-

Pre game team photo of the 1981 All Ireland Hurling Champions-Offaly 48cm x 59cm Birr Co Offaly 1981 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final was the 94th All-Ireland Final and the culmination of the 1981 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship, an inter-county hurling tournament for the top teams in Ireland. The match was held at Croke Park, Dublin, on 6 September 1981, between Galway and Offaly. The reigning champions lost to their Leinster opponents, who won their first ever senior hurling title, on a score line of 2-12 to 0-15. Johnny Flaherty scored a handpassed goal in this game; this was before the handpassed goal was ruled out of the game as hurling's technical standards improved.

Pre game team photo of the 1981 All Ireland Hurling Champions-Offaly 48cm x 59cm Birr Co Offaly 1981 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final was the 94th All-Ireland Final and the culmination of the 1981 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship, an inter-county hurling tournament for the top teams in Ireland. The match was held at Croke Park, Dublin, on 6 September 1981, between Galway and Offaly. The reigning champions lost to their Leinster opponents, who won their first ever senior hurling title, on a score line of 2-12 to 0-15. Johnny Flaherty scored a handpassed goal in this game; this was before the handpassed goal was ruled out of the game as hurling's technical standards improved. -

48cm x 59cm Pre Match Team photo of the 1972 All Ireland hurling champions -Kilkenny

48cm x 59cm Pre Match Team photo of the 1972 All Ireland hurling champions -KilkennyClassic All-Ireland SHC finals - 1972: Kilkenny 3-24 Cork 5-11

BRIAN CODY will have fond memories of All-Ireland hurling final day in 1972.

Brian Cody captained his county’s minor side to victory over Cork and later that afternoon those counties produced a classic encounter which ended in a spectacular victory for a Kilkenny team captained by goalkeeper Noel Skehan. Cork were firm favourites after hammering Clare in the Munster final (6-18 to 2-8), while Kilkenny had been taken to a replay by Wexford in the Leinster decider. The game was a thrilling contest. Cork dominated the early exchanges and went eight points clear after a long-range score from wing-back Con Roche in the 17th minute of the second half. Remarkably the Rebels didn’t score again. Kilkenny took control with Pat Henderson a key figure at centre-back and Eddie Keher cutting loose up front. They were level after Frank Cummins goal and went onto win by eight points. Scorers for Kilkenny: E Keher (2-9, 1-7 frees); L O’Brien (0-5, three frees); P Delaney (0-3); F Cummins (1-0); K Purcell (0-2); M Crotty (0-2); P Henderson (0-1, free); M Murphy (0-1); J Kinsella (0-1). Scorers for Cork: R Cummins (2-3); M Malone (2-1); C McCarthy (0-4, three frees); S O’Leary (1-1); C Roche (0-2, one free). KILKENNY: N Skehan (c); F Larkin, P Dillon, J Treacy; P Lawlor, P Henderson, E Morrissey; F Cummins, L O’Brien; M Crotty, P Delaney, J Kinsella; E Byrne, K Purcell, E Keher.Subs: M Murphy for Byrne (ht); M Coogan for Larkin (injured, 49); P Moran for Kinsella (75).CORK: P Barry; A Maher, P McDonnell, B Murphy; F Norberg (c), S Looney, C Roche; D Coughlan, J McCarthy; G McCarthy, M Malone, P Hegarty; C McCarthy, R Cummins, S O’Leary Subs: T O’Brien for Norberg (36); D Collins for Hegarty (68); J Rothwell for G McCarthy (76). Referee: Mick Spain (Offaly). -

48cm x 59cm. Borrisokane Co Tipperary

48cm x 59cm. Borrisokane Co TipperaryTom Moloughney: 'It was a great aul' Tipperary team, we should have won five-in-a-row'

Tom Moloughney, Jimmy Doyle, and Kieran Carey relax in the dressing room after Tipperary’s victory over Dublin in the 1961 All-Ireland final, a success that was to be repeated the following year. Picture from ‘The GAA — A People’s History’What followed was a game for the ages. If not quite in quality then in thrills and spills. Wexford recovered, found themselves just a goal adrift at half-time and then took a two-point lead with 13 minutes to go before the fury of their chase emptied the tanks. A Tipp side that had lost Jimmy Doyle to a broken shoulder midway through the half took full advantage. There are no clips of the game in the usual corners of the internet today but newspaper coverage captures the world in which all this unfolded. The biggest international story of the week was the escalating tension between the US and Cuba after an incident between the respective navies while an Ireland piloted by Sean Lemass was slowly emerging from its insular existence. Telifis Eireann only began its broadcasting for the day minutes before throw-in and the schedule wrapped up long before midnight. Among the other offerings on the box that weekend were 'Kit Carson', 'The Flintstones' and a TV western series called 'The Restless Gun'. The US, after centuries of taking our people, was now beginning to give back in all sorts of ways.

Tom Moloughney, Jimmy Doyle, and Kieran Carey relax in the dressing room after Tipperary’s victory over Dublin in the 1961 All-Ireland final, a success that was to be repeated the following year. Picture from ‘The GAA — A People’s History’What followed was a game for the ages. If not quite in quality then in thrills and spills. Wexford recovered, found themselves just a goal adrift at half-time and then took a two-point lead with 13 minutes to go before the fury of their chase emptied the tanks. A Tipp side that had lost Jimmy Doyle to a broken shoulder midway through the half took full advantage. There are no clips of the game in the usual corners of the internet today but newspaper coverage captures the world in which all this unfolded. The biggest international story of the week was the escalating tension between the US and Cuba after an incident between the respective navies while an Ireland piloted by Sean Lemass was slowly emerging from its insular existence. Telifis Eireann only began its broadcasting for the day minutes before throw-in and the schedule wrapped up long before midnight. Among the other offerings on the box that weekend were 'Kit Carson', 'The Flintstones' and a TV western series called 'The Restless Gun'. The US, after centuries of taking our people, was now beginning to give back in all sorts of ways.

The 1962 All-Ireland hurling final wasn't the first time that the nation had been treated to live coverage of a game from Croke Park. That honour had been claimed by the Railway Cup hurling and football finals six months before when Clonmel's Mick Kennedy, playing for Leinster, had the honour of claiming the first ever score shown on live television. Dublin's Des Foley made his own entry into the annals by winning medals in both codes. Tipperary had seven players on the Munster hurling selection that particular St Patrick's Day. All of them would play again 24 hours later when the county side faced a Rest of Ireland selection in an exhibition in Thurles. Others to double up that same weekend were Christy Ring and Lar Foley. This was an era blessed with players whose talents would transcend time but Moloughney has no doubt that Jimmy Doyle's was the star that shone brightest. And still does.Roughly 500 people had arrived at Shannon Airport from the States and Canada on the morning of the match. A Swissair jet carrying 67 members of Toronto GAA Club was another visitor to Irish shores and these international waves were replicated on the ground. CIE laid on 25 special trains and road works on O'Connell Street made traffic jams inevitable.

“He was the best of the lot,” he declared without any hesitation. “You would go up to see Jimmy Doyle training. They used to get big crowds to watch training in Thurles at the time and I'd say they were all there for Jimmy. The things he could do! He wasn't fast but he had great anticipation. He had a brilliant hurling brain.” Moloughney's own days with Tipp lasted no more than four years, although his stint with Kilruane would stretch through to the early '70s. He regrets the brevity of his inter-county career now, and thinks maybe he could have trained as hard as the Donie Nealons or the John Doyles through winter, but there was farming to be done at the time and life goes on. Tipp kept rolling and, for the most part, they kept winning too. All-Ireland champions in 1961, their win a year later brought them level on the roll of honour with Cork on 19 and, after losing a Munster final to Waterford in 1963, they would add another pair back-to-back thanks to many of the men with whom Moloughney had soldiered. “It was a great aul Tipperary team,” he said. “We should have won five-in-a-row.” -

