Events

"Footballers are pragmatists. You play for the manager you have."

This is a quote from Roy Keane's autobiography [Page 76]. He was referring specifically to the Irish soccer players when Jack Charlton was the Republic of Ireland team manager, and to footballers in general. It would appear however that Keane had limits to his own pragmatism when it came to playing for Mick McCarthy as Irish manager.

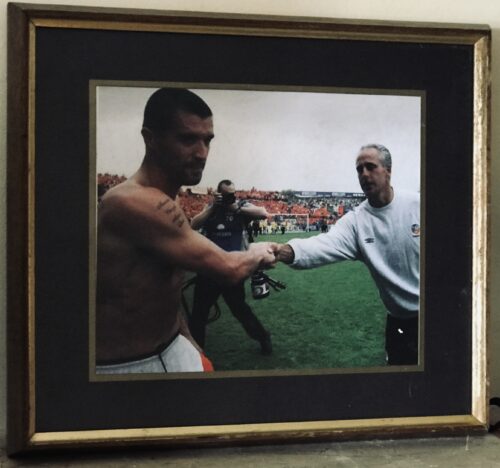

The dynamics of the relationship between Roy Keane and Mick McCarthy are central to the whole Saipan incident. Clearly the two did not get on with each other. The question is - why? Keane and McCarthy are the only ones who can give a definitive answer to this but based upon the available evidence it appears to be primarily due to an intense dislike of McCarthy by Keane.

Roy Keane and Mick McCarthy only played together for Ireland on two occasions, in September 1991 and May 1992. There are no generally known reports of any issues arising between the two men as players on the football pitch. However it was while Mick McCarthy was the Republic of Ireland team captain that the first instance of some discord between the two has been documented. During the fateful squad meeting, that led to the expulsion of Keane from the Irish World Cup squad, the Irish captain brought up an incident that had occurred a full ten years earlier. The now infamous Boston 1992 row.

It now seems that this otherwise innocuous event appears to have coloured the Keane and McCarthy relationship

from that time onward. A drunken 20 year old Keane had turned up late for the team bus at the end of a soccer tournament in the US. When the team captain Mick McCarthy challenged Keane about being late a heated row ensued. Roy Keane seems to have taken extreme exception to this. It is difficult to believe that such an event would even register the next day with Keane who seems to have spent his entire life going from one scrape to another. Keane admits in his autobiography that he has had hundreds or thousands of rows throughout his soccer career. Why should this one have been so significant to him?One possible explanation is that when Keane is drunk his, already low, tolerance levels become even lower. Any perceived slight is magnified disproportionately. Keane's autobiography is littered with stories about him getting into angry and violent situations when he was drunk. By his own admission there were many situations when he knew he should have walked away but his own sense of offence prevented him doing just that. These events seem to have made an indelible mark on his brain as they are recounted with real clarity in his book. It seems that a run of the mill, for footballers, exchange between McCarthy and Keane in 1992, magnified in intensity by his drunken state, soured Keane's view of McCarthy from that point on.

There do not appear to have been any further meaningful interactions between the two until McCarthy was appointed as manager of the Republic of Ireland football team in 1996. In his autobiography [Page 246] Keane reveals an antipathy towards McCarthy that seems, to some extent, to be born out of Roy Keane's relationship with Jack Charlton. In his book Keane makes it clear that he had no time for Charlton "...I found it impossible to relate to him as a man or as a coach." [Page 54]. When commenting on McCarthy's appointment as Irish manager he said "McCarthy was part of the Charlton legend. Captain Fantastic...he didn't convince me. Still, when he got the job, I thought: let bygones be bygones." What bygones? Presumably the exchange between the pair in Boston six years earlier?

In his World Cup Diary McCarthy makes a case that he had gone to some lengths as manager of Ireland to accommodate Keane and his sensitivities. He had made Keane the captain of Ireland at the first opportunity. He allowed Keane to turn up later than the other players for international matches. Keane was the only player in the Irish squad that roomed alone. He also says that he put up "...with the odd tantrum from Keane here and there...". McCarthy contends that if he was holding a grudge towards Keane from 1992 he would not have gone to these lengths.

Roy Keane's first match for Ireland with Mick McCarthy as manager was an inauspicious occasion for the Manchester United player. Earning his 30th cap and wearing the captain's armband in place of the substituted Andy Townsend, Keane was sent off late in the match for kicking a Russian player.

The next notable point of conflict between Keane and McCarthy was on the occasion of a Republic of Ireland trip to the USA for an end of season international tournament in 1996. Keane decided that he didn't want to go as he was too tired after the season just ended. [Page 246]. Rather than contact McCarthy or anyone else in the Irish set up, Keane left it to someone at Old Trafford to inform the FAI. "As a result I got off to a bad start with McCarthy. He felt I should have spoken to him personally. He expressed this opinion, casting me in a bad light. What he didn't tell the media that if we had that sort of conversation on this occasion, it would have been our first." [Page 247]. This begs the question, why couldn't Keane contact McCarthy directly? Why would this have been the first such discussion between the two men as manager and team captain? It certainly doesn't suggest that Keane had, in reality, let bygones be bygones.

In his World Cup Diary McCarthy refers to the the 1996 USA trip. "I was never that bothered if he (Keane) went to America or not...it became a big media story...We have had a few chats to sort things out but it has all dragged on since then in the press." [Page 33].

In his autobiography Keane complains bitterly about the poor Republic of Ireland set up especially when compared to that of Manchester United. After the draw for the 2002 World Cup qualifiers was made Keane says that he met with McCarthy"...to level with him, to make the case for a reformed approach...We discussed the problems. He agreed with me...It was not and easy conversation - we're not not buddy-buddy...I thought we had a deal."[Page 250]. Interestingly this meeting took place at Keane's house in Manchester.

