27cm x 27cm Castlegregory Co Kerry

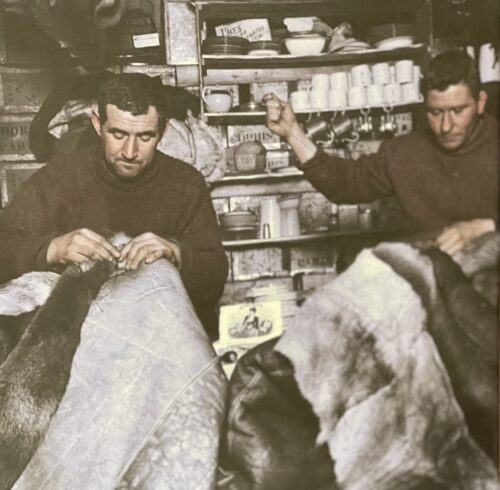

Fine framed print of the legendary Irish Antarctic explorer and hero,Tom Crean mending blankets with his colleague on Shackleton's final Expedition

Thomas Crean (

c. 16 February 1877

– 27 July 1938) was an Irish

seaman and Antarctic

explorer who was awarded the

Albert Medal for Lifesaving.

Crean was a member of three major expeditions to Antarctica during the

Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, including

Robert Falcon Scott's 1911–1913

Terra Nova Expedition. This saw the race to reach the

South Pole lost to

Roald Amundsen and ended in the deaths of Scott and his party. During the expedition, Crean's 35-statute-mile (56 km) solo walk across the

Ross Ice Shelf to save the life of

Edward Evans led to him receiving the Albert Medal.

Crean left the family farm near

Annascaul, in County Kerry, to enlist in the

Royal Navy at age 16. In 1901, while serving on

Ringarooma in New Zealand, he volunteered to join Scott's 1901–1904

Discovery Expedition to Antarctica, thus beginning his exploring career.

After his experience on the

Terra Nova, Crean's third and final Antarctic venture was as second officer on

Ernest Shackleton's

Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. After the ship

Endurance became beset in the pack ice and sank, Crean and the ship's company spent 492 days drifting on the ice before undertaking a journey in the ship's lifeboats to

Elephant Island. He was a member of the crew which made a

small-boat journey of 800 nautical miles (1,500 km) from Elephant Island to

South Georgia Island to seek aid for the stranded party.

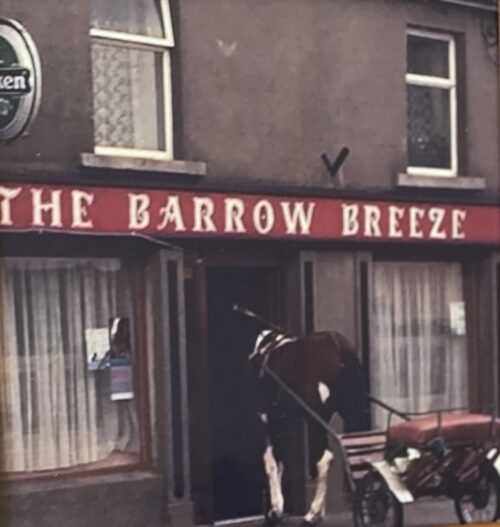

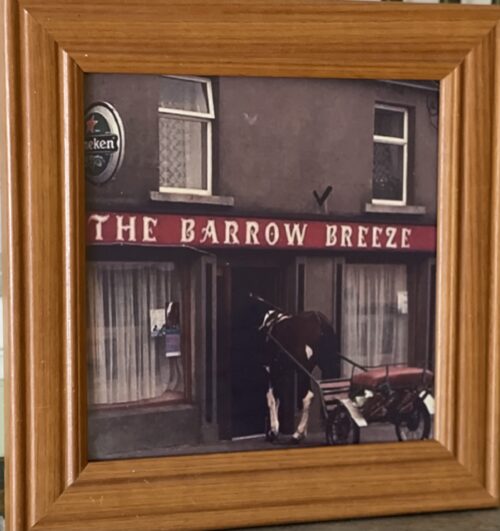

After retiring from the navy on health grounds in 1920, Crean ran his pub the

South Pole Inn in County Kerry with his wife and daughters. He died in 1938.

