HOLDING OF THE THIN GREEN LINE – UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN BOAT CLUB & THE 1948 OLYMPIC GAMES

BY MORGAN MCELLIGOTT

“Telegram for you, Professor.” The year was 1948 in Mooney’s of the Strand. Jim read “Flight delayed, cannot make Mooney’s, see you at Henley- on – Thames signed Holly.” Apparently the barman was transferred from the Dublin premises near Independent House to London and recognised his erstwhile customer, Jim Meenan. “Holly” was a sobriquet for J.J.E. Holloway, representative of the Leinster branch of the Irish Amateur Rowing Union (I.A.R.U.) and to the Federation Internationale des Societes d’Aviron (F.I.S.A.). The former was secretary and later President of the union. Both were officers of Old Collegians Boat Club (O.C.B.C.) and members of the emergency committee to deal with the Irish Olympic eight-oar crew entry and were hugely involved with the development of U.C.D. rowing. The Club founded in 1918, assumed significance in the thirties and peaked in 1939 by winning the intervarsity Wylie Cup and the Irish Senior and Junior Rowing Championships, coached by Holly and captained by Dermot Pierce, brother of Denis Sugrue.1947-1948

After some lean years, the College aimed at revivification under the author’s captaincy, by intensive training twice daily in 1947, repeating the above wins and making a significant inaugural appearance at the Royal Henley Regatta by beating Reading University and Kings College London in the initial rounds in the Thames Cup before elimination in the semi-final by the eventual winners, Kent School U.S.A. It was easy to predict the outcome of the 1948 season which, captained by Paddy Dooley, repeated the above Irish competitive season, finishing by victory in the final of the Irish Senior Eights Championship over Belfast Commercial Boat Club, at present Belfast Rowing Club, on the river Lagan.

CREW SELECTED

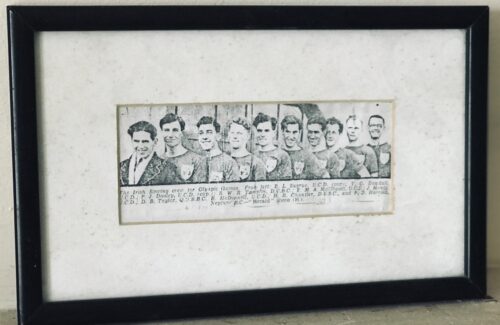

The I.A.R.U. had ruled previously that the winning eight would be nominated as an All- Ireland entry to the Olympic Games and the relevant sub-committee met immediately after the race on the 10th July 1948 and U.C.D. were invited to form the Olympic Crew. Dominant advice was given and accepted fully from Ray Hickey, who rowed in the successful Senior Championship eight in 1940 and coached both 1947 and 1948 crews. Initial practice was on the 12th and the crew was finally selected on the 16th July as follows:-|

Bow |

T.G. Dowdall |

UCD |

|

2

|

E.M.A McElligott |

UCD |

|

3

|

J. Hanly |

UCD |

|

4

|

D.D.B. Taylor |

Queen’s |

|

5

|

B. McDonnell |

UCD |

|

6

|

P.D.R. Harold |

Neptune |

|

7

|

R.W.R Tamplin |

Trinity |

|

Stroke

|

P.O. Dooley |

UCD |

|

Cox

|

D.L. Sugrue |

UCD |

|

Coaches |

R.G. Hickey |

UCD |

|

M. Horan |

Trinity |

|

|

Manager |

D.S.F. O’Leary |

UCD |

|

Substitutes |

H.R. Chantler |

Trinity |

|

W. Stevens |

Neptune |

EIRE/IRELAND-26/32

So far it seemed simple, but now it was the Eire/Ireland question; briefly, “Eire” meant pick your athletes from twenty-six counties, whereas “Ireland”‘ meant thirty-two counties. Dan Taylor, Captain of the Q.U.B.C. was included and the I.A.R.U. was not yet a member of the F.I.S.A. Some seventeen days of training followed on both Liffey and Thames. Long mileage was the hallmark of the college crews in the previous two seasons and included an indelibly remembered row from Islandbridge to Poolbeg Lighthouse on a calm day, it was subsequently learned that the U.S.A. and Norway, gold and bronze medal winners, crewed for two years and nine months respectively.BORDERLINE CONSEQUENCES

