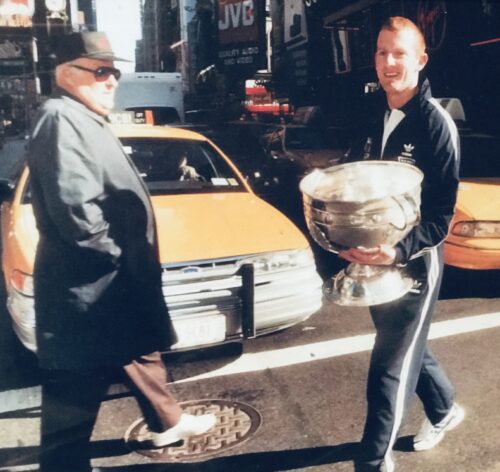

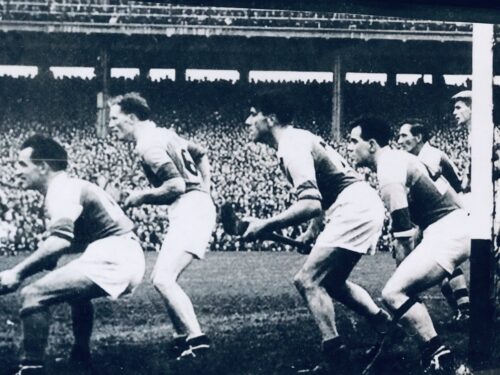

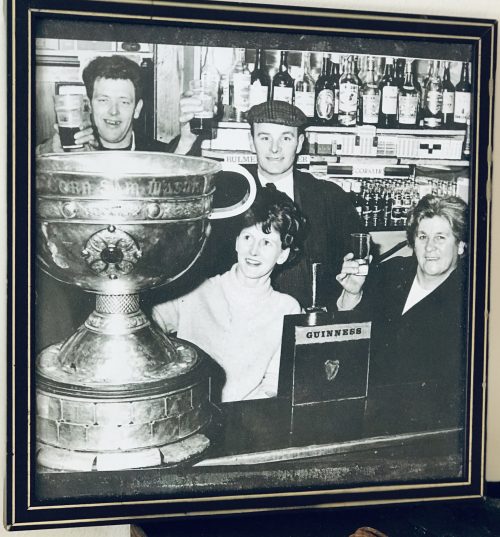

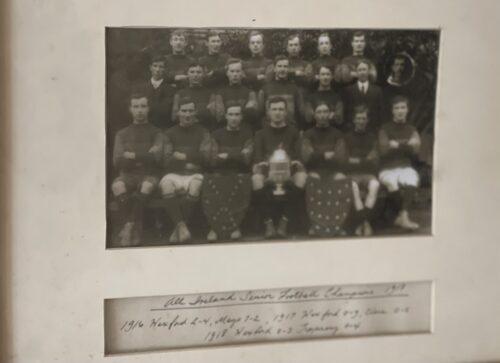

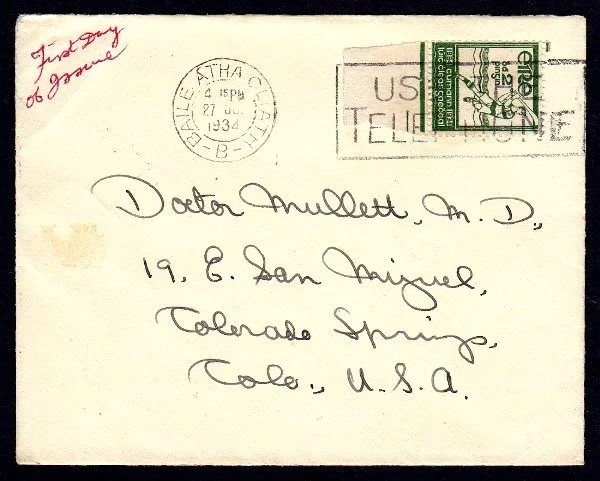

Great piece of Gaelic football Nostalgia here as Meath captain lifts the Sam Maguire on the occasion of the Royal county's first All Ireland Football success in 1949.