Crean was born around 16 February 1877

in the farming area of Gurtuchrane near the village of

Annascaul on

Corca Dhuibhne in

County Kerry, Ireland, to Patrick and Catherine (née Courtney) Crean. One of 11 siblings with 7 brothers and 3 sisters. He attended the local Catholic school (at nearby Brackluin), leaving at the age of 12 to help on the family farm. Many sources, including Smith, give Crean's date of birth as 20 July 1877,

but more recent scholarship demonstrates this is unlikely given parish records.

At the age of 16, he enlisted in the

Royal Navy at the naval station in nearby Minard Inlet, possibly after an argument with his father.

His enlistment as a

boy second class is recorded in Royal Navy records on 10 July 1893.

Crean's initial naval apprenticeship was aboard the training ship

Impregnable at

Devonport. In November 1894, he was transferred to

Devastation. In December 1894, Crean was posted to HMS Wild Swan a screw sloop as the ship headed to South America to join the Pacific Station. In 1895, Crean was serving in the Americas aboard

Royal Arthur, the flagship assigned to the Pacific squadron’s base at Esquimalt in Canada. He was by this time,

rated an

ordinary seaman. Less than a year later, while serving a second term of service aboard

Wild Swan he was rated an

able seaman.

He later joined the Navy's torpedo school ship,

Defiance. By 1899, Crean had advanced to the rate of

petty officer, second class and was serving in

Vivid.

In 1900, Crean was ledgered to the cruiser

HMS Ringarooma, which was part of the Royal Navy's Australian Squadron based in Sydney.

On 18 December 1901, he was demoted from petty officer to able seaman for an unspecified misdemeanour.

In December 1901, the

Ringarooma was ordered to assist Robert Falcon Scott's ship

Discovery when it was docked at

Lyttelton Harbour awaiting to departure to Antarctica. When an able seaman of Scott's ship deserted after striking a petty officer, a replacement was required; Crean volunteered, and was accepted.

Discovery Expedition, 1901–1904

Aerial view of Hut Point, McMurdo Sound, Antarctica – the location of

Discovery's base, in 1902–04

Discovery sailed to the Antarctic on 21 December 1901, and seven weeks later, on 8 February 1902, arrived in

McMurdo Sound, where she anchored at a spot which was later designated "Hut Point".

Here the men established the base from which they would launch scientific and exploratory sledging journeys. Crean proved to be one of the most efficient

man-haulers in the party; over the expedition as a whole, only seven of the 48-member party logged more time in harness than Crean's 149 days.

]Crean had a good sense of humour and was well liked by his companions. Scott's second-in-command,

Albert Armitage, wrote in his book

Two Years in the Antarctic that "Crean was an Irishman with a fund of wit and an even temper which nothing disturbed."

Crean accompanied Lieutenant

Michael Barne on three sledging trips across the Ross Ice Shelf, then known as the "Great Ice Barrier". These included the 12-man party led by Barne which set out on 30 October 1902 to lay depots in support of the main southern journey undertaken by Scott, Shackleton and

Edward Wilson. On 11 November the Barne party passed the previous

furthest south mark,

set by

Carsten Borchgrevink in 1900 at 78°50'S, a record which they held briefly until the southern party itself passed it on its way to an eventual 82°17'S.

During the Antarctic winter of 1902

Discovery became locked in the ice. Efforts to free her during the summer of 1902–03 failed, and although some of the expedition's members (including

Ernest Shackleton) left in a relief ship, Crean and the majority of the party remained in the Antarctic until the ship was finally freed in February 1904.

After returning to regular naval duty, Crean was promoted to petty officer, first class, on Scott's recommendation.

Between expeditions, 1904–1910

Crean came back to regular duty at the naval base at

Chatham, Kent, serving first in

Pembroke in 1904 and later transferring to the torpedo school on

Vernon. Crean had caught Captain Scott's attention with his attitude and work ethic on the Discovery Expedition, and in 1906 Scott requested that Crean join him on

Victorious.

