-

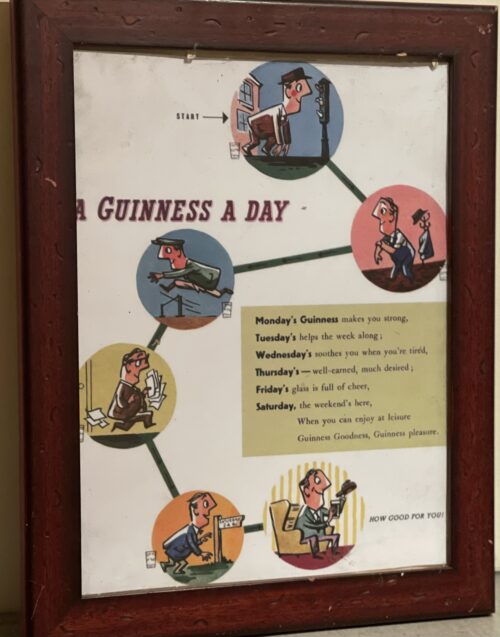

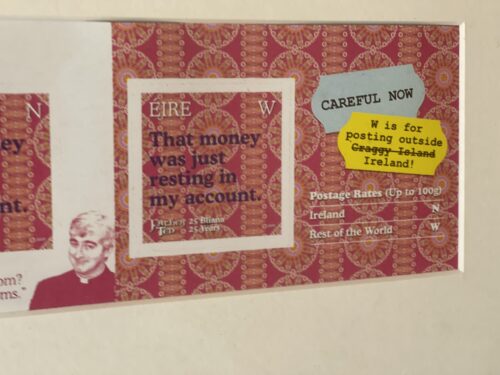

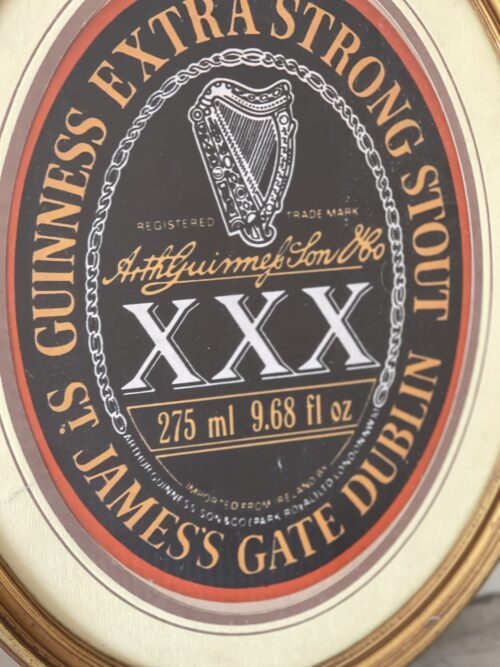

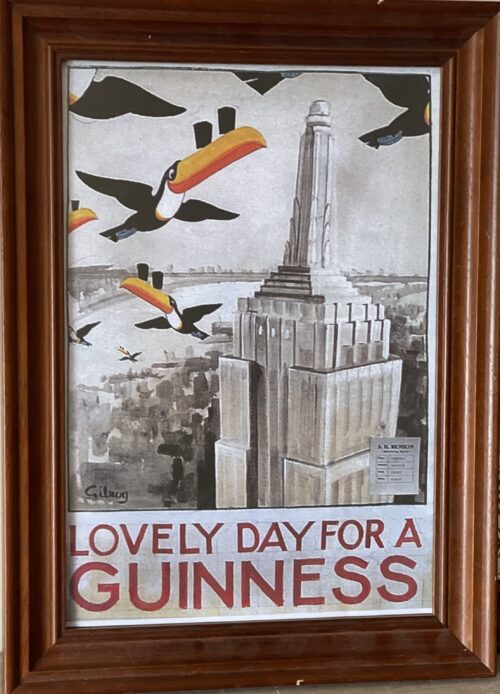

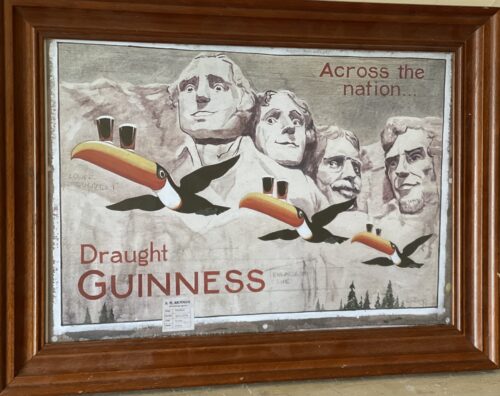

47cm x 37cm Limerick Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.”

47cm x 37cm Limerick Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” -

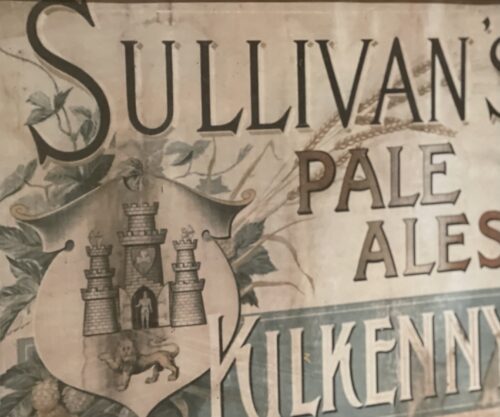

37cm x 47cm Limerick Sullivan’s Brewing Company opened for business over three hundred years ago in The Maltings on James’s Street, smack bang in the middle of Kilkenny City.

37cm x 47cm Limerick Sullivan’s Brewing Company opened for business over three hundred years ago in The Maltings on James’s Street, smack bang in the middle of Kilkenny City.Up until the early 1700s, brewing on a large scale was a rarity, this resulted in many small breweries springing up all around the country, with little or no consistency in the beer that was being produced. Back then, to guarantee that each pint was as good as the last, required brewing on a bigger, more exacting scale.

Enter Mr. Sullivan, a man of high morals, integrity and a good nose for great beer. Through his belief and hard work he established a brewery the likes of which had never been seen in Kilkenny. He only used the very best local ingredients and the very best brewing methods to ensure that every barrel of Sullivan’s Red Ale that left his brewery was as good as the one that had gone before.

Richard Sullivan was elected to represent the people of Kilkenny in the 1820s. This supposedly put one well-known Irish political figure’s nose well and truly out of joint – Daniel O’Connell.After one particularly heated parliamentary quarrel, O’Connell even called a boycott of Sullivan’s Ale by the people of Kilkenny. But you’ll know if you’ve ever had a pint of Sullivan’s Red Ale in front of you that it can be very hard to resist, and the boycott was soon called off.

Despite this rocky start, Richard and Daniel went on to become firm friends. So good in fact, that when O’Connell was stripped of his seat in Parliament due to some underhand dealings, Sullivan was one of the few who had his back. He wrote to Daniel and offered him his seat to ensure that O’Connell’s Catholic Emancipation Act would get through Parliament.

1802MIXING BUSINESS AND POLITICSGOOD WILL, KINDNESS AND HOT SOUP

1880 was the year of ‘The Great Sullivan’s Brewery Fire’, a day that has gone down in legend among the people of Kilkenny.The story goes that the Sullivan Family took the day off brewing to attend the funeral of a recently departed family friend in a Kilkenny hilltop chapel. Leaving a funeral before all the formalities were completed was the height of bad manners. The Sullivans could see the brewery ablaze from the hillside, but could do nothing about it.