Origins: Dunboyne Co Meath Dimensions :26cm x 32cm. Glazed

All-Ireland football final day, 1949. Meath fans are en route to Croke Park by steam train, and will see their county win its first championship. They stop at Dunboyne. He hears their cheers fall through the billowing steam from the railway bridge. Five-year-old Seán Boylan knows something big is stirring.

Then he was simply a small boy kicking a ball around the family garden. The green and gold throng roared encouragement through fellowship and goodwill, buoyed by the occasion.

In later years he would give them good cause to cheer. Just a snapshot, but the moment seems to have acquired a near-cinematic resonance through what it prefigured. That railway bridge is now known locally as Boylan's bridge.

Around Dunboyne, there were local heroes to fire the imagination. His neighbours included Meath players like Jimmy Reilly, Bobby Ruske and 1949 All-Ireland-winning captain Brian Smyth.

"Brian Smyth was a great friend of my father's. I have a memory of kicking a ball around with him in the run-up to the 1954 All-Ireland final.

"He'd call out to the house on a Wednesday night to Daddy, getting the brews. Brian had a very famous dummy and he showed me how to do it. Of course, I practised it and used it all my life after."

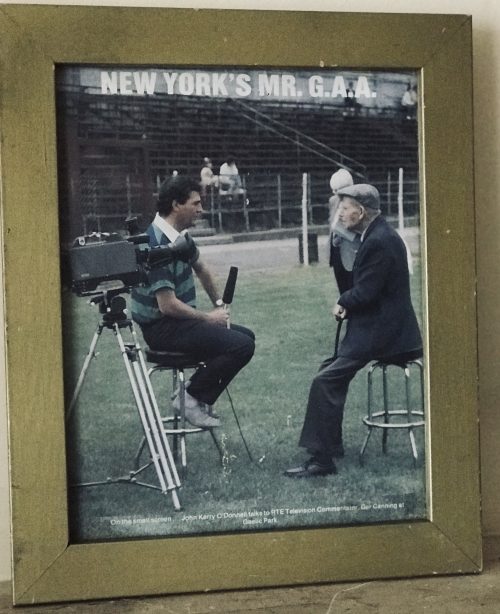

He drew inspiration, too, from further afield. The great Gaelic names of his childhood were lent further mystique by Micheál O'Hehir's radio commentaries, which painted bold pictures in his head.

The legends were remote yet vividly present through the voice piercing the static.

"When he was doing matches you'd swear you were at the game. You were trying to be a John Dowling or a Seán Purcell or a Bobby or Nicky Rackard, a Christy Ring when you heard the way he described it."

Not that Gaelic games alone dominated his formative years. Motor races held in Dunboyne thrilled him as a youngster. Even now, his heart quickens a little at the vroom-vrooming of racing engines.

"I was always mad into motorsport, but most kids around Dunboyne were, because you had the racing which started in the '50s.

"It was outside your door so you followed the motorbikes and the cars. Of course, the only thing you could afford to do yourself was the go-karting. You'd go across to Monasterboice, where there was a track, or down to Askeaton in Limerick. The bug is still there."

At the age of nine, he was sent to Belvedere College. Rugby, of course, was on the sporting curriculum and he played with enthusiasm, once certain positional difficulties had been resolved.

"At the time the Ban was in but I played for a few years. In the first match I played I was put in the secondrow. At my height! I ended up in the backs afterwards, but it was very funny."

He chuckles at the thought of himself as a secondrow forward. In later years he was to meet Peter Stringer after an Ireland international. The scrumhalf greeted him warmly, announcing he was delighted to meet someone even smaller than himself.

His participation in rugby at Belvedere was never questioned, despite his GAA and republican family background. He was left to find his own course.

