-

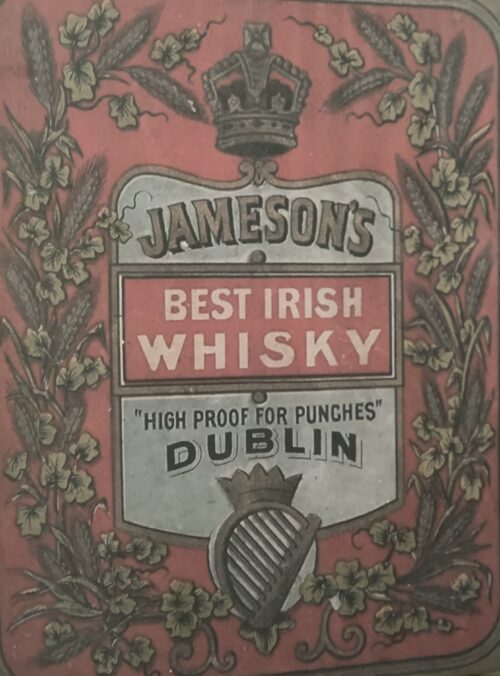

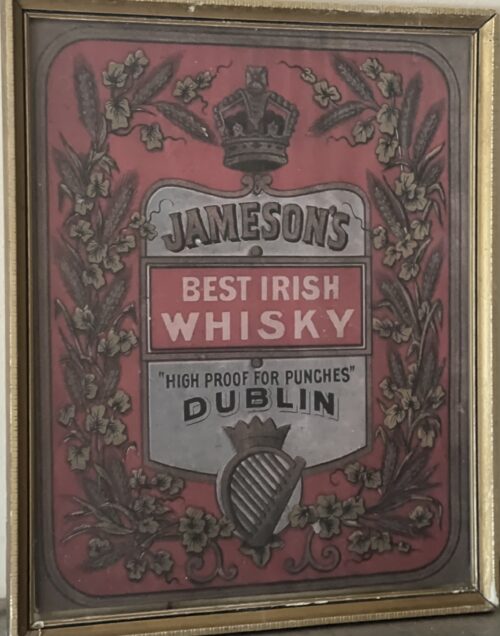

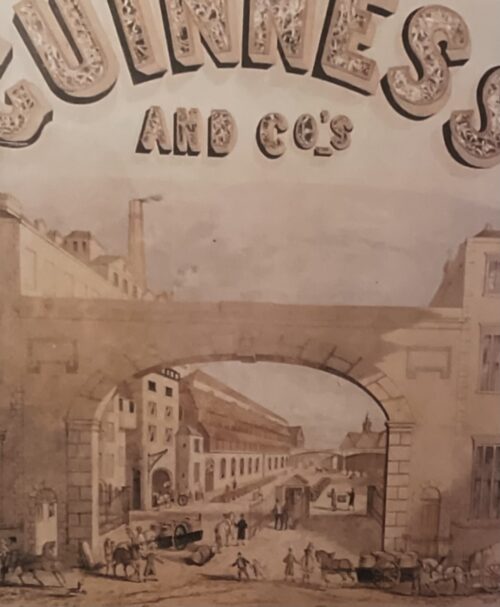

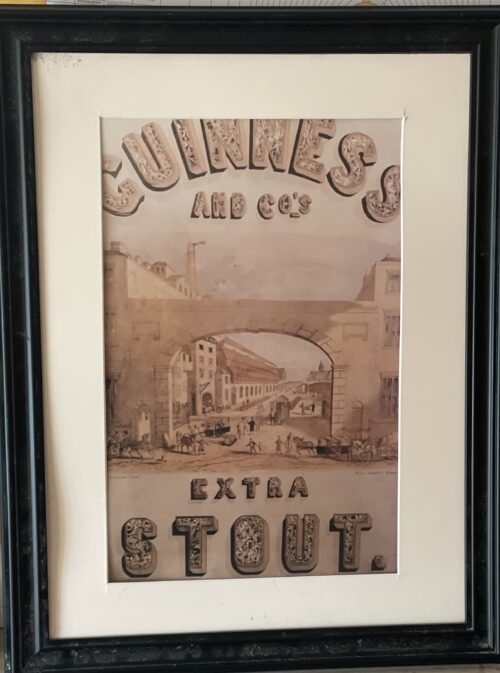

50cm x 40cm Limerick John Jameson was originally a lawyer from Alloa in Scotland before he founded his eponymous distillery in Dublin in 1780.Prevoius to this he had made the wise move of marrying Margaret Haig (1753–1815) in 1768,one of the simple reasons being Margaret was the eldest daughter of John Haig, the famous whisky distiller in Scotland. John and Margaret had eight sons and eight daughters, a family of 16 children. Portraits of the couple by Sir Henry Raeburn are on display in the National Gallery of Ireland. John Jameson joined the Convivial Lodge No. 202, of the Dublin Freemasons on the 24th June 1774 and in 1780, Irish whiskey distillation began at Bow Street. In 1805, he was joined by his son John Jameson II who took over the family business that year and for the next 41 years, John Jameson II built up the business before handing over to his son John Jameson the 3rd in 1851. In 1901, the Company was formally incorporated as John Jameson and Son Ltd. Four of John Jameson’s sons followed his footsteps in distilling in Ireland, John Jameson II (1773 – 1851) at Bow Street, William and James Jameson at Marrowbone Lane in Dublin (where they partnered their Stein relations, calling their business Jameson and Stein, before settling on William Jameson & Co.). The fourth of Jameson's sons, Andrew, who had a small distillery at Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, was the grandfather of Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of wireless telegraphy. Marconi’s mother was Annie Jameson, Andrew’s daughter. John Jameson’s eldest son, Robert took over his father’s legal business in Alloa. The Jamesons became the most important distilling family in Ireland, despite rivalry between the Bow Street and Marrowbone Lane distilleries. By the turn of the 19th century, it was the second largest producer in Ireland and one of the largest in the world, producing 1,000,000 gallons annually. Dublin at the time was the centre of world whiskey production. It was the second most popular spirit in the world after rum and internationally Jameson had by 1805 become the world's number one whiskey. Today, Jameson is the world's third largest single-distillery whiskey. Historical events, for a time, set the company back. The temperance movement in Ireland had an enormous impact domestically but the two key events that affected Jameson were the Irish War of Independence and subsequent trade war with the British which denied Jameson the export markets of the Commonwealth, and shortly thereafter, the introduction of prohibition in the United States. While Scottish brands could easily slip across the Canada–US border, Jameson was excluded from its biggest market for many years. The introduction of column stills by the Scottish blenders in the mid-19th-century enabled increased production that the Irish, still making labour-intensive single pot still whiskey, could not compete with. There was a legal enquiry somewhere in 1908 to deal with the trade definition of whiskey. The Scottish producers won within some jurisdictions, and blends became recognised in the law of that jurisdiction as whiskey. The Irish in general, and Jameson in particular, continued with the traditional pot still production process for many years.In 1966 John Jameson merged with Cork Distillers and John Powers to form the Irish Distillers Group. In 1976, the Dublin whiskey distilleries of Jameson in Bow Street and in John's Lane were closed following the opening of a New Midleton Distillery by Irish Distillers outside Cork. The Midleton Distillery now produces much of the Irish whiskey sold in Ireland under the Jameson, Midleton, Powers, Redbreast, Spot and Paddy labels. The new facility adjoins the Old Midleton Distillery, the original home of the Paddy label, which is now home to the Jameson Experience Visitor Centre and the Irish Whiskey Academy. The Jameson brand was acquired by the French drinks conglomerate Pernod Ricard in 1988, when it bought Irish Distillers. The old Jameson Distillery in Bow Street near Smithfield in Dublin now serves as a museum which offers tours and tastings. The distillery, which is historical in nature and no longer produces whiskey on site, went through a $12.6 million renovation that was concluded in March 2016, and is now a focal part of Ireland's strategy to raise the number of whiskey tourists, which stood at 600,000 in 2017.Bow Street also now has a fully functioning Maturation Warehouse within its walls since the 2016 renovation. It is here that Jameson 18 Bow Street is finished before being bottled at Cask Strength. In 2008, The Local, an Irish pub in Minneapolis, sold 671 cases of Jameson (22 bottles a day),making it the largest server of Jameson's in the world – a title it maintained for four consecutive years.

50cm x 40cm Limerick John Jameson was originally a lawyer from Alloa in Scotland before he founded his eponymous distillery in Dublin in 1780.Prevoius to this he had made the wise move of marrying Margaret Haig (1753–1815) in 1768,one of the simple reasons being Margaret was the eldest daughter of John Haig, the famous whisky distiller in Scotland. John and Margaret had eight sons and eight daughters, a family of 16 children. Portraits of the couple by Sir Henry Raeburn are on display in the National Gallery of Ireland. John Jameson joined the Convivial Lodge No. 202, of the Dublin Freemasons on the 24th June 1774 and in 1780, Irish whiskey distillation began at Bow Street. In 1805, he was joined by his son John Jameson II who took over the family business that year and for the next 41 years, John Jameson II built up the business before handing over to his son John Jameson the 3rd in 1851. In 1901, the Company was formally incorporated as John Jameson and Son Ltd. Four of John Jameson’s sons followed his footsteps in distilling in Ireland, John Jameson II (1773 – 1851) at Bow Street, William and James Jameson at Marrowbone Lane in Dublin (where they partnered their Stein relations, calling their business Jameson and Stein, before settling on William Jameson & Co.). The fourth of Jameson's sons, Andrew, who had a small distillery at Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, was the grandfather of Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of wireless telegraphy. Marconi’s mother was Annie Jameson, Andrew’s daughter. John Jameson’s eldest son, Robert took over his father’s legal business in Alloa. The Jamesons became the most important distilling family in Ireland, despite rivalry between the Bow Street and Marrowbone Lane distilleries. By the turn of the 19th century, it was the second largest producer in Ireland and one of the largest in the world, producing 1,000,000 gallons annually. Dublin at the time was the centre of world whiskey production. It was the second most popular spirit in the world after rum and internationally Jameson had by 1805 become the world's number one whiskey. Today, Jameson is the world's third largest single-distillery whiskey. Historical events, for a time, set the company back. The temperance movement in Ireland had an enormous impact domestically but the two key events that affected Jameson were the Irish War of Independence and subsequent trade war with the British which denied Jameson the export markets of the Commonwealth, and shortly thereafter, the introduction of prohibition in the United States. While Scottish brands could easily slip across the Canada–US border, Jameson was excluded from its biggest market for many years. The introduction of column stills by the Scottish blenders in the mid-19th-century enabled increased production that the Irish, still making labour-intensive single pot still whiskey, could not compete with. There was a legal enquiry somewhere in 1908 to deal with the trade definition of whiskey. The Scottish producers won within some jurisdictions, and blends became recognised in the law of that jurisdiction as whiskey. The Irish in general, and Jameson in particular, continued with the traditional pot still production process for many years.In 1966 John Jameson merged with Cork Distillers and John Powers to form the Irish Distillers Group. In 1976, the Dublin whiskey distilleries of Jameson in Bow Street and in John's Lane were closed following the opening of a New Midleton Distillery by Irish Distillers outside Cork. The Midleton Distillery now produces much of the Irish whiskey sold in Ireland under the Jameson, Midleton, Powers, Redbreast, Spot and Paddy labels. The new facility adjoins the Old Midleton Distillery, the original home of the Paddy label, which is now home to the Jameson Experience Visitor Centre and the Irish Whiskey Academy. The Jameson brand was acquired by the French drinks conglomerate Pernod Ricard in 1988, when it bought Irish Distillers. The old Jameson Distillery in Bow Street near Smithfield in Dublin now serves as a museum which offers tours and tastings. The distillery, which is historical in nature and no longer produces whiskey on site, went through a $12.6 million renovation that was concluded in March 2016, and is now a focal part of Ireland's strategy to raise the number of whiskey tourists, which stood at 600,000 in 2017.Bow Street also now has a fully functioning Maturation Warehouse within its walls since the 2016 renovation. It is here that Jameson 18 Bow Street is finished before being bottled at Cask Strength. In 2008, The Local, an Irish pub in Minneapolis, sold 671 cases of Jameson (22 bottles a day),making it the largest server of Jameson's in the world – a title it maintained for four consecutive years. -