As the first flames began to lick the outside of the brewery, the alarm was raised and the local fire brigade was sent for. But The Kilkenny Fire Brigade consisted of a few volunteers, a horse and a cart and a useless, leaking hose. Due to all their good deeds over the years, the Sullivans were a tremendously popular family in Kilkenny, so men, women and children from far and wide rallied together and grabbed the nearest buckets, pales and pots, filling them with water and battling the fire. Within an hour the fire was under control and the brewery was saved, all because a community came together.

1880A COMMUNITY WORKING TOGETH1918

BLACK SHEEP AND THE LOST WAGER

After Sullivan’s Brewery closed for the final time in the early 1900s the tales of the good deeds of this Sullivan Family began to fade into memory.

Over the coming decades, the independent breweries that were once synonymous with Kilkenny began to drop off one by one, until its final working brewery sadly closed its doors in 2013. However, there wasn’t long to wait for a change of fortunes for Kilkenny-brewed ale, as 2016 saw two great families coming together to return traditional Irish brewing to its spiritual home.

The Smithwick Family in partnership with direct descendants of the Sullivan Family had a vision to re-open the once-great brewery in the city where it all began. They enlisted the help of Ian Hamilton, one of Ireland’s most eminent contemporary master-brewers. Together they are bringing artisan brewing back to Kilkenny.

If people thought that brewing in Kilkenny was dead and buried, they are in for a rude awakening…

2016

TWO GREAT FAMILIES AND THE RETURN OF SULLIVANS

WE’RE BACK AND HERE TO STAY

-

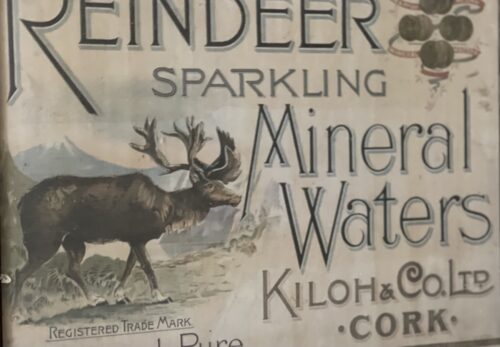

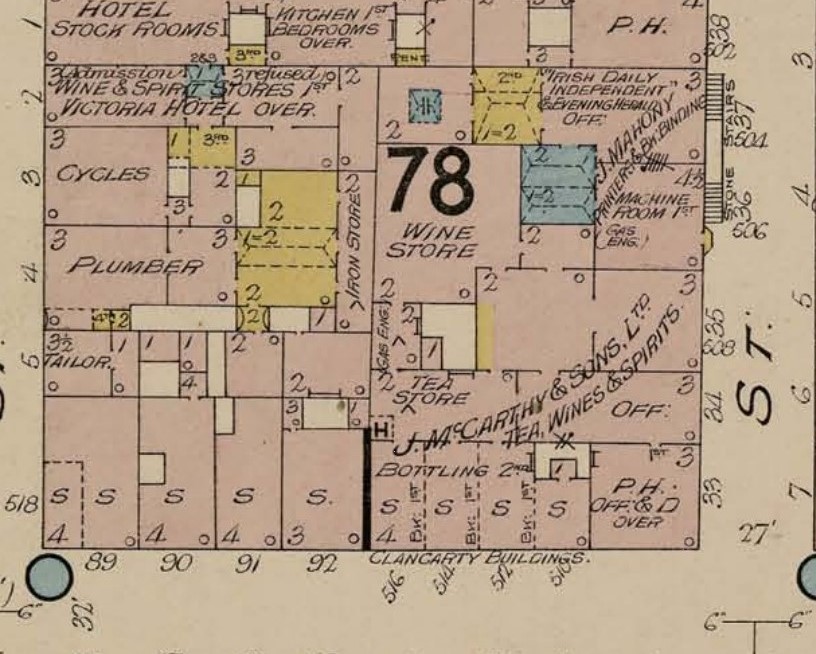

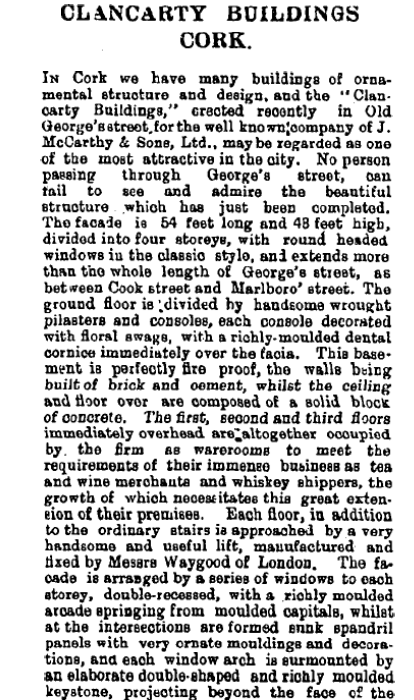

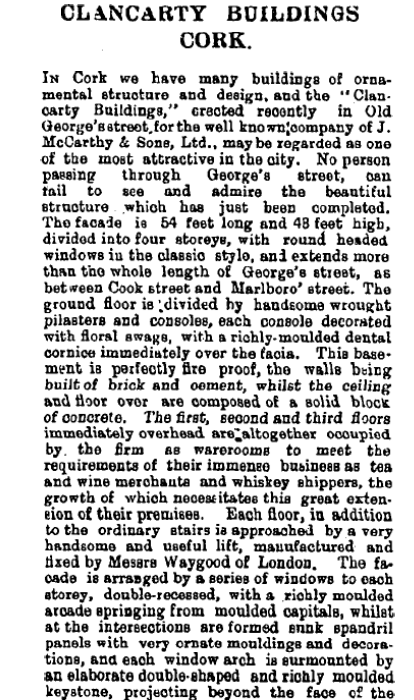

47cm x 37cm Limerick The building itself it is a terraced eight-bay four-storey late-Victorian commercial building, It was built across 1895 and 1896 for J McCarthy and Sons, Wholesale Tea and Wine Merchants. Named the Clancarty (family of Carty) Buildings, the building was designed by architect and built by John Delaney. The Cork Examiner on 10 August 1896 (p.9) describes the impressive building: “No person passing through George’s street, can fail to see and admire the beautiful structure, which has just been completed. The facade is 54 feet long and 48 feet high, divided into four storeys, with round headed windows in the classic style, and extends more than the whole length of George’s Street, as between Cook street and Marlboro Street. The ground floor is divided by handsome wrought pilasters and consoles, each console decorated with floral swags, with a richly-moulded dental cornice immediately over the facia. This basement is perfectly fire proof, the walls being built of brick and cement, whilst the ceiling and floor over are composed of a solid block of concrete. The first, second and third floors immediately overhead are altogether occupied by the firm as warerooms to meet the requirements of their immense business as tea and wine merchants and whiskey shippers, the growth of which necessitates this great extension of their premises”.