But more important matters were imminent in Henley-on-Thames Town Hall, such as, “Can we row Danny from Queens, Belfast? ” John Pius Boland, of Boland’s Bread and a law graduate of Balliol College Oxford, was a commissioner under the Irish Universities Act and named the new establishment the National University of Ireland. Earlier, in 1896, after winning two gold medals for tennis in the first Olympic Games of the modern era, he caused some upset when he demanded an Irish flag. Subsequent to the establishment of the twenty-six country Irish Free State, the question of Olympic entry from a thirty-two county Ireland was debated and re-affirmed at four international Olympic committee meetings ranging from Paris in 1924 to Berlin in 1930. In 1932, Bob Tisdall, 400 meters hurdle and Pat O’Callaghan, hammer, won gold medals; the thirty-two county status was thought to be ensured in spite of persistent objections by British, representatives, which were constantly over-ruled until 1934. In context, Sean Lavan of U.C.D. achieved first and second places in various heats of 200 and 400 meters in 1924 and 1928.ORATIO RECTA 1948 dialectic included: –

BOADICEA: Conqueror of Italians: “Eire is on your stamps and on your Department of External Affairs note paper.” MACHA: war Goddess of Ulster: “Yes, and you have Helvetia on your stamps and Switzerland on your note paper.” BOADICEA: “Eirelevant! And note the spelling, if you’ve graduated from Ogham. Your swimmers are already barred because of the inclusion of Northern Ireland competitors.” MACHA: “A jarvey’s arrogance, why, you have four competitors, born in southern Ireland including Chris Barton from Kildare, who stroked the British eight, winning a silver medal. Being rather proud of our athletic exports, we never raised the issue.” BOADICEA: “Verdant remarks from a verdant person, and how about Danny Boy from Queen’s University Boat Club.” MACHA: “Well, he is entitled to British and Irish passports and that reminds me of your performance of an Irish melody, the Londonderry Air which concerns my fief. BOADICEA: “Your Kevin Myers states you cannot be “Ireland” without a referendum.” MACHA: “Anachronisms are unacceptable and on your next raid on Londinium ask the king’s equerry why he introduced my friends as “Ireland” at the Buckingham Palace tea-party”.

FAULTY TOWERS

The twin towers of Wembley stadium came into view, we were going on parade with increased confidence in our entry, while the swimmers returned to Eire/Ireland. As we took our place, it appeared that the parade sign-board was Eire rather than Ireland. A rather polemic discussion ensued between the assistant Chief Marshal and Comdt. J.F. Chisholm, the Irish Chef de Mission; the latter pointed out that our entry was submitted and accepted as “Ireland” as the English language was mandatory in context e.g. Espana marched as Spain. The Marshal’s convincing riposte was that he always wrote “Eire” when writing to his Irish brother-in-law and that P. agus T. delivered accurately; this was followed by an awesome threat to trap us in the tunnel.

CORK’S CREWMANSHIP

The ebullient Donal S.F. O Leary, who rowed in the successful 1947 Wylie Cup senior eight, with Alphie Walshe, and, at present, our team manager assessed instantly the situation and when we were directed to march in line after Iraq, declared forcibly that there were thousands of Irish, or was it Eirish, people in the stands ready to cheer their team and wouldn’t it be an huge disappointment if we failed to march, on a matter of neology.

ON STREAM

In a temperature 90 F, with 58 nations, we marched as “Eire,” saluted King GeorgeVl, were cheered loudly by our own and by countries like India which recently gained independence, as we worried about losing a day’s practice on the water. The words of the visionary Pierre Baron de Coubertin, who revived the Olympic Games in 1896 after a lapse of some 1600 years, dominated the stadium:

THE IMPORTANT THING IN THE OLYMPIC GAMES IS NOT WINNING BUT TAKING PART. THE ESSENTIAL THING IN LIFE IS NOT CONQUERING BUT FIGHTING WELL

The Olympic torch, carried through a peaceful Europe, arrived and the Olympic flame was lit by Cambridge athlete, John Mark. Donald Finlay, former Olympic hurdler swore the oath. The King proclaimed the games open, Sir Malcolm Sergent, of the Albert Hall promenade concerts, conducted the orchestra with guards massed bands and choir in a stirring performance of the Londonderry Air; thousands of pigeons were released to carry messages of peace to countries of the world.But upstream to Henley, the thirty-two county body I.A.R.U., represented by its President M.V. Rowan of Neptune R.C. and J.J.E. Holloway O.C.B.C., was elected unanimously to F.I.S.A. and was therefore the first athletic unit recognised as an all Ireland body at the XIV Olympiad. A laudable photo-finish as competition started on the morrow and it’s worth mentioning that, in contrast to current debatable practice, Irish rowing officials disclaimed all expenses.