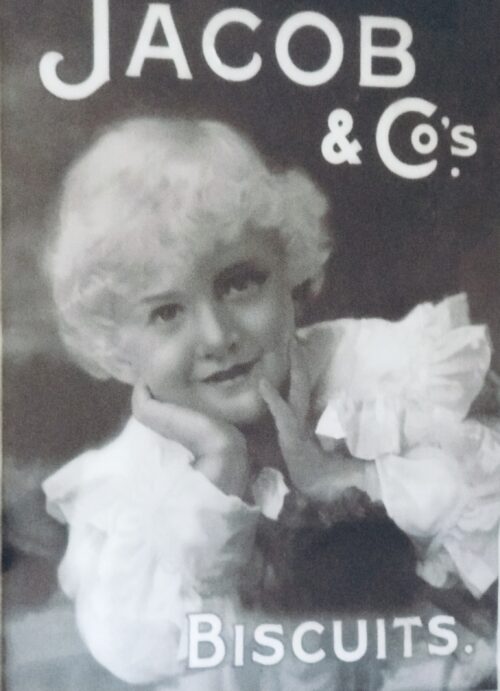

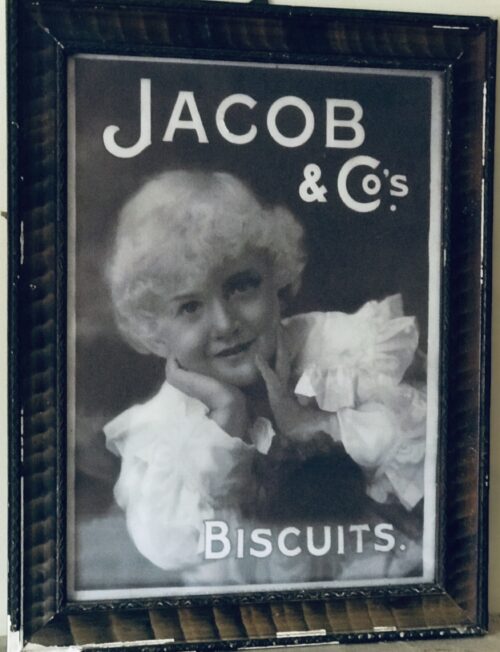

The Jacobs Biscuit Bakery originated in Waterford in 1851,after being founded by William Beale Jacob and his brother Robert.It later moved to Bishop Street in Dublin with a further factory in Peters Row.Jacobs Bishop Street premises was occupied as a strategic location by rebels during the 1916 Easter Rebellion.This charming advert depicting a rather cherubic looking young child dates to the early 1930s. Dublin 57cm x 45cm The biscuit making firm of W. & R. Jacob's were one the largest employers in the Dublin of 1916, and their factory was seized on Easter Monday by perhaps 100 members of the 2nd Battalion of the Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers under Thomas MacDonagh. The factory itself was an enormous and formidable Victorian edifice located on the 'block' enclosed by Bishop St, Bride St, Peter's St and Peter's Row, and between St Patrick's Cathedral and St Stephen's Green. Its seizure helped to complete a loop of building cross the south inner city; the factory had two large towers that could act as observation points, while its location was very close to both Camden St and Patrick St: natural routeways for troops entering the city centre from Portobello Barracks in Rathmines and Wellington Barracks on the South Circular Road. There were only a few staff present in the building when the Volunteers broke into it; a number of smaller outposts were established in the area around the factory. While the garrison saw some fighting early in the week, their principal enemies proved to be boredom and the locals: the factory was surrounded by tenements, and the Volunteers were attacked and abused by residents, many of whom were Jacob's workers themselves. The families of servicemen were also quite hostile, but there may have been another reason for this hostility: Michael O'Hanrahan, who was in Jacob's, expressed his concern that the choice of location might endanger local residents if the British chose to attack. As it happens, the factory was largely by-passed, though it was fired upon intermittently throughout the week by troops in Dublin Castle and elsewhere. MacDonagh surrendered in nearby St Patrick's Park on Sunday 30 April; some of the factory was looted after the Volunteers had left. Three members of the Jacob's garrison were executed. Most of the factory was eventually demolished, though fragments of the ground storey and one of the towers are still visible on Bishop St between the DIT campus on Aungier St and the National Archives of Ireland.

The Jacobs Biscuit Bakery originated in Waterford in 1851,after being founded by William Beale Jacob and his brother Robert.It later moved to Bishop Street in Dublin with a further factory in Peters Row.Jacobs Bishop Street premises was occupied as a strategic location by rebels during the 1916 Easter Rebellion.This charming advert depicting a rather cherubic looking young child dates to the early 1930s. Dublin 57cm x 45cm The biscuit making firm of W. & R. Jacob's were one the largest employers in the Dublin of 1916, and their factory was seized on Easter Monday by perhaps 100 members of the 2nd Battalion of the Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers under Thomas MacDonagh. The factory itself was an enormous and formidable Victorian edifice located on the 'block' enclosed by Bishop St, Bride St, Peter's St and Peter's Row, and between St Patrick's Cathedral and St Stephen's Green. Its seizure helped to complete a loop of building cross the south inner city; the factory had two large towers that could act as observation points, while its location was very close to both Camden St and Patrick St: natural routeways for troops entering the city centre from Portobello Barracks in Rathmines and Wellington Barracks on the South Circular Road. There were only a few staff present in the building when the Volunteers broke into it; a number of smaller outposts were established in the area around the factory. While the garrison saw some fighting early in the week, their principal enemies proved to be boredom and the locals: the factory was surrounded by tenements, and the Volunteers were attacked and abused by residents, many of whom were Jacob's workers themselves. The families of servicemen were also quite hostile, but there may have been another reason for this hostility: Michael O'Hanrahan, who was in Jacob's, expressed his concern that the choice of location might endanger local residents if the British chose to attack. As it happens, the factory was largely by-passed, though it was fired upon intermittently throughout the week by troops in Dublin Castle and elsewhere. MacDonagh surrendered in nearby St Patrick's Park on Sunday 30 April; some of the factory was looted after the Volunteers had left. Three members of the Jacob's garrison were executed. Most of the factory was eventually demolished, though fragments of the ground storey and one of the towers are still visible on Bishop St between the DIT campus on Aungier St and the National Archives of Ireland. -

