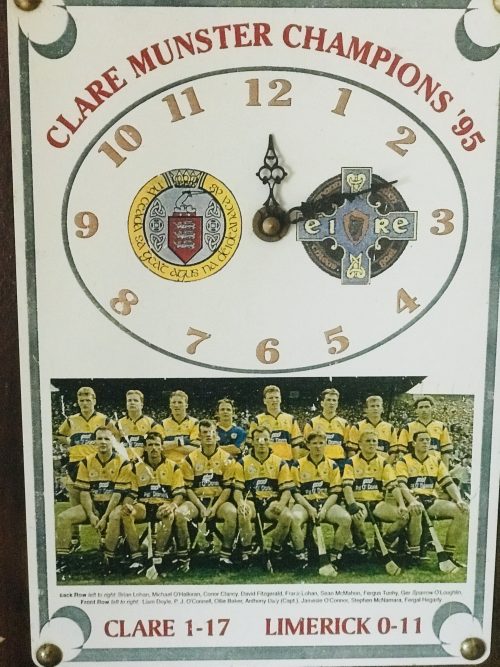

Huge Guinness All Ireland Hurling championship unframed advertisement from the first year of sponsorship in 1995.

38cm wide x 150cm long .

It was not until 1994 that the GAA decided that the football championship would benefit from bringing on a title sponsor in Bank of Ireland. Although an equivalent offer had been on the table for the hurling championship, Central Council pushed the plate away.Though the name of the potential sponsor wasn’t explicitly made public, everyone knew it was Guinness. More to the point, everyone knew why Central Council wouldn’t bite.

As Mulvihill himself noted in his report to Congress, the offer was declined on the basis that “Central Council did not want an alcoholic drinks company associated with a major GAA competition”.

As it turned out, Central Council had been deadlocked on the issue and it was the casting vote of then president

Peter Quinn that put the kibosh on a deal with Guinness. Mulvihill’s disappointment was far from hidden, since he saw the wider damage caused by turning up the GAA nose at Guinness’s advances.

“The unfortunate aspect of the situation,” he wrote, “is that hurling needs support on the promotion of the game much more than football.”

Though it took the point of a bayonet to make them go for it, the GAA submitted in the end and on the day after the league final in 1995 , a three-year partnership with Guinness was announced. The deal would be worth £1 million a year, with half going to the sport and half going to the competition in the shape of marketing.

That last bit was key. Guinness came up with a marketing campaign that fairly scorched across the general consciousness. Billboards screeched out slogans that feel almost corny at this remove but made a huge impact at the same time .

This man can level whole counties in one second flat.

This man can reach speeds of 100mph.

This man can break hearts at 70 yards

Its been Hell for Leather.

Of course, all the marketing in the world can only do so much. Without a story to go alongside, the Guinness campaign might be forgotten now – or worse, remembered as an overblown blast of hot air dreamed up in some modish ad agency above in Dublin.Until the Clare hurlers came along and changed everything."

Malachy Clerkin Irish Times GAA Correspondent

The All Ireland Senior Hurling Championship, known simply as the

All-Ireland Championship, is an annual

inter-county hurling competition organised by the

Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA). It is the highest inter-county hurling competition in

Ireland, and has been contested every year except one since

1887.

The final, currently held on the third Sunday in August, is the culmination of a series of games played during July and August, with the winning team receiving the

Liam MacCarthy Cup. The All-Ireland Championship has always been played on a

straight knockout basis whereby once a team loses they are eliminated from the championship. The qualification procedures for the championship have changed several times throughout its history. Currently, qualification is limited to teams competing in the

Leinster Championship, the

Munster Championship and the two finalists in the

Joe McDonagh Cup.

Twelve teams currently participate in the All-Ireland Championship, with the most successful teams coming from the provinces of

Leinster and

Munster.

Kilkenny,

Cork and

Tipperary are considered "

the big three" of hurling. They have won 94 championships between them.

The title has been won by 13 different teams, 10 of whom have won the title more than once. The all-time record-holders are Kilkenny, who have won the championship on 36 occasions.

Tipperary are the

current champions.

The All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship final was listed in second place by

CNN in its "10 sporting events you have to see live", after the

Olympic Games.

After covering the

1959 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final between

Kilkenny and

Waterford for

BBC Television, English commentator

Kenneth Wolstenholme was moved to describe hurling as his second favourite sport in the world after his first love, soccer.

Alex Ferguson used footage of an All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship final in an attempt to motivate his players during his time as manager of

Premier League soccer outfit

Manchester United; the players winced at the standard of physicality and intensity in which the hurlers were engaged.

Since 1995 the All Ireland Hurling Championship has been sponsored. The sponsor has usually been able to determine the championship's sponsorship name.

Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer

porter in 1778.

The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.

Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export.

“Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.

Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of

Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.”

Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000

barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.

In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount.

Even though Guinness owned no

public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading.

The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician

William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly

Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known

Student’s t-test.

By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees.

By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill.

The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir

John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor

Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market.

In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world.

Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a

Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the

Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.”

Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973.