Over the next few years, Crean followed Scott successively to

Albemarle,

Essex and

Bulwark.

By 1907, Scott was planning his second expedition to the Antarctic. Meanwhile, Ernest Shackleton's

Nimrod Expedition, 1907–09, despite reaching a new furthest south record of 88°23'S, had failed to reach the South Pole.

Scott was with Crean when the news of Shackleton's near miss became public; it is recorded that Scott observed to Crean: "I think we'd better have a shot next."

Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–1913

Scott's polar party at 87°S, 31 December 1911, before Crean's return with the last supporting party

Scott held Crean in high regard,

so he was among the first people recruited for the Terra Nova Expedition, which set out for the Antarctic in June 1910, and one of the few men in the party with previous polar experience.

After the expedition's arrival in McMurdo Sound in January 1911, Crean was as part of the 13-man team who established "One Ton Depot",130 statute miles (210 km) from

Hut Point.

so named because of the large amount of food and equipment cached there on the projected route to the South Pole. Returning from the depot to base camp at

Cape Evans, Crean, accompanied by

Apsley Cherry-Garrard and

Henry "Birdie" Bowers, experienced near-disaster when camping on unstable sea ice. During the night the ice broke up, leaving the men adrift on an

ice floe and separated from their sledges. Crean probably saved the group's lives, by leaping from floe to floe until he reached the Barrier edge and was able to summon help.

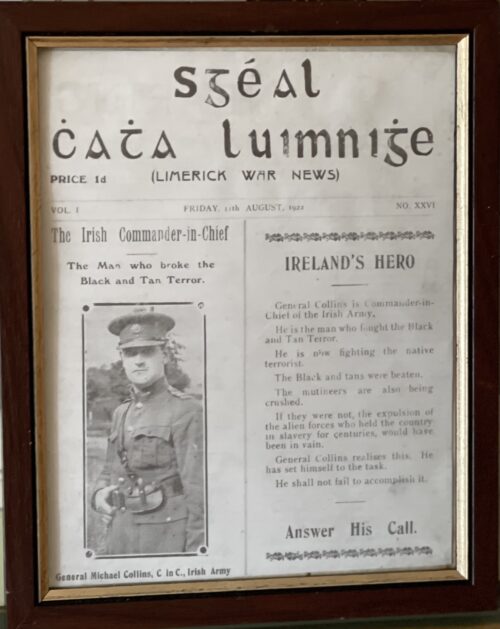

Petty officers

Edgar Evans and Crean mending sleeping bags (May 1911)

Crean departed with Scott in November 1911, for the attempt at the

South Pole. This journey had three stages: 400 statute miles (640 km) across the Barrier, 120 statute miles (190 km) up the heavily crevassed

Beardmore Glacier to an altitude of 10,000 feet (3,000 m) above sea level, and then another 350 statute miles (560 km) to the Pole.

At regular intervals, supporting parties returned to base; Crean was in the final group of eight men that marched on to the polar plateau and reached 87°32'S, 168 statute miles (270 km) from the pole. Here, on 4 January 1912, Scott selected his final polar party: Crean,

William Lashly and

Edward Evans were ordered to return to base, while Scott,

Edgar Evans,

Edward Wilson, Bowers and

Lawrence Oates continued to the pole.

Crean's biographer Michael Smith suggests that Crean would have been a better choice for the polar party than Edgar Evans, who was weakened by a recent hand injury (of which Scott was unaware). Crean, considered one of the toughest men in the expedition, had led a pony across the Barrier and had thus been saved much of the hard labour of man-hauling.

Scott's critical biographer

Roland Huntford records that the surgeon

Edward L Atkinson, who had accompanied the southern party to the top of the Beardmore, had recommended either Lashly or Crean for the polar party rather than Edgar Evans.

Scott in his diary recorded that Crean wept with disappointment at the prospect of having to turn back, so close to the goal.

Tom Crean and Edgar Evans exercising ponies, winter 1911

Soon after heading north on the 700-statute-mile (1,100 km) journey back to base camp, Crean's party lost the trail back to the Beardmore Glacier, and were faced with a long detour around a large

icefall.