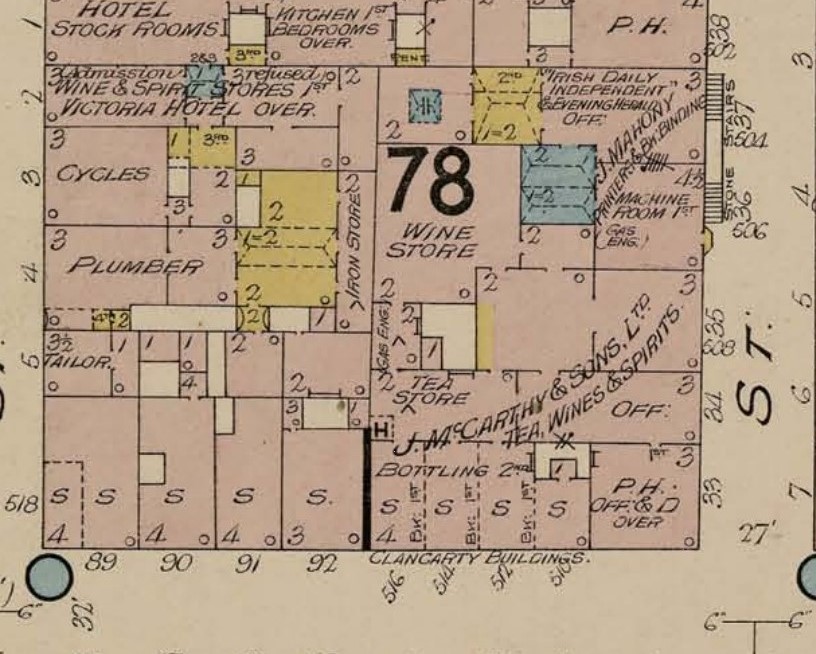

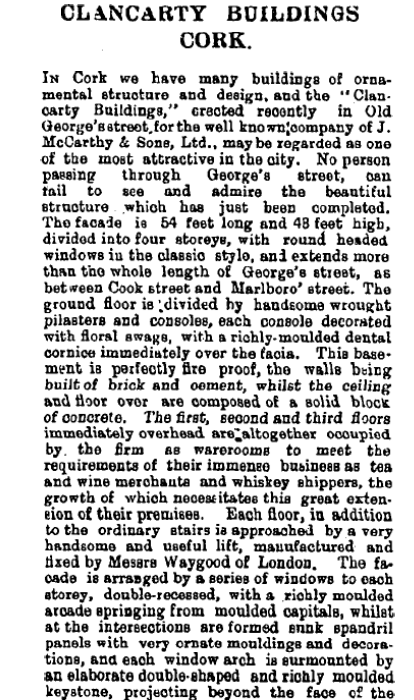

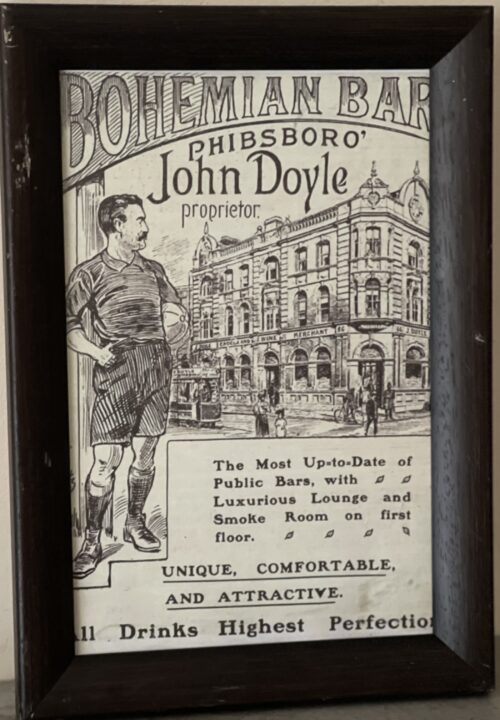

47cm x 37cm Limerick The building itself it is a terraced eight-bay four-storey late-Victorian commercial building, It was built across 1895 and 1896 for J McCarthy and Sons, Wholesale Tea and Wine Merchants. Named the Clancarty (family of Carty) Buildings, the building was designed by architect and built by John Delaney. The Cork Examiner on 10 August 1896 (p.9) describes the impressive building: “No person passing through George’s street, can fail to see and admire the beautiful structure, which has just been completed. The facade is 54 feet long and 48 feet high, divided into four storeys, with round headed windows in the classic style, and extends more than the whole length of George’s Street, as between Cook street and Marlboro Street. The ground floor is divided by handsome wrought pilasters and consoles, each console decorated with floral swags, with a richly-moulded dental cornice immediately over the facia. This basement is perfectly fire proof, the walls being built of brick and cement, whilst the ceiling and floor over are composed of a solid block of concrete. The first, second and third floors immediately overhead are altogether occupied by the firm as warerooms to meet the requirements of their immense business as tea and wine merchants and whiskey shippers, the growth of which necessitates this great extension of their premises”.

47cm x 37cm Limerick The building itself it is a terraced eight-bay four-storey late-Victorian commercial building, It was built across 1895 and 1896 for J McCarthy and Sons, Wholesale Tea and Wine Merchants. Named the Clancarty (family of Carty) Buildings, the building was designed by architect and built by John Delaney. The Cork Examiner on 10 August 1896 (p.9) describes the impressive building: “No person passing through George’s street, can fail to see and admire the beautiful structure, which has just been completed. The facade is 54 feet long and 48 feet high, divided into four storeys, with round headed windows in the classic style, and extends more than the whole length of George’s Street, as between Cook street and Marlboro Street. The ground floor is divided by handsome wrought pilasters and consoles, each console decorated with floral swags, with a richly-moulded dental cornice immediately over the facia. This basement is perfectly fire proof, the walls being built of brick and cement, whilst the ceiling and floor over are composed of a solid block of concrete. The first, second and third floors immediately overhead are altogether occupied by the firm as warerooms to meet the requirements of their immense business as tea and wine merchants and whiskey shippers, the growth of which necessitates this great extension of their premises”.

J McCarthy and Sons, Wholesale Tea and Wine Merchants as shown in Goads Insurance Map of Cork, 1906 (source: Kieran McCarthy)

Description of Clancarty Buildings, Cork Examiner, 10 August 1896, p.9 (source: Cork City Library) -

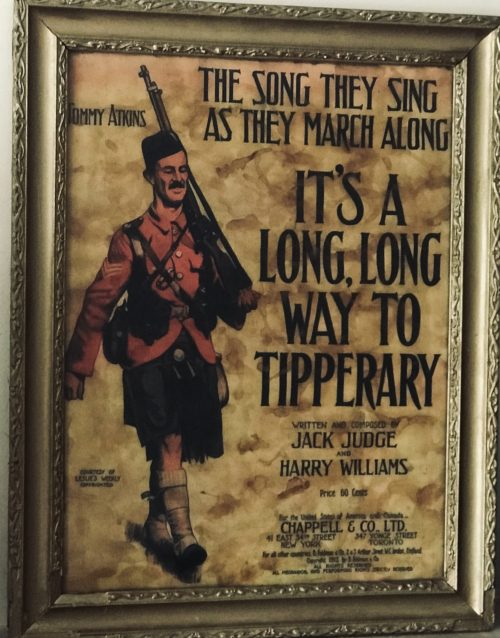

Superb vintage poster advertising the famous WW1 era music hall song of 'Its a long long way to Tipperary". 60cm x 45cm London United Kingdom Long Way to Tipperary" (or "It's a Long, Long Way to Tipperary") is a British music hall song first performed in 1912 by Jack Judge, and written by Judge and Harry Williams though authorship of the song has long been disputed. It was recorded in 1914 by Irish tenor John McCormack. It became popular as a marching song among soldiers in the First World War and is remembered as a song of that war. Welcoming signs in the referenced county of Tipperary, Ireland, humorously declare, "You've come a long long way..." in reference to the song.

Superb vintage poster advertising the famous WW1 era music hall song of 'Its a long long way to Tipperary". 60cm x 45cm London United Kingdom Long Way to Tipperary" (or "It's a Long, Long Way to Tipperary") is a British music hall song first performed in 1912 by Jack Judge, and written by Judge and Harry Williams though authorship of the song has long been disputed. It was recorded in 1914 by Irish tenor John McCormack. It became popular as a marching song among soldiers in the First World War and is remembered as a song of that war. Welcoming signs in the referenced county of Tipperary, Ireland, humorously declare, "You've come a long long way..." in reference to the song.Authorship

Jack Judge's parents were Irish, and his grandparents came from Tipperary. Judge met Harry Williams (Henry James Williams, 23 September 1873 – 21 February 1924) in Oldbury, Worcestershire at the Malt Shovel public house, where Williams's brother Ben was the licensee. Williams was severely disabled, having fallen down cellar steps as a child and badly broken both legs. He had developed a talent for writing verse and songs, and played the piano and mandolin, often in public. Judge and Williams began a long-term writing partnership that resulted in 32 music hall songs published by Bert Feldman. Many of the songs were composed by Williams and Judge at Williams's home, The Plough Inn (later renamed The Tipperary Inn), in Balsall Common. Because Judge could not read or write music, Williams taught them to Judge by ear. Judge was a popular semi-professional performer in music halls. In January 1912, he was performing at the Grand Theatre in Stalybridge, and accepted a 5-shilling bet that he could compose and sing a new song by the next night. The following evening, 31 January, Judge performed "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" for the first time, and it immediately became a great success. The song was originally written and performed as a sentimental ballad, to be enjoyed by Irish expatriates living in London.Judge sold the rights to the song to Bert Feldman in London, who agreed to publish it and other songs written by Judge with Williams. Feldman published the song as "It's a Long, Long Way to Tipperary" in October 1912, and promoted it as a march.Dispute

Feldman paid royalties to both Judge and Williams, but after Williams' death in 1924, Judge claimed sole credit for writing the song, saying that he had agreed to Williams being co-credited as recompense for a debt that Judge owed. However, Williams' family showed that the tune and most of the lyrics to the song already existed in the form of a manuscript, "It's A Long Way to Connemara", co-written by Williams and Judge back in 1909, and Judge had used this, just changing some words, including changing "Connemara" to "Tipperary" Judge said: "I was the sole composer of 'Tipperary', and all other songs published in our names jointly. They were all 95% my work, as Mr Williams made only slight alterations to the work he wrote down from my singing the compositions. He would write it down on music-lined paper and play it back, then I'd work on the music a little more ... I have sworn affidavits in my possession by Bert Feldman, the late Harry Williams and myself confirming that I am the composer ...". In a 1933 interview, he added: "The words and music of the song were written in the Newmarket Tavern, Corporation Street, Stalybridge on 31st January 1912, during my engagement at the Grand Theatre after a bet had been made that a song could not be written and sung the next evening ... Harry was very good to me and used to assist me financially, and I made a promise to him that if I ever wrote a song and published it, I would put his name on the copies and share the proceeds with him. Not only did I generously fulfil that promise, but I placed his name with mine on many more of my own published contributions. During Mr Williams' lifetime (as far as I know) he never claimed to be the writer of the song ...". Williams's family campaigned in 2012 to have Harry Williams officially re-credited with the song, and shared their archives with the Imperial War Museums. The family estate still receives royalties from the song.Other claims

In 1917, Alice Smyth Burton Jay sued song publishers Chappell & Co. for $100,000, alleging she wrote the tune in 1908 for a song played at the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition promoting the Washington apple industry. The chorus began "I'm on my way to Yakima". The court appointed Victor Herbert to act as expert advisor and dismissed the suit in 1920, since the authors of "Tipperary" had never been to Seattle and Victor Herbert testified the two songs were not similar enough to suggest plagiarism.Content

The song was originally written as a lament from an Irish worker in London, missing his homeland, before it became a popular soldiers' marching song. One of the most popular hits of the time, the song is atypical in that it is not a warlike song that incites the soldiers to glorious deeds. Popular songs in previous wars (such as the Boer Wars) frequently did this. In the First World War, however, the most popular songs, like this one and "Keep the Home Fires Burning", concentrated on the longing for home.Reception

