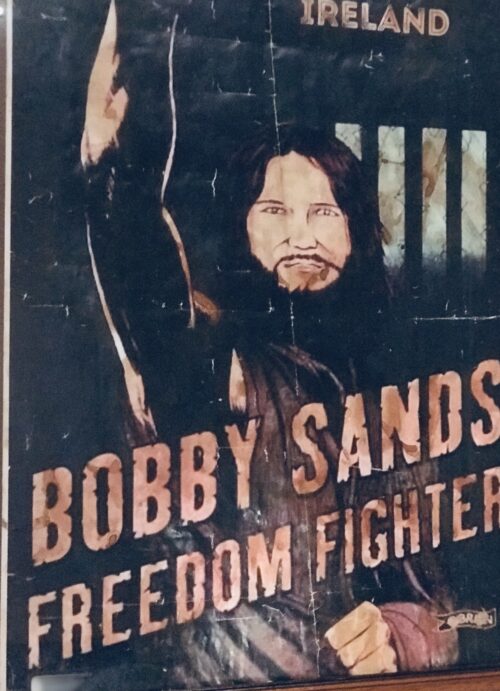

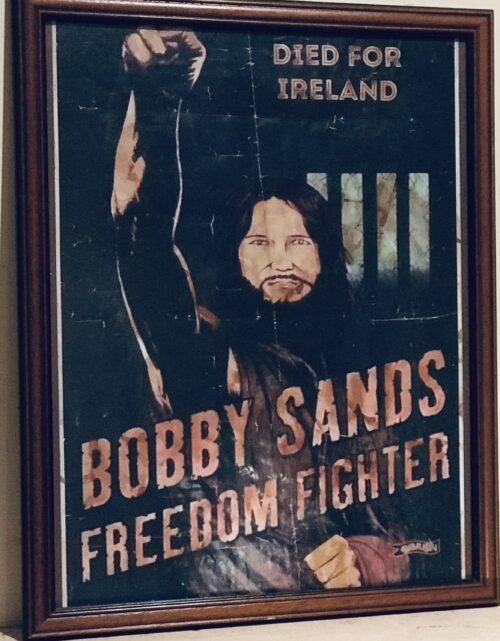

Very unusual framed Che Guevera style iconic image of Bobby Sands.

48cm x 38cm Belfast

Bobby Sands or Riobard Gearóid Ó Seachnasaigh;

9 March 1954 – 5 May 1981) was a member of the

Provisional Irish Republican Army who died on

hunger strike while imprisoned at

HM Prison Maze in

Northern Ireland after being sentenced for firearms possession.

He was the leader of the

1981 hunger strike in which

Irish republican prisoners protested against the removal of

Special Category Status. During Sands's strike, he was elected to the

British Parliament as an

Anti H-Block candidate.

His death and those of nine other hunger strikers was followed by a new surge of Provisional IRA recruitment and activity. International media coverage brought attention to the hunger strikers, and the Republican movement in general, attracting both praise and criticism.

Sands was born in 1954 to John and Rosaleen Sands.

After marrying, they relocated to the new development of Abbots Cross,

Newtownabbey,

County Antrim, outside North

Belfast.

Sands was the eldest of four children. His younger sisters, Marcella and

Bernadette, were born in 1955 and 1958, respectively. He also had a younger brother, John, born 1962.

After experiencing harassment and intimidation from their neighbours, the family abandoned the development and moved in with friends for six months before being granted housing in the nearby

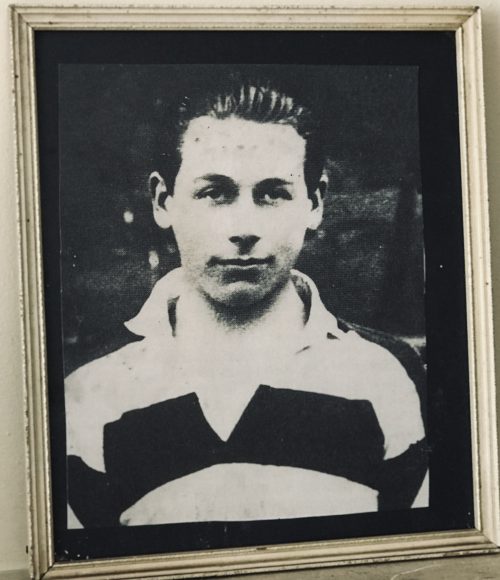

Rathcoole development. Rathcoole was 30% Catholic and featured Catholic schools as well as a nominally Catholic but religiously mixed, youth

football club, an unusual circumstance in Northern Ireland, known as Stella Maris, the same as the school Sands attended and where the training was held. Sands was a member of this club and played

left-back.

