-

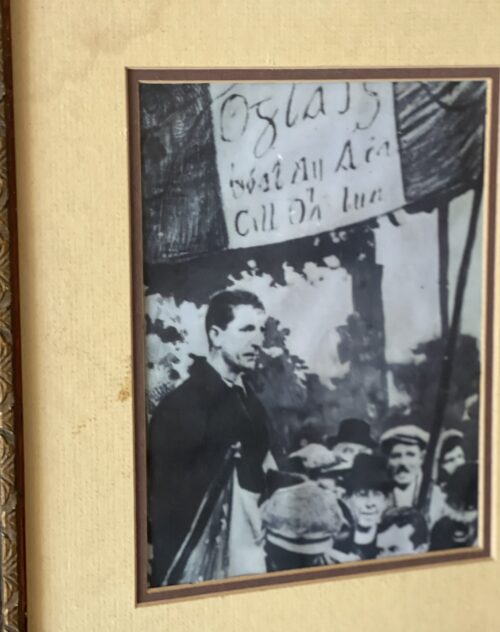

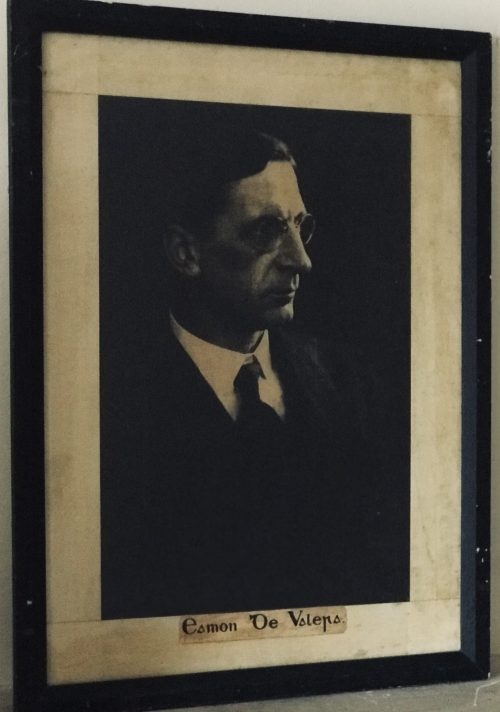

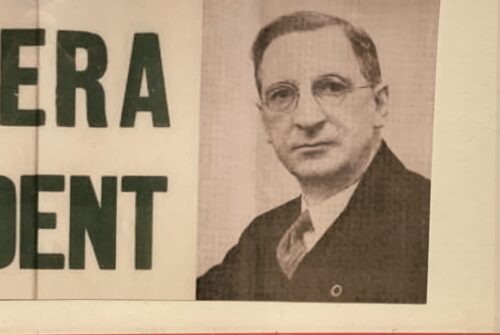

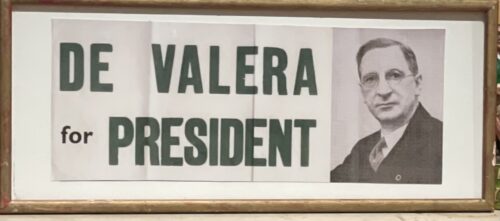

35cm x 45cm. Dublin Extraordinary moment captured in time as a seemingly cordial Eamon De Valera & Michael Collins plus Arthur Griffith and Lord Mayor of Dublin Laurence O'Neill enjoying each others company at Croke Park for the April 6, 1919 Irish Republican Prisoners' Dependents Fund match between Wexford and Tipperary. Staging Gaelic matches for the benefit of the republican prisoners was one of the ways in which the GAA supported the nationalist struggle. How so much would change between those two behemoths of Irish History-Collins and De Valera over the next number of years.

35cm x 45cm. Dublin Extraordinary moment captured in time as a seemingly cordial Eamon De Valera & Michael Collins plus Arthur Griffith and Lord Mayor of Dublin Laurence O'Neill enjoying each others company at Croke Park for the April 6, 1919 Irish Republican Prisoners' Dependents Fund match between Wexford and Tipperary. Staging Gaelic matches for the benefit of the republican prisoners was one of the ways in which the GAA supported the nationalist struggle. How so much would change between those two behemoths of Irish History-Collins and De Valera over the next number of years. -

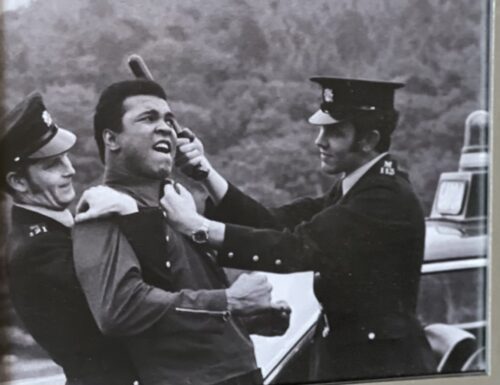

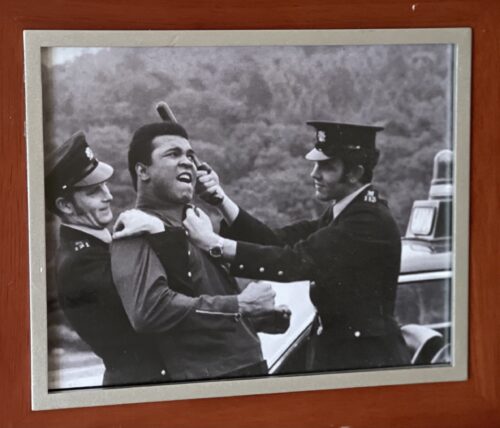

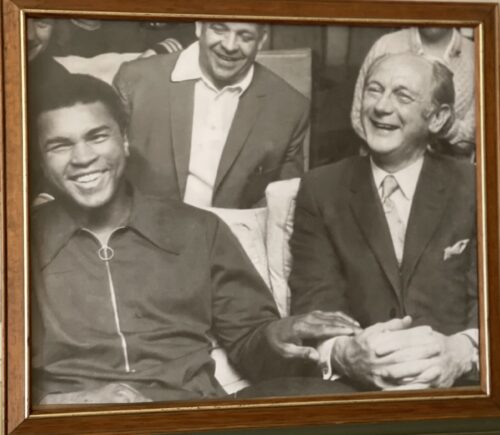

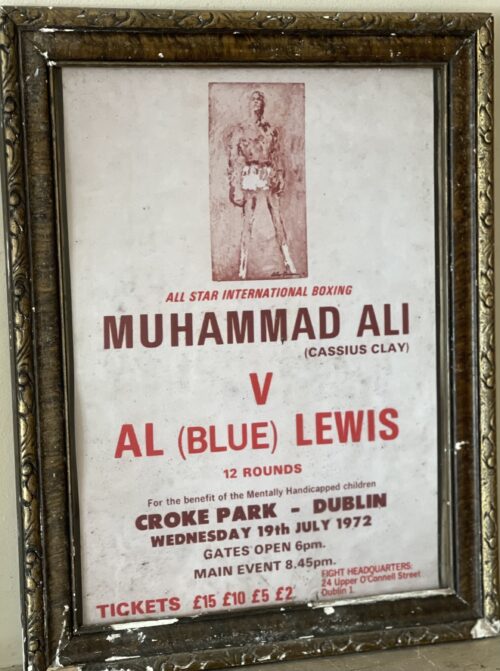

29cm x 36cm. Dublin Famous picture during The Greatest's visit to Ireland of Muhammad Ali play fighting with two members of An Garda Siochana.Some memory for those officers to tell their grandchildren about ! July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.

29cm x 36cm. Dublin Famous picture during The Greatest's visit to Ireland of Muhammad Ali play fighting with two members of An Garda Siochana.Some memory for those officers to tell their grandchildren about ! July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.Muhammad Ali's Irish roots explained

The astonishing fact that he had Irish roots, being descended from Abe Grady, an Irishman from Ennis, County Clare, only became known later in life. He returned to Ireland where he had fought and defeated Al “Blue” Lewis in Croke Park in 1972 almost seven years ago in 2009 to help raise money for his non–profit Muhammad Ali Center, a cultural and educational center in Louisville, Kentucky, and other hospices. He was also there to become the first Freeman of the town. The boxing great is no stranger to Irish shores and previously made a famous trip to Ireland in 1972 when he sat down with Cathal O’Shannon of RTE for a fascinating television interview. What’s more, genealogist Antoinette O'Brien discovered that one of Ali’s great-grandfathers emigrated to the United States from County Clare, meaning that the three-time heavyweight world champion joins the likes of President Obama and Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. as prominent African-Americans with Irish heritage. In the 1860s, Abe Grady left Ennis in County Clare to start a new life in America. He would make his home in Kentucky and marry a free African-American woman. The couple started a family, and one of their daughters was Odessa Lee Grady. Odessa met and married Cassius Clay, Sr. and on January 17, 1942, Cassius junior was born. Cassius Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali when he became a Muslim in 1964. Ali, an Olympic gold medalist at the 1960 games in Rome, has been suffering from Parkinson's for some years but was committed to raising funds for his center During his visit to Clare, he was mobbed by tens of thousands of locals who turned out to meet him and show him the area where his great-grandfather came from.Tracing Muhammad Ali's roots back to County Clare

