68cm x 46cm

The biggest cliché in the collecting world is the “discovery” of a previously unknown cache of stuff that’s been hidden away for years until one day, much to everyone’s amazement, the treasure trove is unearthed and the collecting landscape is changed forever. As a corollary to this hoary trope, if you are in the right place at the right time, you can get in on the action before the word gets out.

“Some of the canvases were 80 years old, dating from 1930.”

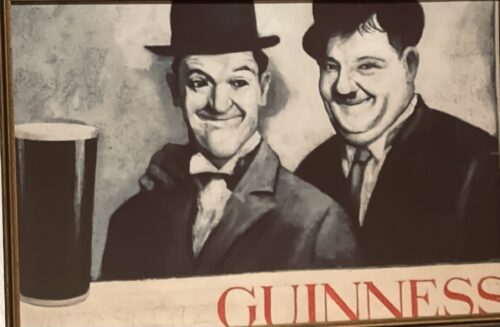

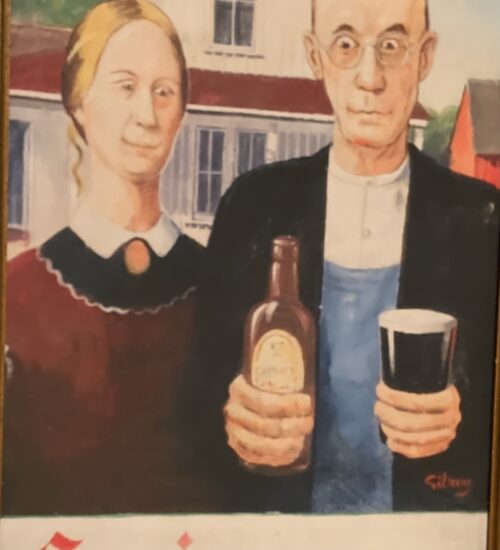

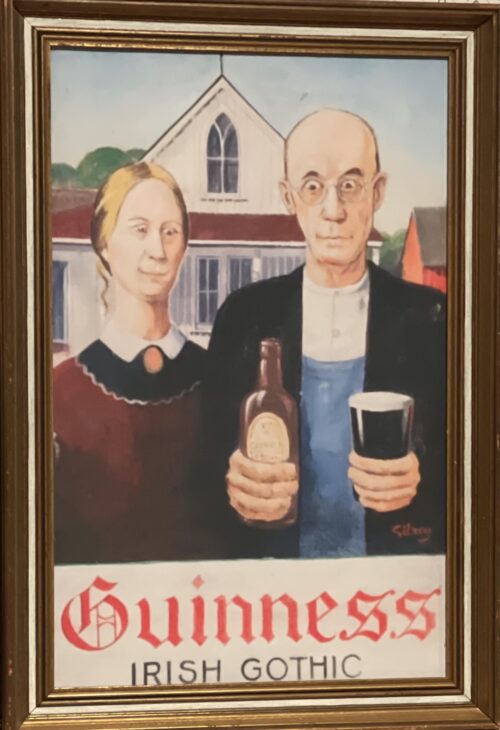

Cliché or not, that’s roughly what happened in 2008 when hundreds of artist John Gilroy’s oil-on-canvas paintings started to appear on the market. The canvases had been painted by Gilroy as final proofs for his iconic Guinness beer posters, the most recognized alcoholic-beverage advertisements of the mid-20th century. Before most collectors of advertising art and breweriana knew what had happened, most of the best pieces had been snapped up by a handful of savvy collectors. In fact, the distribution of the canvases into the hands of private collectors was so swift and stealthy that one prominent member of the Guinness family was forced to get their favorite Gilroys on the secondary market.

One of those early collectors, who wishes to remain anonymous, recalls seeing several canvases for the first time at an antiques show. At first, he thought they were posters since that’s what Guinness collectors have come to expect. But after looking at them more closely, and realizing they were all original paintings, he purchased the lot on the spot. “It was quite exciting to stumble upon what appeared to be the unknown original advertising studies for one of the world’s great brands,” he says. But the casualness of that first encounter would not last, as competition for the newly found canvases ramped up among collectors. Today, the collector describes the scramble for these heretofore-unknown pieces as “a Gilroy art scrum.”