LADIES LAST AND FIRST

A liberal proposal by eastern European countries “on the organisation of feminine championships received scant attention”. An Antipodean delegate stated that in his opinion: “Rowing, as a sport had sufficient complications without adding the feminine element thereto”. In a recent season Antipodean values, not delegates, prevailed in U.C.D. Ladies Boat Club captained by Oonagh Clarke; wins of their Senior Eight included Ghent International Regatta and Henley Regatta, beating Temple University U.S.A. in the final – a glorious season for the “feminine element”.THIN GREEN LINE

During all this induction, practice continued on the water. Most of the crew thought pragmatically that as long as we rowed all else was irrelevant. Heart or head, to be conservative at twenty is to have no heart, to be socialist at forty is to have no head. Initially some of our training was alongside the British crew, whom we could beat transiently off the starting stake-boat; the objection of other crews ended this liaison. Our exercise times over parts of the course proved favourably and superior to some of our competitors but on the day we were beaten in our heat by Canada and Portugal and the repechage by Norway. To quote Michael Johnston in his totally comprehensive book on Senior Championship rowing, entitled “The Big Pot”:- “They lost their races but held the Thin Green Line and brought Ireland into the world of real international rowing for the first time. “MEMORIA

Joe Hanly and Barry McDonnell were both heavy weights on the 1947 and 1948 championship crews, and subsequently Presidents of O.C.B.C. Joe was also Vice-Captain of U.C.D.B.C. in 1947. Barry died in 1976 and Joe in 1996. The sympathy of all U.C.D. Oarsmen was extended to their wives, Helen who was Inaugural President of U.C.D.B.C. Ladies, and Jane, respectively. In 1997 Joe was honoured posthumously in the presence of Jane and Dr. Art Cosgrove, President U.C.D., by naming a new fine VIII boat, “Joe Hanly” in the presence of Barry Doyle, President U.C.D.B.C. RESURRECTI SUMUSIn 1998 the 1948 Olympic crew were honoured in the presence of some 170 crews competing in the Irish National Rowing Championships. Inscribed trophies and pennants were presented by Tom Fennessy, President of the I.A.R.U. and Michael Johnston, in his citation, stressed how the crew ensured thirty-two county representation by holding the Thin Green Line.

Similarly, twenty-five contestants, out of a total ninety-one who competed in 1948, attended a reception hosted by the Irish Olympic Council. Trophies were presented and citations declared by Patrick Hickey. President of the Council. Speeches included that of Dave Guiney, National Irish Shop-Putting Champion, who spoke for the recipients, and Dr. Kevin O’Flanagan who received a special presentation for his medical services to the Games. During his student days at U.C.D. in the 1940’s, O’Flanagan developed a career which included winning National Championships for Sprinting, playing International Soccer and Rugby for Ireland.

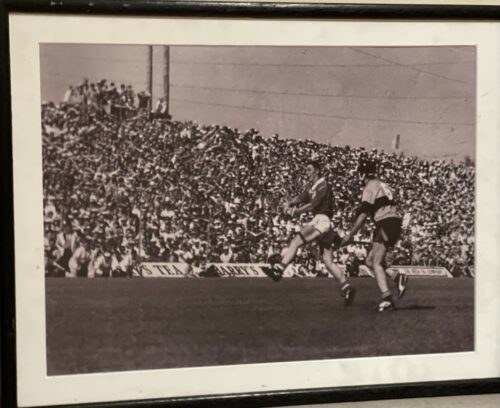

Many years on, Stuart Wilson vividly recalled the Dennison tackles and spoke about them in remarkable detail and with commendable honesty: “The move involved me coming in from the blind side wing and it had been working very well on tour. It was a workable move and it was paying off so we just kept rolling it out. Against Munster, the gap opened up brilliantly as it was supposed to except that there was this little guy called Seamus Dennison sitting there in front of me.

