-

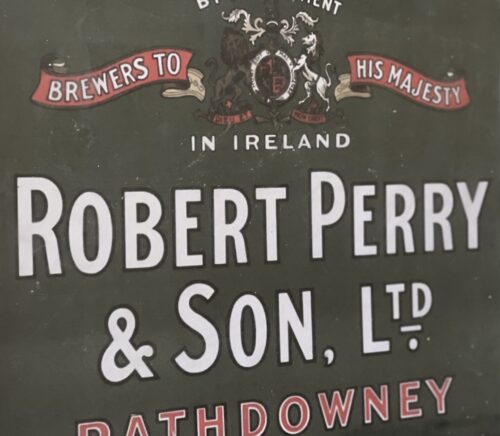

40cm x 34cm Limerickessrs Robert Perry & Son Limited were registered as a limited company in 1877, but the brewery dates back to 1800 when it was started by the Perry family. The brewery was located in Rathdowney, county Laois. In connection with the Brewery were extensive maltings, with branches at Donaghmore, Brosna and Roscrea, and only Irish barley was used. It is claimed that they were the first brewer to chill and filter ale in around 1900. A unique feature of the business is the brewing of non-deposit ale under sole rights for Ireland and the company has the distinction of holding a Royal warrant as brewers to Queen Victoria. From 1950 their trade deteriorated and losses were incurred. The Dixon family (Green's of Luton and subsequently Flowers) had a controlling interest. In 1956 Captain T.R. Dixon acquired the entire share capital of the company. In the same year, they were receiving assistance from Flowers in the form of a second hand plant to produce chilled and filtered beers. In June 1957 Cherry's Breweries Limited bought out a quantity of ordinary and preference stock. In August 1959 Cherry's made a successful offer for the outstanding stock, and Perry's became a wholly owned subsidiary of Cherry's Breweries Limited. In 1965 they were owned by Cherry's Breweries Limited (held by AGS(D) and IAB). The directors were D.O. Williams (Assistant Managing Director of AGS(D)), A.C. Parker and J.D. Hudson. The secretary was N.J. McCullough (he also held the position of accountant), the brewer W.St.J. Mitchell. They employed 5 male office staff, 37 male employees in the brewery and maltings and 8 drivers. The products included: Perry's India Pale Ale, Perry's Pale Ale, Perry's XX Ale, Perry's X Ale. There were no trademarks held.

40cm x 34cm Limerickessrs Robert Perry & Son Limited were registered as a limited company in 1877, but the brewery dates back to 1800 when it was started by the Perry family. The brewery was located in Rathdowney, county Laois. In connection with the Brewery were extensive maltings, with branches at Donaghmore, Brosna and Roscrea, and only Irish barley was used. It is claimed that they were the first brewer to chill and filter ale in around 1900. A unique feature of the business is the brewing of non-deposit ale under sole rights for Ireland and the company has the distinction of holding a Royal warrant as brewers to Queen Victoria. From 1950 their trade deteriorated and losses were incurred. The Dixon family (Green's of Luton and subsequently Flowers) had a controlling interest. In 1956 Captain T.R. Dixon acquired the entire share capital of the company. In the same year, they were receiving assistance from Flowers in the form of a second hand plant to produce chilled and filtered beers. In June 1957 Cherry's Breweries Limited bought out a quantity of ordinary and preference stock. In August 1959 Cherry's made a successful offer for the outstanding stock, and Perry's became a wholly owned subsidiary of Cherry's Breweries Limited. In 1965 they were owned by Cherry's Breweries Limited (held by AGS(D) and IAB). The directors were D.O. Williams (Assistant Managing Director of AGS(D)), A.C. Parker and J.D. Hudson. The secretary was N.J. McCullough (he also held the position of accountant), the brewer W.St.J. Mitchell. They employed 5 male office staff, 37 male employees in the brewery and maltings and 8 drivers. The products included: Perry's India Pale Ale, Perry's Pale Ale, Perry's XX Ale, Perry's X Ale. There were no trademarks held. -