There was another youth club in nearby Greencastle called Star of the Sea and many boys went there when the Stella Maris club closed.

By 1966, sectarian violence in Rathcoole, along with the rest of Belfast, had considerably worsened, and the minority Catholic population there found itself under siege. Despite always having had Protestant friends, Sands suddenly found that none of them would even speak to him, and he quickly learned to associate only with Catholics.

He left school in 1969 at age 15, and enrolled in Newtownabbey Technical College, beginning an apprenticeship as a

coach builder at Alexander's Coach Works in 1970. He worked there for less than a year, enduring constant harassment from his Protestant co-workers, which according to several co-workers he ignored completely, as he wished to learn a meaningful trade.

He was eventually confronted after leaving his shift in January 1971 by a number of his coworkers wearing the armbands of the local

Ulster loyalist tartan gang. He was held at gunpoint and told that Alexander's was off-limits to "

Fenian scum" and to never come back if he valued his life. He later said that this event was the point at which he decided that militancy was the only solution.

In June 1972, Sands's parents' home was attacked and damaged by a loyalist mob and they were again forced to move, this time to the West Belfast Catholic area of

Twinbrook, where Sands, now thoroughly embittered, rejoined them. He attended his first

Provisional IRA meeting in Twinbrook that month and joined the IRA the same day. He was 18 years old. By 1973, almost every Catholic family had been driven out of Rathcoole by violence and intimidation, although there were some who remained.

In 1972, Sands joined the Provisional IRA.

He was arrested and charged in October 1972 with possession of four handguns found in the house where he was staying. Sands was convicted in April 1973, sentenced to five years imprisonment, and released in April 1976.

Upon his release, he returned to his family home in West Belfast, and resumed his active role in the Provisional IRA. Sands and

Joe McDonnell planned the October 1976 bombing of the Balmoral Furniture Company in

Dunmurry. The showroom was destroyed but as the IRA men left the scene there was a gun battle with the

Royal Ulster Constabulary. Leaving behind two wounded, Seamus Martin and Gabriel Corbett, the remaining four (Sands, McDonnell, Seamus Finucane, and Sean Lavery) tried to escape by car, but were arrested. One of the revolvers used in the attack was found in the car. In 1977, the four men were sentenced to 14 years for possession of the revolver. They were not charged with explosive offences.

Immediately after his sentencing, Sands was implicated in a fight and spent the first 22 days with all furniture removed from his cell in

Crumlin Road Prison, 15 days naked, and a diet of bread and water every three days.

In late 1980, Sands was chosen

Officer Commanding of the Provisional IRA prisoners in the

Maze Prison, succeeding

Brendan Hughes who was participating in the

first hunger strike. Republican prisoners organised a series of protests seeking to regain their previous

Special Category Status, which would free them from some ordinary prison regulations. This began with the "

blanket protest" in 1976, in which the prisoners refused to wear prison uniforms and wore blankets instead. In 1978, after a number of attacks on prisoners leaving their cells to "

slop out" (i.e., empty their chamber pots), this escalated into the "

dirty protest", wherein prisoners refused to wash and smeared the walls of their cells with excrement.

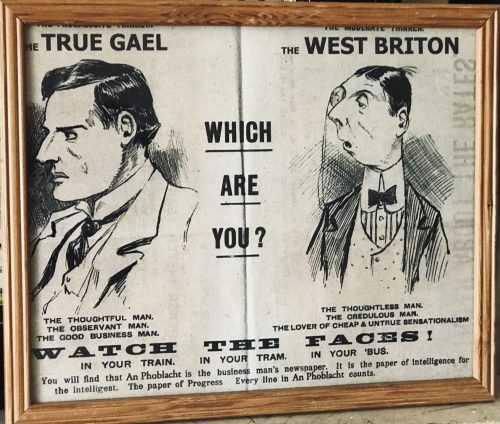

While in prison, Sands had several letters and articles published in the Republican paper

An Phoblacht under the pseudonym "Marcella" (his sister's name). Other writings attributed to him are:

Skylark Sing Your Lonely Song and

One Day in My Life.