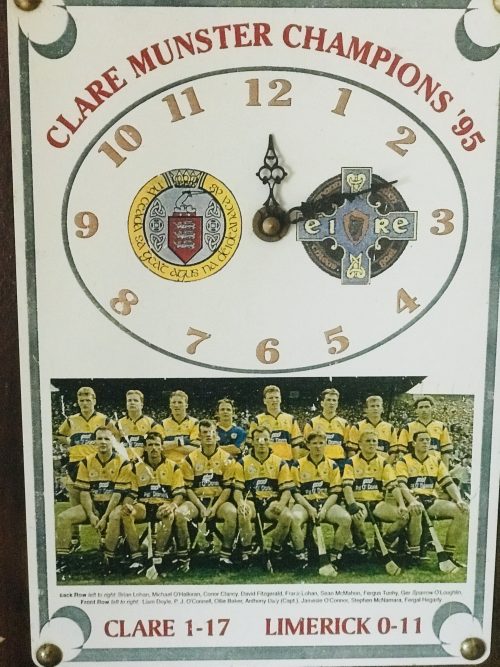

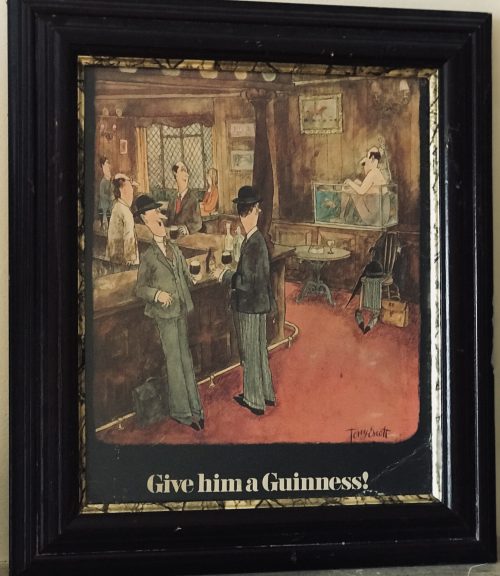

Origins : Scarriff Co Clare Dimensions: 32cm x 20cmViewed from a distance of two decades, maybe the most remarkable thing about the hurling summer of 1995 is just how unpromising it was roundly agreed to be at the get-go. The previous year had been airily dismissed as something of a freak – never more freakish than in that harum-scarum end to the All-Ireland final when Offaly overturned Limerick with a quickfire 2-5 in the closing minutes.Put to the pin of their collars, most judges shrugged and presumed the Liam MacCarthy would find his way back around to the blue-bloods in the end – probably to Kilkenny who had just beaten Clare in the National League final, maybe to Tipperary if they got their act together. If there was going to be a yarn, Limerick might provide it. But nobody had an inkling of what was around the corner. Or if they did, they weren’t shouting about it. Nobody was shouting about very much of anything. Hurling was what it was – guarded like the family jewels in certain parts of the land, barely amounting to a rumour in others. Tipp, Kilkenny and Cork had split five of the previous six All-Irelands between them and in a given year, you could just about half-rely on Offaly or Galway to keep them honest. For everyone else, the door looked shut. For all the sweet words and paeans that followed the game around, the championship was reduced each year to four or five games. This was pre-qualifiers, pre-back door of any kind. Galway walked into the All-Ireland semi-final each year and Antrim did the same before providing whoever they met with more or less a bye into the final. The Munster championship had its adherents but they weren’t all just as committed as they let on – when Clare met Cork in Thurles in June 1995, they did so in front of just 14,101 paying guests. The game needed shaking up. If not everyone admitted as much at the time, it didn’t escape the notice of the association’s then general director Liam Mulvihill. In his report to Congress earlier that year, he had scratched an itch that had been bugging him for most of the previous 12 months. The 1994 football championship had been the first to benefit from bringing on a title sponsor in Bank of Ireland and though an equivalent offer had been on the table for the hurling championship, Central Council pushed the plate away. Though the name of the potential sponsor wasn’t explicitly made public, everyone knew it was Guinness. More to the point, everyone knew why Central Council wouldn’t bite. As Mulvihill himself noted in his report to Congress, the offer was declined on the basis that “Central Council did not want an alcoholic drinks company associated with a major GAA competition”. As it turned out, Central Council had been deadlocked on the issue and it was the casting vote of then president Peter Quinn that put the kibosh on a deal with Guinness. Mulvihill’s disappointment was far from hidden, since he saw the wider damage caused by turning up the GAA nose at Guinness’s advances. “The unfortunate aspect of the situation,” he wrote, “is that hurling needs support on the promotion of the game much more than football.” Though it took the point of a bayonet to make them go for it, the GAA submitted in the end and on the day after the league final, a three-year partnership with Guinness was announced. The deal would be worth £1 million a year, with half going to the sport and half going to the competition in the shape of marketing. That last bit was key. Guinness came up with a marketing campaign that fairly scorched across the general consciousness. Billboards screeched out slogans that feel almost corny at this remove but made a huge impact at the same time . This man can level whole counties in one second flat. This man can reach speeds of 100mph. This man can break hearts at 70 yards Of course, all the marketing in the world can only do so much. Without a story to go alongside, the Guinness campaign might be forgotten now – or worse, remembered as an overblown blast of hot air dreamed up in some modish ad agency above in Dublin. Instead, Clare came along and changed everything. In the spring of 1995, Clare were very easy to stereotype. These were the days when the league wrapped around Christmas and in the muck and the cold and the drudgery, Clare had a fierceness to them that took advantage of any opposition that fancied a handy afternoon with the summer well off in the distance. A pain in the neck if you met them on a going day in the league but not to be relied upon on the biggest days. They had a recent, ill-starred record in Munster finals to bear that out. Heavy beatings from Tipp and Limerick in 1993 and ’94 were bad enough on their own; piled on decades of hurt going all the way back to their last title in 1932, they were toxic. On the day before the league final, new manager Ger Loughnane outlined what the coming summer would mean to them. “I’d swap everything for a Munster title. The whole lot. My whole hurling life. These fellas today, they have the chance. They can get out there and realise that this is what it is all about, that this is what you play hurling for. They can build on that and win their Munster title. That means so much to us all. They won’t have to look back and regret.” When Clare promptly lost 2-12 to 0-9 to Kilkenny in that league final, you didn’t have many takers for Loughnane’s assertion that this could be the group to turn everything around. Loughnane had been involved in 12 Munster finals as a player and selector at various levels down the years and he’d lost them all. Big talk was fine and dandy but what was there to believe in? Come the Munster championship, Clare were quietly but firmly dismissed by all and sundry. Cashman’s bookies in Cork priced their championship opener thus: Cork 2/5, Clare 9/4. A bar in Ennis had sent the Clare squad a cheque for £250 so they could have a pre-championship drink together. Anthony Daly took it instead and slapped it down on Clare to win the Munster championship at odds of 7/1. Anyone with half an interest in the game knows the rest. Or at least knows bits and pieces of it. That summer was a blazing one, the hottest for decades, and in the mind’s eye Clare’s summer is a jigsaw of sun-scorched fables and legends. Seanie McMahon and his broken collarbone, playing out the last 15 minutes against Cork at corner-forward. Ollie Baker’s bundled goal to win that game in injury-time. Limerick swept aside in the second half of the Munster final. Bonfires across the county on the Monday night. Galway put to the sword in the All-Ireland semi-final. Offaly just squeezed out in the final. Eamonn Taaffe’s goal, whipped to the net with his only touch of the sliotar all summer. Daly’s 65, Johnny Pilkington’s reply just flicking the post and missing. A first Clare All-Ireland senior title since 1914. It was all just so unlikely. After the Cork game, the cars heading home for Clare were stuck in traffic. A group of Cork teenagers stood at the side of the road as they passed, chanting Tipp, Tipp, Tipp – presuming Clare would meet and be beaten by them next day out. The notion that this was the beginning of a golden era, or that these Claremen were about to popularise the sport as never before, would still have felt ludicrous And yet here they were, All-Ireland champions in a year when hurling caught the wider imagination in a way it rarely had up to that point. The Guinness campaign had made its mark and allied to Clare’s rise, the sport was grabbing people again. Not before time. “The game had gone stale,” wrote Jimmy Barry-Murphy in The Irish Times in the run-up to the final. “This All-Ireland was one that game needed very badly. Interest was waning and this was reflected in the attendances at finals. “There was no comparison to football where the arrival of the Ulster counties as major powers generated enormous interest and a new awareness of the game. Clare have had many setbacks but they have kept battling and are now being rewarded. They have done hurling a great service.” The depth and breadth of that service became more and more apparent as the decade wore on. Attendances at the hurling championship matches ballooned. From an aggregate total of 289,281 in 1994, they rose to 543,335 in 1999. There were plenty of factors, of course – more counties with more hope, more matches with the introduction of the back-door, a growing economy, those Guinness ads. But it was Clare’s summer of 1995 that sparked it all. They weren’t a pebble in a pond that caused a few ripples. They were a boulder that landed from the clear blue sky and left a crater on the landscape. Everything changed after ’95. Not forever, just for a while. But for long enough for the game to stretch itself and grab hold of imaginations outside the usual places of worship. On the Monday night they brought Liam MacCarthy home, one of the towns that got a good rattle was Newmarket-On-Fergus. In the bedlam, the home club put up a stage and stuck any living Newmarket man who ever put on a Clare jersey up there as the backdrop while Daly and Loughnane grabbed the mic out front. One unusual face cloistered at the back of the stage was then Wexford manager Liam Griffin. Of the multitude of stories excavated by Denis Walsh for his towering book Hurling: The Revolution Years, maybe that night in Newmarket captured the giddiness of the time the best. Griffin’s father was from Clare and he’d lived there for a time in his early 20s, long enough to play club hurling and get called up to the Clare under-21s. Thus were his bona fides established for an appearance – however reluctant – up on-stage. Griffin had been in charge of Wexford for a year at that point and their summer had ended with a limp exit against Offaly away back in June. By the skin of his teeth, Griffin had survived an attempted county board putsch in the meantime and was almost certainly the only man alive who thought that the riches showering down upon Clare heads could be Wexford’s 12 months later. “Clare came and I thought, ‘This is fantastic,’” Griffin told Walsh. “I thought, ‘Jesus, the team I have are as good as these,’ and I went through them man for man. There’s no way we’re not as good as these guys. Then Clare won the All-Ireland and I went straight to Clare the following morning because I wanted to see the homecoming and now I understand why. I wanted to drive it into my own psyche.” As the speeches finished and the stage began to clear, Loughnane turned and caught Griffin’s eye. “It could be you next year,” he said. Whether he meant it or not, Griffin’s mind was made up already. He drove home convinced that Wexford could reach out and grab some of that for themselves. The next day he rang around and organised training, 51-and-a-half weeks shy of the 1996 All-Ireland final. In a world of endless trees and branches and roots, it’s obviously simplistic to say that Clare’s All-Ireland begat Wexford’s which begat all the rest of it. But what is inarguable is this – in that sun-drenched summer of 1995, everything felt possible.he 1995 Munster Senior Hurling Championship Final was a hurling match played on 9 July 1995 at Semple Stadium, Thurles, County Tipperary. It was contested by Clare and Limerick. Clare claimed their first Munster Championship since 1932 and fourth ever after beating Limerick on a scoreline of 1-17 to 0-11. Clare were leading the game by 1-5 to 0-7 at half time. With the scores at 0-5 to 0-3 in Clare's favour in the first half, Davy Fitzgerald scored from a penalty five minutes before the break, crashing the ball high into the net at the town end before sprinting back to his goal-line. In 2005 this penalty goal came fifth in the Top 20 GAA Moments poll by the Irish public. Clare were captained by Anthony Daly and managed by Ger Loughnane in his first year. Clare had defeated Cork in the semi-final by 2-13 to 3-09 to reach the final, while Limerick had defeated Tipperary by 0-16 to 0-15 in their semi-final. The match was screened live by RTÉ as part of The Sunday Game programme with commentary by Ger Canning and analysis by Éamonn Cregan.July 9 Final