47cm x 37cm Limerick The building itself it is a terraced eight-bay four-storey late-Victorian commercial building, It was built across 1895 and 1896 for J McCarthy and Sons, Wholesale Tea and Wine Merchants. Named the Clancarty (family of Carty) Buildings, the building was designed by architect and built by John Delaney. The Cork Examiner on 10 August 1896 (p.9) describes the impressive building: “No person passing through George’s street, can fail to see and admire the beautiful structure, which has just been completed. The facade is 54 feet long and 48 feet high, divided into four storeys, with round headed windows in the classic style, and extends more than the whole length of George’s Street, as between Cook street and Marlboro Street. The ground floor is divided by handsome wrought pilasters and consoles, each console decorated with floral swags, with a richly-moulded dental cornice immediately over the facia. This basement is perfectly fire proof, the walls being built of brick and cement, whilst the ceiling and floor over are composed of a solid block of concrete. The first, second and third floors immediately overhead are altogether occupied by the firm as warerooms to meet the requirements of their immense business as tea and wine merchants and whiskey shippers, the growth of which necessitates this great extension of their premises”.

J McCarthy and Sons, Wholesale Tea and Wine Merchants as shown in Goads Insurance Map of Cork, 1906 (source: Kieran McCarthy)

Description of Clancarty Buildings, Cork Examiner, 10 August 1896, p.9 (source: Cork City Library) -

47cm x 37cm Limerick The building itself it is a terraced eight-bay four-storey late-Victorian commercial building, It was built across 1895 and 1896 for J McCarthy and Sons, Wholesale Tea and Wine Merchants. Named the Clancarty (family of Carty) Buildings, the building was designed by architect and built by John Delaney. The Cork Examiner on 10 August 1896 (p.9) describes the impressive building: “No person passing through George’s street, can fail to see and admire the beautiful structure, which has just been completed. The facade is 54 feet long and 48 feet high, divided into four storeys, with round headed windows in the classic style, and extends more than the whole length of George’s Street, as between Cook street and Marlboro Street. The ground floor is divided by handsome wrought pilasters and consoles, each console decorated with floral swags, with a richly-moulded dental cornice immediately over the facia. This basement is perfectly fire proof, the walls being built of brick and cement, whilst the ceiling and floor over are composed of a solid block of concrete. The first, second and third floors immediately overhead are altogether occupied by the firm as warerooms to meet the requirements of their immense business as tea and wine merchants and whiskey shippers, the growth of which necessitates this great extension of their premises”.

47cm x 37cm Limerick The building itself it is a terraced eight-bay four-storey late-Victorian commercial building, It was built across 1895 and 1896 for J McCarthy and Sons, Wholesale Tea and Wine Merchants. Named the Clancarty (family of Carty) Buildings, the building was designed by architect and built by John Delaney. The Cork Examiner on 10 August 1896 (p.9) describes the impressive building: “No person passing through George’s street, can fail to see and admire the beautiful structure, which has just been completed. The facade is 54 feet long and 48 feet high, divided into four storeys, with round headed windows in the classic style, and extends more than the whole length of George’s Street, as between Cook street and Marlboro Street. The ground floor is divided by handsome wrought pilasters and consoles, each console decorated with floral swags, with a richly-moulded dental cornice immediately over the facia. This basement is perfectly fire proof, the walls being built of brick and cement, whilst the ceiling and floor over are composed of a solid block of concrete. The first, second and third floors immediately overhead are altogether occupied by the firm as warerooms to meet the requirements of their immense business as tea and wine merchants and whiskey shippers, the growth of which necessitates this great extension of their premises”.

J McCarthy and Sons, Wholesale Tea and Wine Merchants as shown in Goads Insurance Map of Cork, 1906 (source: Kieran McCarthy)

Description of Clancarty Buildings, Cork Examiner, 10 August 1896, p.9 (source: Cork City Library) -