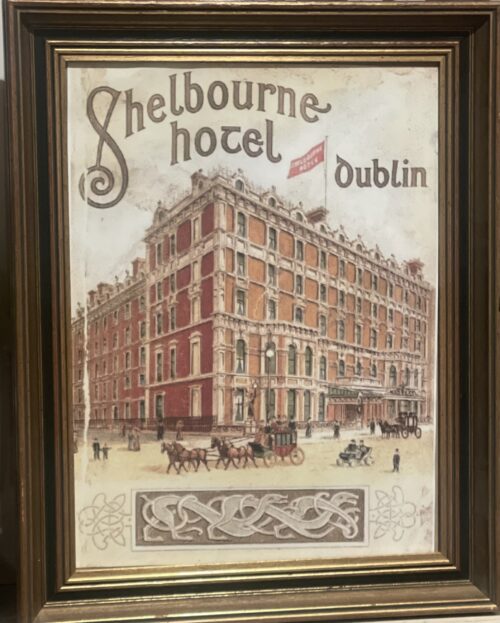

48cm x 38cm The Shelbourne Hotel is a historic hotel in Dublin, Ireland, situated in a landmark building on the north side of St Stephen's Green. Currently owned by Kennedy Wilsonand operated by Marriott International, the hotel has 265 rooms in total and reopened in March 2007 after undergoing an eighteen-month refurbishment.

48cm x 38cm The Shelbourne Hotel is a historic hotel in Dublin, Ireland, situated in a landmark building on the north side of St Stephen's Green. Currently owned by Kennedy Wilsonand operated by Marriott International, the hotel has 265 rooms in total and reopened in March 2007 after undergoing an eighteen-month refurbishment.History

The Shelbourne Hotel was founded in 1824 by Martin Burke, a native of Tipperary, when he acquired three adjoining townhousesoverlooking Stephen's Green, Europe's largest garden square. Burke named his grand new hotel The Shelbourne, after William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne. William Makepeace Thackeray was an early guest, staying in 1842 and including a piece about the Shelbourne in The Irish Sketch-Book (1843). In the early 1900s, Alois Hitler jr., the elder half-brother of Adolf Hitler, worked in the hotel while in Dublin. During the 1916 Easter Rising the hotel was occupied by 40 British troops under Captain Andrews to counter the Irish Citizen Armyand Irish Volunteer forces, commanded by Michael Mallin, who had occupied Stephen's Green. In 1922, the Constitution of the Irish Free State was drafted in room 112, now known as The Constitution Room. The facade was refurbished in 2016, winning an award from the Irish Georgian Society. In December 2018 UEFA's executive committee made the draw for the 2019 UEFA Nations League Finals in the hotel.Statues

A major redesign by John McCurdy was completed in 1867, with the Foundry of Val d'Osne casting the four external caryatid style torchère statues. These were based on two repeated beaux-arts neoclassical models originally sculpted by the prolific French sculptor Mathurin Moreau entitled Égyptienne – the two female Ancient Egyptianfigures flanking either side of the front door, and Négresse – the two female ancient Kushite (Nubian)figures flanking either corner of the main building. All four statues are wearing gold coloured anklets, and are draped, with jewellery picked out in gilt while supporting a torch with a frosted glass flambeau shade.All four statues are on a circular base with a further square metal plinth with cartouches to the angles indicating royal descent. In feint writing at the front of the circular base of all four statues can be seen the name of the foundry which produced the statues Val d'Osne. Of the several other examples of the castings, the most notable can be seen in the porch of the hôtel de ville (town hall) in the French town of Remiremont as well as outside the mausoleum of the architect Temple Hoyne Buellin Denver, Colorado and in the Jardins do Palácio de Cristal in Porto.In all three cases the door is flanked either side by one Égyptienne and one Négresse statue indicating parity. In July 2020, the statues at the front of the building were removed by management as a precautionary response to the toppling and removal of statues following the murder of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter protests. This move resulted from the belief that either two or all four of the statues represented Nubian slaves shown in manacles. Both histories of the hotel, that of 1951 by Elizabeth Bowen and that of 1999 by Michael O'Sullivan, state that two of the statues represent slaves or servants, with Bowen stating "on each stands a female statue, Nubian in aspect, holding a torch shaped lamp". Kyle Leyden, an art historian at the Courtauld Institute, argued that none of the statues are of the established "Nubian slave" type, and that all four figures wear ankletsindicating aristocratic status, rather than shackles.After an examination by Paula Murphy, an art historian at University College Dublin, concluded that the statues were not representations of slaves, it was announced that they would be restored to their plinths.After being cleaned, they were reinstalled on the night of 14 December. In James Joyce's Ulysses, Leopold Bloom remembers the Shelbourne as where "Mrs Miriam Dandrade", a "Divorced Spanish American" sold him "her old wraps and black underclothes -