What is clear is that there was an unusual relationship between the Irish manager and his captain. Direct communication between McCarthy and Keane was kept to an absolute minimum. All of the available evidence is that was the way Keane wanted it. Keane admitted this in his interview with Tom Humphries in Saipan "I spoke to Mick Byrne, who's the middle man for me, really." For a man who has very admirable communication skills this is somewhat strange. Why would he need a middle man? The only possible explanation is that Roy Keane did not like Mick McCarthy and couldn't bear to be anywhere near him or have anything to do with him. During McCarthy's tenure as Irish manager Roy Keane took every opportunity to minimise his time with the Irish squad. "I dreaded the prospect of international weeks."[Page 250].

With the benefit of hindsight and with the insights afforded by Keane's autobiography it is clear that there was no way possible that Roy Keane could maintain an even keel while being away with Ireland for the duration of the World Cup campaign. All of his complaints about the crowded airport, the missing training gear, the poor training facilities, the goalkeeper row, were just symptoms. Clearly McCarthy and the FAI could have done better but the inescapable conclusion to be drawn is that even if conditions and facilities had been perfect Keane simply could not endure being in such close proximity to Mick McCarthy for such a protracted period of time. A Saipan incidentwas inevitable even before Roy Keane set foot on the plane to that Pacific island.

NOTE: Unless stated otherwise all quotations are from: Keane: The Autobiography; Roy Keane with Eamon Dunphy (2002); Michael Joseph Ltd

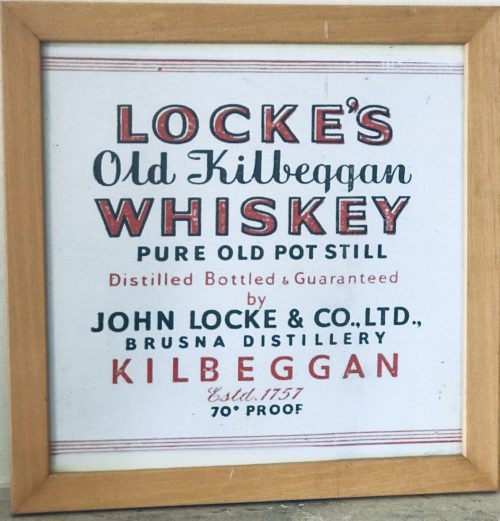

An Address from the People of Kilbeggan to John Locke, Esq. Dear Sir - Permit us, your fellow townsmen, to assure of our deep and cordial sympathy in your loss and disappointment from the accident which occurred recently in your Distillery. Sincerely as we regret the accident, happily unattended with loss of life, we cannot but rejoice at the long-wished-for opportunity it affords us of testifying to you the high appreciation in which we hold you for your public and private worth. We are well aware that the restrictions imposed by recent legislation on that particular branch of Irish industry, with which you have been so long identified, have been attended with disastrous results to the trade, as is manifest in the long list of Distilleries now almost in ruins, and which were a few years ago centres of busy industry, affording remunerative employment to thousands of hands; and we are convinced the Kilbeggan Distillery would have long since swelled the dismal catalogue had it fallen into less energetic and enterprising hands. In such an event we would be compelled to witness the disheartening scene of a large number of our working population without employment during that period of the year when employment Is scarcest, and at the same time most essential to the poor. Independent then of what we owe you, on purely personal grounds, we feel we owe you a deep debt of gratitude for maintaining in our midst a manufacture which affords such extensive employment to our poor, and exercises so favourable an influence on the prosperity of the town. In conclusion, dear Sir, we beg your acceptance of a new steam boiler to replace the injured one, as testimony, inadequate though it is, of our unfeigned respect and esteems for you ; and we beg to present it with the ardent wish and earnest hope that, for many long years to come, it may contribute to enhance still more the deservedly high and increasing reputation of the Kilbeggan Distillery.In a public response to mark the gift, also published in several newspapers, Locke thanked the people of Kilbeggan for their generosity, stating "...I feel this to be the proudest day of my life...". A plaque commemorating the event hangs in the distillery's restaurant today. In 1878, a fire broke out in the "can dip" (sampling) room of the distillery, and spread rapidly. Although, the fire was extinguished within an hour, it destroying a considerable portion of the front of the distillery and caused £400 worth of damage. Hundreds of gallons of new whiskey were also consumed in the blaze - however, the distillery is said to have been saved from further physical and financial ruin through the quick reaction of townsfolk who broke down the doors of the warehouses, and helped roll thousands of casks of ageing spirit down the street to safety. In 1887, the distillery was visited by Alfred Barnard, a British writer, as research for his book, "the Whiskey Distilleries of the United Kingdom". By then, the much enlarged distillery was being managed by John's sons, John Edward and James Harvey, who told Barnard that the distillery's output had more than doubled during the preceding ten years, and that they intended to install electric lighting.Barnard noted that the distillery, which he referred to as the "Brusna Distillery", named for the nearby river, was said to be the oldest in Ireland. According to Barnard, the distillery covered 5 acres, and employed a staff of about 70 men, with the aged and sick pensioned-off or assisted. At the time of his visit, the distillery was producing 157,200 proof gallons per annum, though it had the capacity to produce 200,000. The whiskey, which was sold primarily in Dublin, England, and "the Colonies", was "old pot still", produced using four pot stills (two wash stills: 10,320 / 8,436 gallons; and two spirit stills: 6,170 / 6,080 gallons), which had been installed by Millar and Company, Dublin. Barnard remarked that at the time of his visit over 2,000 casks of spirit were ageing in the distillery's bonded warehouses. In 1893, the distillery ceased to be privately held, and was converted a limited stock company, trading as John Locke & Co., Ltd., with nominal capital of £40,000.