With food supplies short, and needing to reach their next supply depot, the group made the decision to slide on their sledge, uncontrolled, down the icefall. The three men slid 2,000 feet (600 m),

dodging crevasses up to 200 feet (61 m) wide, and ending their descent by overturning on an ice ridge.

Evans later wrote: "How we ever escaped entirely uninjured is beyond me to explain".

The gamble at the icefall succeeded, and the men reached their depot two days later.

However, they had great difficulty navigating down the glacier. Lashly wrote: "I cannot describe the maze we got into and the hairbreadth escapes we have had to pass through."

In his attempts to find the way down, Evans removed his goggles and subsequently suffered agonies of

snow blindness that made him into a passenger.

When the party was finally free of the glacier and on the level surface of the Barrier, Evans began to display the first symptoms of

scurvy.

By early February he was in great pain, his joints were swollen and discoloured, and he was passing blood. Through the efforts of Crean and Lashly the group struggled towards One Ton Depot, which they reached on 11 February. At this point Evans collapsed; Crean thought he had died and, according to Evans's account, "his hot tears fell on my face".

With over 100 statute miles (160 km) still to travel before the relative safety of Hut Point, Crean and Lashly began hauling Evans on the sledge, "eking out his life with the last few drops of brandy that they still had with them".

On 18 February they arrived at Corner Camp, still 35 statute miles (56 km) from Hut Point, with only one or two days' food rations left and still four or five days' man-hauling to do. They then decided that Crean should go on alone, to fetch help. With only a little chocolate and three biscuits to sustain him, without a tent or survival equipment,

Crean walked the distance to Hut Point in 18 hours, arriving in a state of collapse to find Atkinson there, with the dog driver Dmtri Gerov.

Crean reached safety just ahead of a fierce blizzard, which probably would have killed him, and which delayed the rescue party by a day and a half.

Atkinson led a successful rescue, and Lashly and Evans were both brought to base camp alive. Crean modestly played down the significance of his feat of endurance. In a rare written account, he wrote in a letter: "So it fell to my lot to do the 30 miles for help, and only a couple of biscuits and a stick of chocolate to do it. Well, sir, I was very weak when I reached the hut."

Scott's party failed to return. The winter of 1912 at Cape Evans was a sombre one, with the knowledge that the polar party had undoubtedly perished.

Frank Debenhamwrote that "in the winter it was once again Crean who was the mainstay for cheerfulness in the now depleted mess deck part of the hut."

In November 1912, Crean was one of the 11-man search party that found the remains of the polar party. On 12 November they spotted a cairn of snow, which proved to be a tent against which the drift had piled up. It contained the bodies of Scott, Wilson, and Bowers.

Crean later wrote, referring to Scott in understated fashion, that he had "lost a good friend".

On 12 February 1913 Crean and the remaining crew of the

Terra Nova arrived in

Lyttelton, New Zealand, and in June the ship returned to Cardiff.

At

Buckingham Palace the surviving members of the expedition were awarded

Polar Medals by

King George and

Prince Louis of Battenberg, the

First Sea Lord.

Crean and Lashly were both awarded the

Albert Medal, 2nd Class for saving Evans's life, these were presented by the King at Buckingham Palace on 26 July 1913. Crean was promoted to the rank of

chief petty officer, retroactive to 9 September 1910.

Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (Endurance Expedition), 1914–1917

Members of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition aboard

Endurance, 1914. Crean is second from the left in the first standing row. Shackleton (wearing soft hat) is in the centre of the picture.

In October 1913, a close friend of Captain Scott, Joseph Foster Stackhouse, announced plans for a British Antarctic Expedition with a mission to explore the uncharted coastlines between King Edward VII Land and Graham Land. The expedition was due to depart England in August 1914 aboard

RRS Discovery, the ship of Crean’s first mission to Antarctica. In February 1914, Stackhouse confirmed that Crean was to join the expedition as Boatswain, however, in April 1914, Stackhouse’s plans were postponed. This left Shackleton free to recruit Crean to his expedition which was also scheduled to depart in August 1914.