Sands also wrote the lyrics of "

Back Home in Derry" and "McIlhatton", which were both later recorded by

Christy Moore, and "Sad Song For Susan", which was also later recorded. The melody of "Back Home in Derry" was borrowed from

Gordon Lightfoot's 1976 song "

The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald".

The song itself is about the

penal transportation of Irishmen in the 19th century to

Van Diemen's Land (modern day

Tasmania,

Australia).

Shortly after the beginning of the strike,

Frank Maguire, the

Independent Republican MP for

Fermanagh and South Tyrone, died suddenly of a heart attack, precipitating the

April 1981 by-election.

The sudden vacancy in a seat with a nationalist majority of about 5,000 was a valuable opportunity for Sands's supporters "to raise public consciousness".

Pressure not to split the vote led other nationalist parties, notably the

Social Democratic and Labour Party, to withdraw, and Sands was nominated on the label "

Anti H-Block/Armagh Political Prisoner". After a highly polarised campaign, Sands narrowly won the seat on 9 April 1981, with 30,493 votes to 29,046 for the

Ulster Unionist Party candidate

Harry West. Sands became the youngest MP at the time.

Sands died in prison less than a month later, without ever having taken his seat in the Commons.

Following Sands's election win, the British government introduced the

Representation of the People Act 1981 which prevents prisoners serving jail terms of more than one year in either the UK or the

Republic of Ireland from being nominated as candidates in British elections.

The enactment of the law, as a response to the election of Sands, consequently prevented other hunger strikers from being elected to the House of Commons.

The

1981 Irish hunger strike started with Sands refusing food on 1 March 1981. Sands decided that other prisoners should join the strike at staggered intervals to maximise publicity, with prisoners steadily deteriorating successively over several months. The hunger strike centred on five demands:

- the right not to wear a prison uniform;

- the right not to do prison work;

- the right of free association with other prisoners, and to organise educational and recreational pursuits;

- the right to one visit, one letter, and one parcel per week;

- full restoration of remission lost through the protest.

The significance of the hunger strike was the prisoners' aim of being considered

political prisoners as opposed to criminals. Shortly before Sands's death,

The Washington Post reported that the primary aim of the hunger strike was to generate international publicity.

Sands died on 5 May 1981 in the Maze's prison hospital after 66 days on hunger strike, aged 27.

The original

pathologist's report recorded the hunger strikers' causes of death as "self-imposed starvation", later amended to simply "starvation" after protests from the dead strikers' families.

The

coronerrecorded verdicts of "starvation, self-imposed".

Sands became a

martyr to Irish republicans,

and the announcement his death prompted several days of rioting in

nationalist areas of

Northern Ireland. A milkman, Eric Guiney, and his son, Desmond, died as a result of injuries sustained when their

milk float crashed after being stoned by rioters in a predominantly nationalist area of North Belfast.

Over 100,000 people lined the route of Sands's funeral, and he was buried in the

'New Republican Plot' alongside 76 others. Their graves are maintained by the

National Graves Association, Belfast.

Britain

In response to a question in the

House of Commons on 5 May 1981, the United Kingdom Prime Minister,

Margaret Thatcher said, "Mr Sands was a convicted criminal. He chose to take his own life. It was a choice that his organisation did not allow to many of its victims".

Cardinal Basil Hume, head of the

Catholic Church in England and Wales, condemned Sands, describing the hunger strike as a form of violence. However, he noted that this was his personal view. The Roman Catholic Church's official stance was that ministrations should be provided to the hunger strikers who, believing their sacrifice to be for a higher good, were acting in good conscience.

At

Old Firm football matches in

Glasgow, Scotland, some

Rangers fans have been known to sing songs mocking Sands to taunt fans of

Celtic. Rangers fans are mainly

Protestant, and predominantly sympathetic to unionists; Celtic fans are traditionally more likely to support nationalists.

Celtic fans regularly sing the republican song

The Roll of Honour, which commemorates the ten men who died in the 1981 hunger strike, amongst other songs in support of the IRA. Sands is honoured in the line "They stood beside their leader – the gallant Bobby Sands." Rangers' taunts have since been adopted by the travelling support of other UK clubs, particularly those with strong

British nationalist ties, as a form of

anti-Irish sentiment.