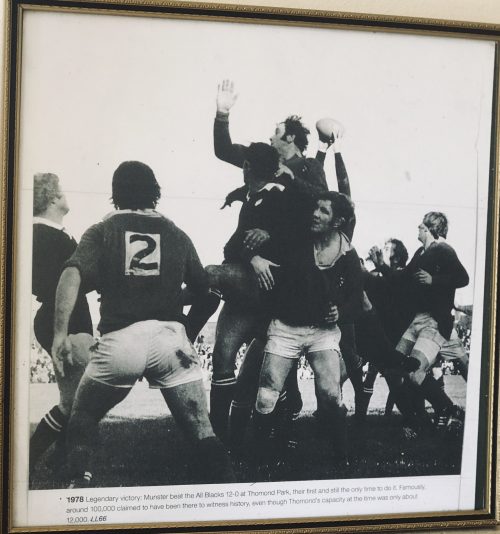

Many years on, Stuart Wilson vividly recalled the Dennison tackles and spoke about them in remarkable detail and with commendable honesty: “The move involved me coming in from the blind side wing and it had been working very well on tour. It was a workable move and it was paying off so we just kept rolling it out. Against Munster, the gap opened up brilliantly as it was supposed to except that there was this little guy called Seamus Dennison sitting there in front of me.

“He just basically smacked the living daylights out of me. I dusted myself off and thought, I don’t want to have to do that again. Ten minutes later, we called the same move again thinking we’d change it slightly but, no, it didn’t work and I got hammered again.”

The game was 11 minutes old when the most famous try in the history of Munster rugby was scored.

Tom Kiernan recalled: “It came from a great piece of anticipation by Bowen who in the first place had to run around his man to get to Ward’s kick ahead. He then beat two men and when finally tackled, managed to keep his balance and deliver the ball to Cantillon who went on to score. All of this was evidence of sharpness on Bowen’s part.”

Very soon it would be 9-0. In the first five minutes, a towering garryowen by skipper Canniffe had exposed the vulnerability of the New Zealand rearguard under the high ball. They were to be examined once or twice more but it was from a long range but badly struck penalty attempt by Ward that full-back Brian McKechnie knocked on some 15 yards from his line and close to where Cantillon had touched down a few minutes earlier. You could sense White, Whelan, McLoughlin and co in the front five of the Munster scrum smacking their lips as they settled for the scrum. A quick, straight put-in by Canniffe, a well controlled heel, a smart pass by the scrum-half to Ward and the inevitability of a drop goal. And that’s exactly what happened.

The All Blacks enjoyed the majority of forward possession but the harder they tried, the more they fell into the trap set by the wily Kiernan and so brilliantly carried out by every member of the Munster team.

The tourists might have edged the line-out contest through Andy Haden and Frank Oliver but scrum-half Mark Donaldson endured a miserable afternoon as the Munster forwards poured through and buried him in the Thomond Park turf.

As the minutes passed and the All Blacks became more and more unsure as to what to try next, the Thomond Park hordes chanted “Munster-Munster–Munster” to an ever increasing crescendo until with 12 minutes to go, the noise levels reached deafening proportions.

And then ... a deep, probing kick by Ward put Wilson under further pressure. Eventually, he stumbled over the ball as it crossed the line and nervously conceded a five-metre scrum. The Munster heel was disrupted but the ruck was won, Tucker gained possession and slipped a lovely little pass to Ward whose gifted feet and speed of thought enabled him in a twinkle to drop a goal although surrounded by a swarm of black jerseys. So the game entered its final 10 minutes with the All Blacks needing three scores to win and, of course, that was never going to happen.

Munster knew this, so, too, did the All Blacks. Stu Wilson admitted as much as he explained his part in Wardy’s second drop goal: “Tony Ward banged it down, it bounced a little bit, jigged here, jigged there, and I stumbled, fell over, and all of a sudden the heat was on me. They were good chasers. A kick is a kick — but if you have lots of good chasers on it, they make bad kicks look good. I looked up and realised — I’m not going to run out of here so I just dotted it down. I wasn’t going to run that ball back out at them because five of those mad guys were coming down the track at me and I’m thinking, I’m being hit by these guys all day and I’m looking after my body, thank you. Of course it was a five-yard scrum and Ward banged over another drop goal. That was it, there was the game”.

The final whistle duly sounded with Munster 12 points ahead but the heroes of the hour still had to get off the field and reach the safety of the dressing room. Bodies were embraced, faces were kissed, backs were pummelled, you name it, the gauntlet had to be walked. Even the All Blacks seemed impressed with the sense of joy being released all about them. Andy Haden recalled “the sea of red supporters all over the pitch after the game, you could hardly get off for the wave of celebration that was going on. The whole of Thomond Park glowed in the warmth that someone had put one over on the Blacks.”

Controversially, the All Blacks coach, Jack Gleeson (usually a man capable of accepting the good with the bad and who passed away of cancer within 12 months of the tour), in an unguarded (although possibly misunderstood) moment on the following day, let slip his innermost thoughts on the game.

“We were up against a team of kamikaze tacklers,” he lamented. “We set out on this tour to play 15-man rugby but if teams were to adopt the Munster approach and do all they could to stop the All Blacks from playing an attacking game, then the tour and the game would suffer.”

It was interpreted by the majority of observers as a rare piece of sour grapes from a group who had accepted the defeat in good spirit and it certainly did nothing to diminish Munster respect for the All Blacks and their proud rugby tradition.

Many years on, Stuart Wilson vividly recalled the Dennison tackles and spoke about them in remarkable detail and with commendable honesty: “The move involved me coming in from the blind side wing and it had been working very well on tour. It was a workable move and it was paying off so we just kept rolling it out. Against Munster, the gap opened up brilliantly as it was supposed to except that there was this little guy called Seamus Dennison sitting there in front of me.

“He just basically smacked the living daylights out of me. I dusted myself off and thought, I don’t want to have to do that again. Ten minutes later, we called the same move again thinking we’d change it slightly but, no, it didn’t work and I got hammered again.”

The game was 11 minutes old when the most famous try in the history of Munster rugby was scored.

Tom Kiernan recalled: “It came from a great piece of anticipation by Bowen who in the first place had to run around his man to get to Ward’s kick ahead. He then beat two men and when finally tackled, managed to keep his balance and deliver the ball to Cantillon who went on to score. All of this was evidence of sharpness on Bowen’s part.”

