-

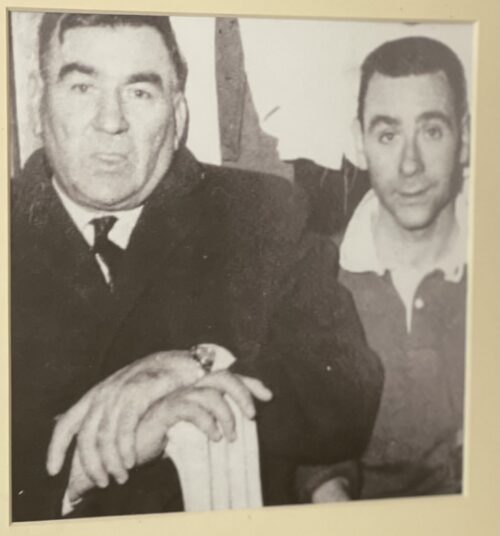

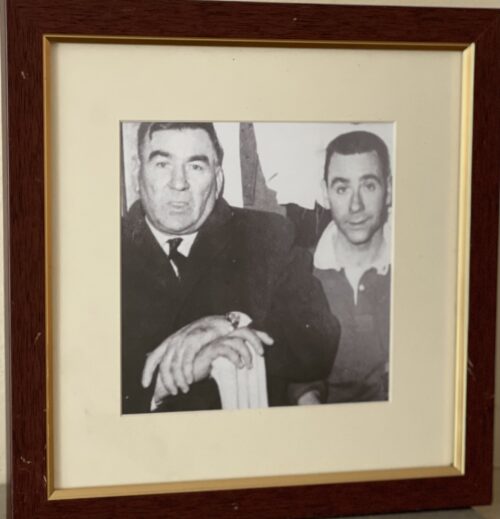

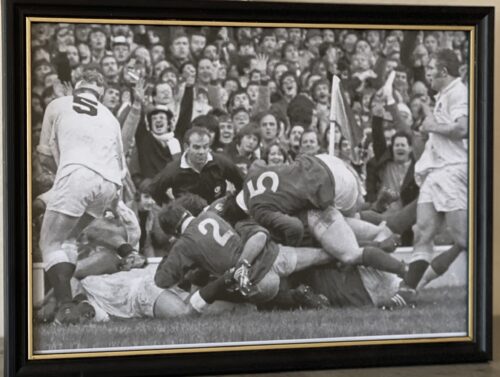

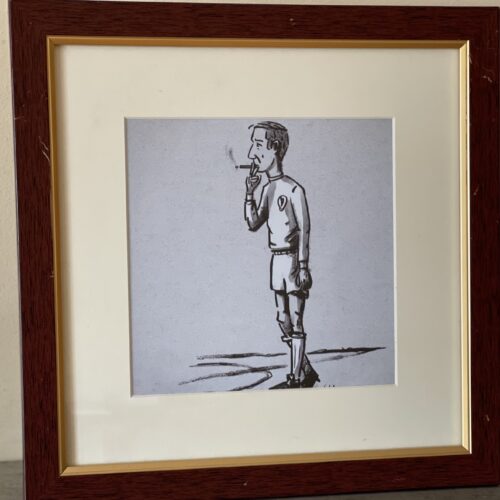

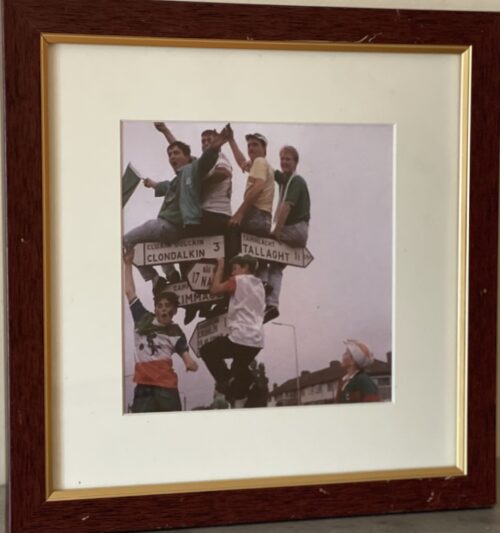

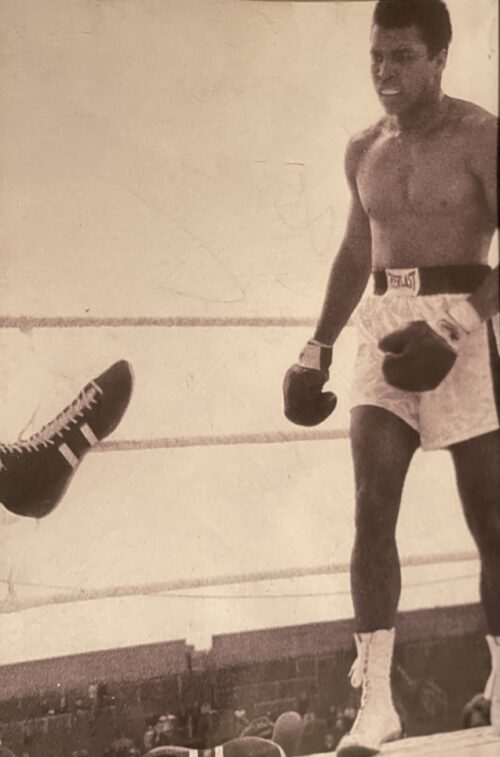

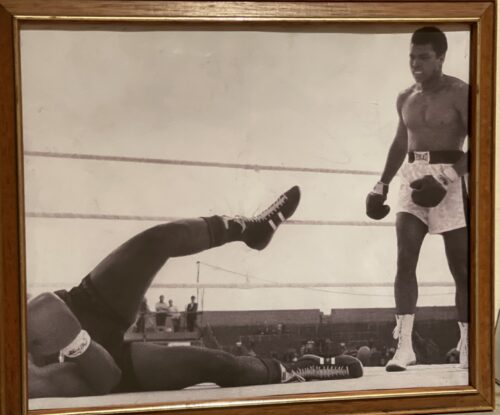

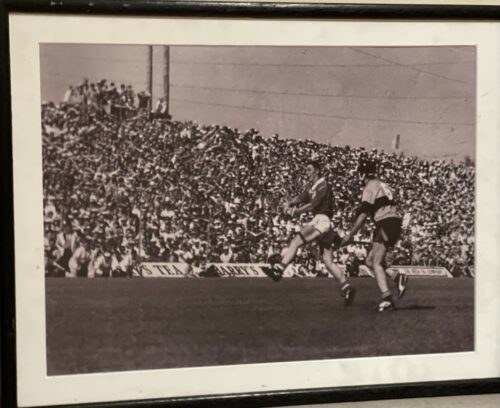

Gerry ‘Ginger' McLoughlin – better known as ‘Locky' in his native Limerick - was instrumental in winning the 1982 Triple Crown, Ireland's first since 1949. Below, ‘Locky' tells of his flirtation with the priesthood, Limerick's rugby rivalries and great players, his call-up to international rugby and the fateful tour to apartheid South Africa which impacted on his teaching career By Dave McMahon There are few contenders for the most memorable Irish try of the last 50 years. A generation who remember the days of black and white television will cite Pat Casey's ‘criss-cross' try against England at Twickenham in 1964 when Mike Gibson's searing break gave Jerry Walsh the opportunity to deliver the decisive reverse pass. Gordon Hamilton's superb burst to score in the Lansdowne Road corner against Australia in the 1991 World Cup ranks high in the list – a try that rarely gets the credit it deserves because of Michael Lynagh's instant riposte. Nearer the present day, the delayed October Six-Nations game against England in 2001 saw Keith Wood score one of the great forwards inspired try's against the auld enemy at Lansdowne Road. A try, indeed, which gave purists as much pleasure as any, with the pack orchestrating the score with military precision. The line-out throw from Wood; Galwey's clean take; Foley's magical hands; Eric Miller doing just enough to create the running channel; Wood's powerful burst through Neil Back's tackle for the touchdown. And then, you had Locky's try against England at Twickenham in the Triple Crown winning year of 1982 – a different class! In recalling 1982, it's Gerry McLoughlin's try that represents the defining moment of Ireland's first Triple Crown winning year since 1949. Ollie Campbell's touchline conversion of McLoughlin's try (pictured left) helped Ireland to a 16-15 victory and an ultimately successful Triple Crown decider against Scotland two weeks later. Three generations of Irish rugby heroes had come and gone without Triple Crown success – McBride, Kiernan, Dawson, O'Reilly, Gibson, and Goodall. Gerry McLoughlin's try helped create history, and he isn't slow to trumpet his role in '82.“At the time, I was misquoted as saying I dragged the Irish pack over the line with me.In fact, I dragged the entire Irish and English forwards across the line that day! Also, I never got the credit for creating the free which led to my try. As Steve Smith was about to put-in at an English scrum, I whispered to Ciaran Fitzgerald that I intended to pull the scrum, which I did successfully with the result that Smith was penalised for crooked-in. After the free was taken, I took over.” It was a tremendous year for McLoughlin during a rugby career which had its share of heartbreak as well as some glorious highs. “As a young man, I dabbled with hurling and gaelic football as a full-back or full-forward with St. Patrick's CBS. I had no great skill at either code; I simply mullocked and laid into guys. My destiny was certainly never to be a skillful All-Ireland winning hurler with Limerick. Rugby was always going to be my game. “Brian O'Brien got three Irish caps in 1968 and I regarded him as a hero, so it was always on that I should join Shannon, while my late father, Mick, had won Transfield Cup medals with the parish side. Joining Shannon at 16, my bulk and size immediately saw me go into the front-row where I had Michael Noel Ryan, who had captained the first-ever Shannon team to win the Munster Senior Cup, as a sound mentor. “Frankly, at the time, I didn't plan on a rugby career as I had other designs on my life. As soon as I entered Sexton Street CBS, my admiration for the role that the Christian Brothers played in Irish society saw me develop a vocation to become a Christian Brother. I spent a 3 year novitiate between Carriglea Park in Dun Laoghaire and St. Helens in Booterstown and was within 3 weeks of taking my vows of poverty, chastity and obedience before deciding that I wanted to opt out. “Had I taken the vows, I would have entered a world where there was no television, no newspapers and would not be able to take holidays or see my family for the best part of five years. That's the way it was in those days. I was at a young impressionable age and, in the end, I got stage fright and returned to Sexton Street as a pupil. “At 18, I was in the Shannon senior-cup team and I knew that I had some ability. After Sexton Street, I went to UCG to do my BA and that gave me the opportunity of further developing my rugby skills as I joined Ciaran Fitzgerald in the Colleges senior front-row. I won a handful of senior caps with Connacht who were not very successful at the time. The highlight of my Connacht career came when we ended a near 10-year losing run by beating, believe it or not, Spain by 7-3 in 1973. I played with some decent players in my days with Connacht, Mick Molloy and Leo Galvin were often in the second-row, while Mick Casserly was probably the best wing-forward never to be capped by Ireland.” After graduating from UCG, and the successful completion of a teacher-training degree with UCC, McLoughlin returned to his alma mater Sexton Street CBS as an Economics teacher in 1973 – and to the front-row in a Shannon senior-team that was about to make it's mark on the Irish rugby scene. “In those days, the rivalry between Limerick clubs was intense. Young Munster was a proud working-class club that commanded tremendous support and playing against them, especially in Greenfields, was often tougher than the Cardiff Arms Park. Reputations counted for nothing. You ignored hamstrings, cuts, strains and blood – you earned respect against them.” “Of course, Garryowen set the standard with their huge number of Munster Cup victories. In my time, they had a great full-back in Larry Moloney. Just four caps with Ireland was no reward for his ability. Despite spending 13 years of my life in Wales, the edge between Shannon and Garryowen is deeply engrained in my brain. Time hasn't diminished that rivalry. “People speak of Limerick rugby and the syndrome of doctor and docker playing side by side. That was certainly the case with Garryowen. Mick Lucey and Len Harty were doctors who played in the light blues three-quarter line in the late 60's. Then, you often had Dr. Jim Molloy playing in the Garryowen pack alongside Tom Carroll who was a Limerick docker. To this day, I maintain that Carroll was both the toughest and technically most proficient prop-forward I ever encountered. Tom was not much more than 13 stone, yet I never got the better of him. “In my early days with Shannon, we hardly rated on the rugby map. Teams like Trinity and Wanderers didn't want games against us. Garryowen were the standard bearers in Limerick and our aim was to become as good as them. After I returned from UCG in 1973, Shannon, with Brian O'Brien pulling the strings, had begun to assemble a powerful team. Brendan Foley was a fine second-row and an inspirational captain. Colm Tucker was the best ball-carrying wing-forward I ever played with. Colm was good enough to play in two tests for the Lions against South Africa in 1980, yet he was only capped on three occasions by Ireland. That was an absolute joke. “You would go a long way before finding better club forwards than my brother Mick, Eddie Price, Johnny Barry and Noel Ryan. Later, Niall O'Donovan came through as an outstanding number eight. Noel Ryan, indeed, was such a good loose-head prop that I played all my games for Shannon and, subsequently, Ireland at tight-head, while my entire career with Munster, and a handful of games with the Lions in 1983, was in the loose-head position. Playing on either side of the scrum never presented problems as the emphasis in training with Shannon was always on having a powerful scrummage as