Historian Dick Eastman had traced Ali’s roots back to Abe Grady the Clare emigrant to Kentucky and the freed slave he married. Eastman wrote: “An 1855 land survey of Ennis, a town in County Clare, Ireland, contains a reference to John Grady, who was renting a house in Turnpike Road in the center of the town. His rent payment was fifteen shillings a month. A few years later, his son Abe Grady immigrated to the United States. He settled in Kentucky." Also, around the year 1855, a man and a woman who were both freed slaves, originally from Liberia, purchased land in or around Duck Lick Creek, Logan, Kentucky. The two married, raised a family and farmed the land. These free blacks went by the name, Morehead, the name of white slave owners of the area. Odessa Grady Clay, Cassius Clay's mother, was the great-granddaughter of the freed slave Tom Morehead and of John Grady of Ennis, whose son Abe had emigrated from Ireland to the United States. She named her son Cassius in honor of a famous Kentucky abolitionist of that time. When he changed his name to Muhammad Ali in 1964, the famous boxer remarked, "Why should I keep my white slavemaster name visible and my black ancestors invisible, unknown, unhonored?" Ali was not only the greatest sporting figure, but he was also the best-known person in the world at his height, revered from Africa to Asia and all over the world. To the end, he was a battler, shown rare courage fighting Parkinson’s Disease, and surviving far longer than most sufferers from the disease. -

