antr

antr

|

|

|

|

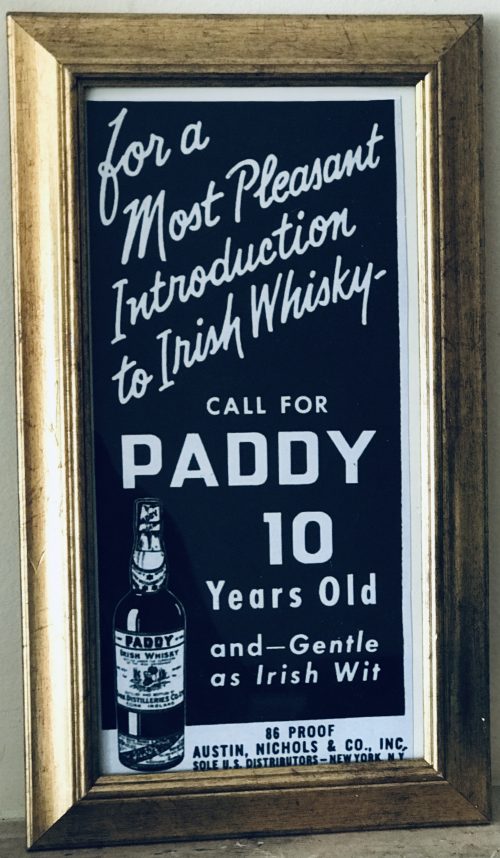

| Introduced | 1879, renamed as Paddy in 1912 |

|---|---|

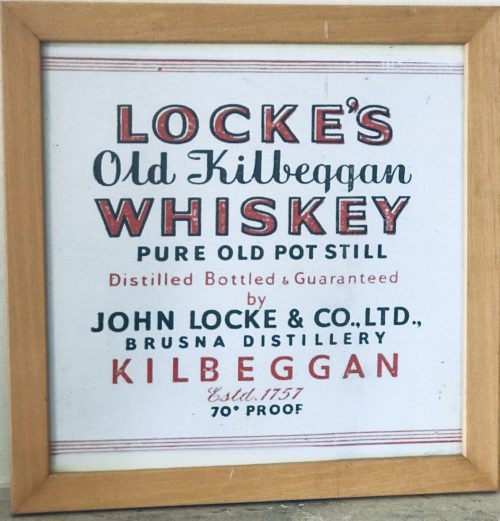

An Address from the People of Kilbeggan to John Locke, Esq. Dear Sir - Permit us, your fellow townsmen, to assure of our deep and cordial sympathy in your loss and disappointment from the accident which occurred recently in your Distillery. Sincerely as we regret the accident, happily unattended with loss of life, we cannot but rejoice at the long-wished-for opportunity it affords us of testifying to you the high appreciation in which we hold you for your public and private worth. We are well aware that the restrictions imposed by recent legislation on that particular branch of Irish industry, with which you have been so long identified, have been attended with disastrous results to the trade, as is manifest in the long list of Distilleries now almost in ruins, and which were a few years ago centres of busy industry, affording remunerative employment to thousands of hands; and we are convinced the Kilbeggan Distillery would have long since swelled the dismal catalogue had it fallen into less energetic and enterprising hands. In such an event we would be compelled to witness the disheartening scene of a large number of our working population without employment during that period of the year when employment Is scarcest, and at the same time most essential to the poor. Independent then of what we owe you, on purely personal grounds, we feel we owe you a deep debt of gratitude for maintaining in our midst a manufacture which affords such extensive employment to our poor, and exercises so favourable an influence on the prosperity of the town. In conclusion, dear Sir, we beg your acceptance of a new steam boiler to replace the injured one, as testimony, inadequate though it is, of our unfeigned respect and esteems for you ; and we beg to present it with the ardent wish and earnest hope that, for many long years to come, it may contribute to enhance still more the deservedly high and increasing reputation of the Kilbeggan Distillery.In a public response to mark the gift, also published in several newspapers, Locke thanked the people of Kilbeggan for their generosity, stating "...I feel this to be the proudest day of my life...". A plaque commemorating the event hangs in the distillery's restaurant today. In 1878, a fire broke out in the "can dip" (sampling) room of the distillery, and spread rapidly. Although, the fire was extinguished within an hour, it destroying a considerable portion of the front of the distillery and caused £400 worth of damage. Hundreds of gallons of new whiskey were also consumed in the blaze - however, the distillery is said to have been saved from further physical and financial ruin through the quick reaction of townsfolk who broke down the doors of the warehouses, and helped roll thousands of casks of ageing spirit down the street to safety. In 1887, the distillery was visited by Alfred Barnard, a British writer, as research for his book, "the Whiskey Distilleries of the United Kingdom". By then, the much enlarged distillery was being managed by John's sons, John Edward and James Harvey, who told Barnard that the distillery's output had more than doubled during the preceding ten years, and that they intended to install electric lighting.Barnard noted that the distillery, which he referred to as the "Brusna Distillery", named for the nearby river, was said to be the oldest in Ireland. According to Barnard, the distillery covered 5 acres, and employed a staff of about 70 men, with the aged and sick pensioned-off or assisted. At the time of his visit, the distillery was producing 157,200 proof gallons per annum, though it had the capacity to produce 200,000. The whiskey, which was sold primarily in Dublin, England, and "the Colonies", was "old pot still", produced using four pot stills (two wash stills: 10,320 / 8,436 gallons; and two spirit stills: 6,170 / 6,080 gallons), which had been installed by Millar and Company, Dublin. Barnard remarked that at the time of his visit over 2,000 casks of spirit were ageing in the distillery's bonded warehouses. In 1893, the distillery ceased to be privately held, and was converted a limited stock company, trading as John Locke & Co., Ltd., with nominal capital of £40,000.

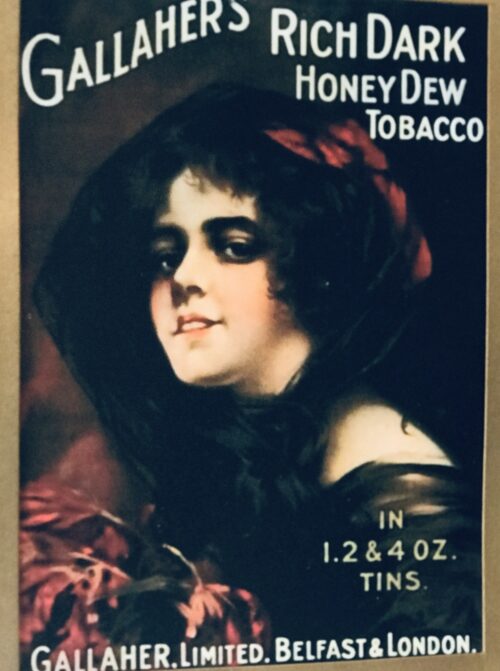

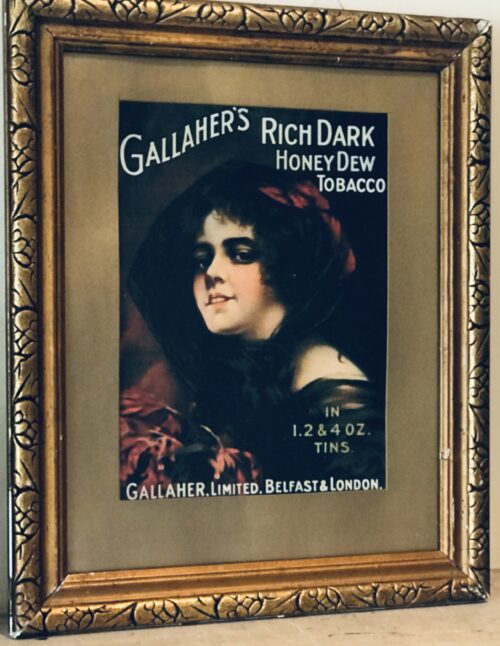

Gallaher continued to work at his desk every day until a few months before he died in 1927. He was remembered as a courteous, kindly man, a generous employer, and an extremely talented businessman. His plain ways endeared him to people. He left an estate valued at £503,954.The company was principally inherited by his nephew, John Gallaher Michaels (1880 – 1948). Michaels had worked for his uncle for many years, and had been manger of the American operations.The Constructive Finance & Investment Co, led by Edward de Stein (1887 – 1965), acquired the entire share capital of Gallaher for several million pounds in 1929, and offered shares to the public.Why Michaels divested his stake in Gallaher remains unclear, but he, his uncle and his brother all lacked heirs, so perhaps he simply wished to retire and pass on management of the company to others.A new factory was established at East Wall, Dublin for £250,000 in 1929. The East Wall factory was closed with the loss of 400 jobs, following the introduction of a tariff on businesses not majority-owned by Irish residents, in 1932.Imperial Tobacco acquired 51 percent of Gallaher for £1.25 million in 1932. Gallaher retained its managerial independence, and the Imperial Tobacco move was executed with the intention of blocking a potential bid for Gallaher from the American Tobacco Company.Gallaher was the fourth largest cigarette manufacturer in Britain by 1932.Gallaher acquired Peter Jackson in 1934. The firm manufactured Du Maurier cigarettes, which was the first popular filter-tip brand in Britain.E Robinson & Son, manufacturers of Senior Service cigarettes, was acquired in 1937. Senior Service had been highly successful within the Manchester area, but Robinson’s had lacked the capital to take the brand nationwide.

J Freeman & Son, cigar manufacturers of Cardiff, was acquired in 1947.Gallaher acquired Cope Brothers of Liverpool, owners of the Old Holborn brand, in 1952.Benson & Hedges was acquired, mainly for the prestigious brand name, in 1955.Gallaher sales grew rapidly in the 1950s. Senior Service and Park Drive became respectively the third and fourth highest selling cigarettes in Britain in 1959, by which time Gallaher held 30 percent of the British tobacco market.Gallaher acquired J Wix & Sons Ltd, the fast-growing manufacturer of Kensitas cigarettes, from the American Tobacco Company in 1961.The Imperial Tobacco stake in Gallaher had been diluted to 37 percent by 1961.

Gallaher claimed 37 percent of the British cigarette market by 1962.A large factory was established at Airton Road, Dublin in 1963.Silk Cut was launched as a low-tar brand in 1964.

Gallaher employed 15,000 people in 1965, and had an authorised capital of £45 million in 1968. The company held 27 percent of the British tobacco market in 1968.Benson & Hedges was the leading king-size cigarette brand in Britain by 1981.The Belfast factory was closed in 1988. 700 jobs were lost, and production was relocated to Ballymena in County Antrim.

A cigar factory in Port Talbot, Wales was closed with the loss of 370 jobs in 1994.The Manchester cigarette factory was closed in 2000-1. Nearly 1,000 jobs were lost. Production was transferred to Ballymena, where 300 extra jobs were created.Japan Tobacco acquired Gallaher, by then the fifth largest tobacco company in the world, for £7.5 billion in cash in 2007.Ballymena, the last remaining tobacco factory in the UK, was closed in 2017, with production relocated to Eastern Europe. 860 jobs were lost.

Gallaher continued to work at his desk every day until a few months before he died in 1927. He was remembered as a courteous, kindly man, a generous employer, and an extremely talented businessman. His plain ways endeared him to people. He left an estate valued at £503,954.The company was principally inherited by his nephew, John Gallaher Michaels (1880 – 1948). Michaels had worked for his uncle for many years, and had been manger of the American operations.The Constructive Finance & Investment Co, led by Edward de Stein (1887 – 1965), acquired the entire share capital of Gallaher for several million pounds in 1929, and offered shares to the public.Why Michaels divested his stake in Gallaher remains unclear, but he, his uncle and his brother all lacked heirs, so perhaps he simply wished to retire and pass on management of the company to others.A new factory was established at East Wall, Dublin for £250,000 in 1929. The East Wall factory was closed with the loss of 400 jobs, following the introduction of a tariff on businesses not majority-owned by Irish residents, in 1932.Imperial Tobacco acquired 51 percent of Gallaher for £1.25 million in 1932. Gallaher retained its managerial independence, and the Imperial Tobacco move was executed with the intention of blocking a potential bid for Gallaher from the American Tobacco Company.Gallaher was the fourth largest cigarette manufacturer in Britain by 1932.Gallaher acquired Peter Jackson in 1934. The firm manufactured Du Maurier cigarettes, which was the first popular filter-tip brand in Britain.E Robinson & Son, manufacturers of Senior Service cigarettes, was acquired in 1937. Senior Service had been highly successful within the Manchester area, but Robinson’s had lacked the capital to take the brand nationwide.

J Freeman & Son, cigar manufacturers of Cardiff, was acquired in 1947.Gallaher acquired Cope Brothers of Liverpool, owners of the Old Holborn brand, in 1952.Benson & Hedges was acquired, mainly for the prestigious brand name, in 1955.Gallaher sales grew rapidly in the 1950s. Senior Service and Park Drive became respectively the third and fourth highest selling cigarettes in Britain in 1959, by which time Gallaher held 30 percent of the British tobacco market.Gallaher acquired J Wix & Sons Ltd, the fast-growing manufacturer of Kensitas cigarettes, from the American Tobacco Company in 1961.The Imperial Tobacco stake in Gallaher had been diluted to 37 percent by 1961.

Gallaher claimed 37 percent of the British cigarette market by 1962.A large factory was established at Airton Road, Dublin in 1963.Silk Cut was launched as a low-tar brand in 1964.

Gallaher employed 15,000 people in 1965, and had an authorised capital of £45 million in 1968. The company held 27 percent of the British tobacco market in 1968.Benson & Hedges was the leading king-size cigarette brand in Britain by 1981.The Belfast factory was closed in 1988. 700 jobs were lost, and production was relocated to Ballymena in County Antrim.

A cigar factory in Port Talbot, Wales was closed with the loss of 370 jobs in 1994.The Manchester cigarette factory was closed in 2000-1. Nearly 1,000 jobs were lost. Production was transferred to Ballymena, where 300 extra jobs were created.Japan Tobacco acquired Gallaher, by then the fifth largest tobacco company in the world, for £7.5 billion in cash in 2007.Ballymena, the last remaining tobacco factory in the UK, was closed in 2017, with production relocated to Eastern Europe. 860 jobs were lost.

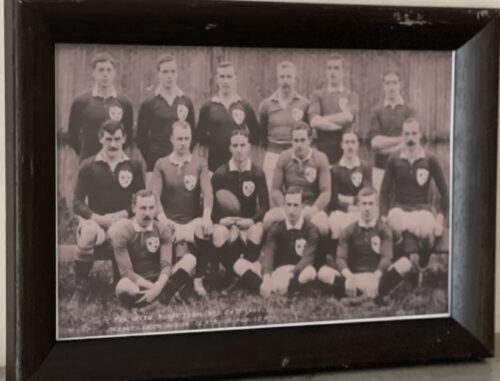

| Position | Nation | Games | Points | Table points | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Played | Won | Drawn | Lost | For | Against | Difference | |||

| 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 9 | +52 | 8 | |

| 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 33 | 32 | +1 | 4 | |

| 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 29 | 36 | −7 | 4 | |

| 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 22 | 38 | −16 | 2 | |

| 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 19 | 49 | −30 | 2 | |

|

24 November |

| Ireland |

12–15 | |

|---|---|---|

| Try: Sugars (2), Maclear Pen: Parke | Report | Try: Loubser (2), Krige, Stegmann Pen: Joubert |

|

Balmoral Showgrounds, Belfast

Attendance: 15,000

Referee: JD Tulloch (Scotland) |

Since the days of O'Connell a larger public demonstration has not been witnessed than that of Sunday last. About 1 o'clock the monster procession started from Claremorris, headed by several thousand men on foot – the men of each district wearing a laural leaf or green ribbon in hat or coat to distinguish the several contingents. At 11 o'clock a monster contingent of tenant-farmers on horseback drew up in front of Hughes's hotel, showing discipline and order that a cavalry regiment might feel proud of. They were led on in sections, each having a marshal who kept his troops well in hand. Messrs. P.W. Nally, J.W. Nally, H. French, and M. Griffin, wearing green and gold sashes, led on their different sections, who rode two deep, occupying, at least, over an Irish mile of the road. Next followed a train of carriages, brakes, cares, etc. led on by Mr. Martin Hughes, the spirited hotel proprietor, driving a pair of rare black ponies to a phæton, taking Messrs. J.J. Louden and J. Daly. Next came Messrs. O'Connor, J. Ferguson, and Thomas Brennan in a covered carriage, followed by at least 500 vehicles from the neighbouring towns. On passing through Ballindine the sight was truly imposing, the endless train directing its course to Irishtown – a neat little hamlet on the boundaries of Mayo, Roscommon, and Galway.Evolving out of this a number of local land league organisations were set up to work against the excessive rents being demanded by landlords throughout Ireland, but especially in Mayo and surrounding counties. From 1874 agricultural prices in Europe had dropped, followed by some bad harvests due to wet weather during the Long Depression. The effect by 1878 was that many Irish farmers were unable to pay the rents that they had agreed, particularly in the poorer and wetter parts of Connacht. The localised 1879 Famine added to the misery. Unlike many other parts of Europe, the Irish land tenure system was inflexible in times of economic hardship.

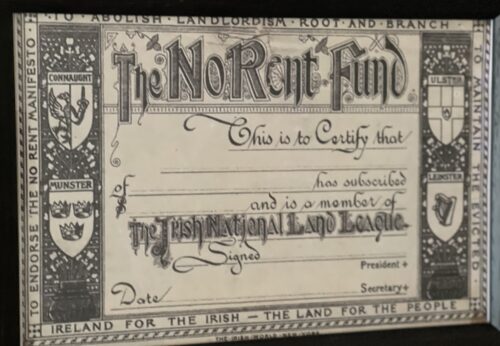

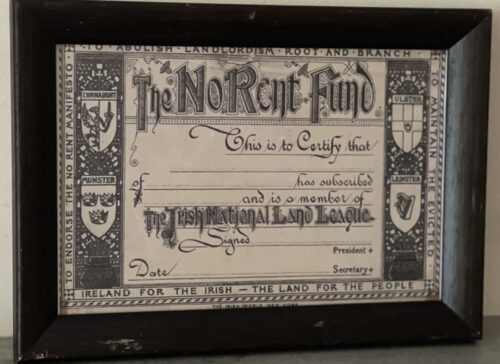

..."first, to bring about a reduction of rack-rents; second, to facilitate the obtaining of the ownership of the soil by the occupiers". That the object of the League can be best attained by promoting organisation among the tenant-farmers; by defending those who may be threatened with eviction for refusing to pay unjust rents; by facilitating the working of the Bright clauses of the Irish Land Act during the winter; and by obtaining such reforms in the laws relating to land as will enable every tenant to become owner of his holding by paying a fair rent for a limited number of years".Charles Stewart Parnell, John Dillon, Michael Davitt, and others then went to the United States to raise funds for the League with spectacular results. Branches were also set up in Scotland, where the Crofters Party imitated the League and secured a reforming Act in 1886. The government had introduced the first Land Act in 1870, which proved largely ineffective. It was followed by the marginally more effective Land Acts of 1880 and 1881. These established a Land Commission that started to reduce some rents. Parnell together with all of his party lieutenants, including Father Eugene Sheehyknown as "the Land League priest", went into a bitter verbal offensive and were imprisoned in October 1881 under the Irish Coercion Act in Kilmainham Jail for "sabotaging the Land Act", from where the No-Rent Manifesto was issued, calling for a national tenant farmer rent strike until "constitutional liberties" were restored and the prisoners freed. It had a modest success In Ireland, and mobilized financial and political support from the Irish Diaspora. Although the League discouraged violence, agrarian crimes increased widely. Typically a rent strike would be followed by eviction by the police and the bailiffs. Tenants who continued to pay the rent would be subject to a boycott, or as it was contemporaneously described in the US press, an "excommunication" by local League members.Where cases went to court, witnesses would change their stories, resulting in an unworkable legal system. This in turn led on to stronger criminal laws being passed that were described by the League as "Coercion Acts". The bitterness that developed helped Parnell later in his Home Rule campaign. Davitt's views as seen in his famous slogan: "The land of Ireland for the people of Ireland" was aimed at strengthening the hold on the land by the peasant Irish at the expense of the alien landowners.Parnell aimed to harness the emotive element, but he and his party were strictly constitutional. He envisioned tenant farmers as potential freeholders of the land they had rented. In the Encyclopedia Britannica, the League is considered part of the progressive "rise of fenianism".

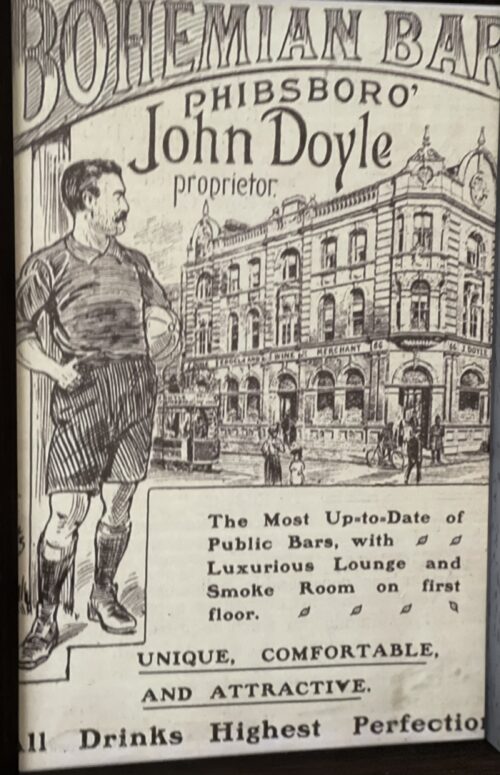

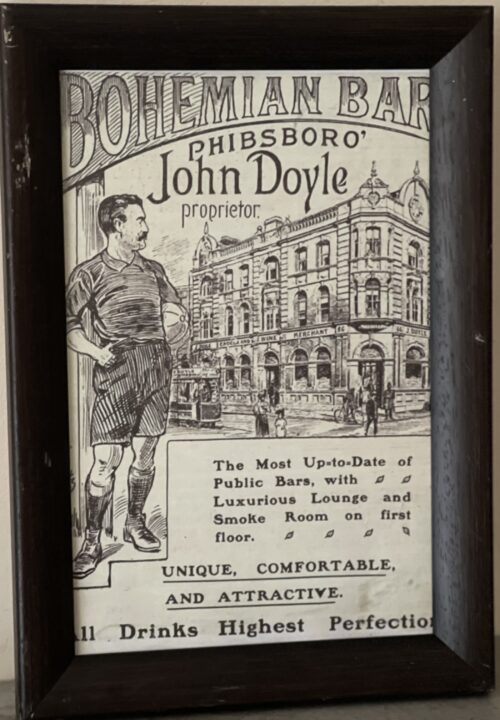

Next to a statue or the freedom of the city, perhaps the most select honour you can earn in Dublin is to have a street corner named after you in perpetuity. It’s a very rare distinction, available mainly – it seems – to publicans, whose premises command an important junction for a substantial period. It’s also entirely in the public’s gift, not officialdom’s. And the vast majority of city corners are never so named. I can think of fewer than 10 that have been, including Doyle’s, Hanlon’s, Hart’s, Kelly’s, and Leonard’s. Some of those names have long outlived the original businesses, although that said, “perpetuity” may be overstating their lease, as the case of Doyle’s illustrates.

Anyone who was at the annual Bloomsday re-enactment in Glasnevin last Sunday will have been reminded that Doyle’s Corner, in nearby Phibsboro, used to be “Dunphy’s”. As such, it was mentioned in Ulysses for its prominent role in city funerals, including the fictional Paddy Dignam’s, as the last right-angle turn towards the cemetery.

Hence, as Leopold Bloom’s interior voice records: “Dunphy’s corner. Mourning coaches drawn up drowning their grief. A pause by the wayside. Tiptop position for a pub. Expect we’ll pull up here on the way back to drink his health. Pass around the consolation. Elixir of life.”

It also inspires a joke by one of the other passengers in the carriage: “First round Dunphy’s, Mr Dedalus said, nodding. Gordon Bennett Cup.”

His reference to the famous motor race may have been a nod to the haste with which some corteges used to move in those years, under pressure from the cemetery’s restrictive opening hours. In a series of newspaper essays, The Streets of Dublin 1910-11, the then Alderman Thomas Kelly complained he had never seen in any other Irish city “the galloping which, more especially on Sunday’s, disgraces Dublin funerals”.

That same alderman – a future Sinn Féin TD – was the Kelly for whom Kelly’s Corner is named, an honour all the more unusual because he owned a shop rather than a pub. But for apparent immortality in those years, his corner would have had to bow to Dunphy’s, which enjoyed a whole different level of fame. As he also writes, “Rounding Dunphy’s Corner” had become a popular Dublin euphemism for life’s last journey.

Even in 1904, however, Dunphy’s pub had already made way for one called Doyle’s, and the corner name gradually followed. There must have been a period when it was known as both, because the news archives for 1906 have a story about a collapse of scaffolding at “Doyle’s Corner”, during rebuilding of the premises there. Among five people injured, incidentally, was “a man named Coleman, from Exchange Street”, who had also survived the sewer gas tragedy in a manhole on Burgh Quay the year previous (to which there remains today a monument). Talk about luck.

No doubt even the indestructible Coleman rounded Dunphy’s Corner eventually. In any case, by the 1920s, the Phibsboro Junction was firmly established as Doyle’s Corner, and is still known as that, its latter-day notoriety secured by regular mentions on AA Roadwatch. Nobody calls it Dunphy’s Corner anymore.

Mind you, the same location proves that mere changes of ownership do not in themselves confer naming privileges. For a time in the middle of the last century, I gather, there was also a Murphy’s pub on the site, the owner of which erected a sign proclaiming “Murphy’s Corner”. The public did not take the hint.

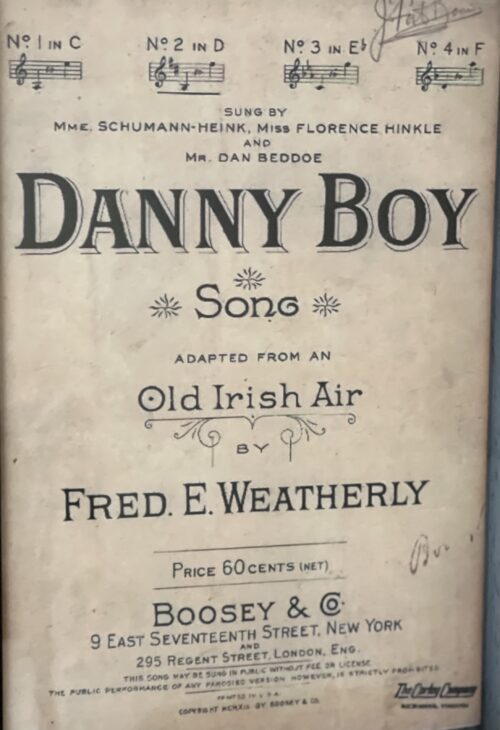

| "Danny Boy" | |

|---|---|

Danny Boy |

|

| Song | |

| Published | 1913 |

| Genre | Folk |

| Songwriter(s) | Frederic Weatherly (lyrics) in 1910 |

| Recording | |

|

MENU

0:00

Performed by Celtic Aire of the United States Air Force Band

|

|

Oh, Danny boy, the pipes, the pipes are calling From glen to glen, and down the mountain side. The summer's gone, and all the roses falling, It's you, It's you must go and I must bide. But come ye back when summer's in the meadow, Or when the valley's hushed and white with snow, It's I'll be there in sunshine or in shadow,— Oh, Danny boy, Oh Danny boy, I love you so! But when ye come, and all the flowers are dying, If I am dead, as dead I well may be, Ye'll come and find the place where I am lying, And kneel and say an Avé there for me. And I shall hear, though soft you tread above me, And all my grave will warmer, sweeter be, For you will bend and tell me that you love me, And I shall sleep in peace until you come to me!

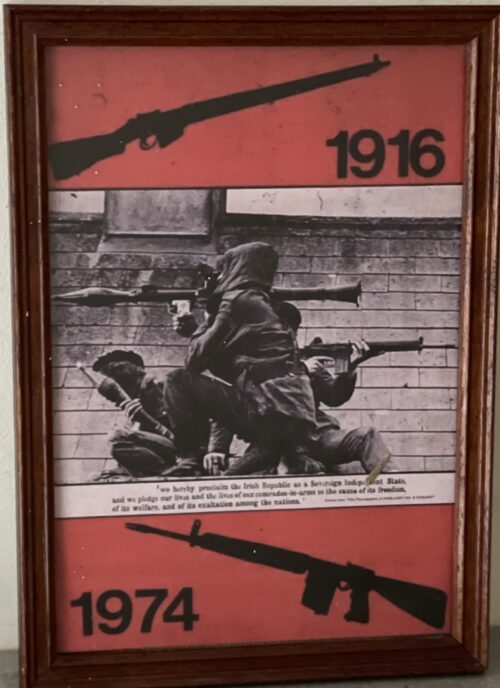

The Troubles, also called Northern Ireland conflict, violent sectarian conflict from about 1968 to 1998 in Northern Irelandbetween the overwhelmingly Protestantunionists (loyalists), who desired the province to remain part of the United Kingdom, and the overwhelmingly Roman Catholic nationalists (republicans), who wanted Northern Ireland to become part of the republic of Ireland. The other major players in the conflict were the British army, Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR; from 1992 called the Royal Irish Regiment), and their avowed purpose was to play a peacekeeping role, most prominently between the nationalist Irish Republican Army(IRA), which viewed the conflict as a guerrilla war for national independence, and the unionist paramilitary forces, which characterized the IRA’s aggression as terrorism. Marked by street fighting, sensational bombings, sniper attacks, roadblocks, and internment without trial, the confrontation had the characteristics of a civil war, notwithstanding its textbook categorization as a “low-intensity conflict.” Some 3,600 people were killed and more than 30,000 more were wounded before a peaceful solution, which involved the governments of both the United Kingdom and Ireland, was effectively reached in 1998, leading to a power-sharing arrangement in the Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont.

The story of the Troubles is inextricably entwined with the history of Ireland as whole and, as such, can be seen as stemming from the first British incursion on the island, the Anglo-Norman invasion of the late 12th century, which left a wave of settlers whose descendants became known as the “Old English.” Thereafter, for nearly eight centuries, England and then Great Britain as a whole would dominate affairs in Ireland. Colonizing British landlords widely displaced Irish landholders. The most successful of these “plantations” began taking hold in the early 17th century in Ulster, the northernmost of Ireland’s four traditional provinces, previously a centre of rebellion, where the planters included English and Scottish tenants as well as British landlords. Because of the plantation of Ulster, as Irish history unfolded—with the struggle for the emancipation of the island’s Catholic majority under the supremacy of the Protestant ascendancy, along with the Irish nationalist pursuit of Home Rule and then independence after the island’s formal union with Great Britain in 1801—Ulster developed as a region where the Protestant settlers outnumbered the indigenousIrish. Unlike earlier English settlers, most of the 17th-century English and Scottish settlers and their descendants did not assimilate with the Irish. Instead, they held on tightly to British identity and remained steadfastly loyal to the British crown.

Of the nine modern counties that constituted Ulster in the early 20th century, four—Antrim, Down, Armagh, and Londonderry (Derry)—had significant Protestant loyalist majorities; two—Fermanagh and Tyrone—had small Catholic nationalist majorities; and three—Donegal, Cavan, and Monaghan—had significant Catholic nationalist majorities. In 1920, during the Irish War of Independence (1919–21), the British Parliament, responding largely to the wishes of Ulster loyalists, enacted the Government of Ireland Act , which divided the island into two self-governing areas with devolved Home Rule-like powers. What would come to be known as Northern Ireland was formed by Ulster’s four majority loyalist counties along with Fermanagh and Tyrone. Donegal, Cavan, and Monaghan were combined with the island’s remaining 23 counties to form southern Ireland. The Anglo-Irish Treaty that ended the War of Independence then created the Irish Free State in the south, giving it dominion status within the British Empire. It also allowed Northern Ireland the option of remaining outside of the Free State, which it unsurprisingly chose to do.

Thus, in 1922 Northern Ireland began functioning as a self-governing region of the United Kingdom. Two-thirds of its population (about one million people) was Protestant and about one-third (roughly 500,000 people) was Catholic. Well before partition, Northern Ireland, particularly Belfast, had attracted economic migrants from elsewhere in Ireland seeking employment in its flourishing linen-making and shipbuilding industries. The best jobs had gone to Protestants, but the humming local economy still provided work for Catholics. Over and above the long-standing dominance of Northern Ireland politics that resulted for the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) by virtue of the Protestants’ sheer numerical advantage, loyalist control of local politics was ensured by the gerrymandering of electoral districts that concentrated and minimized Catholic representation. Moreover, by restricting the franchise to ratepayers (the taxpaying heads of households) and their spouses, representation was further limited for Catholic households, which tended to be larger (and more likely to include unemployed adult children) than their Protestant counterparts. Those who paid rates for more than one residence (more likely to be Protestants) were granted an additional vote for each ward in which they held property (up to six votes). Catholics argued that they were discriminated against when it came to the allocation of public housing, appointments to public service jobs, and government investment in neighbourhoods. They were also more likely to be the subjects of police harassment by the almost exclusively Protestant RUC and Ulster Special Constabulary (B Specials).

The divide between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland had little to do with theological differences but instead was grounded in culture and politics. Neither Irish history nor the Irish language was taught in schools in Northern Ireland, it was illegal to fly the flag of the Irish republic, and from 1956 to 1974 Sinn Féin, the party of Irish republicanism, also was banned in Northern Ireland. Catholics by and large identified as Irish and sought the incorporation of Northern Ireland into the Irish state. The great bulk of Protestants saw themselves as British and feared that they would lose their culture and privilege if Northern Ireland were subsumed by the republic. They expressed their partisan solidarity through involvement with Protestant unionist fraternal organizations such as the Orange Order, which found its inspiration in the victory of King William III (William of Orange) at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 over his deposed Catholic predecessor, James II, whose siege of the Protestant community of Londonderry had earlier been broken by William. Despite these tensions, for 40 or so years after partition the status of unionist-dominated Northern Ireland was relatively stable.

Recognizing that any attempt to reinvigorate Northern Ireland’s declining industrial economy in the early 1960s would also need to address the province’s percolatingpolitical and social tensions, the newly elected prime minister of Northern Ireland, Terence O’Neill, not only reached out to the nationalist community but also, in early 1965, exchanged visits with Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Seán Lemass—a radical step, given that the republic’s constitution included an assertion of sovereignty over the whole island. Nevertheless, O’Neill’s efforts were seen as inadequate by nationalists and as too conciliatory by loyalists, including the Rev. Ian Paisley, who became one of the most vehement and influential representatives of unionist reaction.

Contrary to the policies of UUP governments that disadvantaged Catholics, the Education Act that the Northern Ireland Parliament passed into law in 1947 increased educational opportunities for all citizens of the province. As a result, the generation of well-educated Catholics who came of age in the 1960s had new expectations for more equitable treatment. At a time when political activism was on the rise in Europe—from the events of May 1968 in France to the Prague Spring—and when the American civil rights movement was making great strides, Catholic activists in Northern Ireland such as John Humeand Bernadette Devlin came together to form civil rightsgroups such as the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA).

Although more than one violently disrupted political march has been pointed to as the starting point of the Troubles, it can be argued that the catalyzing event occurred on October 5, 1968, in Derry, where a march had been organized by the NICRA to protest discrimination and gerrymandering. The march was banned when unionists announced that they would be staging a counterdemonstration, but the NICRA decided to carry out their protest anyway. Rioting then erupted after the RUC violently suppressed the marchers with batons and a water cannon.

Similarly inflammatory were the events surrounding a march held by loyalists in Londonderry on August 12, 1969. Two days of rioting that became known as the Battle of Bogside (after the Catholic area in which the confrontation occurred) stemmed from the escalating clash between nationalists and the RUC, which was acting as a buffer between loyalist marchers and Catholic residents of the area. Rioting in support of the nationalists then erupted in Belfast and elsewhere, and the British army was dispatched to restore calm. Thereafter, violent confrontation only escalated, and the Troubles (a name that neither characterized the nature of the conflict nor assigned blame for it to one side or the other) had clearly begun.

Initially, the nationalists welcomed the British army as protectors and as a balance for the Protestant-leaning RUC. In time, however, the army would be viewed by nationalists as another version of the enemy, especially after its aggressive efforts to disarm republican paramilitaries. In the process, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) became the defender of the nationalist cause. From its base in Ireland(which had formally left the Commonwealth in 1949), the IRA had mounted an ineffectual guerrilla effort in support of Northern Ireland’s nationalists from 1956 to 1962, but, as the 1960s progressed, the IRA became less concerned with affairs in the north than with advancing a Marxist political agenda. As a result, a splinter group, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provos), which was prepared to use force to bring about unification, emerged as the champion of Northern Ireland’s nationalists. (The Official IRA would conduct operations in support of the republicans in Northern Ireland until undertaking a cease-fire in 1972, after which it effectively ceded the title of the IRA in the north to the Provos.) Believing that their fight was a continuation of the Irish War of Independence, the Provos adopted the tactics of guerrilla warfare, financed partly by members of the Irish diaspora in the United States and later supplied with arms and munitions by the government of Libyan strongman Muammar al-Qaddafi. Unionists also took up arms, swelling the numbers of loyalist paramilitary organizations, most notably the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and Ulster Defence Association UDA).

In an attempt to address nationalist grievances, electoral boundaries were redrawn more fairly, efforts were made to rectify discrimination in housing and public employment, and the B Specials were decommissioned. At the same time, the government of Northern Ireland responded to the growing unrest by introducing increasingly stringent security measures, including internment (detention without trial). The overwhelming majority of those arrested, however, were nationalists.

As the 1970s progressed, rioting became more common in Belfast and Derry, bombings of public places (by both loyalists and republicans) increased, and both sides of the conflict perpetrated violent, deadly atrocities. Barbed wire laid by British soldiers to separate the sectarian communitiesevolved into brick and steel “peace walls,” some of which stood 45 feet (14 metres) high, segregating loyalist and republican enclaves, most famously the Falls Road Catholic community and the Shankill Protestant community of Belfast.

On January 30, 1972, the conflict reached a new level of intensity when British paratroopers fired on Catholic civil rights demonstrators in Londonderry, killing 13 and injuring 14 others (one of whom later died). The incident, which became known as “Bloody Sunday,” contributed to a spike in Provos recruitment and would remain controversial for decades, hinging on the question of which side fired first. In 2010 the Saville Report , the final pronouncement of a British government inquiry into the event, concluded that none of the victims had posed a threat to the troops and that their shooting had been unjustified. British Prime Minister David Cameron responded to the report by issuing a landmark apology for the shooting:

There is no point in trying to soften or equivocate what is in this report. It is clear from the tribunal’s authoritative conclusions that the events of Bloody Sunday were in no way justified….What happened should never, ever have happened….Some members of our armed forces acted wrongly. The government is ultimately responsible for the conduct of the armed forces and for that, on behalf of the government, indeed, on behalf of our country, I am deeply sorry.

In all, more than 480 people were killed as a result of the conflict in Northern Ireland in 1972, which proved to be the deadliest single year in the Troubles. That total included more than 100 fatalities for the British army, as the IRA escalated its onslaught. On July 21, “Bloody Friday,” nine people were killed and scores were injured when some two dozen bombs were detonated by the Provos in Belfast. Earlier, in March, frustrated with the Northern Ireland government’s failure to calm the situation, the British government suspended the Northern Ireland Parliament and reinstituted direct rule by Westminster.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, the IRA shifted the emphasis of its “Long War” from direct engagements with British troops to smaller-scale secretive operations, including the bombing of cities in Britain—a change of tactics the British military described as a shift from “insurgency” to “terrorism.” Similarly, the loyalist groups began setting off bombs in Ireland. Meanwhile, paramilitary violence at mid-decade (1974–76) resulted in the civilian deaths of some 370 Catholics and 88 Protestants.

A glimmer of hope was offered by the Sunningdale Agreement , named for the English city in which it was negotiated in 1973. That agreement led to the creation of a new Northern Ireland Assembly, with proportional representation for all parties, and to the establishment of a Council of Ireland, which was to provide a role for Ireland in the affairs of Northern Ireland. Frustrated by the diminution of their political power and furious at the participation of the republic, loyalists scuttled the power-sharing plan with a general strike that brought the province to a halt in May 1974 and eventually forced a return to direct rule, which remained in place for some 25 years.

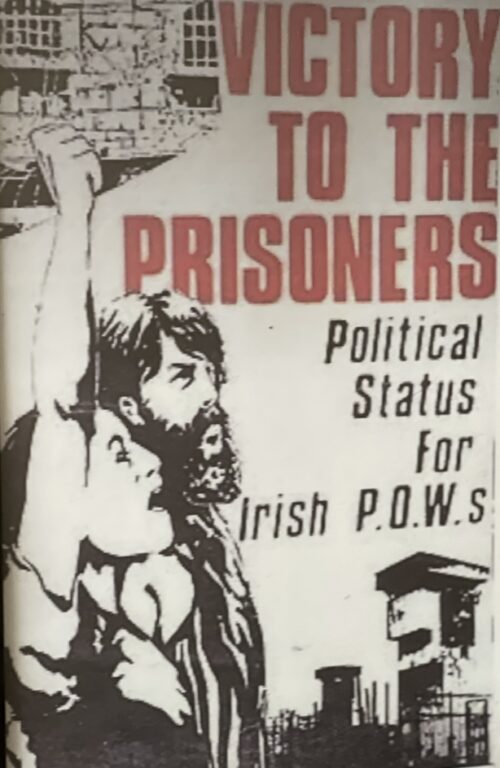

For the remainder of the decade, violence ebbed and flowed, cease-fires lingered and lapsed, and tit-for-tat bombings and assassinations continued, including the high-profile killing at sea in August 1979 of Lord Mountbatten, a relative of both Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip. In 1976 the opening of the specially designed Maze prison brought with it a shift in the treatment of IRA inmates from that of prisoners of war to that of common criminals. Seeking a return to their Special Category Status, the prisoners struck back, first staging the “blanket protest,” in which they refused to put on prison uniforms and instead wore only blankets, and then, in 1978, the “dirty protest,” in which inmates smeared the walls of their cells with excrement. The government of recently elected Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher refused to buckle, even in the face of hunger strikes in 1980–81 that led to the deaths of 10 prisoners, including Bobby Sands, who had won a seat in the British Parliament while incarcerated and fasting.

Sands’s election helped convince Sinn Féin, then operating as the political wing of the IRA, that the struggle for unification should be pursued at the ballot box as well as with the Armalite rifle. In June 1983 Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams won a seat in Parliament representing West Belfast, though he refused to take it to avoid taking the compulsory oath of loyalty to the British queen.

In October 1984 an IRA bomb attack on the Conservative Party Conference in Brighton, England, took five lives and threatened that of Thatcher. Though she remained steadfast in the face of this attack, it was the “Iron Lady” who in November 1985 joined Irish Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald in signing the Anglo-Irish Agreement, under which both countries guaranteed that any change in the status of Northern Ireland would come about only with the consent of the majority of the people of Northern Ireland. The accordalso established the Intergovernmental Conference, which gave Ireland a consultative role in the political and security affairs of Northern Ireland for the first time. Finally, the agreement stipulated that power would be devolved back upon the government of Northern Ireland only if unionists and nationalists participated in power sharing.

The loyalists’ vehement opposition to the agreement included the resignation of all 15 unionist members of the House of Commons and a ramping up of violence. In the meantime, IRA bombings in London made headlines, and the reach of the British security forces extended to the killing of three Provos in Gibraltar. Behind the scenes, however, negotiations were underway. In 1993 British Prime Minister John Major and Irish Taoiseach Albert Reynolds issued the so-called Downing Street Declaration , which established a framework for all-party peace talks. A cease-fire declared by the Provos in 1994 and joined by the principal loyalist paramilitary groups fell apart in 1996 because Sinn Féin, which had replaced the more moderate Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) as the leading nationalist party, had been excluded from peace talks because of the IRA’s continuing bombing campaign. Nevertheless, the unionists were at the table, prepared to consider a solution that included the participation of the republic of Ireland. After the IRA resumed its cease-fire in 1997, Sinn Féin was welcomed back to the talks, which now included the British and Irish governments, the SDLP, the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland, the UUP, and the Ulster Democratic Party, among others, though not the Paisley-led DUP, which was protesting the inclusion of Sinn Féin.

Those talks, mediated by former U.S. senator George Mitchell, led to the Good Friday Agreement (Belfast Agreement), reached April 10, 1998. That landmark accordprovided for the creation of a power-sharing Northern Ireland Assembly, established an institutional arrangement for cross-border cooperation between the governments of Ireland and Northern Ireland on a range of issues, and lay the groundwork for continued consultation between the British and Irish governments. On May 22 Ireland and Northern Ireland held a joint referendum on the agreement, which was approved by 94 percent of those who voted in the republic and 71 percent of those voting in Northern Ireland, where Catholic approval of the accord (96 percent) was much higher than Protestant assent (52 per cent). Nonetheless, it was an IRA splinter group, the Real Irish Republican Army, which most dramatically violated the spirit of the agreement, with a bombing in Omagh in August that took 29 lives.

Elections for the new Assembly were held in June, but the IRA’s failure to decommission delayed the formation of the power-sharing Northern Ireland Executive until December 1999, when the IRA promised to fulfill its obligation to disarm. That month the republic of Ireland modified its constitution, removing its territorial claims to the whole of the island, and the United Kingdom yielded direct rule of Northern Ireland. Ostensibly the Troubles had come to end, but, though Northern Ireland began its most tranquil era in a generation, the peace was fragile. Sectarian antagonism persisted, the process of decommissioning was slow on both sides, and the rolling out of the new institutions was fitful, resulting in suspensions of devolution and the reimposition of direct rule.

In July 2005, however, the IRA announced that it had ordered all its units to “dump arms,” would henceforth pursue its goals only through peaceful means, and would work with international inspectors “to verifiably put its arms beyond use.” At a press conference in September, a spokesman for the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning stated, “We are satisfied that the arms decommissioned represent the totality of the IRA’s arsenal.” Decommissioning by unionist paramilitaries and other republican groups followed..

The Troubles, also called Northern Ireland conflict, violent sectarian conflict from about 1968 to 1998 in Northern Irelandbetween the overwhelmingly Protestantunionists (loyalists), who desired the province to remain part of the United Kingdom, and the overwhelmingly Roman Catholic nationalists (republicans), who wanted Northern Ireland to become part of the republic of Ireland. The other major players in the conflict were the British army, Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR; from 1992 called the Royal Irish Regiment), and their avowed purpose was to play a peacekeeping role, most prominently between the nationalist Irish Republican Army(IRA), which viewed the conflict as a guerrilla war for national independence, and the unionist paramilitary forces, which characterized the IRA’s aggression as terrorism. Marked by street fighting, sensational bombings, sniper attacks, roadblocks, and internment without trial, the confrontation had the characteristics of a civil war, notwithstanding its textbook categorization as a “low-intensity conflict.” Some 3,600 people were killed and more than 30,000 more were wounded before a peaceful solution, which involved the governments of both the United Kingdom and Ireland, was effectively reached in 1998, leading to a power-sharing arrangement in the Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont.

The story of the Troubles is inextricably entwined with the history of Ireland as whole and, as such, can be seen as stemming from the first British incursion on the island, the Anglo-Norman invasion of the late 12th century, which left a wave of settlers whose descendants became known as the “Old English.” Thereafter, for nearly eight centuries, England and then Great Britain as a whole would dominate affairs in Ireland. Colonizing British landlords widely displaced Irish landholders. The most successful of these “plantations” began taking hold in the early 17th century in Ulster, the northernmost of Ireland’s four traditional provinces, previously a centre of rebellion, where the planters included English and Scottish tenants as well as British landlords. Because of the plantation of Ulster, as Irish history unfolded—with the struggle for the emancipation of the island’s Catholic majority under the supremacy of the Protestant ascendancy, along with the Irish nationalist pursuit of Home Rule and then independence after the island’s formal union with Great Britain in 1801—Ulster developed as a region where the Protestant settlers outnumbered the indigenousIrish. Unlike earlier English settlers, most of the 17th-century English and Scottish settlers and their descendants did not assimilate with the Irish. Instead, they held on tightly to British identity and remained steadfastly loyal to the British crown.

Of the nine modern counties that constituted Ulster in the early 20th century, four—Antrim, Down, Armagh, and Londonderry (Derry)—had significant Protestant loyalist majorities; two—Fermanagh and Tyrone—had small Catholic nationalist majorities; and three—Donegal, Cavan, and Monaghan—had significant Catholic nationalist majorities. In 1920, during the Irish War of Independence (1919–21), the British Parliament, responding largely to the wishes of Ulster loyalists, enacted the Government of Ireland Act , which divided the island into two self-governing areas with devolved Home Rule-like powers. What would come to be known as Northern Ireland was formed by Ulster’s four majority loyalist counties along with Fermanagh and Tyrone. Donegal, Cavan, and Monaghan were combined with the island’s remaining 23 counties to form southern Ireland. The Anglo-Irish Treaty that ended the War of Independence then created the Irish Free State in the south, giving it dominion status within the British Empire. It also allowed Northern Ireland the option of remaining outside of the Free State, which it unsurprisingly chose to do.

Thus, in 1922 Northern Ireland began functioning as a self-governing region of the United Kingdom. Two-thirds of its population (about one million people) was Protestant and about one-third (roughly 500,000 people) was Catholic. Well before partition, Northern Ireland, particularly Belfast, had attracted economic migrants from elsewhere in Ireland seeking employment in its flourishing linen-making and shipbuilding industries. The best jobs had gone to Protestants, but the humming local economy still provided work for Catholics. Over and above the long-standing dominance of Northern Ireland politics that resulted for the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) by virtue of the Protestants’ sheer numerical advantage, loyalist control of local politics was ensured by the gerrymandering of electoral districts that concentrated and minimized Catholic representation. Moreover, by restricting the franchise to ratepayers (the taxpaying heads of households) and their spouses, representation was further limited for Catholic households, which tended to be larger (and more likely to include unemployed adult children) than their Protestant counterparts. Those who paid rates for more than one residence (more likely to be Protestants) were granted an additional vote for each ward in which they held property (up to six votes). Catholics argued that they were discriminated against when it came to the allocation of public housing, appointments to public service jobs, and government investment in neighbourhoods. They were also more likely to be the subjects of police harassment by the almost exclusively Protestant RUC and Ulster Special Constabulary (B Specials).

The divide between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland had little to do with theological differences but instead was grounded in culture and politics. Neither Irish history nor the Irish language was taught in schools in Northern Ireland, it was illegal to fly the flag of the Irish republic, and from 1956 to 1974 Sinn Féin, the party of Irish republicanism, also was banned in Northern Ireland. Catholics by and large identified as Irish and sought the incorporation of Northern Ireland into the Irish state. The great bulk of Protestants saw themselves as British and feared that they would lose their culture and privilege if Northern Ireland were subsumed by the republic. They expressed their partisan solidarity through involvement with Protestant unionist fraternal organizations such as the Orange Order, which found its inspiration in the victory of King William III (William of Orange) at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 over his deposed Catholic predecessor, James II, whose siege of the Protestant community of Londonderry had earlier been broken by William. Despite these tensions, for 40 or so years after partition the status of unionist-dominated Northern Ireland was relatively stable.

Recognizing that any attempt to reinvigorate Northern Ireland’s declining industrial economy in the early 1960s would also need to address the province’s percolatingpolitical and social tensions, the newly elected prime minister of Northern Ireland, Terence O’Neill, not only reached out to the nationalist community but also, in early 1965, exchanged visits with Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Seán Lemass—a radical step, given that the republic’s constitution included an assertion of sovereignty over the whole island. Nevertheless, O’Neill’s efforts were seen as inadequate by nationalists and as too conciliatory by loyalists, including the Rev. Ian Paisley, who became one of the most vehement and influential representatives of unionist reaction.

Contrary to the policies of UUP governments that disadvantaged Catholics, the Education Act that the Northern Ireland Parliament passed into law in 1947 increased educational opportunities for all citizens of the province. As a result, the generation of well-educated Catholics who came of age in the 1960s had new expectations for more equitable treatment. At a time when political activism was on the rise in Europe—from the events of May 1968 in France to the Prague Spring—and when the American civil rights movement was making great strides, Catholic activists in Northern Ireland such as John Humeand Bernadette Devlin came together to form civil rightsgroups such as the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA).

Although more than one violently disrupted political march has been pointed to as the starting point of the Troubles, it can be argued that the catalyzing event occurred on October 5, 1968, in Derry, where a march had been organized by the NICRA to protest discrimination and gerrymandering. The march was banned when unionists announced that they would be staging a counterdemonstration, but the NICRA decided to carry out their protest anyway. Rioting then erupted after the RUC violently suppressed the marchers with batons and a water cannon.

Similarly inflammatory were the events surrounding a march held by loyalists in Londonderry on August 12, 1969. Two days of rioting that became known as the Battle of Bogside (after the Catholic area in which the confrontation occurred) stemmed from the escalating clash between nationalists and the RUC, which was acting as a buffer between loyalist marchers and Catholic residents of the area. Rioting in support of the nationalists then erupted in Belfast and elsewhere, and the British army was dispatched to restore calm. Thereafter, violent confrontation only escalated, and the Troubles (a name that neither characterized the nature of the conflict nor assigned blame for it to one side or the other) had clearly begun.

Initially, the nationalists welcomed the British army as protectors and as a balance for the Protestant-leaning RUC. In time, however, the army would be viewed by nationalists as another version of the enemy, especially after its aggressive efforts to disarm republican paramilitaries. In the process, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) became the defender of the nationalist cause. From its base in Ireland(which had formally left the Commonwealth in 1949), the IRA had mounted an ineffectual guerrilla effort in support of Northern Ireland’s nationalists from 1956 to 1962, but, as the 1960s progressed, the IRA became less concerned with affairs in the north than with advancing a Marxist political agenda. As a result, a splinter group, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provos), which was prepared to use force to bring about unification, emerged as the champion of Northern Ireland’s nationalists. (The Official IRA would conduct operations in support of the republicans in Northern Ireland until undertaking a cease-fire in 1972, after which it effectively ceded the title of the IRA in the north to the Provos.) Believing that their fight was a continuation of the Irish War of Independence, the Provos adopted the tactics of guerrilla warfare, financed partly by members of the Irish diaspora in the United States and later supplied with arms and munitions by the government of Libyan strongman Muammar al-Qaddafi. Unionists also took up arms, swelling the numbers of loyalist paramilitary organizations, most notably the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and Ulster Defence Association UDA).

In an attempt to address nationalist grievances, electoral boundaries were redrawn more fairly, efforts were made to rectify discrimination in housing and public employment, and the B Specials were decommissioned. At the same time, the government of Northern Ireland responded to the growing unrest by introducing increasingly stringent security measures, including internment (detention without trial). The overwhelming majority of those arrested, however, were nationalists.

As the 1970s progressed, rioting became more common in Belfast and Derry, bombings of public places (by both loyalists and republicans) increased, and both sides of the conflict perpetrated violent, deadly atrocities. Barbed wire laid by British soldiers to separate the sectarian communitiesevolved into brick and steel “peace walls,” some of which stood 45 feet (14 metres) high, segregating loyalist and republican enclaves, most famously the Falls Road Catholic community and the Shankill Protestant community of Belfast.

On January 30, 1972, the conflict reached a new level of intensity when British paratroopers fired on Catholic civil rights demonstrators in Londonderry, killing 13 and injuring 14 others (one of whom later died). The incident, which became known as “Bloody Sunday,” contributed to a spike in Provos recruitment and would remain controversial for decades, hinging on the question of which side fired first. In 2010 the Saville Report , the final pronouncement of a British government inquiry into the event, concluded that none of the victims had posed a threat to the troops and that their shooting had been unjustified. British Prime Minister David Cameron responded to the report by issuing a landmark apology for the shooting:

There is no point in trying to soften or equivocate what is in this report. It is clear from the tribunal’s authoritative conclusions that the events of Bloody Sunday were in no way justified….What happened should never, ever have happened….Some members of our armed forces acted wrongly. The government is ultimately responsible for the conduct of the armed forces and for that, on behalf of the government, indeed, on behalf of our country, I am deeply sorry.

In all, more than 480 people were killed as a result of the conflict in Northern Ireland in 1972, which proved to be the deadliest single year in the Troubles. That total included more than 100 fatalities for the British army, as the IRA escalated its onslaught. On July 21, “Bloody Friday,” nine people were killed and scores were injured when some two dozen bombs were detonated by the Provos in Belfast. Earlier, in March, frustrated with the Northern Ireland government’s failure to calm the situation, the British government suspended the Northern Ireland Parliament and reinstituted direct rule by Westminster.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, the IRA shifted the emphasis of its “Long War” from direct engagements with British troops to smaller-scale secretive operations, including the bombing of cities in Britain—a change of tactics the British military described as a shift from “insurgency” to “terrorism.” Similarly, the loyalist groups began setting off bombs in Ireland. Meanwhile, paramilitary violence at mid-decade (1974–76) resulted in the civilian deaths of some 370 Catholics and 88 Protestants.

A glimmer of hope was offered by the Sunningdale Agreement , named for the English city in which it was negotiated in 1973. That agreement led to the creation of a new Northern Ireland Assembly, with proportional representation for all parties, and to the establishment of a Council of Ireland, which was to provide a role for Ireland in the affairs of Northern Ireland. Frustrated by the diminution of their political power and furious at the participation of the republic, loyalists scuttled the power-sharing plan with a general strike that brought the province to a halt in May 1974 and eventually forced a return to direct rule, which remained in place for some 25 years.

For the remainder of the decade, violence ebbed and flowed, cease-fires lingered and lapsed, and tit-for-tat bombings and assassinations continued, including the high-profile killing at sea in August 1979 of Lord Mountbatten, a relative of both Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip. In 1976 the opening of the specially designed Maze prison brought with it a shift in the treatment of IRA inmates from that of prisoners of war to that of common criminals. Seeking a return to their Special Category Status, the prisoners struck back, first staging the “blanket protest,” in which they refused to put on prison uniforms and instead wore only blankets, and then, in 1978, the “dirty protest,” in which inmates smeared the walls of their cells with excrement. The government of recently elected Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher refused to buckle, even in the face of hunger strikes in 1980–81 that led to the deaths of 10 prisoners, including Bobby Sands, who had won a seat in the British Parliament while incarcerated and fasting.

Sands’s election helped convince Sinn Féin, then operating as the political wing of the IRA, that the struggle for unification should be pursued at the ballot box as well as with the Armalite rifle. In June 1983 Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams won a seat in Parliament representing West Belfast, though he refused to take it to avoid taking the compulsory oath of loyalty to the British queen.

In October 1984 an IRA bomb attack on the Conservative Party Conference in Brighton, England, took five lives and threatened that of Thatcher. Though she remained steadfast in the face of this attack, it was the “Iron Lady” who in November 1985 joined Irish Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald in signing the Anglo-Irish Agreement, under which both countries guaranteed that any change in the status of Northern Ireland would come about only with the consent of the majority of the people of Northern Ireland. The accordalso established the Intergovernmental Conference, which gave Ireland a consultative role in the political and security affairs of Northern Ireland for the first time. Finally, the agreement stipulated that power would be devolved back upon the government of Northern Ireland only if unionists and nationalists participated in power sharing.

The loyalists’ vehement opposition to the agreement included the resignation of all 15 unionist members of the House of Commons and a ramping up of violence. In the meantime, IRA bombings in London made headlines, and the reach of the British security forces extended to the killing of three Provos in Gibraltar. Behind the scenes, however, negotiations were underway. In 1993 British Prime Minister John Major and Irish Taoiseach Albert Reynolds issued the so-called Downing Street Declaration , which established a framework for all-party peace talks. A cease-fire declared by the Provos in 1994 and joined by the principal loyalist paramilitary groups fell apart in 1996 because Sinn Féin, which had replaced the more moderate Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) as the leading nationalist party, had been excluded from peace talks because of the IRA’s continuing bombing campaign. Nevertheless, the unionists were at the table, prepared to consider a solution that included the participation of the republic of Ireland. After the IRA resumed its cease-fire in 1997, Sinn Féin was welcomed back to the talks, which now included the British and Irish governments, the SDLP, the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland, the UUP, and the Ulster Democratic Party, among others, though not the Paisley-led DUP, which was protesting the inclusion of Sinn Féin.

Those talks, mediated by former U.S. senator George Mitchell, led to the Good Friday Agreement (Belfast Agreement), reached April 10, 1998. That landmark accordprovided for the creation of a power-sharing Northern Ireland Assembly, established an institutional arrangement for cross-border cooperation between the governments of Ireland and Northern Ireland on a range of issues, and lay the groundwork for continued consultation between the British and Irish governments. On May 22 Ireland and Northern Ireland held a joint referendum on the agreement, which was approved by 94 percent of those who voted in the republic and 71 percent of those voting in Northern Ireland, where Catholic approval of the accord (96 percent) was much higher than Protestant assent (52 per cent). Nonetheless, it was an IRA splinter group, the Real Irish Republican Army, which most dramatically violated the spirit of the agreement, with a bombing in Omagh in August that took 29 lives.

Elections for the new Assembly were held in June, but the IRA’s failure to decommission delayed the formation of the power-sharing Northern Ireland Executive until December 1999, when the IRA promised to fulfill its obligation to disarm. That month the republic of Ireland modified its constitution, removing its territorial claims to the whole of the island, and the United Kingdom yielded direct rule of Northern Ireland. Ostensibly the Troubles had come to end, but, though Northern Ireland began its most tranquil era in a generation, the peace was fragile. Sectarian antagonism persisted, the process of decommissioning was slow on both sides, and the rolling out of the new institutions was fitful, resulting in suspensions of devolution and the reimposition of direct rule.

In July 2005, however, the IRA announced that it had ordered all its units to “dump arms,” would henceforth pursue its goals only through peaceful means, and would work with international inspectors “to verifiably put its arms beyond use.” At a press conference in September, a spokesman for the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning stated, “We are satisfied that the arms decommissioned represent the totality of the IRA’s arsenal.” Decommissioning by unionist paramilitaries and other republican groups followed..

The Troubles, also called Northern Ireland conflict, violent sectarian conflict from about 1968 to 1998 in Northern Irelandbetween the overwhelmingly Protestantunionists (loyalists), who desired the province to remain part of the United Kingdom, and the overwhelmingly Roman Catholic nationalists (republicans), who wanted Northern Ireland to become part of the republic of Ireland. The other major players in the conflict were the British army, Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR; from 1992 called the Royal Irish Regiment), and their avowed purpose was to play a peacekeeping role, most prominently between the nationalist Irish Republican Army(IRA), which viewed the conflict as a guerrilla war for national independence, and the unionist paramilitary forces, which characterized the IRA’s aggression as terrorism. Marked by street fighting, sensational bombings, sniper attacks, roadblocks, and internment without trial, the confrontation had the characteristics of a civil war, notwithstanding its textbook categorization as a “low-intensity conflict.” Some 3,600 people were killed and more than 30,000 more were wounded before a peaceful solution, which involved the governments of both the United Kingdom and Ireland, was effectively reached in 1998, leading to a power-sharing arrangement in the Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont.

The story of the Troubles is inextricably entwined with the history of Ireland as whole and, as such, can be seen as stemming from the first British incursion on the island, the Anglo-Norman invasion of the late 12th century, which left a wave of settlers whose descendants became known as the “Old English.” Thereafter, for nearly eight centuries, England and then Great Britain as a whole would dominate affairs in Ireland. Colonizing British landlords widely displaced Irish landholders. The most successful of these “plantations” began taking hold in the early 17th century in Ulster, the northernmost of Ireland’s four traditional provinces, previously a centre of rebellion, where the planters included English and Scottish tenants as well as British landlords. Because of the plantation of Ulster, as Irish history unfolded—with the struggle for the emancipation of the island’s Catholic majority under the supremacy of the Protestant ascendancy, along with the Irish nationalist pursuit of Home Rule and then independence after the island’s formal union with Great Britain in 1801—Ulster developed as a region where the Protestant settlers outnumbered the indigenousIrish. Unlike earlier English settlers, most of the 17th-century English and Scottish settlers and their descendants did not assimilate with the Irish. Instead, they held on tightly to British identity and remained steadfastly loyal to the British crown.

Of the nine modern counties that constituted Ulster in the early 20th century, four—Antrim, Down, Armagh, and Londonderry (Derry)—had significant Protestant loyalist majorities; two—Fermanagh and Tyrone—had small Catholic nationalist majorities; and three—Donegal, Cavan, and Monaghan—had significant Catholic nationalist majorities. In 1920, during the Irish War of Independence (1919–21), the British Parliament, responding largely to the wishes of Ulster loyalists, enacted the Government of Ireland Act , which divided the island into two self-governing areas with devolved Home Rule-like powers. What would come to be known as Northern Ireland was formed by Ulster’s four majority loyalist counties along with Fermanagh and Tyrone. Donegal, Cavan, and Monaghan were combined with the island’s remaining 23 counties to form southern Ireland. The Anglo-Irish Treaty that ended the War of Independence then created the Irish Free State in the south, giving it dominion status within the British Empire. It also allowed Northern Ireland the option of remaining outside of the Free State, which it unsurprisingly chose to do.

Thus, in 1922 Northern Ireland began functioning as a self-governing region of the United Kingdom. Two-thirds of its population (about one million people) was Protestant and about one-third (roughly 500,000 people) was Catholic. Well before partition, Northern Ireland, particularly Belfast, had attracted economic migrants from elsewhere in Ireland seeking employment in its flourishing linen-making and shipbuilding industries. The best jobs had gone to Protestants, but the humming local economy still provided work for Catholics. Over and above the long-standing dominance of Northern Ireland politics that resulted for the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) by virtue of the Protestants’ sheer numerical advantage, loyalist control of local politics was ensured by the gerrymandering of electoral districts that concentrated and minimized Catholic representation. Moreover, by restricting the franchise to ratepayers (the taxpaying heads of households) and their spouses, representation was further limited for Catholic households, which tended to be larger (and more likely to include unemployed adult children) than their Protestant counterparts. Those who paid rates for more than one residence (more likely to be Protestants) were granted an additional vote for each ward in which they held property (up to six votes). Catholics argued that they were discriminated against when it came to the allocation of public housing, appointments to public service jobs, and government investment in neighbourhoods. They were also more likely to be the subjects of police harassment by the almost exclusively Protestant RUC and Ulster Special Constabulary (B Specials).

The divide between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland had little to do with theological differences but instead was grounded in culture and politics. Neither Irish history nor the Irish language was taught in schools in Northern Ireland, it was illegal to fly the flag of the Irish republic, and from 1956 to 1974 Sinn Féin, the party of Irish republicanism, also was banned in Northern Ireland. Catholics by and large identified as Irish and sought the incorporation of Northern Ireland into the Irish state. The great bulk of Protestants saw themselves as British and feared that they would lose their culture and privilege if Northern Ireland were subsumed by the republic. They expressed their partisan solidarity through involvement with Protestant unionist fraternal organizations such as the Orange Order, which found its inspiration in the victory of King William III (William of Orange) at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 over his deposed Catholic predecessor, James II, whose siege of the Protestant community of Londonderry had earlier been broken by William. Despite these tensions, for 40 or so years after partition the status of unionist-dominated Northern Ireland was relatively stable.

Recognizing that any attempt to reinvigorate Northern Ireland’s declining industrial economy in the early 1960s would also need to address the province’s percolatingpolitical and social tensions, the newly elected prime minister of Northern Ireland, Terence O’Neill, not only reached out to the nationalist community but also, in early 1965, exchanged visits with Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Seán Lemass—a radical step, given that the republic’s constitution included an assertion of sovereignty over the whole island. Nevertheless, O’Neill’s efforts were seen as inadequate by nationalists and as too conciliatory by loyalists, including the Rev. Ian Paisley, who became one of the most vehement and influential representatives of unionist reaction.

Contrary to the policies of UUP governments that disadvantaged Catholics, the Education Act that the Northern Ireland Parliament passed into law in 1947 increased educational opportunities for all citizens of the province. As a result, the generation of well-educated Catholics who came of age in the 1960s had new expectations for more equitable treatment. At a time when political activism was on the rise in Europe—from the events of May 1968 in France to the Prague Spring—and when the American civil rights movement was making great strides, Catholic activists in Northern Ireland such as John Humeand Bernadette Devlin came together to form civil rightsgroups such as the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA).

Although more than one violently disrupted political march has been pointed to as the starting point of the Troubles, it can be argued that the catalyzing event occurred on October 5, 1968, in Derry, where a march had been organized by the NICRA to protest discrimination and gerrymandering. The march was banned when unionists announced that they would be staging a counterdemonstration, but the NICRA decided to carry out their protest anyway. Rioting then erupted after the RUC violently suppressed the marchers with batons and a water cannon.

Similarly inflammatory were the events surrounding a march held by loyalists in Londonderry on August 12, 1969. Two days of rioting that became known as the Battle of Bogside (after the Catholic area in which the confrontation occurred) stemmed from the escalating clash between nationalists and the RUC, which was acting as a buffer between loyalist marchers and Catholic residents of the area. Rioting in support of the nationalists then erupted in Belfast and elsewhere, and the British army was dispatched to restore calm. Thereafter, violent confrontation only escalated, and the Troubles (a name that neither characterized the nature of the conflict nor assigned blame for it to one side or the other) had clearly begun.

Initially, the nationalists welcomed the British army as protectors and as a balance for the Protestant-leaning RUC. In time, however, the army would be viewed by nationalists as another version of the enemy, especially after its aggressive efforts to disarm republican paramilitaries. In the process, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) became the defender of the nationalist cause. From its base in Ireland(which had formally left the Commonwealth in 1949), the IRA had mounted an ineffectual guerrilla effort in support of Northern Ireland’s nationalists from 1956 to 1962, but, as the 1960s progressed, the IRA became less concerned with affairs in the north than with advancing a Marxist political agenda. As a result, a splinter group, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provos), which was prepared to use force to bring about unification, emerged as the champion of Northern Ireland’s nationalists. (The Official IRA would conduct operations in support of the republicans in Northern Ireland until undertaking a cease-fire in 1972, after which it effectively ceded the title of the IRA in the north to the Provos.) Believing that their fight was a continuation of the Irish War of Independence, the Provos adopted the tactics of guerrilla warfare, financed partly by members of the Irish diaspora in the United States and later supplied with arms and munitions by the government of Libyan strongman Muammar al-Qaddafi. Unionists also took up arms, swelling the numbers of loyalist paramilitary organizations, most notably the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and Ulster Defence Association UDA).

In an attempt to address nationalist grievances, electoral boundaries were redrawn more fairly, efforts were made to rectify discrimination in housing and public employment, and the B Specials were decommissioned. At the same time, the government of Northern Ireland responded to the growing unrest by introducing increasingly stringent security measures, including internment (detention without trial). The overwhelming majority of those arrested, however, were nationalists.

As the 1970s progressed, rioting became more common in Belfast and Derry, bombings of public places (by both loyalists and republicans) increased, and both sides of the conflict perpetrated violent, deadly atrocities. Barbed wire laid by British soldiers to separate the sectarian communitiesevolved into brick and steel “peace walls,” some of which stood 45 feet (14 metres) high, segregating loyalist and republican enclaves, most famously the Falls Road Catholic community and the Shankill Protestant community of Belfast.

On January 30, 1972, the conflict reached a new level of intensity when British paratroopers fired on Catholic civil rights demonstrators in Londonderry, killing 13 and injuring 14 others (one of whom later died). The incident, which became known as “Bloody Sunday,” contributed to a spike in Provos recruitment and would remain controversial for decades, hinging on the question of which side fired first. In 2010 the Saville Report , the final pronouncement of a British government inquiry into the event, concluded that none of the victims had posed a threat to the troops and that their shooting had been unjustified. British Prime Minister David Cameron responded to the report by issuing a landmark apology for the shooting:

There is no point in trying to soften or equivocate what is in this report. It is clear from the tribunal’s authoritative conclusions that the events of Bloody Sunday were in no way justified….What happened should never, ever have happened….Some members of our armed forces acted wrongly. The government is ultimately responsible for the conduct of the armed forces and for that, on behalf of the government, indeed, on behalf of our country, I am deeply sorry.

In all, more than 480 people were killed as a result of the conflict in Northern Ireland in 1972, which proved to be the deadliest single year in the Troubles. That total included more than 100 fatalities for the British army, as the IRA escalated its onslaught. On July 21, “Bloody Friday,” nine people were killed and scores were injured when some two dozen bombs were detonated by the Provos in Belfast. Earlier, in March, frustrated with the Northern Ireland government’s failure to calm the situation, the British government suspended the Northern Ireland Parliament and reinstituted direct rule by Westminster.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, the IRA shifted the emphasis of its “Long War” from direct engagements with British troops to smaller-scale secretive operations, including the bombing of cities in Britain—a change of tactics the British military described as a shift from “insurgency” to “terrorism.” Similarly, the loyalist groups began setting off bombs in Ireland. Meanwhile, paramilitary violence at mid-decade (1974–76) resulted in the civilian deaths of some 370 Catholics and 88 Protestants.

A glimmer of hope was offered by the Sunningdale Agreement , named for the English city in which it was negotiated in 1973. That agreement led to the creation of a new Northern Ireland Assembly, with proportional representation for all parties, and to the establishment of a Council of Ireland, which was to provide a role for Ireland in the affairs of Northern Ireland. Frustrated by the diminution of their political power and furious at the participation of the republic, loyalists scuttled the power-sharing plan with a general strike that brought the province to a halt in May 1974 and eventually forced a return to direct rule, which remained in place for some 25 years.