a starting-point.” Just six months after representing Connacht against Spain, McLoughlin won his first Munster ‘cap' in a fiery encounter against Argentina at Thomond Park. That was the start of a long interprovincial career which lasted from 1983 to 1987. An ever-present in the Munster team, the breakthrough to International level proved daunting and is the source of fiery comment from McLoughlin. “As I was a regular with Munster, I was asked to submit a CV by the IRFU to facilitate any calling to International level. I did all the right things. I deducted a year from my age with the result that my birth date changed from 11 June 1951 to 11 June 1952. I added a half-inch to my height to make sure that I came in as a sturdy six footer. I weighed 13 stone, 11 ounces those days and I remember sticking 7 pounds of lead into my jockstrap at a formal weigh-in to hit the 14 stone, 4 ounce mark. Still, the call to international representation was light years away. Ciaran Fitzgerald knew my correct age, but kept it quiet for years before revealing all to the IRFU one evening when he had a few too many. At that stage, it didn't matter. “The selection system was just a joke with two Leinster, two Ulster and a solitary Munster selector, with Connacht having no representation at all. To this day, I often wonder how Ciaran Fitzgerald was ever capped. I played some fine rugby for Munster over many years, yet I never came close to making the International scene and I doubt that I would have were it not for Munster beating the All Blacks in 1978. The selectors found it impossible to ignore us after that. I was also very lucky that Brian O'Brien eventually came through as an Irish selector. For years, he kept me in a ‘job', and I kept him in a ‘job'.” Munster's victory over New Zealand remains the most emotional game of McLoughlin's career. “It wasn't a fluke by any means as that was a superb Munster team. For starters, the usual Cork/Limerick selectorial carve-up didn't apply as twelve of the Munster team picked themselves. We had leaders and quality players all over the field. Wardie (Tony Ward) was under pressure all day, but still managed to kick brilliantly for position; Canniffe gave him a great service; Dennison and Barrett never stopped tackling; Larry Moloney was himself at full-back; Andy Haden might have won the line-out battle, but we matched the All Blacks forwards everywhere else; in the end, we fully deserved our 12-0 victory. “After that success over New Zealand, I was totally focused on making the step up to International level. I was often asked for tips by budding prop-forwards, but I never revealed anything useful in case the younger man got better than me. You spend all your career striving to get to the top and the last thing you wanted was someone to get ahead of you in the race. I had to be both dedicated and selfish.” Just three months after beating New Zealand and a successful final-trial outing with the probables, McLoughlin made his international debut against France. He may have been listed as ‘G.A.J. McLoughlin' on the match programme, but Limerick rugby followers still called him ‘Locky' – one of their own! Woe betide the fate of any Dublin hack that resorted to ‘Ginger'. Nearly 30 years after his International debut, he is still ‘Locky' in Limerick, but the metropolitan media continually refer to him as ‘Ginger'. But what's in a name? Some 10 years ago an almost fatal blow was struck against the ‘Locky' constituency. With the future of Connacht rugby under threat, a protest march to IRFU headquarters at Lansdowne Road was made. Remembering his youthful days in UCG and that famous victory over Spain, Gerry McLoughlin was at the forefront of the parade with a banner which read “Ginger supports Connacht rugby”. Locky or Ginger? Take your pick. If the Triple Crown and Munster's victory over the All Blacks were career highlights, McLoughlin's decision to tour South Africa with Ireland in 1981 cast a long shadow over his life. “I was teaching in Sexton Street at the time and initially got approval from the school to travel. However, just a week before we were due to depart, a change of management took place within the school and my permission to travel was withdrawn. It left me with a very difficult decision to make. I was married with a young family, but I dearly wanted to represent my country. Also, I felt that South Africa were making advances on apartheid. Errol Tobias, in fact, became the first non-white player to wear the Springboks jersey in a full-international against Ireland. In the end, I resigned my teaching position and travelled with Ireland.” In rugby terms, McLoughlin's decision to travel was justified as he regained his Irish place and played in both tests. However, it was altogether different on a personal level. “On my return from South Africa, I was advised that I had a solid legal case against my former employers in Sexton Street but I decided against taking any action as I had a great love of the Christian Brothers and had witnessed the benefits which their dedication gave to generations of children. They were put under severe pressure at the time as apartheid was a political and social time-bomb.” McLoughlin is far less forgiving when it came to the IRFU post-South Africa. “I wrote to every school in the country and couldn't get an interview, never mind get a job. The IRFU had plenty of people in positions of power, but the support from that quarter was nil. Ray McLoughlin (no relation) and Mick Molloy did offer considerable help at the time. Other than that, I was largely left to fend for myself.” From a remove of nearly 30 years, McLoughlin is philosophical. “It was my decision to travel to South Africa – I had to accept the consequences.” A part-time job teaching in the Municipal Institute of Technology followed, but that was never going to be enough to support a young family. The painful decision to emigrate to Wales was taken, after recession forced McLoughlin to close his pub – aptly named The Triple Crown – which he owned for five years. “In all, I spent 13 years in Wales, teaching in Gilfach Goch near Pontypridd during the day and running a pub in the evenings before deciding to return to Ireland. At the moment, my daughter Orla, who is getting married next August, is based in Limerick, while my three sons, Cian, Fionn and Emmet are in Wales where they spent so much of their youth.” Nowadays, living in Garryowen in the shade of St. John's Cathedral, Gerry McLoughlin enjoys a contented social and political life. “I was elected to the Limerick City Council as an Independent in 2004, before subsequently joining the Labour party. I had always admired the social vision of the late Jim Kemmy, so the move to Labour was a natural progression for me. “On a professional level, I'm energised by the day job as a social needs assistant at St. Mary's Boys School in the heart of the parish. I'm a lifetime non-smoker and I haven't touched alcohol in the last 14 years. I have a hectic political schedule, but I also find plenty of time to engage in worthwhile community work. “Recently, we formed an under 13/14 girls soccer club in Garryowen and I'm involved as Treasurer. Also, I coach St. Mary's under-age teens in rugby on Sunday mornings, while I have a similar role in soccer coaching with Star Rovers youngsters. Nowadays, my ambition is to give every child the opportunity to kick a ball.” The man who once propped against the famous Pontypool front-row confesses to a surprising social outlet: “I had a knee replacement operation in 2004 and that gave me the freedom to enjoy ballroom dancing on at least three evenings a week. It's wonderful for social relaxation”. Gerry McLoughlin has few, if any, regrets about his rugby career. “In the current era, I might have won 50 instead of 18 caps, but I have the memory of never losing in an Irish jersey at Lansdowne Road and I wouldn't change the Triple Crown success or beating the All Blacks for anything. Would I do things differently? Possibly. I might have deducted two years from my age if I was starting all over again!”