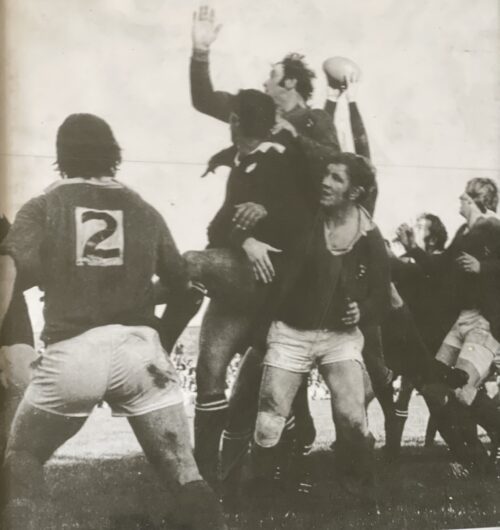

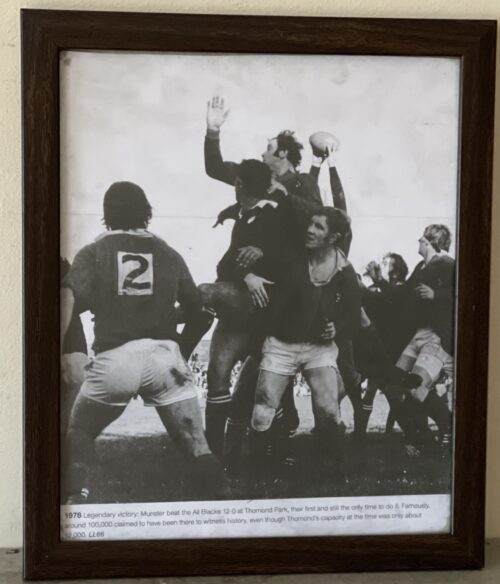

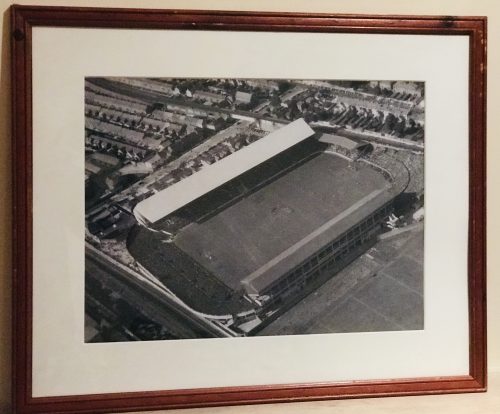

There are many chapters in Munster’s storied rugby journey but pride of place remains the game against the otherwise unbeaten New Zealanders on October 31, 1978. 40cm x 30cm There were some mighty matches between the Kiwis and Munster, most notably at the Mardyke in 1954 when the tourists edged home by 6-3 and again by the same margin at Thomond Park in 1963 while the teams also played a 3-3 draw at Musgrave Park in 1973. During that time, they resisted the best that Ireland, Ulster and Leinster (admittedly with fewer opportunities) could throw at them so this country was still waiting for any team to put one over on the All Blacks when Graham Mourie’s men arrived in Limerick on October 31st, 1978. There is always hope but in truth Munster supporters had little else to encourage them as the fateful day dawned. Whereas the New Zealanders had disposed of Cambridge University, Cardiff, West Wales and London Counties with comparative ease, Munster’s preparations had been confined to a couple of games in London where their level of performance, to put it mildly, was a long way short of what would be required to enjoy even a degree of respectability against the All Blacks. They were hammered by Middlesex County and scraped a draw with London Irish. Ever before those two games, things hadn’t been going according to plan. Tom Kiernan had coached Munster for three seasons in the mid-70s before being appointed Branch President, a role he duly completed at the end of the 1977/78 season. However, when coach Des Barry resigned for personal reasons, Munster turned once again to Kiernan. Being the great Munster man that he was and remains, Tom was happy to oblige although as an extremely shrewd observer of the game, one also suspected that he spotted something special in this group of players that had escaped most peoples’ attention. He refused to be dismayed by what he saw in the games in London, instead regarding them as crucial in the build-up to the All Blacks encounter. He was, in fact, ahead of his time, as he laid his hands on video footage of the All Blacks games, something unheard of back in those days, nor was he averse to the idea of making changes in key positions. A major case in point was the introduction of London Irish loose-head prop Les White of whom little was known in Munster rugby circles but who convinced the coaching team he was the ideal man to fill a troublesome position. Kiernan was also being confronted by many other difficult issues. The team he envisaged taking the field against the tourists was composed of six players (Larry Moloney, Seamus Dennison, Gerry McLoughlin, Pat Whelan, Brendan Foley and Colm Tucker) based in Limerick, four (Greg Barrett, Jimmy Bowen, Moss Finn and Christy Cantillon) in Cork, four more (Donal Canniffe, Tony Ward, Moss Keane and Donal Spring) in Dublin and Les White who, according to Keane, “hailed from somewhere in England, at that time nobody knew where”. Always bearing in mind that the game then was totally amateur and these guys worked for a living, for most people it would have been impossible to bring them all together on a regular basis for six weeks before the match. But the level of respect for Kiernan was so immense that the group would have walked on the proverbial bed of nails for him if he so requested. So they turned up every Wednesday in Fermoy — a kind of halfway house for the guys travelling from three different locations and over appreciable distances. Those sessions helped to forge a wonderful team spirit. After all, guys who had been slogging away at work only a short few hours previously would hardly make that kind of sacrifice unless they meant business. October 31, 1978 dawned wet and windy, prompting hope among the faithful that the conditions would suit Munster who could indulge in their traditional approach sometimes described rather vulgarly as “boot, bite and bollock” and, who knows, with the fanatical Thomond Park crowd cheering them on, anything could happen. Ironically, though, the wind and rain had given way to a clear, blue sky and altogether perfect conditions in good time for the kick-off. Surely, now, that was Munster’s last hope gone — but that didn’t deter more than 12,000 fans from making their way to Thomond Park and somehow finding a spot to view the action. The vantage points included hundreds seated on the 20-foot high boundary wall, others perched on the towering trees immediately outside the ground and some even watched from the windows of houses at the Ballynanty end that have since been demolished. The atmosphere was absolutely electric as the teams took the field, the All Blacks performed the Haka and the Welsh referee Corris Thomas got things under way. The first few skirmishes saw the teams sizing each other up before an incident that was to be recorded in song and story occurred, described here — with just the slightest touch of hyperbole! — by Terry McLean in his book ‘Mourie’s All Blacks’. “In only the fifth minute, Seamus Dennison, him the fellow that bore the number 13 jersey in the centre, was knocked down in a tackle. He came from the Garryowen club which might explain his subsequent actions — to join that club, so it has been said, one must walk barefooted over broken glass, charge naked through searing fires, run the severest gauntlets and, as a final test of manhood, prepare with unfaltering gaze to make a catch of the highest ball ever kicked while aware that at least eight thundering members of your own team are about to knock you down, trample all over you and into the bargain hiss nasty words at you because you forgot to cry out ‘Mark’. Moss Keane recalled the incident: “It was the hardest tackle I have ever seen and lifted the whole team. That was the moment we knew we could win the game.” Kiernan also acknowledged the importance of “The Tackle”.Many years on, Stuart Wilson vividly recalled the Dennison tackles and spoke about them in remarkable detail and with commendable honesty: “The move involved me coming in from the blind side wing and it had been working very well on tour. It was a workable move and it was paying off so we just kept rolling it out. Against Munster, the gap opened up brilliantly as it was supposed to except that there was this little guy called Seamus Dennison sitting there in front of me. “He just basically smacked the living daylights out of me. I dusted myself off and thought, I don’t want to have to do that again. Ten minutes later, we called the same move again thinking we’d change it slightly but, no, it didn’t work and I got hammered again.” The game was 11 minutes old when the most famous try in the history of Munster rugby was scored. Tom Kiernan recalled: “It came from a great piece of anticipation by Bowen who in the first place had to run around his man to get to Ward’s kick ahead. He then beat two men and when finally tackled, managed to keep his balance and deliver the ball to Cantillon who went on to score. All of this was evidence of sharpness on Bowen’s part.” Very soon it would be 9-0. In the first five minutes, a towering garryowen by skipper Canniffe had exposed the vulnerability of the New Zealand rearguard under the high ball. They were to be examined once or twice more but it was from a long range but badly struck penalty attempt by Ward that full-back Brian McKechnie knocked on some 15 yards from his line and close to where Cantillon had touched down a few minutes earlier. You could sense White, Whelan, McLoughlin and co in the front five of the Munster scrum smacking their lips as they settled for the scrum. A quick, straight put-in by Canniffe, a well controlled heel, a smart pass by the scrum-half to Ward and the inevitability of a drop goal. And that’s exactly what happened. The All Blacks enjoyed the majority of forward possession but the harder they tried, the more they fell into the trap set by the wily Kiernan and so brilliantly carried out by every member of the Munster team. The tourists might have edged the line-out contest through Andy Haden and Frank Oliver but scrum-half Mark Donaldson endured a miserable afternoon as the Munster forwards poured through and buried him in the Thomond Park turf. As the minutes passed and the All Blacks became more and more unsure as to what to try next, the Thomond Park hordes chanted “Munster-Munster–Munster” to an ever increasing crescendo until with 12 minutes to go, the noise levels reached deafening proportions. And then ... a deep, probing kick by Ward put Wilson under further pressure. Eventually, he stumbled over the ball as it crossed the line and nervously conceded a five-metre scrum. The Munster heel was disrupted but the ruck was won, Tucker gained possession and slipped a lovely little pass to Ward whose gifted feet and speed of thought enabled him in a twinkle to drop a goal although surrounded by a swarm of black jerseys. So the game entered its final 10 minutes with the All Blacks needing three scores to win and, of course, that was never going to happen. Munster knew this, so, too, did the All Blacks. Stu Wilson admitted as much as he explained his part in Wardy’s second drop goal: “Tony Ward banged it down, it bounced a little bit, jigged here, jigged there, and I stumbled, fell over, and all of a sudden the heat was on me. They were good chasers. A kick is a kick — but if you have lots of good chasers on it, they make bad kicks look good. I looked up and realised — I’m not going to run out of here so I just dotted it down. I wasn’t going to run that ball back out at them because five of those mad guys were coming down the track at me and I’m thinking, I’m being hit by these guys all day and I’m looking after my body, thank you. Of course it was a five-yard scrum and Ward banged over another drop goal. That was it, there was the game”. The final whistle duly sounded with Munster 12 points ahead but the heroes of the hour still had to get off the field and reach the safety of the dressing room. Bodies were embraced, faces were kissed, backs were pummelled, you name it, the gauntlet had to be walked. Even the All Blacks seemed impressed with the sense of joy being released all about them. Andy Haden recalled “the sea of red supporters all over the pitch after the game, you could hardly get off for the wave of celebration that was going on. The whole of Thomond Park glowed in the warmth that someone had put one over on the Blacks.” Controversially, the All Blacks coach, Jack Gleeson (usually a man capable of accepting the good with the bad and who passed away of cancer within 12 months of the tour), in an unguarded (although possibly misunderstood) moment on the following day, let slip his innermost thoughts on the game. “We were up against a team of kamikaze tacklers,” he lamented. “We set out on this tour to play 15-man rugby but if teams were to adopt the Munster approach and do all they could to stop the All Blacks from playing an attacking game, then the tour and the game would suffer.” It was interpreted by the majority of observers as a rare piece of sour grapes from a group who had accepted the defeat in good spirit and it certainly did nothing to diminish Munster respect for the All Blacks and their proud rugby tradition.He said: “Tackling is as integral a part of rugby as is a majestic centre three-quarter break. There were two noteworthy tackles during the match by Seamus Dennison. He was injured in the first and I thought he might have to come off. But he repeated the tackle some minutes later.”“Jack’s comment was made in the context of the game and meant as a compliment,” Haden maintained. “Indeed, it was probably a little suggestion to his own side that perhaps we should imitate their efforts and emulate them in that department.” Tom Kiernan went along with this line of thought: “I thought he was actually paying a compliment to the Munster spirit. Kamikaze pilots were very brave men. That’s what I took out of that. I didn’t think it was a criticism of Munster.” And Stuart Wilson? “It was meant purely as a compliment. We had been travelling through the UK and winning all our games. We were playing a nice, open style. But we had never met a team that could get up in our faces and tackle us off the field. Every time you got the ball, you didn’t get one player tackling you, you got four. Kamikaze means people are willing to die for the cause and that was the way with every Munster man that day. Their strengths were that they were playing for Munster, that they had a home Thomond Park crowd and they took strength from the fact they were playing one of the best teams in the world.” You could rely on Terry McLean (famed New Zealand journalist) to be fair and sporting in his reaction to the Thomond Park defeat. Unlike Kiernan and Haden, he scorned Jack Gleeson’s “kamikaze” comment, stating that “it was a stern, severe criticism which wanted in fairness on two grounds. It did not sufficiently praise the spirit of Munster or the presence within the one team of 15 men who each emerged from the match much larger than life-size. Secondly, it was disingenuous or, more accurately, naive.” “Gleeson thought it sinful that Ward had not once passed the ball. It was worse, he said, that Munster had made aggressive defence the only arm of their attack. Now, what on earth, it could be asked, was Kiernan to do with his team? He held a fine hand with top trumps in Spring, Cantillon, Foley and Whelan in the forwards and Canniffe, Ward, Dennison, Bowen and Moloney in the backs. Tommy Kiernan wasn’t born yesterday. He played to the strength of his team and upon the suspected weaknesses of the All Blacks.” You could hardly be fairer than that – even if Graham Mourie himself in his 1983 autobiography wasn’t far behind when observing: “Munster were just too good. From the first time Stu Wilson was crashed to the ground as he entered the back line to the last time Mark Donaldson was thrown backwards as he ducked around the side of a maul. They were too good.” One of the nicest tributes of all came from a famous New Zealand photographer, Peter Bush. He covered numerous All Black tours, was close friends with most of their players and a canny one when it came to finding the ideal position from which to snap his pictures. He was the guy perched precariously on the pillars at the entrance to the pitch as the celebrations went on and which he described 20 years later in his book ‘Who Said It’s Only a Game?’And Tom Kiernan and Andy Haden, rugby standard bearers of which their respective countries were justifiably proud, saw things in a similar light.“With that, he flung his arms around me and dragged me with him into the shower. I finally managed to disentangle myself and killed the tape. I didn’t mind really because it had been a wonderful day.” Dimensions :47cm x 57cm“I climbed up on a gate at the end of the game to get this photo and in the middle of it all is Moss Keane, one of the great characters of Irish rugby, with an expression of absolute elation. The All Blacks lost 12-0 to a side that played with as much passion as I have ever seen on a rugby field. The great New Zealand prop Gary Knight said to me later: ‘We could have played them for a fortnight and we still wouldn’t have won’. I was doing a little radio piece after the game and got hold of Moss Keane and said ‘Moss, I wonder if ...’ and he said, ‘ho, ho, we beat you bastards’.