Feldman persuaded Florrie Forde to perform the song in 1913, but she disliked it and dropped it from her act. However, it became widely known. During the First World War, Daily Mailcorrespondent George Curnock saw the Irish regiment the Connaught Rangers singing this song as they marched through Boulogne on 13 August 1914, and reported it on 18 August 1914. The song was quickly picked up by other units of the British Army. In November 1914, it was recorded by Irish tenor John McCormack, which helped its worldwide popularity. Other popular versions in the USA in 1915 were by the American Quartet, Prince's Orchestra, and Albert Farrington. The popularity of the song among soldiers, despite (or because of) its irreverent and non-military theme, was noted at the time, and was contrasted with the military and patriotic songs favoured by enemy troops. Commentators considered that the song's appeal revealed characteristically British qualities of being cheerful in the face of hardship. The Times suggested that "'Tipperary' may be less dignified, but it, and whatever else our soldiers may choose to sing will be dignified by their bravery, their gay patience, and their long suffering kindness... We would rather have their deeds than all the German songs in the world."Later performances

Early recording star Billy Murray, with the American Quartet, sang "It's A Long Way To Tipperary" as a straightforward march, complete with brass, drums and cymbals, with a quick bar of "Rule, Britannia!" thrown into the instrumental interlude between the first and second verse-chorus combination. The song was featured as one of the songs in the 1951 film On Moonlight Bay, the 1960s stage musical and film Oh! What a Lovely War and the 1970 musical Darling Lili, sung by Julie Andrews. It was also sung by the prisoners of war in Jean Renoir's film La Grande Illusion (1937) and as background music in The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming (1966). It is also the second part (the other two being Hanging on the Old Barbed Wire and Mademoiselle from Armentières) of the regimental march of Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry. Mystery Science Theater 3000 used it twice, sung by Crow T. Robot in Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie (1996), then sung again for the final television episode. It is also sung by British soldiers in the film The Travelling Players (1975) directed by Theo Angelopoulos, and by Czechoslovak soldiers in the movie Černí baroni (1992). The song is often cited when documentary footage of the First World War is presented. One example of its use is in the annual television special It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown (1966). Snoopy—who fancies himself as a First World War flying ace—dances to a medley of First World War-era songs played by Schroeder. This song is included, and at that point Snoopy falls into a left-right-left marching pace. Schroeder also played this song in Snoopy, Come Home (1972) at Snoopy's send-off party. Also, Snoopy was seen singing the song out loud in a series of strips about his going to the 1968 Winter Olympics. In another strip, Snoopy is walking so long a distance to Tipperary that he lies down exhausted and notes, "They're right, it is a long way to Tipperary." On a different occasion, Snoopy walks along and begins to sing the song, only to meet a sign that reads, "Tipperary: One Block." In a Sunday strip wherein Snoopy, in his World War I fantasy state, walks into Marcie's home, thinking it a French café, and falls asleep after drinking all her root beer, she rousts him awake by loudly singing the song. It is also featured in For Me and My Gal (1942) starring Judy Garland and Gene Kelly and Gallipoli (1981) starring Mel Gibson. The cast of The Mary Tyler Moore Show march off screen singing the song at the conclusion of the series’ final episode, after news anchor Ted Baxter (played by Ted Knight) had inexplicably recited some of the lyrics on that evening's news broadcast. It was sung by the crew of U-96 in Wolfgang Petersen's 1981 film Das Boot (that particular arrangement was performed by the Red Army Choir). Morale is boosted in the submarine when the German crew sings the song as they begin patrolling in the North Atlantic Ocean. The crew sings it a second time as they cruise toward home port after near disaster. When the hellship SS Lisbon Maru was sinking, the Royal Artillery POWS trapped in the vessel are reported to have sung this song. Survivors of the sinking of HMS Tipperary in the Battle of Jutland (1916) were identified by their rescuers on HMS Sparrowhawk because they were singing "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" in their lifeboat. In Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie (1996), based on the popular cable series Mystery Science Theater 3000, robot character Crow T. Robot sings a version of the song while wearing a World War I British Army helmet, and declaring "We must confound Gerry (the Germans) at every turn!"Lyrics

Up to mighty London Came an Irishman one day. As the streets are paved with gold Sure, everyone was gay, Singing songs of Piccadilly, Strand and Leicester Square, Till Paddy got excited, Then he shouted to them there: Chorus It's a long way to Tipperary, It's a long way to go. It's a long way to Tipperary, To the sweetest girl I know! Goodbye, Piccadilly, Farewell, Leicester Square! It's a long long way to Tipperary, But my heart's right there. Paddy wrote a letter To his Irish Molly-O, Saying, "Should you not receive it, Write and let me know!" "If I make mistakes in spelling, Molly, dear," said he, "Remember, it's the pen that's bad, Don't lay the blame on me!" Chorus Molly wrote a neat reply To Irish Paddy-O, Saying "Mike Maloney Wants to marry me, and so Leave the Strand and Piccadilly Or you'll be to blame, For love has fairly drove me silly: Hoping you're the same!" ChorusAn alternative bawdy concluding chorus:That's the wrong way to tickle Mary, That's the wrong way to kiss. Don't you know that over here, lad They like it best like this. Hoo-ray pour les français, Farewell Angleterre. We didn't know how to tickle Mary, But we learnt how over there. -

Charming portrait on a postcard of an old Irish Piper-with the inscription- The Uilleann pipes are the characteristic national bagpipe of Ireland. Earlier known in English as "union pipes", their current name is a partial translation of the Irish-language term píobaí uilleann (literally, "pipes of the elbow"), from their method of inflation. There is no historical record of the name or use of the term uilleann pipes before the twentieth century. It was an invention of Grattan Flood and the name stuck. People mistook the term 'union' to refer to the 1800 Act of Union; this is incorrect as Breandán Breathnach points out that a poem published in 1796 uses the term 'union'. The bag of the uilleann pipes is inflated by means of a small set of bellows strapped around the waist and the right arm (in the case of a right-handed player; in the case of a left-handed player the location and orientation of all components are reversed). The bellows not only relieve the player from the effort needed to blow into a bag to maintain pressure, they also allow relatively dry air to power the reeds, reducing the adverse effects of moisture on tuning and longevity. Some pipers can converse or sing while playing. The uilleann pipes are distinguished from many other forms of bagpipes by their tone and wide range of notes – the chanter has a range of two full octaves, including sharps and flats – together with the unique blend of chanter, drones, and regulators. The regulators are equipped with closed keys that can be opened by the piper's wrist action enabling the piper to play simple chords, giving a rhythmic and harmonic accompaniment as needed. There are also many ornaments based on multiple or single grace notes. The chanter can also be played staccato by resting the bottom of the chanter on the piper's thigh to close off the bottom hole and then open and close only the tone holes required. If one tone hole is closed before the next one is opened, a staccato effect can be created because the sound stops completely when no air can escape at all. The uilleann pipes have a different harmonic structure, sounding sweeter and quieter than many other bagpipes, such as the Great Irish warpipes, Great Highland bagpipes or the Italian zampognas. The uilleann pipes are often played indoors, and are almost always played sitting down Origins :Co Laois Dimensions: 24cm x 20cm

Charming portrait on a postcard of an old Irish Piper-with the inscription- The Uilleann pipes are the characteristic national bagpipe of Ireland. Earlier known in English as "union pipes", their current name is a partial translation of the Irish-language term píobaí uilleann (literally, "pipes of the elbow"), from their method of inflation. There is no historical record of the name or use of the term uilleann pipes before the twentieth century. It was an invention of Grattan Flood and the name stuck. People mistook the term 'union' to refer to the 1800 Act of Union; this is incorrect as Breandán Breathnach points out that a poem published in 1796 uses the term 'union'. The bag of the uilleann pipes is inflated by means of a small set of bellows strapped around the waist and the right arm (in the case of a right-handed player; in the case of a left-handed player the location and orientation of all components are reversed). The bellows not only relieve the player from the effort needed to blow into a bag to maintain pressure, they also allow relatively dry air to power the reeds, reducing the adverse effects of moisture on tuning and longevity. Some pipers can converse or sing while playing. The uilleann pipes are distinguished from many other forms of bagpipes by their tone and wide range of notes – the chanter has a range of two full octaves, including sharps and flats – together with the unique blend of chanter, drones, and regulators. The regulators are equipped with closed keys that can be opened by the piper's wrist action enabling the piper to play simple chords, giving a rhythmic and harmonic accompaniment as needed. There are also many ornaments based on multiple or single grace notes. The chanter can also be played staccato by resting the bottom of the chanter on the piper's thigh to close off the bottom hole and then open and close only the tone holes required. If one tone hole is closed before the next one is opened, a staccato effect can be created because the sound stops completely when no air can escape at all. The uilleann pipes have a different harmonic structure, sounding sweeter and quieter than many other bagpipes, such as the Great Irish warpipes, Great Highland bagpipes or the Italian zampognas. The uilleann pipes are often played indoors, and are almost always played sitting down Origins :Co Laois Dimensions: 24cm x 20cm -

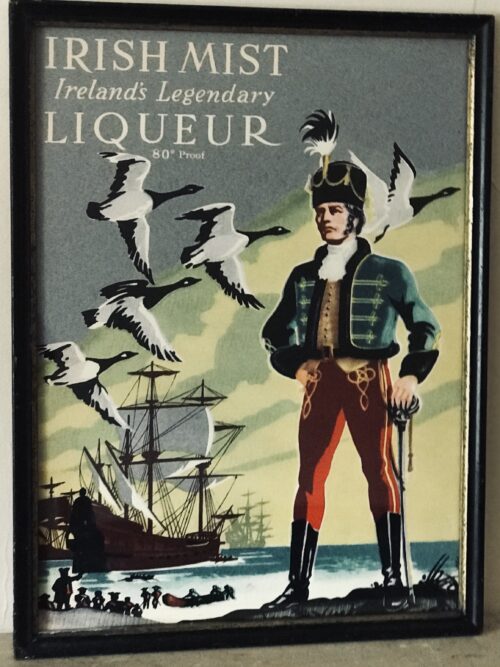

Lovely Irish Mist advertising print depicting the iconic Irish soldier exiled and serving in the Irish Regiment of the Austrian Army around the mid 1750s. Nenagh Co Tipperary 50cm x 40cm Irish Mist is a brown Whiskey Liqueur produced in Dublin, Ireland, by the Irish Mist Liqueur Company Ltd. In September 2010 it was announced that the brand was being bought by Gruppo Campari from William Grant, only a few months after Grants had bought it from the C&C Group. It is made from aged Irish whiskey, heather and clover honey, aromatic herbs, and other spirits, blended to an ancient recipe claimed to be 1,000 years old.Though it was once 80 US proof (40% alcohol per volume), Irish Mist is now 35% or 70 US proof. The bottle shape has also been changed from a “decanter” style to a more traditional whiskey bottle shape. It is currently available in more than 40 countries. Irish Mist was the first liqueur to be produced in Ireland when commercial production began in 1947 at Tullamore, County Offaly. Tullamore is the hometown of the Williams family who were the original owners of Irish Mist. The company history goes back to 1829 when the Tullamore Distillery was founded to produce Irish whiskey. In the mid-1940s Desmond E. Williams began the search for an alternative yet related product, eventually deciding to produce a liqueur based on the ancient beverage known as heather wine.In 1985 the Cantrell & Cochrane Group purchased the Irish Mist Liqueur Company from the Williams family. In the summer of 2010 Irish Mist and the entire spirit division of C&C was bought by William Grant of Scotland. In September 2010 they in turn sold Irish Mist to Gruppo Campari.Irish Mist is typically served straight up or on ice, but also goes with coffee, vodka, or cranberry juice. Per the makers, Irish Mist’s most popular recipe is Irish Mist with Cola and Lime. A Rusty Mist is an ounce of Irish Mist with an ounce of Drambuie Scotch whisky liqueur.A Black Nail is made from equal parts Irish Mist and Irish whiskey.