Shackleton knew Crean well from the Discovery Expedition, and also knew of his exploits on Scott's last expedition. Like Scott, Shackleton trusted Crean:

he was worth, in Shackleton's own word, "trumps".

Crean joined Shackleton's

Imperial Transantarctic Expedition on 25 May 1914, as second officer,

with a varied range of duties. In the absence of a Canadian dog-handling expert who was hired but never appeared, Crean took charge of one of the dog-handling teams,

and was later involved in the care and nurture of the pups born to one of his dogs, Sally, early in the expedition.

On 19 January 1915 the expedition's ship, the

Endurance, was beset in the

Weddell Sea pack ice. In the early efforts to free her, Crean narrowly escaped being crushed by a sudden movement in the ice.

The ship drifted in the ice for months, eventually sinking on 21 November. Shackleton informed the men that they would drag the food, gear, and three lifeboats across the pack ice, to Snow Hill or

Robertson Island, 200 statute miles (320 km) away. Because of uneven ice conditions, pressure ridges, and the danger of ice breakup which could separate the men, they soon abandoned this plan: the men pitched camp and decided to wait. They hoped that the clockwise drift of the pack would carry them 400 statute miles (640 km) to

Paulet Island where they knew there was a hut with emergency supplies.

But the pack ice held firm as it carried the men well past Paulet Island, and did not break up until 9 April. The crew then had to sail and row the three ill-equipped lifeboats through the pack ice to Elephant Island, a trip which lasted five days. Crean and

Hubert Hudson, the navigating officer of the

Endurance, piloted their lifeboat with Crean effectively in charge as Hudson appeared to have suffered a breakdown.

Tom Crean, in full polar travelling gear

Upon reaching Elephant Island, Crean was one of the "four fittest men" detailed by Shackleton to find a safe camping-ground.

Shackleton decided that, rather than waiting for a rescue ship that would probably never arrive, one of the lifeboats should be strengthened so that a crew could sail it to

South Georgia and arrange a rescue. After the party was settled on a penguin

rookeryabove the high-water mark, a group of men led by ship's carpenter

Harry McNish began modifying one of the lifeboats—the

James Caird—in preparation for this journey, which Shackleton would lead.

Frank Wild, who would be in command of the party remaining on Elephant Island, wanted the dependable Crean to stay with him;

Shackleton initially agreed, but changed his mind after Crean begged to be included in the boat's crew of six.

The 800-nautical-mile (1,500 km) boat journey to South Georgia, described by polar historian Caroline Alexander as one of the most extraordinary feats of seamanship and navigation in recorded history, took 17 days through gales and snow squalls, in seas which the navigator,

Frank Worsley, described as a "mountainous westerly swell".

After setting off on 24 April 1916 with just the barest navigational equipment, they reached South Georgia on 10 May 1916. Shackleton, in his later account of the journey, recalled Crean's tuneless singing at the tiller: "He always sang when he was steering, and nobody ever discovered what the song was ... but somehow it was cheerful".

The party made its South Georgia landfall on the uninhabited southern coast, having decided that the risk of aiming directly for the

whaling stations on the north side was too great; if they missed the island to the north they would be swept out into the Atlantic Ocean.

The original plan was to work the

James Caird around the coast, but the boat's rudder had broken off after their initial landing, and some of the party were, in Shackleton's view, unfit for further travel. The three fittest men—Shackleton, Crean, and Worsley—were decided to trek 30 statute miles (48 km) across the island's

glaciated surface, in a hazardous 36-hour journey to the nearest manned whaling station.

This trek was the first recorded crossing of the mountainous island, completed without tents, sleeping bags, or map—their only mountaineering equipment was a carpenter's

adze, a length of alpine rope, and screws from the

James Caird hammered through their boots to serve as

crampons.

They arrived at the whaling station at

Stromness, tired and dirty, hair long and matted, faces blackened by months of cooking by blubber stoves—"the world's dirtiest men", according to Worsley.

They quickly organized a boat to pick up the three on the other side of South Georgia, but thereafter it took Shackleton three months and four attempts by ship to rescue the other 22 men still on Elephant Island.