Gerry ‘Ginger' McLoughlin – better known as ‘Locky' in his native Limerick - was instrumental in winning the 1982 Triple Crown, Ireland's first since 1949. Below, ‘Locky' tells of his flirtation with the priesthood, Limerick's rugby rivalries and great players, his call-up to international rugby and the fateful tour to apartheid South Africa which impacted on his teaching career By Dave McMahon There are few contenders for the most memorable Irish try of the last 50 years. A generation who remember the days of black and white television will cite Pat Casey's ‘criss-cross' try against England at Twickenham in 1964 when Mike Gibson's searing break gave Jerry Walsh the opportunity to deliver the decisive reverse pass. Gordon Hamilton's superb burst to score in the Lansdowne Road corner against Australia in the 1991 World Cup ranks high in the list – a try that rarely gets the credit it deserves because of Michael Lynagh's instant riposte. Nearer the present day, the delayed October Six-Nations game against England in 2001 saw Keith Wood score one of the great forwards inspired try's against the auld enemy at Lansdowne Road. A try, indeed, which gave purists as much pleasure as any, with the pack orchestrating the score with military precision. The line-out throw from Wood; Galwey's clean take; Foley's magical hands; Eric Miller doing just enough to create the running channel; Wood's powerful burst through Neil Back's tackle for the touchdown. And then, you had Locky's try against England at Twickenham in the Triple Crown winning year of 1982 – a different class! In recalling 1982, it's Gerry McLoughlin's try that represents the defining moment of Ireland's first Triple Crown winning year since 1949. Ollie Campbell's touchline conversion of McLoughlin's try (pictured left) helped Ireland to a 16-15 victory and an ultimately successful Triple Crown decider against Scotland two weeks later. Three generations of Irish rugby heroes had come and gone without Triple Crown success – McBride, Kiernan, Dawson, O'Reilly, Gibson, and Goodall. Gerry McLoughlin's try helped create history, and he isn't slow to trumpet his role in '82.“At the time, I was misquoted as saying I dragged the Irish pack over the line with me.In fact, I dragged the entire Irish and English forwards across the line that day! Also, I never got the credit for creating the free which led to my try. As Steve Smith was about to put-in at an English scrum, I whispered to Ciaran Fitzgerald that I intended to pull the scrum, which I did successfully with the result that Smith was penalised for crooked-in. After the free was taken, I took over.” It was a tremendous year for McLoughlin during a rugby career which had its share of heartbreak as well as some glorious highs. “As a young man, I dabbled with hurling and gaelic football as a full-back or full-forward with St. Patrick's CBS. I had no great skill at either code; I simply mullocked and laid into guys. My destiny was certainly never to be a skillful All-Ireland winning hurler with Limerick. Rugby was always going to be my game. “Brian O'Brien got three Irish caps in 1968 and I regarded him as a hero, so it was always on that I should join Shannon, while my late father, Mick, had won Transfield Cup medals with the parish side. Joining Shannon at 16, my bulk and size immediately saw me go into the front-row where I had Michael Noel Ryan, who had captained the first-ever Shannon team to win the Munster Senior Cup, as a sound mentor. “Frankly, at the time, I didn't plan on a rugby career as I had other designs on my life. As soon as I entered Sexton Street CBS, my admiration for the role that the Christian Brothers played in Irish society saw me develop a vocation to become a Christian Brother. I spent a 3 year novitiate between Carriglea Park in Dun Laoghaire and St. Helens in Booterstown and was within 3 weeks of taking my vows of poverty, chastity and obedience before deciding that I wanted to opt out. “Had I taken the vows, I would have entered a world where there was no television, no newspapers and would not be able to take holidays or see my family for the best part of five years. That's the way it was in those days. I was at a young impressionable age and, in the end, I got stage fright and returned to Sexton Street as a pupil. “At 18, I was in the Shannon senior-cup team and I knew that I had some ability. After Sexton Street, I went to UCG to do my BA and that gave me the opportunity of further developing my rugby skills as I joined Ciaran Fitzgerald in the Colleges senior front-row. I won a handful of senior caps with Connacht who were not very successful at the time. The highlight of my Connacht career came when we ended a near 10-year losing run by beating, believe it or not, Spain by 7-3 in 1973. I played with some decent players in my days with Connacht, Mick Molloy and Leo Galvin were often in the second-row, while Mick Casserly was probably the best wing-forward never to be capped by Ireland.” After graduating from UCG, and the successful completion of a teacher-training degree with UCC, McLoughlin returned to his alma mater Sexton Street CBS as an Economics teacher in 1973 – and to the front-row in a Shannon senior-team that was about to make it's mark on the Irish rugby scene. “In those days, the rivalry between Limerick clubs was intense. Young Munster was a proud working-class club that commanded tremendous support and playing against them, especially in Greenfields, was often tougher than the Cardiff Arms Park. Reputations counted for nothing. You ignored hamstrings, cuts, strains and blood – you earned respect against them.” “Of course, Garryowen set the standard with their huge number of Munster Cup victories. In my time, they had a great full-back in Larry Moloney. Just four caps with Ireland was no reward for his ability. Despite spending 13 years of my life in Wales, the edge between Shannon and Garryowen is deeply engrained in my brain. Time hasn't diminished that rivalry. “People speak of Limerick rugby and the syndrome of doctor and docker playing side by side. That was certainly the case with Garryowen. Mick Lucey and Len Harty were doctors who played in the light blues three-quarter line in the late 60's. Then, you often had Dr. Jim Molloy playing in the Garryowen pack alongside Tom Carroll who was a Limerick docker. To this day, I maintain that Carroll was both the toughest and technically most proficient prop-forward I ever encountered. Tom was not much more than 13 stone, yet I never got the better of him. “In my early days with Shannon, we hardly rated on the rugby map. Teams like Trinity and Wanderers didn't want games against us. Garryowen were the standard bearers in Limerick and our aim was to become as good as them. After I returned from UCG in 1973, Shannon, with Brian O'Brien pulling the strings, had begun to assemble a powerful team. Brendan Foley was a fine second-row and an inspirational captain. Colm Tucker was the best ball-carrying wing-forward I ever played with. Colm was good enough to play in two tests for the Lions against South Africa in 1980, yet he was only capped on three occasions by Ireland. That was an absolute joke. “You would go a long way before finding better club forwards than my brother Mick, Eddie Price, Johnny Barry and Noel Ryan. Later, Niall O'Donovan came through as an outstanding number eight. Noel Ryan, indeed, was such a good loose-head prop that I played all my games for Shannon and, subsequently, Ireland at tight-head, while my entire career with Munster, and a handful of games with the Lions in 1983, was in the loose-head position. Playing on either side of the scrum never presented problems as the emphasis in training with Shannon was always on having a powerful scrummage as a starting-point.” Just six months after representing Connacht against Spain, McLoughlin won his first Munster ‘cap' in a fiery encounter against Argentina at Thomond Park. That was the start of a long interprovincial career which lasted from 1983 to 1987. An ever-present in the Munster team, the breakthrough to International level proved daunting and is the source of fiery comment from McLoughlin. “As I was a regular with Munster, I was asked to submit a CV by the IRFU to facilitate any calling to International level. I did all the right things. I deducted a year from my age with the result that my birth date changed from 11 June 1951 to 11 June 1952. I added a half-inch to my height to make sure that I came in as a sturdy six footer. I weighed 13 stone, 11 ounces those days and I remember sticking 7 pounds of lead into my jockstrap at a formal weigh-in to hit the 14 stone, 4 ounce mark. Still, the call to international representation was light years away. Ciaran Fitzgerald knew my correct age, but kept it quiet for years before revealing all to the IRFU one evening when he had a few too many. At that stage, it didn't matter. “The selection system was just a joke with two Leinster, two Ulster and a solitary Munster selector, with Connacht having no representation at all. To this day, I often wonder how Ciaran Fitzgerald was ever capped. I played some fine rugby for Munster over many years, yet I never came close to making the International scene and I doubt that I would have were it not for Munster beating the All Blacks in 1978. The selectors found it impossible to ignore us after that. I was also very lucky that Brian O'Brien eventually came through as an Irish selector. For years, he kept me in a ‘job', and I kept him in a ‘job'.” Munster's victory over New Zealand remains the most emotional game of McLoughlin's career. “It wasn't a fluke by any means as that was a superb Munster team. For starters, the usual Cork/Limerick selectorial carve-up didn't apply as twelve of the Munster team picked themselves. We had leaders and quality players all over the field. Wardie (Tony Ward) was under pressure all day, but still managed to kick brilliantly for position; Canniffe gave him a great service; Dennison and Barrett never stopped tackling; Larry Moloney was himself at full-back; Andy Haden might have won the line-out battle, but we matched the All Blacks forwards everywhere else; in the end, we fully deserved our 12-0 victory. “After that success over New Zealand, I was totally focused on making the step up to International level. I was often asked for tips by budding prop-forwards, but I never revealed anything useful in case the younger man got better than me. You spend all your career striving to get to the top and the last thing you wanted was someone to get ahead of you in the race. I had to be both dedicated and selfish.” Just three months after beating New Zealand and a successful final-trial outing with the probables, McLoughlin made his international debut against France. He may have been listed as ‘G.A.J. McLoughlin' on the match programme, but Limerick rugby followers still called him ‘Locky' – one of their own! Woe betide the fate of any Dublin hack that resorted to ‘Ginger'. Nearly 30 years after his International debut, he is still ‘Locky' in Limerick, but the metropolitan media continually refer to him as ‘Ginger'. But what's in a name? Some 10 years ago an almost fatal blow was struck against the ‘Locky' constituency. With the future of Connacht rugby under threat, a protest march to IRFU headquarters at Lansdowne Road was made. Remembering his youthful days in UCG and that famous victory over Spain, Gerry McLoughlin was at the forefront of the parade with a banner which read “Ginger supports Connacht rugby”. Locky or Ginger? Take your pick. If the Triple Crown and Munster's victory over the All Blacks were career highlights, McLoughlin's decision to tour South Africa with Ireland in 1981 cast a long shadow over his life. “I was teaching in Sexton Street at the time and initially got approval from the school to travel. However, just a week before we were due to depart, a change of management took place within the school and my permission to travel was withdrawn. It left me with a very difficult decision to make. I was married with a young family, but I dearly wanted to represent my country. Also, I felt that South Africa were making advances on apartheid. Errol Tobias, in fact, became the first non-white player to wear the Springboks jersey in a full-international against Ireland. In the end, I resigned my teaching position and travelled with Ireland.” In rugby terms, McLoughlin's decision to travel was justified as he regained his Irish place and played in both tests. However, it was altogether different on a personal level. “On my return from South Africa, I was advised that I had a solid legal case against my former employers in Sexton Street but I decided against taking any action as I had a great love of the Christian Brothers and had witnessed the benefits which their dedication gave to generations of children. They were put under severe pressure at the time as apartheid was a political and social time-bomb.” McLoughlin is far less forgiving when it came to the IRFU post-South Africa. “I wrote to every school in the country and couldn't get an interview, never mind get a job. The IRFU had plenty of people in positions of power, but the support from that quarter was nil. Ray McLoughlin (no relation) and Mick Molloy did offer considerable help at the time. Other than that, I was largely left to fend for myself.” From a remove of nearly 30 years, McLoughlin is philosophical. “It was my decision to travel to South Africa – I had to accept the consequences.” A part-time job teaching in the Municipal Institute of Technology followed, but that was never going to be enough to support a young family. The painful decision to emigrate to Wales was taken, after recession forced McLoughlin to close his pub – aptly named The Triple Crown – which he owned for five years. “In all, I spent 13 years in Wales, teaching in Gilfach Goch near Pontypridd during the day and running a pub in the evenings before deciding to return to Ireland. At the moment, my daughter Orla, who is getting married next August, is based in Limerick, while my three sons, Cian, Fionn and Emmet are in Wales where they spent so much of their youth.” Nowadays, living in Garryowen in the shade of St. John's Cathedral, Gerry McLoughlin enjoys a contented social and political life. “I was elected to the Limerick City Council as an Independent in 2004, before subsequently joining the Labour party. I had always admired the social vision of the late Jim Kemmy, so the move to Labour was a natural progression for me. “On a professional level, I'm energised by the day job as a social needs assistant at St. Mary's Boys School in the heart of the parish. I'm a lifetime non-smoker and I haven't touched alcohol in the last 14 years. I have a hectic political schedule, but I also find plenty of time to engage in worthwhile community work. “Recently, we formed an under 13/14 girls soccer club in Garryowen and I'm involved as Treasurer. Also, I coach St. Mary's under-age teens in rugby on Sunday mornings, while I have a similar role in soccer coaching with Star Rovers youngsters. Nowadays, my ambition is to give every child the opportunity to kick a ball.” The man who once propped against the famous Pontypool front-row confesses to a surprising social outlet: “I had a knee replacement operation in 2004 and that gave me the freedom to enjoy ballroom dancing on at least three evenings a week. It's wonderful for social relaxation”. Gerry McLoughlin has few, if any, regrets about his rugby career. “In the current era, I might have won 50 instead of 18 caps, but I have the memory of never losing in an Irish jersey at Lansdowne Road and I wouldn't change the Triple Crown success or beating the All Blacks for anything. Would I do things differently? Possibly. I might have deducted two years from my age if I was starting all over again!” -