Lovely Irish Mist advertising print depicting the iconic Irish soldier exiled and serving in the Irish Regiment of the Austrian Army around the mid 1750s. Nenagh Co Tipperary 50cm x 40cm Irish Mist is a brown Whiskey Liqueur produced in Dublin, Ireland, by the Irish Mist Liqueur Company Ltd. In September 2010 it was announced that the brand was being bought by Gruppo Campari from William Grant, only a few months after Grants had bought it from the C&C Group. It is made from aged Irish whiskey, heather and clover honey, aromatic herbs, and other spirits, blended to an ancient recipe claimed to be 1,000 years old.Though it was once 80 US proof (40% alcohol per volume), Irish Mist is now 35% or 70 US proof. The bottle shape has also been changed from a “decanter” style to a more traditional whiskey bottle shape. It is currently available in more than 40 countries. Irish Mist was the first liqueur to be produced in Ireland when commercial production began in 1947 at Tullamore, County Offaly. Tullamore is the hometown of the Williams family who were the original owners of Irish Mist. The company history goes back to 1829 when the Tullamore Distillery was founded to produce Irish whiskey. In the mid-1940s Desmond E. Williams began the search for an alternative yet related product, eventually deciding to produce a liqueur based on the ancient beverage known as heather wine.In 1985 the Cantrell & Cochrane Group purchased the Irish Mist Liqueur Company from the Williams family. In the summer of 2010 Irish Mist and the entire spirit division of C&C was bought by William Grant of Scotland. In September 2010 they in turn sold Irish Mist to Gruppo Campari.Irish Mist is typically served straight up or on ice, but also goes with coffee, vodka, or cranberry juice. Per the makers, Irish Mist’s most popular recipe is Irish Mist with Cola and Lime. A Rusty Mist is an ounce of Irish Mist with an ounce of Drambuie Scotch whisky liqueur.A Black Nail is made from equal parts Irish Mist and Irish whiskey. -

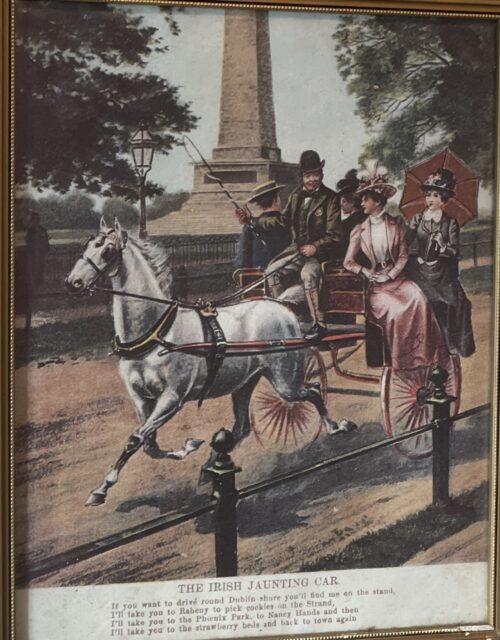

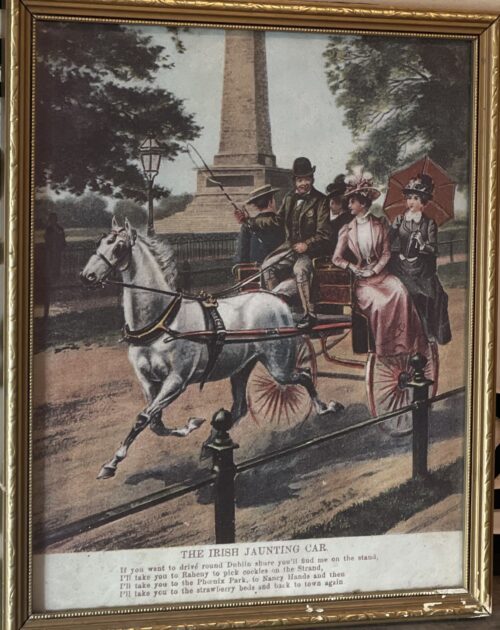

58cm x 42cm Quaint vintage poster of a jaunting car carrying a group around Phoenix Park- the giant Wellington monument can be seen in the background. The Wellington Monument or sometimes the Wellington Testimonial,is an obelisk located in the Phoenix Park, Dublin, Ireland. The testimonial is situated at the southeast end of the Park, overlooking Kilmainham and the River Liffey. The structure is 62 metres (203 ft) tall, making it the largest obelisk in Europe

58cm x 42cm Quaint vintage poster of a jaunting car carrying a group around Phoenix Park- the giant Wellington monument can be seen in the background. The Wellington Monument or sometimes the Wellington Testimonial,is an obelisk located in the Phoenix Park, Dublin, Ireland. The testimonial is situated at the southeast end of the Park, overlooking Kilmainham and the River Liffey. The structure is 62 metres (203 ft) tall, making it the largest obelisk in EuropeHistory

The Wellington Testimonial was built to commemorate the victories of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington. Wellington, the British politician and general, also known as the 'Iron Duke', was born in Ireland. Originally planned to be located in Merrion Square, it was built in the Phoenix Park after opposition from the square's residents. The obelisk was designed by the architect Sir Robert Smirke and the foundation stone was laid in 1817. In 1820, the project ran out of construction funds and the structure remained unfinished until 18 June 1861 when it was opened to the public. There were also plans for a statue of Wellington on horseback, but a shortage of funds ruled that out.Features

There are four bronze plaques cast from cannons captured at Waterloo – three of which have pictorial representations of his career while the fourth has an inscription. The plaques depict 'Civil and Religious Liberty' by John Hogan, 'Waterloo' by Thomas Farrell and the 'Indian Wars' by Joseph Robinson Kirk. The inscription reads:- Asia and Europe, saved by thee, proclaim

- Invincible in war thy deathless name,

- Now round thy brow the civic oak we twine

- That every earthly glory may be thine.

Cultural references

The monument is referenced throughout James Joyce's Finnegans Wake. The first page of the novel alludes to a giant whose head is at "Howth Castle and Environs" and whose toes are at "a knock out in the park (p. 3)"; John Bishop extends the analogy, interpreting this centrally located obelisk as the prone giant's male member. A few pages later, the monument is the site of the fictional "Willingdone Museyroom" (p. 8). -