Origins : Scarriff Co Clare Dimensions: 32cm x 20cmViewed from a distance of two decades, maybe the most remarkable thing about the hurling summer of 1995 is just how unpromising it was roundly agreed to be at the get-go. The previous year had been airily dismissed as something of a freak – never more freakish than in that harum-scarum end to the All-Ireland final when Offaly overturned Limerick with a quickfire 2-5 in the closing minutes.Put to the pin of their collars, most judges shrugged and presumed the Liam MacCarthy would find his way back around to the blue-bloods in the end – probably to Kilkenny who had just beaten Clare in the National League final, maybe to Tipperary if they got their act together. If there was going to be a yarn, Limerick might provide it. But nobody had an inkling of what was around the corner. Or if they did, they weren’t shouting about it. Nobody was shouting about very much of anything. Hurling was what it was – guarded like the family jewels in certain parts of the land, barely amounting to a rumour in others. Tipp, Kilkenny and Cork had split five of the previous six All-Irelands between them and in a given year, you could just about half-rely on Offaly or Galway to keep them honest. For everyone else, the door looked shut. For all the sweet words and paeans that followed the game around, the championship was reduced each year to four or five games. This was pre-qualifiers, pre-back door of any kind. Galway walked into the All-Ireland semi-final each year and Antrim did the same before providing whoever they met with more or less a bye into the final. The Munster championship had its adherents but they weren’t all just as committed as they let on – when Clare met Cork in Thurles in June 1995, they did so in front of just 14,101 paying guests. The game needed shaking up. If not everyone admitted as much at the time, it didn’t escape the notice of the association’s then general director Liam Mulvihill. In his report to Congress earlier that year, he had scratched an itch that had been bugging him for most of the previous 12 months. The 1994 football championship had been the first to benefit from bringing on a title sponsor in Bank of Ireland and though an equivalent offer had been on the table for the hurling championship, Central Council pushed the plate away. Though the name of the potential sponsor wasn’t explicitly made public, everyone knew it was Guinness. More to the point, everyone knew why Central Council wouldn’t bite. As Mulvihill himself noted in his report to Congress, the offer was declined on the basis that “Central Council did not want an alcoholic drinks company associated with a major GAA competition”. As it turned out, Central Council had been deadlocked on the issue and it was the casting vote of then president Peter Quinn that put the kibosh on a deal with Guinness. Mulvihill’s disappointment was far from hidden, since he saw the wider damage caused by turning up the GAA nose at Guinness’s advances. “The unfortunate aspect of the situation,” he wrote, “is that hurling needs support on the promotion of the game much more than football.” Though it took the point of a bayonet to make them go for it, the GAA submitted in the end and on the day after the league final, a three-year partnership with Guinness was announced. The deal would be worth £1 million a year, with half going to the sport and half going to the competition in the shape of marketing. That last bit was key. Guinness came up with a marketing campaign that fairly scorched across the general consciousness. Billboards screeched out slogans that feel almost corny at this remove but made a huge impact at the same time . This man can level whole counties in one second flat. This man can reach speeds of 100mph. This man can break hearts at 70 yards Of course, all the marketing in the world can only do so much. Without a story to go alongside, the Guinness campaign might be forgotten now – or worse, remembered as an overblown blast of hot air dreamed up in some modish ad agency above in Dublin. Instead, Clare came along and changed everything. In the spring of 1995, Clare were very easy to stereotype. These were the days when the league wrapped around Christmas and in the muck and the cold and the drudgery, Clare had a fierceness to them that took advantage of any opposition that fancied a handy afternoon with the summer well off in the distance. A pain in the neck if you met them on a going day in the league but not to be relied upon on the biggest days. They had a recent, ill-starred record in Munster finals to bear that out. Heavy beatings from Tipp and Limerick in 1993 and ’94 were bad enough on their own; piled on decades of hurt going all the way back to their last title in 1932, they were toxic. On the day before the league final, new manager Ger Loughnane outlined what the coming summer would mean to them. “I’d swap everything for a Munster title. The whole lot. My whole hurling life. These fellas today, they have the chance. They can get out there and realise that this is what it is all about, that this is what you play hurling for. They can build on that and win their Munster title. That means so much to us all. They won’t have to look back and regret.” When Clare promptly lost 2-12 to 0-9 to Kilkenny in that league final, you didn’t have many takers for Loughnane’s assertion that this could be the group to turn everything around. Loughnane had been involved in 12 Munster finals as a player and selector at various levels down the years and he’d lost them all. Big talk was fine and dandy but what was there to believe in? Come the Munster championship, Clare were quietly but firmly dismissed by all and sundry. Cashman’s bookies in Cork priced their championship opener thus: Cork 2/5, Clare 9/4. A bar in Ennis had sent the Clare squad a cheque for £250 so they could have a pre-championship drink together. Anthony Daly took it instead and slapped it down on Clare to win the Munster championship at odds of 7/1. Anyone with half an interest in the game knows the rest. Or at least knows bits and pieces of it. That summer was a blazing one, the hottest for decades, and in the mind’s eye Clare’s summer is a jigsaw of sun-scorched fables and legends. Seanie McMahon and his broken collarbone, playing out the last 15 minutes against Cork at corner-forward. Ollie Baker’s bundled goal to win that game in injury-time. Limerick swept aside in the second half of the Munster final. Bonfires across the county on the Monday night. Galway put to the sword in the All-Ireland semi-final. Offaly just squeezed out in the final. Eamonn Taaffe’s goal, whipped to the net with his only touch of the sliotar all summer. Daly’s 65, Johnny Pilkington’s reply just flicking the post and missing. A first Clare All-Ireland senior title since 1914. It was all just so unlikely. After the Cork game, the cars heading home for Clare were stuck in traffic. A group of Cork teenagers stood at the side of the road as they passed, chanting Tipp, Tipp, Tipp – presuming Clare would meet and be beaten by them next day out. The notion that this was the beginning of a golden era, or that these Claremen were about to popularise the sport as never before, would still have felt ludicrous And yet here they were, All-Ireland champions in a year when hurling caught the wider imagination in a way it rarely had up to that point. The Guinness campaign had made its mark and allied to Clare’s rise, the sport was grabbing people again. Not before time. “The game had gone stale,” wrote Jimmy Barry-Murphy in The Irish Times in the run-up to the final. “This All-Ireland was one that game needed very badly. Interest was waning and this was reflected in the attendances at finals. “There was no comparison to football where the arrival of the Ulster counties as major powers generated enormous interest and a new awareness of the game. Clare have had many setbacks but they have kept battling and are now being rewarded. They have done hurling a great service.” The depth and breadth of that service became more and more apparent as the decade wore on. Attendances at the hurling championship matches ballooned. From an aggregate total of 289,281 in 1994, they rose to 543,335 in 1999. There were plenty of factors, of course – more counties with more hope, more matches with the introduction of the back-door, a growing economy, those Guinness ads. But it was Clare’s summer of 1995 that sparked it all. They weren’t a pebble in a pond that caused a few ripples. They were a boulder that landed from the clear blue sky and left a crater on the landscape. Everything changed after ’95. Not forever, just for a while. But for long enough for the game to stretch itself and grab hold of imaginations outside the usual places of worship. On the Monday night they brought Liam MacCarthy home, one of the towns that got a good rattle was Newmarket-On-Fergus. In the bedlam, the home club put up a stage and stuck any living Newmarket man who ever put on a Clare jersey up there as the backdrop while Daly and Loughnane grabbed the mic out front. One unusual face cloistered at the back of the stage was then Wexford manager Liam Griffin. Of the multitude of stories excavated by Denis Walsh for his towering book Hurling: The Revolution Years, maybe that night in Newmarket captured the giddiness of the time the best. Griffin’s father was from Clare and he’d lived there for a time in his early 20s, long enough to play club hurling and get called up to the Clare under-21s. Thus were his bona fides established for an appearance – however reluctant – up on-stage. Griffin had been in charge of Wexford for a year at that point and their summer had ended with a limp exit against Offaly away back in June. By the skin of his teeth, Griffin had survived an attempted county board putsch in the meantime and was almost certainly the only man alive who thought that the riches showering down upon Clare heads could be Wexford’s 12 months later. “Clare came and I thought, ‘This is fantastic,’” Griffin told Walsh. “I thought, ‘Jesus, the team I have are as good as these,’ and I went through them man for man. There’s no way we’re not as good as these guys. Then Clare won the All-Ireland and I went straight to Clare the following morning because I wanted to see the homecoming and now I understand why. I wanted to drive it into my own psyche.” As the speeches finished and the stage began to clear, Loughnane turned and caught Griffin’s eye. “It could be you next year,” he said. Whether he meant it or not, Griffin’s mind was made up already. He drove home convinced that Wexford could reach out and grab some of that for themselves. The next day he rang around and organised training, 51-and-a-half weeks shy of the 1996 All-Ireland final. In a world of endless trees and branches and roots, it’s obviously simplistic to say that Clare’s All-Ireland begat Wexford’s which begat all the rest of it. But what is inarguable is this – in that sun-drenched summer of 1995, everything felt possible.he 1995 Munster Senior Hurling Championship Final was a hurling match played on 9 July 1995 at Semple Stadium, Thurles, County Tipperary. It was contested by Clare and Limerick. Clare claimed their first Munster Championship since 1932 and fourth ever after beating Limerick on a scoreline of 1-17 to 0-11. Clare were leading the game by 1-5 to 0-7 at half time. With the scores at 0-5 to 0-3 in Clare's favour in the first half, Davy Fitzgerald scored from a penalty five minutes before the break, crashing the ball high into the net at the town end before sprinting back to his goal-line. In 2005 this penalty goal came fifth in the Top 20 GAA Moments poll by the Irish public. Clare were captained by Anthony Daly and managed by Ger Loughnane in his first year. Clare had defeated Cork in the semi-final by 2-13 to 3-09 to reach the final, while Limerick had defeated Tipperary by 0-16 to 0-15 in their semi-final. The match was screened live by RTÉ as part of The Sunday Game programme with commentary by Ger Canning and analysis by Éamonn Cregan.July 9 FinalClare 1-17 – 0-11 Limerick J. O'Connor (0-6), P. J. Connell (0-4), D. FitzGerald (1-0), C. Clancy (0-2), S. McMahon (0-1), F. Tuohy (0-1), F. Hegarty (0-1), S. McNamara (0-1), G. O'Loughlin (0-1). Report G. Kirby (0-6), M. Galligan (0-3), P. Heffernan (0-1), F. Carroll (0-1). Referee: J. McDonnell (Tipperary) -