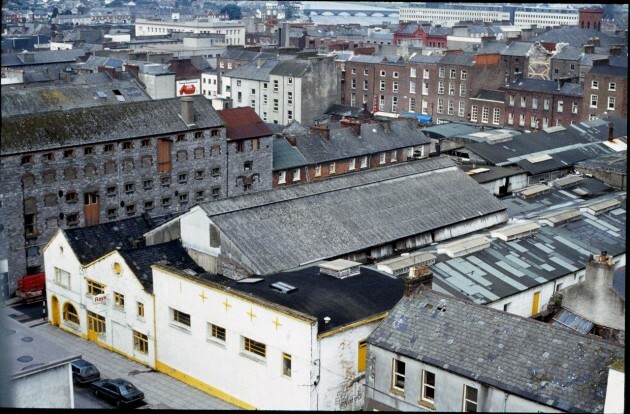

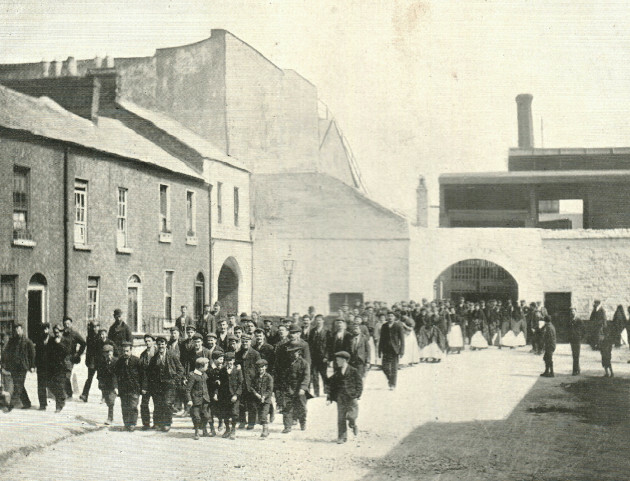

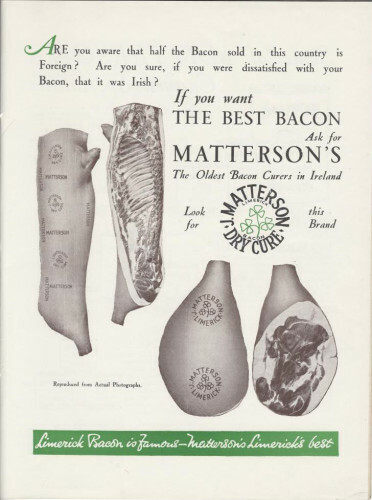

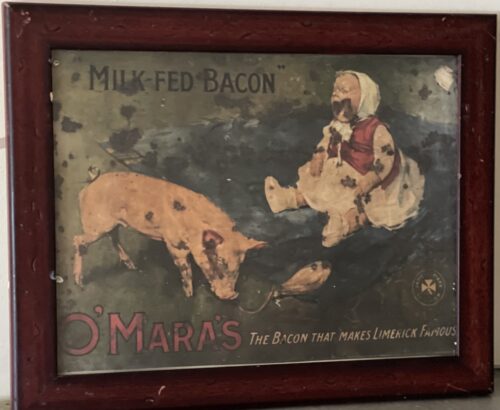

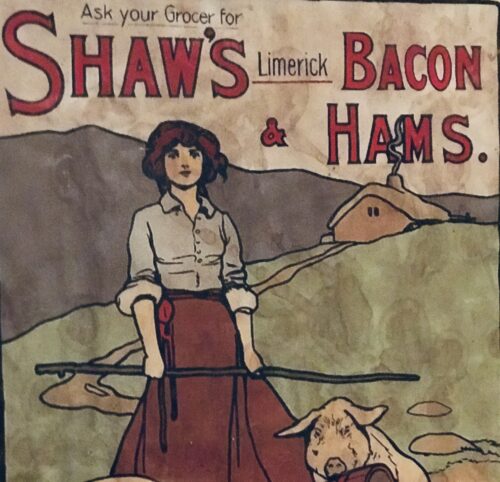

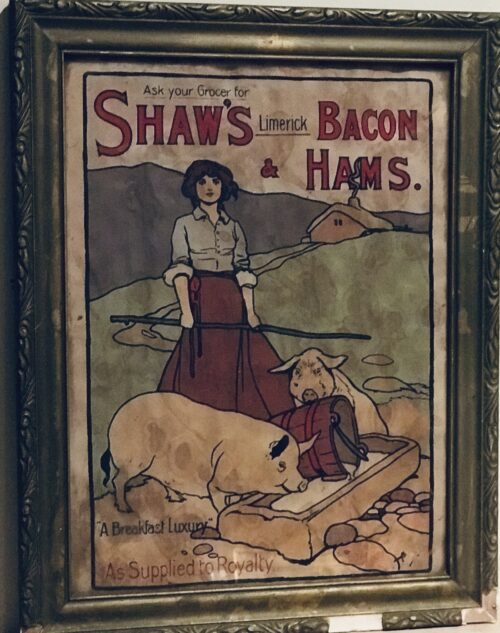

47cm x 37cm LimerickMuch of the last century, and indeed for well over half of the present one, Limerick's importance was directly attributed to her three well-known bacon factories, namely, J. Matterson & Sons, Roches Street, established in 1816 by Mr. John Russell, a Cumberland man in con-junction with Mr. Matterson, using the method of curing then current in Berwick-on-Tweed. W.J. Shaw & Sons, founded in the year 1831 at Mulgrave Street by William John Shaw, a descendant of a County Down family, and O'Mara's bacon factory, Roches Street, which had its origin in Mungret Street some few years before 1839, when James O'Mara from Toomevara started curing bacon in the basement of his house there. Apparently, this basement business flourished, for in 1839 he moved to Roches Street to the premises it last occupied .About the middle of the last century, for some reason now difficult to fathom, Limerick bacon and especially Limerick hams, became well-known for their excellent flavour throughout the English-speaking world. It is on record that Glasgow curers in an effort to produce hams equal in excellence to those of Limerick, imported Limerick workmen who were supposed to know all about the way in which the meat was turned out at home. Apparently, they did not bring secrets with them for their efforts were unsuccessful. There were also much larger bacon factories in parts of the British Isles; for instance, Belfast is reputed to have exported four times the number of hams produced in Limerick, and places like Glasgow and Liverpool had several factories producing very large quantities of bacon as well. None of them, however, quite matched' those produced in the three local factories for flavour and quality.O’MARA’S, MATTERSON’S, SHAW’S and Denny’s were the names that made Limerick famous for its bacon produce for 180 years – earning it the nickname ‘Pigstown’. The reputation of Limerick ham, the food culture that arose from a plentiful supply of cheap products, the story of the pork butchers, the pig buyers, the sounds of the city with factory horns signalling the call to work – all of these still resonate in Limerick in the memories of its citizens and former workers. A definitive account of this industry that operated at the centre of the city, supplied by the farms of rural county Limerick for over 180 years will be documented in a new book called Pigtown – A History of Limerick’s Bacon Industry. Ruth Guiry was commissioned to undertake the research under the guidance of Dr Maura Cronin from Mary Immaculate College and one of the 27 people she interviewed to understand the role the bacon factories had in Limerick was Joe Hayes. Joe Hayes started working in a bacon factory in 1962, aged 16 years old. He worked with his dad, and later on with his two sons until the factory closed in 1986. “When the factory closed, a group of us got our own little unit, we rented it, and produced our own sausages, puddings and things.” It was a huge part of Limerick’s social scene: four generations of Joe’s family worked in bacon factories, with uncles, sisters, brothers, sons and cousins all working in the factory at one time or another: “If one factory was caic, you wouldn’t have a problem getting a job in the other one. And he doesn’t mince his word when talking about the work they did. “They brought the pigs in, we killed the pigs, and prepared the bacon: that’s the way it was in the bacon factories.” When asked about if there were ever animal cruelty protests, he laughs at the idea.

47cm x 37cm LimerickMuch of the last century, and indeed for well over half of the present one, Limerick's importance was directly attributed to her three well-known bacon factories, namely, J. Matterson & Sons, Roches Street, established in 1816 by Mr. John Russell, a Cumberland man in con-junction with Mr. Matterson, using the method of curing then current in Berwick-on-Tweed. W.J. Shaw & Sons, founded in the year 1831 at Mulgrave Street by William John Shaw, a descendant of a County Down family, and O'Mara's bacon factory, Roches Street, which had its origin in Mungret Street some few years before 1839, when James O'Mara from Toomevara started curing bacon in the basement of his house there. Apparently, this basement business flourished, for in 1839 he moved to Roches Street to the premises it last occupied .About the middle of the last century, for some reason now difficult to fathom, Limerick bacon and especially Limerick hams, became well-known for their excellent flavour throughout the English-speaking world. It is on record that Glasgow curers in an effort to produce hams equal in excellence to those of Limerick, imported Limerick workmen who were supposed to know all about the way in which the meat was turned out at home. Apparently, they did not bring secrets with them for their efforts were unsuccessful. There were also much larger bacon factories in parts of the British Isles; for instance, Belfast is reputed to have exported four times the number of hams produced in Limerick, and places like Glasgow and Liverpool had several factories producing very large quantities of bacon as well. None of them, however, quite matched' those produced in the three local factories for flavour and quality.O’MARA’S, MATTERSON’S, SHAW’S and Denny’s were the names that made Limerick famous for its bacon produce for 180 years – earning it the nickname ‘Pigstown’. The reputation of Limerick ham, the food culture that arose from a plentiful supply of cheap products, the story of the pork butchers, the pig buyers, the sounds of the city with factory horns signalling the call to work – all of these still resonate in Limerick in the memories of its citizens and former workers. A definitive account of this industry that operated at the centre of the city, supplied by the farms of rural county Limerick for over 180 years will be documented in a new book called Pigtown – A History of Limerick’s Bacon Industry. Ruth Guiry was commissioned to undertake the research under the guidance of Dr Maura Cronin from Mary Immaculate College and one of the 27 people she interviewed to understand the role the bacon factories had in Limerick was Joe Hayes. Joe Hayes started working in a bacon factory in 1962, aged 16 years old. He worked with his dad, and later on with his two sons until the factory closed in 1986. “When the factory closed, a group of us got our own little unit, we rented it, and produced our own sausages, puddings and things.” It was a huge part of Limerick’s social scene: four generations of Joe’s family worked in bacon factories, with uncles, sisters, brothers, sons and cousins all working in the factory at one time or another: “If one factory was caic, you wouldn’t have a problem getting a job in the other one. And he doesn’t mince his word when talking about the work they did. “They brought the pigs in, we killed the pigs, and prepared the bacon: that’s the way it was in the bacon factories.” When asked about if there were ever animal cruelty protests, he laughs at the idea.