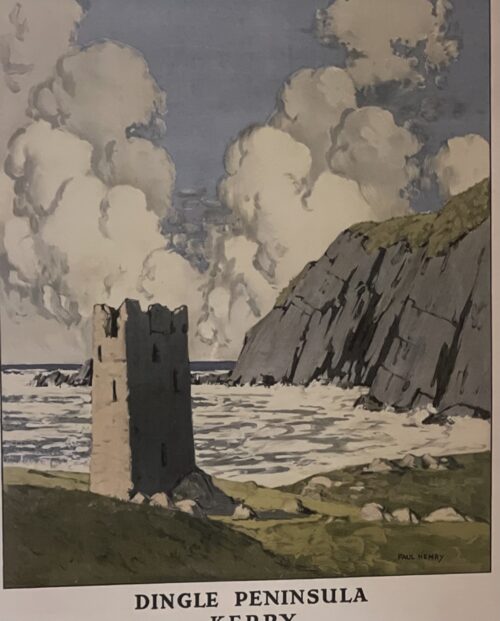

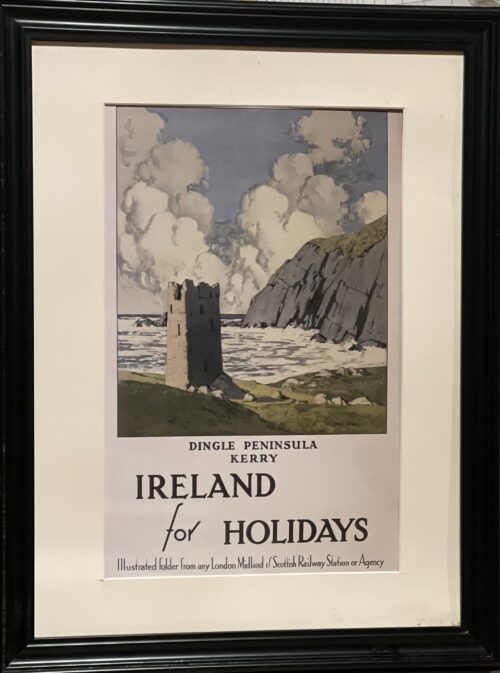

52cm x 44cm The London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) was a British railway company. It was formed on 1 January 1923 under the Railways Act of 1921,which required the grouping of over 120 separate railways into four. The companies merged into the LMS included the London and North Western Railway, Midland Railway, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (which had previously merged with the London and North Western Railway on 1 January 1922), several Scottish railway companies (including the Caledonian Railway), and numerous other, smaller ventures. Besides being the world's largest transport organisation, the company was also the largest commercial enterprise in the British Empire and the United Kingdom's second largest employer, after the Post Office. In 1938, the LMS operated 6,870 miles (11,056 km) of railway (excluding its lines in Northern Ireland), but its profitability was generally disappointing, with a rate of return of only 2.7%. Under the Transport Act 1947, along with the other members of the "Big Four" British railway companies (Great Western Railway, London and North Eastern Railway and Southern Railway), the LMS was nationalised on 1 January 1948, becoming part of the state-owned British Railways. The LMS was the largest of the Big Four railway companies serving routes in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The LMS's commercial success in the 1920s resulted in part from the contributions of English painter, Norman Wilkinson. In 1923, Wilkinson advised Superintendent of Advertising and Publicity of the LMS, T.C Jeffrey, to improve rail sales and other LMS services by incorporating fine art into the design of their advertisement posters. In this time, fine art already had a distinguished association in Europe and North America with good taste, longevity and quality.[26] Jeffrey wanted LMS’ commercial image to align with these qualities and therefore accepted Wilkinson's advice.[27] For the first series of posters, Wilkinson personally invited 16 of his fellow alumni from the Royal Academy of London to take part. In letter correspondence, Wilkinson outlined the details of the LMS proposal to the artists.The artist fee for each participant was £100. The railway poster would measure 50 X 40 inches. In this area, the artist's design would be reproduced as a photolithographic print on double royal satin paper, filling 45 X 35 inches. The mass-produced posters were pasted inside railway stations in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. LMS decided the subject advertised, but choices of style and approach were left to the artist's discretion. LMS’ open design brief resulted in a collection of posters that reflected the large capacity of destinations and experiences available with the transport organisation.For the Irish Free State, Wilkinson designed a poster in 1927 encouraging the public to avail of the LMS ferry and connecting boat trains to Ireland. For this promotion, Wilkinson's design was accompanied with four posters of Ireland by Belfast modernist painter, Paul Henry. The commercial success of Wilkinson and Jeffrey's collaboration manifested between 1924 and 1928, with public sale of 12,000 railway posters.Paul Henry's 1925 poster depicting the Gaeltacht region of Connemara in County Galway proved most commercially popular, with 1,500 sales. Paul Henry (11 April 1876 – 24 August 1958) was an Irish artist noted for depicting the West of Ireland landscape in a spare Post-Impressioniststyle. Henry was born at 61 University Road, Belfast, Ireland, the son of the Rev Robert Mitchell Henry, a Baptist minister (who later joined the Plymouth Brethren), and Kate Ann Berry. Henry began studying at Methodist College Belfast in 1882 where he first began drawing regularly. At the age of fifteen he moved to the Royal Belfast Academical Institution.He studied art at the Belfast School of Art before going to Paris in 1898 to study at the Académie Julian and at Whistler's Académie Carmen. He married the painter Grace Henry in 1903 and returned to Ireland in 1910. From then until 1919 he lived on Achill Island, where he learned to capture the peculiar interplay of light and landscape specific to the West of Ireland. In 1919 he moved to Dublin and in 1920 was one of the founders of the Society of Dublin Painters, originally a group of ten artists. Henry designed several railway posters, some of which, notably Connemara Landscape, achieved considerable sales.He separated from his wife in 1929. His second wife was the artist Mabel Young. In the 1920s and 1930s Henry was Ireland's best known artist, one who had a considerable influence on the popular image of the west of Ireland. Although he seems to have ceased experimenting with his technique after he left Achill and his range is limited, he created a large body of fine images whose familiarity is a testament to its influence. Henry's use of colour was affected by his red-green color blindness.He lost his sight during 1945 and did not regain his vision before his death. A commemorative exhibition of Henry's work was held at Trinity College, Dublin, in 1973 and the National Gallery of Ireland held a major exhibition of his work in 2004. A painting by Henry was featured on an episode of the BBC's Antiques Roadshow, broadcast on 12 November 2006. The painting was given a value of approximately £40,000–60,000 by the roadshow. However, due to the buoyancy of the Irish art market at that time, it sold for €260,000 on 5 December 2006 in James Adams' and Bonhams' joint Important Irish Art sale. He died at his home at 1 Sidmonton Square, Bray, County Wicklow, and was survived by his wife, Mabel.

52cm x 44cm The London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) was a British railway company. It was formed on 1 January 1923 under the Railways Act of 1921,which required the grouping of over 120 separate railways into four. The companies merged into the LMS included the London and North Western Railway, Midland Railway, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (which had previously merged with the London and North Western Railway on 1 January 1922), several Scottish railway companies (including the Caledonian Railway), and numerous other, smaller ventures. Besides being the world's largest transport organisation, the company was also the largest commercial enterprise in the British Empire and the United Kingdom's second largest employer, after the Post Office. In 1938, the LMS operated 6,870 miles (11,056 km) of railway (excluding its lines in Northern Ireland), but its profitability was generally disappointing, with a rate of return of only 2.7%. Under the Transport Act 1947, along with the other members of the "Big Four" British railway companies (Great Western Railway, London and North Eastern Railway and Southern Railway), the LMS was nationalised on 1 January 1948, becoming part of the state-owned British Railways. The LMS was the largest of the Big Four railway companies serving routes in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The LMS's commercial success in the 1920s resulted in part from the contributions of English painter, Norman Wilkinson. In 1923, Wilkinson advised Superintendent of Advertising and Publicity of the LMS, T.C Jeffrey, to improve rail sales and other LMS services by incorporating fine art into the design of their advertisement posters. In this time, fine art already had a distinguished association in Europe and North America with good taste, longevity and quality.[26] Jeffrey wanted LMS’ commercial image to align with these qualities and therefore accepted Wilkinson's advice.[27] For the first series of posters, Wilkinson personally invited 16 of his fellow alumni from the Royal Academy of London to take part. In letter correspondence, Wilkinson outlined the details of the LMS proposal to the artists.The artist fee for each participant was £100. The railway poster would measure 50 X 40 inches. In this area, the artist's design would be reproduced as a photolithographic print on double royal satin paper, filling 45 X 35 inches. The mass-produced posters were pasted inside railway stations in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. LMS decided the subject advertised, but choices of style and approach were left to the artist's discretion. LMS’ open design brief resulted in a collection of posters that reflected the large capacity of destinations and experiences available with the transport organisation.For the Irish Free State, Wilkinson designed a poster in 1927 encouraging the public to avail of the LMS ferry and connecting boat trains to Ireland. For this promotion, Wilkinson's design was accompanied with four posters of Ireland by Belfast modernist painter, Paul Henry. The commercial success of Wilkinson and Jeffrey's collaboration manifested between 1924 and 1928, with public sale of 12,000 railway posters.Paul Henry's 1925 poster depicting the Gaeltacht region of Connemara in County Galway proved most commercially popular, with 1,500 sales. Paul Henry (11 April 1876 – 24 August 1958) was an Irish artist noted for depicting the West of Ireland landscape in a spare Post-Impressioniststyle. Henry was born at 61 University Road, Belfast, Ireland, the son of the Rev Robert Mitchell Henry, a Baptist minister (who later joined the Plymouth Brethren), and Kate Ann Berry. Henry began studying at Methodist College Belfast in 1882 where he first began drawing regularly. At the age of fifteen he moved to the Royal Belfast Academical Institution.He studied art at the Belfast School of Art before going to Paris in 1898 to study at the Académie Julian and at Whistler's Académie Carmen. He married the painter Grace Henry in 1903 and returned to Ireland in 1910. From then until 1919 he lived on Achill Island, where he learned to capture the peculiar interplay of light and landscape specific to the West of Ireland. In 1919 he moved to Dublin and in 1920 was one of the founders of the Society of Dublin Painters, originally a group of ten artists. Henry designed several railway posters, some of which, notably Connemara Landscape, achieved considerable sales.He separated from his wife in 1929. His second wife was the artist Mabel Young. In the 1920s and 1930s Henry was Ireland's best known artist, one who had a considerable influence on the popular image of the west of Ireland. Although he seems to have ceased experimenting with his technique after he left Achill and his range is limited, he created a large body of fine images whose familiarity is a testament to its influence. Henry's use of colour was affected by his red-green color blindness.He lost his sight during 1945 and did not regain his vision before his death. A commemorative exhibition of Henry's work was held at Trinity College, Dublin, in 1973 and the National Gallery of Ireland held a major exhibition of his work in 2004. A painting by Henry was featured on an episode of the BBC's Antiques Roadshow, broadcast on 12 November 2006. The painting was given a value of approximately £40,000–60,000 by the roadshow. However, due to the buoyancy of the Irish art market at that time, it sold for €260,000 on 5 December 2006 in James Adams' and Bonhams' joint Important Irish Art sale. He died at his home at 1 Sidmonton Square, Bray, County Wicklow, and was survived by his wife, Mabel. -