There are many chapters in Munster’s storied rugby journey but pride of place remains the game against the otherwise unbeaten New Zealanders on October 31, 1978. 40cm x 30cm There were some mighty matches between the Kiwis and Munster, most notably at the Mardyke in 1954 when the tourists edged home by 6-3 and again by the same margin at Thomond Park in 1963 while the teams also played a 3-3 draw at Musgrave Park in 1973. During that time, they resisted the best that Ireland, Ulster and Leinster (admittedly with fewer opportunities) could throw at them so this country was still waiting for any team to put one over on the All Blacks when Graham Mourie’s men arrived in Limerick on October 31st, 1978. There is always hope but in truth Munster supporters had little else to encourage them as the fateful day dawned. Whereas the New Zealanders had disposed of Cambridge University, Cardiff, West Wales and London Counties with comparative ease, Munster’s preparations had been confined to a couple of games in London where their level of performance, to put it mildly, was a long way short of what would be required to enjoy even a degree of respectability against the All Blacks. They were hammered by Middlesex County and scraped a draw with London Irish. Ever before those two games, things hadn’t been going according to plan. Tom Kiernan had coached Munster for three seasons in the mid-70s before being appointed Branch President, a role he duly completed at the end of the 1977/78 season. However, when coach Des Barry resigned for personal reasons, Munster turned once again to Kiernan. Being the great Munster man that he was and remains, Tom was happy to oblige although as an extremely shrewd observer of the game, one also suspected that he spotted something special in this group of players that had escaped most peoples’ attention. He refused to be dismayed by what he saw in the games in London, instead regarding them as crucial in the build-up to the All Blacks encounter. He was, in fact, ahead of his time, as he laid his hands on video footage of the All Blacks games, something unheard of back in those days, nor was he averse to the idea of making changes in key positions. A major case in point was the introduction of London Irish loose-head prop Les White of whom little was known in Munster rugby circles but who convinced the coaching team he was the ideal man to fill a troublesome position. Kiernan was also being confronted by many other difficult issues. The team he envisaged taking the field against the tourists was composed of six players (Larry Moloney, Seamus Dennison, Gerry McLoughlin, Pat Whelan, Brendan Foley and Colm Tucker) based in Limerick, four (Greg Barrett, Jimmy Bowen, Moss Finn and Christy Cantillon) in Cork, four more (Donal Canniffe, Tony Ward, Moss Keane and Donal Spring) in Dublin and Les White who, according to Keane, “hailed from somewhere in England, at that time nobody knew where”. Always bearing in mind that the game then was totally amateur and these guys worked for a living, for most people it would have been impossible to bring them all together on a regular basis for six weeks before the match. But the level of respect for Kiernan was so immense that the group would have walked on the proverbial bed of nails for him if he so requested. So they turned up every Wednesday in Fermoy — a kind of halfway house for the guys travelling from three different locations and over appreciable distances. Those sessions helped to forge a wonderful team spirit. After all, guys who had been slogging away at work only a short few hours previously would hardly make that kind of sacrifice unless they meant business. October 31, 1978 dawned wet and windy, prompting hope among the faithful that the conditions would suit Munster who could indulge in their traditional approach sometimes described rather vulgarly as “boot, bite and bollock” and, who knows, with the fanatical Thomond Park crowd cheering them on, anything could happen. Ironically, though, the wind and rain had given way to a clear, blue sky and altogether perfect conditions in good time for the kick-off. Surely, now, that was Munster’s last hope gone — but that didn’t deter more than 12,000 fans from making their way to Thomond Park and somehow finding a spot to view the action. The vantage points included hundreds seated on the 20-foot high boundary wall, others perched on the towering trees immediately outside the ground and some even watched from the windows of houses at the Ballynanty end that have since been demolished. The atmosphere was absolutely electric as the teams took the field, the All Blacks performed the Haka and the Welsh referee Corris Thomas got things under way. The first few skirmishes saw the teams sizing each other up before an incident that was to be recorded in song and story occurred, described here — with just the slightest touch of hyperbole! — by Terry McLean in his book ‘Mourie’s All Blacks’. “In only the fifth minute, Seamus Dennison, him the fellow that bore the number 13 jersey in the centre, was knocked down in a tackle. He came from the Garryowen club which might explain his subsequent actions — to join that club, so it has been said, one must walk barefooted over broken glass, charge naked through searing fires, run the severest gauntlets and, as a final test of manhood, prepare with unfaltering gaze to make a catch of the highest ball ever kicked while aware that at least eight thundering members of your own team are about to knock you down, trample all over you and into the bargain hiss nasty words at you because you forgot to cry out ‘Mark’. Moss Keane recalled the incident: “It was the hardest tackle I have ever seen and lifted the whole team. That was the moment we knew we could win the game.” Kiernan also acknowledged the importance of “The Tackle”.Many years on, Stuart Wilson vividly recalled the Dennison tackles and spoke about them in remarkable detail and with commendable honesty: “The move involved me coming in from the blind side wing and it had been working very well on tour. It was a workable move and it was paying off so we just kept rolling it out. Against Munster, the gap opened up brilliantly as it was supposed to except that there was this little guy called Seamus Dennison sitting there in front of me. “He just basically smacked the living daylights out of me. I dusted myself off and thought, I don’t want to have to do that again. Ten minutes later, we called the same move again thinking we’d change it slightly but, no, it didn’t work and I got hammered again.” The game was 11 minutes old when the most famous try in the history of Munster rugby was scored. Tom Kiernan recalled: “It came from a great piece of anticipation by Bowen who in the first place had to run around his man to get to Ward’s kick ahead. He then beat two men and when finally tackled, managed to keep his balance and deliver the ball to Cantillon who went on to score. All of this was evidence of sharpness on Bowen’s part.” Very soon it would be 9-0. In the first five minutes, a towering garryowen by skipper Canniffe had exposed the vulnerability of the New Zealand rearguard under the high ball. They were to be examined once or twice more but it was from a long range but badly struck penalty attempt by Ward that full-back Brian McKechnie knocked on some 15 yards from his line and close to where Cantillon had touched down a few minutes earlier. You could sense White, Whelan, McLoughlin and co in the front five of the Munster scrum smacking their lips as they settled for the scrum. A quick, straight put-in by Canniffe, a well controlled heel, a smart pass by the scrum-half to Ward and the inevitability of a drop goal. And that’s exactly what happened. The All Blacks enjoyed the majority of forward possession but the harder they tried, the more they fell into the trap set by the wily Kiernan and so brilliantly carried out by every member of the Munster team. The tourists might have edged the line-out contest through Andy Haden and Frank Oliver but scrum-half Mark Donaldson endured a miserable afternoon as the Munster forwards poured through and buried him in the Thomond Park turf. As the minutes passed and the All Blacks became more and more unsure as to what to try next, the Thomond Park hordes chanted “Munster-Munster–Munster” to an ever increasing crescendo until with 12 minutes to go, the noise levels reached deafening proportions. And then ... a deep, probing kick by Ward put Wilson under further pressure. Eventually, he stumbled over the ball as it crossed the line and nervously conceded a five-metre scrum. The Munster heel was disrupted but the ruck was won, Tucker gained possession and slipped a lovely little pass to Ward whose gifted feet and speed of thought enabled him in a twinkle to drop a goal although surrounded by a swarm of black jerseys. So the game entered its final 10 minutes with the All Blacks needing three scores to win and, of course, that was never going to happen. Munster knew this, so, too, did the All Blacks. Stu Wilson admitted as much as he explained his part in Wardy’s second drop goal: “Tony Ward banged it down, it bounced a little bit, jigged here, jigged there, and I stumbled, fell over, and all of a sudden the heat was on me. They were good chasers. A kick is a kick — but if you have lots of good chasers on it, they make bad kicks look good. I looked up and realised — I’m not going to run out of here so I just dotted it down. I wasn’t going to run that ball back out at them because five of those mad guys were coming down the track at me and I’m thinking, I’m being hit by these guys all day and I’m looking after my body, thank you. Of course it was a five-yard scrum and Ward banged over another drop goal. That was it, there was the game”. The final whistle duly sounded with Munster 12 points ahead but the heroes of the hour still had to get off the field and reach the safety of the dressing room. Bodies were embraced, faces were kissed, backs were pummelled, you name it, the gauntlet had to be walked. Even the All Blacks seemed impressed with the sense of joy being released all about them. Andy Haden recalled “the sea of red supporters all over the pitch after the game, you could hardly get off for the wave of celebration that was going on. The whole of Thomond Park glowed in the warmth that someone had put one over on the Blacks.” Controversially, the All Blacks coach, Jack Gleeson (usually a man capable of accepting the good with the bad and who passed away of cancer within 12 months of the tour), in an unguarded (although possibly misunderstood) moment on the following day, let slip his innermost thoughts on the game. “We were up against a team of kamikaze tacklers,” he lamented. “We set out on this tour to play 15-man rugby but if teams were to adopt the Munster approach and do all they could to stop the All Blacks from playing an attacking game, then the tour and the game would suffer.” It was interpreted by the majority of observers as a rare piece of sour grapes from a group who had accepted the defeat in good spirit and it certainly did nothing to diminish Munster respect for the All Blacks and their proud rugby tradition.He said: “Tackling is as integral a part of rugby as is a majestic centre three-quarter break. There were two noteworthy tackles during the match by Seamus Dennison. He was injured in the first and I thought he might have to come off. But he repeated the tackle some minutes later.”“Jack’s comment was made in the context of the game and meant as a compliment,” Haden maintained. “Indeed, it was probably a little suggestion to his own side that perhaps we should imitate their efforts and emulate them in that department.” Tom Kiernan went along with this line of thought: “I thought he was actually paying a compliment to the Munster spirit. Kamikaze pilots were very brave men. That’s what I took out of that. I didn’t think it was a criticism of Munster.” And Stuart Wilson? “It was meant purely as a compliment. We had been travelling through the UK and winning all our games. We were playing a nice, open style. But we had never met a team that could get up in our faces and tackle us off the field. Every time you got the ball, you didn’t get one player tackling you, you got four. Kamikaze means people are willing to die for the cause and that was the way with every Munster man that day. Their strengths were that they were playing for Munster, that they had a home Thomond Park crowd and they took strength from the fact they were playing one of the best teams in the world.” You could rely on Terry McLean (famed New Zealand journalist) to be fair and sporting in his reaction to the Thomond Park defeat. Unlike Kiernan and Haden, he scorned Jack Gleeson’s “kamikaze” comment, stating that “it was a stern, severe criticism which wanted in fairness on two grounds. It did not sufficiently praise the spirit of Munster or the presence within the one team of 15 men who each emerged from the match much larger than life-size. Secondly, it was disingenuous or, more accurately, naive.” “Gleeson thought it sinful that Ward had not once passed the ball. It was worse, he said, that Munster had made aggressive defence the only arm of their attack. Now, what on earth, it could be asked, was Kiernan to do with his team? He held a fine hand with top trumps in Spring, Cantillon, Foley and Whelan in the forwards and Canniffe, Ward, Dennison, Bowen and Moloney in the backs. Tommy Kiernan wasn’t born yesterday. He played to the strength of his team and upon the suspected weaknesses of the All Blacks.” You could hardly be fairer than that – even if Graham Mourie himself in his 1983 autobiography wasn’t far behind when observing: “Munster were just too good. From the first time Stu Wilson was crashed to the ground as he entered the back line to the last time Mark Donaldson was thrown backwards as he ducked around the side of a maul. They were too good.” One of the nicest tributes of all came from a famous New Zealand photographer, Peter Bush. He covered numerous All Black tours, was close friends with most of their players and a canny one when it came to finding the ideal position from which to snap his pictures. He was the guy perched precariously on the pillars at the entrance to the pitch as the celebrations went on and which he described 20 years later in his book ‘Who Said It’s Only a Game?’And Tom Kiernan and Andy Haden, rugby standard bearers of which their respective countries were justifiably proud, saw things in a similar light.“With that, he flung his arms around me and dragged me with him into the shower. I finally managed to disentangle myself and killed the tape. I didn’t mind really because it had been a wonderful day.” Dimensions :47cm x 57cm“I climbed up on a gate at the end of the game to get this photo and in the middle of it all is Moss Keane, one of the great characters of Irish rugby, with an expression of absolute elation. The All Blacks lost 12-0 to a side that played with as much passion as I have ever seen on a rugby field. The great New Zealand prop Gary Knight said to me later: ‘We could have played them for a fortnight and we still wouldn’t have won’. I was doing a little radio piece after the game and got hold of Moss Keane and said ‘Moss, I wonder if ...’ and he said, ‘ho, ho, we beat you bastards’. -

