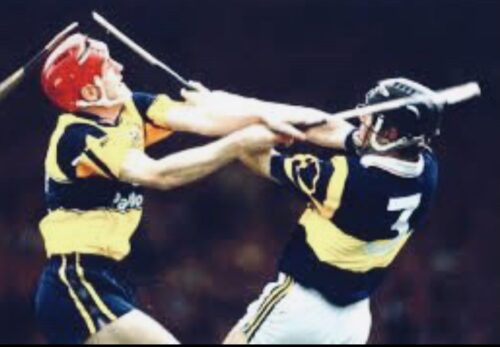

The Munster hurling final day is one of the great occasions in Irish sport.Be it Semple Stadium, the Gaelic Grounds or in Páirc Uí Chaoimh, it is a huge date on the provincial and national stage.It is a well-documented fact that on Munster final day, carloads of supporters would travel from the Glens of Antrim to Thurles to view the protagonists in action.

It’s 30 years ago now but it was a similar situation in 1990 when the two old foes collided on a scalding July day in Thurles .Tipperary had the MacCarthy Cup in their possession back then too having beaten Antrim in the All-Ireland final the previous September.Cork, on the other hand, were down in the dumps having lost to what proved to be a very poor Waterford team in 1989, a Waterford team that were subsequently hammered by Tipp in the Munster final.Cork went into the Munster final in 1990 as raging underdogs, almost no-hopers against the reigning All-Ireland champions.But it was a different Cork team that they were facing this time. In attitude as much as anything, as Teddy McCarthy and Tomás Mulcahy were both out for the provincial decider through injury.

The Canon and Gerald brought a fresh and renewed impetus to the Cork set up, brought back a few players who had been discarded and going up to Thurles there was a calm and cautiously optimistic approach.

For Cork to be in the hunt they needed a positive start to have any chance of outright victory, they needed to unsettle Tipp early on and that is exactly what transpired.

Cork started brilliantly, inspired by Jim Cashman who was a dominant figure at centre-back, while Tony O’Sullivan, later Hurler of the Year, was hugely influential at wing-forward, as the below clip from the @corkhurlers1 twitter shows.A Tipperary laden with great players like Nicky English, Pat Fox, the Bonner brothers, Declan Ryan, John Leahy and Bobby Ryan quickly realised that this was a different Cork team than the one who had went down so meekly to Waterford a year earlier.

The Cork crowd really got behind the team and as the game progressed an unlikely hero was to emerge from a small club in West Cork.

Argedeen Rangers’ Mark Foley had one of those magical days that you could only ever dream about. Everything ‘The Dentist’ touched turned to gold, there was no holding him.

Tipp couldn’t cope and the rest is history as Cork swept to one of their greatest Munster Final triumphs.

One can recall sitting in the Ryan Stand that day with Cork Examiner sports editor Tom Aherne and both of us losing the run of ourselves surrounded by Tipp supporters who were in a state of shock. Foley’s performance that day has stood the test of time as one of the greatest individual displays ever given in a Munster Final or otherwise.

But there were heroes everywhere, from Ger Cunningham out. Teddy McCarthy, John Fitzgibbon, Tomás Mulcahy, Kevin Hennessy, Denis Walsh, Ger Fitzgerald, Tony O’Sullivan to mention just a handful.

Jim Cashman had the game of his life at number six completely stifling Declan Ryan. But it was Foley’s day.

That performance would be nearly impossible to repeat but in the All Ireland final against Galway he scored 1-1 which was a major contribution as Cork regained the McCarthy Cup.

Tipp exacted revenge a year later in a Munster final replay when Jim Cashman was controversially taken out of the game.

The Cork Tipp rivalry was as intense as it ever was back then and Cork won back the Munster final in 1992.

The Cork team that day in 1990 was: G Cunningham; J Considine, D Walsh, S O’Gorman; S McCarthy, J Cashman, K McGuckin; P Buckley, B O’Sullivan; D Quirke, M Foley, T O’Sullivan; G Fitzgerald, K Hennessy, J Fitzgibbon

Scorers: Mark Foley 2-7, John Fitzgibbon 2-0, Tony O’Sullivan 0-5, Cathal Casey, Ger Fitzgerald, Kevin Hennessy, David Quirke 0-1 each.