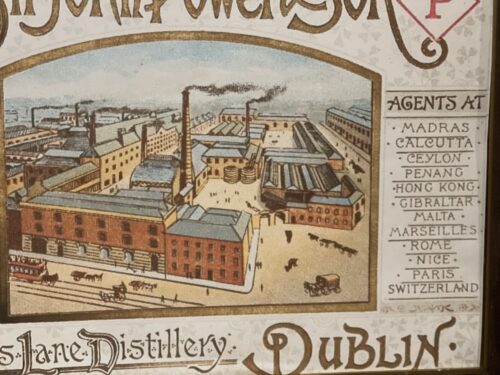

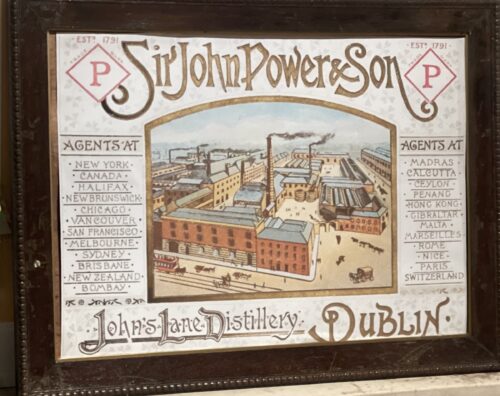

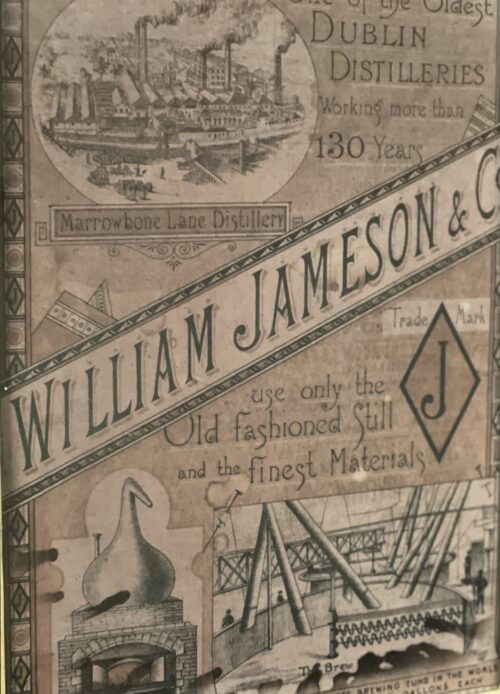

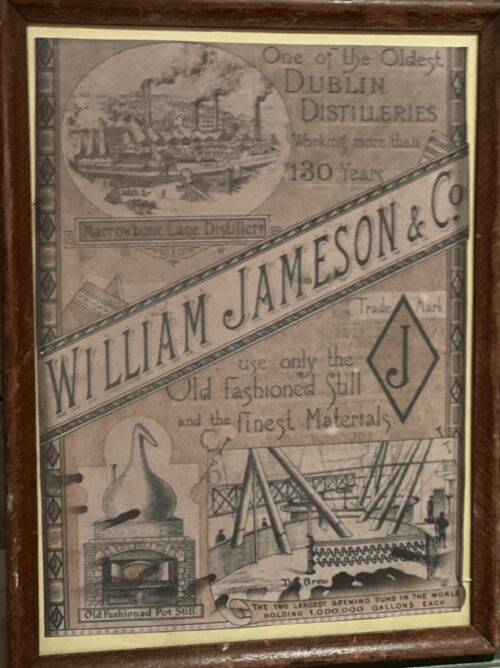

68cm x 51cm In 1791 James Power, an innkeeper from Dublin, established a small distillery at his public house at 109 Thomas St., Dublin. The distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son, and had moved to a new premises at John's Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O'Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the "Big Four") came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John's Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as "about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere". At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:"The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels." The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power's Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John's Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John's Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John's Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery's pot stills were saved and now located in the college's Red Square. Origins : Dublin City Dimensions : 100cm x 70cm 20kg (specially constructed damage proof shipping container)