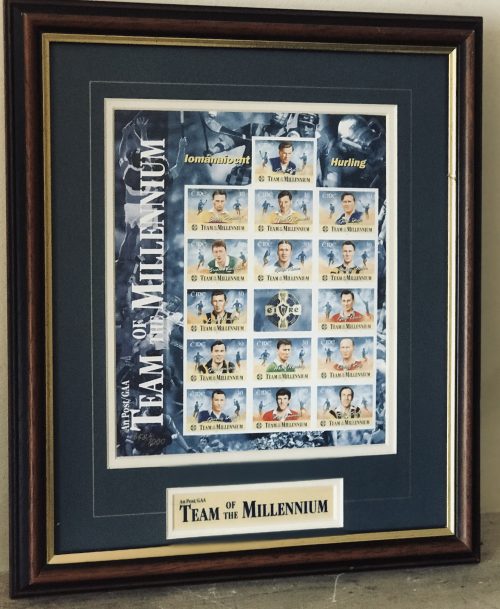

36cm x 29cm The An Post GAA Hurling Team of the Millennium was chosen in 2000 to comprise, as a fifteen-member side divided as one goalkeeper, three full-backs, three half-backs, two midfielders, three half-forwards and three full-forwards, the best hurling team of all-time. The team, announced by GAA President Seán McCague on 24 July 2000 at a special function in Croke Park, was selected by a special committee, comprising five past GAA presidents - Joe McDonagh, Con Murphy, Paddy Buggy, Pat Fanning and Séamus Ó Riain - as well as GAA director-general Liam Mulvihill and four Gaelic games journalists: Paddy Downey, Mick Dunne, Seán Óg Ó Ceallacháin and Jim O'Sullivan. The initiative was sponsored by An Post, who issued special commemorative stamps of the millennium team members.

36cm x 29cm The An Post GAA Hurling Team of the Millennium was chosen in 2000 to comprise, as a fifteen-member side divided as one goalkeeper, three full-backs, three half-backs, two midfielders, three half-forwards and three full-forwards, the best hurling team of all-time. The team, announced by GAA President Seán McCague on 24 July 2000 at a special function in Croke Park, was selected by a special committee, comprising five past GAA presidents - Joe McDonagh, Con Murphy, Paddy Buggy, Pat Fanning and Séamus Ó Riain - as well as GAA director-general Liam Mulvihill and four Gaelic games journalists: Paddy Downey, Mick Dunne, Seán Óg Ó Ceallacháin and Jim O'Sullivan. The initiative was sponsored by An Post, who issued special commemorative stamps of the millennium team members.Controversy

While universal agreement on such a team would prove impossible, the selection committee came in for some criticism regarding omissions and changes from the earlier GAA Hurling Team of the Century. Kilkenny's D. J. Carey was seen as a shock omission from the team. As the holder of a then record seven All-Stars, Carey, whose inter-county career began in 1989, was seen as one of the greatest goal-scorers of his era and was hotly tipped to get one of the half-forward spots for which he was nominated. The 1990s were regarded as a golden age of hurling with many new teams emerging, however, this was not reflected in the team. Clare's Brian Lohan had been tipped for full-back but Wexford's Nick O'Donnell held on. There were no places for any of the Clare team that emerged to win two championships in the nineties. Brian Whelehan was the only player from the previous 20 years to make the team. An absence of players from Galway also sparked off major controversy in that county where the selection committee were accused of belittling the county by not recognising any of its heroes. There was anger too in Wexford over the dropping of full-forward Nicky Rackard from the Team of the Century. Former midfielder Dave Bernie, who won an All-Ireland medal in 1968, when Rackard was a selector, said Wexford fans were stunned by the news he had not been included. -

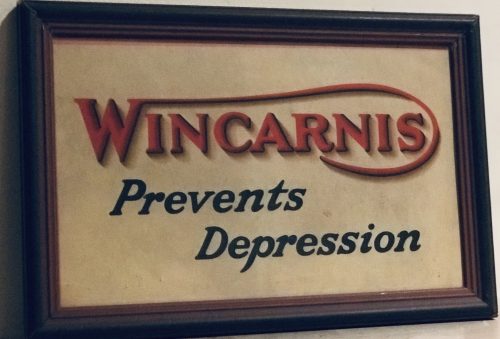

Cool retro ad from the 1970s with a bold and to the point message! Origins : Cork City Dimensions; 21cm x 32cm Glazed First produced in 1887, Wincarnis Tonic Wine is a natural tonic incorporating a unique infusion of herbs and spices. It’s also rich in vitamins, especially energy-giving Vitamin B complex. Usually enjoyed straight, Wincarnis Tonic Wine can also be mixed with gin to make a ‘Gin and Win’. Already a firm favourite in the United Kingdom, its export business continues to grow in Singapore, Malaysia, USA, West Indies and the UAE amongst many other markets.

Cool retro ad from the 1970s with a bold and to the point message! Origins : Cork City Dimensions; 21cm x 32cm Glazed First produced in 1887, Wincarnis Tonic Wine is a natural tonic incorporating a unique infusion of herbs and spices. It’s also rich in vitamins, especially energy-giving Vitamin B complex. Usually enjoyed straight, Wincarnis Tonic Wine can also be mixed with gin to make a ‘Gin and Win’. Already a firm favourite in the United Kingdom, its export business continues to grow in Singapore, Malaysia, USA, West Indies and the UAE amongst many other markets. -

Beautiful print of the original oil by the fascinating Irish artist Letitia Hamilton.This particular painting depicts the Co Wicklow Hunt Point to Point held at Tinahely in the south of the county 27cm x 32cm Baltinglass Co Wicklow The last time the Olympic Games were held in London was in 1948, when they were known as the 'Austerity Games' because of the lean years after World War II. Ireland won one Olympic medal at those games, and amazingly it was not for a sporting feat, but for a discipline no longer regarded as an Olympic competition - art. The one Irish medal-winner was Dunboyne woman Letitia Hamilton, for her painting of a scene at the Meath Hunt Point-to-Point races. What was even more extraordinary was that the painting of horses was not regarded as Hamilton's forte - she was better known for her landscapes, many of which are today part of the Hugh Lane Gallery Collection in Dublin, with other appearing regularly at valuable art auctions. Recently, Ann Hamilton, widow of Letitia's nephew, Major Charles Hamilton of Dunboyne, attended a special celebratory dinner held at Farmleigh House for members of the 1948 Irish Olympic team, where she met many surviving members of their families. The 1948 Games was the last that featured the painting and art category. Letitia Hamilton's winning work was inspired by a country pursuit that was close to her heart. However, the whereabouts of that painting is unknown today. It is believed it may be in private ownership in the United States. Hamilton was one of a family of 10 of Charles Robert Hamilton and Louise Brooke and was known within the family as May. She was born in 1878 at Hamwood, which had been built a century earlier by another Charles Hamilton. Her family had an interesting artistic heritage. Her great-grandmother, Caroline Hamilton, was a professional artist and a distant cousin was the watercolour painter, Rose Barton. These examples may have encouraged her to regard art as a career and may also have inspired her sister, Eva, also an artist. Letitia was educated at Alexandra College, Dublin. Later, she studied at the Metropolitan School of Art where her teacher was Sir William Orpen, the famous Irish portrait painter. She then moved to London and studied with Anne St John Partridge. Afterwards, she went to study in Belgium under Frank Franywayn. In 1924, Letitia travelled to Italy to study with a master in Venice where she spent a year and painted some fine works. She returned to Ireland in 1925. In the years that followed, it was her custom to paint during the summer. During the winter, she worked on the paintings in her studio and in spring she exhibited her work. Her work was exhibited in a number of Dublin Galleries, such as The Dublin Painters' Gallery and the Royal Hibernian Academy. She also exhibited work in many London Galleries, including the Royal Academy and the French Gallery in Berkeley Square. During World War I, she nursed soldiers injured in the fighting. When her brother was appointed governor of St Patrick's Hospital in Dublin, and the associated Woodville in Lucan, now St Edmondsbury treatment centre, she lived at Woodville for a period. Ann Hamilton is in possession of a family scrapbook which includes the letter from AA Longden, art director of the XIVth Olympiad, informing Ms Hamilton that she had won third prize, a bronze medal with diploma, in Section II (a) of the Fine Arts Competition. He wrote: "I wish to congratulate you, on behalf of the committee, and to inform you that your medal and diploma have been handed to the chef to mission of your country for transmission to you. Please inform us when this has been received." The collection also includes a letter from JF Chisholm, the honorary secretary of the Irish Olympic Committee, and the card placed on the piece at the London show, announcing the win. Márin Allen, secretary of the arts section of the OCI , afterwards wrote that "in the painting section, where competition was stiffest and the standard high, Miss Letitia Hamilton, RHA, carried off the Bronze Medal, third place and diploma.....A few weeks ago, at a simple ceremony at the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin, Ireland's victors in the Fine Arts Competitions were presented with their awards by the National Olympic President, Col Eamonn Broy. In an atmosphere of homely friendliness, we talked and looked forward to Helsinki in 1952. On that occasion, Chef de Mission JF Chisholm made a suggestion which might, with advantage, be put into effect: the revival of the Tailteann Games in Ireland." The 1948 Olympic games in London were the first after a forced 12-year break because of World War II. The surviving members of the Irish team remember politics playing a major role in the Irish delegation as well. There were disagreements over whether the team should be a 26 or 32-county one. Part of the delegation was even sent home such was the level of disagreement. There was also an issue over the banner the Irish team was given to march under at the opening ceremony. The organisers gave the Irish team a banner with the word 'Eire' on it. The team manager refused to march under this banner, saying the country was called 'Ireland' and he wanted a banner to reflect this. With just minutes to go, the team capitulated and marched under the Eire banner because of the large number of Irish sports fans in Wembley stadium who had come to see them march in the opening parade. Also in London in 1948, in the literature section, Cavan-born Stanislaus Lynch's 'Echoes of the Hunting Horn' received a diploma. Mr Lynch lived at Tara in latter years and is buried in Skryne. Letitia Hamilton led a very active life until her passing in 1964, continuing to travel abroad. Her sister, Eva, died in 1960, and they are buried in the family burial plot at the Church of Ireland cemetery in Dunboyne.

Beautiful print of the original oil by the fascinating Irish artist Letitia Hamilton.This particular painting depicts the Co Wicklow Hunt Point to Point held at Tinahely in the south of the county 27cm x 32cm Baltinglass Co Wicklow The last time the Olympic Games were held in London was in 1948, when they were known as the 'Austerity Games' because of the lean years after World War II. Ireland won one Olympic medal at those games, and amazingly it was not for a sporting feat, but for a discipline no longer regarded as an Olympic competition - art. The one Irish medal-winner was Dunboyne woman Letitia Hamilton, for her painting of a scene at the Meath Hunt Point-to-Point races. What was even more extraordinary was that the painting of horses was not regarded as Hamilton's forte - she was better known for her landscapes, many of which are today part of the Hugh Lane Gallery Collection in Dublin, with other appearing regularly at valuable art auctions. Recently, Ann Hamilton, widow of Letitia's nephew, Major Charles Hamilton of Dunboyne, attended a special celebratory dinner held at Farmleigh House for members of the 1948 Irish Olympic team, where she met many surviving members of their families. The 1948 Games was the last that featured the painting and art category. Letitia Hamilton's winning work was inspired by a country pursuit that was close to her heart. However, the whereabouts of that painting is unknown today. It is believed it may be in private ownership in the United States. Hamilton was one of a family of 10 of Charles Robert Hamilton and Louise Brooke and was known within the family as May. She was born in 1878 at Hamwood, which had been built a century earlier by another Charles Hamilton. Her family had an interesting artistic heritage. Her great-grandmother, Caroline Hamilton, was a professional artist and a distant cousin was the watercolour painter, Rose Barton. These examples may have encouraged her to regard art as a career and may also have inspired her sister, Eva, also an artist. Letitia was educated at Alexandra College, Dublin. Later, she studied at the Metropolitan School of Art where her teacher was Sir William Orpen, the famous Irish portrait painter. She then moved to London and studied with Anne St John Partridge. Afterwards, she went to study in Belgium under Frank Franywayn. In 1924, Letitia travelled to Italy to study with a master in Venice where she spent a year and painted some fine works. She returned to Ireland in 1925. In the years that followed, it was her custom to paint during the summer. During the winter, she worked on the paintings in her studio and in spring she exhibited her work. Her work was exhibited in a number of Dublin Galleries, such as The Dublin Painters' Gallery and the Royal Hibernian Academy. She also exhibited work in many London Galleries, including the Royal Academy and the French Gallery in Berkeley Square. During World War I, she nursed soldiers injured in the fighting. When her brother was appointed governor of St Patrick's Hospital in Dublin, and the associated Woodville in Lucan, now St Edmondsbury treatment centre, she lived at Woodville for a period. Ann Hamilton is in possession of a family scrapbook which includes the letter from AA Longden, art director of the XIVth Olympiad, informing Ms Hamilton that she had won third prize, a bronze medal with diploma, in Section II (a) of the Fine Arts Competition. He wrote: "I wish to congratulate you, on behalf of the committee, and to inform you that your medal and diploma have been handed to the chef to mission of your country for transmission to you. Please inform us when this has been received." The collection also includes a letter from JF Chisholm, the honorary secretary of the Irish Olympic Committee, and the card placed on the piece at the London show, announcing the win. Márin Allen, secretary of the arts section of the OCI , afterwards wrote that "in the painting section, where competition was stiffest and the standard high, Miss Letitia Hamilton, RHA, carried off the Bronze Medal, third place and diploma.....A few weeks ago, at a simple ceremony at the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin, Ireland's victors in the Fine Arts Competitions were presented with their awards by the National Olympic President, Col Eamonn Broy. In an atmosphere of homely friendliness, we talked and looked forward to Helsinki in 1952. On that occasion, Chef de Mission JF Chisholm made a suggestion which might, with advantage, be put into effect: the revival of the Tailteann Games in Ireland." The 1948 Olympic games in London were the first after a forced 12-year break because of World War II. The surviving members of the Irish team remember politics playing a major role in the Irish delegation as well. There were disagreements over whether the team should be a 26 or 32-county one. Part of the delegation was even sent home such was the level of disagreement. There was also an issue over the banner the Irish team was given to march under at the opening ceremony. The organisers gave the Irish team a banner with the word 'Eire' on it. The team manager refused to march under this banner, saying the country was called 'Ireland' and he wanted a banner to reflect this. With just minutes to go, the team capitulated and marched under the Eire banner because of the large number of Irish sports fans in Wembley stadium who had come to see them march in the opening parade. Also in London in 1948, in the literature section, Cavan-born Stanislaus Lynch's 'Echoes of the Hunting Horn' received a diploma. Mr Lynch lived at Tara in latter years and is buried in Skryne. Letitia Hamilton led a very active life until her passing in 1964, continuing to travel abroad. Her sister, Eva, died in 1960, and they are buried in the family burial plot at the Church of Ireland cemetery in Dunboyne. -

Beautiful print of the original oil by the fascinating Irish artist Letitia Hamilton.This particular painting depicts the Meath Hunt. 30cm x 39cm Dunboyne Co Meath The last time the Olympic Games were held in London was in 1948, when they were known as the 'Austerity Games' because of the lean years after World War II. Ireland won one Olympic medal at those games, and amazingly it was not for a sporting feat, but for a discipline no longer regarded as an Olympic competition - art. The one Irish medal-winner was Dunboyne woman Letitia Hamilton, for her painting of a scene at the Meath Hunt Point-to-Point races. What was even more extraordinary was that the painting of horses was not regarded as Hamilton's forte - she was better known for her landscapes, many of which are today part of the Hugh Lane Gallery Collection in Dublin, with other appearing regularly at valuable art auctions. Recently, Ann Hamilton, widow of Letitia's nephew, Major Charles Hamilton of Dunboyne, attended a special celebratory dinner held at Farmleigh House for members of the 1948 Irish Olympic team, where she met many surviving members of their families. The 1948 Games was the last that featured the painting and art category. Letitia Hamilton's winning work was inspired by a country pursuit that was close to her heart. However, the whereabouts of that painting is unknown today. It is believed it may be in private ownership in the United States. Hamilton was one of a family of 10 of Charles Robert Hamilton and Louise Brooke and was known within the family as May. She was born in 1878 at Hamwood, which had been built a century earlier by another Charles Hamilton. Her family had an interesting artistic heritage. Her great-grandmother, Caroline Hamilton, was a professional artist and a distant cousin was the watercolour painter, Rose Barton. These examples may have encouraged her to regard art as a career and may also have inspired her sister, Eva, also an artist. Letitia was educated at Alexandra College, Dublin. Later, she studied at the Metropolitan School of Art where her teacher was Sir William Orpen, the famous Irish portrait painter. She then moved to London and studied with Anne St John Partridge. Afterwards, she went to study in Belgium under Frank Franywayn. In 1924, Letitia travelled to Italy to study with a master in Venice where she spent a year and painted some fine works. She returned to Ireland in 1925. In the years that followed, it was her custom to paint during the summer. During the winter, she worked on the paintings in her studio and in spring she exhibited her work. Her work was exhibited in a number of Dublin Galleries, such as The Dublin Painters' Gallery and the Royal Hibernian Academy. She also exhibited work in many London Galleries, including the Royal Academy and the French Gallery in Berkeley Square. During World War I, she nursed soldiers injured in the fighting. When her brother was appointed governor of St Patrick's Hospital in Dublin, and the associated Woodville in Lucan, now St Edmondsbury treatment centre, she lived at Woodville for a period. Ann Hamilton is in possession of a family scrapbook which includes the letter from AA Longden, art director of the XIVth Olympiad, informing Ms Hamilton that she had won third prize, a bronze medal with diploma, in Section II (a) of the Fine Arts Competition. He wrote: "I wish to congratulate you, on behalf of the committee, and to inform you that your medal and diploma have been handed to the chef to mission of your country for transmission to you. Please inform us when this has been received." The collection also includes a letter from JF Chisholm, the honorary secretary of the Irish Olympic Committee, and the card placed on the piece at the London show, announcing the win. Márin Allen, secretary of the arts section of the OCI , afterwards wrote that "in the painting section, where competition was stiffest and the standard high, Miss Letitia Hamilton, RHA, carried off the Bronze Medal, third place and diploma.....A few weeks ago, at a simple ceremony at the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin, Ireland's victors in the Fine Arts Competitions were presented with their awards by the National Olympic President, Col Eamonn Broy. In an atmosphere of homely friendliness, we talked and looked forward to Helsinki in 1952. On that occasion, Chef de Mission JF Chisholm made a suggestion which might, with advantage, be put into effect: the revival of the Tailteann Games in Ireland." The 1948 Olympic games in London were the first after a forced 12-year break because of World War II. The surviving members of the Irish team remember politics playing a major role in the Irish delegation as well. There were disagreements over whether the team should be a 26 or 32-county one. Part of the delegation was even sent home such was the level of disagreement. There was also an issue over the banner the Irish team was given to march under at the opening ceremony. The organisers gave the Irish team a banner with the word 'Eire' on it. The team manager refused to march under this banner, saying the country was called 'Ireland' and he wanted a banner to reflect this. With just minutes to go, the team capitulated and marched under the Eire banner because of the large number of Irish sports fans in Wembley stadium who had come to see them march in the opening parade. Also in London in 1948, in the literature section, Cavan-born Stanislaus Lynch's 'Echoes of the Hunting Horn' received a diploma. Mr Lynch lived at Tara in latter years and is buried in Skryne. Letitia Hamilton led a very active life until her passing in 1964, continuing to travel abroad. Her sister, Eva, died in 1960, and they are buried in the family burial plot at the Church of Ireland cemetery in Dunboyne.

Beautiful print of the original oil by the fascinating Irish artist Letitia Hamilton.This particular painting depicts the Meath Hunt. 30cm x 39cm Dunboyne Co Meath The last time the Olympic Games were held in London was in 1948, when they were known as the 'Austerity Games' because of the lean years after World War II. Ireland won one Olympic medal at those games, and amazingly it was not for a sporting feat, but for a discipline no longer regarded as an Olympic competition - art. The one Irish medal-winner was Dunboyne woman Letitia Hamilton, for her painting of a scene at the Meath Hunt Point-to-Point races. What was even more extraordinary was that the painting of horses was not regarded as Hamilton's forte - she was better known for her landscapes, many of which are today part of the Hugh Lane Gallery Collection in Dublin, with other appearing regularly at valuable art auctions. Recently, Ann Hamilton, widow of Letitia's nephew, Major Charles Hamilton of Dunboyne, attended a special celebratory dinner held at Farmleigh House for members of the 1948 Irish Olympic team, where she met many surviving members of their families. The 1948 Games was the last that featured the painting and art category. Letitia Hamilton's winning work was inspired by a country pursuit that was close to her heart. However, the whereabouts of that painting is unknown today. It is believed it may be in private ownership in the United States. Hamilton was one of a family of 10 of Charles Robert Hamilton and Louise Brooke and was known within the family as May. She was born in 1878 at Hamwood, which had been built a century earlier by another Charles Hamilton. Her family had an interesting artistic heritage. Her great-grandmother, Caroline Hamilton, was a professional artist and a distant cousin was the watercolour painter, Rose Barton. These examples may have encouraged her to regard art as a career and may also have inspired her sister, Eva, also an artist. Letitia was educated at Alexandra College, Dublin. Later, she studied at the Metropolitan School of Art where her teacher was Sir William Orpen, the famous Irish portrait painter. She then moved to London and studied with Anne St John Partridge. Afterwards, she went to study in Belgium under Frank Franywayn. In 1924, Letitia travelled to Italy to study with a master in Venice where she spent a year and painted some fine works. She returned to Ireland in 1925. In the years that followed, it was her custom to paint during the summer. During the winter, she worked on the paintings in her studio and in spring she exhibited her work. Her work was exhibited in a number of Dublin Galleries, such as The Dublin Painters' Gallery and the Royal Hibernian Academy. She also exhibited work in many London Galleries, including the Royal Academy and the French Gallery in Berkeley Square. During World War I, she nursed soldiers injured in the fighting. When her brother was appointed governor of St Patrick's Hospital in Dublin, and the associated Woodville in Lucan, now St Edmondsbury treatment centre, she lived at Woodville for a period. Ann Hamilton is in possession of a family scrapbook which includes the letter from AA Longden, art director of the XIVth Olympiad, informing Ms Hamilton that she had won third prize, a bronze medal with diploma, in Section II (a) of the Fine Arts Competition. He wrote: "I wish to congratulate you, on behalf of the committee, and to inform you that your medal and diploma have been handed to the chef to mission of your country for transmission to you. Please inform us when this has been received." The collection also includes a letter from JF Chisholm, the honorary secretary of the Irish Olympic Committee, and the card placed on the piece at the London show, announcing the win. Márin Allen, secretary of the arts section of the OCI , afterwards wrote that "in the painting section, where competition was stiffest and the standard high, Miss Letitia Hamilton, RHA, carried off the Bronze Medal, third place and diploma.....A few weeks ago, at a simple ceremony at the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin, Ireland's victors in the Fine Arts Competitions were presented with their awards by the National Olympic President, Col Eamonn Broy. In an atmosphere of homely friendliness, we talked and looked forward to Helsinki in 1952. On that occasion, Chef de Mission JF Chisholm made a suggestion which might, with advantage, be put into effect: the revival of the Tailteann Games in Ireland." The 1948 Olympic games in London were the first after a forced 12-year break because of World War II. The surviving members of the Irish team remember politics playing a major role in the Irish delegation as well. There were disagreements over whether the team should be a 26 or 32-county one. Part of the delegation was even sent home such was the level of disagreement. There was also an issue over the banner the Irish team was given to march under at the opening ceremony. The organisers gave the Irish team a banner with the word 'Eire' on it. The team manager refused to march under this banner, saying the country was called 'Ireland' and he wanted a banner to reflect this. With just minutes to go, the team capitulated and marched under the Eire banner because of the large number of Irish sports fans in Wembley stadium who had come to see them march in the opening parade. Also in London in 1948, in the literature section, Cavan-born Stanislaus Lynch's 'Echoes of the Hunting Horn' received a diploma. Mr Lynch lived at Tara in latter years and is buried in Skryne. Letitia Hamilton led a very active life until her passing in 1964, continuing to travel abroad. Her sister, Eva, died in 1960, and they are buried in the family burial plot at the Church of Ireland cemetery in Dunboyne. -

19cm x 25cm Ennistymon Co Clare Sometimes its an eclectic or seemingly incongruous picture or photograph that one remembers a certain pub by.This photo hung for years in a public house in Ennistymon,right at the corner of the bar and beside the cash register.There is a strong sense of melancholy and nostalgia about it and here it isn now ,waiting for its next home !

19cm x 25cm Ennistymon Co Clare Sometimes its an eclectic or seemingly incongruous picture or photograph that one remembers a certain pub by.This photo hung for years in a public house in Ennistymon,right at the corner of the bar and beside the cash register.There is a strong sense of melancholy and nostalgia about it and here it isn now ,waiting for its next home ! -

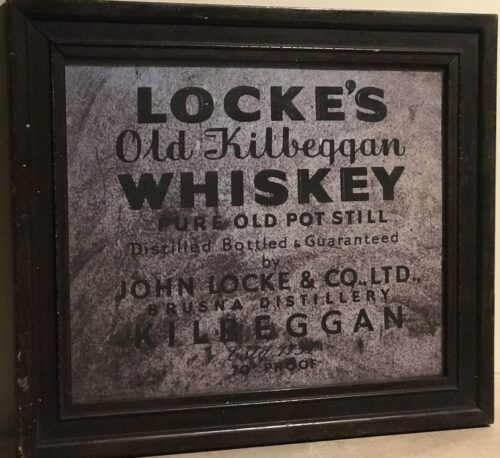

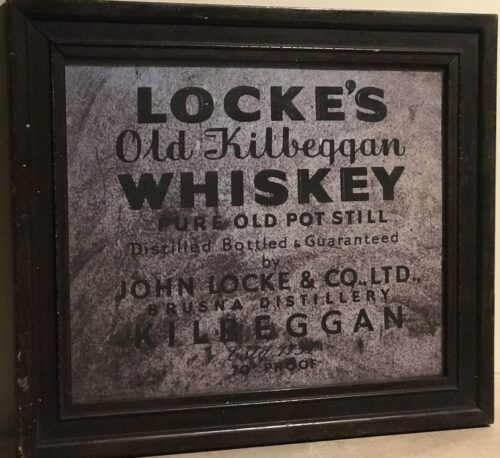

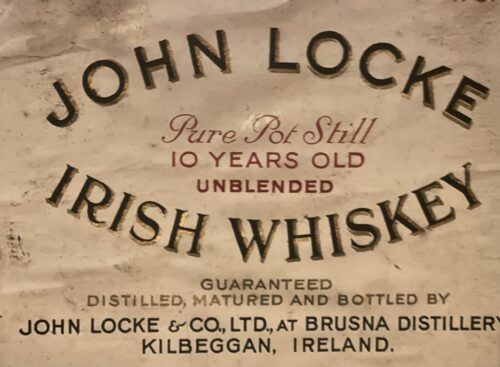

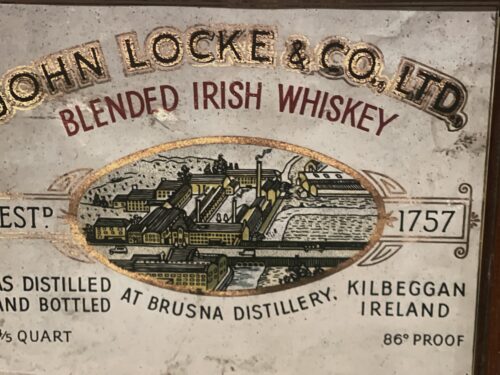

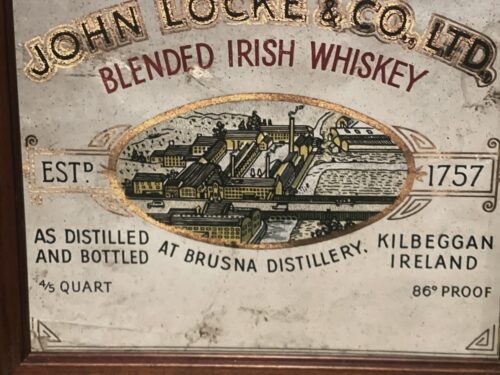

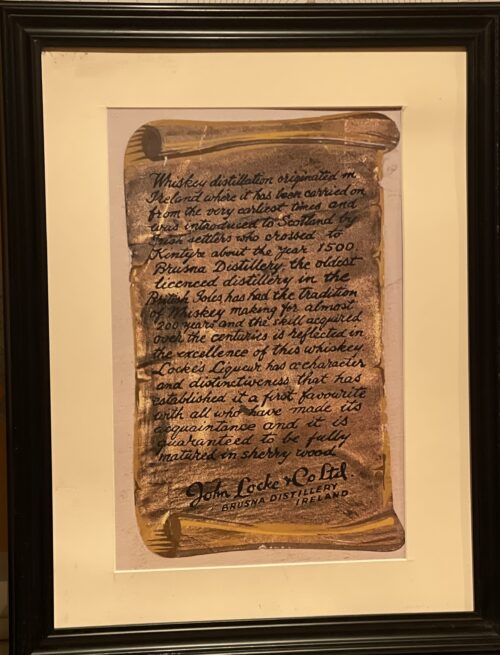

Locke's Old Kilbeggan Pure Pot Still Whiskey Advert Origins: Kilbeggan Co Westmeath Dimensions: 32cm x 37cm The Kilbeggan Distillery (formerly Brusna Distillery and Locke's Distillery) is an Irish whiskey distillery situated on the River Brosna in Kilbeggan, County Westmeath, Ireland. It is owned by Beam Suntory. A small pot still distillery, the licence to distil dates to 1757, a copy of which can be seen in the distillery. Similar to many Irish distilleries, Kilbeggan endured financial difficulties during the early 20th century, and ceased operations in 1957. However, the distillery was later refurbished, with distilling recommencing on-site in 2007. Noted devotees of the distillery's whiskeys include British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill, and Myles na gCopaleen, the Irish playwright.

Locke's Old Kilbeggan Pure Pot Still Whiskey Advert Origins: Kilbeggan Co Westmeath Dimensions: 32cm x 37cm The Kilbeggan Distillery (formerly Brusna Distillery and Locke's Distillery) is an Irish whiskey distillery situated on the River Brosna in Kilbeggan, County Westmeath, Ireland. It is owned by Beam Suntory. A small pot still distillery, the licence to distil dates to 1757, a copy of which can be seen in the distillery. Similar to many Irish distilleries, Kilbeggan endured financial difficulties during the early 20th century, and ceased operations in 1957. However, the distillery was later refurbished, with distilling recommencing on-site in 2007. Noted devotees of the distillery's whiskeys include British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill, and Myles na gCopaleen, the Irish playwright.Early years

The distillery was founded in 1757 by Matthew MacManus, who may have distilled elsewhere before founding Kilbeggan.Although information about the early years of the distillery is scarce, documentation suggests that in its early years the distillery operated with a 232 gallon still, and an annual output of 1,500 gallons. By the early 19th century, the distillery was being run by a John and William Codd. In 1841, the distillery was put up for sale following the dissolution of the partnership between its then owners, William Codd and William Cuffee.The distillery at the time consisted of a brew house, still house with three pot stills (wash still: 8,000 gallons; low wine still, no. 1; 2,000 gallons; low wine still, no. 2: 1,500 gallons), run-room with five receivers, malt house, corn stores capable of storing 5,000 barrels, and oat-meal mills. Also listed in the sale were 400 tonnes of coal, and 10,000 boxes of turf - the latter reflecting the immense quantities of turf consumed at the distillery, so much so, that it was reported to have kept hundreds of poor people profitably employed in cutting, rearing, and drawing it to the town throughout the year.Locke's Distillery

In 1843, the distillery was taken over by John Locke, under whose stewardship the distillery flourished. Locke treated his staff well, and was held in high regard by both his workers and the people of the town. Informal records show that under Locke the distillery provided cottages for its employees, either for rent or purchase through a form of in-house mortgage scheme. In addition, all staff received a wagon load of coal at the start of each winter, the cost of which was deducted from salaries retrospectively on a weekly basis. Testimony of the respect with which he was held is offered by an incident in 1866. Following an accident on-site which had rendered a critical piece of equipment, the steam boiler, inoperable, the distillery had come to a standstill. With Locke unable to afford or obtain a loan to fund a replacement, the future of distillery lay in doubt.However, in a gesture of solidarity, the people of Kilbeggan came together and purchased a replacement boiler, which they presented to John Locke, along with the following public letter of appreciation, which was printed in several local newspapers at the time:An Address from the People of Kilbeggan to John Locke, Esq. Dear Sir - Permit us, your fellow townsmen, to assure of our deep and cordial sympathy in your loss and disappointment from the accident which occurred recently in your Distillery. Sincerely as we regret the accident, happily unattended with loss of life, we cannot but rejoice at the long-wished-for opportunity it affords us of testifying to you the high appreciation in which we hold you for your public and private worth. We are well aware that the restrictions imposed by recent legislation on that particular branch of Irish industry, with which you have been so long identified, have been attended with disastrous results to the trade, as is manifest in the long list of Distilleries now almost in ruins, and which were a few years ago centres of busy industry, affording remunerative employment to thousands of hands; and we are convinced the Kilbeggan Distillery would have long since swelled the dismal catalogue had it fallen into less energetic and enterprising hands. In such an event we would be compelled to witness the disheartening scene of a large number of our working population without employment during that period of the year when employment Is scarcest, and at the same time most essential to the poor. Independent then of what we owe you, on purely personal grounds, we feel we owe you a deep debt of gratitude for maintaining in our midst a manufacture which affords such extensive employment to our poor, and exercises so favourable an influence on the prosperity of the town. In conclusion, dear Sir, we beg your acceptance of a new steam boiler to replace the injured one, as testimony, inadequate though it is, of our unfeigned respect and esteems for you ; and we beg to present it with the ardent wish and earnest hope that, for many long years to come, it may contribute to enhance still more the deservedly high and increasing reputation of the Kilbeggan Distillery.

In a public response to mark the gift, also published in several newspapers, Locke thanked the people of Kilbeggan for their generosity, stating "...I feel this to be the proudest day of my life...". A plaque commemorating the event hangs in the distillery's restaurant today. In 1878, a fire broke out in the "can dip" (sampling) room of the distillery, and spread rapidly. Although, the fire was extinguished within an hour, it destroying a considerable portion of the front of the distillery and caused £400 worth of damage. Hundreds of gallons of new whiskey were also consumed in the blaze - however, the distillery is said to have been saved from further physical and financial ruin through the quick reaction of townsfolk who broke down the doors of the warehouses, and helped roll thousands of casks of ageing spirit down the street to safety. In 1887, the distillery was visited by Alfred Barnard, a British writer, as research for his book, "the Whiskey Distilleries of the United Kingdom". By then, the much enlarged distillery was being managed by John's sons, John Edward and James Harvey, who told Barnard that the distillery's output had more than doubled during the preceding ten years, and that they intended to install electric lighting.Barnard noted that the distillery, which he referred to as the "Brusna Distillery", named for the nearby river, was said to be the oldest in Ireland. According to Barnard, the distillery covered 5 acres, and employed a staff of about 70 men, with the aged and sick pensioned-off or assisted. At the time of his visit, the distillery was producing 157,200 proof gallons per annum, though it had the capacity to produce 200,000. The whiskey, which was sold primarily in Dublin, England, and "the Colonies", was "old pot still", produced using four pot stills (two wash stills: 10,320 / 8,436 gallons; and two spirit stills: 6,170 / 6,080 gallons), which had been installed by Millar and Company, Dublin. Barnard remarked that at the time of his visit over 2,000 casks of spirit were ageing in the distillery's bonded warehouses. In 1893, the distillery ceased to be privately held, and was converted a limited stock company, trading as John Locke & Co., Ltd., with nominal capital of £40,000.Decline and Closure

In the early part of the 20th century, Kilbeggan, like many Irish whiskey distilleries at the time, entered a period of decline. This was due to the combined effects of loss and hampering of market access - due to prohibition in the United States, the trade war with the British Empire, shipping difficulties during the world wars, and Irish Government export quotas; as well as competition from blended Scotch, and disruption to production during the Irish war of Independence. As a result, Kilbeggan was forced to cease production of new spirit for 7 years between 1924 and 1931, decimating the company's cash flow and finances.Most of the staff at the distillery were let go, and the distillery slowly sold off its stocks of aged whiskey. Distilling resumed in 1931, following the end of prohibition in the United States, and for a time the distillery's finances improved - with a loss of £83 in 1931, converted to a modest profit of £6,700 in 1939. In the 1920s, both of John sons passed away, John in 1920, and James in 1927, and ownership of the distillery passed to Locke's granddaughters, Mary Evelyn and Florence Emily.However, by then the distillery was in need to repair, with the turbulent economic conditions of the early 20th century having meant that no investment had been made in new plant since the 1890s. In 1947, the Lockes decided to put the distillery was put up for sale as a going concern. Although run down, the distillery had valuable stocks of mature whiskey, a valuable commodity in post-war Europe.An offer of £305,000 was received from a Swiss investor fronted by an Englishman, going by the name of Horace Smith.Their unstated interest, was not the business itself, but the 60,000 gallons of whiskey stocks, which they hoped to sell on the black market in England at £11 a gallon - thus, more than doubling their investment overnight. However, when they failed to come up with the deposit, the duo were arrested and promptly interrogated by Irish police. The Englishman, it turned out, was an impostor named Maximoe, who was wanted by Scotland Yard.]The Irish authorities placed Maximoe on a ferry back to England for extradition, but he jumped overboard and escaped with the help of unknown accomplices. An Irish opposition politician, Oliver J. Flanagan, subsequently alleged under parliamentary privilege that members of the governing Fianna Fáil political party were linked to the deal, accusing then Irish Taoiseach Éamon de Valera and his son of having accepted gold watches from the Swiss businessman. A tribunal of inquiry discounted the allegations but the damage contributed to Fianna Fáil's defeat in the 1948 election. In addition, as the scandal remained headline news in Ireland for several months, it discouraged interest from other investors in the distillery. Thus with no buyer found, operations continued at the distillery, with production averaging between 120,000 - 150,000 proof gallons per annum, and consumption running at between 15,000 - 20,000 barrels of barrel.In addition, although heavily indebted, investments were made in new plant and equipment. However, the death knell for the distillery came in April 1952, when the Irish Government introduced a 28% hike in the excise duties on spirits, causing a drastic decline in domestic whiskey sales. By November 1953, the distillery could not afford to pay the duty to release whiskey ordered for Christmas from bond, and production was forced to come to a halt. Although distilling had stopped, the firm struggled on until 27 November 1958, when a debenture issued in 1953 fell due, which the distillery could not afford to pay, forcing the bank to call in the receivers. Thus, bringing to an end 201 years of distilling in the town. In 1962, the distillery was purchased for £10,000 by Karl Heinz Moller, a German businessman, who owned a motor distribution company in Hamburg.Moller made a substantial profit on the deal, by selling off the whiskey stocks (about 100,000 gallons - worth tens of thousands of pounds alone) and a rare Mercedes Benz owned by the distillery. Much to the dismay of locals, Moller proceeded to convert the distillery into a pigsty, smashing thousands of Locke earthenware crocks (which would be worth a substantial amount at auction today) to create a hard-core base for the concrete floor. In 1969, the distillery was sold to Powerscreen, a firm which sold Volvo loading shovels, and in the early 1970s, the stills and worms were removed and sold for scrap.Distillery reopens

In 1982, almost thirty years after the distillery ceased operations, the Kilbeggan Preservation and Development Association was formed by locals in the town. Using funds raised locally, the Association restored the Distillery, and reopened it to the public as a whiskey distillery museum. Then, in 1987, the newly opened Cooley Distillery acquired the assets of Kilbeggan distillery, allowing Cooley to relaunch whiskeys under the Kilbeggan and Locke's Whiskey brands. Cooley later also took over the running of the museum, and began the process of re-establishing a working distillery on-site. Cooley were aided in the process by the fact that since the distillery's closure, each subsequent owner had faithfully paid the £5 annual fee to maintain the distilling licence. In 2007, the 250th anniversary of the distillery's founding, distillation recommenced at Kilbeggan. The official firing of the pot stills was witnessed by direct descendants of the three families, the McManuses, the Codds, and the Lockes, who had run the distillery during its 200 year distilling history. In a fitting nod to the long history of distilling at Kilbeggan, one of the two pot stills installed in the refurbished distillery was a 180-year old pot still, which had originally been installed at the Old Tullamore Distillery in the early 1800s.] It is the oldest working pot still producing whiskey in the world today. In 2010, with the installation of a mash tun and fermentation vats, Kilbeggan became a fully operational distillery once again.Present day

Today the distillery is known as Kilbeggan Distillery, and includes a restaurant, The Pantry Restaurant, and a 19th-century waterwheel that has been restored to working condition. The distillery can also be powered by a steam engine, which is in working condition but rarely used. It was installed to allow the distillery to continue operating in times of low water on the river. Prior to the recommencement of operations of Kilbeggan, the three brands associated with the distillery—Kilbeggan, Locke's Blend and Locke's Malt were produced at the Cooley Distillery in County Louth, before being transported to Kilbeggan, where they were to stored in a 200 year old granite warehouse. However, following recommencement of operations at Kilbeggan, new whiskey produced on-site has been sufficiently mature for market since around 2014. Since reopening, the distillery has launched a Kilbeggan Small Batch Rye, the first whiskey to be 100% distilled and matured on-site since the restoration was completed. Double-distilled, the whiskey is produced from a mash of malt, barley, and about 30% rye, said to reflect the traditional practice of using rye, which was common at 19th century Irish distilleries, but has since virtually died out. In late 2009, the distillery released small '3-pack' samples of its still-developing "new make spirit" at 1 month, 1 year, and 2 years of age (in Ireland, the spirit must be aged a minimum of three years before it can legally be called "whiskey"). The distillery's visitor centre was among the nominations in Whisky Magazine's Icons of Whisky visitor attraction category in 2008.Gallery

-

Locke's Old Kilbeggan Pure Pot Still Whiskey Advert Origins: Kilbeggan Co Westmeath Dimensions: 32cm x 37cm The Kilbeggan Distillery (formerly Brusna Distillery and Locke's Distillery) is an Irish whiskey distillery situated on the River Brosna in Kilbeggan, County Westmeath, Ireland. It is owned by Beam Suntory. A small pot still distillery, the licence to distil dates to 1757, a copy of which can be seen in the distillery. Similar to many Irish distilleries, Kilbeggan endured financial difficulties during the early 20th century, and ceased operations in 1957. However, the distillery was later refurbished, with distilling recommencing on-site in 2007. Noted devotees of the distillery's whiskeys include British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill, and Myles na gCopaleen, the Irish playwright.

Locke's Old Kilbeggan Pure Pot Still Whiskey Advert Origins: Kilbeggan Co Westmeath Dimensions: 32cm x 37cm The Kilbeggan Distillery (formerly Brusna Distillery and Locke's Distillery) is an Irish whiskey distillery situated on the River Brosna in Kilbeggan, County Westmeath, Ireland. It is owned by Beam Suntory. A small pot still distillery, the licence to distil dates to 1757, a copy of which can be seen in the distillery. Similar to many Irish distilleries, Kilbeggan endured financial difficulties during the early 20th century, and ceased operations in 1957. However, the distillery was later refurbished, with distilling recommencing on-site in 2007. Noted devotees of the distillery's whiskeys include British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill, and Myles na gCopaleen, the Irish playwright.Early years