The

1981 British Home Championship football tournament was cancelled following the refusal of teams from England and Wales to travel to Northern Ireland in the aftermath of his death, due to security concerns.

Europe

A memorial mural to Sands along Falls Road, Belfast

In Europe, there were widespread protests after Sands's death. 5,000

Milanese students burned the

Union Flag and chanted "Freedom for Ulster" during a march.

The British Consulate at

Ghent was raided.

Thousands marched in Paris behind huge portraits of Sands, to chants of "the IRA will conquer".

In the

Portuguese Parliament, the

opposition stood for Sands.

In

Oslo, demonstrators threw a tomato at

Elizabeth II, the

Queen of the United Kingdom, but missed. (One 28-year-old assailant said he had actually aimed for what he claimed was a smirking British soldier.)

In the

Soviet Union,

Pravdadescribed it as "another tragic page in the grim chronicle of oppression, discrimination, terror, and violence" in Ireland. Russian fans of Bobby Sands published a translation of the "Back Home in Derry" song ("На Родину в Дерри" in Russian).

Many French towns and cities have streets named after Sands, including

Nantes,

Saint-Étienne,

Le Mans,

Vierzon, and

Saint-Denis.

The conservative-aligned West German newspaper

Die Welt took a negative view towards Sands.

Americas

A number of political, religious, union and fund-raising institutions chose to honour Sands in the United States. The

International Longshoremen's Association in New York announced a 24-hour boycott of British ships.

Over 1,000 people gathered in

New York's St. Patrick's Cathedral to hear

Cardinal Terence Cooke offer a reconciliation

Mass for Northern Ireland. Irish bars in the city were closed for two hours in mourning.

The

New Jersey General Assembly, the

lower house of the

New Jersey Legislature, voted 34–29 for a resolution honouring his "courage and commitment."

The American media expressed a range of opinions on Sands's death.

The Boston Globe commented, a few days before Sands's death, that "[t]he slow suicide attempt of Bobby Sands has cast his land and his cause into another downward spiral of death and despair. There are no heroes in the saga of Bobby Sands".

The

Chicago Tribune wrote that "

Mahatma Gandhi used the hunger strike to move his countrymen to abstain from fratricide. Bobby Sands's deliberate slow suicide is intended to precipitate civil war. The former deserved veneration and influence. The latter would be viewed, in a reasonable world, not as a charismatic martyr but as a fanatical suicide, whose regrettable death provides no sufficient occasion for killing others".

The New York Times wrote that "Britain's prime minister Thatcher is right in refusing to yield political status to Bobby Sands, the Irish Republican Army hunger striker", but added that by appearing "unfeeling and unresponsive" the British Government was giving Sands "the crown of martyrdom".

The

San Francisco Chronicle argued that political belief should not exempt activists from criminal law:

Terrorism goes far beyond the expression of political belief. And dealing with it does not allow for compromise as many countries of Western Europe and United States have learned. The bombing of bars, hotels, restaurants, robbing of banks, abductions, and killings of prominent figures are all criminal acts and must be dealt with by criminal law.

Some American critics and journalists suggested that American press coverage was a "melodrama".

Edward Langley of The Pittsburgh Press criticised the large pro-IRA Irish-American contingent which "swallow IRA propaganda as if it were

taffy", and concluded that IRA "terrorist propaganda triumphs."

Archbishop John R. Roach, president of the US Catholic bishops, called Sands's death "a useless sacrifice".

The Ledger of 5 May 1981 under the headline "To some he was a hero, to others a terrorist" claims that the hunger strike made Sands "a hero among Irish Republicans or Nationalists seeking the reunion of Protestant-dominated and British-ruled Northern Ireland with the predominantly Catholic Irish Republic to the south".

The Ledger cited Sands as telling his friends: "If I die, God will understand" and one of his last messages was "Tell everyone I'll see them somewhere, sometime".

In

Hartford, Connecticut, a memorial was dedicated to Bobby Sands and the other hunger strikers in 1997, the only one of its kind in the United States. Set up by the

Irish Northern Aid Committeeand local Irish-Americans, it stands in a traffic island known as Bobby Sands Circle at the bottom of Maple Avenue near Goodwin Park.

In 2001, a memorial to Sands and the other hunger strikers was unveiled in

Havana, Cuba.