They started at 8am and finished at 5.30 working a 40 hour week when the factory closed in 1986, but despite their work, the people who worked in factories often couldn’t afford to buy the expensive cuts of meat. After the expensive cuts were prepared, the offal, the spare ribs, the pigs’ heads would go to the poorer people. “The blood was used to make the pudding, the packet, the tripe was made off the belly. Everything was used off the pig, and it fed Limerick city.” It was a way of life down in Limerick, so when the factories closed, thousands of people working in a bacon factories were out of jobs, and thousands of families were affected. But it wasn’t the competition from big supermarkets that did it – it was free trade. The Danes, the French, the Dutch all started exporting their products here, and Limerick factories didn’t have the money to export to compete. “Michael O’Mara’s funeral was this week – he was the last of the bacon factory managers.” says Joe. “After the Limerick factory closed, he tried doing different bits and pieces, but nothing worked out for him, so he worked in a factory for a couple of years before retiring.” Joe Hayes himself is retired now, and when he buys his meat he gets it in a supermarket. “Meat is meat,” he says.”But if I see the tricolour flag, I’ll still buy it even if it’s dearer.” Pigtown - A History of Limerick’s Bacon Industry by Ruth Guiry is co-edited by Dr Maura Cronin and Jacqui Hayes.People still eat sausages and bacon – where do they think they come from? -

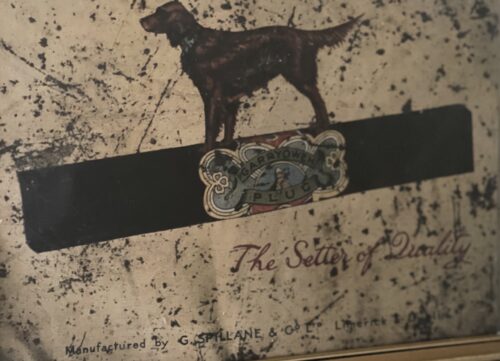

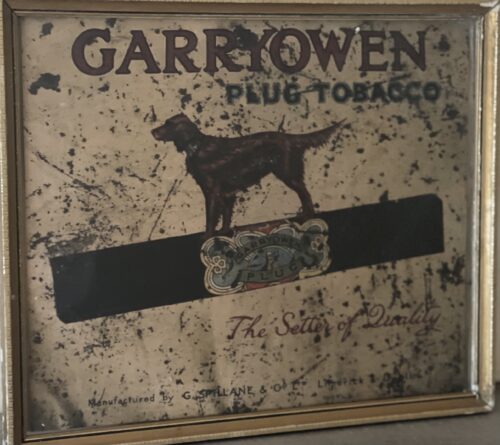

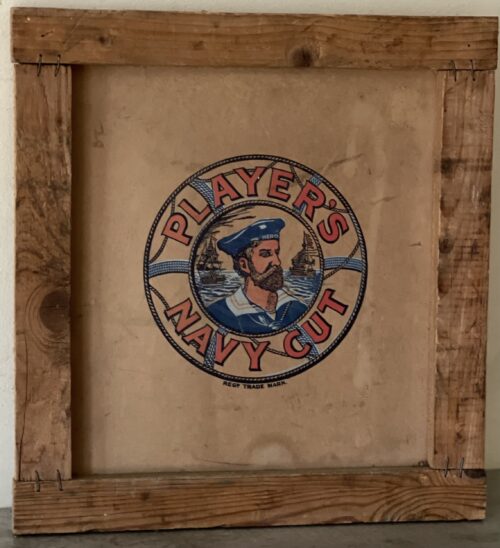

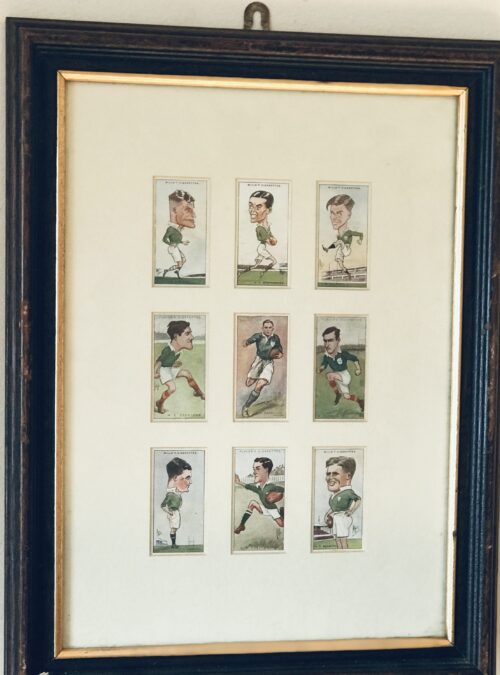

40cm x 34cm Limerick In 1929, Limerick city was the home to two large of tobacco factories Spillane’s and Clune’s who imported tobacco from the United States, Egypt and Turkey as well as locally grown tobacco to produce their famed products. Spillane’s Tobacco Factory on Sarsfield Street was started by John Spillane in 1829 and was known as ‘The House of Garryowen’. A hundred years later they were employing a hundred people. The famous Garryowen plug formed 80 per cent of the factories output while they had other products including Popular and Treaty bar plugs, Hazel Nut plug, Special Flake, Handy Cut Flake, snuffs, Cashel, High Toast, White Top and Craven A cigarettes. To meet a special demand from the North of Ireland the factory produced a type of plug known as Long Square. Spillane’s closed in 1958 with the loss of 150 jobs after the building was purchased by Murray Ltd, of Dublin the year previous. Their building is where the old Dunnes Stores building stands today. William Spillane who was the Mayor of Limerick in 1885 built the Spillane Tower which today is better known as the ‘Snuff Box’ on the banks of the Shannon river at Corkanree. The other large factory was Clune’s Tobacco Factory on Denmark Street. It opened in the late 1872 and had about 60 employees in 1929. The firm specialised in Big Bar Plug, every two ounces of which is stamped Thomond. They also excelled in the Far-Famed Limerick Twist. They were also known for Kincora Plug, Sarsfield Plug, Home Rule, Hibernian, Target, Ireland’s Pride and Two Flake. A popular item associated with tobacco factories are the cigarette cards. Cigarette cards were originally produced as a small piece of card which was designed to protect the individual cigarettes from being squashed as the original packaging was paper and not the card boxes that we know today. We must not forget M.Cahill’s of Wickham Street which housed a snuff factory in 1870 in the basement of the building and operated for over sixty years. The business was founded by Michael Cahill (c.1846-1918) who was also the director of the Limerick Race Company. Cahill’s became Ireland’s longest running tobacco store and is still in operation offering a selection of cigar, teas and “gentleman’s gifts” including Swiss army knives, hipflasks and pipes.