In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981.

Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used.

In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter.

Guinness acquired the

Distillers Company in 1986.

This led to a

scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case

Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid.

In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo.

The company merged with

Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form

Diageo.

Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.

The Guinness Brewery Park Royal during demolition, at its peak the largest and most productive brewery in the world.

The Guinness brewery in

Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to

St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin.

Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”.

Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts.

The Irish

Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.

This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the

Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the

Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant.

On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the

Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development.

On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.

Two days later, the

Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with

Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate.

Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.

Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997.

In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing

Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use

isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.

This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now.

Guinness

stout is made from water,

barley, roast malt extract,

hops, and

brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is

pasteurisedand

filtered.

Until the late 1950s Guinness was still

racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.

Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of

isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer.

Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians.

Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO

2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO

2 taste. This step was taken after

Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible.

Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the

widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste.

Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an

original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.

Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of

ruby.

The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes.

Studies claim that Guinness can be

beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘

antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful

cholesterol on the artery walls.”

Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by

Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.

Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.”

Origins : Dublin

Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm

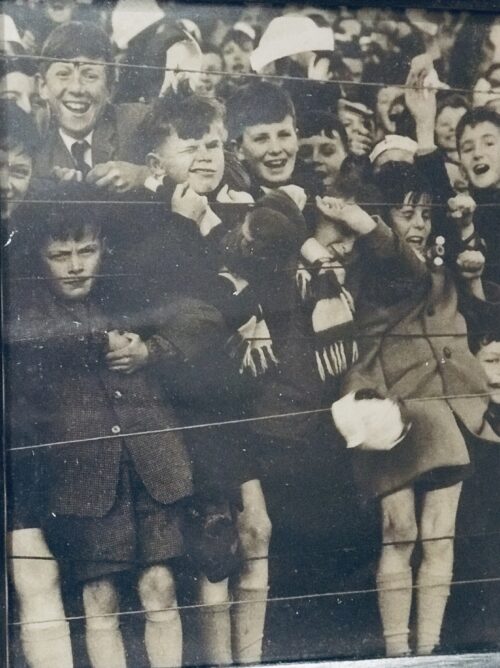

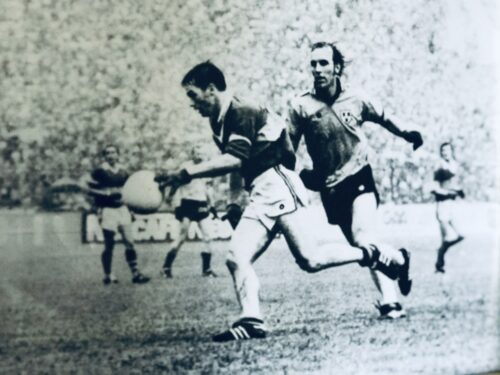

Cork’s Ray Cummins (right) flicking the ball past Clare fullback Jim Power. Cummins goal in the 1977 Munster final turned the match around.

Cork’s Ray Cummins (right) flicking the ball past Clare fullback Jim Power. Cummins goal in the 1977 Munster final turned the match around.

Tom Moloughney, Jimmy Doyle, and Kieran Carey relax in the dressing room after Tipperary’s victory over Dublin in the 1961 All-Ireland final, a success that was to be repeated the following year. Picture from ‘The GAA — A People’s History’

Tom Moloughney, Jimmy Doyle, and Kieran Carey relax in the dressing room after Tipperary’s victory over Dublin in the 1961 All-Ireland final, a success that was to be repeated the following year. Picture from ‘The GAA — A People’s History’

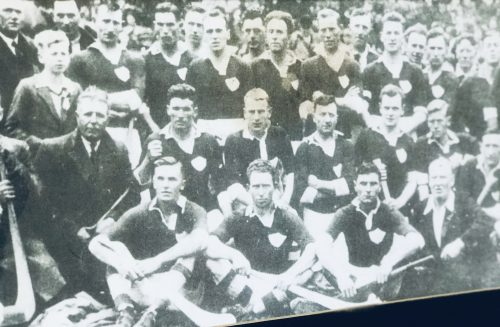

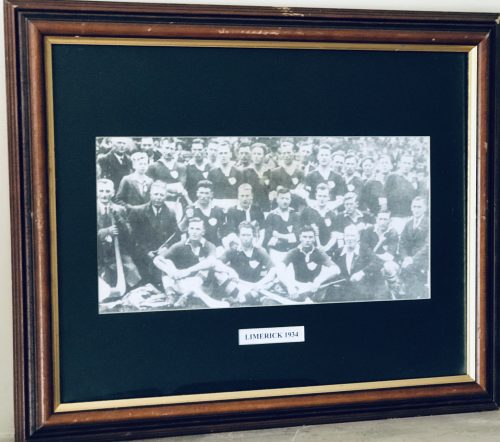

Limerick 5-2 Dublin 2-6

D Clohessy 4-0, M Mackey 1-1, J O’Connell 0-1

Limerick 5-2 Dublin 2-6

D Clohessy 4-0, M Mackey 1-1, J O’Connell 0-1