Asia

The Iranian government renamed Winston Churchill Boulevard, the location of the

Embassy of the United Kingdom in Tehran, to Bobby Sands Street, prompting the embassy to move its entrance door to Ferdowsi Avenue to avoid using Bobby Sands Street on its letterhead.

A street in the

Elahieh district is also named after Sands.

An official blue and white street sign was affixed to the rear wall of the British embassy compound saying (in Persian)

"Bobby Sands Street" with three words of explanation

"militant Irish guerrilla".

The official

Pars News Agency called Bobby Sands's death "heroic".

There have been claims that the British pressured Iranian authorities to change the name of

Bobby Sands Street but this was denied.

A burger bar in Tehran is named in honour of Sands.

- Palestinian prisoners incarcerated in the Israeli desert prison of Nafha sent a letter, which was smuggled out and reached Belfast in July 1981, which read: "To the families of Bobby Sands and his martyred comrades. We, revolutionaries of the Palestinian people...extend our salutes and solidarity with you in the confrontation against the oppressive terrorist rule enforced upon the Irish people by the British ruling elite. We salute the heroic struggle of Bobby Sands and his comrades, for they have sacrificed the most valuable possession of any human being. They gave their lives for freedom."

- The Hindustan Times said Margaret Thatcher had allowed a fellow Member of Parliament to die of starvation, an incident which had never before occurred "in a civilised country".

- In the Indian Parliament, opposition members in the upper house Rajya Sabha stood for a minute's silence in tribute. The ruling Congress Party did not participate. Protest marches were organised against the British government and in tribute to Sands and his fellow hunger strikers.

- The Hong Kong Standard said it was "sad that successive British governments have failed to end the last of Europe's religious wars".

Nine other IRA and

Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) members who were involved in the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike died after Sands. On the day of Sands's funeral, Unionist leader

Ian Paisleyheld a memorial service outside of Belfast city hall to commemorate the victims of the IRA.

In the Irish general elections held the same year, two anti H-block candidates won seats on an abstentionist basis.

The media coverage that surrounded the death of Sands resulted in a new surge of IRA activity and an immediate escalation in

the Troubles, with the group obtaining many more members and increasing its fund-raising capability. Both nationalists and unionists began to harden their attitudes and move towards political extremes.

Sands's Westminster seat was taken by his election agent,

Owen Carron standing as 'Anti H-Block Proxy Political Prisoner' with an increased majority.

The

Éire Nua flute band inspired by Bobby Sands, commemorate the 1916

Easter Rising on the 91st anniversary.

The Grateful Dead played the

Nassau Coliseum the following night after Sands died and guitarist

Bob Weir dedicated the song "He's Gone" to Sands.

The concert was later released as

Dick's Picks Volume 13, part of the Grateful Dead's programme of live concert releases.

Songs written in response to the hunger strikes and Sands's death include songs by

Black 47,

Nicky Wire,

Meic Stevens,

The Undertones,

Eric Bogle,

Soldat Louis and

Christy Moore. Moore's song, "

The People's Own MP", has been described as an example of a

rebel song of the "hero-martyr" genre in which Sands's "intellectual, artistic and moral qualities" are

eulogised.

The U.S. rock band

Rage Against the Machine listed Sands as an inspiration in the sleeve notes of their

self-titled debut album and as a "political hero" in media interviews.

Celtic F.C., a Scottish football club, received a €50,000 fine from

UEFA over banners depicting Sands with a political message, which were displayed during a game on 26 November 2013

by

Green Brigade fans.

Bobby Sands has been portrayed in the following films:

Sands married Geraldine Noade while in prison on robbery charges on 3

March

1973. His son, Gerard, was born 8 May 1973. Noade soon left to live in England with their son.

Sands's sister,

Bernadette Sands McKevitt, is also a prominent

Irish Republican. Along with her husband,

Michael McKevitt, she helped to form the

32 County Sovereignty Movement and is accused of involvement with the

Real Irish Republican Army (RIRA).

Bernadette Sands McKevitt is opposed to the

Belfast Agreement, stating that "Bobby did not die for cross-border bodies with executive powers. He did not die for nationalists to be equal British citizens within the Northern Ireland state."

The RIRA was responsible for the

Omagh bombing on 15 August 1998, in which 29 people, including a mother pregnant with twins, were killed and more than 200 injured. This is the highest death toll from a single incident during

the Troubles. Michael McKevitt was one of those named in a civil suit filed by victims and survivors.

Origins:Co Antrim