In the All-Ireland final a short few months later Cork defeated Galway in a seven-goal thriller in Croke Park, winning in a scoreline of 5-15 to 2-21.

The Cork scorers that day were: John Fitzgibbon 2-1, Kevin Hennessy 1-4, Tomás Mulcahy 1-2, Mark Foley 1-1, Teddy McCarthy 0-3, Tony O’Sullivan 0-2, Ger Fitzgerald, Kieran McGuckin 0-1 each.

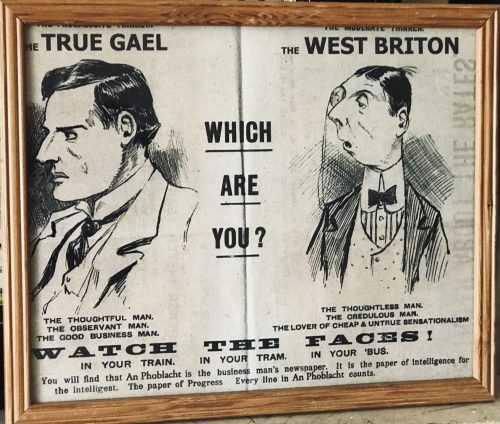

The people of Ireland are ready to become a portion of the empire, provided they be made so in reality and not in name alone; they are ready to become a kind of West Britons, if made so in benefits and justice; but if not, we are Irishmen again.Here, O'Connell was hoping that Ireland would soon become as prosperous as "North Britain" had become after 1707, but if the Union did not deliver this, then some form of Irish home rule was essential. The Dublin administration as conducted in the 1830s was, by implication, an unsatisfactory halfway house between these two ideals, and as a prosperous "West Britain" was unlikely, home rule was the rational best outcome for Ireland. "West Briton" next came to prominence in a pejorative sense during the land struggle of the 1880s. D. P. Moran, who founded The Leader in 1900, used the term frequently to describe those who he did not consider sufficiently Irish. It was synonymous with those he described as "Sourfaces", who had mourned the death of the Queen Victoria in 1901. It included virtually all Church of Ireland Protestants and those Catholics who did not measure up to his definition of "Irish Irelanders". In 1907, Canon R. S. Ross-Lewin published a collection of loyal Irish poems under the pseudonym "A County of Clare West Briton", explaining the epithet in the foreword:

Now, what is the exact definition and up-to-date meaning of that term? The holder of the title may be descended from O'Connors and O'Donelans and ancient Irish Kings. He may have the greatest love for his native land, desirous to learn the Irish language, and under certain conditions to join the Gaelic League. He may be all this, and rejoice in the victory of an Irish horse in the "Grand National", or an Irish dog at "Waterloo", or an Irish tug-of-war team of R.I.C. giants at Glasgow or Liverpool, but, if he does not at the same time hate the mere Saxon, and revel in the oft resuscitated pictures of long past periods, and the horrors of the penal laws he is a mere "West Briton", his Irish blood, his Irish sympathies go for nothing. He misses the chief qualifications to the ranks of the "Irish best", if he remains an imperialist, and sees no prospect of peace or happiness or return of prosperity in the event of the Union being severed. In this sense, Lord Roberts, Lord Charles Beresford and hundreds of others, of whom all Irishmen ought to be proud, are "West Britons", and thousands who have done nothing for the empire, under the just laws of which they live, who, perhaps, are mere descendants of Cromwell's soldiers, and even of Saxon lineage, with very little Celtic blood in their veins, are of the "Irish best".Ernest Augustus Boyd's 1924 collection Portraits: real and imaginary included "A West Briton", which gave a table of West-Briton responses to keywords:

| Word | Response |

|---|---|

| Sinn Féin | Pro-German |

| Irish | Vulgar |

| England | Mother-country |

| Green | Red |

| Nationality | Disloyalty |

| Patriotism | O.B.E. |

| Self-determination | Czecho-Slovakia |

I'm an effete, urban Irishman. I was an avid radio listener as a boy, but it was the BBC, not RTÉ. I was a West Brit from the start. ... I'm a kind of child of the Pale. ... I think I was born to succeed here [in the UK]; I have much more freedom than I had in Ireland.Wogan became a dual citizen of Ireland and the UK, and was eventually knighted by Queen Elizabeth II.