Among those who were particularly interested in the news of the Gilroy cache was David Hughes, who was a brewer at Guinness for 15 years and has written three books on Guinness advertising art and collectibles, the most recent being “Gilroy Was Good for Guinness,” which reproduces more than 150 of the recently “discovered” paintings. Despite being an expert on the cheery ephemera that was created to sell the dark, bitter stout, Hughes, like a lot of people, only learned of the newly uncovered Gilroy canvases as tantalizing examples from the cache (created for markets as diverse as Russia, Israel, France, and the United States) started to surface in 2008.

“Within the Guinness archives itself,” Hughes says of the materials kept at the company’s Dublin headquarters, “they’ve got lots of advertising art, watercolors, and sketches of workups towards the final version of the posters. But they never had a single oil painting. Until the paintings started turning up in the United States, where Guinness memorabilia is quite collectible, it wasn’t fully understood that the posters were based on oils. All of the canvases will be in collections within a year,” Hughes adds. For would-be Gilroy collectors, that means the clock is ticking.

As it turns out, Gilroy’s entire artistic process was a prelude to the oils. “The first thing he’d usually do was a pencil sketch,” says Hughes. “Then he’d paint a watercolor over the top of the pencil sketch to get the color balance right. Once that was settled and all the approvals were in, he’d sit down and paint the oil. The proof version that went to Guinness for approval, it seems, was always an oil painting.”

Based on what we know of John Gilroy’s work as an artist, that makes sense. For almost half a century, Gilroy was regarded not only as one of England’s premier commercial illustrators, but also as one of its best portraitists. “He painted the Queen three times,” says Hughes, “Lord Mountbatten about four times. In 1942, he did a pencil-and-crayon sketch of Churchill in a London bunker.” According to Hughes, Churchill gave that portrait to Russian leader Joseph Stalin at the Yalta Conference with Franklin Delano Roosevelt, which may mean that somewhere in the bowels of the Kremlin, there’s a portrait of Winnie by the same guy who made a living drawing cartoons of flying toucans balancing pints of Guinness on their beaks.

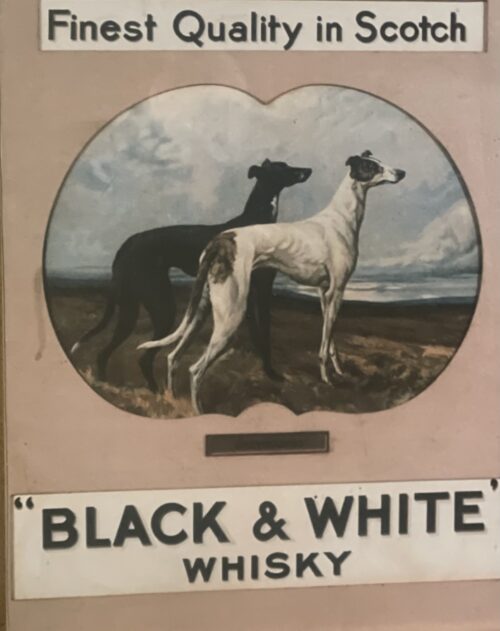

For those who collect advertising art and breweriana, Gilroy is revered for the numerous campaigns he conceived as an illustrator for S.H. Benson, the venerable British ad agency, which was founded in 1893. Though most famous for the Guinness toucan, which has been the internationally recognized mascot of Guinness since 1935, Gilroy’s first campaign with S.H. Benson was for a yeast extract called Bovril. “Do you have Bovril in the U.S.?” Hughes asks. “It’s a rather dark, pungent, savory spread that goes on toast or bread. It’s full of vitamins, quite a traditional product. He also did a lot of work on campaigns for Colman’s mustard and Macleans toothpaste.”

pparently Gilroy’s work caught the eye of Guinness, which wanted something distinctive for its stout. “A black beer is a unique product,” says Hughes. “There weren’t many on the market then, and there are even fewer now. So they wanted their advertising to be well thought of and agreeable to the public.” For example, in the early 1930s, Benson already had an ad featuring a glass of Guinness with a nice foamy head on top. “Gilroy put a smiling face in the foam,” says Hughes. Collectors often refer to this charming drawing as the “anthropomorphic glass.”

That made the black beer friendly. To ensure that it would be appealing to the common man, Benson launched its “Guinness for Strength” campaign, whose most famous image is the 1934 Gilroy illustration of a muscular workman effortlessly balancing an enormous steel girder on one arm and his head.