Very soon it would be 9-0. In the first five minutes, a towering garryowen by skipper Canniffe had exposed the vulnerability of the New Zealand rearguard under the high ball. They were to be examined once or twice more but it was from a long range but badly struck penalty attempt by Ward that full-back Brian McKechnie knocked on some 15 yards from his line and close to where Cantillon had touched down a few minutes earlier. You could sense White, Whelan, McLoughlin and co in the front five of the Munster scrum smacking their lips as they settled for the scrum. A quick, straight put-in by Canniffe, a well controlled heel, a smart pass by the scrum-half to Ward and the inevitability of a drop goal. And that’s exactly what happened.

The All Blacks enjoyed the majority of forward possession but the harder they tried, the more they fell into the trap set by the wily Kiernan and so brilliantly carried out by every member of the Munster team.

The tourists might have edged the line-out contest through Andy Haden and Frank Oliver but scrum-half Mark Donaldson endured a miserable afternoon as the Munster forwards poured through and buried him in the Thomond Park turf.

As the minutes passed and the All Blacks became more and more unsure as to what to try next, the Thomond Park hordes chanted “Munster-Munster–Munster” to an ever increasing crescendo until with 12 minutes to go, the noise levels reached deafening proportions.

And then ... a deep, probing kick by Ward put Wilson under further pressure. Eventually, he stumbled over the ball as it crossed the line and nervously conceded a five-metre scrum. The Munster heel was disrupted but the ruck was won, Tucker gained possession and slipped a lovely little pass to Ward whose gifted feet and speed of thought enabled him in a twinkle to drop a goal although surrounded by a swarm of black jerseys. So the game entered its final 10 minutes with the All Blacks needing three scores to win and, of course, that was never going to happen.

Munster knew this, so, too, did the All Blacks. Stu Wilson admitted as much as he explained his part in Wardy’s second drop goal: “Tony Ward banged it down, it bounced a little bit, jigged here, jigged there, and I stumbled, fell over, and all of a sudden the heat was on me. They were good chasers. A kick is a kick — but if you have lots of good chasers on it, they make bad kicks look good. I looked up and realised — I’m not going to run out of here so I just dotted it down. I wasn’t going to run that ball back out at them because five of those mad guys were coming down the track at me and I’m thinking, I’m being hit by these guys all day and I’m looking after my body, thank you. Of course it was a five-yard scrum and Ward banged over another drop goal. That was it, there was the game”.

The final whistle duly sounded with Munster 12 points ahead but the heroes of the hour still had to get off the field and reach the safety of the dressing room. Bodies were embraced, faces were kissed, backs were pummelled, you name it, the gauntlet had to be walked. Even the All Blacks seemed impressed with the sense of joy being released all about them. Andy Haden recalled “the sea of red supporters all over the pitch after the game, you could hardly get off for the wave of celebration that was going on. The whole of Thomond Park glowed in the warmth that someone had put one over on the Blacks.”

Controversially, the All Blacks coach, Jack Gleeson (usually a man capable of accepting the good with the bad and who passed away of cancer within 12 months of the tour), in an unguarded (although possibly misunderstood) moment on the following day, let slip his innermost thoughts on the game.

“We were up against a team of kamikaze tacklers,” he lamented. “We set out on this tour to play 15-man rugby but if teams were to adopt the Munster approach and do all they could to stop the All Blacks from playing an attacking game, then the tour and the game would suffer.”

It was interpreted by the majority of observers as a rare piece of sour grapes from a group who had accepted the defeat in good spirit and it certainly did nothing to diminish Munster respect for the All Blacks and their proud rugby tradition.

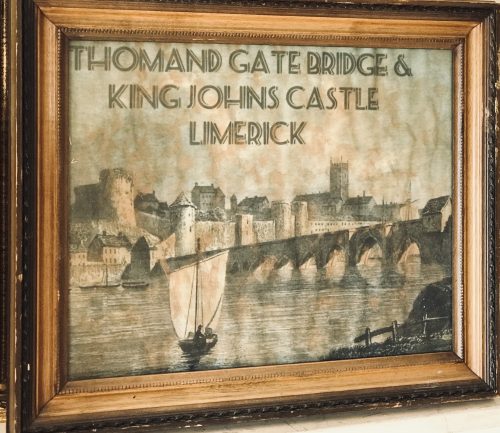

52cm x 60cm Coonagh Co Limerick

52cm x 60cm Coonagh Co Limerick

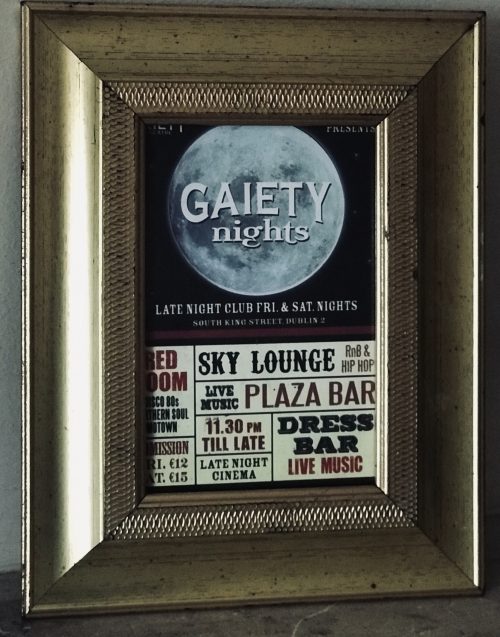

|

|

| Address | South King Street Dublin Ireland |

|---|---|

| Coordinates |  53.340312°N 6.261601°W 53.340312°N 6.261601°W |

| Capacity | 1,145 (on three levels)[1] |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 27 November 1871 |

| Architect | Charles J. Phipps |

| Website | |

| GaietyTheatre.ie | |

| Date | Race name | D(f) | Course | Prize (£) | Odds | Runners | Place | Margin | Runner-up | Time | Jockey |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 October 1885 | Post Sweepstakes | 6 | Newmarket | 500 | 5/4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | Modwena | Fred Archer | |

| 26 October 1885 | Criterion Stakes | 6 | Newmarket | 906 | 4/6 | 6 | 1 | 3 | Oberon | Fred Archer | |