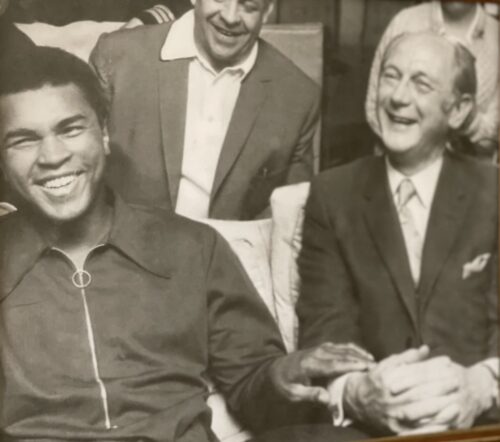

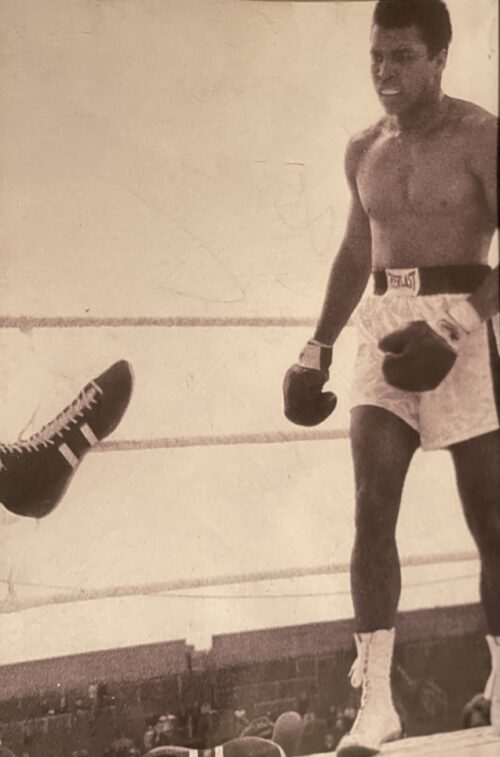

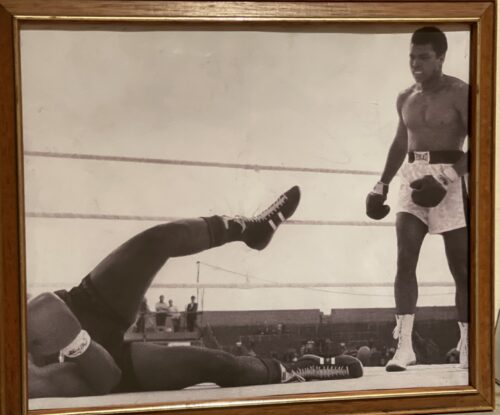

40cm x 34cm July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.

40cm x 34cm July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.Muhammad Ali's Irish roots explained

The astonishing fact that he had Irish roots, being descended from Abe Grady, an Irishman from Ennis, County Clare, only became known later in life. He returned to Ireland where he had fought and defeated Al “Blue” Lewis in Croke Park in 1972 almost seven years ago in 2009 to help raise money for his non–profit Muhammad Ali Center, a cultural and educational center in Louisville, Kentucky, and other hospices. He was also there to become the first Freeman of the town. The boxing great is no stranger to Irish shores and previously made a famous trip to Ireland in 1972 when he sat down with Cathal O’Shannon of RTE for a fascinating television interview. What’s more, genealogist Antoinette O'Brien discovered that one of Ali’s great-grandfathers emigrated to the United States from County Clare, meaning that the three-time heavyweight world champion joins the likes of President Obama and Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. as prominent African-Americans with Irish heritage. In the 1860s, Abe Grady left Ennis in County Clare to start a new life in America. He would make his home in Kentucky and marry a free African-American woman. The couple started a family, and one of their daughters was Odessa Lee Grady. Odessa met and married Cassius Clay, Sr. and on January 17, 1942, Cassius junior was born. Cassius Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali when he became a Muslim in 1964. Ali, an Olympic gold medalist at the 1960 games in Rome, has been suffering from Parkinson's for some years but was committed to raising funds for his center During his visit to Clare, he was mobbed by tens of thousands of locals who turned out to meet him and show him the area where his great-grandfather came from.Tracing Muhammad Ali's roots back to County Clare

Historian Dick Eastman had traced Ali’s roots back to Abe Grady the Clare emigrant to Kentucky and the freed slave he married. Eastman wrote: “An 1855 land survey of Ennis, a town in County Clare, Ireland, contains a reference to John Grady, who was renting a house in Turnpike Road in the center of the town. His rent payment was fifteen shillings a month. A few years later, his son Abe Grady immigrated to the United States. He settled in Kentucky." Also, around the year 1855, a man and a woman who were both freed slaves, originally from Liberia, purchased land in or around Duck Lick Creek, Logan, Kentucky. The two married, raised a family and farmed the land. These free blacks went by the name, Morehead, the name of white slave owners of the area. Odessa Grady Clay, Cassius Clay's mother, was the great-granddaughter of the freed slave Tom Morehead and of John Grady of Ennis, whose son Abe had emigrated from Ireland to the United States. She named her son Cassius in honor of a famous Kentucky abolitionist of that time. When he changed his name to Muhammad Ali in 1964, the famous boxer remarked, "Why should I keep my white slavemaster name visible and my black ancestors invisible, unknown, unhonored?" Ali was not only the greatest sporting figure, but he was also the best-known person in the world at his height, revered from Africa to Asia and all over the world. To the end, he was a battler, shown rare courage fighting Parkinson’s Disease, and surviving far longer than most sufferers from the disease.