"My father, Lord be good to him, never tried to influence me in any way with regard to what I would play or what I became involved in. He wasn't that sort of man. And, well, in Belvedere, you're talking about the place where Kevin Barry went to school."

He took two of his boys in to see the old alma mater a few years back and was touched at the reception he received.

"I said I'd see if the then headmaster, Fr Leonard Moloney, was around. I hadn't been back in the place much but he invited us into his office. He went over to the press and took out two Club Lemons and two Mars bars for the lads. From then on that was the only school they wanted to go to and they're there now."

He hurled too at Belvedere, but his education in Gaelic games was to be furthered at Clogher Road Vocational School in Crumlin, which he attended after leaving Belvedere at 15. Moving from the privileged halls of Belvedere to the earthier environment of his new school was a jolt, but football and hurling helped smooth the transition.

In Crumlin, he would learn how to use his hands, within and without the classroom.

"The big thing there was the sport end of it. It was Gaelic and soccer we played. The PE instructor was Jim McCabe, who played centre-half back on the Cavan team that won the All-Ireland in 1952. He was still playing for Cavan at this stage. He was a lovely man and a terrific shooter."

He found himself spending Wednesday afternoons kicking a ball around with McCabe and another Cavan player, Charlie Gallagher. The latter's patiently rigorous application to practising his free-taking left a deep impression on the manager of the future.

While at Clogher Road, he represented Dublin Vocational Schools at centre-half back in both hurling and football. The goalkeeper on the football team was Pat Dunne, who would later play with Manchester United and Ireland.

He was on the move again at 16, switching to Warrenstown Agricultural College near Trim. His family background working with the land made the choice seem logical. Besides, the college did a nice sideline in cultivating footballers and hurlers. Again, he found an All-Ireland-winner circling prominently within his youthful orbit, foreshadowing his own relationship with Sam Maguire.

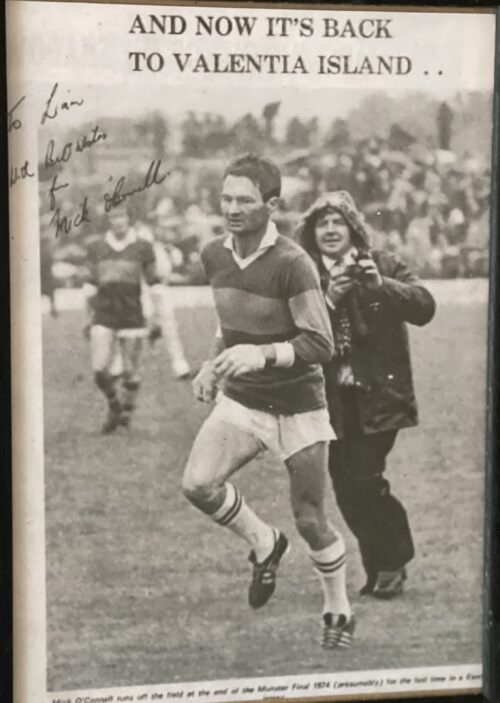

"The man who taught us veterinary was Séamus Murphy, who won five All-Irelands with Kerry in five different positions, an extraordinary record, from corner back to wing-half back to midfield to wing-half forward to corner forward. He brought a few of us from the college to Meath minor football trials."

Hurling, though, was the game at which he was most successful as a player. He broke into the Meath minor hurling panel while at Warrenstown. One day shortly after beginning there, he had another chance encounter which was to echo into the future. He was thumbing a lift home to Dunboyne, hurl slung over a shoulder, only to see a fawn-coloured Ford Anglia pull up. Its driver was Des "Snitchy" Ferguson. Thus began a long association. In later years, his two sons would win All-Irelands with Meath under Boylan's tutelage.

Back in his school days, though, nothing could top the feeling of making the Meath minor hurling panel. "The man who brought me for trials was the famous Brian Smyth. I'll never forget him coming to collect me for the trials. Here I was with Brian Smyth! Then when I got picked for Meath, it was just clover."