Another early campaign put Guinness beer in the world of Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.” “Guinness and oysters were a big thing,” says Hughes. In one ad, “Gilroy drew all the oysters from the poem ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’ sipping glasses of Guinness.”

nd then there were the animals, of which the toucan is only the most recognized, and not even the first (that honor goes to a seal). “He had the lion and the ostrich and the bear up the pole,” Hughes says. “There was a whole menagerie of them. The animals kept going for 30 years. It’s probably the longest running campaign in advertising history.”

Most of Gilroy’s animals lived in a zoo, so a central character of the animal advertisements was a zookeeper, who was a caricature of the artist himself. “That’s what Gilroy looked like,” says Hughes. “Gilroy was a chubby, little man with a little moustache. As a younger man, he drew himself into the advert, and he became the zookeeper.”

Gilroy’s animals good-naturedly tormented their zookeeper by stealing his precious Guinness: An ostrich swallows his glass pint whole, whose bulging outline can be seen in its slender throat; a seal balances a pint on its nose; a kangaroo swaps her “joey” for the zookeeper’s brown bottle. Often the zookeeper is so taken aback by these circumstances his hat has popped off his head.

In fact, Gilroy spent a lot of time at the London Zoo to make sure he captured the essence of his animals accurately. “In the archives at Guinness,” says Hughes, “there are a lot of sketches of tortoises, emus, ostriches, and the rest. He perfected the drawing of the animals by going to the zoo, then he adapted them for the adverts.” As a result, a Gilroy bear really looked like a bear, albeit one with a smile on its face.

During World War II, Gilroy’s Guinness ads managed to keep their sense of humor (eg: two sailors painting the hull of an aircraft carrier, each wishing the other was a Guinness), and in the 1950s and early ’60s, Gilroy’s famous pint-toting toucans flew all over the world for Guinness, in front of the Kremlin as well as Mt. Rushmore, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, and the Statue of Liberty, although some of these paintings never made it to the campaign stage.

Gilroy’s work on the Guinness account ended in 1962, and in 1971, Benson was gobbled up by the Madison Avenue advertising firm of Ogilvy & Mather. By then, says Hughes, Gilroy’s work for Guinness was considered the pinnacle of poster design in the U.K., and quite collectible. “The posters were made by a lithographic process. In the 1930s, the canvases were re-created on stone by a print maker, but eventually the paintings were transferred via photolithography onto metal sheets. Some of the biggest posters were made for billboards. Those used 64 different sheets that you’d give to the guy with the bucket of wheat paste and a mop to put up in the right order to create the completed picture.”

In terms of single-sheet posters, Hughes says the biggest ones were probably 4 by 3 feet. Benson’s had an archive of it all, but “when Benson’s shut down in ’71, when they were taken over, they cleaned out their stockroom of hundreds of posters and gave them to the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Today, both have collections of the original posters, including the 64-sheets piled into these packets, which were wrapped in brown paper and tied up with string. They’re extremely difficult to handle; you can’t display them, really.”

At least the paper got a good home. As for the canvases? Well, their history can only be pieced together based on conjecture, but here’s what Hughes thinks he knows.

Sometime in the 1970s, a single collector whose name remains a mystery appears to have purchased as many as 700 to 900 Gilroy paintings that had been in the archives. “The guy who bought the whole archive was an American millionaire,” Hughes says. “He’s a secretive character who doesn’t want to be identified. I don’t blame him. He doesn’t want any publicity about how he bought the collection or its subsequent sale.”

air enough. What we do know for sure is that the years were not kind to Gilroy’s canvases while in storage at Benson’s. In fact, it’s believed that more than half of the cache did not survive the decades and were probably destroyed by the mystery collector who bought them because of their extremely deteriorated condition (torn canvases, images blackened by mildew, etc.). After all, when Gilroy’s canvases were put away, no one at Benson’s thought they’d be regarded in the future as masterpieces.

“A lot of the rolled-up canvases were stuck together,” says Hughes. “Oil takes a long while to dry. Gilroy diluted his oils with what’s called Japan drier, which is a sort of oil thinner that allows you to put the oil on the canvas in a much thinner texture, and then roll them up afterwards. The painted canvas becomes reasonably flexible. The problem is that even with a drier, they still took a long time to dry. And if someone had packed them tightly together and put weight on them, which is what must have happened while the Gilroy paintings were in storage at Benson’s, they’d just stick together. Some of the canvases were 80 years old, dating from 1930.”