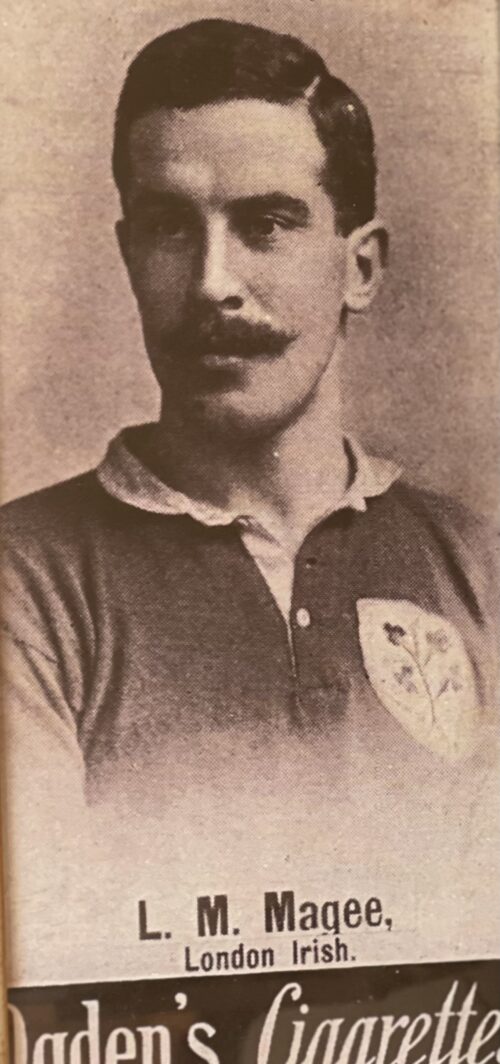

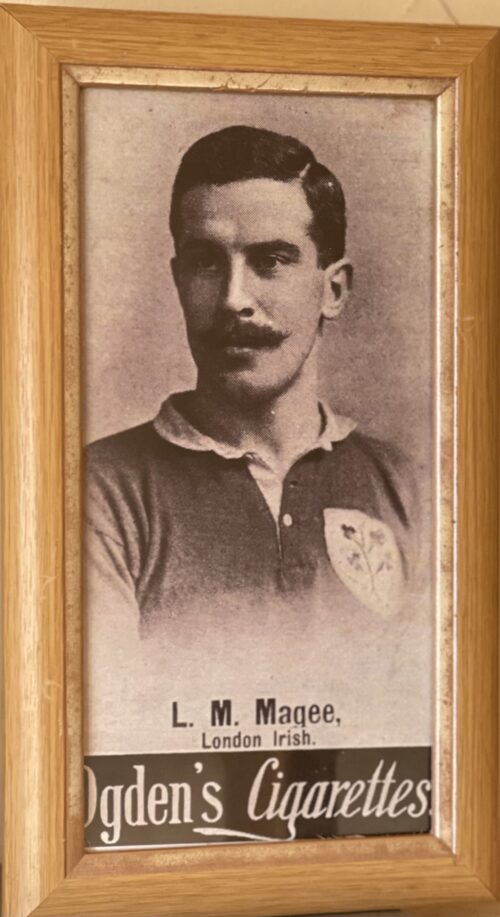

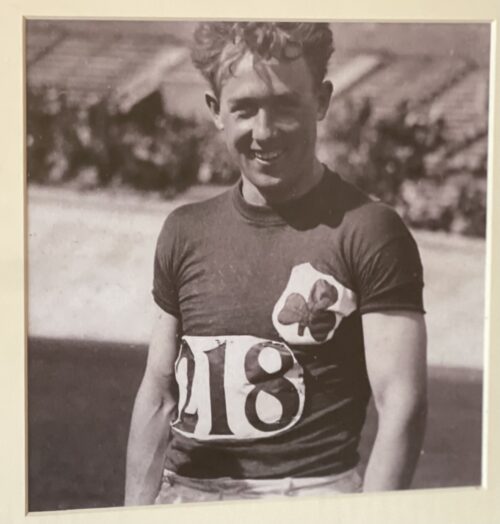

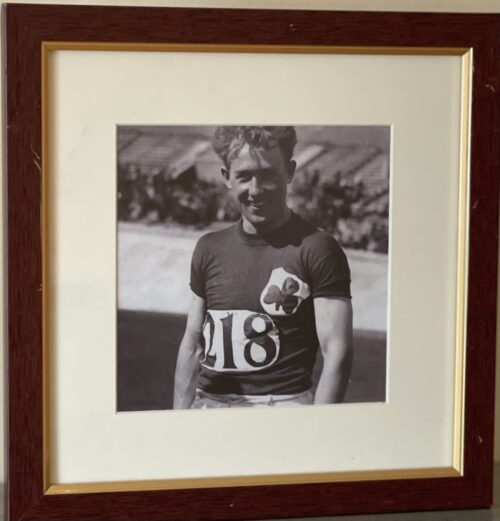

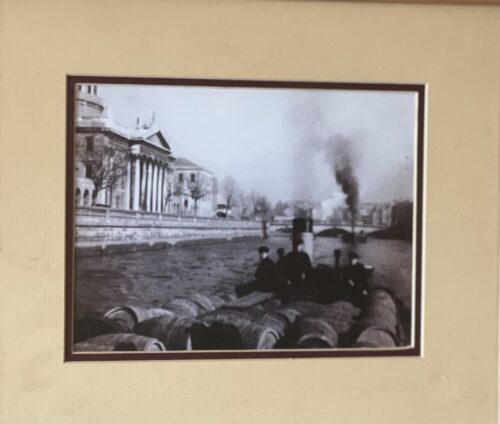

35cm x 20cm Dublin Aloysius Mary "Louis" Magee (1 May 1874 – 4 April 1945)was an Irish rugby union halfback. Magee played club rugby for Bective Rangers and London Irish and played international rugby for Ireland and was part of the British Isles team in their 1896 tour of South Africa. Magee was capped 27 times for Ireland, ten as captain, and won two Championships, leading Ireland to a Triple Crownwin in the 1899 Home Nations Championship. Magee was one of the outstanding half backs of world rugby prior to 1914, and is credited as being a driving force in turning Ireland from a no-hope team into one that commanded respect.

35cm x 20cm Dublin Aloysius Mary "Louis" Magee (1 May 1874 – 4 April 1945)was an Irish rugby union halfback. Magee played club rugby for Bective Rangers and London Irish and played international rugby for Ireland and was part of the British Isles team in their 1896 tour of South Africa. Magee was capped 27 times for Ireland, ten as captain, and won two Championships, leading Ireland to a Triple Crownwin in the 1899 Home Nations Championship. Magee was one of the outstanding half backs of world rugby prior to 1914, and is credited as being a driving force in turning Ireland from a no-hope team into one that commanded respect.Rugby career

Magee came from a well known sporting family. His eldest brother Joseph Magee was also an international rugby player for Ireland, while another brother James played cricket for Ireland. His brother-in-law, Tommy Little, played rugby for Ireland between 1898 and 1901.Magee played almost the entirety of his rugby for club team Bective Rangers, as did both his brothers. In 1898, while in London, Magee was approached by newly formed club, London Irish, to play for the first team. When Magee accepted, his presence in the team helped recruit other countrymen to join the exile club, and is seen as a major catalyst in the success of the club.Early international career

Magee first played international rugby during the 1895 Home Nations Championship in an encounter with England. Magee was selected along with his brother Joseph, but Joseph's international career ended after only two games, playing in only the first two matches of the 1895 season. Although Ireland narrowly lost the opening game, Magee scored the only points for Ireland when he scored his first international try. Magee was reselected for the next two games of the Championship, Ireland losing both narrowly in two tight matches which saw Ireland end bottom of the table for the season.British Isles tour

1896 was a turn around in fortunes for Ireland, beating England and Wales and drawing 0–0 with Scotland, giving Ireland its second Championship in three years. Magee played in all three games of the season making him a Championship winning player. Towards the end of the 1896 season, Magee was approached by Johnny Hammond to join his British Isles team on their tour of South Africa. Magee accepted, and was joined on the tour by his brother James, who was also a member of Bective Rangers. The tour was notable for the large contingent of Irish players, who had been poorly represented on previous tours. The other Irish players being Thomas Crean, Robert Johnston, Larry Bulger, Jim Sealy, Andrew Clinch, Arthur Meares and Cecil Boyd. Magee played in only fourteen of the 21 arranged games of the tour, but played in four Test games against the South African national team. In the First Test he was partnered at half back with Matthew Mullineux, but for the final three tests he was joined by Cambridge University player Sydney Pyman Bell.1899 Home Nations Championship

On his return to Britain, Magee retained his position in the Ireland national team, and from his first game in 1895 he played at centre for 26 consecutive games taking in eight Championship seasons. Magee's finest season was the 1899 Home Nations Championship, which saw him gain the captaincy of the national team in the opening game of the campaign, a home match against England. Ireland won 6–0, with Magee scoring with a penalty kick and long term Irish half back partner, Gerald Allen, scoring a try. Magee then set up two of the tries in a 9–3 victory of Scotland, leaving the encounter with Wales as the decider for the Triple Crown. The game was played at Cardiff Arms Park in front of a record crowd of 40,000, who constantly disrupted the game as the spectators spilled onto the pitch.The game was decided by a single try by Ireland's Gerry Doran, but Magee was called into action preventing a try from one of the Welsh three-quarters in the last minute with a tackle from behind.The win gave Ireland the Triple Crown for the second time in the country's history.1900–1904