| 28 October 1885 | Dewhurst Stakes | 7 | Newmarket | 1602 | 4/11 | 11 | 1 | 4 | Whitefriar | Fred Archer | |

| 28 April 1886 | 2000 Guineas | 8 | Newmarket | 4000 | 7/2 | 6 | 1 | 2 | Minting | 1:46.8 | George Barrett |

| 26 May 1886 | Epsom Derby | 12 | Epsom Downs | 4700 | 40/85 | 9 | 1 | 1.5 | The Bard | 2:45.6 | Fred Archer |

| 10 June 1886 | St. James's Palace Stakes | 8 | Ascot | 1500 | 3/100 | 3 | 1 | 0.75 | Calais | Fred Archer | |

| 13 June 1886 | Hardwicke Stakes | 12 | Ascot | 2438 | 30/100 | 5 | 1 | 2 | Melton | 2:43 | George Barrett |

| 15 September 1886 | St Leger Stakes | 14.5 | Doncaster | 4475 | 1/7 | 7 | 1 | 4 | St Mirin | 3:21.4 | Fred Archer |

| 29 September 1886 | Great Foal Stakes | 10 | Newmarket | 1140 | 1/25 | 3 | 1 | 3 | Mephisto | Fred Archer | |

| 1 October 1886 | Newmarket St Leger | 16 | Newmarket | 475 | N/A | 1 | 1 | Walkover | Walkover | Fred Archer | |

| 15 October 1886 | Champion Stakes | 10 | Newmarket | 1212 | 1/100 | 3 | 1 | 1 | Oberon | 2:19 | Fred Archer |

| 28 October 1886 | Free Handicap | 10 | Newmarket | 650 | 1/7 | 3 | 1 | 8 | Mephisto | 2:22 | Fred Archer |

| 29 October 1886 | Private Sweepstakes | 10 | Newmarket | 1000 | N/A | 1 | 1 | Walkover | Walkover | Fred Archer | |

| 9 June 1887 | Rous Memorial Stakes | 8 | Ascot | 920 | 1/4 | 1 | 6 | Kilwarlin | Tom Cannon | ||

| 12 June 1887 | Hardwicke Stakes | 12 | Ascot | 2387 | 4/5 | 4 | 1 | 0.25 | Minting | 2:44.4 | Tom Cannon |

| 16 July 1887 | Imperial Gold Cup | 6 | Newmarket | 590 | 30/100 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Whitefriar | 1:18 | Tom Cannon |

| Foaled | Name | Sex | Notable wins | Wins | Prize money |

| 1889 | Goldfinch | c | Biennial Stakes, New Stakes | 2 | £2,464 |

| 1889 | Kilkenny | f | 1 | £164 | |

| 1889 | Llanthony | c | Ascot Derby | 4 | £3,139 |

| 1889 | Orme | c | Middle Park Plate, Dewhurst Plate, Eclipse Stakes (twice), Sussex Stakes, Champion Stakes, Limekiln Stakes, Rous Memorial Stakes, Gordon Stakes | 14 | £32,528 |

| 1889 | Orontes II | f | 0 | ||

| 1889 | Orville | c | 0 | ||

| 1889 | Sorcerer | c | 1 | £229 | |

| 1890 | Glenwood | c | Aylesford Foal Plate | 2 | £1,726 |

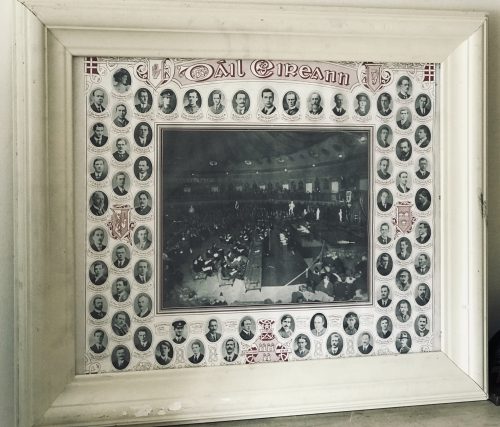

| First Dáil | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Overview | |||||

| Legislative body | Dáil Éireann | ||||

| Jurisdiction | Irish Republic | ||||

| Meeting place | Mansion House, Dublin | ||||

| Term | 21 January 1919 – 10 May 1921 | ||||

| Election | 1918 general election | ||||

| Government | Government of the 1st Dáil | ||||

| Members | 73 | ||||

| Ceann Comhairle | Cathal Brugha (1919) George Noble Plunkett(1919) Seán T. O'Kelly (1919–21) | ||||

| President of Dáil Éireann | Cathal Brugha (1919) | ||||

| President of the Irish Republic | Éamon de Valera (1919–21) | ||||

| Sessions | |||||

|

|||||

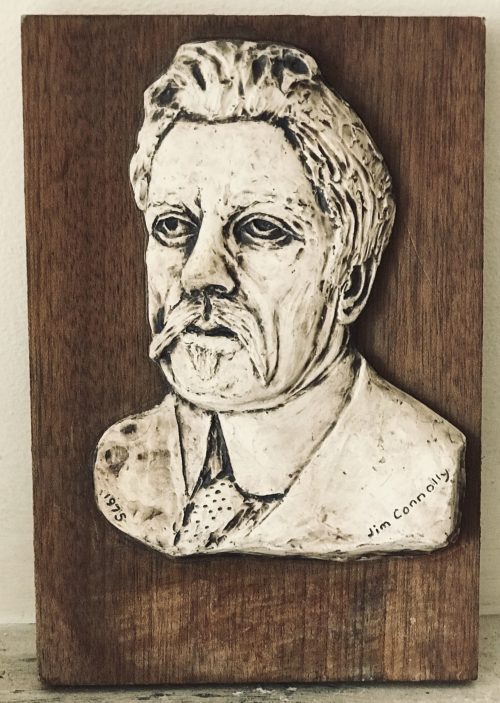

James Connolly was a revolutionary socialist, a trade union leader and a political theorist. His execution by firing squad after the Easter Rising, supported by a chair because of his wounds, significantly contributed to the mood of bitterness in Ireland.

