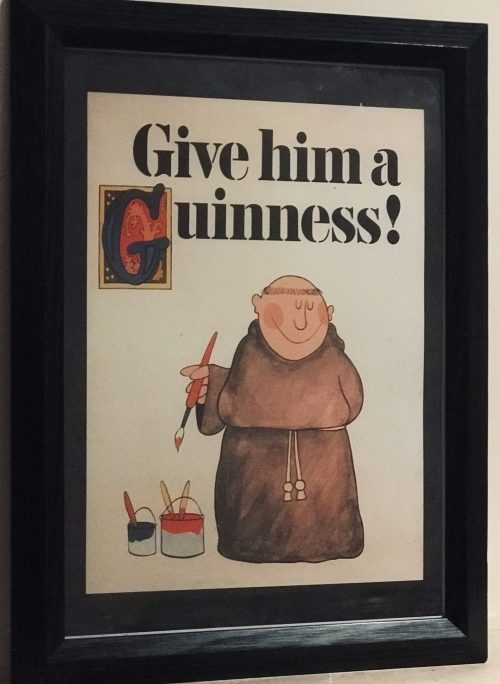

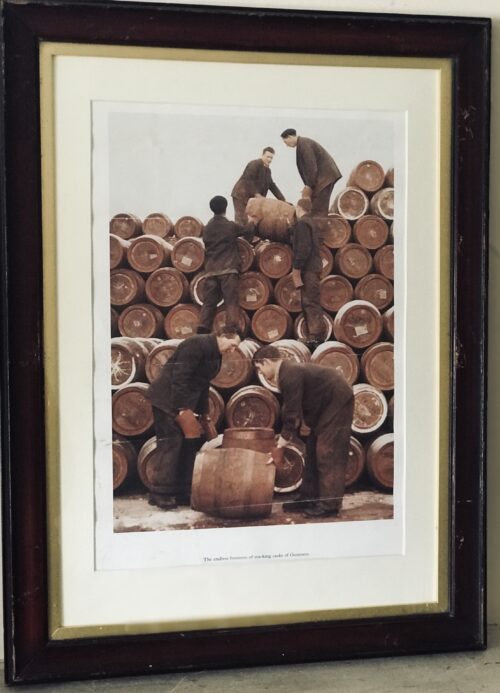

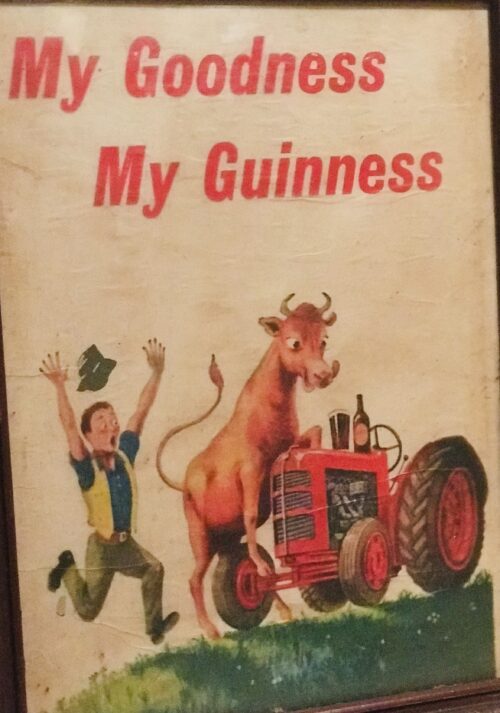

The well known Guinness drinking Monk with easel advert from the Guinness archives. Dimensions : 35cm x 48cm Glazed Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm

The well known Guinness drinking Monk with easel advert from the Guinness archives. Dimensions : 35cm x 48cm Glazed Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm -

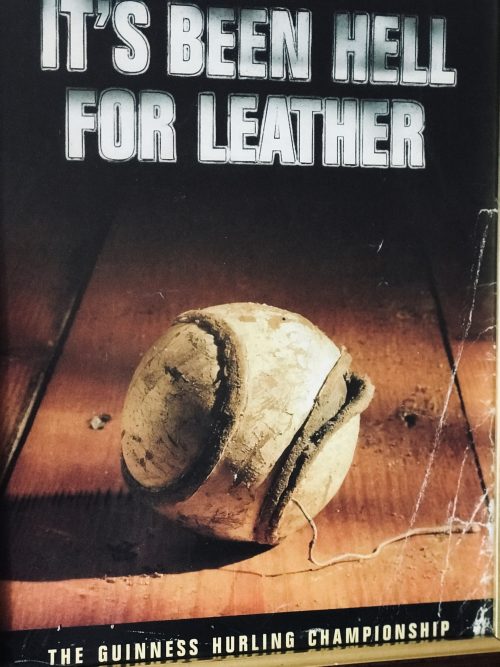

Its been hell for leather Guinness Hurling advert from the 90s. Dromkeen Co Limerick Dimensions : 52cm x 40cm Glazed " It was not until 1994 that the GAA decided that the football championship would benefit from bringing on a title sponsor in Bank of Ireland. Although an equivalent offer had been on the table for the hurling championship, Central Council pushed the plate away.Though the name of the potential sponsor wasn’t explicitly made public, everyone knew it was Guinness. More to the point, everyone knew why Central Council wouldn’t bite. As Mulvihill himself noted in his report to Congress, the offer was declined on the basis that “Central Council did not want an alcoholic drinks company associated with a major GAA competition”. As it turned out, Central Council had been deadlocked on the issue and it was the casting vote of then president Peter Quinn that put the kibosh on a deal with Guinness. Mulvihill’s disappointment was far from hidden, since he saw the wider damage caused by turning up the GAA nose at Guinness’s advances. “The unfortunate aspect of the situation,” he wrote, “is that hurling needs support on the promotion of the game much more than football.” Though it took the point of a bayonet to make them go for it, the GAA submitted in the end and on the day after the league final in 1995 , a three-year partnership with Guinness was announced. The deal would be worth £1 million a year, with half going to the sport and half going to the competition in the shape of marketing. That last bit was key. Guinness came up with a marketing campaign that fairly scorched across the general consciousness. Billboards screeched out slogans that feel almost corny at this remove but made a huge impact at the same time . This man can level whole counties in one second flat. This man can reach speeds of 100mph. This man can break hearts at 70 yards Its been Hell for Leather. Of course, all the marketing in the world can only do so much. Without a story to go alongside, the Guinness campaign might be forgotten now – or worse, remembered as an overblown blast of hot air dreamed up in some modish ad agency above in Dublin.Until the Clare hurlers came along and changed everything." Malachy Clerkin Irish Times GAA Correspondent Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm

Its been hell for leather Guinness Hurling advert from the 90s. Dromkeen Co Limerick Dimensions : 52cm x 40cm Glazed " It was not until 1994 that the GAA decided that the football championship would benefit from bringing on a title sponsor in Bank of Ireland. Although an equivalent offer had been on the table for the hurling championship, Central Council pushed the plate away.Though the name of the potential sponsor wasn’t explicitly made public, everyone knew it was Guinness. More to the point, everyone knew why Central Council wouldn’t bite. As Mulvihill himself noted in his report to Congress, the offer was declined on the basis that “Central Council did not want an alcoholic drinks company associated with a major GAA competition”. As it turned out, Central Council had been deadlocked on the issue and it was the casting vote of then president Peter Quinn that put the kibosh on a deal with Guinness. Mulvihill’s disappointment was far from hidden, since he saw the wider damage caused by turning up the GAA nose at Guinness’s advances. “The unfortunate aspect of the situation,” he wrote, “is that hurling needs support on the promotion of the game much more than football.” Though it took the point of a bayonet to make them go for it, the GAA submitted in the end and on the day after the league final in 1995 , a three-year partnership with Guinness was announced. The deal would be worth £1 million a year, with half going to the sport and half going to the competition in the shape of marketing. That last bit was key. Guinness came up with a marketing campaign that fairly scorched across the general consciousness. Billboards screeched out slogans that feel almost corny at this remove but made a huge impact at the same time . This man can level whole counties in one second flat. This man can reach speeds of 100mph. This man can break hearts at 70 yards Its been Hell for Leather. Of course, all the marketing in the world can only do so much. Without a story to go alongside, the Guinness campaign might be forgotten now – or worse, remembered as an overblown blast of hot air dreamed up in some modish ad agency above in Dublin.Until the Clare hurlers came along and changed everything." Malachy Clerkin Irish Times GAA Correspondent Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm -

Superb print of the 1908 Clare Hurling Team who won the Croke Cup. Origins : Ennistymon Co Clare Dimensions: 33cm x 40cm. Glazed

Superb print of the 1908 Clare Hurling Team who won the Croke Cup. Origins : Ennistymon Co Clare Dimensions: 33cm x 40cm. Glazed

Dimensions ; 30cm x 40cmDr Croke Cup Medal, 1908 The Dr Croke Cup was a second inter-county competition instituted in both hurling and football in 1896. Clare was the first winner of the Dr Croke Cup for Hurling in 1896. This medal was won by Ned Grace, one of seven O’Callaghan’s Mills players on the Croke Cup winning Hurling team of 1908. -