For diehard Guinness-advertising fans, though, it’s not all bad news. After all, almost half of the cache was saved, “and it’s beautiful,” says Hughes. “I’ve just come back from Boston to look at a lot of these canvases out there, and they are superb. The guy who’s selling the canvases I saw had about 40 or 50 with him. They’re absolutely fabulous.”

Although he has no proof, Hughes believes the person who bought the cache in the 1970s also oversaw its preservation. Importantly to many collectors, all of the Gilroy canvases are in their found condition, stabilized but essentially unchanged. Even areas in the paint that show evidence of rubbing from adjacent canvases remain as they were found. “I think the preservation has been done by the owner,” Hughes says. “I don’t think the dealers did it. It’s my understanding that they were supplied with fully stabilized canvases from the original buyer. It appears that they were shipped from the U.K., so that’s interesting in itself.” Which suggests they never left the United Kingdom after being purchased by the mysterious American millionaire.

collectors of the approval process at Benson. Gilroy painted his canvases on stretchers, and in the bottom corner of each canvas was a small tag identifying the artist, account code, and action to be taken (“Re-draw,” “Revise,” “Hold,” “Print,” and, during World War II, “Submit to censor”). “They would’ve been shown to Guinness on a wooden stretcher,” Hughes says. “Before they went into storage, somebody removed the stretchers and either laid them flat or rolled them up.”

“As a younger man, he drew himself into the advert, and he became the zookeeper.”

Without exception, the canvases Hughes has seen, which were photographed exclusively for his book, are in fine shape and retain their mounting holes for the stretchers and Benson agency tags. “The colors are good,” he says. “They haven’t been in sunlight. They’ll keep for years and years and years.” One collector notes that you can even see the ruby highlights in Gilroy’s paintings of glasses of the stout. “When a pint of Guinness is backlit by a very strong light, the liquid has a deep ruby color,” this collector says. “Gilroy was very careful to include this effect when he painted beer in clear pint glasses.”

Finally, for Guinness, breweriana, and advertising-art collectors, the Gilroy canvases also offer a peek of what might have been. “I would say about half the images were never commercially used, so they are absolutely brand new, never been seen before,” says Hughes. “They’re going to blow people away.” Of particular interest to collectors in the United States are the Gilroy paintings of classic cars that were created for an aborted, early 1950s campaign to coincide with the brewing of Guinness on Long Island.

Still, it’s the medium that continues to amaze Hughes. “The idea of the canvases, none of us expected that,” he says. “As a Guinness collector, I’ve always collected their adverts, but they’re prints. They never touched Gilroy, he was never anywhere near the printing process. I had acquired a pencil drawing, which I was delighted with. Then these oils started turning up,” he Naturally, Hughes the Guinness scholar has seen a few oils that Hughes the Guinness collector would very much like to own. “If I had a magic wand? Well, I saw one this weekend that I really liked. It’s one of the animal ones. But it’s an animal that was not used commercially. It’s of a rhinoceros sitting on the ground with the zookeeper’s Guinness between his legs. The rhinoceros is looking at the zookeeper, and the zookeeper’s looking around the corner holding his broom. It’s just a great image, and it’s probably the only one of that advert that exists. So if I could wave my magic wand, I think that’s what I’d get. But I’d need $10,000

With those kinds of prices and that kind of buzz, you might think that whoever is handling the Guinness advertising account today might be tempted to just re-run the campaign. But Hughes is realistic about the likelihood of that. “Advertising moves on,” he says. “Gilroy’s jokey, humorous, cartoon-like poster design is quintessentially 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. It is a bit quaint, maybe even a little juvenile for today’s audiences. But it’s still amusing. The other day I showed the draft of my book to my mother, who’s 84. She sat in the kitchen, just giggling at the pictures.”

That sums up Gilroy to Hughes; not that it’s only appealing to people in their 80s, but that his work is ultimately about making people happy, which is why his advertising images connected so honestly with viewers. “Gilroy had a tremendous sense of humor,” Hughes says. “He always saw the funny side of things. He was apparently a chap who, if you were feeling a little down and out, you’d spend a couple of hours with him and he’d just lift your spirits.” You know, in much the same way as a lot of us feel after a nice pint of Guinness.