Magee continued to captain his country over the next two seasons, but he did not experience the same success as in the 1899 campaign. A single draw against Scotland was the best result in 1900, and apart from a good win over England in 1901 and a strong three-quarters, there was little to celebrate in the Irish results. The 1902 Championship saw Magee lose the captaincy to half back John Fulton. Ireland lost their opening match against England, but after a win over Scotland, Magee was handed the captain's position for the final encounter, against Wales. Ireland were well-beaten in their biggest home defeat since the start of the Championship competition. The 1903 Championship started with a strong win over England, but the Irish captaincy was now in the hands of Harry Corley, Magee's half back partner since the start of 1902. Magee was seen as one of the finest half backs to come out of Ireland, his playing style was of a basic left-side, right-side tradition of half back play; Corley was one of the first specialised fly-halves, pointing the new way forward in rugby play. Ireland failed to capitalise on their strong opening game, losing narrowly to Scotland and then being completely out-classed by Wales. losing 18–0. Magee was dropped for the 1904 Home Nations Championship, replaced by Robinson and Kennedy, as Corley was moved to the centre position. But the team were well beaten by both England and then Scotland, leading the Irish selectors to make eight changes in the final match at home to Wales. Magee was recalled to partner Kennedy in his final international, and the game turned out to be the match of the season. The Welsh took an early lead, but after Ireland were reduced to 14 men through an injury, the team appeared inspired and improved their game. With four tries from each side, the only difference was that Ireland managed to convert one of their tries, whereas Wales missed all theirs. Magee finished his international career with a great win, and with 27 appearances was the most capped Irish player to date. -

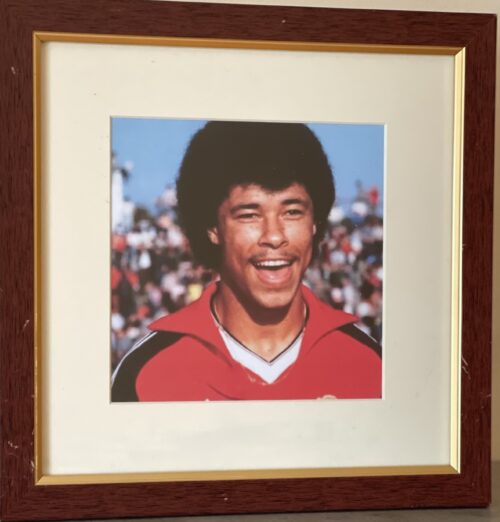

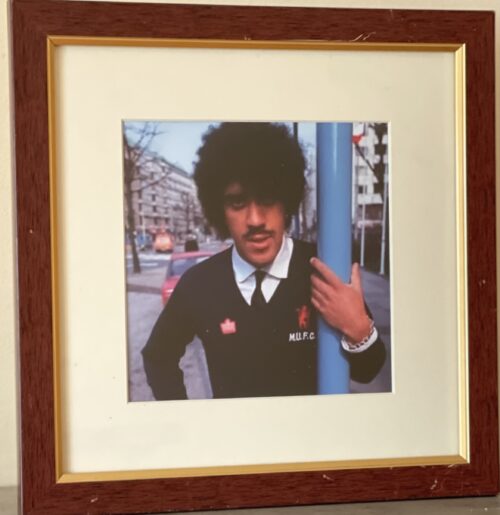

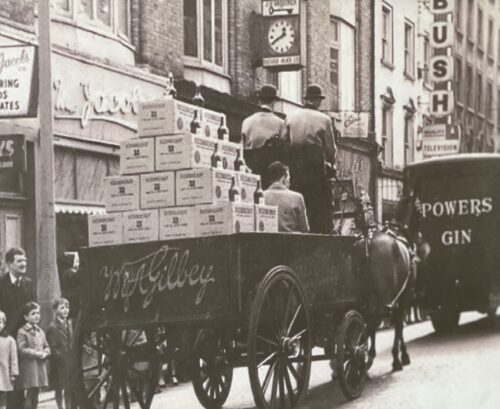

30cm x 30cm

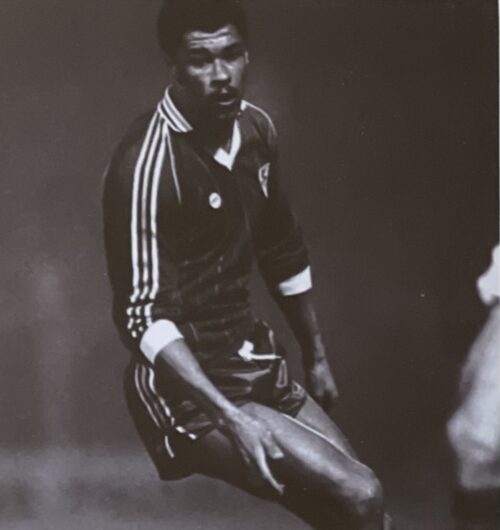

30cm x 30cmPaul McGrath - The Black Pearl of Inchicore

Paul McGrath is one of the greatest footballers to ever play for the Republic of Ireland soccer team. The fact that he managed to perform so well for so long for his clubs and country is all the more remarkable because he was beset by ongoing injury problems and off-pitch issues. McGrath suffered many injuries to his knees over his career and the effects of his alcoholism caused him to miss matches for football club and country on occasions.

McGrath was a natural and magnificent athlete with outstanding soccer talent. His preferred position on the football pitch was at centre-half however the Irish soccer manager Jack Charlton, often deployed him with great success in midfield. From an Irish perspective two of his greatest performances for the Republic of Ireland soccer team were both against Italy and both at World Cup finals. His performance in Rome in 1990 and particularly in New York in 1994 are the stuff of Irish football legend.

Paul McGrath - Early Days

Paul McGrath was born in London in 1959. His mother, Betty, was Irish and the father that he never met was Nigerian. They were not married and in those unenlightened days such a union would have been very much frowned upon. Raising a mixed race baby as an unmarried mother in Ireland in those days just wasn't on so for most people so McGrath's mother headed for London. Shortly after Paul was born his mother came home to Dublin and put her baby up for adoption. McGrath was raised in orphanages and foster homes in Dublin.

As a boy Paul McGrath's love was soccer. It was his means of self-expression and in ways it was a form of escape. His natural talent was apparent from an early age. He played his schoolboy soccer for Pearse Rovers and later he played junior football for Dalkey United.

McGrath - the Professional Footballer

St Patrick's Athletic

In 1981 Paul McGrath became a professional soccer player when he signed for St Patrick's Athletic in Inchicore, Dublin. It was during his short football career with St Pat's that his performances on the pitch were so good that he was dubbed 'The Black Pearl of Inchicore'. McGrath's physique, presence and pure football talent made him stand out on any football pitch that he graced and it wasn't very long before the Irish scouts of English football clubs came calling.

Manchester United

After just one season with St Pat's Paul McGrath's left Ireland in 1982 to begin his English soccer career with Manchester United having been spotted by United's talent scout Billy Behan. At the time United were managed by Ron Atkinson and the team played with a smile on their faces and in a somewhat cavalier fashion. Atkinson was a larger than life character and McGrath took to him immediately. After some initial difficulty in adjusting to the demands of the United training routine Paul settled down to the life of a professional footballer in Manchester. He was helped by the fact that there were other Irish soccer players at the club such as Frank Stapleton, Kevin Moran and Ashley Grimes.

His debut was in the 1982/83 season in a charity match against Aldershot. His league debut was against Tottenham Hotspur in November 1982. Paul went on to make 163 appearances, scoring 12 goals and winning an FA cup medal in 1985 with United. If McGrath felt he had a good relationship with Ron Atkinson, it was clear from early that the Alex Ferguson - Paul McGrath relationship would be not be a comfortable one. Ferguson is renowned as a disciplinarian and McGrath's drinking problems would not allow him to conform to the new stricter regime. Eventually the time came for Paul to find new soccer pastures.

Aston Villa

Paul McGrath transferred Aston Villa in 1989. He was an instant success and the Villa fans embraced him and his sublime footballing skills. Ultimately he was known as 'God' by the fans such was the esteem in which they held him. In the early 1990's Aston Villa were a soccer force in the old Division One (now Premier League) and McGrath was instrumental in the club's push to win the league. Villa were runners-up in 1990 and again 1993. Paul McGrath's performances on the soccer pitch were such that he was voted the PFA Players' Player of the Year in 1993. This was an amazing feat by Paul since "He was, quite literally, a walking wreck" as noted by author Colm Keene in his book: Ireland's Soccer Top 20.

McGrath gained a measure of revenge over Alex Ferguson and Manchester United in 1994 when he helped Aston Villa to beat them at Wembley in the League Cup final. Paul played 252 times for Villa scoring 9 goals in the process.

Derby County & Sheffield United

In 1996 Paul McGrath finished his Villa career by joining Derby County for whom he played 24 times. His final club was Sheffield United but he only managed 11 appearances as his knees could no longer take the punishment. He retired from soccer in 1998.

International Career

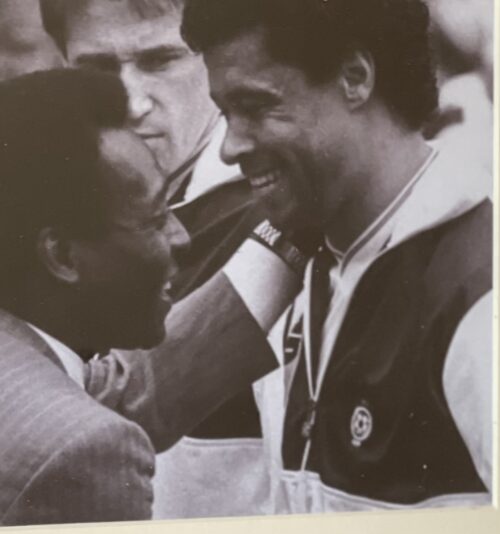

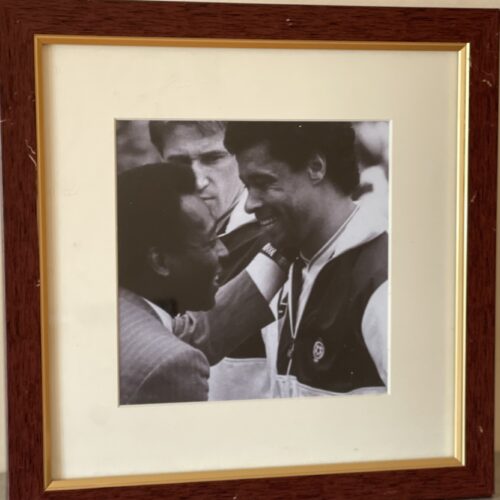

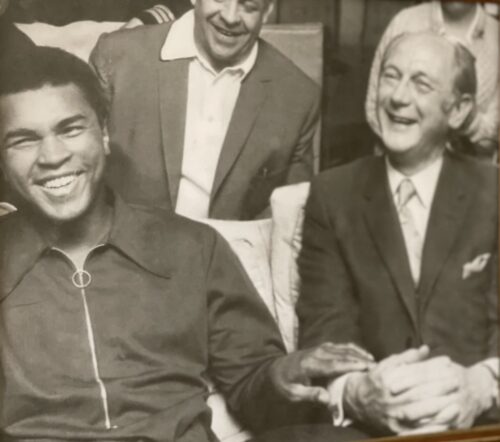

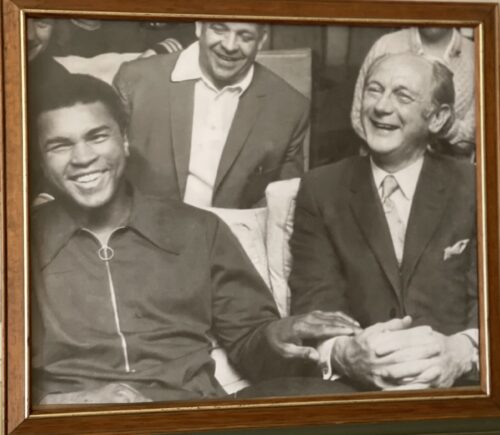

Typical of Paul McGrath

Ireland V Latvia - 1993

Typical of Paul McGrath

Ireland V Latvia - 1993In Dublin Paul McGrath made his international debut for the Republic of Ireland international soccer team in 1985 in a friendly against Italy. The Italians would later be the opponents for two major highs in his international career. He subsequently featured in two of Ireland's three matches in the Euro '88 football finals in Germany.