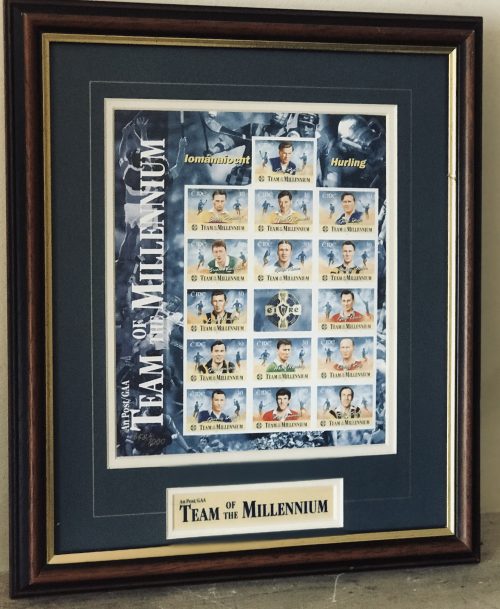

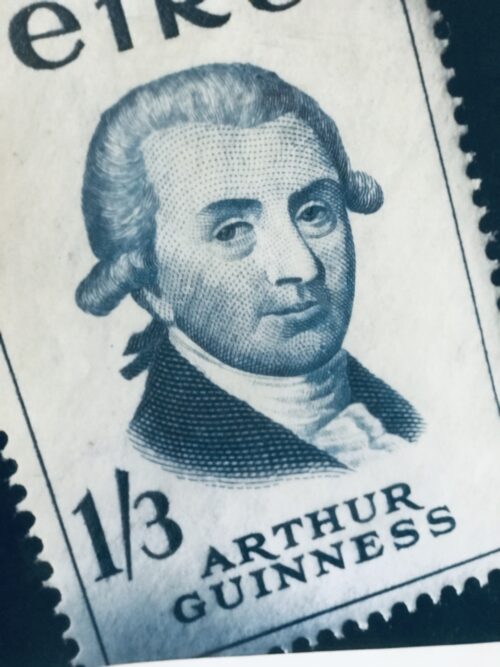

36cm x 29cm The An Post GAA Hurling Team of the Millennium was chosen in 2000 to comprise, as a fifteen-member side divided as one goalkeeper, three full-backs, three half-backs, two midfielders, three half-forwards and three full-forwards, the best hurling team of all-time. The team, announced by GAA President Seán McCague on 24 July 2000 at a special function in Croke Park, was selected by a special committee, comprising five past GAA presidents - Joe McDonagh, Con Murphy, Paddy Buggy, Pat Fanning and Séamus Ó Riain - as well as GAA director-general Liam Mulvihill and four Gaelic games journalists: Paddy Downey, Mick Dunne, Seán Óg Ó Ceallacháin and Jim O'Sullivan. The initiative was sponsored by An Post, who issued special commemorative stamps of the millennium team members.

36cm x 29cm The An Post GAA Hurling Team of the Millennium was chosen in 2000 to comprise, as a fifteen-member side divided as one goalkeeper, three full-backs, three half-backs, two midfielders, three half-forwards and three full-forwards, the best hurling team of all-time. The team, announced by GAA President Seán McCague on 24 July 2000 at a special function in Croke Park, was selected by a special committee, comprising five past GAA presidents - Joe McDonagh, Con Murphy, Paddy Buggy, Pat Fanning and Séamus Ó Riain - as well as GAA director-general Liam Mulvihill and four Gaelic games journalists: Paddy Downey, Mick Dunne, Seán Óg Ó Ceallacháin and Jim O'Sullivan. The initiative was sponsored by An Post, who issued special commemorative stamps of the millennium team members.Controversy

While universal agreement on such a team would prove impossible, the selection committee came in for some criticism regarding omissions and changes from the earlier GAA Hurling Team of the Century. Kilkenny's D. J. Carey was seen as a shock omission from the team. As the holder of a then record seven All-Stars, Carey, whose inter-county career began in 1989, was seen as one of the greatest goal-scorers of his era and was hotly tipped to get one of the half-forward spots for which he was nominated. The 1990s were regarded as a golden age of hurling with many new teams emerging, however, this was not reflected in the team. Clare's Brian Lohan had been tipped for full-back but Wexford's Nick O'Donnell held on. There were no places for any of the Clare team that emerged to win two championships in the nineties. Brian Whelehan was the only player from the previous 20 years to make the team. An absence of players from Galway also sparked off major controversy in that county where the selection committee were accused of belittling the county by not recognising any of its heroes. There was anger too in Wexford over the dropping of full-forward Nicky Rackard from the Team of the Century. Former midfielder Dave Bernie, who won an All-Ireland medal in 1968, when Rackard was a selector, said Wexford fans were stunned by the news he had not been included. -