|

This morning a party of one N.C.O. and six men of the Duke of Wellington's Regiment were fired on by a body of civilians outside a bakery in Church Street, Dublin. One soldier was killed and four were wounded. A piquet of the Lancashire Fusiliers in the vicinity, hearing the shots, hurried to their comrades' assistance, and succeeded in arresting one of the aggressors. No arms or equipment were lost by the soldiers.Much was made of Barry's age by Irish newspapers, but the British military pointed out that the three soldiers who had been killed were "much the same age as Barry". On 20 October, Major Reginald Ingram Marians OBE, Head of the Press Section of the General Staff, informed Basil Clarke, Head of Publicity, that Washington was "only 19 and that the other soldiers were of similar ages." General Macready was well aware of the "propaganda value of the soldier's ages." Macready informed General Sir Henry Wilson on the day that sentence was pronounced "of the three men who were killed by him (Barry) and his friends two were 19 and one 20 — official age so probably they were younger... so if you want propaganda there you are."It was later confirmed that Private Harold Washington was 15 years and 351 days old, having been born 4 October 1904. About this competing propaganda, Martin Doherty wrote in a magazine article entitled 'Kevin Barry & the Anglo-Irish Propaganda War':

from the British point of view, therefore, the Anglo-Irish propaganda war was probably unwinable [sic]. Nationalist Ireland had decided that men like Kevin Barry fought to free their country, while British soldiers — young or not — sought to withhold that freedom. In these circumstances, to label Barry a murderer was merely to add insult to injury. The contrasting failure of British propaganda is graphically demonstrated by the simple fact that even in British newspapers Privates Whitehead, Washington and Humphries remained faceless names and numbers, for whom no songs were written.”

He tried to persuade me to give the names, and I persisted in refusing. He then sent the sergeant out of the room for a bayonet. When it was brought in the sergeant was ordered by the same officer to point the bayonet at my stomach ... The sergeant then said that he would run the bayonet into me if I did not tell ... The same officer then said to me that if I persisted in my attitude he would turn me out to the men in the barrack square, and he supposed I knew what that meant with the men in their present temper. I said nothing. He ordered the sergeants to put me face down on the floor and twist my arm ... When I lay on the floor, one of the sergeants knelt on my back, the other two placed one foot each on my back and left shoulder, and the man who knelt on me twisted my right arm, holding it by the wrist with one hand, while he held my hair with the other to pull back my head. The arm was twisted from the elbow joint. This continued, to the best of my judgment, for five minutes. It was very painful ... I still persisted in refusing to answer these questions... A civilian came in and repeated the questions, with the same result. He informed me that if I gave all the information I knew I could get off.On 28 October, the Irish Bulletin (organised by Dick McKee, the IRA Commandant of the Dublin Brigade), a news-sheet produced by Dáil Éireann's Department of Publicity,published Barry's statement alleging torture. The headline read: English Military Government Torture a Prisoner of War and are about to Hang him. The Irish Bulletin declared Barry to be a prisoner of war, suggesting a conflict of principles was at the heart of the conflict. The English did not recognise a war and treated all killings by the IRA as murder. Irish republicans claimed that they were at war and it was being fought between two opposing nations and therefore demanded prisoner of war status. Historian John Ainsworth, author of Kevin Barry, the Incident at Monk's bakery and the Making of an Irish Republican Legend, pointed out that Barry had been captured by the British not as a uniformed soldier but disguised as a civilian and in possession of flat-nosed "Dum-dum" bullets, which expand upon impact, maximising the amount of damage done to the "unfortunate individual" targeted, in contravention of the Hague Convention of 1899. Erskine Childers addressed the question of political status in a letter to the press on 29 October, which was published the day after Barry's execution.

Under similar circumstances a body of Irish Volunteers captured on June 1 of the present year a party of 25 English military who were on duty at the King's Inns, Dublin. Having disarmed the party the Volunteers immediately released their prisoners. This was in strict accordance with the conduct of the Volunteers in all such encounters. Hundreds of members of the armed forces have been from time to time captured by the Volunteers and in no case was any prisoner maltreated even though Volunteers had been killed and wounded in the fighting, as in the case of Cloyne, Co. Cork, when, after a conflict in which one Volunteer was killed and two wounded, the whole of the opposing forces were captured, disarmed, and set at liberty.

He is meeting death as he met life with courage but with nothing of the braggart. He does not believe that he is doing anything wonderfully heroic. Again and again he has begged that no fuss be made about him.He reported Barry as saying "It is nothing, to give one's life for Ireland. I'm not the first and maybe I won't be the last. What's my life compared with the cause?" Barry joked about his death with his sister Kathy. "Well, they are not going to let me like a soldier fall… But I must say they are going to hang me like a gentleman." This was, according to Cronin, a reference to George Bernard Shaw's The Devil's Disciple, the last play Kevin and his sister had seen together. On 31 October, he was allowed three visits of three people each, the last of which was taken by his mother, brother and sisters. In addition to the two Auxiliaries with him, there were five or six warders in the boardroom. As his family were leaving, they met Canon John Waters, on the way in, who said, "This boy does not seem to realise he is going to die in the morning." Mrs Barry asked him what he meant. He said: "He is so gay and light-hearted all the time. If he fully realised it, he would be overwhelmed." Mrs Barry replied, "Canon Waters, I know you are not a Republican. But is it impossible for you to understand that my son is actually proud to die for the Republic?" Canon Waters became somewhat flustered as they parted. The Barry family recorded that they were upset by this encounter because they considered the chief chaplain "the nearest thing to a friend that Kevin would see before his death, and he seemed so alien." Kevin Barry was hanged on 1 November, after hearing two Masses in his cell. Canon Waters, who walked with him to the scaffold, wrote to Barry's mother later, "You are the mother, my dear Mrs Barry, of one of the bravest and best boys I have ever known. His death was one of the most holy, and your dear boy is waiting for you now, beyond the reach of sorrow or trial." Dublin Corporation met on the Monday, and passed a vote of sympathy with the Barry family, and adjourned the meeting as a mark of respect. The Chief Secretary's office in Dublin Castle, on the Monday night, released the following communiqué:

The sentence of death by hanging passed by court-martial upon Kevin Barry, or Berry, medical student, aged 18½ years, for the murder of Private Whitehead in Dublin on September 20, was duly executed this morning at Mountjoy Prison, Dublin. At a military court of inquiry, held subsequently in lieu of an inquest, medical evidence was given to the effect that death was instantaneous. The court found that the sentence had been carried out in accordance with law.Barry's body was buried at 1.30 p.m, in a plot near the women's prison. His comrade and fellow-student Frank Flood was buried alongside him four months later. A plain cross marked their graves and those of Patrick Moran, Thomas Whelan, Thomas Traynor, Patrick Doyle, Thomas Bryan, Bernard Ryan, Edmond Foley and Patrick Maher who were hanged in the same prison before the Anglo-Irish Treaty of July 1921 which ended hostilities between Irish republicans and the British.The men had been buried in unconsecrated ground on the jail property and their graves went unidentified until 1934.They became known as The Forgotten Ten by republicans campaigning for the bodies to be reburied with honour and proper rites.On 14 October 2001, the remains of these ten men were given a state funeral and moved from Mountjoy Prison to be re-interred at Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin.

Many years on, Stuart Wilson vividly recalled the Dennison tackles and spoke about them in remarkable detail and with commendable honesty: “The move involved me coming in from the blind side wing and it had been working very well on tour. It was a workable move and it was paying off so we just kept rolling it out. Against Munster, the gap opened up brilliantly as it was supposed to except that there was this little guy called Seamus Dennison sitting there in front of me.

“He just basically smacked the living daylights out of me. I dusted myself off and thought, I don’t want to have to do that again. Ten minutes later, we called the same move again thinking we’d change it slightly but, no, it didn’t work and I got hammered again.”

The game was 11 minutes old when the most famous try in the history of Munster rugby was scored.

Tom Kiernan recalled: “It came from a great piece of anticipation by Bowen who in the first place had to run around his man to get to Ward’s kick ahead. He then beat two men and when finally tackled, managed to keep his balance and deliver the ball to Cantillon who went on to score. All of this was evidence of sharpness on Bowen’s part.”

Very soon it would be 9-0. In the first five minutes, a towering garryowen by skipper Canniffe had exposed the vulnerability of the New Zealand rearguard under the high ball. They were to be examined once or twice more but it was from a long range but badly struck penalty attempt by Ward that full-back Brian McKechnie knocked on some 15 yards from his line and close to where Cantillon had touched down a few minutes earlier. You could sense White, Whelan, McLoughlin and co in the front five of the Munster scrum smacking their lips as they settled for the scrum. A quick, straight put-in by Canniffe, a well controlled heel, a smart pass by the scrum-half to Ward and the inevitability of a drop goal. And that’s exactly what happened.

The All Blacks enjoyed the majority of forward possession but the harder they tried, the more they fell into the trap set by the wily Kiernan and so brilliantly carried out by every member of the Munster team.

The tourists might have edged the line-out contest through Andy Haden and Frank Oliver but scrum-half Mark Donaldson endured a miserable afternoon as the Munster forwards poured through and buried him in the Thomond Park turf.

As the minutes passed and the All Blacks became more and more unsure as to what to try next, the Thomond Park hordes chanted “Munster-Munster–Munster” to an ever increasing crescendo until with 12 minutes to go, the noise levels reached deafening proportions.

And then ... a deep, probing kick by Ward put Wilson under further pressure. Eventually, he stumbled over the ball as it crossed the line and nervously conceded a five-metre scrum. The Munster heel was disrupted but the ruck was won, Tucker gained possession and slipped a lovely little pass to Ward whose gifted feet and speed of thought enabled him in a twinkle to drop a goal although surrounded by a swarm of black jerseys. So the game entered its final 10 minutes with the All Blacks needing three scores to win and, of course, that was never going to happen.

Munster knew this, so, too, did the All Blacks. Stu Wilson admitted as much as he explained his part in Wardy’s second drop goal: “Tony Ward banged it down, it bounced a little bit, jigged here, jigged there, and I stumbled, fell over, and all of a sudden the heat was on me. They were good chasers. A kick is a kick — but if you have lots of good chasers on it, they make bad kicks look good. I looked up and realised — I’m not going to run out of here so I just dotted it down. I wasn’t going to run that ball back out at them because five of those mad guys were coming down the track at me and I’m thinking, I’m being hit by these guys all day and I’m looking after my body, thank you. Of course it was a five-yard scrum and Ward banged over another drop goal. That was it, there was the game”.

The final whistle duly sounded with Munster 12 points ahead but the heroes of the hour still had to get off the field and reach the safety of the dressing room. Bodies were embraced, faces were kissed, backs were pummelled, you name it, the gauntlet had to be walked. Even the All Blacks seemed impressed with the sense of joy being released all about them. Andy Haden recalled “the sea of red supporters all over the pitch after the game, you could hardly get off for the wave of celebration that was going on. The whole of Thomond Park glowed in the warmth that someone had put one over on the Blacks.”

Controversially, the All Blacks coach, Jack Gleeson (usually a man capable of accepting the good with the bad and who passed away of cancer within 12 months of the tour), in an unguarded (although possibly misunderstood) moment on the following day, let slip his innermost thoughts on the game.

“We were up against a team of kamikaze tacklers,” he lamented. “We set out on this tour to play 15-man rugby but if teams were to adopt the Munster approach and do all they could to stop the All Blacks from playing an attacking game, then the tour and the game would suffer.”

It was interpreted by the majority of observers as a rare piece of sour grapes from a group who had accepted the defeat in good spirit and it certainly did nothing to diminish Munster respect for the All Blacks and their proud rugby tradition.