It was Richie Connor in the early 1990s who first introduced me to the concept. For the Offaly team he captained, ultimately to the 1982 All-Ireland, beating Dublin in the 1980 Leinster final had he said been their most significant achievement.

This was because winning the province represented a longer journey from where the team under Eugene McGee had started than the distance from there to the Sam Maguire.

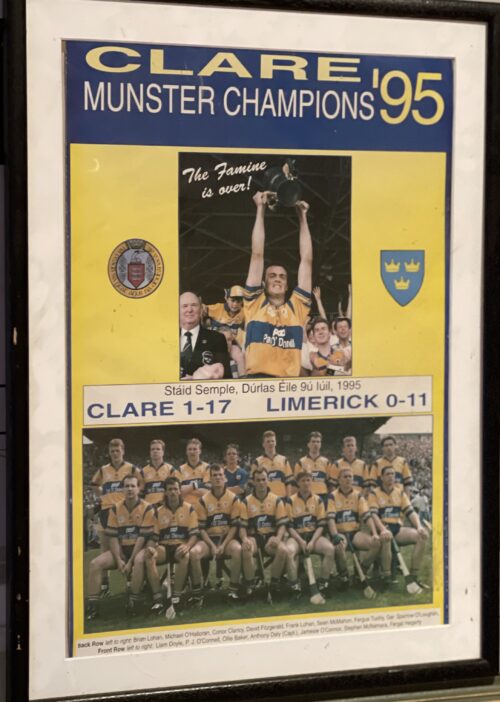

Maybe the reasoning was slightly different in Clare but it amounted to the same thing. In the few weeks that shimmered in the radiant summer of 1995 between winning Munster and the All-Ireland semi-final against Galway, manager Ger Loughnane was certainly of that view.

“In Clare, Munster is the Mount Everest. All along Munster was what was talked about. I remember stopping Nenagh on the way back from the League final and a man saying, ‘if only we could win Munster once, it would make up for everything’.

“The reaction to our winning Munster has been far greater than what would happen in other counties if they won an All-Ireland.”

Clare had got to the stage where they were being upstaged by their footballers whose first Munster title since 1917 had been sensationally won in 1992 leaving the hurlers by-passed.

Anthony Daly, prominent in 1995 as the exuberant captain of the hurlers, remembered the big-ball community’s notions. He went to support the footballers in their All-Ireland semi-final against Dublin three years previously. In a bar beforehand he was mocked for band-wagoning.

“Do you go to our matches at all,” asks Daly.

“I do, I do,” comes the response.

“And when you do, does anyone ever tell you to f*** off back to west Clare?”

Boom, boom.

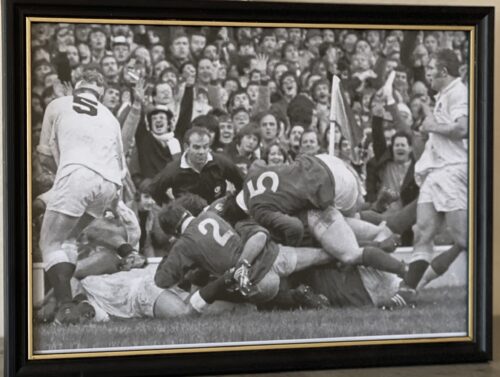

Twenty-five years ago today (Thursday) the county hurlers climbed Everest and in unexpected style. Clare had qualified for a third successive Munster final but the previous two, against Limerick and Tipperary had ended in heavy defeats.

This season would be different. Loughnane’s elevation from selector to manager crystallised the potential that his predecessor Len Gaynor had harnessed to reach Munster finals in 1993 and ‘94. They had taken the lessons of losing to a Zen level.

I remember seeing Loughnane and his selectors Mike McNamara and Tony Considine sitting in the Queens Hotel in Ennis after a league match with a fairly full-strength Tipperary.

They were super-pleased with the win, one of a number of markers laid down in a season that ended with defeat in the final against Kilkenny after which the manager famously declared that they would win Munster. The approach had been clear: find some new players, get incredibly fit and start beating likely rivals.

The winter had been a time of slog under McNamara’s fundamentalist training but the late spring with its brightening nights would be a time for sharpening the hurling and adding speed to their playbook.

“In a way the League final was the best thing that happened us,” said Loughnane after the provincial success. “All the old failings were there. We were too tense: all frenzy, no method. We were going to have to use our heads. If we’d won the League we definitely wouldn’t have won the Munster championship.”

Limerick were in a valley season between two demoralising All-Ireland final defeats but were raging favourites, having beaten Tipperary while Clare had laboured to get past Cork.

Clare also had their past, 11 Munster final defeats since the previous win in 1932 and well beaten by Limerick the previous year. The League final defeat a mere two months previously didn’t help the argument that the team had the ability to win big matches.

As a match it doesn’t look great these days. There are too many errors and too much imprecision in the play. Limerick look lethargic and off-key. They play the first half with the advantage of a strong wind but trail at half-time.

In a low-scoring, scrappy affair Clare aren’t doing themselves justice either but for a team,who had been trimmed in their previous finals they’re hanging in there for most of the first half. In other words the match isn’t getting away from them, either - which is an improvement on the recent past.

Goalkeeper Davy Fitzgerald’s expertly hit penalty edges Clare in front and tactically they have taken a grip. Fitzgerald is also excellent in goal producing a couple of saves that prevent Limerick from getting too involved.

Ollie Baker, of whom a lot had been expected when he was drafted into the team for the league, has a non-stop match, physically overshadowing the powerful Limerick pairing of Mike Houlihan and Seán O’Neill and beside him James O’Connor overcomes a difficult start and is on to everything, fast and fluent.

His six points include four from play and his only failure of marksmanship is a shot that hits the post late in the match. PJ O’Connell also gets four from play but is selected as MOTM for the job done on disorientating Ciarán Carey with his constant movement.

“I knew I had to keep Ciarán Carey away from the puck-outs,” he says afterwards, “so I kept him running around. I had done a lot of work for this and I knew I would not get winded or caught for pace. I just kept running him and I could see it was having an effect.”

Seán McMahon broke his collarbone in the semi-final against Cork and returns for the final a week earlier than ideal but thrives as Gary Kirby, who had destroyed him a year previously, falters.

Clare’s grip tightens. Limerick manage just four points in the second half, as the winners pull away steadily.

It’s a stunning win - a tribute to Loughnane, who in the years before the acid erosion of controversies and fallings-out is a charismatic leader, whose prescriptions were single-mindedly adopted by the players and embraced by the Clare public.

“The feeling was that at long last a barrier had been broken,” he said before the All-Ireland semi-final. “The atmosphere in the county was incredible. It was great for the footballers a couple of years ago but they hadn’t been waiting and failing the way the hurlers had for years and years and years. It was very emotional, more because it was so unexpected after Limerick trouncing Clare last year. A good few didn’t even go to Thurles because they were afraid.”

For those few weeks, they are on the cusp of history, something almost spiritual. In the week before the Galway semi-final, Loughnane recounted how he had happened upon a car accident.

He hurries to check on the elderly motorist, who is shaken but not injured. They are joined by a third man.

“This other fella is looking at me and says, ‘Ger, isn’t it?’ I said, ‘yes’ and he says to the poor old man: ‘It’s Ger Loughnane! Isn’t that enough to make you better?’”

A nurse arrives with the ambulance and pauses to comment.

“I hope everything’s right for Sunday.”

Need she have asked in that summer of summers?