Later life

After returning to Britain in November 1916, Crean resumed naval duties. On 15 December 1916 he was promoted to the rank of

warrant officer (as a

boatswain), in recognition of his service on the

Endurance,

and was awarded his third

Polar Medal. A month later, in April, he was granted a licence for the sale and consumption of alcohol from his dwelling house, a premises he had purchased in 1916. The business was left in the care of family while he served out his time in the Royal Navy.

On 5 September 1917, Crean married Ellen Herlihy of Annascaul. In early 1920, Shackleton was organising another Antarctic expedition, later to be known as the

Shackleton-Rowett Expedition. He invited Crean to join him, along with other officers from the

Endurance. By this time, however, Crean's second daughter had arrived, and he had plans to open a business following his naval career. He turned down Shackleton's invitation.

On his last naval assignment, with

HMS Hecla, Crean suffered a bad fall which caused lasting effects to his vision. As a result, he was retired on medical grounds on 24 March 1920.

He and Ellen opened a small public house in Annascaul, which he called the

South Pole Inn.

The couple had three daughters, Mary, Kate, and Eileen,

although Kate died when she was four years old.

Throughout his life, Crean remained an extremely modest man. When he returned to Kerry, he put all of his medals away and never again spoke about his experiences in the Antarctic. There is no reliable evidence of Crean giving any interviews to the press.

Smith speculates that this may have been because Kerry was a hotbed of

Irish nationalism and later

Irish republicanism, and, along with County Cork, an epicentre of violence.

The Crean family were once subject to a

Black and Tan raid during the

Irish War of Independence. Their inn was ransacked until the raiders happened across Crean's framed photo in Royal Navy dress uniform and medals. They then left his inn.

On 13 April 1920, Tom Crean was present among crowds gathered in Tralee to protest against the treatment of republican prisoners who had gone on a hunger strike in Mountjoy jail.

Crean's older brother was Cornelius Crean, a sergeant in the

Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC).

Cornelius was based in

County Cork, where he served with the RIC during the

War of Independence.

Sgt. Crean was killed during an

IRA ambush near

Upton on 25 April 1920.

In 1938, Crean became ill with a burst appendix. He was taken to the nearest hospital in

Tralee, but as no surgeon was available, he was transferred to the Bon Secours Hospital in

Cork, where his appendix was removed.

Because the operation had been delayed, an infection developed, and after a week in the hospital he died on 27 July 1938. He was buried in his family's tomb at the cemetery in Ballynacourty, Corkaguiney, County Kerry.

Legacy

- Mount Crean 8,630 feet (2,630 m) in Victoria Land, Antarctica and Mount Crean 2,300 feet (700 m) in Greenland

- Crean Glacier on South Georgia.

- Crean Lake on South Georgia.

- An eight-part 1985 television series, The Last Place on Earth, told the story of Scott's expedition to the South Pole. Hugh Grant and Max von Sydow starred with Irish actor Daragh O'Malley, who portrayed Tom Crean.

- A one-man play, Tom Crean – Antarctic Explorer, has been widely performed since 2001 by author Aidan Dooley, including a special showing at the South Pole Inn, Annascaul, in October 2001. Present were Crean's daughters, Eileen and Mary, both in their 80s. Apparently he never told them stories of his exploits; according to Eileen: "He put his medals and his sword in a box ... and that was that. He was a very humble man".

- In July 2003, a bronze statue of Crean was unveiled across from his pub in Annascaul. It depicts him leaning against a crate whilst holding a pair of hiking poles in one hand and two of his beloved sled dog pups in the other.

- Until its closure in 2017, the Dingle Brewing Company produced 'Tom Crean Lager', named in his honour. In 2016, Crean's granddaughter, Aileen Crean O’Brien, launched 'Expedition Ale' in partnership with Torc Breweries

- In February 2021 it was announced that a new research vessel being commissioned by the Irish government’s Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marinewould be named 'RV Tom Crean', in Crean’s honour.