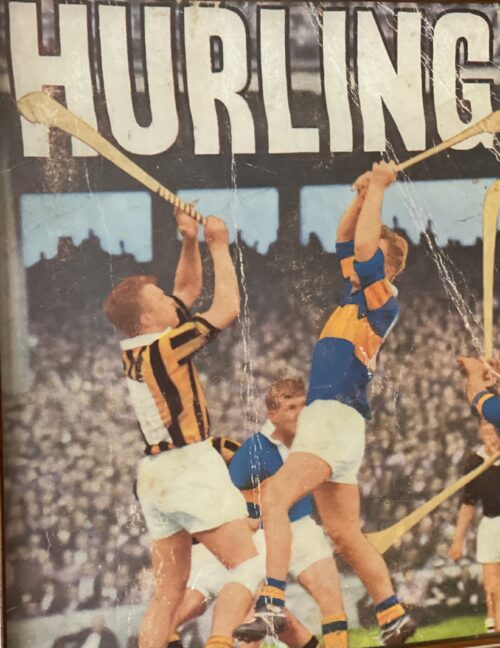

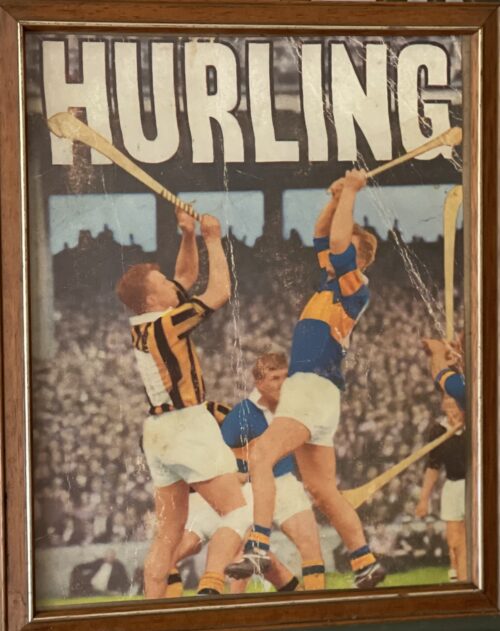

40cm x 34cm Hurling (Irish: iománaíocht, iomáint) is an outdoor team game of ancient Gaelic Irish origin, played by men. One of Ireland's native Gaelic games, it shares a number of features with Gaelic football, such as the field and goals, the number of players, and much terminology. There is a similar game for women called camogie (camógaíocht). It shares a common Gaelic root. The objective of the game is for players to use an ash wood stick called a hurley (in Irish a camán, pronounced /ˈkæmən/or /kəˈmɔːn/) to hit a small ball called a sliotar /ˈʃlɪtər/ between the opponents' goalposts either over the crossbar for one point, or under the crossbar into a net guarded by a goalkeeper for three points. The sliotar can be caught in the hand and carried for not more than four steps, struck in the air, or struck on the ground with the hurley. It can be kicked, or slapped with an open hand (the hand pass) for short-range passing. A player who wants to carry the ball for more than four steps has to bounce or balance the sliotar on the end of the stick, and the ball can only be handled twice while in the player’s possession. Provided that a player has at least one foot on the ground, a player may make a shoulder-to-shoulder charge on an opponent who is in possession of the ball or is playing the ball or when both players are moving in the direction of the ball to play it. No protective padding is worn by players. A plastic protective helmet with a faceguard is mandatory for all age groups, including senior level, as of 2010. The game has been described as "a bastion of humility", with player names absent from jerseys and a player's number decided by his position on the field. Hurling is administered by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA). It is played throughout the world, and is popular among members of the Irish diaspora in North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Argentina, and South Korea. In many parts of Ireland, however, hurling is a fixture of life.It has featured regularly in art forms such as film, music and literature. The final of the All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship was listed in second place by CNN in its "10 sporting events you have to see live", after the Olympic Games and ahead of both the FIFA World Cup and UEFA European Championship.After covering the 1959 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final between Kilkenny and Waterford for BBC Television, English commentator Kenneth Wolstenholme was moved to describe hurling as his second favourite sport in the world after his first love, football.Alex Ferguson used footage of an All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship final in an attempt to motivate his players during his time as manager of Premier League football club Manchester United; the players winced at the standard of physicality and intensity in which the hurlers were engaged. In 2007, Forbes magazine described the media attention and population multiplication of Thurles town ahead of one of the game's annual provincial hurling finals as being "the rough equivalent of 30 million Americans watching a regional lacrosse game".Financial Times columnist Simon Kuper wrote after Stephen Bennett's performance in the 2020 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final that hurling was "the best sport ever and if the Irish had colonised the world, nobody would ever have heard of football" UNESCO lists hurling as an element of Intangible cultural heritage.

40cm x 34cm Hurling (Irish: iománaíocht, iomáint) is an outdoor team game of ancient Gaelic Irish origin, played by men. One of Ireland's native Gaelic games, it shares a number of features with Gaelic football, such as the field and goals, the number of players, and much terminology. There is a similar game for women called camogie (camógaíocht). It shares a common Gaelic root. The objective of the game is for players to use an ash wood stick called a hurley (in Irish a camán, pronounced /ˈkæmən/or /kəˈmɔːn/) to hit a small ball called a sliotar /ˈʃlɪtər/ between the opponents' goalposts either over the crossbar for one point, or under the crossbar into a net guarded by a goalkeeper for three points. The sliotar can be caught in the hand and carried for not more than four steps, struck in the air, or struck on the ground with the hurley. It can be kicked, or slapped with an open hand (the hand pass) for short-range passing. A player who wants to carry the ball for more than four steps has to bounce or balance the sliotar on the end of the stick, and the ball can only be handled twice while in the player’s possession. Provided that a player has at least one foot on the ground, a player may make a shoulder-to-shoulder charge on an opponent who is in possession of the ball or is playing the ball or when both players are moving in the direction of the ball to play it. No protective padding is worn by players. A plastic protective helmet with a faceguard is mandatory for all age groups, including senior level, as of 2010. The game has been described as "a bastion of humility", with player names absent from jerseys and a player's number decided by his position on the field. Hurling is administered by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA). It is played throughout the world, and is popular among members of the Irish diaspora in North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Argentina, and South Korea. In many parts of Ireland, however, hurling is a fixture of life.It has featured regularly in art forms such as film, music and literature. The final of the All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship was listed in second place by CNN in its "10 sporting events you have to see live", after the Olympic Games and ahead of both the FIFA World Cup and UEFA European Championship.After covering the 1959 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final between Kilkenny and Waterford for BBC Television, English commentator Kenneth Wolstenholme was moved to describe hurling as his second favourite sport in the world after his first love, football.Alex Ferguson used footage of an All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship final in an attempt to motivate his players during his time as manager of Premier League football club Manchester United; the players winced at the standard of physicality and intensity in which the hurlers were engaged. In 2007, Forbes magazine described the media attention and population multiplication of Thurles town ahead of one of the game's annual provincial hurling finals as being "the rough equivalent of 30 million Americans watching a regional lacrosse game".Financial Times columnist Simon Kuper wrote after Stephen Bennett's performance in the 2020 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final that hurling was "the best sport ever and if the Irish had colonised the world, nobody would ever have heard of football" UNESCO lists hurling as an element of Intangible cultural heritage. -