“He just basically smacked the living daylights out of me. I dusted myself off and thought, I don’t want to have to do that again. Ten minutes later, we called the same move again thinking we’d change it slightly but, no, it didn’t work and I got hammered again.”

The game was 11 minutes old when the most famous try in the history of Munster rugby was scored.

Tom Kiernan recalled: “It came from a great piece of anticipation by Bowen who in the first place had to run around his man to get to Ward’s kick ahead. He then beat two men and when finally tackled, managed to keep his balance and deliver the ball to Cantillon who went on to score. All of this was evidence of sharpness on Bowen’s part.”

Very soon it would be 9-0. In the first five minutes, a towering garryowen by skipper Canniffe had exposed the vulnerability of the New Zealand rearguard under the high ball. They were to be examined once or twice more but it was from a long range but badly struck penalty attempt by Ward that full-back Brian McKechnie knocked on some 15 yards from his line and close to where Cantillon had touched down a few minutes earlier. You could sense White, Whelan, McLoughlin and co in the front five of the Munster scrum smacking their lips as they settled for the scrum. A quick, straight put-in by Canniffe, a well controlled heel, a smart pass by the scrum-half to Ward and the inevitability of a drop goal. And that’s exactly what happened.

The All Blacks enjoyed the majority of forward possession but the harder they tried, the more they fell into the trap set by the wily Kiernan and so brilliantly carried out by every member of the Munster team.

The tourists might have edged the line-out contest through Andy Haden and Frank Oliver but scrum-half Mark Donaldson endured a miserable afternoon as the Munster forwards poured through and buried him in the Thomond Park turf.

As the minutes passed and the All Blacks became more and more unsure as to what to try next, the Thomond Park hordes chanted “Munster-Munster–Munster” to an ever increasing crescendo until with 12 minutes to go, the noise levels reached deafening proportions.

And then ... a deep, probing kick by Ward put Wilson under further pressure. Eventually, he stumbled over the ball as it crossed the line and nervously conceded a five-metre scrum. The Munster heel was disrupted but the ruck was won, Tucker gained possession and slipped a lovely little pass to Ward whose gifted feet and speed of thought enabled him in a twinkle to drop a goal although surrounded by a swarm of black jerseys. So the game entered its final 10 minutes with the All Blacks needing three scores to win and, of course, that was never going to happen.

Munster knew this, so, too, did the All Blacks. Stu Wilson admitted as much as he explained his part in Wardy’s second drop goal: “Tony Ward banged it down, it bounced a little bit, jigged here, jigged there, and I stumbled, fell over, and all of a sudden the heat was on me. They were good chasers. A kick is a kick — but if you have lots of good chasers on it, they make bad kicks look good. I looked up and realised — I’m not going to run out of here so I just dotted it down. I wasn’t going to run that ball back out at them because five of those mad guys were coming down the track at me and I’m thinking, I’m being hit by these guys all day and I’m looking after my body, thank you. Of course it was a five-yard scrum and Ward banged over another drop goal. That was it, there was the game”.

The final whistle duly sounded with Munster 12 points ahead but the heroes of the hour still had to get off the field and reach the safety of the dressing room. Bodies were embraced, faces were kissed, backs were pummelled, you name it, the gauntlet had to be walked. Even the All Blacks seemed impressed with the sense of joy being released all about them. Andy Haden recalled “the sea of red supporters all over the pitch after the game, you could hardly get off for the wave of celebration that was going on. The whole of Thomond Park glowed in the warmth that someone had put one over on the Blacks.”

Controversially, the All Blacks coach, Jack Gleeson (usually a man capable of accepting the good with the bad and who passed away of cancer within 12 months of the tour), in an unguarded (although possibly misunderstood) moment on the following day, let slip his innermost thoughts on the game.

“We were up against a team of kamikaze tacklers,” he lamented. “We set out on this tour to play 15-man rugby but if teams were to adopt the Munster approach and do all they could to stop the All Blacks from playing an attacking game, then the tour and the game would suffer.”

It was interpreted by the majority of observers as a rare piece of sour grapes from a group who had accepted the defeat in good spirit and it certainly did nothing to diminish Munster respect for the All Blacks and their proud rugby tradition.

Many years on, Stuart Wilson vividly recalled the Dennison tackles and spoke about them in remarkable detail and with commendable honesty: “The move involved me coming in from the blind side wing and it had been working very well on tour. It was a workable move and it was paying off so we just kept rolling it out. Against Munster, the gap opened up brilliantly as it was supposed to except that there was this little guy called Seamus Dennison sitting there in front of me.

“He just basically smacked the living daylights out of me. I dusted myself off and thought, I don’t want to have to do that again. Ten minutes later, we called the same move again thinking we’d change it slightly but, no, it didn’t work and I got hammered again.”

The game was 11 minutes old when the most famous try in the history of Munster rugby was scored.

Tom Kiernan recalled: “It came from a great piece of anticipation by Bowen who in the first place had to run around his man to get to Ward’s kick ahead. He then beat two men and when finally tackled, managed to keep his balance and deliver the ball to Cantillon who went on to score. All of this was evidence of sharpness on Bowen’s part.”

Very soon it would be 9-0. In the first five minutes, a towering garryowen by skipper Canniffe had exposed the vulnerability of the New Zealand rearguard under the high ball. They were to be examined once or twice more but it was from a long range but badly struck penalty attempt by Ward that full-back Brian McKechnie knocked on some 15 yards from his line and close to where Cantillon had touched down a few minutes earlier. You could sense White, Whelan, McLoughlin and co in the front five of the Munster scrum smacking their lips as they settled for the scrum. A quick, straight put-in by Canniffe, a well controlled heel, a smart pass by the scrum-half to Ward and the inevitability of a drop goal. And that’s exactly what happened.

The All Blacks enjoyed the majority of forward possession but the harder they tried, the more they fell into the trap set by the wily Kiernan and so brilliantly carried out by every member of the Munster team.

The tourists might have edged the line-out contest through Andy Haden and Frank Oliver but scrum-half Mark Donaldson endured a miserable afternoon as the Munster forwards poured through and buried him in the Thomond Park turf.

As the minutes passed and the All Blacks became more and more unsure as to what to try next, the Thomond Park hordes chanted “Munster-Munster–Munster” to an ever increasing crescendo until with 12 minutes to go, the noise levels reached deafening proportions.

And then ... a deep, probing kick by Ward put Wilson under further pressure. Eventually, he stumbled over the ball as it crossed the line and nervously conceded a five-metre scrum. The Munster heel was disrupted but the ruck was won, Tucker gained possession and slipped a lovely little pass to Ward whose gifted feet and speed of thought enabled him in a twinkle to drop a goal although surrounded by a swarm of black jerseys. So the game entered its final 10 minutes with the All Blacks needing three scores to win and, of course, that was never going to happen.

Munster knew this, so, too, did the All Blacks. Stu Wilson admitted as much as he explained his part in Wardy’s second drop goal: “Tony Ward banged it down, it bounced a little bit, jigged here, jigged there, and I stumbled, fell over, and all of a sudden the heat was on me. They were good chasers. A kick is a kick — but if you have lots of good chasers on it, they make bad kicks look good. I looked up and realised — I’m not going to run out of here so I just dotted it down. I wasn’t going to run that ball back out at them because five of those mad guys were coming down the track at me and I’m thinking, I’m being hit by these guys all day and I’m looking after my body, thank you. Of course it was a five-yard scrum and Ward banged over another drop goal. That was it, there was the game”.

The final whistle duly sounded with Munster 12 points ahead but the heroes of the hour still had to get off the field and reach the safety of the dressing room. Bodies were embraced, faces were kissed, backs were pummelled, you name it, the gauntlet had to be walked. Even the All Blacks seemed impressed with the sense of joy being released all about them. Andy Haden recalled “the sea of red supporters all over the pitch after the game, you could hardly get off for the wave of celebration that was going on. The whole of Thomond Park glowed in the warmth that someone had put one over on the Blacks.”

Controversially, the All Blacks coach, Jack Gleeson (usually a man capable of accepting the good with the bad and who passed away of cancer within 12 months of the tour), in an unguarded (although possibly misunderstood) moment on the following day, let slip his innermost thoughts on the game.

“We were up against a team of kamikaze tacklers,” he lamented. “We set out on this tour to play 15-man rugby but if teams were to adopt the Munster approach and do all they could to stop the All Blacks from playing an attacking game, then the tour and the game would suffer.”

It was interpreted by the majority of observers as a rare piece of sour grapes from a group who had accepted the defeat in good spirit and it certainly did nothing to diminish Munster respect for the All Blacks and their proud rugby tradition.