While his preferred position was centre-half he was competing with the likes of Mark Lawrenson, David O'Leary, Kevin Moran and Mick McCarthy for a berth in the defence. When Jack Charlton took over as the Ireland soccer manager he recognised that with those players he did not need McGrath in defence but he also recognised that McGrath was too good to leave out of the team. Charlton's solution was to play Paul in midfield. He was certainly good enough and he repaid his manager's faith in spades.

Paul McGrath represented his country 83 times on the football pitch scoring eight goals. It is difficult to recall a single poor performance by Paul when playing soccer for Ireland. Even when playing out of his normal position on the pitch invariably he was one of the star performers match-in match-out. Two stand-out performances spring to mind when Irish soccer fans are asked about Paul's greatest matches for Ireland. Both were against Italy. In the quarter final of the 1990 World Cup in Rome Italy were overwhelming favourites to win the match. In a very good overall team performance McGrath's performance stood out as the Irish lost narrowly 1-0.

Great as that performance was, and it really was great, Paul gave an absolute master class four years later in the opening group match in the World Cup finals in New York. Back in his favourite position at centre-half McGrath was simply magnificent. Ireland lead from early through a Ray Houghton goal. The Irish defence had to endure some periods of sustained attack from the talented Italians.

Time and again McGrath repelled Italian attacks, snuffing out danger early, making last ditch tackles, and making towering clearing headers. His performance had it all including one cameo where he made a number tackles in quick succession finally taking a shot full in the face. Unbelievably he was back on his feet in a flash ready to stop whatever else the Italian attack could throw at him.

During Paul McGrath's international career Jack Charlton acted very much as a father figure to Paul and there seems to have been a genuine warmth between them. Like Ferguson, Jack Charlton cuts quite a strict authority figure yet when it came to handling Paul, particularly when it came to dealing with his drinking problems, Charlton dealt with him sensitively and compassionately.

Paul McGrath's Knees & Need for Alcohol

There is no doubt that Paul McGrath had the ability and soccer talent to become one of the true greats of World soccer. One really has to about wonder what he could have achieved if he hadn't been plagued by injuries and if he hadn't been afflicted by alcoholism.

McGrath had never been injured while playing soccer in Ireland yet in the last game in his first season in England he was injured in a bad tackle. This resulted in the need for surgery and it was to be far from the last time he would need to go under the knife. Thus began the Irish nation's obsession with Paul McGrath's knees.

Paul had been getting a bit frustrated at not being able to secure a permanent first team place. Gordon McQueen and Kevin Moran, both experienced and talented players, had the two centre-half positions nailed down. The first injury of his career compounded his frustration and so to escape his negative feelings he resorted to alcohol.

On his recovery from the injury McGrath threw himself into his training, pushing himself harder than ever. Paul now believes that the "hard" training sessions employed by United contributed significantly to his knee problems. The injuries continued to interrupt his progress and it seemed that almost every injury required surgery. Allied to that, McGrath had signed up to then existent United drinking culture. His particular partner in crime was Norman Whiteside who was also injury-prone. Eventually Alex Ferguson concluded that something had to change and the manager decided that Paul McGrath would be transferred from Manchester United. Paul's drinking and his successive injuries effectively ended his career with the biggest soccer club in England.

The rest of his football career was occasionally blighted by the effects of his alcoholism causing to miss training and matches. He later admitted were that there times that he was still under the influence when playing soccer matches.

Over the years Paul had to undergo surgery on eight occasions on his knees. In the final few years of his career McGrath employed a personalised training program that was designed to reduce the impact on his knee joints. Close to the end of his Aston Villa career McGrath could not train at all. He relied upon the football matches to keep up his fitness levels. All the while he was playing with a significant level of pain so much so that he could not even warm up properly for matches

Retirement from Soccer and Back in Ireland

As a footballer, Paul McGrath, is sadly missed by his fans. His autobiography reveals just how heroic this giant of Irish football is - although it makes for harrowing reading at times. McGrath had to contend with problems that would have broken most other men yet this legend had an outstanding football career and produced unforgettable sporting highlights for an adoring public.

In one of his last matches, in a man of the match performance, McGrath inspired Derby County to a shock defeat of Manchester United at Old Trafford. Ferguson said after the match "You have to wonder what a player McGrath should have been." He also commented that "Paul had similar problems to George Best [but] he was without doubt the most natural athlete in football you could imagine". True praise from a football legend who knows a thing or two about football talent.

Truly Paul McGrath is an Irish soccer great now living in County Wexford, Ireland.

To see what others thought about this Irish football legend click on Paul McGrath quotes.

Paul McGrath - Manchester United & Ireland Statistics

Paul McGrath was born on 4th December 1959 in LondonPlaying Position DefenderJoined Manchester United 1982Manchester United Debut 13 November 1982 V Tottenham HotspurLeft Manchester United 1989No. of Games Played for Utd 199Goals scored for Man Utd 16Honours Won by Paul McGrath FA Cup 1985Other Clubs St Patricks Athletic, Aston Villa, Derby County, Sheffield UnitedRepublic of Ireland Caps 83Goals scored for Ireland 8References :

-

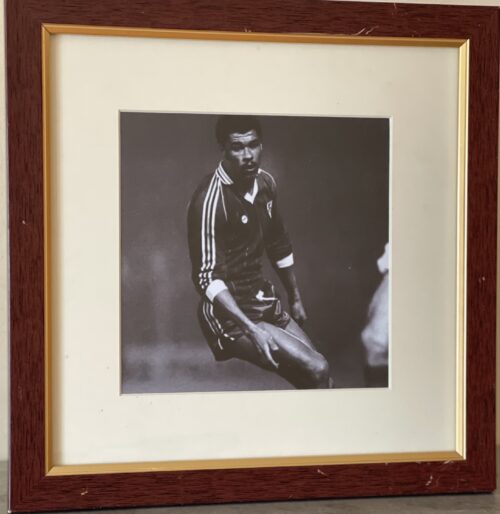

30cm x 30cm

30cm x 30cmPaul McGrath - The Black Pearl of Inchicore

Paul McGrath is one of the greatest footballers to ever play for the Republic of Ireland soccer team. The fact that he managed to perform so well for so long for his clubs and country is all the more remarkable because he was beset by ongoing injury problems and off-pitch issues. McGrath suffered many injuries to his knees over his career and the effects of his alcoholism caused him to miss matches for football club and country on occasions.

McGrath was a natural and magnificent athlete with outstanding soccer talent. His preferred position on the football pitch was at centre-half however the Irish soccer manager Jack Charlton, often deployed him with great success in midfield. From an Irish perspective two of his greatest performances for the Republic of Ireland soccer team were both against Italy and both at World Cup finals. His performance in Rome in 1990 and particularly in New York in 1994 are the stuff of Irish football legend.

Paul McGrath - Early Days

Paul McGrath was born in London in 1959. His mother, Betty, was Irish and the father that he never met was Nigerian. They were not married and in those unenlightened days such a union would have been very much frowned upon. Raising a mixed race baby as an unmarried mother in Ireland in those days just wasn't on so for most people so McGrath's mother headed for London. Shortly after Paul was born his mother came home to Dublin and put her baby up for adoption. McGrath was raised in orphanages and foster homes in Dublin.

As a boy Paul McGrath's love was soccer. It was his means of self-expression and in ways it was a form of escape. His natural talent was apparent from an early age. He played his schoolboy soccer for Pearse Rovers and later he played junior football for Dalkey United.

McGrath - the Professional Footballer

St Patrick's Athletic

In 1981 Paul McGrath became a professional soccer player when he signed for St Patrick's Athletic in Inchicore, Dublin. It was during his short football career with St Pat's that his performances on the pitch were so good that he was dubbed 'The Black Pearl of Inchicore'. McGrath's physique, presence and pure football talent made him stand out on any football pitch that he graced and it wasn't very long before the Irish scouts of English football clubs came calling.

Manchester United

After just one season with St Pat's Paul McGrath's left Ireland in 1982 to begin his English soccer career with Manchester United having been spotted by United's talent scout Billy Behan. At the time United were managed by Ron Atkinson and the team played with a smile on their faces and in a somewhat cavalier fashion. Atkinson was a larger than life character and McGrath took to him immediately. After some initial difficulty in adjusting to the demands of the United training routine Paul settled down to the life of a professional footballer in Manchester. He was helped by the fact that there were other Irish soccer players at the club such as Frank Stapleton, Kevin Moran and Ashley Grimes.

His debut was in the 1982/83 season in a charity match against Aldershot. His league debut was against Tottenham Hotspur in November 1982. Paul went on to make 163 appearances, scoring 12 goals and winning an FA cup medal in 1985 with United. If McGrath felt he had a good relationship with Ron Atkinson, it was clear from early that the Alex Ferguson - Paul McGrath relationship would be not be a comfortable one. Ferguson is renowned as a disciplinarian and McGrath's drinking problems would not allow him to conform to the new stricter regime. Eventually the time came for Paul to find new soccer pastures.

Aston Villa

Paul McGrath transferred Aston Villa in 1989. He was an instant success and the Villa fans embraced him and his sublime footballing skills. Ultimately he was known as 'God' by the fans such was the esteem in which they held him. In the early 1990's Aston Villa were a soccer force in the old Division One (now Premier League) and McGrath was instrumental in the club's push to win the league. Villa were runners-up in 1990 and again 1993. Paul McGrath's performances on the soccer pitch were such that he was voted the PFA Players' Player of the Year in 1993. This was an amazing feat by Paul since "He was, quite literally, a walking wreck" as noted by author Colm Keene in his book: Ireland's Soccer Top 20.