40cm x 34cm Limerick In 1929, Limerick city was the home to two large of tobacco factories Spillane’s and Clune’s who imported tobacco from the United States, Egypt and Turkey as well as locally grown tobacco to produce their famed products. Spillane’s Tobacco Factory on Sarsfield Street was started by John Spillane in 1829 and was known as ‘The House of Garryowen’. A hundred years later they were employing a hundred people. The famous Garryowen plug formed 80 per cent of the factories output while they had other products including Popular and Treaty bar plugs, Hazel Nut plug, Special Flake, Handy Cut Flake, snuffs, Cashel, High Toast, White Top and Craven A cigarettes. To meet a special demand from the North of Ireland the factory produced a type of plug known as Long Square. Spillane’s closed in 1958 with the loss of 150 jobs after the building was purchased by Murray Ltd, of Dublin the year previous. Their building is where the old Dunnes Stores building stands today. William Spillane who was the Mayor of Limerick in 1885 built the Spillane Tower which today is better known as the ‘Snuff Box’ on the banks of the Shannon river at Corkanree. The other large factory was Clune’s Tobacco Factory on Denmark Street. It opened in the late 1872 and had about 60 employees in 1929. The firm specialised in Big Bar Plug, every two ounces of which is stamped Thomond. They also excelled in the Far-Famed Limerick Twist. They were also known for Kincora Plug, Sarsfield Plug, Home Rule, Hibernian, Target, Ireland’s Pride and Two Flake. A popular item associated with tobacco factories are the cigarette cards. Cigarette cards were originally produced as a small piece of card which was designed to protect the individual cigarettes from being squashed as the original packaging was paper and not the card boxes that we know today. We must not forget M.Cahill’s of Wickham Street which housed a snuff factory in 1870 in the basement of the building and operated for over sixty years. The business was founded by Michael Cahill (c.1846-1918) who was also the director of the Limerick Race Company. Cahill’s became Ireland’s longest running tobacco store and is still in operation offering a selection of cigar, teas and “gentleman’s gifts” including Swiss army knives, hipflasks and pipes. -

50cm x 40cm Limerick John Jameson was originally a lawyer from Alloa in Scotland before he founded his eponymous distillery in Dublin in 1780.Prevoius to this he had made the wise move of marrying Margaret Haig (1753–1815) in 1768,one of the simple reasons being Margaret was the eldest daughter of John Haig, the famous whisky distiller in Scotland. John and Margaret had eight sons and eight daughters, a family of 16 children. Portraits of the couple by Sir Henry Raeburn are on display in the National Gallery of Ireland. John Jameson joined the Convivial Lodge No. 202, of the Dublin Freemasons on the 24th June 1774 and in 1780, Irish whiskey distillation began at Bow Street. In 1805, he was joined by his son John Jameson II who took over the family business that year and for the next 41 years, John Jameson II built up the business before handing over to his son John Jameson the 3rd in 1851. In 1901, the Company was formally incorporated as John Jameson and Son Ltd. Four of John Jameson’s sons followed his footsteps in distilling in Ireland, John Jameson II (1773 – 1851) at Bow Street, William and James Jameson at Marrowbone Lane in Dublin (where they partnered their Stein relations, calling their business Jameson and Stein, before settling on William Jameson & Co.). The fourth of Jameson's sons, Andrew, who had a small distillery at Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, was the grandfather of Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of wireless telegraphy. Marconi’s mother was Annie Jameson, Andrew’s daughter. John Jameson’s eldest son, Robert took over his father’s legal business in Alloa. The Jamesons became the most important distilling family in Ireland, despite rivalry between the Bow Street and Marrowbone Lane distilleries. By the turn of the 19th century, it was the second largest producer in Ireland and one of the largest in the world, producing 1,000,000 gallons annually. Dublin at the time was the centre of world whiskey production. It was the second most popular spirit in the world after rum and internationally Jameson had by 1805 become the world's number one whiskey. Today, Jameson is the world's third largest single-distillery whiskey. Historical events, for a time, set the company back. The temperance movement in Ireland had an enormous impact domestically but the two key events that affected Jameson were the Irish War of Independence and subsequent trade war with the British which denied Jameson the export markets of the Commonwealth, and shortly thereafter, the introduction of prohibition in the United States. While Scottish brands could easily slip across the Canada–US border, Jameson was excluded from its biggest market for many years. The introduction of column stills by the Scottish blenders in the mid-19th-century enabled increased production that the Irish, still making labour-intensive single pot still whiskey, could not compete with. There was a legal enquiry somewhere in 1908 to deal with the trade definition of whiskey. The Scottish producers won within some jurisdictions, and blends became recognised in the law of that jurisdiction as whiskey. The Irish in general, and Jameson in particular, continued with the traditional pot still production process for many years.In 1966 John Jameson merged with Cork Distillers and John Powers to form the Irish Distillers Group. In 1976, the Dublin whiskey distilleries of Jameson in Bow Street and in John's Lane were closed following the opening of a New Midleton Distillery by Irish Distillers outside Cork. The Midleton Distillery now produces much of the Irish whiskey sold in Ireland under the Jameson, Midleton, Powers, Redbreast, Spot and Paddy labels. The new facility adjoins the Old Midleton Distillery, the original home of the Paddy label, which is now home to the Jameson Experience Visitor Centre and the Irish Whiskey Academy. The Jameson brand was acquired by the French drinks conglomerate Pernod Ricard in 1988, when it bought Irish Distillers. The old Jameson Distillery in Bow Street near Smithfield in Dublin now serves as a museum which offers tours and tastings. The distillery, which is historical in nature and no longer produces whiskey on site, went through a $12.6 million renovation that was concluded in March 2016, and is now a focal part of Ireland's strategy to raise the number of whiskey tourists, which stood at 600,000 in 2017.Bow Street also now has a fully functioning Maturation Warehouse within its walls since the 2016 renovation. It is here that Jameson 18 Bow Street is finished before being bottled at Cask Strength. In 2008, The Local, an Irish pub in Minneapolis, sold 671 cases of Jameson (22 bottles a day),making it the largest server of Jameson's in the world – a title it maintained for four consecutive years.