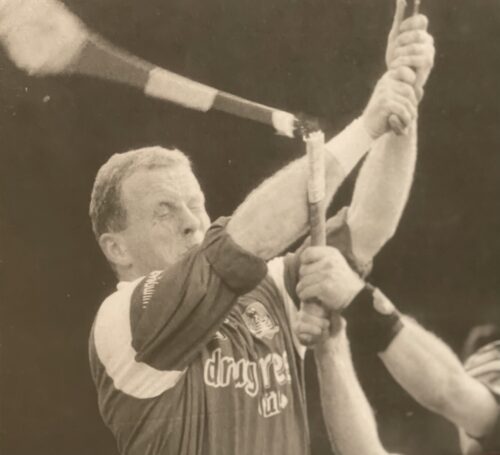

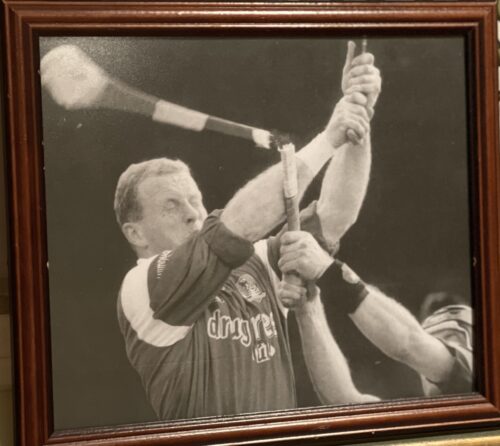

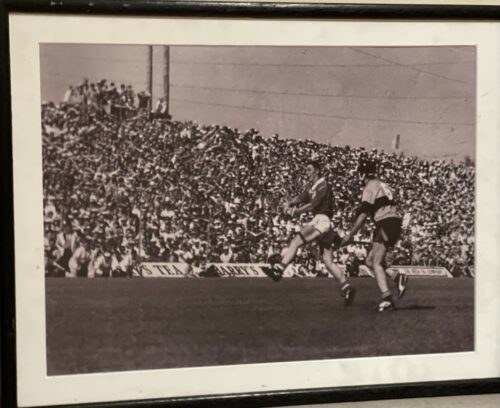

He was the third leader of Fianna Fáil from 1966 until 1979, succeeding the hugely influential Seán Lemass. Lynch was the last Fianna Fáil leader to secure (in 1977) an overall majority in the Dáil for his party. Historian and journalist T. Ryle Dwyer has called him "the most popular Irish politician since Daniel O'Connell." Before his political career Lynch had a successful sporting career as a dual player of Gaelic games. He played hurlingwith his local club Glen Rovers and with the Cork senior inter-county team from 1936 until 1950. Lynch also played Gaelic football with his local club St Nicholas' and with the Cork senior inter-county team from 1936 until 1946. In a senior inter-county hurling career that lasted for fourteen years he won five All-Ireland titles, seven Munster titles, three National Hurling League titles and seven Railway Cup titles. In a senior inter-county football career that lasted for ten years Lynch won one All-Ireland title, two Munster titles and one Railway Cup title. Lynch was later named at midfield on the Hurling Team of the Century and the Hurling Team of the MillenniumJohn Mary Lynch (15 August 1917 – 20 October 1999), known as Jack Lynch, was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Taoiseach from 1966 to 1973 and 1977 to 1979, Leader of Fianna Fáil from 1966 to 1979, Leader of the Opposition from 1973 to 1977, Minister for Finance from 1965 to 1966, Minister for Industry and Commerce from 1959 to 1965, Minister for Education 1957 to 1959, Minister for the Gaeltacht from March 1957 to June 1957, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Lands and Parliamentary Secretary to the Government from 1951 to 1954. He served as a Teachta Dála (TD) from 1948 to 1981. -

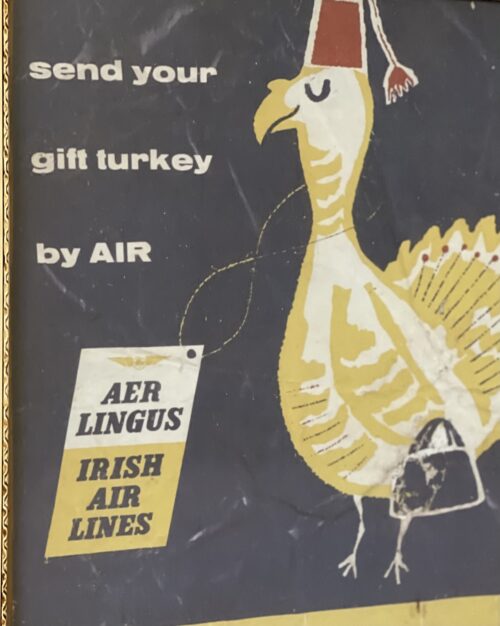

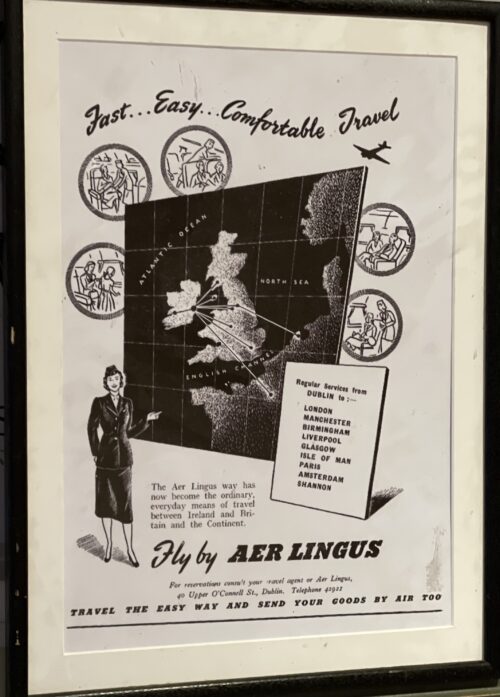

45cm x 34cm Aer Lingus was founded on 15 April 1936, with a capital of £100,000. Its first chairman was Seán Ó hUadhaigh.Pending legislation for Government investment through a parent company, Aer Lingus was associated with Blackpool and West Coast Air Services which advanced the money for the first aircraft, and operated with Aer Lingus under the common title "Irish Sea Airways". Aer Lingus Teoranta was registered as an airline on 22 May 1936.The name Aer Lingus was proposed by Richard F O'Connor, who was County Cork Surveyor, as well as an aviation enthusiast. On 27 May 1936, five days after being registered as an airline, its first service began between Baldonnel Airfield in Dublin and Bristol (Whitchurch) Airport, the United Kingdom, using a six-seater de Havilland DH.84 Dragon biplane (registration EI-ABI), named Iolar (Eagle). Later that year, the airline acquired its second aircraft, a four-engined biplane de Havilland DH.86 Express named "Éire", with a capacity of 14 passengers. This aircraft provided the first air link between Dublin and London by extending the Bristol service to Croydon. At the same time, the DH.84 Dragon was used to inaugurate an Aer Lingus service on the Dublin-Liverpool route. The airline was established as the national carrier under the Air Navigation and Transport Act (1936). In 1937, the Irish government created Aer Rianta (now called Dublin Airport Authority), a company to assume financial responsibility for the new airline and the entire country's civil aviation infrastructure. In April 1937, Aer Lingus became wholly owned by the Irish government via Aer Rianta. The airline's first General Manager was Dr J.F. (Jeremiah known as 'Jerry') Dempsey, a chartered accountant, who joined the company on secondment from Kennedy Crowley & Co (predecessor to KPMG as Company Secretary in 1936 (aged 30) and was appointed to the role of General Manager in 1937. He retired 30 years later in 1967 at the age of 60. In 1938, a de Havilland DH.89 Dragon Rapide replaced Iolar, and the company purchased a second DH.86B. Two Lockheed 14s arrived in 1939, Aer Lingus' first all-metal aircraft.In January 1940, a new airport opened in the Dublin suburb of Collinstown and Aer Lingus moved its operations there. It purchased a new DC-3 and inaugurated new services to Liverpool and an internal service to Shannon. The airline's services were curtailed during World War II with the sole route being to Liverpool or Barton Aerodrome Manchester depending on the fluctuating security situation.

45cm x 34cm Aer Lingus was founded on 15 April 1936, with a capital of £100,000. Its first chairman was Seán Ó hUadhaigh.Pending legislation for Government investment through a parent company, Aer Lingus was associated with Blackpool and West Coast Air Services which advanced the money for the first aircraft, and operated with Aer Lingus under the common title "Irish Sea Airways". Aer Lingus Teoranta was registered as an airline on 22 May 1936.The name Aer Lingus was proposed by Richard F O'Connor, who was County Cork Surveyor, as well as an aviation enthusiast. On 27 May 1936, five days after being registered as an airline, its first service began between Baldonnel Airfield in Dublin and Bristol (Whitchurch) Airport, the United Kingdom, using a six-seater de Havilland DH.84 Dragon biplane (registration EI-ABI), named Iolar (Eagle). Later that year, the airline acquired its second aircraft, a four-engined biplane de Havilland DH.86 Express named "Éire", with a capacity of 14 passengers. This aircraft provided the first air link between Dublin and London by extending the Bristol service to Croydon. At the same time, the DH.84 Dragon was used to inaugurate an Aer Lingus service on the Dublin-Liverpool route. The airline was established as the national carrier under the Air Navigation and Transport Act (1936). In 1937, the Irish government created Aer Rianta (now called Dublin Airport Authority), a company to assume financial responsibility for the new airline and the entire country's civil aviation infrastructure. In April 1937, Aer Lingus became wholly owned by the Irish government via Aer Rianta. The airline's first General Manager was Dr J.F. (Jeremiah known as 'Jerry') Dempsey, a chartered accountant, who joined the company on secondment from Kennedy Crowley & Co (predecessor to KPMG as Company Secretary in 1936 (aged 30) and was appointed to the role of General Manager in 1937. He retired 30 years later in 1967 at the age of 60. In 1938, a de Havilland DH.89 Dragon Rapide replaced Iolar, and the company purchased a second DH.86B. Two Lockheed 14s arrived in 1939, Aer Lingus' first all-metal aircraft.In January 1940, a new airport opened in the Dublin suburb of Collinstown and Aer Lingus moved its operations there. It purchased a new DC-3 and inaugurated new services to Liverpool and an internal service to Shannon. The airline's services were curtailed during World War II with the sole route being to Liverpool or Barton Aerodrome Manchester depending on the fluctuating security situation. An Aer Lingus Douglas DC-3 at Manchester Airport in 1948 wearing the first postwar livery.