McGrath gained a measure of revenge over Alex Ferguson and Manchester United in 1994 when he helped Aston Villa to beat them at Wembley in the League Cup final. Paul played 252 times for Villa scoring 9 goals in the process.

Derby County & Sheffield United

In 1996 Paul McGrath finished his Villa career by joining Derby County for whom he played 24 times. His final club was Sheffield United but he only managed 11 appearances as his knees could no longer take the punishment. He retired from soccer in 1998.

International Career

Typical of Paul McGrath

Ireland V Latvia - 1993

Typical of Paul McGrath

Ireland V Latvia - 1993In Dublin Paul McGrath made his international debut for the Republic of Ireland international soccer team in 1985 in a friendly against Italy. The Italians would later be the opponents for two major highs in his international career. He subsequently featured in two of Ireland's three matches in the Euro '88 football finals in Germany.

While his preferred position was centre-half he was competing with the likes of Mark Lawrenson, David O'Leary, Kevin Moran and Mick McCarthy for a berth in the defence. When Jack Charlton took over as the Ireland soccer manager he recognised that with those players he did not need McGrath in defence but he also recognised that McGrath was too good to leave out of the team. Charlton's solution was to play Paul in midfield. He was certainly good enough and he repaid his manager's faith in spades.

Paul McGrath represented his country 83 times on the football pitch scoring eight goals. It is difficult to recall a single poor performance by Paul when playing soccer for Ireland. Even when playing out of his normal position on the pitch invariably he was one of the star performers match-in match-out. Two stand-out performances spring to mind when Irish soccer fans are asked about Paul's greatest matches for Ireland. Both were against Italy. In the quarter final of the 1990 World Cup in Rome Italy were overwhelming favourites to win the match. In a very good overall team performance McGrath's performance stood out as the Irish lost narrowly 1-0.

Great as that performance was, and it really was great, Paul gave an absolute master class four years later in the opening group match in the World Cup finals in New York. Back in his favourite position at centre-half McGrath was simply magnificent. Ireland lead from early through a Ray Houghton goal. The Irish defence had to endure some periods of sustained attack from the talented Italians.

Time and again McGrath repelled Italian attacks, snuffing out danger early, making last ditch tackles, and making towering clearing headers. His performance had it all including one cameo where he made a number tackles in quick succession finally taking a shot full in the face. Unbelievably he was back on his feet in a flash ready to stop whatever else the Italian attack could throw at him.

During Paul McGrath's international career Jack Charlton acted very much as a father figure to Paul and there seems to have been a genuine warmth between them. Like Ferguson, Jack Charlton cuts quite a strict authority figure yet when it came to handling Paul, particularly when it came to dealing with his drinking problems, Charlton dealt with him sensitively and compassionately.

Paul McGrath's Knees & Need for Alcohol

There is no doubt that Paul McGrath had the ability and soccer talent to become one of the true greats of World soccer. One really has to about wonder what he could have achieved if he hadn't been plagued by injuries and if he hadn't been afflicted by alcoholism.

McGrath had never been injured while playing soccer in Ireland yet in the last game in his first season in England he was injured in a bad tackle. This resulted in the need for surgery and it was to be far from the last time he would need to go under the knife. Thus began the Irish nation's obsession with Paul McGrath's knees.

Paul had been getting a bit frustrated at not being able to secure a permanent first team place. Gordon McQueen and Kevin Moran, both experienced and talented players, had the two centre-half positions nailed down. The first injury of his career compounded his frustration and so to escape his negative feelings he resorted to alcohol.

On his recovery from the injury McGrath threw himself into his training, pushing himself harder than ever. Paul now believes that the "hard" training sessions employed by United contributed significantly to his knee problems. The injuries continued to interrupt his progress and it seemed that almost every injury required surgery. Allied to that, McGrath had signed up to then existent United drinking culture. His particular partner in crime was Norman Whiteside who was also injury-prone. Eventually Alex Ferguson concluded that something had to change and the manager decided that Paul McGrath would be transferred from Manchester United. Paul's drinking and his successive injuries effectively ended his career with the biggest soccer club in England.

The rest of his football career was occasionally blighted by the effects of his alcoholism causing to miss training and matches. He later admitted were that there times that he was still under the influence when playing soccer matches.

Over the years Paul had to undergo surgery on eight occasions on his knees. In the final few years of his career McGrath employed a personalised training program that was designed to reduce the impact on his knee joints. Close to the end of his Aston Villa career McGrath could not train at all. He relied upon the football matches to keep up his fitness levels. All the while he was playing with a significant level of pain so much so that he could not even warm up properly for matches

Retirement from Soccer and Back in Ireland

As a footballer, Paul McGrath, is sadly missed by his fans. His autobiography reveals just how heroic this giant of Irish football is - although it makes for harrowing reading at times. McGrath had to contend with problems that would have broken most other men yet this legend had an outstanding football career and produced unforgettable sporting highlights for an adoring public.

In one of his last matches, in a man of the match performance, McGrath inspired Derby County to a shock defeat of Manchester United at Old Trafford. Ferguson said after the match "You have to wonder what a player McGrath should have been." He also commented that "Paul had similar problems to George Best [but] he was without doubt the most natural athlete in football you could imagine". True praise from a football legend who knows a thing or two about football talent.

Truly Paul McGrath is an Irish soccer great now living in County Wexford, Ireland.

To see what others thought about this Irish football legend click on Paul McGrath quotes.

Paul McGrath - Manchester United & Ireland Statistics

Paul McGrath was born on 4th December 1959 in LondonPlaying Position DefenderJoined Manchester United 1982Manchester United Debut 13 November 1982 V Tottenham HotspurLeft Manchester United 1989No. of Games Played for Utd 199Goals scored for Man Utd 16Honours Won by Paul McGrath FA Cup 1985Other Clubs St Patricks Athletic, Aston Villa, Derby County, Sheffield UnitedRepublic of Ireland Caps 83Goals scored for Ireland 8References :

-

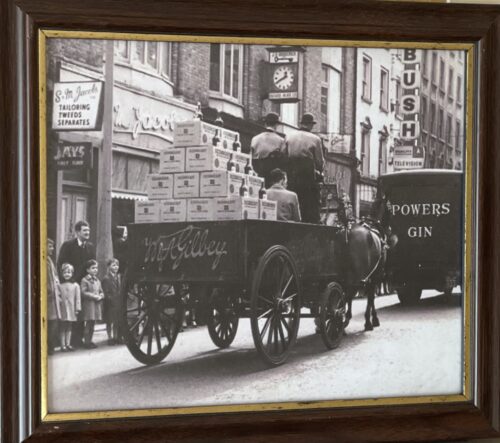

30cm x 30cm

30cm x 30cmPaul McGrath - The Black Pearl of Inchicore

Paul McGrath is one of the greatest footballers to ever play for the Republic of Ireland soccer team. The fact that he managed to perform so well for so long for his clubs and country is all the more remarkable because he was beset by ongoing injury problems and off-pitch issues. McGrath suffered many injuries to his knees over his career and the effects of his alcoholism caused him to miss matches for football club and country on occasions.

McGrath was a natural and magnificent athlete with outstanding soccer talent. His preferred position on the football pitch was at centre-half however the Irish soccer manager Jack Charlton, often deployed him with great success in midfield. From an Irish perspective two of his greatest performances for the Republic of Ireland soccer team were both against Italy and both at World Cup finals. His performance in Rome in 1990 and particularly in New York in 1994 are the stuff of Irish football legend.

Paul McGrath - Early Days

Paul McGrath was born in London in 1959. His mother, Betty, was Irish and the father that he never met was Nigerian. They were not married and in those unenlightened days such a union would have been very much frowned upon. Raising a mixed race baby as an unmarried mother in Ireland in those days just wasn't on so for most people so McGrath's mother headed for London. Shortly after Paul was born his mother came home to Dublin and put her baby up for adoption. McGrath was raised in orphanages and foster homes in Dublin.

As a boy Paul McGrath's love was soccer. It was his means of self-expression and in ways it was a form of escape. His natural talent was apparent from an early age. He played his schoolboy soccer for Pearse Rovers and later he played junior football for Dalkey United.

McGrath - the Professional Footballer

St Patrick's Athletic

In 1981 Paul McGrath became a professional soccer player when he signed for St Patrick's Athletic in Inchicore, Dublin. It was during his short football career with St Pat's that his performances on the pitch were so good that he was dubbed 'The Black Pearl of Inchicore'. McGrath's physique, presence and pure football talent made him stand out on any football pitch that he graced and it wasn't very long before the Irish scouts of English football clubs came calling.

Manchester United

After just one season with St Pat's Paul McGrath's left Ireland in 1982 to begin his English soccer career with Manchester United having been spotted by United's talent scout Billy Behan. At the time United were managed by Ron Atkinson and the team played with a smile on their faces and in a somewhat cavalier fashion. Atkinson was a larger than life character and McGrath took to him immediately. After some initial difficulty in adjusting to the demands of the United training routine Paul settled down to the life of a professional footballer in Manchester. He was helped by the fact that there were other Irish soccer players at the club such as Frank Stapleton, Kevin Moran and Ashley Grimes.

His debut was in the 1982/83 season in a charity match against Aldershot. His league debut was against Tottenham Hotspur in November 1982. Paul went on to make 163 appearances, scoring 12 goals and winning an FA cup medal in 1985 with United. If McGrath felt he had a good relationship with Ron Atkinson, it was clear from early that the Alex Ferguson - Paul McGrath relationship would be not be a comfortable one. Ferguson is renowned as a disciplinarian and McGrath's drinking problems would not allow him to conform to the new stricter regime. Eventually the time came for Paul to find new soccer pastures.

Aston Villa

Paul McGrath transferred Aston Villa in 1989. He was an instant success and the Villa fans embraced him and his sublime footballing skills. Ultimately he was known as 'God' by the fans such was the esteem in which they held him. In the early 1990's Aston Villa were a soccer force in the old Division One (now Premier League) and McGrath was instrumental in the club's push to win the league. Villa were runners-up in 1990 and again 1993. Paul McGrath's performances on the soccer pitch were such that he was voted the PFA Players' Player of the Year in 1993. This was an amazing feat by Paul since "He was, quite literally, a walking wreck" as noted by author Colm Keene in his book: Ireland's Soccer Top 20.

McGrath gained a measure of revenge over Alex Ferguson and Manchester United in 1994 when he helped Aston Villa to beat them at Wembley in the League Cup final. Paul played 252 times for Villa scoring 9 goals in the process.