50cm x 40cm Limerick John Jameson was originally a lawyer from Alloa in Scotland before he founded his eponymous distillery in Dublin in 1780.Prevoius to this he had made the wise move of marrying Margaret Haig (1753–1815) in 1768,one of the simple reasons being Margaret was the eldest daughter of John Haig, the famous whisky distiller in Scotland. John and Margaret had eight sons and eight daughters, a family of 16 children. Portraits of the couple by Sir Henry Raeburn are on display in the National Gallery of Ireland. John Jameson joined the Convivial Lodge No. 202, of the Dublin Freemasons on the 24th June 1774 and in 1780, Irish whiskey distillation began at Bow Street. In 1805, he was joined by his son John Jameson II who took over the family business that year and for the next 41 years, John Jameson II built up the business before handing over to his son John Jameson the 3rd in 1851. In 1901, the Company was formally incorporated as John Jameson and Son Ltd. Four of John Jameson’s sons followed his footsteps in distilling in Ireland, John Jameson II (1773 – 1851) at Bow Street, William and James Jameson at Marrowbone Lane in Dublin (where they partnered their Stein relations, calling their business Jameson and Stein, before settling on William Jameson & Co.). The fourth of Jameson's sons, Andrew, who had a small distillery at Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, was the grandfather of Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of wireless telegraphy. Marconi’s mother was Annie Jameson, Andrew’s daughter. John Jameson’s eldest son, Robert took over his father’s legal business in Alloa. The Jamesons became the most important distilling family in Ireland, despite rivalry between the Bow Street and Marrowbone Lane distilleries. By the turn of the 19th century, it was the second largest producer in Ireland and one of the largest in the world, producing 1,000,000 gallons annually. Dublin at the time was the centre of world whiskey production. It was the second most popular spirit in the world after rum and internationally Jameson had by 1805 become the world's number one whiskey. Today, Jameson is the world's third largest single-distillery whiskey. Historical events, for a time, set the company back. The temperance movement in Ireland had an enormous impact domestically but the two key events that affected Jameson were the Irish War of Independence and subsequent trade war with the British which denied Jameson the export markets of the Commonwealth, and shortly thereafter, the introduction of prohibition in the United States. While Scottish brands could easily slip across the Canada–US border, Jameson was excluded from its biggest market for many years. The introduction of column stills by the Scottish blenders in the mid-19th-century enabled increased production that the Irish, still making labour-intensive single pot still whiskey, could not compete with. There was a legal enquiry somewhere in 1908 to deal with the trade definition of whiskey. The Scottish producers won within some jurisdictions, and blends became recognised in the law of that jurisdiction as whiskey. The Irish in general, and Jameson in particular, continued with the traditional pot still production process for many years.In 1966 John Jameson merged with Cork Distillers and John Powers to form the Irish Distillers Group. In 1976, the Dublin whiskey distilleries of Jameson in Bow Street and in John's Lane were closed following the opening of a New Midleton Distillery by Irish Distillers outside Cork. The Midleton Distillery now produces much of the Irish whiskey sold in Ireland under the Jameson, Midleton, Powers, Redbreast, Spot and Paddy labels. The new facility adjoins the Old Midleton Distillery, the original home of the Paddy label, which is now home to the Jameson Experience Visitor Centre and the Irish Whiskey Academy. The Jameson brand was acquired by the French drinks conglomerate Pernod Ricard in 1988, when it bought Irish Distillers. The old Jameson Distillery in Bow Street near Smithfield in Dublin now serves as a museum which offers tours and tastings. The distillery, which is historical in nature and no longer produces whiskey on site, went through a $12.6 million renovation that was concluded in March 2016, and is now a focal part of Ireland's strategy to raise the number of whiskey tourists, which stood at 600,000 in 2017.Bow Street also now has a fully functioning Maturation Warehouse within its walls since the 2016 renovation. It is here that Jameson 18 Bow Street is finished before being bottled at Cask Strength. In 2008, The Local, an Irish pub in Minneapolis, sold 671 cases of Jameson (22 bottles a day),making it the largest server of Jameson's in the world – a title it maintained for four consecutive years. -

40cm x 34cm Limerick Sullivan’s Brewing Company opened for business over three hundred years ago in The Maltings on James’s Street, smack bang in the middle of Kilkenny City.

40cm x 34cm Limerick Sullivan’s Brewing Company opened for business over three hundred years ago in The Maltings on James’s Street, smack bang in the middle of Kilkenny City.Up until the early 1700s, brewing on a large scale was a rarity, this resulted in many small breweries springing up all around the country, with little or no consistency in the beer that was being produced. Back then, to guarantee that each pint was as good as the last, required brewing on a bigger, more exacting scale.

Enter Mr. Sullivan, a man of high morals, integrity and a good nose for great beer. Through his belief and hard work he established a brewery the likes of which had never been seen in Kilkenny. He only used the very best local ingredients and the very best brewing methods to ensure that every barrel of Sullivan’s Red Ale that left his brewery was as good as the one that had gone before.

Richard Sullivan was elected to represent the people of Kilkenny in the 1820s. This supposedly put one well-known Irish political figure’s nose well and truly out of joint – Daniel O’Connell.After one particularly heated parliamentary quarrel, O’Connell even called a boycott of Sullivan’s Ale by the people of Kilkenny. But you’ll know if you’ve ever had a pint of Sullivan’s Red Ale in front of you that it can be very hard to resist, and the boycott was soon called off.

Despite this rocky start, Richard and Daniel went on to become firm friends. So good in fact, that when O’Connell was stripped of his seat in Parliament due to some underhand dealings, Sullivan was one of the few who had his back. He wrote to Daniel and offered him his seat to ensure that O’Connell’s Catholic Emancipation Act would get through Parliament.

1802MIXING BUSINESS AND POLITICSGOOD WILL, KINDNESS AND HOT SOUP

1880 was the year of ‘The Great Sullivan’s Brewery Fire’, a day that has gone down in legend among the people of Kilkenny.The story goes that the Sullivan Family took the day off brewing to attend the funeral of a recently departed family friend in a Kilkenny hilltop chapel. Leaving a funeral before all the formalities were completed was the height of bad manners. The Sullivans could see the brewery ablaze from the hillside, but could do nothing about it.

As the first flames began to lick the outside of the brewery, the alarm was raised and the local fire brigade was sent for. But The Kilkenny Fire Brigade consisted of a few volunteers, a horse and a cart and a useless, leaking hose. Due to all their good deeds over the years, the Sullivans were a tremendously popular family in Kilkenny, so men, women and children from far and wide rallied together and grabbed the nearest buckets, pales and pots, filling them with water and battling the fire. Within an hour the fire was under control and the brewery was saved, all because a community came together.

1880A COMMUNITY WORKING TOGETH1918

BLACK SHEEP AND THE LOST WAGER

After Sullivan’s Brewery closed for the final time in the early 1900s the tales of the good deeds of this Sullivan Family began to fade into memory.

Over the coming decades, the independent breweries that were once synonymous with Kilkenny began to drop off one by one, until its final working brewery sadly closed its doors in 2013. However, there wasn’t long to wait for a change of fortunes for Kilkenny-brewed ale, as 2016 saw two great families coming together to return traditional Irish brewing to its spiritual home.

The Smithwick Family in partnership with direct descendants of the Sullivan Family had a vision to re-open the once-great brewery in the city where it all began. They enlisted the help of Ian Hamilton, one of Ireland’s most eminent contemporary master-brewers. Together they are bringing artisan brewing back to Kilkenny.

If people thought that brewing in Kilkenny was dead and buried, they are in for a rude awakening…

2016

TWO GREAT FAMILIES AND THE RETURN OF SULLIVANS

WE’RE BACK AND HERE TO STAY

-

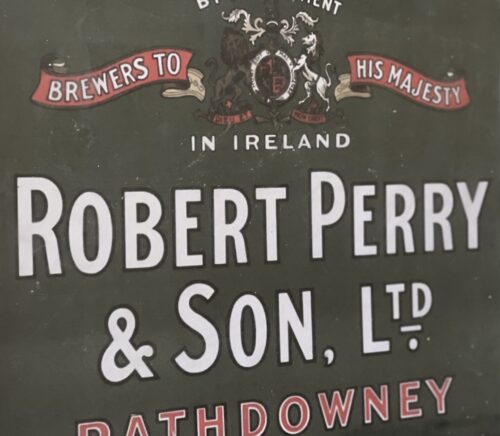

40cm x 34cm Limerickessrs Robert Perry & Son Limited were registered as a limited company in 1877, but the brewery dates back to 1800 when it was started by the Perry family. The brewery was located in Rathdowney, county Laois. In connection with the Brewery were extensive maltings, with branches at Donaghmore, Brosna and Roscrea, and only Irish barley was used. It is claimed that they were the first brewer to chill and filter ale in around 1900. A unique feature of the business is the brewing of non-deposit ale under sole rights for Ireland and the company has the distinction of holding a Royal warrant as brewers to Queen Victoria. From 1950 their trade deteriorated and losses were incurred. The Dixon family (Green's of Luton and subsequently Flowers) had a controlling interest. In 1956 Captain T.R. Dixon acquired the entire share capital of the company. In the same year, they were receiving assistance from Flowers in the form of a second hand plant to produce chilled and filtered beers. In June 1957 Cherry's Breweries Limited bought out a quantity of ordinary and preference stock. In August 1959 Cherry's made a successful offer for the outstanding stock, and Perry's became a wholly owned subsidiary of Cherry's Breweries Limited. In 1965 they were owned by Cherry's Breweries Limited (held by AGS(D) and IAB). The directors were D.O. Williams (Assistant Managing Director of AGS(D)), A.C. Parker and J.D. Hudson. The secretary was N.J. McCullough (he also held the position of accountant), the brewer W.St.J. Mitchell. They employed 5 male office staff, 37 male employees in the brewery and maltings and 8 drivers. The products included: Perry's India Pale Ale, Perry's Pale Ale, Perry's XX Ale, Perry's X Ale. There were no trademarks held.

