39cm x 44cm. Ballysimon Co Limerick

Ormonde (1883–1904) was an English

Thoroughbred racehorse who won the

English Triple Crown in 1886 and retired undefeated. He also won the

St. James's Palace Stakes,

Champion Stakes and the

Hardwicke Stakes twice. At the time he was often labelled as the 'horse of the century'. Ormonde was trained at

Kingsclere by

John Porter for the

1st Duke of Westminster. His regular jockeys were

Fred Archer and

Tom Cannon. After retiring from racing he suffered fertility problems, but still sired

Orme, who won the

Eclipse Stakes twice.

Background

Ormonde was a bay

colt, bred by

Hugh Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster and foaled in 1883 at Eaton Stud in

Cheshire. Ormonde's sire was

The Derby and

Champion Stakes winner

Bend Or, also bred by the Duke. Bend Or was a successful stallion, his progeny included

Kendal,

Ossory, Orbit, Orion, Orvieto,

Bona Vista and Laveno.

Ormonde's dam was

Doncaster Cup winner

Lily Agnes. She was sired by another Derby winner,

Macaroni. Lily Agnes began to experience problems with her lungs as a four-year-old, to the extent that jockey John Osborne said he could hear her approaching before he saw her. The problem did not interfere with her racing ability as she continued to win at four and five. She then became a top broodmare also foaling

1000 Guineas winner Farewell, Ormonde's full-brother

Ossory and another full-brother Ornament, who produced the outstanding

Sceptre, the only racehorse to win four

British Classic Races outright.

Ormonde was born at half-past six in the evening of 18 March 1883. The Duke's stud-groom Richard Chapman stated that for several months after foaling, Ormonde was

over at the knee. Chapman later said he had never before or since seen a horse with the characteristic so pronounced and that it had seemed impossible for him to ever grow straight. Ormonde did gradually grow out of the problem though and by the time he left the stud to go into training at

Kingsclere, trainer

John Porter told the Duke he was the best yearling the Duke had sent him. However during the winter of 1884/85, Ormonde had trouble with his knees. The treatment he received for this held his training back considerably, with him only having easy cantering exercises until the summer of 1885.

Ormonde grew into a well-built horse standing 16

hands (64 inches, 163 cm) with excellent bone and straight hocks. Porter later said his neck "was the most muscular I ever saw a Thoroughbred possess." He had an excellent shoulder and short powerful hindquarters that led some to call him a racing machine. When galloping, he held his head low and had a notably long stride. He had a kind temperament, healthy appetite and strong constitution. Porter stated the horse was fond of flowers and would even eat the

boutonniere from the jacket of anyone within reach.

Racing career

1885: Two-year-old season

Prior to his racecourse debut, Porter ran Ormonde in a trial against

Kendal, Whipper-in and Whitefriar. Kendal, carrying one pound less, won the trial by a length from Ormonde. Kendal had already had a number of races by this point and Ormonde was nowhere near fully fit. By this point he stood 16 hands high and had a very muscular neck and strong back. Porter also noted that when extended, Ormonde had a very long stride. The Duke rode him in a couple of canters and remarked

"I felt every moment that I was going to be shot over his head, his propelling power is so terrific."

As a two-year-old, Ormonde did not race until October when he won the Post Sweepstakes race at

Newmarket. He started at 5/4 with the filly Modwena, who had won eight races out of ten that year, the 5/6 favourite. In the heavy going, Ormonde went on to win by a length from Modwena. Ormonde's next racecourse appearance came in the Criterion Stakes, again at Newmarket, where his opposition included Oberon and Mephisto. Starting at 4/6, Ormonde won easily by three lengths from Oberon, with Mephisto a distant third.

He then started the

Dewhurst Plate as the 4/11 favourite, ridden by

Fred Archer. After an even start, Ormonde was positioned just behind the leader. As they neared the closing stages, Archer let Ormonde go and he quickly pulled away from the field to beat his stablemate, Whitefriar, easily by four lengths.

The field also included

Miss Jummy, who went on to win the

1000 Guineas and

Epsom Oaks. These three victories earned him £3008. 1885 was considered to have had the best group of two-year-olds for many years.

1886: Three-year-old season

Going into the 1886 season, Ormonde was one of the favourites for the

Derby. He was priced at 11/2, similar to

Minting, Saraband and

The Bard.

2000 Guineas

Ormonde started off his three-year-old campaign in the

2000 Guineas at

Newmarket. The race was considered a clash between Ormonde, the unbeaten

Middle Park winner

Minting and Saraband. In a small field of six, Minting was sent off the 11/10 favourite, Saraband at 3/1 and Ormonde at 7/2. This time Ormonde was ridden by

George Barrett, with Fred Archer riding Saraband. The horses ran almost in line in the early stages. Saraband began to struggle and was beaten with two furlongs to run. At this point Ormonde and Minting took over the lead from St. Mirin. Ormonde then went on to record as easy 2 length victory over Minting, with Mephisto a further 10 lengths back in third, who in turn was two lengths ahead of Saraband.

The Derby

After his Newmarket performance, Ormonde was the favourite for the

Derby with Fred Archer back as his jockey. A small field of 9 went to post, with Ormonde the 40/85 favourite and his main opposition,

The Bard, at 7/2 who. The Bard was also undefeated and had won many races as a two-year-old. The start was not even, with outsider Coracle almost 6 lengths clear of Ormonde, who was a similar distance clear of the rest. Ormonde and The Bard took over the lead at Tattenham corner and the two raced up the straight. The Bard got a neck in front, but when Archer asked Ormonde for an effort, he pulled in front to win by 1½ lengths from The Bard, with St. Mirin a further 10 lengths back in third.

Royal Ascot

At

Royal Ascot against just two opponents, Ormonde lined up as the 3/100 favourite for the

St. James's Palace Stakes. He won easily by ¾ length from Calais. Three days later he faced a stronger field in the

Hardwicke Stakes including 1885

Derby and

St Leger winner

Melton. Ormonde, the 30/100 favourite, won easily again though, beating Melton by 2 lengths. He then had a break from the racecourse.

After Ascot Ormonde was already as short as 1/2 for the St Leger.

Autumn

While Ormonde was galloping one morning shortly before the

St Leger Stakes, Porter noticed him making a whistling noise.

In spite of this infirmity, Ormonde started the final classic of the year as the 1/7 favourite. Ridden again by Archer, he pulled away half a mile out and won easily by 4 lengths from St. Mirin, without even being asked for an effort.

The win made him the fourth winner of the English Triple Crown.

He next ran in the Great Foal Stakes at Newmarket, again winning easily by three lengths from Mephisto.

[13] He then won the Newmarket St Leger in a walkover

and the

Champion Stakes as the 1/100 favourite by a length from Oberon.

Ormonde then entered a free handicap at

Newmarket. Starting the 1/7 favourite and carrying 9 st 2 lb, he won by eight lengths from Mephisto, to whom he was conceding 28 lbs. At the same meeting he won a private sweepstakes in a walkover.

The sweepstakes was an originally scheduled as a match race between Ormonde, The Bard, Melton and possibly Bendigo, the 1886 Eclipse winner. Bendigo was not nominated from the race in the end. The Bard and Melton were though and both forfeited £500 to Ormonde's connections. Throughout the end of the season, Ormonde's breathing had become progressively louder until he was labelled a

roarer.

1887: Four-year-old season

Ormonde did not race until June 1887. His return was assisted by an experimental treatment involving "galvanic shocks" being applied daily to his chest and throat.

His reappearance came at

Royal Ascot in the

Rous Memorial Stakes, where his opposition included Kilwarlin, who went on to win the season's

St. Leger Stakes. Ormonde was conceding 25 pounds to Kilwarin and before the race Kilwarin's owner

Captain Machell said to Porter, "The horse was never foaled that could give Kilwarin 25 pounds and beat him." After

Fred Archer's suicide,

Tom Cannon was now Ormonde's jockey. He led the race throughout and won easily by six lengths from Kilwarlin, with Agave a distant third.

Upon seeing Captain Machell in the paddock after the race Porter said, "Well, what did you think of it now?" Machell replied, "Ormonde is not a horse at all; he's a damned steam-engine."

He raced again the next day in the

Hardwicke Stakes, where he faced a strong field including

Minting and

Eclipse Stakes winner Bendigo. Minting's trainer

Matt Dawson was confident that his horse could win this time due to Ormonde's breathing problems. As the four runners made their way to the starting post he remarked to Porter "You will be beaten today, John. No horse afflicted with Ormonde's infirmity can hope to beat Minting."

Indeed, Porter himself admitted he was not overly confident of victory. During the race

George Barrett, aboard Phil, impeded Ormonde and he was made to struggle for the first time in his career. During the closing stages, Ormonde and Minting battled with each other and Ormonde just came out on top, winning by a

neck, with Bendigo in third.

In his final race, he won the 6 furlong

Imperial Gold Cup at

Newmarket. Starting at 30/100 he made all the running and won by two lengths from Whitefriar.

Ormonde was then retired as the most celebrated horse of his era. He was sent by train to Waterloo Station, then walked to

Grosvenor House in

Mayfair, where he was the guest of honor at a garden party to celebrate

Queen Victoria's

Golden Jubilee.

Race record

Assessment

Ormonde is generally considered one of the greatest racehorses ever. At the time he was often labelled as the 'horse of the century'.

His achievements are even more impressive considering the strength of some of the other horses foaled in 1883. It is said that both

Minting and

The Bard were good enough to have won

The Derby nine out of ten years.

In early 1888 Minting, the horse Ormonde beat easily in the 2000 Guineas, was rated 15 pounds superior to the 1887 Derby winner

Merry Hampton and the 1887

St Leger winner Kilwarlin.

Stud record

Ormonde went to the Duke of Westminster's Eaton Stud in 1888, where he sired seven foals from the sixteen mares he covered, including Goldfinch and

Orme. In 1889, he was moved to Moulton Paddocks in Newmarket, but became sick and could only cover a few mares, with only one live foal produced in 1890. He was subsequently returned to Eaton Stud but his fertility never recovered. To the astonishment of many, Ormonde was then sold overseas. Both he and his dam were roarers, and the Duke felt this could weaken English bloodstock.

Ormonde was sold to Senor Bocau of Argentina for £12,000,

and then in 1893 to William O'Brien Macdonough, of California for £31,250. He stood at the Menlo Stock Farm in California for several years, where he sired 16 foals.

including

Futurity Stakes winner Ormondale.

English foals

c = colt, f = filly

| Foaled |

Name |

Sex |

Notable wins |

Wins |

Prize money |

| 1889 |

Goldfinch |

c |

Biennial Stakes, New Stakes |

2 |

£2,464 |

| 1889 |

Kilkenny |

f |

|

1 |

£164 |

| 1889 |

Llanthony |

c |

Ascot Derby |

4 |

£3,139 |

| 1889 |

Orme |

c |

Middle Park Plate, Dewhurst Plate, Eclipse Stakes (twice), Sussex Stakes, Champion Stakes, Limekiln Stakes, Rous Memorial Stakes, Gordon Stakes |

14 |

£32,528 |

| 1889 |

Orontes II |

f |

|

0 |

|

| 1889 |

Orville |

c |

|

0 |

|

| 1889 |

Sorcerer |

c |

|

1 |

£229 |

| 1890 |

Glenwood |

c |

Aylesford Foal Plate |

2 |

£1,726 |

Despite only siring eight horses in England, Ormonde had a signficant impact at stud. Orme was the

leading sire in Great Britain and Ireland when he sired another Triple Crown winner,

Flying Fox, who went on to be a leading sire in France. Orme also sired

Epsom Derby winner

Orby and

1000 Guineas winner

Witch Elm. Goldfinch sired 1000 Guineas winner Chelandry. After being sold and moving to

California, Goldfinch sired

Preakness Stakes winner

Old England. In America, his son Ormondale went on to sire

Jockey Club Gold Cup winner

Purchase.

Ormonde died in 1904 at age 21 at Rancho Wikiup in

Santa Rosa, California. His disarticulated skeleton/skull were later returned to the

Natural History Museum in

South Kensington,

London.

His male line survives mainly through

Teddy, grandson of Flying Fox. Orby does still have a sire line as well.

Ormonde may have been the model for the fictional horse Silver Blaze in

Arthur Conan Doyle's

Sherlock Holmes short story "

The Adventure of Silver Blaze" (1892).

[23]  The 1938 All-Ireland Football Final Replay on October 23rd, 1938 ended in the most bizarre fashion imaginable when with 2 minutes left to play, Galway supporters, mistakenly believing the referee had blown for full-time, invaded the pitch, causing a 20 minute delay before the final minutes could be played out.

Even more dramatic was the fact that by the time the pitch was cleared, most of the Kerry players seemed to have disappeared.

The 1938 All-Ireland Football Final Replay on October 23rd, 1938 ended in the most bizarre fashion imaginable when with 2 minutes left to play, Galway supporters, mistakenly believing the referee had blown for full-time, invaded the pitch, causing a 20 minute delay before the final minutes could be played out.

Even more dramatic was the fact that by the time the pitch was cleared, most of the Kerry players seemed to have disappeared.

The confusion all began with a free awarded to Kerry by referee Peter Waters of Kildare with Galway leading the defending champions, by 2-4 to 0-6.

The referee placed the ball and blew his whistle for the kick to be taken while running towards the Galway goals. He looked round just as Sean Brosnan was taking the kick and seeing a Galway player too close he blew for the kick to be retaken.

Thinking that he had blown for full-time the jubilant Galway supporters invaded the pitch.

The confusion all began with a free awarded to Kerry by referee Peter Waters of Kildare with Galway leading the defending champions, by 2-4 to 0-6.

The referee placed the ball and blew his whistle for the kick to be taken while running towards the Galway goals. He looked round just as Sean Brosnan was taking the kick and seeing a Galway player too close he blew for the kick to be retaken.

Thinking that he had blown for full-time the jubilant Galway supporters invaded the pitch.

It took all of twenty minutes to clear the pitch but only then did the real problems come to light. Jerry O’Leary Chairman of the Kerry Selection Committee outlined their dilemma.

It took all of twenty minutes to clear the pitch but only then did the real problems come to light. Jerry O’Leary Chairman of the Kerry Selection Committee outlined their dilemma.

Somehow or other Kerry managed to re-field even if the team which played out the remaining minutes bore little resemblance to the starting fifteen.

Somehow or other Kerry managed to re-field even if the team which played out the remaining minutes bore little resemblance to the starting fifteen.

More remarkable again was the fact that Kerry went on to add another point to their total before the referee finally blew for full-time with Galway winners by 2-4 to 0-7.

It was generally agreed that the confusion was of the crowd’s and not the referee’s making but questions remained about the total number of players Kerry had been permitted to use in those final few minutes.

More remarkable again was the fact that Kerry went on to add another point to their total before the referee finally blew for full-time with Galway winners by 2-4 to 0-7.

It was generally agreed that the confusion was of the crowd’s and not the referee’s making but questions remained about the total number of players Kerry had been permitted to use in those final few minutes.

The National and Provincial papers and indeed all available Records to this day list only those 16 Kerry players who were involved prior to the 20 minute interruption but now (80 years on) for the first time all the players who played for Kerry in that October 23rd, 1938 All-Ireland Final Replay can be given their rightful place in the Record Books.

KERRY’s 24:

The National and Provincial papers and indeed all available Records to this day list only those 16 Kerry players who were involved prior to the 20 minute interruption but now (80 years on) for the first time all the players who played for Kerry in that October 23rd, 1938 All-Ireland Final Replay can be given their rightful place in the Record Books.

KERRY’s 24:

That night, in front of a 1,500 crowd, at a Gaelic League organised Siamsa Mór in the Mansion House in Dawson Street, Art McCann presented the Galway team with their winners’ medals.

That night, in front of a 1,500 crowd, at a Gaelic League organised Siamsa Mór in the Mansion House in Dawson Street, Art McCann presented the Galway team with their winners’ medals.

The Kerry players meanwhile joined 300 of their suppoeters at a Ceilidhe hosted by the Kerrymen’s Social Club in Rathmines Town Hall.

The National Newspapers may not always have reported the facts to Galway’s satisfaction but there can be no questioning the support of Galway County Council.

The Kerry players meanwhile joined 300 of their suppoeters at a Ceilidhe hosted by the Kerrymen’s Social Club in Rathmines Town Hall.

The National Newspapers may not always have reported the facts to Galway’s satisfaction but there can be no questioning the support of Galway County Council.

Needless to say the Galway players received an unprecedented welcome on their return to Galway having first been feted along the way in Mullingar, Streamstown, Moate and Athlone.

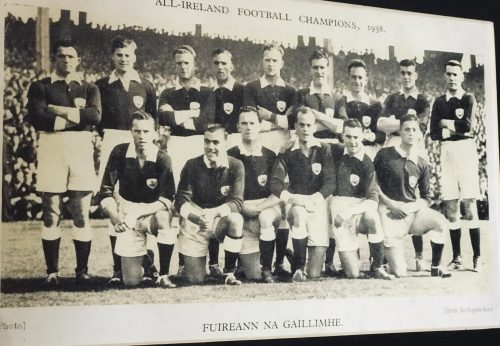

GALWAY – 1938 ALL-IRELAND SENIOR FOOTBALL CHAMPIONS

Needless to say the Galway players received an unprecedented welcome on their return to Galway having first been feted along the way in Mullingar, Streamstown, Moate and Athlone.

GALWAY – 1938 ALL-IRELAND SENIOR FOOTBALL CHAMPIONS

Back (L-R) Bobby Beggs, Ralph Griffin, John Burke, Jimmy McGauran, Charlie Connolly, Brendan Nestor, Dinny Sullivan, Mick Connaire, Martin Kelly. Front (L-R) Frank Cunniffe, Jackie Flavin, Mick Higgins, John ‘Tull’ Dunne (Capt), Ned Mulholland, Mick Raftery.

Substitutes: (not in photograph) Mick Ryder and Pat McDonagh.

TIME ADDED ON:

Not far behind the controversy surrounding the last few minutes of 1938 All-Ireland Football Final Replay was the controversy surrounding the last few seconds of the drawn match played a month earlier.

Back (L-R) Bobby Beggs, Ralph Griffin, John Burke, Jimmy McGauran, Charlie Connolly, Brendan Nestor, Dinny Sullivan, Mick Connaire, Martin Kelly. Front (L-R) Frank Cunniffe, Jackie Flavin, Mick Higgins, John ‘Tull’ Dunne (Capt), Ned Mulholland, Mick Raftery.

Substitutes: (not in photograph) Mick Ryder and Pat McDonagh.

TIME ADDED ON:

Not far behind the controversy surrounding the last few minutes of 1938 All-Ireland Football Final Replay was the controversy surrounding the last few seconds of the drawn match played a month earlier.

The sides were level, Kerry 2-06 Galway 3-03, when Kerry’s J.J. Landers sent the ball between the Galway uprights for what looked like the winning point. However the thousands of celebrating Kerry supporters making for the Croke Park exits were soon stopped in their tracks.

The sides were level, Kerry 2-06 Galway 3-03, when Kerry’s J.J. Landers sent the ball between the Galway uprights for what looked like the winning point. However the thousands of celebrating Kerry supporters making for the Croke Park exits were soon stopped in their tracks.

It was cruel luck on Kerry and while there were many who criticised the referee, Tom Culhane from Glin, County Limerick, for blowing the final whistle while John Joe Landers was it the act of shooting, Kerry’s County Board Chairman Denis J. Bailey wasn’t among them.

At the next Central Council meeting, in a remarkably generous response to the Referee’s Report being read he stated that ‘they in Kerry were quite satisfied with the result’ and ‘They wished to pay a tribute to Galway for their sporting spirit and also to the referee who, in their opinion, carried out his duties very well.’

The Central Council then awarded the two counties £300 each towards the costs of the two-week Collective Training Camps both counties had planned in the lead up to the Replay on October 23rd. Munster Council granted Kerry (pictured here in Collective Training) an additional £100.

It was cruel luck on Kerry and while there were many who criticised the referee, Tom Culhane from Glin, County Limerick, for blowing the final whistle while John Joe Landers was it the act of shooting, Kerry’s County Board Chairman Denis J. Bailey wasn’t among them.

At the next Central Council meeting, in a remarkably generous response to the Referee’s Report being read he stated that ‘they in Kerry were quite satisfied with the result’ and ‘They wished to pay a tribute to Galway for their sporting spirit and also to the referee who, in their opinion, carried out his duties very well.’

The Central Council then awarded the two counties £300 each towards the costs of the two-week Collective Training Camps both counties had planned in the lead up to the Replay on October 23rd. Munster Council granted Kerry (pictured here in Collective Training) an additional £100.

Prior to that Central Council meeting, General Secretary, Pádraig Ó’Caoimh, received a telephone call from the New York GAA suggesting the replay take place in New York but the request (which was successfully repeated nine years later in 1947) was on this occasion turned down.

However doubts about the Replay even going ahead were immediately raised.

Prior to that Central Council meeting, General Secretary, Pádraig Ó’Caoimh, received a telephone call from the New York GAA suggesting the replay take place in New York but the request (which was successfully repeated nine years later in 1947) was on this occasion turned down.

However doubts about the Replay even going ahead were immediately raised.

Satisfactory transport arrangements were eventually agreed and the match went ahead although the Kerry supporters who left Tralee on the so-called ‘ghost’ train at 1am on the morning of the October 23rd may still have felt hard done by.

Satisfactory transport arrangements were eventually agreed and the match went ahead although the Kerry supporters who left Tralee on the so-called ‘ghost’ train at 1am on the morning of the October 23rd may still have felt hard done by.

In the lead-up to the game the Galway selectors expressed their delight at the success of their forwards short hand-passing game against the Kerry backs in the drawn match although there were some worries that not all their players had been able to attend the first week of Collective Training and of course there was Kerry’s Replay record to be considered.

Kerry had previously played in 4 All-Ireland Replays and won them all, a great source of encouragement to the Kerry supporters.

However amid some reports of disharmony within the Kerry camp, following a ‘trial match’ on the Sunday before the Replay, the Kerry selection Committee dropped a real bombshell.

Joe Keohane (Dublin Geraldines) who had been Kerry’s regular full-back for the previous two years and was one of the stars of their 1937 All-Ireland win over Cavan was replaced by young Paddy ‘Bawn’ Brosnan a member of the 1938 Kerry Junior team.

A back injury to Kerry’s best forward, J.J. Landers made him an extreme doubt for the Replay with Martin Regan on stand-by to take his place if required which is exactly what happened before that fateful free-kick, that infamous 20 minute delay and Kerry’s unprecedented use of 24 players.

Most definitely an All-Ireland Final and Final Replay never to be forgotten.

In the lead-up to the game the Galway selectors expressed their delight at the success of their forwards short hand-passing game against the Kerry backs in the drawn match although there were some worries that not all their players had been able to attend the first week of Collective Training and of course there was Kerry’s Replay record to be considered.

Kerry had previously played in 4 All-Ireland Replays and won them all, a great source of encouragement to the Kerry supporters.

However amid some reports of disharmony within the Kerry camp, following a ‘trial match’ on the Sunday before the Replay, the Kerry selection Committee dropped a real bombshell.

Joe Keohane (Dublin Geraldines) who had been Kerry’s regular full-back for the previous two years and was one of the stars of their 1937 All-Ireland win over Cavan was replaced by young Paddy ‘Bawn’ Brosnan a member of the 1938 Kerry Junior team.

A back injury to Kerry’s best forward, J.J. Landers made him an extreme doubt for the Replay with Martin Regan on stand-by to take his place if required which is exactly what happened before that fateful free-kick, that infamous 20 minute delay and Kerry’s unprecedented use of 24 players.

Most definitely an All-Ireland Final and Final Replay never to be forgotten.

The Galway and Kerry players parade in front of the newly opened (1938) Cusack Stand

The Galway and Kerry players parade in front of the newly opened (1938) Cusack Stand

This historic brand of whiskey has now been revived by the

This historic brand of whiskey has now been revived by the

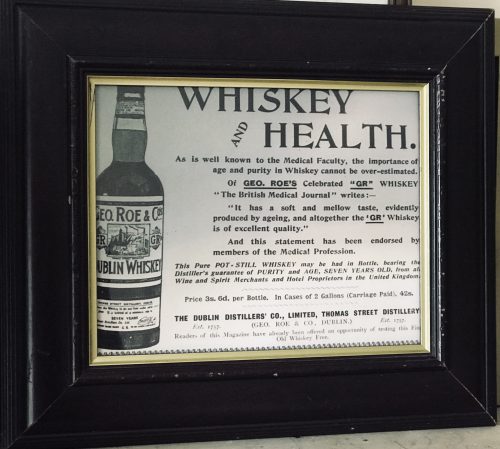

By 1832, George Roe had inherited both of these plants which were near to each other. George continued their expansion and leased additional premises in Mount Brown, which were used as maltings, kilns, and warehouses.By 1827, output of the Thomas Street Distillery was reported as being 244,279 gallons. George Roe’s two sons, Henry and George, succeeded to the ownership in 1862, by which point the firm was large and prosperous, and the Roes a family of wealth and influence. So much so that in 1878, the Roes could afford to donate £250,000, a very large sum in those days, to the restoration of

By 1832, George Roe had inherited both of these plants which were near to each other. George continued their expansion and leased additional premises in Mount Brown, which were used as maltings, kilns, and warehouses.By 1827, output of the Thomas Street Distillery was reported as being 244,279 gallons. George Roe’s two sons, Henry and George, succeeded to the ownership in 1862, by which point the firm was large and prosperous, and the Roes a family of wealth and influence. So much so that in 1878, the Roes could afford to donate £250,000, a very large sum in those days, to the restoration of

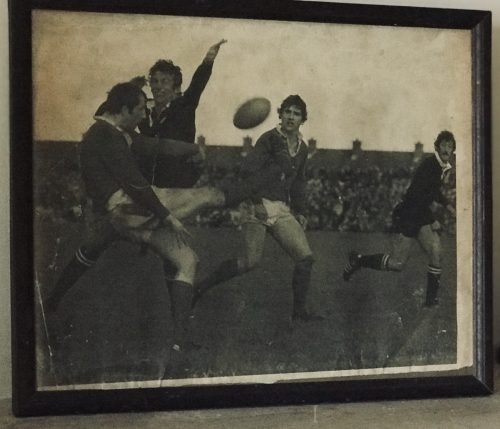

Many years on, Stuart Wilson vividly recalled the Dennison tackles and spoke about them in remarkable detail and with commendable honesty: “The move involved me coming in from the blind side wing and it had been working very well on tour. It was a workable move and it was paying off so we just kept rolling it out. Against Munster, the gap opened up brilliantly as it was supposed to except that there was this little guy called Seamus Dennison sitting there in front of me.

“He just basically smacked the living daylights out of me. I dusted myself off and thought, I don’t want to have to do that again. Ten minutes later, we called the same move again thinking we’d change it slightly but, no, it didn’t work and I got hammered again.”

The game was 11 minutes old when the most famous try in the history of Munster rugby was scored.

Tom Kiernan recalled: “It came from a great piece of anticipation by Bowen who in the first place had to run around his man to get to Ward’s kick ahead. He then beat two men and when finally tackled, managed to keep his balance and deliver the ball to Cantillon who went on to score. All of this was evidence of sharpness on Bowen’s part.”

Very soon it would be 9-0. In the first five minutes, a towering garryowen by skipper Canniffe had exposed the vulnerability of the New Zealand rearguard under the high ball. They were to be examined once or twice more but it was from a long range but badly struck penalty attempt by Ward that full-back Brian McKechnie knocked on some 15 yards from his line and close to where Cantillon had touched down a few minutes earlier. You could sense White, Whelan, McLoughlin and co in the front five of the Munster scrum smacking their lips as they settled for the scrum. A quick, straight put-in by Canniffe, a well controlled heel, a smart pass by the scrum-half to Ward and the inevitability of a drop goal. And that’s exactly what happened.

The All Blacks enjoyed the majority of forward possession but the harder they tried, the more they fell into the trap set by the wily Kiernan and so brilliantly carried out by every member of the Munster team.

The tourists might have edged the line-out contest through Andy Haden and Frank Oliver but scrum-half Mark Donaldson endured a miserable afternoon as the Munster forwards poured through and buried him in the Thomond Park turf.

As the minutes passed and the All Blacks became more and more unsure as to what to try next, the Thomond Park hordes chanted “Munster-Munster–Munster” to an ever increasing crescendo until with 12 minutes to go, the noise levels reached deafening proportions.

And then ... a deep, probing kick by Ward put Wilson under further pressure. Eventually, he stumbled over the ball as it crossed the line and nervously conceded a five-metre scrum. The Munster heel was disrupted but the ruck was won, Tucker gained possession and slipped a lovely little pass to Ward whose gifted feet and speed of thought enabled him in a twinkle to drop a goal although surrounded by a swarm of black jerseys. So the game entered its final 10 minutes with the All Blacks needing three scores to win and, of course, that was never going to happen.

Munster knew this, so, too, did the All Blacks. Stu Wilson admitted as much as he explained his part in Wardy’s second drop goal: “Tony Ward banged it down, it bounced a little bit, jigged here, jigged there, and I stumbled, fell over, and all of a sudden the heat was on me. They were good chasers. A kick is a kick — but if you have lots of good chasers on it, they make bad kicks look good. I looked up and realised — I’m not going to run out of here so I just dotted it down. I wasn’t going to run that ball back out at them because five of those mad guys were coming down the track at me and I’m thinking, I’m being hit by these guys all day and I’m looking after my body, thank you. Of course it was a five-yard scrum and Ward banged over another drop goal. That was it, there was the game”.

The final whistle duly sounded with Munster 12 points ahead but the heroes of the hour still had to get off the field and reach the safety of the dressing room. Bodies were embraced, faces were kissed, backs were pummelled, you name it, the gauntlet had to be walked. Even the All Blacks seemed impressed with the sense of joy being released all about them. Andy Haden recalled “the sea of red supporters all over the pitch after the game, you could hardly get off for the wave of celebration that was going on. The whole of Thomond Park glowed in the warmth that someone had put one over on the Blacks.”

Controversially, the All Blacks coach, Jack Gleeson (usually a man capable of accepting the good with the bad and who passed away of cancer within 12 months of the tour), in an unguarded (although possibly misunderstood) moment on the following day, let slip his innermost thoughts on the game.

“We were up against a team of kamikaze tacklers,” he lamented. “We set out on this tour to play 15-man rugby but if teams were to adopt the Munster approach and do all they could to stop the All Blacks from playing an attacking game, then the tour and the game would suffer.”

It was interpreted by the majority of observers as a rare piece of sour grapes from a group who had accepted the defeat in good spirit and it certainly did nothing to diminish Munster respect for the All Blacks and their proud rugby tradition.

Many years on, Stuart Wilson vividly recalled the Dennison tackles and spoke about them in remarkable detail and with commendable honesty: “The move involved me coming in from the blind side wing and it had been working very well on tour. It was a workable move and it was paying off so we just kept rolling it out. Against Munster, the gap opened up brilliantly as it was supposed to except that there was this little guy called Seamus Dennison sitting there in front of me.

“He just basically smacked the living daylights out of me. I dusted myself off and thought, I don’t want to have to do that again. Ten minutes later, we called the same move again thinking we’d change it slightly but, no, it didn’t work and I got hammered again.”

The game was 11 minutes old when the most famous try in the history of Munster rugby was scored.

Tom Kiernan recalled: “It came from a great piece of anticipation by Bowen who in the first place had to run around his man to get to Ward’s kick ahead. He then beat two men and when finally tackled, managed to keep his balance and deliver the ball to Cantillon who went on to score. All of this was evidence of sharpness on Bowen’s part.”

Very soon it would be 9-0. In the first five minutes, a towering garryowen by skipper Canniffe had exposed the vulnerability of the New Zealand rearguard under the high ball. They were to be examined once or twice more but it was from a long range but badly struck penalty attempt by Ward that full-back Brian McKechnie knocked on some 15 yards from his line and close to where Cantillon had touched down a few minutes earlier. You could sense White, Whelan, McLoughlin and co in the front five of the Munster scrum smacking their lips as they settled for the scrum. A quick, straight put-in by Canniffe, a well controlled heel, a smart pass by the scrum-half to Ward and the inevitability of a drop goal. And that’s exactly what happened.

The All Blacks enjoyed the majority of forward possession but the harder they tried, the more they fell into the trap set by the wily Kiernan and so brilliantly carried out by every member of the Munster team.

The tourists might have edged the line-out contest through Andy Haden and Frank Oliver but scrum-half Mark Donaldson endured a miserable afternoon as the Munster forwards poured through and buried him in the Thomond Park turf.

As the minutes passed and the All Blacks became more and more unsure as to what to try next, the Thomond Park hordes chanted “Munster-Munster–Munster” to an ever increasing crescendo until with 12 minutes to go, the noise levels reached deafening proportions.

And then ... a deep, probing kick by Ward put Wilson under further pressure. Eventually, he stumbled over the ball as it crossed the line and nervously conceded a five-metre scrum. The Munster heel was disrupted but the ruck was won, Tucker gained possession and slipped a lovely little pass to Ward whose gifted feet and speed of thought enabled him in a twinkle to drop a goal although surrounded by a swarm of black jerseys. So the game entered its final 10 minutes with the All Blacks needing three scores to win and, of course, that was never going to happen.

Munster knew this, so, too, did the All Blacks. Stu Wilson admitted as much as he explained his part in Wardy’s second drop goal: “Tony Ward banged it down, it bounced a little bit, jigged here, jigged there, and I stumbled, fell over, and all of a sudden the heat was on me. They were good chasers. A kick is a kick — but if you have lots of good chasers on it, they make bad kicks look good. I looked up and realised — I’m not going to run out of here so I just dotted it down. I wasn’t going to run that ball back out at them because five of those mad guys were coming down the track at me and I’m thinking, I’m being hit by these guys all day and I’m looking after my body, thank you. Of course it was a five-yard scrum and Ward banged over another drop goal. That was it, there was the game”.

The final whistle duly sounded with Munster 12 points ahead but the heroes of the hour still had to get off the field and reach the safety of the dressing room. Bodies were embraced, faces were kissed, backs were pummelled, you name it, the gauntlet had to be walked. Even the All Blacks seemed impressed with the sense of joy being released all about them. Andy Haden recalled “the sea of red supporters all over the pitch after the game, you could hardly get off for the wave of celebration that was going on. The whole of Thomond Park glowed in the warmth that someone had put one over on the Blacks.”

Controversially, the All Blacks coach, Jack Gleeson (usually a man capable of accepting the good with the bad and who passed away of cancer within 12 months of the tour), in an unguarded (although possibly misunderstood) moment on the following day, let slip his innermost thoughts on the game.

“We were up against a team of kamikaze tacklers,” he lamented. “We set out on this tour to play 15-man rugby but if teams were to adopt the Munster approach and do all they could to stop the All Blacks from playing an attacking game, then the tour and the game would suffer.”

It was interpreted by the majority of observers as a rare piece of sour grapes from a group who had accepted the defeat in good spirit and it certainly did nothing to diminish Munster respect for the All Blacks and their proud rugby tradition.

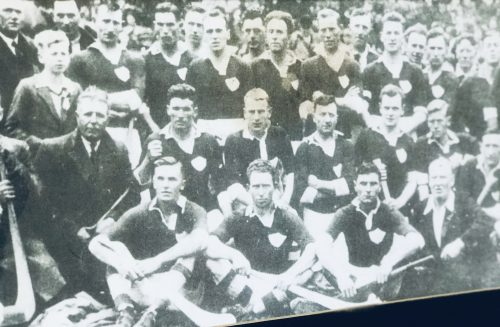

Tom Moloughney, Jimmy Doyle, and Kieran Carey relax in the dressing room after Tipperary’s victory over Dublin in the 1961 All-Ireland final, a success that was to be repeated the following year. Picture from ‘The GAA — A People’s History’

Tom Moloughney, Jimmy Doyle, and Kieran Carey relax in the dressing room after Tipperary’s victory over Dublin in the 1961 All-Ireland final, a success that was to be repeated the following year. Picture from ‘The GAA — A People’s History’

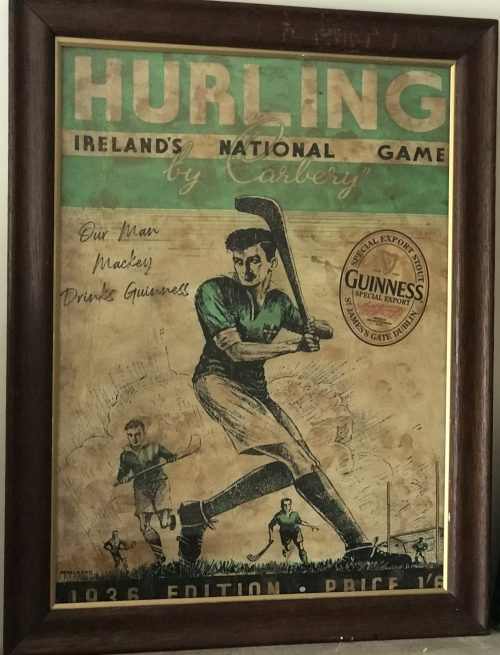

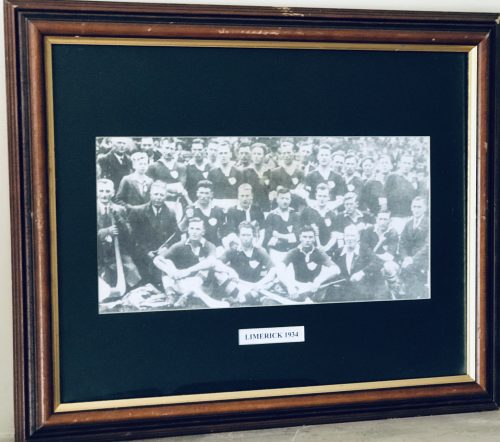

Limerick 5-2 Dublin 2-6

D Clohessy 4-0, M Mackey 1-1, J O’Connell 0-1

Limerick 5-2 Dublin 2-6

D Clohessy 4-0, M Mackey 1-1, J O’Connell 0-1