Derby County & Sheffield United

In 1996 Paul McGrath finished his Villa career by joining Derby County for whom he played 24 times. His final club was Sheffield United but he only managed 11 appearances as his knees could no longer take the punishment. He retired from soccer in 1998.

International Career

Typical of Paul McGrath

Ireland V Latvia - 1993

Typical of Paul McGrath

Ireland V Latvia - 1993In Dublin Paul McGrath made his international debut for the Republic of Ireland international soccer team in 1985 in a friendly against Italy. The Italians would later be the opponents for two major highs in his international career. He subsequently featured in two of Ireland's three matches in the Euro '88 football finals in Germany.

While his preferred position was centre-half he was competing with the likes of Mark Lawrenson, David O'Leary, Kevin Moran and Mick McCarthy for a berth in the defence. When Jack Charlton took over as the Ireland soccer manager he recognised that with those players he did not need McGrath in defence but he also recognised that McGrath was too good to leave out of the team. Charlton's solution was to play Paul in midfield. He was certainly good enough and he repaid his manager's faith in spades.

Paul McGrath represented his country 83 times on the football pitch scoring eight goals. It is difficult to recall a single poor performance by Paul when playing soccer for Ireland. Even when playing out of his normal position on the pitch invariably he was one of the star performers match-in match-out. Two stand-out performances spring to mind when Irish soccer fans are asked about Paul's greatest matches for Ireland. Both were against Italy. In the quarter final of the 1990 World Cup in Rome Italy were overwhelming favourites to win the match. In a very good overall team performance McGrath's performance stood out as the Irish lost narrowly 1-0.

Great as that performance was, and it really was great, Paul gave an absolute master class four years later in the opening group match in the World Cup finals in New York. Back in his favourite position at centre-half McGrath was simply magnificent. Ireland lead from early through a Ray Houghton goal. The Irish defence had to endure some periods of sustained attack from the talented Italians.

Time and again McGrath repelled Italian attacks, snuffing out danger early, making last ditch tackles, and making towering clearing headers. His performance had it all including one cameo where he made a number tackles in quick succession finally taking a shot full in the face. Unbelievably he was back on his feet in a flash ready to stop whatever else the Italian attack could throw at him.

During Paul McGrath's international career Jack Charlton acted very much as a father figure to Paul and there seems to have been a genuine warmth between them. Like Ferguson, Jack Charlton cuts quite a strict authority figure yet when it came to handling Paul, particularly when it came to dealing with his drinking problems, Charlton dealt with him sensitively and compassionately.

Paul McGrath's Knees & Need for Alcohol

There is no doubt that Paul McGrath had the ability and soccer talent to become one of the true greats of World soccer. One really has to about wonder what he could have achieved if he hadn't been plagued by injuries and if he hadn't been afflicted by alcoholism.

McGrath had never been injured while playing soccer in Ireland yet in the last game in his first season in England he was injured in a bad tackle. This resulted in the need for surgery and it was to be far from the last time he would need to go under the knife. Thus began the Irish nation's obsession with Paul McGrath's knees.

Paul had been getting a bit frustrated at not being able to secure a permanent first team place. Gordon McQueen and Kevin Moran, both experienced and talented players, had the two centre-half positions nailed down. The first injury of his career compounded his frustration and so to escape his negative feelings he resorted to alcohol.

On his recovery from the injury McGrath threw himself into his training, pushing himself harder than ever. Paul now believes that the "hard" training sessions employed by United contributed significantly to his knee problems. The injuries continued to interrupt his progress and it seemed that almost every injury required surgery. Allied to that, McGrath had signed up to then existent United drinking culture. His particular partner in crime was Norman Whiteside who was also injury-prone. Eventually Alex Ferguson concluded that something had to change and the manager decided that Paul McGrath would be transferred from Manchester United. Paul's drinking and his successive injuries effectively ended his career with the biggest soccer club in England.

The rest of his football career was occasionally blighted by the effects of his alcoholism causing to miss training and matches. He later admitted were that there times that he was still under the influence when playing soccer matches.

Over the years Paul had to undergo surgery on eight occasions on his knees. In the final few years of his career McGrath employed a personalised training program that was designed to reduce the impact on his knee joints. Close to the end of his Aston Villa career McGrath could not train at all. He relied upon the football matches to keep up his fitness levels. All the while he was playing with a significant level of pain so much so that he could not even warm up properly for matches

Retirement from Soccer and Back in Ireland

As a footballer, Paul McGrath, is sadly missed by his fans. His autobiography reveals just how heroic this giant of Irish football is - although it makes for harrowing reading at times. McGrath had to contend with problems that would have broken most other men yet this legend had an outstanding football career and produced unforgettable sporting highlights for an adoring public.

In one of his last matches, in a man of the match performance, McGrath inspired Derby County to a shock defeat of Manchester United at Old Trafford. Ferguson said after the match "You have to wonder what a player McGrath should have been." He also commented that "Paul had similar problems to George Best [but] he was without doubt the most natural athlete in football you could imagine". True praise from a football legend who knows a thing or two about football talent.

Truly Paul McGrath is an Irish soccer great now living in County Wexford, Ireland.

To see what others thought about this Irish football legend click on Paul McGrath quotes.

Paul McGrath - Manchester United & Ireland Statistics

Paul McGrath was born on 4th December 1959 in LondonPlaying Position DefenderJoined Manchester United 1982Manchester United Debut 13 November 1982 V Tottenham HotspurLeft Manchester United 1989No. of Games Played for Utd 199Goals scored for Man Utd 16Honours Won by Paul McGrath FA Cup 1985Other Clubs St Patricks Athletic, Aston Villa, Derby County, Sheffield UnitedRepublic of Ireland Caps 83Goals scored for Ireland 8References :

-

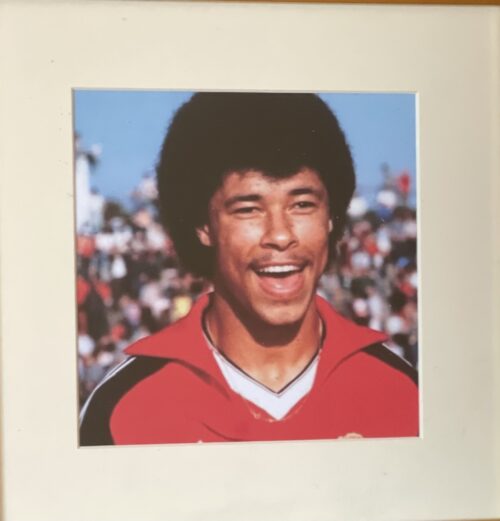

30cm x 30cm

30cm x 30cmPaul McGrath - The Black Pearl of Inchicore

Paul McGrath is one of the greatest footballers to ever play for the Republic of Ireland soccer team. The fact that he managed to perform so well for so long for his clubs and country is all the more remarkable because he was beset by ongoing injury problems and off-pitch issues. McGrath suffered many injuries to his knees over his career and the effects of his alcoholism caused him to miss matches for football club and country on occasions.

McGrath was a natural and magnificent athlete with outstanding soccer talent. His preferred position on the football pitch was at centre-half however the Irish soccer manager Jack Charlton, often deployed him with great success in midfield. From an Irish perspective two of his greatest performances for the Republic of Ireland soccer team were both against Italy and both at World Cup finals. His performance in Rome in 1990 and particularly in New York in 1994 are the stuff of Irish football legend.

Paul McGrath - Early Days

Paul McGrath was born in London in 1959. His mother, Betty, was Irish and the father that he never met was Nigerian. They were not married and in those unenlightened days such a union would have been very much frowned upon. Raising a mixed race baby as an unmarried mother in Ireland in those days just wasn't on so for most people so McGrath's mother headed for London. Shortly after Paul was born his mother came home to Dublin and put her baby up for adoption. McGrath was raised in orphanages and foster homes in Dublin.

As a boy Paul McGrath's love was soccer. It was his means of self-expression and in ways it was a form of escape. His natural talent was apparent from an early age. He played his schoolboy soccer for Pearse Rovers and later he played junior football for Dalkey United.

McGrath - the Professional Footballer

St Patrick's Athletic

In 1981 Paul McGrath became a professional soccer player when he signed for St Patrick's Athletic in Inchicore, Dublin. It was during his short football career with St Pat's that his performances on the pitch were so good that he was dubbed 'The Black Pearl of Inchicore'. McGrath's physique, presence and pure football talent made him stand out on any football pitch that he graced and it wasn't very long before the Irish scouts of English football clubs came calling.

Manchester United

After just one season with St Pat's Paul McGrath's left Ireland in 1982 to begin his English soccer career with Manchester United having been spotted by United's talent scout Billy Behan. At the time United were managed by Ron Atkinson and the team played with a smile on their faces and in a somewhat cavalier fashion. Atkinson was a larger than life character and McGrath took to him immediately. After some initial difficulty in adjusting to the demands of the United training routine Paul settled down to the life of a professional footballer in Manchester. He was helped by the fact that there were other Irish soccer players at the club such as Frank Stapleton, Kevin Moran and Ashley Grimes.

His debut was in the 1982/83 season in a charity match against Aldershot. His league debut was against Tottenham Hotspur in November 1982. Paul went on to make 163 appearances, scoring 12 goals and winning an FA cup medal in 1985 with United. If McGrath felt he had a good relationship with Ron Atkinson, it was clear from early that the Alex Ferguson - Paul McGrath relationship would be not be a comfortable one. Ferguson is renowned as a disciplinarian and McGrath's drinking problems would not allow him to conform to the new stricter regime. Eventually the time came for Paul to find new soccer pastures.

Aston Villa

Paul McGrath transferred Aston Villa in 1989. He was an instant success and the Villa fans embraced him and his sublime footballing skills. Ultimately he was known as 'God' by the fans such was the esteem in which they held him. In the early 1990's Aston Villa were a soccer force in the old Division One (now Premier League) and McGrath was instrumental in the club's push to win the league. Villa were runners-up in 1990 and again 1993. Paul McGrath's performances on the soccer pitch were such that he was voted the PFA Players' Player of the Year in 1993. This was an amazing feat by Paul since "He was, quite literally, a walking wreck" as noted by author Colm Keene in his book: Ireland's Soccer Top 20.

McGrath gained a measure of revenge over Alex Ferguson and Manchester United in 1994 when he helped Aston Villa to beat them at Wembley in the League Cup final. Paul played 252 times for Villa scoring 9 goals in the process.

Derby County & Sheffield United

In 1996 Paul McGrath finished his Villa career by joining Derby County for whom he played 24 times. His final club was Sheffield United but he only managed 11 appearances as his knees could no longer take the punishment. He retired from soccer in 1998.

International Career

Typical of Paul McGrath

Ireland V Latvia - 1993

Typical of Paul McGrath