An Aer Lingus Douglas DC-3 at Manchester Airport in 1948 wearing the first postwar livery.Post-war expansion

On 9 November 1945, regular services were resumed with an inaugural flight to London. From this point Aer Lingus aircraft, initially mostly Douglas DC-3s, were painted in a silver and green livery. The airline introduced its first flight attendants. In 1946, a new Anglo-Irish agreement gave Aer Lingus exclusive UK traffic rights from Ireland in exchange for a 40% holding by British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) and British European Airways (BEA). Because of Aer Lingus' growth the airline bought seven new Vickers Viking aircraft in 1947, however, these proved to be uneconomical and were soon sold.In 1947, Aerlínte Éireann came into existence to operate transatlantic flights to New York City from Ireland. The airline ordered five new Lockheed L-749 Constellations, but a change of government and a financial crisis prevented the service from starting. John A Costello, the incoming Fine Gael Taoiseach (Prime Minister), was not a keen supporter of air travel and thought that flying the Atlantic was too grandiose a scheme for a small airline from a small country like Ireland. A Bristol 170 Freighter at Manchester Airport in 1953.During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Aer Lingus introduced routes to Brussels, Amsterdam via Manchester and to Rome. Because of the expanding route structure, the airline became one of the early purchasers of Vickers Viscount 700s in 1951, which were placed in service in April 1954. In 1952, the airline expanded its all-freight services and acquired a small fleet of Bristol 170 Freighters, which remained in service until 1957. Prof. Patrick Lynch was appointed the chairman of Aer Lingus and Aer Rianta in 1954 and served in the position until 1975. In 1956, Aer Lingus introduced a new, green-top livery with a white lightning flash down the windows and the Irish flag displayed on the fin.

A Bristol 170 Freighter at Manchester Airport in 1953.During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Aer Lingus introduced routes to Brussels, Amsterdam via Manchester and to Rome. Because of the expanding route structure, the airline became one of the early purchasers of Vickers Viscount 700s in 1951, which were placed in service in April 1954. In 1952, the airline expanded its all-freight services and acquired a small fleet of Bristol 170 Freighters, which remained in service until 1957. Prof. Patrick Lynch was appointed the chairman of Aer Lingus and Aer Rianta in 1954 and served in the position until 1975. In 1956, Aer Lingus introduced a new, green-top livery with a white lightning flash down the windows and the Irish flag displayed on the fin. A Vickers Viscount 808 in "green top" livery at Manchester Airport in 1963.

A Vickers Viscount 808 in "green top" livery at Manchester Airport in 1963.First transatlantic service

On 28 April 1958, Aerlínte Éireann operated its first transatlantic service from Shannon to New York.In 1960, Aerlínte Éireann was renamed Aer Lingus. Aer Lingus bought seven Fokker F27 Friendships, which were delivered between November 1958 and May 1959. These were used in short-haul services to the UK, gradually replacing the Dakotas, until Aer Lingus replaced them in 1966 with secondhand Viscount 800s. The airline entered the jet age on 14 December 1960 when it received three Boeing 720 for use on the New York route and the newest Aer Lingus destination Boston. In 1963, Aer Lingus added Aviation Traders Carvairs to the fleet. These aircraft could transport five cars which were loaded into the fuselage through the nose of the aircraft. The Carvair proved to be uneconomical for the airline partly due to the rise of auto ferry services, and the aircraft were used for freight services until disposed of. The Boeing 720s proved to be a success for the airline on the transatlantic routes. To supplement these, Aer Lingus took delivery of its first larger Boeing 707 in 1964, and the type continued to serve the airline until 1986. A Boeing 720 in Aer Lingus-Irish International livery in 1965.

A Boeing 720 in Aer Lingus-Irish International livery in 1965.Jet aircraft

Conversion of the European fleet to jet equipment began in 1965 when the BAC One-Eleven started services on continental Europe.The airline adopted a new livery in the same year, with a large green shamrock on the fin. In 1966, the remainder of the company's shares held by Aer Rianta were transferred to the Minister for Finance. A Fokker F27 Friendship at Manchester Airport in 1965. The F27 was used on short-haul services between 1958 and 1966.In 1966, the company added routes to Montreal and Chicago. In 1968, flights from Belfast, in Northern Ireland, to New York City started, however, it was soon suspended due to the beginning of the Troubles.Aer Lingus introduced Boeing 737s to its fleet in 1969 to cope with the high demand for flights between Dublin and London. Later, Aer Lingus extended the 737 flights to all of its European networks. In 1967, after 30 years of service, General Manager Dr J.F. Dempsey signed the contract for the airline's first two Boeing 747 aircraft before he retired later that year.

A Fokker F27 Friendship at Manchester Airport in 1965. The F27 was used on short-haul services between 1958 and 1966.In 1966, the company added routes to Montreal and Chicago. In 1968, flights from Belfast, in Northern Ireland, to New York City started, however, it was soon suspended due to the beginning of the Troubles.Aer Lingus introduced Boeing 737s to its fleet in 1969 to cope with the high demand for flights between Dublin and London. Later, Aer Lingus extended the 737 flights to all of its European networks. In 1967, after 30 years of service, General Manager Dr J.F. Dempsey signed the contract for the airline's first two Boeing 747 aircraft before he retired later that year. An Aviation Traders Carvair that was used as a vehicle freighter is seen loading a car at Bristol Airport in 1964.

An Aviation Traders Carvair that was used as a vehicle freighter is seen loading a car at Bristol Airport in 1964. -

48cm x 35cm Aer Lingus was founded on 15 April 1936, with a capital of £100,000. Its first chairman was Seán Ó hUadhaigh.Pending legislation for Government investment through a parent company, Aer Lingus was associated with Blackpool and West Coast Air Services which advanced the money for the first aircraft, and operated with Aer Lingus under the common title "Irish Sea Airways". Aer Lingus Teoranta was registered as an airline on 22 May 1936.The name Aer Lingus was proposed by Richard F O'Connor, who was County Cork Surveyor, as well as an aviation enthusiast. On 27 May 1936, five days after being registered as an airline, its first service began between Baldonnel Airfield in Dublin and Bristol (Whitchurch) Airport, the United Kingdom, using a six-seater de Havilland DH.84 Dragon biplane (registration EI-ABI), named Iolar (Eagle). Later that year, the airline acquired its second aircraft, a four-engined biplane de Havilland DH.86 Express named "Éire", with a capacity of 14 passengers. This aircraft provided the first air link between Dublin and London by extending the Bristol service to Croydon. At the same time, the DH.84 Dragon was used to inaugurate an Aer Lingus service on the Dublin-Liverpool route. The airline was established as the national carrier under the Air Navigation and Transport Act (1936). In 1937, the Irish government created Aer Rianta (now called Dublin Airport Authority), a company to assume financial responsibility for the new airline and the entire country's civil aviation infrastructure. In April 1937, Aer Lingus became wholly owned by the Irish government via Aer Rianta. The airline's first General Manager was Dr J.F. (Jeremiah known as 'Jerry') Dempsey, a chartered accountant, who joined the company on secondment from Kennedy Crowley & Co (predecessor to KPMG as Company Secretary in 1936 (aged 30) and was appointed to the role of General Manager in 1937. He retired 30 years later in 1967 at the age of 60. In 1938, a de Havilland DH.89 Dragon Rapide replaced Iolar, and the company purchased a second DH.86B. Two Lockheed 14s arrived in 1939, Aer Lingus' first all-metal aircraft.In January 1940, a new airport opened in the Dublin suburb of Collinstown and Aer Lingus moved its operations there. It purchased a new DC-3 and inaugurated new services to Liverpool and an internal service to Shannon. The airline's services were curtailed during World War II with the sole route being to Liverpool or Barton Aerodrome Manchester depending on the fluctuating security situation.

48cm x 35cm Aer Lingus was founded on 15 April 1936, with a capital of £100,000. Its first chairman was Seán Ó hUadhaigh.Pending legislation for Government investment through a parent company, Aer Lingus was associated with Blackpool and West Coast Air Services which advanced the money for the first aircraft, and operated with Aer Lingus under the common title "Irish Sea Airways". Aer Lingus Teoranta was registered as an airline on 22 May 1936.The name Aer Lingus was proposed by Richard F O'Connor, who was County Cork Surveyor, as well as an aviation enthusiast. On 27 May 1936, five days after being registered as an airline, its first service began between Baldonnel Airfield in Dublin and Bristol (Whitchurch) Airport, the United Kingdom, using a six-seater de Havilland DH.84 Dragon biplane (registration EI-ABI), named Iolar (Eagle). Later that year, the airline acquired its second aircraft, a four-engined biplane de Havilland DH.86 Express named "Éire", with a capacity of 14 passengers. This aircraft provided the first air link between Dublin and London by extending the Bristol service to Croydon. At the same time, the DH.84 Dragon was used to inaugurate an Aer Lingus service on the Dublin-Liverpool route. The airline was established as the national carrier under the Air Navigation and Transport Act (1936). In 1937, the Irish government created Aer Rianta (now called Dublin Airport Authority), a company to assume financial responsibility for the new airline and the entire country's civil aviation infrastructure. In April 1937, Aer Lingus became wholly owned by the Irish government via Aer Rianta. The airline's first General Manager was Dr J.F. (Jeremiah known as 'Jerry') Dempsey, a chartered accountant, who joined the company on secondment from Kennedy Crowley & Co (predecessor to KPMG as Company Secretary in 1936 (aged 30) and was appointed to the role of General Manager in 1937. He retired 30 years later in 1967 at the age of 60. In 1938, a de Havilland DH.89 Dragon Rapide replaced Iolar, and the company purchased a second DH.86B. Two Lockheed 14s arrived in 1939, Aer Lingus' first all-metal aircraft.In January 1940, a new airport opened in the Dublin suburb of Collinstown and Aer Lingus moved its operations there. It purchased a new DC-3 and inaugurated new services to Liverpool and an internal service to Shannon. The airline's services were curtailed during World War II with the sole route being to Liverpool or Barton Aerodrome Manchester depending on the fluctuating security situation. An Aer Lingus Douglas DC-3 at Manchester Airport in 1948 wearing the first postwar livery.

An Aer Lingus Douglas DC-3 at Manchester Airport in 1948 wearing the first postwar livery.Post-war expansion

On 9 November 1945, regular services were resumed with an inaugural flight to London. From this point Aer Lingus aircraft, initially mostly Douglas DC-3s, were painted in a silver and green livery. The airline introduced its first flight attendants. In 1946, a new Anglo-Irish agreement gave Aer Lingus exclusive UK traffic rights from Ireland in exchange for a 40% holding by British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) and British European Airways (BEA). Because of Aer Lingus' growth the airline bought seven new Vickers Viking aircraft in 1947, however, these proved to be uneconomical and were soon sold.In 1947, Aerlínte Éireann came into existence to operate transatlantic flights to New York City from Ireland. The airline ordered five new Lockheed L-749 Constellations, but a change of government and a financial crisis prevented the service from starting. John A Costello, the incoming Fine Gael Taoiseach (Prime Minister), was not a keen supporter of air travel and thought that flying the Atlantic was too grandiose a scheme for a small airline from a small country like Ireland. A Bristol 170 Freighter at Manchester Airport in 1953.During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Aer Lingus introduced routes to Brussels, Amsterdam via Manchester and to Rome. Because of the expanding route structure, the airline became one of the early purchasers of Vickers Viscount 700s in 1951, which were placed in service in April 1954. In 1952, the airline expanded its all-freight services and acquired a small fleet of Bristol 170 Freighters, which remained in service until 1957. Prof. Patrick Lynch was appointed the chairman of Aer Lingus and Aer Rianta in 1954 and served in the position until 1975. In 1956, Aer Lingus introduced a new, green-top livery with a white lightning flash down the windows and the Irish flag displayed on the fin.

A Bristol 170 Freighter at Manchester Airport in 1953.During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Aer Lingus introduced routes to Brussels, Amsterdam via Manchester and to Rome. Because of the expanding route structure, the airline became one of the early purchasers of Vickers Viscount 700s in 1951, which were placed in service in April 1954. In 1952, the airline expanded its all-freight services and acquired a small fleet of Bristol 170 Freighters, which remained in service until 1957. Prof. Patrick Lynch was appointed the chairman of Aer Lingus and Aer Rianta in 1954 and served in the position until 1975. In 1956, Aer Lingus introduced a new, green-top livery with a white lightning flash down the windows and the Irish flag displayed on the fin. A Vickers Viscount 808 in "green top" livery at Manchester Airport in 1963.

A Vickers Viscount 808 in "green top" livery at Manchester Airport in 1963.First transatlantic service

On 28 April 1958, Aerlínte Éireann operated its first transatlantic service from Shannon to New York.In 1960, Aerlínte Éireann was renamed Aer Lingus. Aer Lingus bought seven Fokker F27 Friendships, which were delivered between November 1958 and May 1959. These were used in short-haul services to the UK, gradually replacing the Dakotas, until Aer Lingus replaced them in 1966 with secondhand Viscount 800s. The airline entered the jet age on 14 December 1960 when it received three Boeing 720 for use on the New York route and the newest Aer Lingus destination Boston. In 1963, Aer Lingus added Aviation Traders Carvairs to the fleet. These aircraft could transport five cars which were loaded into the fuselage through the nose of the aircraft. The Carvair proved to be uneconomical for the airline partly due to the rise of auto ferry services, and the aircraft were used for freight services until disposed of. The Boeing 720s proved to be a success for the airline on the transatlantic routes. To supplement these, Aer Lingus took delivery of its first larger Boeing 707 in 1964, and the type continued to serve the airline until 1986. A Boeing 720 in Aer Lingus-Irish International livery in 1965.

A Boeing 720 in Aer Lingus-Irish International livery in 1965.Jet aircraft

Conversion of the European fleet to jet equipment began in 1965 when the BAC One-Eleven started services on continental Europe.The airline adopted a new livery in the same year, with a large green shamrock on the fin. In 1966, the remainder of the company's shares held by Aer Rianta were transferred to the Minister for Finance. A Fokker F27 Friendship at Manchester Airport in 1965. The F27 was used on short-haul services between 1958 and 1966.In 1966, the company added routes to Montreal and Chicago. In 1968, flights from Belfast, in Northern Ireland, to New York City started, however, it was soon suspended due to the beginning of the Troubles.Aer Lingus introduced Boeing 737s to its fleet in 1969 to cope with the high demand for flights between Dublin and London. Later, Aer Lingus extended the 737 flights to all of its European networks. In 1967, after 30 years of service, General Manager Dr J.F. Dempsey signed the contract for the airline's first two Boeing 747 aircraft before he retired later that year.

A Fokker F27 Friendship at Manchester Airport in 1965. The F27 was used on short-haul services between 1958 and 1966.In 1966, the company added routes to Montreal and Chicago. In 1968, flights from Belfast, in Northern Ireland, to New York City started, however, it was soon suspended due to the beginning of the Troubles.Aer Lingus introduced Boeing 737s to its fleet in 1969 to cope with the high demand for flights between Dublin and London. Later, Aer Lingus extended the 737 flights to all of its European networks. In 1967, after 30 years of service, General Manager Dr J.F. Dempsey signed the contract for the airline's first two Boeing 747 aircraft before he retired later that year. An Aviation Traders Carvair that was used as a vehicle freighter is seen loading a car at Bristol Airport in 1964.

An Aviation Traders Carvair that was used as a vehicle freighter is seen loading a car at Bristol Airport in 1964. -

48cm x 35cm

48cm x 35cmIt was Richie Connor in the early 1990s who first introduced me to the concept. For the Offaly team he captained, ultimately to the 1982 All-Ireland, beating Dublin in the 1980 Leinster final had he said been their most significant achievement.

This was because winning the province represented a longer journey from where the team under Eugene McGee had started than the distance from there to the Sam Maguire.

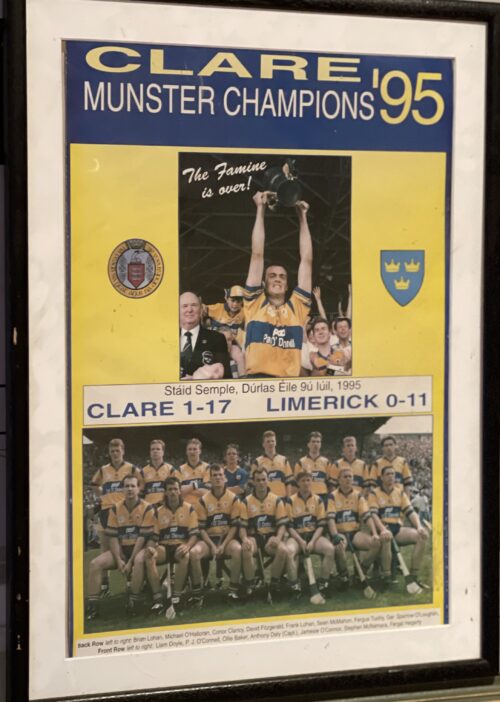

Maybe the reasoning was slightly different in Clare but it amounted to the same thing. In the few weeks that shimmered in the radiant summer of 1995 between winning Munster and the All-Ireland semi-final against Galway, manager Ger Loughnane was certainly of that view.

“In Clare, Munster is the Mount Everest. All along Munster was what was talked about. I remember stopping Nenagh on the way back from the League final and a man saying, ‘if only we could win Munster once, it would make up for everything’.

“The reaction to our winning Munster has been far greater than what would happen in other counties if they won an All-Ireland.”

Clare had got to the stage where they were being upstaged by their footballers whose first Munster title since 1917 had been sensationally won in 1992 leaving the hurlers by-passed.

Anthony Daly, prominent in 1995 as the exuberant captain of the hurlers, remembered the big-ball community’s notions. He went to support the footballers in their All-Ireland semi-final against Dublin three years previously. In a bar beforehand he was mocked for band-wagoning.

“Do you go to our matches at all,” asks Daly.

“I do, I do,” comes the response.

“And when you do, does anyone ever tell you to f*** off back to west Clare?”

Boom, boom.

Climbed Everest

Twenty-five years ago today (Thursday) the county hurlers climbed Everest and in unexpected style. Clare had qualified for a third successive Munster final but the previous two, against Limerick and Tipperary had ended in heavy defeats.