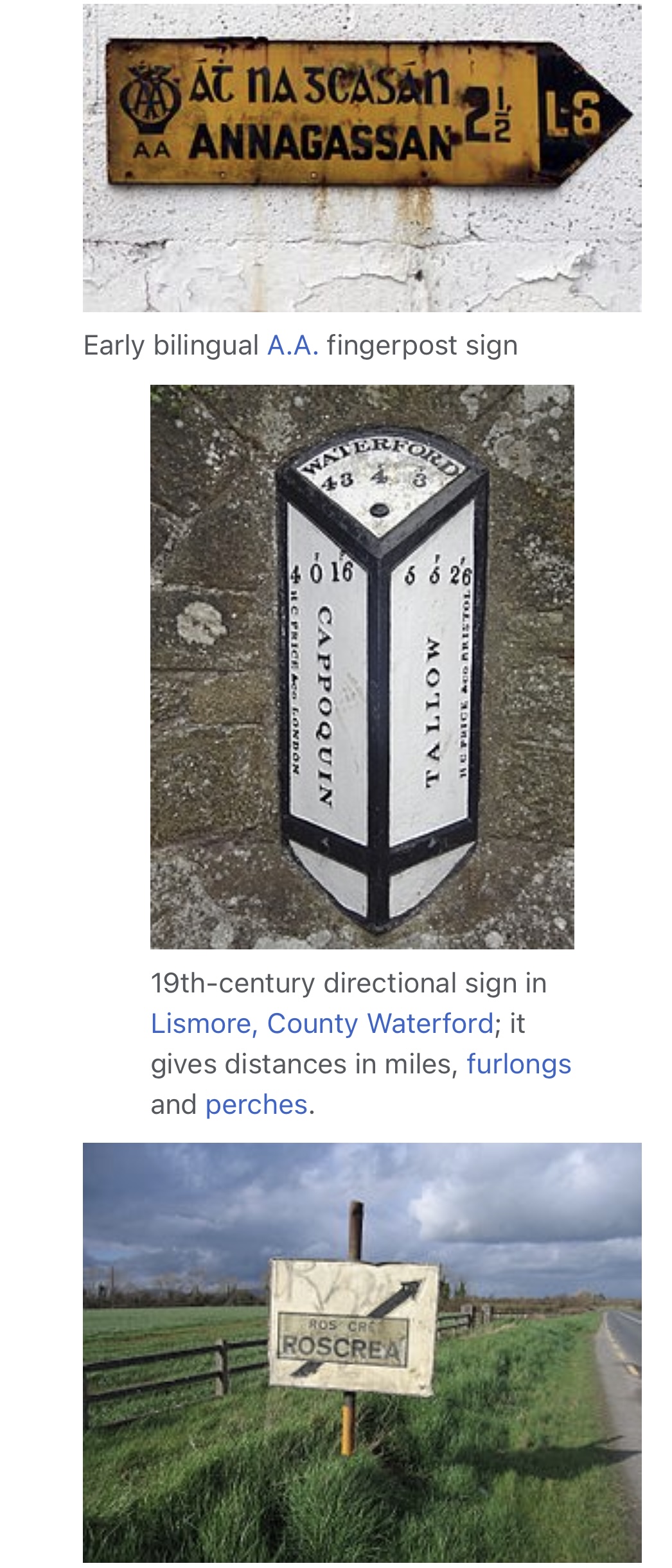

61cm x 69cm

An absolute once off piece of Irish Memorabilia .We at the Irish Pub Emporium were so lucky to acquire from a private collector who has moved overseas.These superb castiron road signs were commissioned by the Irish Free State in the late 1940s post and were initially the responsibility of the newly formed Irish Tourism Organisation -Fógra Failte (later to become Bord Failte and then Failte Ireland).

"The former '

61cm x 69cm

An absolute once off piece of Irish Memorabilia .We at the Irish Pub Emporium were so lucky to acquire from a private collector who has moved overseas.These superb castiron road signs were commissioned by the Irish Free State in the late 1940s post and were initially the responsibility of the newly formed Irish Tourism Organisation -Fógra Failte (later to become Bord Failte and then Failte Ireland).

"The former '