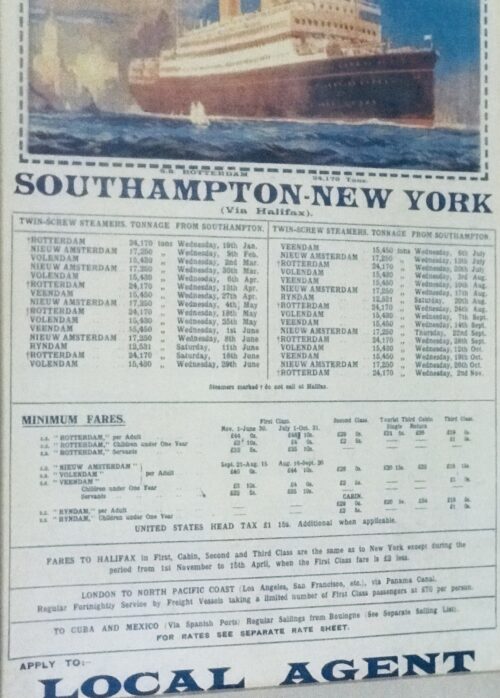

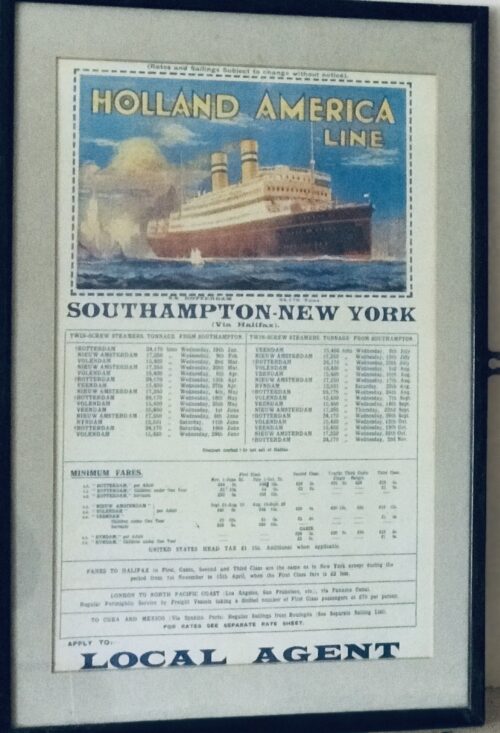

50cm x 35cm Birr Co Offaly "The Holland-America Line, a steamship company with passenger and freight steamers plying between Rotterdam and New York, is the only steamship line carrying emigrants from the Netherlands to the United States of America. Emigrants from the interior of the continent of Europe, who purchase their steamship tickets from the branch offices of the Holland-America Line in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy, arrive in Rotterdam on international trains, in which several cars have been set apart for their accommodation, from five to six days before the departure of the steamer on which they expect to sail; while emigrants from parts not far distant from this city, like southern Germany and the interior of the Netherlands, arrive at Rotterdam by train and river boat until the day previous to the departure of the steamer. All emigrants for the Holland-America Line are met at the railway station and boat landing at Rotterdam by runners of the line, who conduct them, immediately upon arrival, per steam tug to the NASM Hotel, the emigrant hotel owned and controlled by the Holland-America Line and situated opposite to the line's wharf. Here the emigrants remain until the departure of the steamer on which they are to sail or, in case they should be found undesirable immigrants by one of the medical inspectors, by the steamship company, or by the consul-general or vice-consul-general, until the time that they are returned again to the countries whence they came. The NASM Hotel was designed and built exclusively for the accommodation of the immigrants traveling per Holland-America Line. In the construction, besides the comfort of the emigrants, the sanitary requirements for a building of its kind have been given due consideration. The dining rooms and coffee or conversation rooms are, though necessarily somewhat sober in appearance in order to insure cleanliness, bright, spacious, and pleasant. The dormitories are spacious, clean, and airy. Sleeping apartments, open on top, each containing from four to six iron berths, similar to those used in the steerage of the company's twin-screw steamers, have been partitioned off along the walls. This gives the immigrants the desired privacy, besides the advantage of being together with the members of their family in one apartment. Between the partitions a wide space is left in the center of the dormitories for chairs, tables, etc., while windows and ventilators provide light and air on every side. There are separate dormitories for families, for men, and for women. Spacious wash and bath rooms, with modern appointments, are located on the vestibules conveniently close to each dormitory. The hotel has been constructed in such a manner that, should the need at any time arise, it would be possible to quarantine 800 passengers within its walls as effectually as though they were on shipboard. This possibility of isolation before sailing is a great sanitary advantage. With reference to this hotel, Consul Listoe wrote in his dispatch to the Department of State, under date of April 6, 1900: The company's claim that it is furnishing good lodging and board for emigrants at a low figure and at the same time protecting them against low, boardinghouse runners and sharpers, who would fleece them, is correct, and the Holland America Line is entitled to a great deal of credit for the humane manner in which it treats and cares for its emigrants. What is of more importance, though, from a United States point of view, is the facilities furnished the examining physician at the NASM Hotel for inspecting the emigrants as well as the arrangements for cleaning, bathing, and disinfecting the latter, and taking other sanitary measures in connection with those prospective citizens of the United States. At the hotel the emigrants are, at the instance of the Holland America Line, daily subjected to a medical inspection by a Dutch physician in the employ of the line. One day before sailing the emigrants are inspected at the hotel by a prominent Rotterdam oculist, engaged by the steamship company for its own protection,' to prevent emigrants suffering from infectious eye diseases sailing on its steamers. As the medical inspections referred to are not those prescribed by the United States Quarantine Regulations, they are not witnessed by a consular officer. The work of consular inspection is carried on as follows: The day previous to the departure of a passenger steamer, the baggage of all steerage passengers is inspected by the consul-general or his deputy. Among this baggage large quantities of mildewed and otherwise spoiled eatables are found. These are taken out, this having been the practice of the Marine-Hospital surgeon formerly detailed at Rotterdam. All feather pillows and beds are taken from the baggage and undergo a steam disinfection of 1000 Cel. As many as 60 beds can be disinfected at the same time by the Holland-America Line's disinfection plants, and each disinfection will require about one and one-half hours, viz, half an hour for getting up the required steam heat, half an hour for the disinfection, and half an hour for drying purposes. When there are 200 beds or more to be disinfected, which is frequently the case, supervision of the disinfection will keep a consular officer engaged for several hours. The inspection of the baggage takes from two to four hours, according to the number of packages to be inspected. The last medical and general inspection of the emigrants at which the consul-general or vice-consul-general is present is the inspection prescribed by the Quarantine Regulations, page I5, paragraph 5. It takes place in the hotel of the Holland-American Line or in the line's covered warehouse and· begins from three to six hours before the departure of the steamer. The emigrants pass in single file before the ship's surgeon, an American physician, who inspects them in the presence of the consular officer, who, for his part, looks over their inspection cards, prescribed by the Quarantine Regulations, page 19, paragraph 40, and stamps the same with a consular rubber seal, for all emigrants approved of. There are also present an officer of the State commission controlling the transit of emigrants through the Netherlands, who tallies their numbers, and a Rotterdam police officer, who watches for fugitives from justice among them reported to the Netherlands police authorities. Immediately after the inspection, the emigrants in possession of inspection cards bearing the consular stamp board the steamer and enter the steerage, which has previously been inspected by the consul. A few minutes before departure, after looking over the freight manifests of the vessel to see if all the requirements of the Quarantine Regulations and of the regulations of the Department of Agriculture have been complied with reference to disinfection certificates and certificates of healthy origin, the bill of health is issued. The emigrants are vaccinated by the ship's surgeon as soon as practicable after the departure of the vessel. Of late years no emigrants from infected districts have passed through Rotterdam on their way to the United States. Should such occur at any time, then they can be effectually quarantined in the hotel of the Holland-America Line for the periods prescribed by the Quarantine Regulations. AIRE H. VOORWINDEN, Vice and Deputy Consul- Gtneral. In a letter by Mr. Voorwinden to Mr. Peirce. CONSULATE-GENERAL, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Rotterdam, Netherlands, September 23 1903.

50cm x 35cm Birr Co Offaly "The Holland-America Line, a steamship company with passenger and freight steamers plying between Rotterdam and New York, is the only steamship line carrying emigrants from the Netherlands to the United States of America. Emigrants from the interior of the continent of Europe, who purchase their steamship tickets from the branch offices of the Holland-America Line in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy, arrive in Rotterdam on international trains, in which several cars have been set apart for their accommodation, from five to six days before the departure of the steamer on which they expect to sail; while emigrants from parts not far distant from this city, like southern Germany and the interior of the Netherlands, arrive at Rotterdam by train and river boat until the day previous to the departure of the steamer. All emigrants for the Holland-America Line are met at the railway station and boat landing at Rotterdam by runners of the line, who conduct them, immediately upon arrival, per steam tug to the NASM Hotel, the emigrant hotel owned and controlled by the Holland-America Line and situated opposite to the line's wharf. Here the emigrants remain until the departure of the steamer on which they are to sail or, in case they should be found undesirable immigrants by one of the medical inspectors, by the steamship company, or by the consul-general or vice-consul-general, until the time that they are returned again to the countries whence they came. The NASM Hotel was designed and built exclusively for the accommodation of the immigrants traveling per Holland-America Line. In the construction, besides the comfort of the emigrants, the sanitary requirements for a building of its kind have been given due consideration. The dining rooms and coffee or conversation rooms are, though necessarily somewhat sober in appearance in order to insure cleanliness, bright, spacious, and pleasant. The dormitories are spacious, clean, and airy. Sleeping apartments, open on top, each containing from four to six iron berths, similar to those used in the steerage of the company's twin-screw steamers, have been partitioned off along the walls. This gives the immigrants the desired privacy, besides the advantage of being together with the members of their family in one apartment. Between the partitions a wide space is left in the center of the dormitories for chairs, tables, etc., while windows and ventilators provide light and air on every side. There are separate dormitories for families, for men, and for women. Spacious wash and bath rooms, with modern appointments, are located on the vestibules conveniently close to each dormitory. The hotel has been constructed in such a manner that, should the need at any time arise, it would be possible to quarantine 800 passengers within its walls as effectually as though they were on shipboard. This possibility of isolation before sailing is a great sanitary advantage. With reference to this hotel, Consul Listoe wrote in his dispatch to the Department of State, under date of April 6, 1900: The company's claim that it is furnishing good lodging and board for emigrants at a low figure and at the same time protecting them against low, boardinghouse runners and sharpers, who would fleece them, is correct, and the Holland America Line is entitled to a great deal of credit for the humane manner in which it treats and cares for its emigrants. What is of more importance, though, from a United States point of view, is the facilities furnished the examining physician at the NASM Hotel for inspecting the emigrants as well as the arrangements for cleaning, bathing, and disinfecting the latter, and taking other sanitary measures in connection with those prospective citizens of the United States. At the hotel the emigrants are, at the instance of the Holland America Line, daily subjected to a medical inspection by a Dutch physician in the employ of the line. One day before sailing the emigrants are inspected at the hotel by a prominent Rotterdam oculist, engaged by the steamship company for its own protection,' to prevent emigrants suffering from infectious eye diseases sailing on its steamers. As the medical inspections referred to are not those prescribed by the United States Quarantine Regulations, they are not witnessed by a consular officer. The work of consular inspection is carried on as follows: The day previous to the departure of a passenger steamer, the baggage of all steerage passengers is inspected by the consul-general or his deputy. Among this baggage large quantities of mildewed and otherwise spoiled eatables are found. These are taken out, this having been the practice of the Marine-Hospital surgeon formerly detailed at Rotterdam. All feather pillows and beds are taken from the baggage and undergo a steam disinfection of 1000 Cel. As many as 60 beds can be disinfected at the same time by the Holland-America Line's disinfection plants, and each disinfection will require about one and one-half hours, viz, half an hour for getting up the required steam heat, half an hour for the disinfection, and half an hour for drying purposes. When there are 200 beds or more to be disinfected, which is frequently the case, supervision of the disinfection will keep a consular officer engaged for several hours. The inspection of the baggage takes from two to four hours, according to the number of packages to be inspected. The last medical and general inspection of the emigrants at which the consul-general or vice-consul-general is present is the inspection prescribed by the Quarantine Regulations, page I5, paragraph 5. It takes place in the hotel of the Holland-American Line or in the line's covered warehouse and· begins from three to six hours before the departure of the steamer. The emigrants pass in single file before the ship's surgeon, an American physician, who inspects them in the presence of the consular officer, who, for his part, looks over their inspection cards, prescribed by the Quarantine Regulations, page 19, paragraph 40, and stamps the same with a consular rubber seal, for all emigrants approved of. There are also present an officer of the State commission controlling the transit of emigrants through the Netherlands, who tallies their numbers, and a Rotterdam police officer, who watches for fugitives from justice among them reported to the Netherlands police authorities. Immediately after the inspection, the emigrants in possession of inspection cards bearing the consular stamp board the steamer and enter the steerage, which has previously been inspected by the consul. A few minutes before departure, after looking over the freight manifests of the vessel to see if all the requirements of the Quarantine Regulations and of the regulations of the Department of Agriculture have been complied with reference to disinfection certificates and certificates of healthy origin, the bill of health is issued. The emigrants are vaccinated by the ship's surgeon as soon as practicable after the departure of the vessel. Of late years no emigrants from infected districts have passed through Rotterdam on their way to the United States. Should such occur at any time, then they can be effectually quarantined in the hotel of the Holland-America Line for the periods prescribed by the Quarantine Regulations. AIRE H. VOORWINDEN, Vice and Deputy Consul- Gtneral. In a letter by Mr. Voorwinden to Mr. Peirce. CONSULATE-GENERAL, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Rotterdam, Netherlands, September 23 1903. -

Hobnailed boots were made by Irish craftsmen – bootmakers called ‘Greasai Bróg’ in Irish. These boots were made to order and would last a lifetime. The very thick soles are almost completely covered with hobnails and the stout heels are protected by an almost horseshoe-shaped iron tip. You can be guaranteed that if these boots could talk they could tell some stories ! A wonderful item for any historical display . They are an approximate size 9 1/2. Letterfrack Co Galway

Hobnailed boots were made by Irish craftsmen – bootmakers called ‘Greasai Bróg’ in Irish. These boots were made to order and would last a lifetime. The very thick soles are almost completely covered with hobnails and the stout heels are protected by an almost horseshoe-shaped iron tip. You can be guaranteed that if these boots could talk they could tell some stories ! A wonderful item for any historical display . They are an approximate size 9 1/2. Letterfrack Co Galway -

Hobnailed boots were made by Irish craftsmen – bootmakers called ‘Greasai Bróg’ in Irish. These boots were made to order and would last a lifetime. The very thick soles are almost completely covered with hobnails and the stout heels are protected by an almost horseshoe-shaped iron tip. You can be guaranteed that if these boots could talk they could tell some stories ! A wonderful item for any historical display . They are an approximate size 9. Clifden Co Galway

Hobnailed boots were made by Irish craftsmen – bootmakers called ‘Greasai Bróg’ in Irish. These boots were made to order and would last a lifetime. The very thick soles are almost completely covered with hobnails and the stout heels are protected by an almost horseshoe-shaped iron tip. You can be guaranteed that if these boots could talk they could tell some stories ! A wonderful item for any historical display . They are an approximate size 9. Clifden Co Galway -