Many years on, Stuart Wilson vividly recalled the Dennison tackles and spoke about them in remarkable detail and with commendable honesty: “The move involved me coming in from the blind side wing and it had been working very well on tour. It was a workable move and it was paying off so we just kept rolling it out. Against Munster, the gap opened up brilliantly as it was supposed to except that there was this little guy called Seamus Dennison sitting there in front of me.

“He just basically smacked the living daylights out of me. I dusted myself off and thought, I don’t want to have to do that again. Ten minutes later, we called the same move again thinking we’d change it slightly but, no, it didn’t work and I got hammered again.”

The game was 11 minutes old when the most famous try in the history of Munster rugby was scored.

Tom Kiernan recalled: “It came from a great piece of anticipation by Bowen who in the first place had to run around his man to get to Ward’s kick ahead. He then beat two men and when finally tackled, managed to keep his balance and deliver the ball to Cantillon who went on to score. All of this was evidence of sharpness on Bowen’s part.”

Very soon it would be 9-0. In the first five minutes, a towering garryowen by skipper Canniffe had exposed the vulnerability of the New Zealand rearguard under the high ball. They were to be examined once or twice more but it was from a long range but badly struck penalty attempt by Ward that full-back Brian McKechnie knocked on some 15 yards from his line and close to where Cantillon had touched down a few minutes earlier. You could sense White, Whelan, McLoughlin and co in the front five of the Munster scrum smacking their lips as they settled for the scrum. A quick, straight put-in by Canniffe, a well controlled heel, a smart pass by the scrum-half to Ward and the inevitability of a drop goal. And that’s exactly what happened.

The All Blacks enjoyed the majority of forward possession but the harder they tried, the more they fell into the trap set by the wily Kiernan and so brilliantly carried out by every member of the Munster team.

The tourists might have edged the line-out contest through Andy Haden and Frank Oliver but scrum-half Mark Donaldson endured a miserable afternoon as the Munster forwards poured through and buried him in the Thomond Park turf.

As the minutes passed and the All Blacks became more and more unsure as to what to try next, the Thomond Park hordes chanted “Munster-Munster–Munster” to an ever increasing crescendo until with 12 minutes to go, the noise levels reached deafening proportions.

And then ... a deep, probing kick by Ward put Wilson under further pressure. Eventually, he stumbled over the ball as it crossed the line and nervously conceded a five-metre scrum. The Munster heel was disrupted but the ruck was won, Tucker gained possession and slipped a lovely little pass to Ward whose gifted feet and speed of thought enabled him in a twinkle to drop a goal although surrounded by a swarm of black jerseys. So the game entered its final 10 minutes with the All Blacks needing three scores to win and, of course, that was never going to happen.

Munster knew this, so, too, did the All Blacks. Stu Wilson admitted as much as he explained his part in Wardy’s second drop goal: “Tony Ward banged it down, it bounced a little bit, jigged here, jigged there, and I stumbled, fell over, and all of a sudden the heat was on me. They were good chasers. A kick is a kick — but if you have lots of good chasers on it, they make bad kicks look good. I looked up and realised — I’m not going to run out of here so I just dotted it down. I wasn’t going to run that ball back out at them because five of those mad guys were coming down the track at me and I’m thinking, I’m being hit by these guys all day and I’m looking after my body, thank you. Of course it was a five-yard scrum and Ward banged over another drop goal. That was it, there was the game”.

The final whistle duly sounded with Munster 12 points ahead but the heroes of the hour still had to get off the field and reach the safety of the dressing room. Bodies were embraced, faces were kissed, backs were pummelled, you name it, the gauntlet had to be walked. Even the All Blacks seemed impressed with the sense of joy being released all about them. Andy Haden recalled “the sea of red supporters all over the pitch after the game, you could hardly get off for the wave of celebration that was going on. The whole of Thomond Park glowed in the warmth that someone had put one over on the Blacks.”

Controversially, the All Blacks coach, Jack Gleeson (usually a man capable of accepting the good with the bad and who passed away of cancer within 12 months of the tour), in an unguarded (although possibly misunderstood) moment on the following day, let slip his innermost thoughts on the game.

“We were up against a team of kamikaze tacklers,” he lamented. “We set out on this tour to play 15-man rugby but if teams were to adopt the Munster approach and do all they could to stop the All Blacks from playing an attacking game, then the tour and the game would suffer.”

It was interpreted by the majority of observers as a rare piece of sour grapes from a group who had accepted the defeat in good spirit and it certainly did nothing to diminish Munster respect for the All Blacks and their proud rugby tradition.

| Desert Orchid | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Sire | Grey Mirage |

| Grandsire | Double-U-Jay |

| Dam | Flower Child |

| Damsire | Brother |

| Sex | Gelding |

| Foaled | 11 April 1979 in Goadby, Leicestershire, England. |

| Country | Great Britain |

| Colour | Grey |

| Breeder | James Burridge |

| Owner | James Burridge, Midge Burridge, Richard Burridge, Simon Bullimore |

| Trainer | David Elsworth at Whitsbury Manor Racing Stables, Fordingbridge, Wiltshire |

| Record | 70: 34-11-8 |

| Earnings | £654,066 |

| Major wins | |

| Tolworth Hurdle (1984) Kingwell Hurdle (1984) Hurst Park Novices' Chase (1985) King George VI Chase (1986, 1988, 1989, 1990) Gainsborough Chase (1987, 1989, 1991) Martell Cup (1988) Whitbread Gold Cup (1988) Tingle Creek Chase (1988) Victor Chandler Chase (1989) Cheltenham Gold Cup (1989) Racing Post Chase (1990) Irish Grand National (1990) | |

| Awards | |

| Timeform rating: 187 | |

| Honours | |

| The Desert Orchid Chase at Wincanton Desert Orchid Chase at Kempton Park Racecourse Statue, ashes, headstone - Kempton Park Racecourse | |

| Cork Jazz Festival | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Genre | Jazz |

| Dates | Late October |

| Location(s) | Cork, Ireland |

| Years active | 1978-present (42 years) |

| Website | GuinnessJazzFestival.com |