40cm x 34cm Limerickessrs Robert Perry & Son Limited were registered as a limited company in 1877, but the brewery dates back to 1800 when it was started by the Perry family. The brewery was located in Rathdowney, county Laois. In connection with the Brewery were extensive maltings, with branches at Donaghmore, Brosna and Roscrea, and only Irish barley was used. It is claimed that they were the first brewer to chill and filter ale in around 1900. A unique feature of the business is the brewing of non-deposit ale under sole rights for Ireland and the company has the distinction of holding a Royal warrant as brewers to Queen Victoria. From 1950 their trade deteriorated and losses were incurred. The Dixon family (Green's of Luton and subsequently Flowers) had a controlling interest. In 1956 Captain T.R. Dixon acquired the entire share capital of the company. In the same year, they were receiving assistance from Flowers in the form of a second hand plant to produce chilled and filtered beers. In June 1957 Cherry's Breweries Limited bought out a quantity of ordinary and preference stock. In August 1959 Cherry's made a successful offer for the outstanding stock, and Perry's became a wholly owned subsidiary of Cherry's Breweries Limited. In 1965 they were owned by Cherry's Breweries Limited (held by AGS(D) and IAB). The directors were D.O. Williams (Assistant Managing Director of AGS(D)), A.C. Parker and J.D. Hudson. The secretary was N.J. McCullough (he also held the position of accountant), the brewer W.St.J. Mitchell. They employed 5 male office staff, 37 male employees in the brewery and maltings and 8 drivers. The products included: Perry's India Pale Ale, Perry's Pale Ale, Perry's XX Ale, Perry's X Ale. There were no trademarks held. -

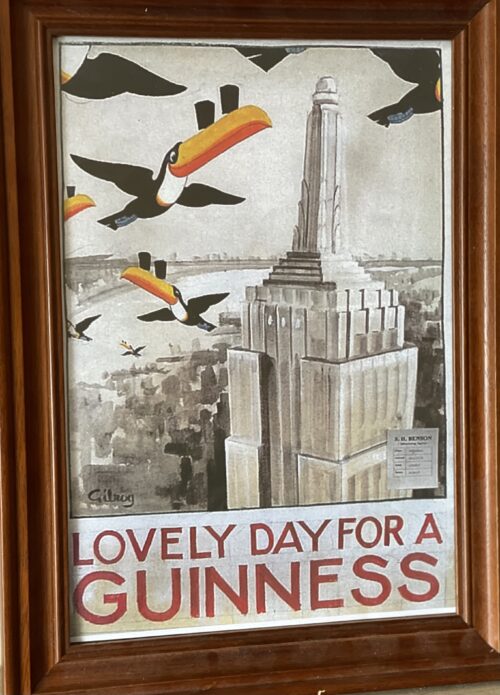

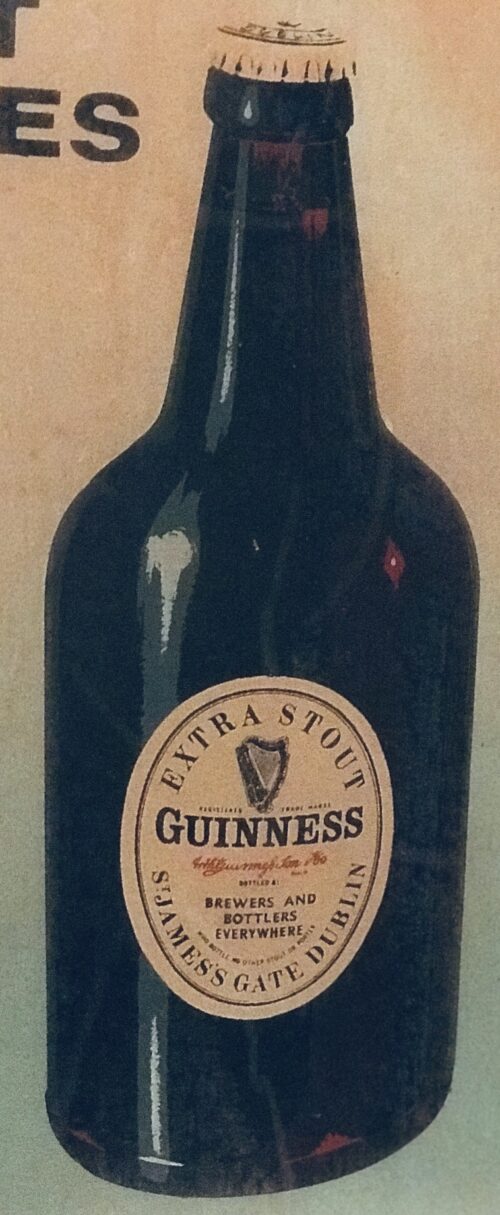

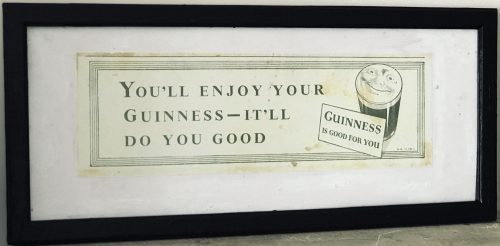

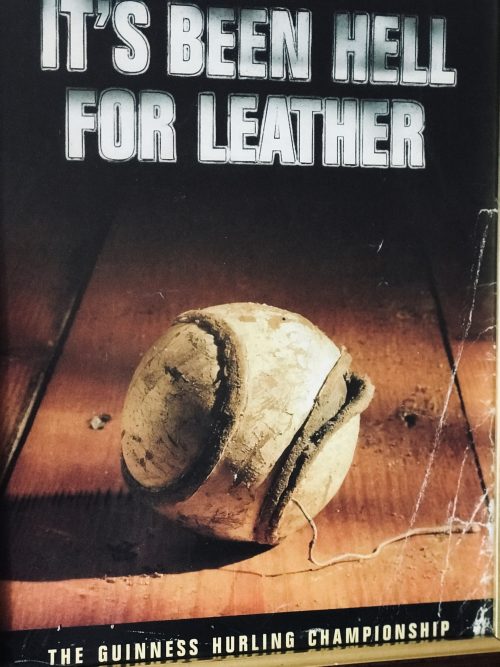

Vintage type come in for a Guinness advert with suitably distressed appearance. Dimensions : 23cm x 40cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm