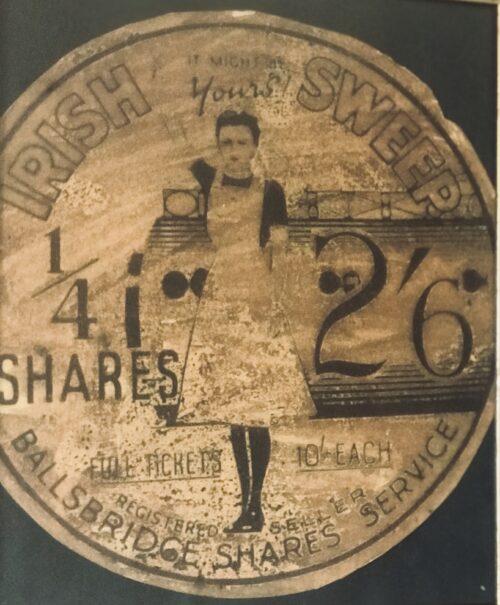

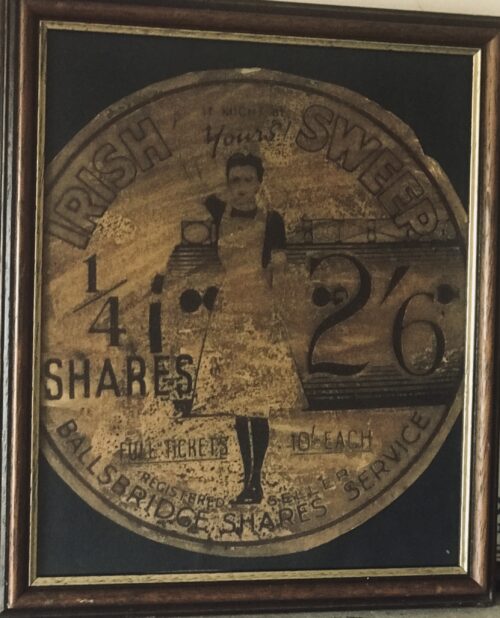

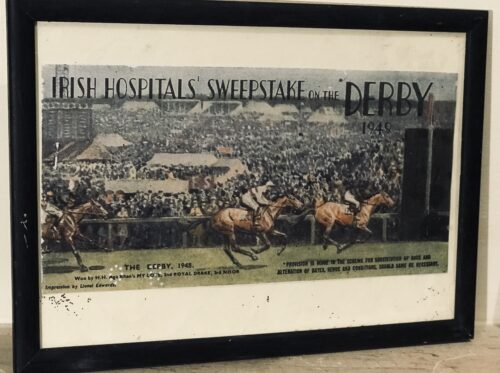

Enlarged ,framed ticket stub for the 1949 Irish Hospital Sweepstake for the Epsom Derby.

Dublin 23cm x 31cm

The Irish Hospital Sweepstake was a lottery established in the

Irish Free State in 1930 as the

Irish Free State Hospitals' Sweepstake to finance hospitals. It is generally referred to as the

Irish Sweepstake, frequently abbreviated to

Irish Sweeps or

Irish Sweep. The Public Charitable Hospitals (Temporary Provisions) Act, 1930 was the act that established the lottery; as this act expired in 1934, in accordance with its terms, the Public Hospitals Acts were the legislative basis for the scheme thereafter. The main organisers were Richard Duggan, Captain Spencer Freeman and

Joe McGrath. Duggan was a well known Dublin

bookmaker who had organised a number of sweepstakes in the decade prior to setting up the Hospitals' Sweepstake. Captain Freeman was a Welsh-born engineer and former captain in the British Army. After the

Constitution of Ireland was enacted in 1937, the name

Irish Hospitals' Sweepstake was adopted.

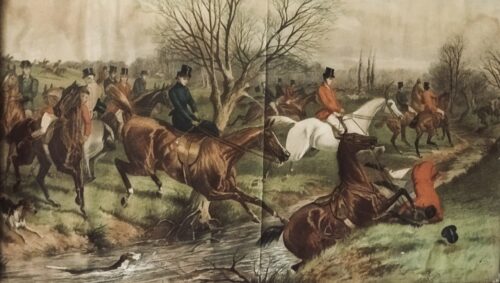

The sweepstake was established because there was a need for investment in hospitals and medical services and the public finances were unable to meet this expense at the time. As the people of Ireland were unable to raise sufficient funds, because of the low population, a significant amount of the funds were raised in the United Kingdom and United States, often among the emigrant Irish. Potentially winning tickets were drawn from rotating drums, usually by nurses in uniform. Each such ticket was assigned to a horse expected to run in one of several

horse races, including the

Cambridgeshire Handicap,

Derby and

Grand National.

Tickets that drew the favourite horses thus stood a higher likelihood of winning and a series of winning horses had to be chosen on the

accumulator system, allowing for enormous prizes.

F. F. Warren, the engineer who designed the mixing drums from which sweepstake tickets were drawn

The original sweepstake draws were held at

The Mansion House, Dublin on 19 May 1939 under the supervision of the Chief Commissioner of Police, and were moved to the more permanent fixture at the

Royal Dublin Society (RDS) in

Ballsbridge later in 1940.

The

Adelaide Hospital in Dublin was the only hospital at the time not to accept money from the Hospitals Trust, as the governors disapproved of sweepstakes.

From the 1960s onwards, revenues declined. The offices were moved to

Lotamore House in Cork. Although giving the appearance of a public charitable lottery, with nurses featured prominently in the advertising and drawings, the Sweepstake was in fact a private for-profit lottery company, and the owners were paid substantial dividends from the profits.

Fortune Magazine described it as "a private company run for profit and its handful of stockholders have used their earnings from the sweepstakes to build a group of industrial enterprises that loom quite large in the modest Irish economy.

Waterford Glass, Irish Glass Bottle Company and many other new Irish companies were financed by money from this enterprise and up to 5,000 people were given jobs."

[3] By his death in 1966,

Joe McGrath had interests in the racing industry, and held the

Renault dealership for Ireland besides large financial and property assets. He was known throughout Ireland for his tough business attitude but also by his generous spirit.At that time, Ireland was still one of the poorer countries in Europe; he believed in investment in Ireland. His home, Cabinteely House, was donated to the state in 1986. The house and the surrounding park are now in the ownership of

Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council who have invested in restoring and maintaining the house and grounds as a public park.

In 1986, the Irish government created a

new public lottery, and the company failed to secure the new contract to manage it. The final sweepstake was held in January 1986 and the company was unsuccessful for a licence bid for the

Irish National Lottery, which was won by

An Post later that year. The company went into voluntary liquidation in March 1987. The majority of workers did not have a pension scheme but the sweepstake had fed many families during lean times and was regarded as a safe job.The Public Hospitals (Amendment) Act, 1990 was enacted for the orderly winding up of the scheme which had by then almost

£500,000 in unclaimed prizes and accrued interest.

A collection of advertising material relating to the Irish Hospitals' Sweepstakes is among the Special Collections of

National Irish Visual Arts Library.

At the time of the Sweepstake's inception, lotteries were generally illegal in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. In the absence of other readily available lotteries, the Irish Sweeps became popular. Even though tickets were illegal outside Ireland, millions were sold in the US and Great Britain. How many of these tickets failed to make it back for the drawing is unknown. The United States Customs Service alone confiscated and destroyed several million

counterfoils from shipments being returned to Ireland.

In the UK, the sweepstakes caused some strain in

Anglo-Irish relations, and the Betting and Lotteries Act 1934 was passed by the parliament of the UK to prevent export and import of lottery related materials.

The

United States Congress had outlawed the use of the

US Postal Service for lottery purposes in 1890. A thriving

black market sprang up for tickets in both jurisdictions.

From the 1950s onwards, as the American, British and Canadian governments relaxed their attitudes towards this form of gambling, and went into the lottery business themselves, the Irish Sweeps, never legal in the United States,

declined in popularity.

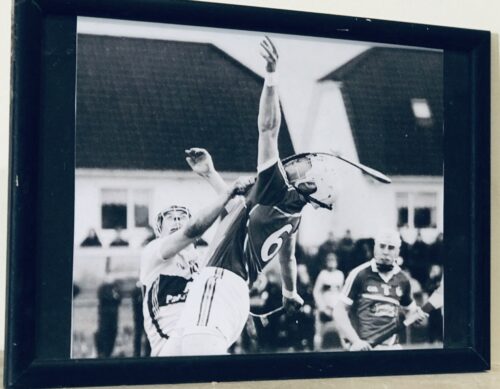

Origins: Co Galway

Dimensions :39cm x 31cm

The Irish Hospitals Sweepstake was established because there was a need for investment in hospitals and medical services and the public finances were unable to meet this expense at the time. As the people of Ireland were unable to raise sufficient funds, because of the low population, a significant amount of the funds were raised in the United Kingdom and United States, often among the emigrant Irish. Potentially winning tickets were drawn from rotating drums, usually by nurses in uniform. Each such ticket was assigned to a horse expected to run in one of several horse races, including the Cambridgeshire Handicap, Derby and Grand National. Tickets that drew the favourite horses thus stood a higher likelihood of winning and a series of winning horses had to be chosen on the accumulator system, allowing for enormous prizes.

F. F. Warren, the engineer who designed the mixing drums from which sweepstake tickets were drawn

The original sweepstake draws were held at

The Mansion House, Dublin on 19 May 1939 under the supervision of the Chief Commissioner of Police, and were moved to the more permanent fixture at the

Royal Dublin Society (RDS) in

Ballsbridge later in 1940.

The

Adelaide Hospital in Dublin was the only hospital at the time not to accept money from the Hospitals Trust, as the governors disapproved of sweepstakes.

From the 1960s onwards, revenues declined. The offices were moved to

Lotamore House in Cork. Although giving the appearance of a public charitable lottery, with nurses featured prominently in the advertising and drawings, the Sweepstake was in fact a private for-profit lottery company, and the owners were paid substantial dividends from the profits.

Fortune Magazine described it as "a private company run for profit and its handful of stockholders have used their earnings from the sweepstakes to build a group of industrial enterprises that loom quite large in the modest Irish economy.

Waterford Glass, Irish Glass Bottle Company and many other new Irish companies were financed by money from this enterprise and up to 5,000 people were given jobs."

By his death in 1966,

Joe McGrath had interests in the racing industry, and held the

Renault dealership for Ireland besides large financial and property assets. He was known throughout Ireland for his tough business attitude but also by his generous spirit. At that time, Ireland was still one of the poorer countries in Europe; he believed in investment in Ireland. His home, Cabinteely House, was donated to the state in 1986. The house and the surrounding park are now in the ownership of

Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council who have invested in restoring and maintaining the house and grounds as a public park.

In 1986, the Irish government created a

new public lottery, and the company failed to secure the new contract to manage it. The final sweepstake was held in January 1986 and the company was unsuccessful for a licence bid for the

Irish National Lottery, which was won by

An Post later that year. The company went into voluntary liquidation in March 1987. The majority of workers did not have a pension scheme but the sweepstake had fed many families during lean times and was regarded as a safe job.The Public Hospitals (Amendment) Act, 1990 was enacted for the orderly winding up of the scheme,

which had by then almost

£500,000 in unclaimed prizes and accrued interest.

A collection of advertising material relating to the Irish Hospitals' Sweepstakes is among the Special Collections of

National Irish Visual Arts Library.

In the United Kingdom and North America[edit]

At the time of the Sweepstake's inception, lotteries were generally illegal in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. In the absence of other readily available lotteries, the Irish Sweeps became popular. Even though tickets were illegal outside Ireland, millions were sold in the US and Great Britain. How many of these tickets failed to make it back for the drawing is unknown. The United States Customs Service alone confiscated and destroyed several million

counterfoils from shipments being returned to Ireland.

In the UK, the sweepstakes caused some strain in

Anglo-Irish relations, and the Betting and Lotteries Act 1934 was passed by the parliament of the UK to prevent export and import of lottery related materials.

[6][7] The

United States Congress had outlawed the use of the

US Postal Service for lottery purposes in 1890. A thriving

black market sprang up for tickets in both jurisdictions.

From the 1950s onwards, as the American, British and Canadian governments relaxed their attitudes towards this form of gambling, and went into the lottery business themselves, the Irish Sweeps, never legal in the United States,

[8]:227 declined in popularity.