68cm x 51cm In 1791 James Power, an innkeeper from Dublin, established a small distillery at his public house at 109 Thomas St., Dublin. The distillery, which had an output of about 6,000 gallons in its first year of operation, initially traded as James Power and Son, but by 1822 had become John Power & Son, and had moved to a new premises at John's Lane, a side street off Thomas Street. At the time the distillery had three pot stills, though only one, a 500-gallon still is thought to have been in use. Following reform of the distilling laws in 1823, the distillery expanded rapidly. In 1827, production was reported at 160,270 gallons,and by 1833 had grown to 300,000 gallons per annum. As the distillery grew, so too did the stature of the family. In 1841, John Power, grandson of the founder was awarded a baronet, a hereditary title. In 1855, his son Sir James Power, laid the foundation stone for the O'Connell Monument, and in 1859 became High Sheriff of Dublin. In 1871, the distillery was expanded and rebuilt in the Victorian style, becoming one of the most impressive sights in Dublin.After expansion, output at the distillery rose to 700,000 gallons per annum, and by the 1880s, had reached about 900,000 gallons per annum, at which point the distillery covered over six acres of central Dublin, and had a staff of about 300 people.During this period, when the Dublin whiskey distilleries were amongst the largest in the world, the family run firms of John Powers, along with John Jameson, William Jameson, and George Roe, (collectively known as the "Big Four") came to dominate the Irish distilling landscape, introducing several innovations. In 1886, John Power & Son began bottling their own whiskey, rather than following the practice customary at the time, of selling whiskey directly to merchants and bonders who would bottle it themselves. They were the first Dublin distillery to do so, and one of the first in the world.A gold label adorned each bottle and it was from these that the whiskey got the name Powers Gold Label. When Alfred Barnard, the British historian visited John's Lane in the late 1880s, he noted the elegance and cleanliness of the buildings, and the modernity of the distillery, describing it as "about as complete a work as it is possible to find anywhere". At the time of his visit, the distillery was home to five pot stills, two of which with capacities of 25,000 gallons, were amongst the largest ever built.In addition, Barnard was high in his praise for Powers whiskey, noting:"The old make, which we drank with our luncheon was delicious and finer than anything we had hitherto tasted.It was as perfect in flavour, and as pronounced in the ancient aroma of Irish Whiskey so dear to to the hearts of connoisseurs,as one could possibly desire and we found a small flask of it very useful afterwards on our travels." The last member of the family to sit on the board was Sir Thomas Talbot Power,who died in 1930,and with him the Power's Baronetcy. However, ownership remained in the family until 1966, and several descendants of his sisters remained at work with the company until recent times. In 1961, a Coffey still was installed in John's Lane Distillery, allowing the production of vodka and gin, in addition to the testing of grain whiskey for use in blended whiskey. This was a notable departure for the firm, as for many years the big Dublin distilling dynasties had shunned the use of Coffey stills, questioning if their output, grain whiskey could even be termed whiskey. However, with many of the Irish distilleries having closed in the early 20th century in part due to their failure to embrace a change in consumer preference towards blended whiskey, Powers were instrumental in convincing the remaining Irish distilleries to reconsider their stance on blended whiskey. In 1966, with the Irish whiskey industry still struggling following Prohibition in the United States, the Anglo-Irish Trade War and the rise of competition from Scotch whiskey, John Powers & Son joined forces with the only other remaining distillers in the Irish Republic, the Cork Distilleries Company and their Dublin rivals John Jameson & Son, to form Irish Distillers. Soon after, in a bold move, Irish Distillers decided to close all of their existing distilleries, and to consolidate production at a new purpose-built facility in Midleton (the New Midleton Distillery) alongside their existing Old Midleton Distillery. The new distillery opened in 1975, and a year later, production ceased at John's Lane Distillery and began anew in Cork, with Powers Gold Label and many other Irish whiskeys reformulated from single pot stills whiskeys to blends. In 1989, Irish Distillers itself became a subsidiary of Pernod-Ricard following a friendly takeover.Since the closure of the John's Lane distillery, many of the distillery buildings were demolished. However, some of the buildings have been incorporated into the National College of Art and Design, and are now protected structures. In addition, three of the distillery's pot stills were saved and now located in the college's Red Square. Origins : Dublin City Dimensions : 100cm x 70cm 20kg (specially constructed damage proof shipping container) The Still House at John's Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

The Still House at John's Lane Distillery, as it looked when Alfred Barnard visited in the 1800s.

-

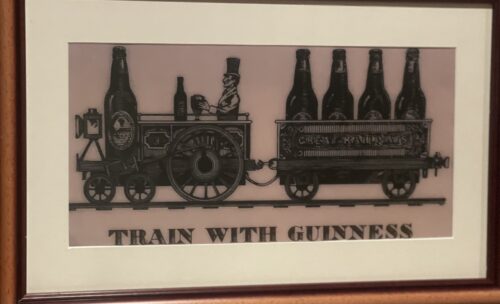

Vintage type come in for a Guinness advert with suitably distressed appearance. Dimensions : 23cm x 40cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm

Vintage type come in for a Guinness advert with suitably distressed appearance. Dimensions : 23cm x 40cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm -

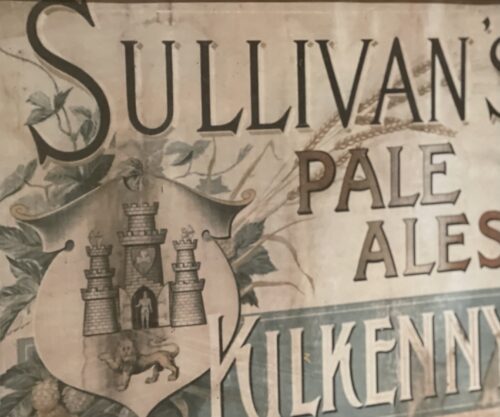

37cm x 47cm Limerick Sullivan’s Brewing Company opened for business over three hundred years ago in The Maltings on James’s Street, smack bang in the middle of Kilkenny City.

37cm x 47cm Limerick Sullivan’s Brewing Company opened for business over three hundred years ago in The Maltings on James’s Street, smack bang in the middle of Kilkenny City.Up until the early 1700s, brewing on a large scale was a rarity, this resulted in many small breweries springing up all around the country, with little or no consistency in the beer that was being produced. Back then, to guarantee that each pint was as good as the last, required brewing on a bigger, more exacting scale.

Enter Mr. Sullivan, a man of high morals, integrity and a good nose for great beer. Through his belief and hard work he established a brewery the likes of which had never been seen in Kilkenny. He only used the very best local ingredients and the very best brewing methods to ensure that every barrel of Sullivan’s Red Ale that left his brewery was as good as the one that had gone before.

Richard Sullivan was elected to represent the people of Kilkenny in the 1820s. This supposedly put one well-known Irish political figure’s nose well and truly out of joint – Daniel O’Connell.After one particularly heated parliamentary quarrel, O’Connell even called a boycott of Sullivan’s Ale by the people of Kilkenny. But you’ll know if you’ve ever had a pint of Sullivan’s Red Ale in front of you that it can be very hard to resist, and the boycott was soon called off.

Despite this rocky start, Richard and Daniel went on to become firm friends. So good in fact, that when O’Connell was stripped of his seat in Parliament due to some underhand dealings, Sullivan was one of the few who had his back. He wrote to Daniel and offered him his seat to ensure that O’Connell’s Catholic Emancipation Act would get through Parliament.

1802MIXING BUSINESS AND POLITICSGOOD WILL, KINDNESS AND HOT SOUP

1880 was the year of ‘The Great Sullivan’s Brewery Fire’, a day that has gone down in legend among the people of Kilkenny.The story goes that the Sullivan Family took the day off brewing to attend the funeral of a recently departed family friend in a Kilkenny hilltop chapel. Leaving a funeral before all the formalities were completed was the height of bad manners. The Sullivans could see the brewery ablaze from the hillside, but could do nothing about it.

As the first flames began to lick the outside of the brewery, the alarm was raised and the local fire brigade was sent for. But The Kilkenny Fire Brigade consisted of a few volunteers, a horse and a cart and a useless, leaking hose. Due to all their good deeds over the years, the Sullivans were a tremendously popular family in Kilkenny, so men, women and children from far and wide rallied together and grabbed the nearest buckets, pales and pots, filling them with water and battling the fire. Within an hour the fire was under control and the brewery was saved, all because a community came together.

1880A COMMUNITY WORKING TOGETH1918

BLACK SHEEP AND THE LOST WAGER

After Sullivan’s Brewery closed for the final time in the early 1900s the tales of the good deeds of this Sullivan Family began to fade into memory.

Over the coming decades, the independent breweries that were once synonymous with Kilkenny began to drop off one by one, until its final working brewery sadly closed its doors in 2013. However, there wasn’t long to wait for a change of fortunes for Kilkenny-brewed ale, as 2016 saw two great families coming together to return traditional Irish brewing to its spiritual home.

The Smithwick Family in partnership with direct descendants of the Sullivan Family had a vision to re-open the once-great brewery in the city where it all began. They enlisted the help of Ian Hamilton, one of Ireland’s most eminent contemporary master-brewers. Together they are bringing artisan brewing back to Kilkenny.

If people thought that brewing in Kilkenny was dead and buried, they are in for a rude awakening…

2016

TWO GREAT FAMILIES AND THE RETURN OF SULLIVANS

WE’RE BACK AND HERE TO STAY

-

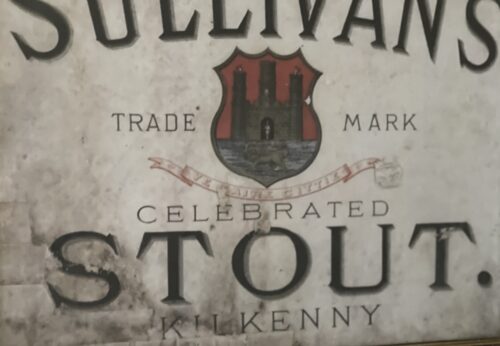

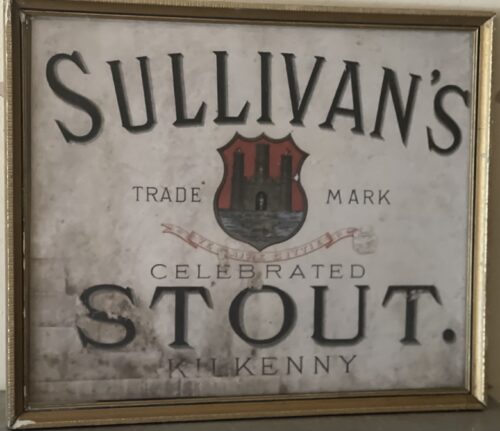

40cm x 34cm Limerick Sullivan’s Brewing Company opened for business over three hundred years ago in The Maltings on James’s Street, smack bang in the middle of Kilkenny City.

40cm x 34cm Limerick Sullivan’s Brewing Company opened for business over three hundred years ago in The Maltings on James’s Street, smack bang in the middle of Kilkenny City.Up until the early 1700s, brewing on a large scale was a rarity, this resulted in many small breweries springing up all around the country, with little or no consistency in the beer that was being produced. Back then, to guarantee that each pint was as good as the last, required brewing on a bigger, more exacting scale.

Enter Mr. Sullivan, a man of high morals, integrity and a good nose for great beer. Through his belief and hard work he established a brewery the likes of which had never been seen in Kilkenny. He only used the very best local ingredients and the very best brewing methods to ensure that every barrel of Sullivan’s Red Ale that left his brewery was as good as the one that had gone before.

Richard Sullivan was elected to represent the people of Kilkenny in the 1820s. This supposedly put one well-known Irish political figure’s nose well and truly out of joint – Daniel O’Connell.After one particularly heated parliamentary quarrel, O’Connell even called a boycott of Sullivan’s Ale by the people of Kilkenny. But you’ll know if you’ve ever had a pint of Sullivan’s Red Ale in front of you that it can be very hard to resist, and the boycott was soon called off.

Despite this rocky start, Richard and Daniel went on to become firm friends. So good in fact, that when O’Connell was stripped of his seat in Parliament due to some underhand dealings, Sullivan was one of the few who had his back. He wrote to Daniel and offered him his seat to ensure that O’Connell’s Catholic Emancipation Act would get through Parliament.

1802MIXING BUSINESS AND POLITICSGOOD WILL, KINDNESS AND HOT SOUP

1880 was the year of ‘The Great Sullivan’s Brewery Fire’, a day that has gone down in legend among the people of Kilkenny.The story goes that the Sullivan Family took the day off brewing to attend the funeral of a recently departed family friend in a Kilkenny hilltop chapel. Leaving a funeral before all the formalities were completed was the height of bad manners. The Sullivans could see the brewery ablaze from the hillside, but could do nothing about it.

As the first flames began to lick the outside of the brewery, the alarm was raised and the local fire brigade was sent for. But The Kilkenny Fire Brigade consisted of a few volunteers, a horse and a cart and a useless, leaking hose. Due to all their good deeds over the years, the Sullivans were a tremendously popular family in Kilkenny, so men, women and children from far and wide rallied together and grabbed the nearest buckets, pales and pots, filling them with water and battling the fire. Within an hour the fire was under control and the brewery was saved, all because a community came together.

1880A COMMUNITY WORKING TOGETH1918

BLACK SHEEP AND THE LOST WAGER

After Sullivan’s Brewery closed for the final time in the early 1900s the tales of the good deeds of this Sullivan Family began to fade into memory.

Over the coming decades, the independent breweries that were once synonymous with Kilkenny began to drop off one by one, until its final working brewery sadly closed its doors in 2013. However, there wasn’t long to wait for a change of fortunes for Kilkenny-brewed ale, as 2016 saw two great families coming together to return traditional Irish brewing to its spiritual home.

The Smithwick Family in partnership with direct descendants of the Sullivan Family had a vision to re-open the once-great brewery in the city where it all began. They enlisted the help of Ian Hamilton, one of Ireland’s most eminent contemporary master-brewers. Together they are bringing artisan brewing back to Kilkenny.

If people thought that brewing in Kilkenny was dead and buried, they are in for a rude awakening…

2016

TWO GREAT FAMILIES AND THE RETURN OF SULLIVANS

WE’RE BACK AND HERE TO STAY

-

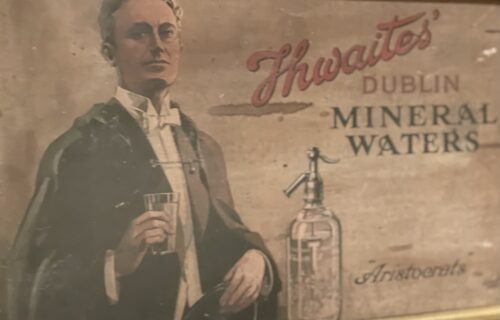

24cm x 40cm Thwaite’s Mineral Waters had been established by Dublin chemist Augustine Thwaite in the late 1700s. Thwaite’s would amalgamate with a number of other firms, including the Belfast firm of Cantrell & Cochrane, to form Mineral Water Distributers (from whence derives the name ‘MiWadi’) in 1927.

24cm x 40cm Thwaite’s Mineral Waters had been established by Dublin chemist Augustine Thwaite in the late 1700s. Thwaite’s would amalgamate with a number of other firms, including the Belfast firm of Cantrell & Cochrane, to form Mineral Water Distributers (from whence derives the name ‘MiWadi’) in 1927.Truly one of humanity’s truly great inventions is – carbonated water. How dull our taste buds would be without it! How impossible would be hangovers (so I’m told!). How . . . well . . . flat life would be!

And all down to an 18th century English Protestant minister Rev Joseph Priestly who invented soda water by accident in 1769. (What results when carbon dioxide gas is dissolved in water under pressure.)

He published a paper on it titled, ahem, Impregnating Water with Fixed Air. As you do.

Along came German-Swiss watchmaker Johann Jacob Schweppe who took Priestly’s invention and manufactured bottled carbonated mineral water. In 1792 he moved to London to develop the Schweppes business there and, in 1799, Augustine Thwaites founded Thwaites’ Soda Water in the fair city of Dublin.

It was Thwaites who first used (and patented) the term “soda water” to describe the fizzy drink. That arose from noticing that adding sodium carbonate to water greatly facilitated the absorption of carbon dioxide. Which is where the American term “soda” came from.

Those bubbles harm nothing. The carbon dioxide is always with us. It is just squashed under pressure into water. Cheers!

Carbon, from Latin carbonem, for “a coal, glowing coal, charcoal”.

-

38cm x 57cm Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.”

38cm x 57cm Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” -

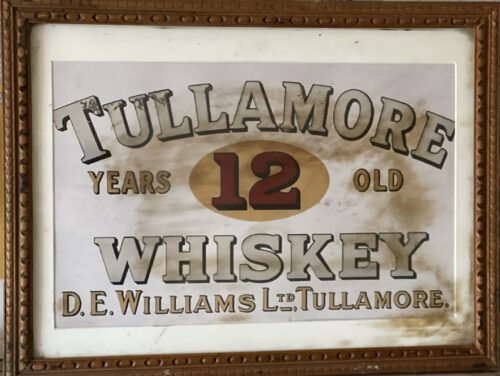

55cm x 45cm Banagher Co Offaly Tullamore D.E.W. is a brand of Irish whiskey produced by William Grant & Sons. It is the second largest selling brand of Irish whiskey globally, with sales of over 950,000 cases per annum as of 2015.The whiskey was originally produced in the Tullamore, County Offaly, Ireland, at the old Tullamore Distillery which was established in 1829. Its name is derived from the initials of Daniel E. Williams (D.E.W.), a general manager and later owner of the original distillery. In 1954, the original distillery closed down, and with stocks of whiskey running low, the brand was sold to John Powers & Son, another Irish distiller in the 1960s, with production transferred to the Midleton Distillery, County Cork in the 1970s following a merger of three major Irish distillers.In 2010, the brand was purchased by William Grant & Sons, who constructed a new distillery on the outskirts of Tullamore. The new distillery opened in 2014, bringing production of the whiskey back to the town after a break of sixty years.

55cm x 45cm Banagher Co Offaly Tullamore D.E.W. is a brand of Irish whiskey produced by William Grant & Sons. It is the second largest selling brand of Irish whiskey globally, with sales of over 950,000 cases per annum as of 2015.The whiskey was originally produced in the Tullamore, County Offaly, Ireland, at the old Tullamore Distillery which was established in 1829. Its name is derived from the initials of Daniel E. Williams (D.E.W.), a general manager and later owner of the original distillery. In 1954, the original distillery closed down, and with stocks of whiskey running low, the brand was sold to John Powers & Son, another Irish distiller in the 1960s, with production transferred to the Midleton Distillery, County Cork in the 1970s following a merger of three major Irish distillers.In 2010, the brand was purchased by William Grant & Sons, who constructed a new distillery on the outskirts of Tullamore. The new distillery opened in 2014, bringing production of the whiskey back to the town after a break of sixty years.Mick The Miller,as featured in this iconic advert, was the most famous greyhound of all time. He was born in 1926 in the village of Killeigh, County Offaly, Ireland at Millbrook House(only 5 miles from Tullamore), the home of parish curate, Fr Martin Brophy. When he was born Mick was the runt of the litter but Michael Greene, who worked for Fr Brophy, singled the little pup out as a future champion and insisted that he be allowed to rear him. With constant attention and regular exercise Mick The Miller developed into a racing machine. His first forays were on local coursing fields where he had some success but he showed his real talent on the track where he won 15 of his first 20 races.

.jpg)

In 1929 Fr Brophy decided to try Mick in English Greyhound Derby at White City, London. On his first trial-run, Mick equalled the track record. Then, in his first heat, he broke the world record, becoming the first greyhound ever to run 525 yards in under 30 seconds. Fr Brophy was inundated with offers and sold him to Albert Williams. Mick went on to win the 1929 Derby. Within a year he had changed hands again to Arundel H Kempton and won the Derby for a second time.

Over the course of his English career he won 36 of his 48 races, including the Derby (twice), the St Leger, the Cesarewitch, and the Welsh Derby. He set six new world records and two new track records. He was the first greyhound to win 19 races in a row. Several of his records went unbroken for over 40 years. He won, in total, almost £10,000 in prizemoney. But he also became the poster-dog for greyhound racing. He was a celebrity on a par with any sports person, muscisian or moviestar. The more famous he became, the more he attracted people to greyhound racing. Thousands thronged to watch him, providing a huge boost to the sport. It is said that he actually saved the sport of greyhound racing.

After retirement to stud his popularity continued. He starred in the film Wild Boy (based on his life-story) in 1934 which was shown in cinemas all across the UK. He was in huge demand on the celebrity circuit, opening shops, attending big races and even rubbing shoulder with royalty (such as the King and Queen) at charity events. When he died in 1939 aged 12, his owner donated his body to the British Natural History Museum in London. And Mick`s fame has continued ever since. In 1981 he was inducted into the American Hall of Fame (International Section). In 1990 English author Michael Tanner published a book, Mick The Miller - Sporting Icon Of the Depression. And in 2011 the people of Killeigh erected a monument on the village green to honour their most famous son. Mick The Miller is not just the most famous greyhound of all time but one of the most loved dogs that has ever lived.

-